mAbs – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

Charting a Rapid Course Toward Better COVID-19 Tests and Treatments

Posted on August 6th, 2020 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Quidel; iStock/xavierarnau

It is becoming apparent that our country is entering a new and troubling phase of the pandemic as SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, continues to spread across many states and reaches into both urban and rural communities. This growing community spread is hard to track because up to 40 percent of infected people seem to have no symptoms. They can pass the virus quickly and unsuspectingly to friends and family members who might be more vulnerable to becoming seriously ill. That’s why we should all be wearing masks when we go out of the house—none of us can be sure we’re not that asymptomatic carrier of the virus.

This new phase makes fast, accessible, affordable diagnostic testing a critical first step in helping people and communities. In recognition of this need, NIH’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) initiative, just initiated in late April, has issued an urgent call to the nation’s inventors and innovators to develop fast, easy-to-use tests for SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. It brought a tremendous response, and NIH selected about 100 of the best concepts for an intense one-week “shark-tank” technology evaluation process.

Moving ahead at an unprecedented pace, NIH last week announced the first RADx projects to come through the deep dive with flying colors and enter the scale-up process necessary to provide additional rapid testing capacity to the U.S. public. As part of the RADx initiative, seven biomedical technology companies will receive a total of $248.7 million in federal stimulus funding to accelerate their efforts to scale up new lab-based and point-of-care technologies.

Four of these projects will aim to bolster the nation’s lab-based COVID-19 diagnostics capacity by tens of thousands of tests per day as soon as September and by millions by the end of the year. The other three will expand point-of-care testing for COVID-19, making results more rapidly and readily available in doctor’s offices, urgent care clinics, long-term care facilities, schools, child care centers, or even at home.

This is only a start, and we expect that more RADx projects will advance in the coming months and begin scaling up for wide-scale use. In the meantime, here’s an overview of the first seven projects developed through the initiative, which NIH is carrying out in partnership with the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Health, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, and the Department of Defense:

Point-of-Care Testing Approaches

Mesa Biotech. Hand-held testing device detects the genetic material of SARS-CoV-2. Results are read from a removable, single-use cartridge in 30 minutes.

Quidel. Test kit detects protein (viral antigen) from SARS-CoV-2. Electronic analyzers provide results within 15 minutes. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Service has identified this technology for possible use in nursing homes.

Talis Biomedical. Compact testing instrument uses a multiplexed cartridge to detect the genetic material of SARS-CoV-2 through isothermal amplification. Optical detection system delivers results in under 30 minutes.

Lab-based Testing Approaches

Ginkgo Bioworks. Automated system uses next-generation sequencing to scan patient samples for SARS-CoV-2’s genetic material. This system will be scaled up to make it possible to process tens of thousands of tests simultaneously and deliver results within one to two days. The company’s goal is to scale up to 50,000 tests per day in September and 100,000 per day by the end of 2020.

Helix OpCo. By combining bulk shipping of test kits and patient samples, automation, and next-generation sequencing of genetic material, the company’s goal is to process up to 50,000 samples per day by the end of September and 100,000 per day by the end of 2020.

Fluidigm. Microfluidics platform with the capacity to process thousands of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for SARS-CoV-2 genetic material per day. The company’s goal is to scale up this platform and deploy advanced integrated fluidic chips to provide tens to hundreds of thousands of new tests per day in the fall of 2020. Most tests will use saliva.

Mammoth Biosciences. System uses innovative CRISPR gene-editing technology to detect key pieces of SARS-CoV-2 genetic material in patient samples. The company’s goal is to provide a multi-fold increase in testing capacity in commercial laboratories.

At the same time, on the treatment front, significant strides continue to be made by a remarkable public-private partnership called Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV). Since its formation in May, the partnership, which involves 20 biopharmaceutical companies, academic experts, and multiple federal agencies, has evaluated hundreds of therapeutic agents with potential application for COVID-19 and prioritized the most promising candidates.

Among the most exciting approaches are monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), which are biologic drugs derived from neutralizing antibodies isolated from people who’ve survived COVID-19. This week, the partnership launched two trials (one for COVID-19 inpatients, the other for COVID-19 outpatients) of a mAB called LY-CoV555, which was developed by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN. It was discovered by Lilly’s development partner AbCellera Biologics Inc. Vancouver, Canada, in collaboration with the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). In addition to the support from ACTIV, both of the newly launched studies also receive support for Operation Warp Speed, the government’s multi-agency effort against COVID-19.

LY-CoV555 was derived from the immune cells of one of the very first survivors of COVID-19 in the United States. It targets the spike protein on the surface of SARS-CoV-2, blocking it from attaching to human cells.

The first trial, which will look at both the safety and efficacy of the mAb for treating COVID-19, will involve about 300 individuals with mild to moderate COVID-19 who are hospitalized at facilities that are part of existing clinical trial networks. These volunteers will receive either an intravenous infusion of LY-CoV555 or a placebo solution. Five days later, their condition will be evaluated. If the initial data indicate that LY-CoV555 is safe and effective, the trial will transition immediately—and seamlessly—to enrolling an additional 700 participants with COVID-19, including some who are severely ill.

The second trial, which will evaluate how LY-CoV555 affects the early course of COVID-19, will involve 220 individuals with mild to moderate COVID-19 who don’t need to be hospitalized. In this study, participants will randomly receive either an intravenous infusion of LY-CoV555 or a placebo solution, and will be carefully monitored over the next 28 days. If the data indicate that LY-CoV555 is safe and shortens the course of COVID-19, the trial will then enroll an additional 1,780 outpatient volunteers and transition to a study that will more broadly evaluate its effectiveness.

Both trials are later expected to expand to include other experimental therapies under the same master study protocol. Master protocols allow coordinated and efficient evaluation of multiple investigational agents at multiple sites as the agents become available. These protocols are designed with a flexible, rapidly responsive framework to identify interventions that work, while reducing administrative burden and cost.

In addition, Lilly this week started a separate large-scale safety and efficacy trial to see if LY-CoV555 can be used to prevent COVID-19 in high-risk residents and staff at long-term care facilities. The study isn’t part of ACTIV.

NIH-funded researchers have been extremely busy over the past seven months, pursuing every avenue we can to detect, treat, and, ultimately, end this devasting pandemic. Far more work remains to be done, but as RADx and ACTIV exemplify, we’re making rapid progress through collaboration and a strong, sustained investment in scientific innovation.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx)

Video: NIH RADx Delivering New COVID-19 Testing Technologies to Meet U.S. Demand (YouTube)

Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV)

Explaining Operation Warp Speed (U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources/Washington, D.C.)

“NIH delivering new COVID-19 testing technologies to meet U.S. demand,” NIH news release,” July 31, 2020.

“NIH launches clinical trial to test antibody treatment in hospitalized COVID-19 patients,” NIH new release, August 4, 2020.

“NIH clinical trial to test antibodies and other experimental therapeutics for mild and moderate COVID-19,” NIH news release, August 4, 2020.

Posted In: News

Tags: AbCellerra Biologics, Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines, ACTIV, antibodies, coronavirus, COVID-19, COVID-19 testing, COVID-19 treatment, diagnostics, Eli Lilly and Company, Fluidigm, Gingko Bioworks, Helix OpCo, lab-based testing, LY-CoV555, mAbs, Mammoth Biosciences, master protocols, Mesa Biotech, monoclonal antibody, novel coronavirus, Operation Warp Speed, pandemic, point-of-care tests, Quidel, RADx, Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics Initiative, saliva test, SARS-CoV-2, spike protein, Talis Biomedical, therapeutics

Enlisting Monoclonal Antibodies in the Fight Against COVID-19

Posted on May 21st, 2020 by Dr. Francis Collins

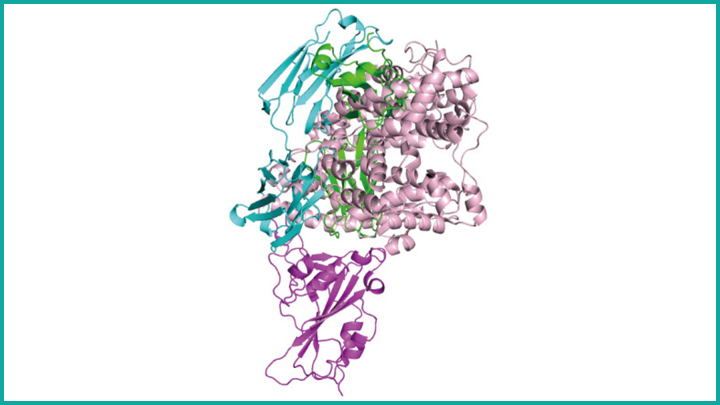

Caption: Antibody Binding to SARS-CoV-2. Structural illustration of B38 antibody (cyan, green) attached to receptor-binding domain of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (magenta). B38 blocks SARS-CoV-2 from binding to the ACE2 receptor (light pink) of a human cell, ACE2 is what the virus uses to infect cells. Credit: Y. Wu et al. Science, 2020

We now know that the immune system of nearly everyone who recovers from COVID-19 produces antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes this easily transmitted respiratory disease [1]. The presence of such antibodies has spurred hope that people exposed to SARS-CoV-2 may be protected, at least for a time, from getting COVID-19 again. But, in this post, I want to examine another potential use of antibodies: their promise for being developed as therapeutics for people who are sick with COVID-19.

In a recent paper in the journal Science, researchers used blood drawn from a COVID-19 survivor to identify a pair of previously unknown antibodies that specifically block SARS-CoV-2 from attaching to human cells [2]. Because each antibody locks onto a slightly different place on SARS-CoV-2, the vision is to use these antibodies in combination to block the virus from entering cells, thereby curbing COVID-19’s destructive spread throughout the lungs and other parts of the body.

The research team, led by Yan Wu, Capital Medical University, Beijing, first isolated the pair of antibodies in the laboratory, starting with white blood cells from the patient. They were then able to produce many identical copies of each antibody, referred to as monoclonal antibodies. Next, these monoclonal antibodies were simultaneously infused into a mouse model that had been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Just one infusion of this combination antibody therapy lowered the amount of viral genetic material in the animals’ lungs by as much as 30 percent compared to the amount in untreated animals.

Monoclonal antibodies are currently used to treat a variety of conditions, including asthma, cancer, Crohn’s disease, and rheumatoid arthritis. One advantage of this class of therapeutics is that the timelines for their development, testing, and approval are typically shorter than those for drugs made of chemical compounds, called small molecules. Because of these and other factors, many experts think antibody-based therapies may offer one of the best near-term options for developing safe, effective treatments for COVID-19.

So, what exactly led up to this latest scientific achievement? The researchers started out with a snippet of SARS-CoV-2’s receptor binding domain (RBD), a vital part of the spike protein that protrudes from the virus’s surface and serves to dock the virus onto an ACE2 receptor on a human cell. In laboratory experiments, the researchers used the RBD snippet as “bait” to attract antibody-producing B cells in a blood sample obtained from the COVID-19 survivor. Altogether, the researchers identified four unique antibodies, but two, which they called B38 and H4, displayed a synergistic action in binding to the RBD that made them stand out for purposes of therapeutic development and further testing.

To complement their lab and animal experiments, the researchers used a particle accelerator called a synchrotron to map, at near-atomic resolution, the way in which the B38 antibody locks onto its viral target. This structural information helps to clarify the precise biochemistry of the complex interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and the antibody, providing a much-needed guide for the rational design of targeted drugs and vaccines. While more research is needed before this or other monoclonal antibody therapies can be used in humans suffering from COVID-19, the new work represents yet another example of how basic science is expanding fundamental knowledge to advance therapeutic discovery for a wide range of health concerns.

Meanwhile, there’s been other impressive recent progress towards the development of monoclonal antibody therapies for COVID-19. In work described in the journal Nature, an international research team started with a set of neutralizing antibodies previously identified in a blood sample from a person who’d recovered from a different coronavirus-caused disease, called severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), in 2003 [3]. Through laboratory and structural imaging studies, the researchers found that one of these antibodies, called S309, proved particularly effective at neutralizing the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, because of its potent ability to target the spike protein that enables the virus to enter cells. The team, which includes NIH grantees David Veesler, University of Washington, Seattle, and Davide Corti, Humabs Biomed, a subsidiary of Vir Biotechnology, has indicated that S309 is already on an accelerated development path toward clinical trials.

In the U.S. and Europe, the Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) partnership, which has brought together public and private sector COVID-19 therapeutic and vaccine efforts, is intensely pursuing the development and testing of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies for COVID-19 [4]. Stay tuned for more information about these potentially significant advances in the next few months.

References:

[1] Humoral immune response and prolonged PCR positivity in a cohort of 1343 SARS-CoV 2 patients in the New York City region. Wajnberg A , Mansour M, Leven E, Bouvier NM, Patel G, Firpo A, Mendu R, Jhang J, Arinsburg S, Gitman M, Houldsworth J, Baine I, Simon V, Aberg J, Krammer F, Reich D, Cordon-Cardo C. medRxiv. Preprint Posted May 5, 2020.

[2] A noncompeting pair of human neutralizing antibodies block COVID-19 virus binding to its receptor ACE2. Wu Y. et al., Science. 13 May 2020 [Epub ahead of publication]

[3] Cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by a human monoclonal SARS-CoV antibody. Pinto D, Park YJ, Beltramello M, Veesler D, Cortil D, et al. Nature. 18 May 2020 [Epub ahead of print]

[4] Accelerating COVID-19 therapeutic interventions and vaccines (ACTIV): An unprecedented partnership for unprecedented times. Collins FS, Stoffels P. JAMA. 2020 May 18.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Monoclonal Antibodies (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Posted In: News

Tags: ACE2, ACTIV, antibodies, antibody treatment, B cells, biochemistry, China, coronavirus, COVID-19, drug design, drug development, immunology, mAbs, monoclonal antibody, novel coronavirus, pandemic, SARS-CoV-2, spike protein, structural biology, synchrotron X-ray fluorescence technology