kidneys – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

Healing Switch Links Acute Kidney Injury to Fibrosis, Suggesting Way to Protect Kidney Function

Posted on March 7th, 2024 by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

The protein Sox9 switches on after kidney injury, then back off after repair. When healing doesn’t proceed optimally, Sox9 stays on, leading to scarring and fibrosis. Credit: Donny Bliss/NIH

Healthy kidneys—part of the urinary tract—remove waste and help balance chemicals and fluids in the body. However, our kidneys have a limited ability to regenerate healthy tissue after sustaining injuries from conditions such as diabetes or high blood pressure. Injured kidneys are often left with a mix of healthy and scarred tissue, or fibrosis, which over time can compromise their function and lead to chronic kidney disease or complete kidney failure. More than one in seven adults in the U.S. are estimated to have chronic kidney disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, most without knowing it.

Now, a team of researchers led by Sanjeev Kumar at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, has identified a key molecular “switch” that determines whether injured kidney tissue will heal or develop those damaging scars.1 Their findings, reported in the journal Science, could lead to new and less invasive ways to detect fibrosis in the kidneys. The research could also point toward a targeted therapeutic approach that might prevent or reverse scarring to protect kidney function.

In earlier studies, the research team found that a protein called Sox9 plays an important role in switching on the repair response in kidneys after acute injury.2 In some cases, the researchers noticed that Sox9 remained active for a prolonged period of a month or more. They suspected this might be a sign of unresolved injury and repair.

By conducting studies using animal models of kidney damage, the researchers found that cells that turned Sox9 on and then back off healed without fibrosis. However, cells that failed to regenerate healthy kidney cells kept Sox9 on indefinitely, which in turn led to the production of fibrosis and scarring.

According to Kumar, Sox9 appears to act like a sensor, switching on after injury. Once restored to health, Sox9 switches back off. When healing doesn’t proceed optimally, Sox9 stays on, leading to scarring. Importantly, the researchers also found they could encourage kidneys to recover by forcing Sox9 to turn off a week after an injury, suggesting it may be a promising drug target.

The researchers also looked for evidence of this process in human patients who have received kidney transplants. They could see that, when transplanted kidneys took longer to start working, Sox9 was switched on. Those whose kidneys continued to produce Sox9 also had lower kidney function and more scarring compared to those who didn’t.

The findings suggest that the dynamics observed in animal studies may be clinically relevant in people, and that treatments targeting Sox9 might promote kidneys to heal instead of scarring. The researchers say they hope that similar studies in the future will lead to greater understanding of healing and fibrosis in other organs—including the heart, lungs, and liver—with potentially important clinical implications.

References:

[1] Aggarwal S, et al. SOX9 switch links regeneration to fibrosis at the single-cell level in mammalian kidneys. Science. DOI: 10.1126/science.add6371 (2024).

[2] Kumar S, et al. Sox9 Activation Highlights a Cellular Pathway of Renal Repair in the Acutely Injured Mammalian Kidney. Cell Reports. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.034 (2015).

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Chipping Away at the Causes of Polycystic Kidney Disease

Posted on January 17th, 2023 by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

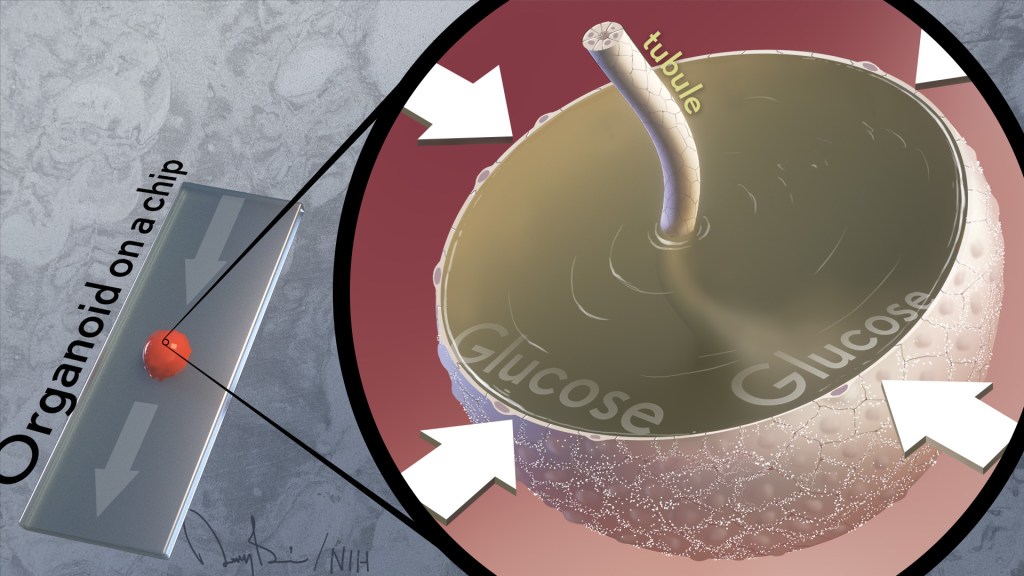

Caption: Image depicts formation of cyst (surrounded by white arrows) within kidney organoid on a chip. As cyst absorbs glucose passing through the tubule, it grows larger.

It’s often said that two is better than one. That’s true whether driving across the country, renovating a kitchen, or looking for a misplaced set of car keys. But a recent study shows this old saying also applies for modeling a kidney disease with two very complementary, cutting-edge technologies: an organoid, a living miniaturized organ grown in a laboratory dish; and an “organ-on-a-chip,” silicon chips specially engineered to mimic the 3D tissue structure and basic biology of a human body organ.

Using this one-two approach at the lab bench, the researchers modeled in just a few weeks different aspects of the fluid-filled cysts that form in polycystic kidney disease (PKD), a common cause of kidney failure. This is impossible to do in real-time in humans for a variety of technical reasons.

These powerful technologies revealed that blood glucose plays a role in causing the cysts. They also showed the cysts form via a different biological mechanism than previously thought. These new leads, if confirmed, offer a whole new way of thinking about PKD cysts, and more exciting, how to prevent or slow the disease in millions of people worldwide.

These latest findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, come from Benjamin Freedman and colleagues at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle [1]. While much is known about the genetic causes of PKD, Freedman and team realized there’s much still much to learn about the basics of how cysts form in the kidney’s tiny tubes, or tubules, that help to filter toxins out of the bloodstream.

Each human kidney has millions of tubules, and in people with PKD, some of them expand gradually and abnormally to form sacs of fluid that researchers liken to water balloons. These sacs, or cysts, crowd out healthy tissue, leading over time to reduced kidney function and, in some instances, complete kidney failure.

To understand cyst formation better, Freedman’s team and others have invented methods to grow human kidney organoids, complete with a system of internal tubules. Impressively, organoids made from cells carrying mutations known to cause PKD develop cysts, just as people with these same mutations do. When suspended in fluid, the organoids also develop telltale signs of PKD even more dramatically, showing they are sensitive to changes in their environments.

At any given moment, about a quarter of all the fluids in the body pass through the kidneys, and this constant flow was missing from the organoid. That’s when Freedman and colleagues turned to their other modeling tool: a kidney-on-a-chip.

These more complex 3D models, containing living kidney cells, aim to mimic more fully the kidney and its environment. They also contain a network of microfluidic channels to replicate the natural flow of fluids in a living kidney. Combining PKD organoids with kidney-on-a-chip technology provided the best of both worlds.

Their studies found that exposing PKD organoid-on-a-chip models to a solution including water, glucose, amino acids, and other nutrients caused cysts to expand more quickly than they otherwise would. However, the cysts don’t develop from fluids that the kidneys outwardly secrete, as long thought. The new findings reveal just the opposite. The PKD cysts arise and grow as the kidney tissue works to retain most of the fluids that constantly pass through them.

They also found out why: the cysts were absorbing glucose and taking in water from the fluid passing over them, causing the cysts to expand. Although scientists had known that kidneys absorb glucose, they’d never connected this process to the formation of cysts in PKD.

In further studies, the scientists gave fluorescently labeled glucose to mice with PKD and could see that kidney cysts in the animals also took up glucose. The researchers think that the tubules are taking in fluid in the mice just as they do in the organoids.

Understanding the mechanisms of PKD can point to new ways to treat it. Indeed, the research team showed adding compounds that block the transport of glucose also prevented cyst growth. Freedman notes that glucose transport inhibitors (flozins), a class of oral drugs now used to treat diabetes, are in development for other types of kidney disease. He said the new findings suggest glucose transport inhibitors might have benefits for treating PKD, too.

There’s much more work to do. But the hope is that these new insights into PKD biology will lead to promising ways to prevent or treat this genetic condition that now threatens the lives of far too many loved ones in so many families.

This two-is-better-than-one approach is just an example of the ways in which NIH-supported efforts in tissue chips are evolving to better model human disease. That includes NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Science’s Tissue Chip for Drug Screening program, which is enabling promising new approaches to study human diseases affecting organ systems throughout the body.

Reference:

[1] Glucose absorption drives cystogenesis in a human organoid-on-chip model of polycystic kidney disease. Li SR, Gulieva RE, Helms L, Cruz NM, Vincent T, Fu H, Himmelfarb J, Freedman BS. Nat Commun. 2022 Dec 23;13(1):7918.

Links:

Polycystic Kidney Disease (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Your Kidneys & How They Work (NIDDK)

Freedman Lab (University of Washington, Seattle)

Tissue Chip for Drug Screening (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

NIH Support: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Posted In: News

Tags: autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, basic science, floxins, glucose, glucose transport inhibitors, kidney, kidney cysts, kidney disease, kidney failure, kidney organoid, kidney tubules, kidneys, NCATS, organ on a chip, organoids, PKD, Tissue Chip for Drug Screening Program

A Race-Free Approach to Diagnosing Chronic Kidney Disease

Posted on October 21st, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: True Touch Lifestyle; crystal light/Shutterstock

Race has a long and tortured history in America. Though great strides have been made through the work of leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to build an equal and just society for all, we still have more work to do, as race continues to factor into American life where it shouldn’t. A medical case in point is a common diagnostic tool for chronic kidney disease (CKD), a condition that affects one in seven American adults and causes a gradual weakening of the kidneys that, for some, will lead to renal failure.

The diagnostic tool is a medical algorithm called estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). It involves getting a blood test that measures how well the kidneys filter out a common waste product from the blood and adding in other personal factors to score how well a person’s kidneys are working. Among those factors is whether a person is Black. However, race is a complicated construct that incorporates components that go well beyond biological and genetic factors to social and cultural issues. The concern is that by lumping together Black people, the algorithm lacks diagnostic precision for individuals and could contribute to racial disparities in healthcare delivery—or even runs the risk of reifying race in a way that suggests more biological significance than it deserves.

That’s why I was pleased recently to see the results of two NIH-supported studies published in The New England Journal of Medicine that suggest a way to take race out of the kidney disease equation [1, 2]. The approach involves a new equation that swaps out one blood test for another and doesn’t ask about race.

For a variety of reasons, including socioeconomic issues and access to healthcare, CKD disproportionately affects the Black community. In fact, Blacks with the condition are also almost four times more likely than whites to develop kidney failure. That’s why Blacks with CKD must visit their doctors regularly to monitor their kidney function, and often that visit involves eGFR.

The blood test used in eGFR measures creatinine, a waste product produced from muscle. For about the past 20 years, a few points have been automatically added to the score of African Americans, based on data showing that adults who identify as Black, on average, have a higher baseline level of circulating creatinine. But adjusting the score upward toward normal function runs the risk of making the kidneys seem a bit healthier than they really are and delaying life-preserving dialysis or getting on a transplant list.

A team led by Chi-yuan Hsu, University of California, San Francisco, took a closer look at the current eGFR calculations. The researchers used long-term data from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study, an NIH-supported prospective, observational study of nearly 4,000 racially and ethnically diverse patients with CKD in the U.S. The study design specified that about 40 percent of its participants should identify as Black.

To look for race-free ways to measure kidney function, the researchers randomly selected more than 1,400 of the study’s participants to undergo a procedure that allows kidney function to be measured directly instead of being estimated based on blood tests. The goal was to develop an accurate approach to estimating GFR, the rate of fluid flow through the kidneys, from blood test results that didn’t rely on race.

Their studies showed that simply omitting race from the equation would underestimate GFR in Black study participants. The best solution, they found, was to calculate eGFR based on cystatin C, a small protein that the kidneys filter from the blood, in place of the standard creatinine. Estimation of GFR using cystatin C generated similarly accurate results but without the need to factor in race.

The second NIH-supported study led by Lesley Inker, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, came to similar conclusions. They set out to develop new equations without race using data from several prior studies. They then compared the accuracy of their new eGFR equations to measured GFR in a validation set of 12 other studies, including about 4,000 participants.

Their findings show that currently used equations that include race, sex, and age overestimated measured GFR in Black Americans. However, taking race out of the equation without other adjustments underestimated measured GFR in Black people. Equations including both creatinine and cystatin C, but omitting race, were more accurate. The new equations also led to smaller estimated differences between Black and non-Black study participants.

The hope is that these findings will build momentum toward widespread adoption of cystatin C for estimating GFR. Already, a national task force has recommended immediate implementation of a new diagnostic equation that eliminates race and called for national efforts to increase the routine and timely measurement of cystatin C [3]. This will require a sea change in the standard measurements of blood chemistries in clinical and hospital labs—where creatinine is routinely measured, but cystatin C is not. As these findings are implemented into routine clinical care, let’s hope they’ll reduce health disparities by leading to more accurate and timely diagnosis, supporting the goals of precision health and encouraging treatment of CKD for all people, regardless of their race.

References:

[1] Race, genetic ancestry, and estimating kidney function in CKD. Hsu CY, Yang W, Parikh RV, Anderson AH, Chen TK, Cohen DL, He J, Mohanty MJ, Lash JP, Mills KT, Muiru AN, Parsa A, Saunders MR, Shafi T, Townsend RR, Waikar SS, Wang J, Wolf M, Tan TC, Feldman HI, Go AS; CRIC Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2021 Sep 23.

[2] New creatinine- and cystatin C-based equations to estimate GFR without race. Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, Tighiouart H, Wang D, Sang Y, Crews DC, Doria A, Estrella MM, Froissart M, Grams ME, Greene T, Grubb A, Gudnason V, Gutiérrez OM, Kalil R, Karger AB, Mauer M, Navis G, Nelson RG, Poggio ED, Rodby R, Rossing P, Rule AD, Selvin E, Seegmiller JC, Shlipak MG, Torres VE, Yang W, Ballew SH,Couture SJ, Powe NR, Levey AS; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. N Engl J Med. 2021 Sep 23.

[3] A unifying approach for GFR estimation: recommendations of the NKF-ASN Task Force on Reassessing the Inclusion of Race in Diagnosing Kidney Disease. Delgado C, Baweja M, Crews DC, Eneanya ND, Gadegbeku CA, Inker LA, Mendu ML, Miller WG, Moxey-Mims MM, Roberts GV, St Peter WL, Warfield C, Powe NR. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021 Sep 22:S0272-6386(21)00828-3.

Links:

Chronic Kidney Disease (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Explaining Your Kidney Test Results: A Tool for Clinical Use (NIDDK)

Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study

Chi-yuan Hsu (University of California, San Francisco)

Lesley Inker (Tufts Medical Center, Boston)

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Posted In: News

Tags: African American health, African Americans, blacks, chronic kidney disease, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study, CKD, creatinine, CRIC Study, cystatin C, diagnostics, eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate, genetics, GFR, glomerular filtration rate, health disparities, kidney dialysis, kidney disease, kidney failure, kidney transplantation, kidneys, muscle, precision health, precision medicine, race, renal failure

How Severe COVID-19 Can Tragically Lead to Lung Failure and Death

Posted on May 11th, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

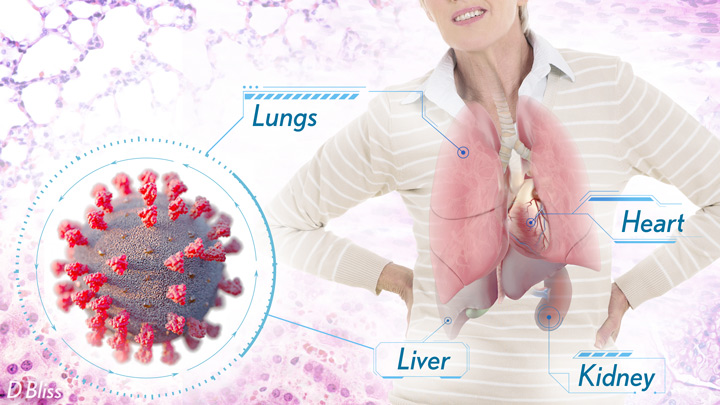

More than 3 million people around the world, now tragically including thousands every day in India, have lost their lives to severe COVID-19. Though incredible progress has been made in a little more than a year to develop effective vaccines, diagnostic tests, and treatments, there’s still much we don’t know about what precisely happens in the lungs and other parts of the body that leads to lethal outcomes.

Two recent studies in the journal Nature provide some of the most-detailed analyses yet about the effects on the human body of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 [1,2]. The research shows that in people with advanced infections, SARS-CoV-2 often unleashes a devastating series of host events in the lungs prior to death. These events include runaway inflammation and rampant tissue destruction that the lungs cannot repair.

Both studies were supported by NIH. One comes from a team led by Benjamin Izar, Columbia University, New York. The other involves a group led by Aviv Regev, now at Genentech, and formerly at Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA.

Each team analyzed samples of essential tissues gathered from COVID-19 patients shortly after their deaths. Izar’s team set up a rapid autopsy program to collect and freeze samples within hours of death. He and his team performed single-cell RNA sequencing on about 116,000 cells from the lung tissue of 19 men and women. Similarly, Regev’s team developed an autopsy biobank that included 420 total samples from 11 organ systems, which were used to generate multiple single-cell atlases of tissues from the lung, kidney, liver, and heart.

Izar’s team found that the lungs of people who died of COVID-19 were filled with immune cells called macrophages. While macrophages normally help to fight an infectious virus, they seemed in this case to produce a vicious cycle of severe inflammation that further damaged lung tissue. The researchers also discovered that the macrophages produced high levels of IL-1β, a type of small inflammatory protein called a cytokine. This suggests that drugs to reduce effects of IL-1β might have promise to control lung inflammation in the sickest patients.

As a person clears and recovers from a typical respiratory infection, such as the flu, the lung repairs the damage. But in severe COVID-19, both studies suggest this isn’t always possible. Not only does SARS-CoV-2 destroy cells within air sacs, called alveoli, that are essential for the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide, but the unchecked inflammation apparently also impairs remaining cells from repairing the damage. In fact, the lungs’ regenerative cells are suspended in a kind of reparative limbo, unable to complete the last steps needed to replace healthy alveolar tissue.

In both studies, the lung tissue also contained an unusually large number of fibroblast cells. Izar’s team went a step further to show increased numbers of a specific type of pathological fibroblast, which likely drives the rapid lung scarring (pulmonary fibrosis) seen in severe COVID-19. The findings point to specific fibroblast proteins that may serve as drug targets to block deleterious effects.

Regev’s team also describes how the virus affects other parts of the body. One surprising discovery was there was scant evidence of direct SARS-CoV-2 infection in the liver, kidney, or heart tissue of the deceased. Yet, a closer look heart tissue revealed widespread damage, documenting that many different coronary cell types had altered their genetic programs. It’s still to be determined if that’s because the virus had already been cleared from the heart prior to death. Alternatively, the heart damage might not be caused directly by SARS-CoV-2, and may arise from secondary immune and/or metabolic disruptions.

Together, these two studies provide clearer pictures of the pathology in the most severe and lethal cases of COVID-19. The data from these cell atlases has been made freely available for other researchers around the world to explore and analyze. The hope is that these vast data sets, together with future analyses and studies of people who’ve tragically lost their lives to this pandemic, will improve our understanding of long-term complications in patients who’ve survived. They also will now serve as an important foundational resource for the development of promising therapies, with the goal of preventing future complications and deaths due to COVID-19.

References:

[1] A molecular single-cell lung atlas of lethal COVID-19. Melms JC, Biermann J, Huang H, Wang Y, Nair A, Tagore S, Katsyv I, Rendeiro AF, Amin AD, Schapiro D, Frangieh CJ, Luoma AM, Filliol A, Fang Y, Ravichandran H, Clausi MG, Alba GA, Rogava M, Chen SW, Ho P, Montoro DT, Kornberg AE, Han AS, Bakhoum MF, Anandasabapathy N, Suárez-Fariñas M, Bakhoum SF, Bram Y, Borczuk A, Guo XV, Lefkowitch JH, Marboe C, Lagana SM, Del Portillo A, Zorn E, Markowitz GS, Schwabe RF, Schwartz RE, Elemento O, Saqi A, Hibshoosh H, Que J, Izar B. Nature. 2021 Apr 29.

[2] COVID-19 tissue atlases reveal SARS-CoV-2 pathology and cellular targets. Delorey TM, Ziegler CGK, Heimberg G, Normand R, Shalek AK, Villani AC, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Regev A. et al. Nature. 2021 Apr 29.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Izar Lab (Columbia University, New York)

Aviv Regev (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA)

NIH Support: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Posted In: News

Tags: alveoli, biobank, coronavirus, COVID-19, COVID-19 pathology, cytokines, drug targets, fibroblasts, heart, kidneys, liver, lungs, macrophage, novel coronavirus, pandemic, pulmonary fibrosis, SARS-CoV-2, severe COVID-19, single cell analysis, single-cell atlas, tissue samples

Study Ties COVID-19-Related Syndrome in Kids to Altered Immune System

Posted on September 1st, 2020 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: iStock/Sasiistock

Most children infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, develop only a mild illness. But, days or weeks later, a small percentage of kids go on to develop a puzzling syndrome known as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). This severe inflammation of organs and tissues can affect the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, skin, and eyes.

Thankfully, most kids with MIS-C respond to treatment and make rapid recoveries. But, tragically, MIS-C can sometimes be fatal.

With COVID-19 cases in children having increased by 21 percent in the United States since early August [2], NIH and others are continuing to work hard on getting a handle on this poorly understood complication. Many think that MIS-C isn’t a direct result of the virus, but seems more likely to be due to an intense autoimmune response. Indeed, a recent study in Nature Medicine [1] offers some of the first evidence that MIS-C is connected to specific changes in the immune system that, for reasons that remain mysterious, sometimes follow COVID-19.

These findings come from Shane Tibby, a researcher at Evelina London Children’s Hospital, London. United Kingdom; Manu Shankar-Hari, a scientist at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London; and colleagues. The researchers enlisted 25 children, ages 7 to 14, who developed MIS-C in connection with COVID-19. In search of clues, they examined blood samples collected from the children during different stages of their care, starting when they were most ill through recovery and follow-up. They then compared the samples to those of healthy children of the same ages.

What they found was a complex array of immune disruptions. The children had increased levels of various inflammatory molecules known as cytokines, alongside raised levels of other markers suggesting tissue damage—such as troponin, which indicates heart muscle injury.

The neutrophils, monocytes, and other white blood cells that rapidly respond to infections were activated as expected. But the levels of certain white blood cells called T lymphocytes were paradoxically reduced. Interestingly, despite the low overall numbers of T lymphocytes, particular subsets of them appeared activated as though fighting an infection. While the children recovered, those differences gradually disappeared as the immune system returned to normal.

It has been noted that MIS-C bears some resemblance to an inflammatory condition known as Kawasaki disease, which also primarily affects children. While there are similarities, this new work shows that MIS-C is a distinct illness associated with COVID-19. In fact, only two children in the study met the full criteria for Kawasaki disease based on the clinical features and symptoms of their illness.

Another recent study from the United Kingdom, reported several new symptoms of MIS-C [3]. They include headaches, tiredness, muscle aches, and sore throat. Researchers also determined that the number of platelets was much lower in the blood of children with MIS-C than in those without the condition. They proposed that evaluating a child’s symptoms along with his or her platelet level could help to diagnose MIS-C.

It will now be important to learn much more about the precise mechanisms underlying these observed changes in the immune system and how best to treat or prevent them. In support of this effort, NIH recently announced $20 million in research funding dedicated to the development of approaches that identify children at high risk for developing MIS-C [4].

The hope is that this new NIH effort, along with other continued efforts around the world, will elucidate the factors influencing the likelihood that a child with COVID-19 will develop MIS-C. Such insights are essential to allow doctors to intervene as early as possible and improve outcomes for this potentially serious condition.

References:

[1] Peripheral immunophenotypes in children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Carter MJ, Fish M, Jennings A, Doores KJ, Wellman P, Seow J, Acors S, Graham C, Timms E, Kenny J, Neil S, Malim MH, Tibby SM, Shankar-Hari M. Nat Med. 2020 Aug 18.

[2] Children and COVID-19: State-Level Data Report. American Academy of Pediatrics. August 24, 2020.

[3] Clinical characteristics of children and young people admitted to hospital with covid-19 in United Kingdom: prospective multicentre observational cohort study. Swann OV, Holden KA, Turtle L, Harrison EW, Docherty AB, Semple MG, et al. Br Med J. 2020 Aug 17.

[4] NIH-funded project seeks to identify children at risk for MIS-C. NIH. August 7, 2020.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Kawasaki Disease (Genetic and Rare Disease Information Center/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Shane Tibby (Evelina London Children’s Hospital, London)

Manu Shankar-Hari (King’s College, London)

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Office of the Director; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities; Fogarty International Center

Posted In: News

Tags: autoimmunity, blood platelets, brain, children, coronavirus, COVID-19, COVID-19 treatment, cytokines, heart, Kawasaki disease, kidneys, lungs, lymphocytes, MIS-C, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, novel coronavirus, pediatrics, PreVAIL kids, SARS-CoV-2, T cells, troponin

NASA Twins Study Reveals Health Effects of Space Flight

Posted on April 23rd, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

Sending one identical twin into space while the other stays behind on Earth might sound like the plot of a sci-fi thriller. But it’s actually a setup for some truly fascinating scientific research!

As part of NASA’s landmark Twins Study, Scott Kelly became the first U.S. astronaut to spend nearly a year in “weightless” microgravity conditions aboard the International Space Station. Meanwhile, his identical twin, retired astronaut Mark Kelly, remained earthbound. Researchers put both men—who like all identical twins shared the same genetic makeup at birth—through the same battery of biomedical tests to gauge how the human body responds to life in space. The good news for the future of space travel is that the results indicated that health is “mostly sustained” during a prolonged stay in space.

Reporting in the journal Science, the Twins Study team, which included several NIH-funded researchers, detailed many thousands of differences between the Kelly twins at the molecular, cellular, and physiological levels during the 340-day observation period. However, most of Scott’s measures returned to near pre-flight levels within six months of rejoining Mark on Earth.

Over the past nearly 60 years, 559 people have flown in space. While weightless conditions are known to speed various processes associated with aging, few astronauts have remained in space for more than a few months at a time. With up to three year missions to the moon or Mars planned for the future, researchers want to get a better sense of how the human body will hold up under microgravity conditions for longer periods.

To get a more holistic answer, researchers collected a variety of biological samples from the Kelly twins before, during, and after Scott’s spaceflight. All told, more than 300 samples were collected over the course of 27 months.

Multiple labs around the country used state-of-the art tools to examine those samples in essentially every way they could think of doing. Those analyses offer a remarkably detailed view of changes in an astronaut’s biology and health while in space.

With so much data, there were lots of interesting findings to report, including many changes in the expression of Scott’s genes that weren’t observed in his twin. While most of these changes returned to preflight levels within six months of Scott’s return to Earth, about 7 percent of his genes continued to be expressed at different levels. These included some related to DNA repair and the immune system.

Despite those changes in immunity-related gene expression, his immune system appeared to remain fully functional. His body responded to the flu vaccine administered in space just as would be expected back home on Earth.

Scott also had some measurable changes in telomeres—complexes of specialized DNA sequences, RNA, and protein that protect the tips of our chromosomes. These generally shorten a bit each time cells divide. But during the time in space, the telomeres in Scott’s white blood cells measured out at somewhat greater length.

Potentially, this is because some of his stem cells, which are younger and haven’t gone through as many cell divisions, were being released into the blood. Back on Earth, his telomere lengths returned to an average length within six months of his return. Over the course of the study, the earthbound telomeres of his twin brother Mark remained stable.

Researchers also uncovered small but significant changes to Scott’s gut microbiome, the collection of microbes that play important roles in digestion and the immune system. More specifically, there was a shift in the ratio of two major groups of bacteria. Once back on Earth, his microbiome quickly shifted back to its original preflight state.

The data also provided some metabolic evidence suggesting that Scott’s mitochondria, the cellular powerhouses that supply the body with energy, weren’t functioning at full capacity in space. While further study is needed, the NIH-funded team led by Kumar Sharma, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, suggests that changes in the mitochondria might underlie changes often seen in space to the human cardiovascular system, kidneys, and eyes.

Of course, such a small, two-person study makes it hard to draw any general conclusions about human health in space. But the comparisons certainly help to point us in the right direction. They provide a framework for understanding how the human body responds on a molecular and cellular level to microgravity over time. They also may hold important lessons for understanding human health and precision medicine down here on Earth.

I look forward to future space missions and their contributions to biomedical research. I’m also happy to report, it will be a short wait.

Last year, I highlighted the Tissue Chips in Space Initiative. It’s a unique collaboration between NIH and NASA in which dozens of human tissue chips—tiny, 3D devices bioengineered to model different tissues and organs—will be sent to the International Space Station to study the accelerated aging that occurs in space.

The first tissue chips were sent to the International Space Station last December. And I’m pleased to report that more were aboard recently when the SpaceX Dragon cargo spacecraft made a resupply run to the International Space Station. On May 8, astronauts there successfully completed offloading miniaturized tissue chips of the lungs, bone marrow, and kidneys, enabling more truly unique science in low gravity that couldn’t be performed down here on Earth.

Reference:

[1] The NASA Twins Study: A multidimensional analysis of a year-long human spaceflight. Garrett-Bakelman FE, Darshi M, Green SJ, Gur RC, Lin L, Macias BR, et. al. Science. 2019 Apr 12;364(6436).

Links:

Twins Study (NASA)

Launches and Landings (NASA. Washington, D.C.)

Kumar Sharma (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio)

Tissue Chips in Space (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Posted In: News

Tags: aging, astronauts, bone marrow, flu vaccine, genes, identical twins, immunity, International Space Station, kidneys, lungs, Mars, microbiome, microgravity, mitochondria, Moon, NASA, space, spaceflight, telomeres, tissue chips, Tissue Chips in Space, twins, Twins Study, weightlessness

H3Africa: Fostering Collaboration

Posted on March 23rd, 2017 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Pioneers in building Africa’s genomic research capacity; front, Charlotte Osafo (l) and Yemi Raji; back, David Burke (l) and Tom Glover.

Credit: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

About a year ago, Tom Glover began sifting through a stack of applications from prospective students hoping to be admitted into the Master’s Degree Program in Human Genetics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Glover, the program’s director, got about halfway through the stack when he noticed applications from two physicians in West Africa: Charlotte Osafo from Ghana, and Yemi Raji from Nigeria. Both were kidney specialists in their 40s, and neither had formal training in genomics or molecular biology, which are normally requirements for entry into the program.

Glover’s first instinct was to disregard the applications. But he noticed the doctors were affiliated with the Human Heredity and Health in Africa (H3Africa) Initiative, which is co-supported by the Wellcome Trust and the National Institutes of Health Common Fund, and aims in part to build the expertise to carry out genomics research across the continent of Africa. (I am proud to have had a personal hand in the initial steps that led to the founding of H3Africa.) Glover held onto the two applications and, after much internal discussion, Osafo and Raji were admitted to the Master’s Program. But there were important stipulations: they had to arrive early to undergo “boot camp” in genomics and molecular biology and also extend their coursework over an extra term.

Posted In: Health, Science, Training

Tags: Africa, chronic kidney disease, genomics, global health, H3Africa, human genetics, Human Heredity and Health in Africa Initiative, kidneys, molecular biology, nephrology, research training, sub-Saharan Africa, West Africa

Metabolomics: Taking Aim at Diabetic Kidney Failure

Posted on January 23rd, 2014 by Dr. Francis Collins

iStock

Caption: Dialysis is often used to treat kidney failure related to diabetes.

My own research laboratory has worked on the genetics of diabetes for two decades. One of my colleagues from those early days, Andrzej Krolewski, a physician-scientist at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston, wondered why about one-third of people with type 2 diabetes eventually develop kidney damage that progresses to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), but others don’t. A stealthy condition that can take years for symptoms to appear, ESRD occurs when the kidneys fail, allowing toxic wastes to build up. The only treatments available are dialysis or kidney transplants.

Tags: biomarkers, diabetes, end-stage renal disease, ESRD, kidney failure, kidneys, metabolites, metabolomics, type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes