muscle – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

Millions of Single-Cell Analyses Yield Most Comprehensive Human Cell Atlas Yet

Posted on May 24th, 2022 by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

There are 37 trillion or so cells in our bodies that work together to give us life. But it may surprise you that we still haven’t put a good number on how many distinct cell types there are within those trillions of cells.

That’s why in 2016, a team of researchers from around the globe launched a historic project called the Human Cell Atlas (HCA) consortium to identify and define the hundreds of presumed distinct cell types in our bodies. Knowing where each cell type resides in the body, and which genes each one turns on or off to create its own unique molecular identity, will revolutionize our studies of human biology and medicine across the board.

Since its launch, the HCA has progressed rapidly. In fact, it has already reached an important milestone with the recent publication in the journal Science of four studies that, together, comprise the first multi-tissue drafts of the human cell atlas. This draft, based on analyses of millions of cells, defines more than 500 different cell types in more than 30 human tissues. A second draft, with even finer definition, is already in the works.

Making the HCA possible are recent technological advances in RNA sequencing. RNA sequencing is a topic that’s been mentioned frequently on this blog in a range of research areas, from neuroscience to skin rashes. Researchers use it to detect and analyze all the messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules in a biological sample, in this case individual human cells from a wide range of tissues, organs, and individuals who voluntarily donated their tissues.

By quantifying these RNA messages, researchers can capture the thousands of genes that any given cell actively expresses at any one time. These precise gene expression profiles can be used to catalogue cells from throughout the body and understand the important similarities and differences among them.

In one of the published studies, funded in part by the NIH, a team co-led by Aviv Regev, a founding co-chair of the consortium at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, established a framework for multi-tissue human cell atlases [1]. (Regev is now on leave from the Broad Institute and MIT and has recently moved to Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, CA.)

Among its many advances, Regev’s team optimized single-cell RNA sequencing for use on cell nuclei isolated from frozen tissue. This technological advance paved the way for single-cell analyses of the vast numbers of samples that are stored in research collections and freezers all around the world.

Using their new pipeline, Regev and team built an atlas including more than 200,000 single-cell RNA sequence profiles from eight tissue types collected from 16 individuals. These samples were archived earlier by NIH’s Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. The team’s data revealed unexpected differences among cell types but surprising similarities, too.

For example, they found that genetic profiles seen in muscle cells were also present in connective tissue cells in the lungs. Using novel machine learning approaches to help make sense of their data, they’ve linked the cells in their atlases with thousands of genetic diseases and traits to identify cell types and genetic profiles that may contribute to a wide range of human conditions.

By cross-referencing 6,000 genes previously implicated in causing specific genetic disorders with their single-cell genetic profiles, they identified new cell types that may play unexpected roles. For instance, they found some non-muscle cells that may play a role in muscular dystrophy, a group of conditions in which muscles progressively weaken. More research will be needed to make sense of these fascinating, but vital, discoveries.

The team also compared genes that are more active in specific cell types to genes with previously identified links to more complex conditions. Again, their data surprised them. They identified new cell types that may play a role in conditions such as heart disease and inflammatory bowel disease.

Two of the other papers, one of which was funded in part by NIH, explored the immune system, especially the similarities and differences among immune cells that reside in specific tissues, such as scavenging macrophages [2,3] This is a critical area of study. Most of our understanding of the immune system comes from immune cells that circulate in the bloodstream, not these resident macrophages and other immune cells.

These immune cell atlases, which are still first drafts, already provide an invaluable resource toward designing new treatments to bolster immune responses, such as vaccines and anti-cancer treatments. They also may have implications for understanding what goes wrong in various autoimmune conditions.

Scientists have been working for more than 150 years to characterize the trillions of cells in our bodies. Thanks to this timely effort and its advances in describing and cataloguing cell types, we now have a much better foundation for understanding these fundamental units of the human body.

But the latest data are just the tip of the iceberg, with vast flows of biological information from throughout the human body surely to be released in the years ahead. And while consortium members continue making history, their hard work to date is freely available to the scientific community to explore critical biological questions with far-reaching implications for human health and disease.

References:

[1] Single-nucleus cross-tissue molecular reference maps toward understanding disease gene function. Eraslan G, Drokhlyansky E, Anand S, Fiskin E, Subramanian A, Segrè AV, Aguet F, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Ardlie KG, Regev A, et al. Science. 2022 May 13;376(6594):eabl4290.

[2] Cross-tissue immune cell analysis reveals tissue-specific features in humans. Domínguez Conde C, Xu C, Jarvis LB, Rainbow DB, Farber DL, Saeb-Parsy K, Jones JL,Teichmann SA, et al. Science. 2022 May 13;376(6594):eabl5197.

[3] Mapping the developing human immune system across organs. Suo C, Dann E, Goh I, Jardine L, Marioni JC, Clatworthy MR, Haniffa M, Teichmann SA, et al. Science. 2022 May 12:eabo0510.

Links:

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Studying Cells (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Regev Lab (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Cancer Institute; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Eye Institute

Tags: autoimmune disorders, cell biology, cell reference maps, cells, connective tissue, genotype-tissue expression, GTEx, HCA, heart disease, Human Cell Atlas, immunology, inflammatory bowel disease, lungs, machine learning, macrophage, messenger RNA, mRNA, muscle, muscular dystrophy, RNA, RNA sequencing, single-cell analysis, single-cell RNA sequencing

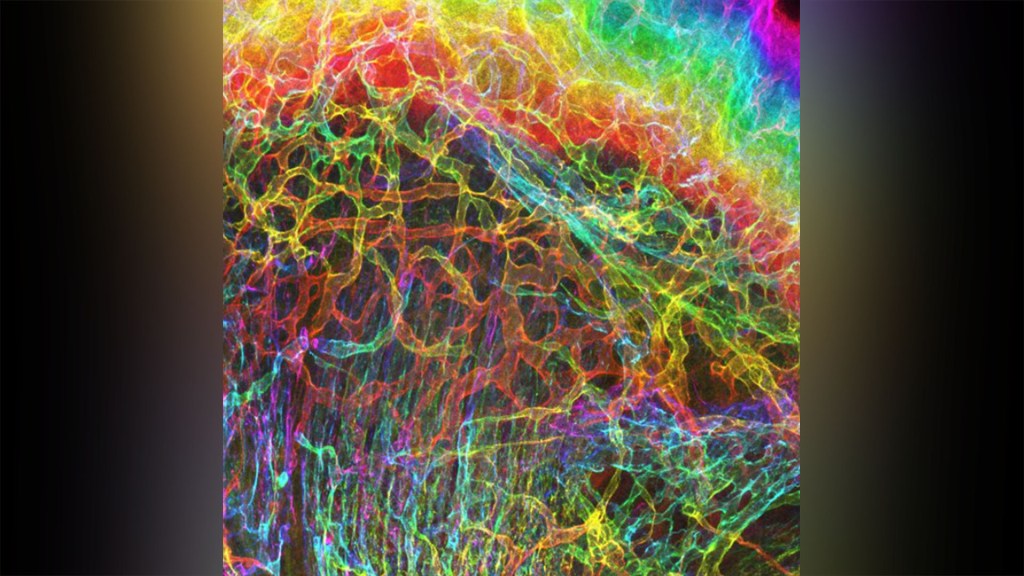

Capturing the Extracellular Matrix in 3D Color

Posted on December 16th, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Sarah Lipp, Purdue University, and Sarah Calve, University of Colorado, Boulder

For experienced and aspiring shutterbugs alike, sometimes the best photo in the bunch turns out to be a practice shot. That’s also occasionally true in the lab when imaging cells and tissues, and it’s the story behind this spectacular image showing the interface of skin and muscle during mammalian development.

Here you see an area of the mouse forelimb located near a bone called the humerus. This particular sample was labeled for laminin, a protein found in the extracellular matrix (ECM) that undergirds cells and tissues to give them mechanical and biochemical support. Computer algorithms were used to convert the original 2D confocal scan into a 3D image, and colorization was added to bring the different layers of tissue into sharper relief.

Skin tissue (bright red and yellow) is located near the top of the image; blood vessels (paler red, orange, and yellow) are in the middle and branching downward; and muscle (green, blue, and purple) makes up the bottom layer.

The image was created by Sarah Lipp, a graduate student in the NIH-supported tissue engineering lab of Sarah Calve. The team focuses on tissue interfaces to better understand the ECM and help devise strategies to engineer musculoskeletal tissues, such as tendon and cartilage.

In February 2020, Lipp was playing around with some new software tools for tissue imaging. Before zeroing in on her main target—the mouse’s myotendinous junction, where muscle transfers its force to tendon, Lipp snapped this practice shot of skin meeting muscle. After processing the practice shot with a color-projecting macro in an image processing tool called Fiji, she immediately liked what she saw.

So, Lipp tweaked the color a bit more and entered the image in the 2020 BioArt Scientific Image & Video Competition, sponsored by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, Bethesda, MD. Last December, the grad student received the good news that her practice shot had snagged one of the prestigious contest’s top awards.

But she’s not stopping there. Lipp is continuing to pursue her research interests at the University of Colorado, Boulder, where the Calve lab recently moved from Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN. Here’s wishing her a career filled with more great images—and great science!

Links:

Muscle and Bone Diseases (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/NIH)

Musculoskeletal Extracellular Matrix Laboratory (University of Colorado, Boulder)

BioArt Scientific Image & Video Competition (Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, Bethesda, MD)

NIH Support: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

Posted In: Snapshots of Life

Tags: BioArt, developmental neurobiology, ECM, extracellular matrix, FASEB Bioart 2020, Fiji, humerus, imaging, laminin, mouse, muscle, myotendinous junction, skin, tendon, tissue engineering

A Race-Free Approach to Diagnosing Chronic Kidney Disease

Posted on October 21st, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: True Touch Lifestyle; crystal light/Shutterstock

Race has a long and tortured history in America. Though great strides have been made through the work of leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to build an equal and just society for all, we still have more work to do, as race continues to factor into American life where it shouldn’t. A medical case in point is a common diagnostic tool for chronic kidney disease (CKD), a condition that affects one in seven American adults and causes a gradual weakening of the kidneys that, for some, will lead to renal failure.

The diagnostic tool is a medical algorithm called estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). It involves getting a blood test that measures how well the kidneys filter out a common waste product from the blood and adding in other personal factors to score how well a person’s kidneys are working. Among those factors is whether a person is Black. However, race is a complicated construct that incorporates components that go well beyond biological and genetic factors to social and cultural issues. The concern is that by lumping together Black people, the algorithm lacks diagnostic precision for individuals and could contribute to racial disparities in healthcare delivery—or even runs the risk of reifying race in a way that suggests more biological significance than it deserves.

That’s why I was pleased recently to see the results of two NIH-supported studies published in The New England Journal of Medicine that suggest a way to take race out of the kidney disease equation [1, 2]. The approach involves a new equation that swaps out one blood test for another and doesn’t ask about race.

For a variety of reasons, including socioeconomic issues and access to healthcare, CKD disproportionately affects the Black community. In fact, Blacks with the condition are also almost four times more likely than whites to develop kidney failure. That’s why Blacks with CKD must visit their doctors regularly to monitor their kidney function, and often that visit involves eGFR.

The blood test used in eGFR measures creatinine, a waste product produced from muscle. For about the past 20 years, a few points have been automatically added to the score of African Americans, based on data showing that adults who identify as Black, on average, have a higher baseline level of circulating creatinine. But adjusting the score upward toward normal function runs the risk of making the kidneys seem a bit healthier than they really are and delaying life-preserving dialysis or getting on a transplant list.

A team led by Chi-yuan Hsu, University of California, San Francisco, took a closer look at the current eGFR calculations. The researchers used long-term data from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study, an NIH-supported prospective, observational study of nearly 4,000 racially and ethnically diverse patients with CKD in the U.S. The study design specified that about 40 percent of its participants should identify as Black.

To look for race-free ways to measure kidney function, the researchers randomly selected more than 1,400 of the study’s participants to undergo a procedure that allows kidney function to be measured directly instead of being estimated based on blood tests. The goal was to develop an accurate approach to estimating GFR, the rate of fluid flow through the kidneys, from blood test results that didn’t rely on race.

Their studies showed that simply omitting race from the equation would underestimate GFR in Black study participants. The best solution, they found, was to calculate eGFR based on cystatin C, a small protein that the kidneys filter from the blood, in place of the standard creatinine. Estimation of GFR using cystatin C generated similarly accurate results but without the need to factor in race.

The second NIH-supported study led by Lesley Inker, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, came to similar conclusions. They set out to develop new equations without race using data from several prior studies. They then compared the accuracy of their new eGFR equations to measured GFR in a validation set of 12 other studies, including about 4,000 participants.

Their findings show that currently used equations that include race, sex, and age overestimated measured GFR in Black Americans. However, taking race out of the equation without other adjustments underestimated measured GFR in Black people. Equations including both creatinine and cystatin C, but omitting race, were more accurate. The new equations also led to smaller estimated differences between Black and non-Black study participants.

The hope is that these findings will build momentum toward widespread adoption of cystatin C for estimating GFR. Already, a national task force has recommended immediate implementation of a new diagnostic equation that eliminates race and called for national efforts to increase the routine and timely measurement of cystatin C [3]. This will require a sea change in the standard measurements of blood chemistries in clinical and hospital labs—where creatinine is routinely measured, but cystatin C is not. As these findings are implemented into routine clinical care, let’s hope they’ll reduce health disparities by leading to more accurate and timely diagnosis, supporting the goals of precision health and encouraging treatment of CKD for all people, regardless of their race.

References:

[1] Race, genetic ancestry, and estimating kidney function in CKD. Hsu CY, Yang W, Parikh RV, Anderson AH, Chen TK, Cohen DL, He J, Mohanty MJ, Lash JP, Mills KT, Muiru AN, Parsa A, Saunders MR, Shafi T, Townsend RR, Waikar SS, Wang J, Wolf M, Tan TC, Feldman HI, Go AS; CRIC Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2021 Sep 23.

[2] New creatinine- and cystatin C-based equations to estimate GFR without race. Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, Tighiouart H, Wang D, Sang Y, Crews DC, Doria A, Estrella MM, Froissart M, Grams ME, Greene T, Grubb A, Gudnason V, Gutiérrez OM, Kalil R, Karger AB, Mauer M, Navis G, Nelson RG, Poggio ED, Rodby R, Rossing P, Rule AD, Selvin E, Seegmiller JC, Shlipak MG, Torres VE, Yang W, Ballew SH,Couture SJ, Powe NR, Levey AS; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. N Engl J Med. 2021 Sep 23.

[3] A unifying approach for GFR estimation: recommendations of the NKF-ASN Task Force on Reassessing the Inclusion of Race in Diagnosing Kidney Disease. Delgado C, Baweja M, Crews DC, Eneanya ND, Gadegbeku CA, Inker LA, Mendu ML, Miller WG, Moxey-Mims MM, Roberts GV, St Peter WL, Warfield C, Powe NR. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021 Sep 22:S0272-6386(21)00828-3.

Links:

Chronic Kidney Disease (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Explaining Your Kidney Test Results: A Tool for Clinical Use (NIDDK)

Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study

Chi-yuan Hsu (University of California, San Francisco)

Lesley Inker (Tufts Medical Center, Boston)

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Posted In: News

Tags: African American health, African Americans, blacks, chronic kidney disease, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study, CKD, creatinine, CRIC Study, cystatin C, diagnostics, eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate, genetics, GFR, glomerular filtration rate, health disparities, kidney dialysis, kidney disease, kidney failure, kidney transplantation, kidneys, muscle, precision health, precision medicine, race, renal failure

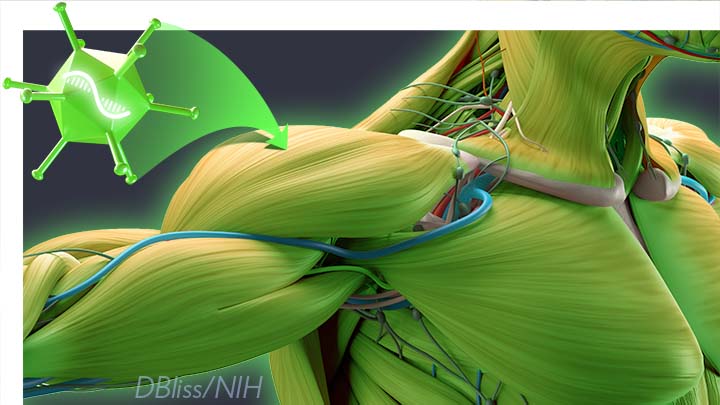

Engineering a Better Way to Deliver Therapeutic Genes to Muscles

Posted on September 21st, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

Amid all the progress toward ending the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s worth remembering that researchers here and around the world continue to make important advances in tackling many other serious health conditions. As an inspiring NIH-supported example, I’d like to share an advance on the use of gene therapy for treating genetic diseases that progressively degenerate muscle, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

As published recently in the journal Cell, researchers have developed a promising approach to deliver therapeutic genes and gene editing tools to muscle more efficiently, thus requiring lower doses [1]. In animal studies, the new approach has targeted muscle far more effectively than existing strategies. It offers an exciting way forward to reduce unwanted side effects from off-target delivery, which has hampered the development of gene therapy for many conditions.

In boys born with DMD (it’s an X-linked disease and therefore affects males), skeletal and heart muscles progressively weaken due to mutations in a gene encoding a critical muscle protein called dystrophin. By age 10, most boys require a wheelchair. Sadly, their life expectancy remains less than 30 years.

The hope is gene therapies will one day treat or even cure DMD and allow people with the disease to live longer, high-quality lives. Unfortunately, the benign adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) traditionally used to deliver the healthy intact dystrophin gene into cells mostly end up in the liver—not in muscles. It’s also the case for gene therapy of many other muscle-wasting genetic diseases.

The heavy dose of viral vector to the liver is not without concern. Recently and tragically, there have been deaths in a high-dose AAV gene therapy trial for X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM), a different disorder of skeletal muscle in which there may already be underlying liver disease, potentially increasing susceptibility to toxicity.

To correct this concerning routing error, researchers led by Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar in the lab of Pardis Sabeti, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, have now assembled an optimized collection of AAVs. They have been refined to be about 10 times better at reaching muscle fibers than those now used in laboratory studies and clinical trials. In fact, researchers call them myotube AAVs, or MyoAAVs.

MyoAAVs can deliver therapeutic genes to muscle at much lower doses—up to 250 times lower than what’s needed with traditional AAVs. While this approach hasn’t yet been tried in people, animal studies show that MyoAAVs also largely avoid the liver, raising the prospect for more effective gene therapies without the risk of liver damage and other serious side effects.

In the Cell paper, the researchers demonstrate how they generated MyoAAVs, starting out with the commonly used AAV9. Their goal was to modify the outer protein shell, or capsid, to create an AAV that would be much better at specifically targeting muscle. To do so, they turned to their capsid engineering platform known as, appropriately enough, DELIVER. It’s short for Directed Evolution of AAV capsids Leveraging In Vivo Expression of transgene RNA.

Here’s how DELIVER works. The researchers generate millions of different AAV capsids by adding random strings of amino acids to the portion of the AAV9 capsid that binds to cells. They inject those modified AAVs into mice and then sequence the RNA from cells in muscle tissue throughout the body. The researchers want to identify AAVs that not only enter muscle cells but that also successfully deliver therapeutic genes into the nucleus to compensate for the damaged version of the gene.

This search delivered not just one AAV—it produced several related ones, all bearing a unique surface structure that enabled them specifically to target muscle cells. Then, in collaboration with Amy Wagers, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, the team tested their MyoAAV toolset in animal studies.

The first cargo, however, wasn’t a gene. It was the gene-editing system CRISPR-Cas9. The team found the MyoAAVs correctly delivered the gene-editing system to muscle cells and also repaired dysfunctional copies of the dystrophin gene better than the CRISPR cargo carried by conventional AAVs. Importantly, the muscles of MyoAAV-treated animals also showed greater strength and function.

Next, the researchers teamed up with Alan Beggs, Boston Children’s Hospital, and found that MyoAAV was effective in treating mouse models of XLMTM. This is the very condition mentioned above, in which very high dose gene therapy with a current AAV vector has led to tragic outcomes. XLMTM mice normally die in 10 weeks. But, after receiving MyoAAV carrying a corrective gene, all six mice had a normal lifespan. By comparison, mice treated in the same way with traditional AAV lived only up to 21 weeks of age. What’s more, the researchers used MyoAAV at a dose 100 times lower than that currently used in clinical trials.

While further study is needed before this approach can be tested in people, MyoAAV was also used to successfully introduce therapeutic genes into human cells in the lab. This suggests that the early success in animals might hold up in people. The approach also has promise for developing AAVs with potential for targeting other organs, thereby possibly providing treatment for a wide range of genetic conditions.

The new findings are the result of a decade of work from Tabebordbar, the study’s first author. His tireless work is also personal. His father has a rare genetic muscle disease that has put him in a wheelchair. With this latest advance, the hope is that the next generation of promising gene therapies might soon make its way to the clinic to help Tabebordbar’s father and so many other people.

Reference:

[1] Directed evolution of a family of AAV capsid variants enabling potent muscle-directed gene delivery across species. Tabebordbar M, Lagerborg KA, Stanton A, King EM, Ye S, Tellez L, Krunnfusz A, Tavakoli S, Widrick JJ, Messemer KA, Troiano EC, Moghadaszadeh B, Peacker BL, Leacock KA, Horwitz N, Beggs AH, Wagers AJ, Sabeti PC. Cell. 2021 Sep 4:S0092-8674(21)01002-3.

Links:

Muscular Dystrophy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

X-linked myotubular myopathy (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (Common Fund/NIH)

Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

Sabeti Lab (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University)

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver N_a_tional Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Common Fund

Posted In: News

Tags: AAV-mediated gene delivery, AAV9, adeno-associated virus, capsid engineering, CRISPR, CRISPR/Cas9, directed evolution, DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, dystrophin, gene editing, gene therapy, gene therapy vector, genetic diseases, genomics, liver, mouse study, muscle, MyoAAV, myotubes, rare diseases, X-linked myotubular myopathy, XLMTM

Boldly Going Where No Science Has Gone Before

Posted on March 26th, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

It was an amazing experience to touch base once again with Kate Rubins, a NASA astronaut aboard the International Space Station. Connecting via live downlink on March 26, 2021, we discussed how space-based research can enable valuable biomedical advances on our planet. For example, over the past five years, NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences has funded a series of tissue chip payloads that have launched to the orbiting laboratory. Rubins, who is a biologist and infectious disease expert, has facilitated three of these projects: Cardinal Heart from Stanford University, Electrical Stimulation of Human Myocytes in Microgravity from the University of Florida, and Cartilage-Bone-Synovium from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Posted In: Director's Album, Director's Album - Photos

Tags: astronaut, bones, cartilage, gravity, heart, International Space Station, Kate Rubins, microgravity, muscle, NASA, space, synovial fluid, tissue chips

The People’s Picks for Best Posts

Posted on January 5th, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s 2021—Happy New Year! Time sure flies in the blogosphere. It seems like just yesterday that I started the NIH Director’s Blog to highlight recent advances in biology and medicine, many supported by NIH. Yet it turns out that more than eight years have passed since this blog got rolling and we are fast approaching my 1,000th post!

I’m pleased that millions of you have clicked on these posts to check out some very cool science and learn more about NIH and its mission. Thanks to the wonders of social media software, we’ve been able to tally up those views to determine each year’s most-popular post. So, I thought it would be fun to ring in the New Year by looking back at a few of your favorites, sort of a geeky version of a top 10 countdown or the People’s Choice Awards. It was interesting to see what topics generated the greatest interest. Spoiler alert: diet and exercise seemed to matter a lot! So, without further ado, I present the winners:

2013: Fighting Obesity: New Hopes from Brown Fat. Brown fat, one of several types of fat made by our bodies, was long thought to produce body heat rather than store energy. But Shingo Kajimura and his team at the University of California, San Francisco, showed in a study published in the journal Nature, that brown fat does more than that. They discovered a gene that acts as a molecular switch to produce brown fat, then linked mutations in this gene to obesity in humans.

What was also nice about this blog post is that it appeared just after Kajimura had started his own lab. In fact, this was one of the lab’s first publications. One of my goals when starting the blog was to feature young researchers, and this work certainly deserved the attention it got from blog readers. Since highlighting this work, research on brown fat has continued to progress, with new evidence in humans suggesting that brown fat is an effective target to improve glucose homeostasis.

2014: In Memory of Sam Berns. I wrote this blog post as a tribute to someone who will always be very near and dear to me. Sam Berns was born with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, one of the rarest of rare diseases. After receiving the sad news that this brave young man had passed away, I wrote: “Sam may have only lived 17 years, but in his short life he taught the rest of us a lot about how to live.”

Affecting approximately 400 people worldwide, progeria causes premature aging. Without treatment, children with progeria, who have completely normal intellectual development, die of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, on average in their early teens.

From interactions with Sam and his parents in the early 2000s, I started to study progeria in my NIH lab, eventually identifying the gene responsible for the disorder. My group and others have learned a lot since then. So, it was heartening last November when the Food and Drug Administration approved the first treatment for progeria. It’s an oral medication called Zokinvy (lonafarnib) that helps prevent the buildup of defective protein that has deadly consequences. In clinical trials, the drug increased the average survival time of those with progeria by more than two years. It’s a good beginning, but we have much more work to do in the memory of Sam and to help others with progeria. Watch for more about new developments in applying gene editing to progeria in the next few days.

2015: Cytotoxic T Cells on Patrol. Readers absolutely loved this post. When the American Society of Cell Biology held its first annual video competition, called CellDance, my blog featured some of the winners. Among them was this captivating video from Alex Ritter, then working with cell biologist Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz of NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The video stars a roving, specialized component of our immune system called cytotoxic T cells. Their job is to seek out and destroy any foreign or detrimental cells. Here, these T cells literally convince a problem cell to commit suicide, a process that takes about 10 minutes from detection to death.

These cytotoxic T cells are critical players in cancer immunotherapy, in which a patient’s own immune system is enlisted to control and, in some cases, even cure the cancer. Cancer immunotherapy remains a promising area of research that continues to progress, with a lot of attention now being focused on developing immunotherapies for common, solid tumors like breast cancer. Ritter is currently completing a postdoctoral fellowship in the laboratory of Ira Mellman, Genentech, South San Francisco. His focus has shifted to how cancer cells protect themselves from T cells. And video buffs—get this—Ritter says he’s now created even cooler videos that than the one in this post.

2016: Exercise Releases Brain-Healthy Protein. The research literature is pretty clear: exercise is good for the brain. In this very popular post, researchers led by Hyo Youl Moon and Henriette van Praag of NIH’s National Institute on Aging identified a protein secreted by skeletal muscle cells to help explore the muscle-brain connection. In a study in Cell Metabolism, Moon and his team showed that this protein called cathepsin B makes its way into the brain and after a good workout influences the development of new neural connections. This post is also memorable to me for the photo collage that accompanied the original post. Why? If you look closely at the bottom right, you’ll see me exercising—part of my regular morning routine!

2017: Muscle Enzyme Explains Weight Gain in Middle Age. The struggle to maintain a healthy weight is a lifelong challenge for many of us. While several risk factors for weight gain, such as counting calories, are within our control, there’s a major one that isn’t: age. Jay Chung, a researcher with NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and his team discovered that the normal aging process causes levels of an enzyme called DNA-PK to rise in animals as they approach middle age. While the enzyme is known for its role in DNA repair, their studies showed it also slows down metabolism, making it more difficult to burn fat.

Since publishing this paper in Cell Metabolism, Chung has been busy trying to understand how aging increases the activity of DNA-PK and its ability to suppress renewal of the cell’s energy-producing mitochondria. Without renewal of damaged mitochondria, excess oxidants accumulate in cells that then activate DNA-PK, which contributed to the damage in the first place. Chung calls it a “vicious cycle” of aging and one that we’ll be learning more about in the future.

2018: Has an Alternative to Table Sugar Contributed to the C. Diff. Epidemic? This impressive bit of microbial detective work had blog readers clicking and commenting for several weeks. So, it’s no surprise that it was the runaway People’s Choice of 2018.

Clostridium difficile (C. diff) is a common bacterium that lives harmlessly in the gut of most people. But taking antibiotics can upset the normal balance of healthy gut microbes, allowing C. diff. to multiply and produce toxins that cause inflammation and diarrhea.

In the 2000s, C. diff. infections became far more serious and common in American hospitals, and Robert Britton, a researcher at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wanted to know why. He and his team discovered that two subtypes of C. diff have adapted to feed on the sugar trehalose, which was approved as a food additive in the United States during the early 2000s. The team’s findings, published in the journal Nature, suggested that hospitals and nursing homes battling C. diff. outbreaks may want to take a closer look at the effect of trehalose in the diet of their patients.

2019: Study Finds No Benefit for Dietary Supplements. This post that was another one that sparked a firestorm of comments from readers. A team of NIH-supported researchers, led by Fang Fang Zhang, Tufts University, Boston, found that people who reported taking dietary supplements had about the same risk of dying as those who got their nutrients through food. What’s more, the mortality benefits associated with adequate intake of vitamin A, vitamin K, magnesium, zinc, and copper were limited to amounts that are available from food consumption. The researchers based their conclusion on an analysis of the well-known National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 1999-2000 and 2009-2010 survey data. The team, which reported its data in the Annals of Internal Medicine, also uncovered some evidence suggesting that certain supplements might even be harmful to health when taken in excess.

2020: Genes, Blood Type Tied to Risk of Severe COVID-19. Typically, my blog focuses on research involving many different diseases. That changed in 2020 due to the emergence of a formidable public health challenge: the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Since last March, the blog has featured 85 posts on COVID-19, covering all aspects of the research response and attracting more visitors than ever. And which post got the most views? It was one that highlighted a study, published last June in the New England Journal of Medicine, that suggested the clues to people’s variable responses to COVID-19 may be found in our genes and our blood types.

The researchers found that gene variants in two regions of the human genome are associated with severe COVID-19 and correspondingly carry a greater risk of COVID-19-related death. The two stretches of DNA implicated as harboring risks for severe COVID-19 are known to carry some intriguing genes, including one that determines blood type and others that play various roles in the immune system.

In fact, the findings suggest that people with blood type A face a 50 percent greater risk of needing oxygen support or a ventilator should they become infected with the novel coronavirus. In contrast, people with blood type O appear to have about a 50 percent reduced risk of severe COVID-19.

That’s it for the blog’s year-by-year Top Hits. But wait! I’d also like to give shout outs to the People’s Choice winners in two other important categories—history and cool science images.

Top History Post: HeLa Cells: A New Chapter in An Enduring Story. Published in August 2013, this post remains one of the blog’s greatest hits with readers. The post highlights science’s use of cancer cells taken in the 1950s from a young Black woman named Henrietta Lacks. These “HeLa” cells had an amazing property not seen before: they could be grown continuously in laboratory conditions. The “new chapter” featured in this post is an agreement with the Lacks family that gives researchers access to the HeLa genome data, while still protecting the family’s privacy and recognizing their enormous contribution to medical research. And the acknowledgments rightfully keep coming from those who know this remarkable story, which has been chronicled in both book and film. Recently, the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives passed the Henrietta Lacks Enhancing Cancer Research Act to honor her extraordinary life and examine access to government-funded cancer clinical trials for traditionally underrepresented groups.

Top Snapshots of Life: A Close-up of COVID-19 in Lung Cells. My blog posts come in several categories. One that you may have noticed is “Snapshots of Life,” which provides a showcase for cool images that appear in scientific journals and often dominate Science as Art contests. My blog has published dozens of these eye-catching images, representing a broad spectrum of the biomedical sciences. But the blog People’s Choice goes to a very recent addition that reveals exactly what happens to cells in the human airway when they are infected with the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19. This vivid image, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, comes from the lab of pediatric pulmonologist Camille Ehre, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This image squeezed in just ahead of another highly popular post from Steve Ramirez, Boston University, in 2019 that showed “What a Memory Looks Like.”

As we look ahead to 2021, I want to thank each of my blog’s readers for your views and comments over the last eight years. I love to hear from you, so keep on clicking! I’m confident that 2021 will generate a lot more amazing and bloggable science, including even more progress toward ending the COVID-19 pandemic that made our past year so very challenging.

Posted In: Generic

Tags: aging, blood type, brown fat, C. diff, cancer, cancer immunotherapy, cathepsin, cathepsin B, Clostridium difficile, coronavirus, COVID-19, cytotoxic T cells, diet, dietary supplements, DNA-PK, exercise, FDA, genes, HeLa cells, Henrietta Lacks, Henrietta Lacks Enhancing Cancer Research Act, Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, Ira Mellman, Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz, lonafarnib, lung cells, memory, mitochondria, muscle, obesity, progeria, sam berns, T cells, trehalose, weight gain, Zokinvy

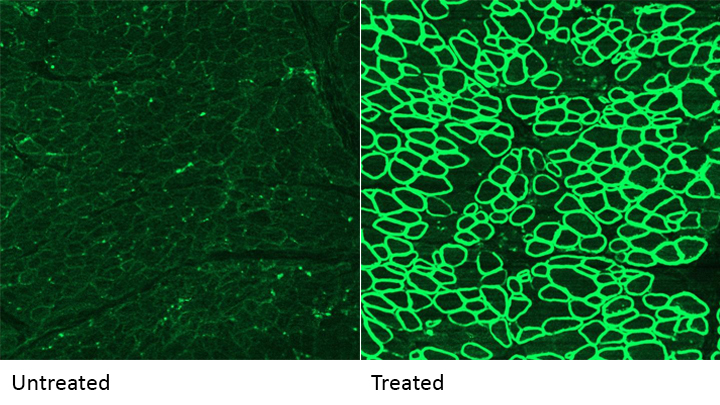

More Progress Toward Gene Editing for Kids with Muscular Dystrophy

Posted on February 26th, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Muscles of untreated mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (left) compared to muscles of similar mice one year after gene-editing treatment (right). Dystrophin production (green) is restored in treated animals, despite therapy-related immune response to the Cas9 editing enzyme (dark spots in white inset). Credit: Charles Gersbach, Duke University, Durham, NC

Thanks to CRISPR and other gene editing technologies, hopes have never been greater for treating or even curing Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and many other rare, genetic diseases that once seemed tragically out of reach. The latest encouraging news comes from a study in which a single infusion of a CRISPR editing system produced lasting benefits in a mouse model of DMD.

There currently is no way to cure DMD, an ultimately fatal disease that mainly affects boys. Caused by mutations in a gene that codes for a critical protein called dystrophin, DMD progressively weakens the skeletal and heart muscles. People with DMD are usually in wheelchairs by the age of 10, with most dying before the age of 30.

The exquisite targeting ability of CRISPR/Cas9 editing systems rely on a sequence-specific guide RNA to direct a scissor-like, bacterial enzyme (Cas9) to just the right spot in the genome, where it can be used to cut out, replace, or repair disease-causing mutations. In previous studies in mice and dogs, researchers directly infused CRISPR systems directly into the animals bodies. This “_in vivo_” approach to gene editing successfully restored production of functional dystrophin proteins, strengthening animals’ muscles within weeks of treatment.

But an important question remained: would CRISPR’s benefits persist over the long term? The answer in a mouse model of DMD appears to be “yes,” according to findings published recently in Nature Medicine by Charles Gersbach, Duke University, Durham, NC, and his colleagues [1]. Specifically, the NIH-funded team found that after mice with DMD received one infusion of a specially designed CRISPR/Cas9 system, the abnormal gene was edited in a way that restored dystrophin production in skeletal and heart muscles for more than a year. What’s more, lasting improvements were seen in the structure of the animals’ muscles throughout the same time period.

As exciting as these results may be, much more research is needed to explore both the safety and the efficacy of in vivo gene editing before it can be tried in humans with DMD. For instance, the researchers found that older mice that received the editing system developed an immune response to the bacterially-derived Cas9 protein. However, this response didn’t prevent the CRISPR/Cas9 system from doing its job or appear to cause any adverse effects. Interestingly, younger animals didn’t show such a response.

It’s worth noting that the immune systems of mice and people often respond quite differently. But the findings do highlight some possible challenges of such treatments, as well as approaches to reduce possible side effects. For instance, the latest findings suggest CRISPR/Cas9 treatment might best be done early in life, before an infant’s immune system is fully developed. Also, if it’s necessary to deliver CRISPR/Cas9 to older individuals, it may be beneficial to suppress the immune system temporarily.

Another concern about CRISPR technology is the potential for damaging, “off-target” edits to other parts of the genome. In the new work, the Duke team found that its CRISPR system made very few “off-target” edits. However, the system did make a surprising number of complex edits to the targeted dystrophin gene, including integration of the viral vector used to deliver Cas9. While those editing “errors” might reduce the efficacy of treatment, researchers said they didn’t appear to affect the health of the mice studied.

It’s important to emphasize that this gene editing research aimed at curing DMD is being done in non-reproductive (somatic) cells, primarily muscle tissue. The NIH does not support the use of gene editing technologies in human embryos or human reproductive (germline) cells, which would change the genetic makeup of future offspring.

As such, the Duke researchers’ CRISPR/Cas9 system is designed to work optimally in a range of muscle and muscle-progenitor cells. Still, they were able to detect editing of the dystrophin-producing gene in the liver, kidney, brain, and other tissues. Importantly, there was no evidence of edits in the germline cells of the mice. The researchers note that their CRISPR system can be reconfigured to limit gene editing to mature muscle cells, although that may reduce the treatment’s efficacy.

It’s truly encouraging to see that CRISPR gene editing may confer lasting benefits in an animal model of DMD, but a great many questions remain before trying this new approach in kids with DMD. But that time is coming—so let’s boldly go forth and get answers to those questions on behalf of all who are affected by this heartbreaking disease.

Reference:

[1] Long-term evaluation of AAV-CRISPR genome editing for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nelson CE, Wu Y, Gemberling MP, Oliver ML, Waller MA, Bohning JD, Robinson-Hamm JN, Bulaklak K, Castellanos Rivera RM, Collier JH, Asokan A, Gersbach CA. Nat Med. 2019 Feb 18.

Links:

Muscular Dystrophy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Gersbach Lab (Duke University, Durham, NC)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (Common Fund/NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

Posted In: News

Tags: children, CRISPR, CRISPR/Cas9, DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, dystrophin, gene editing, genetic diseases, in vivo gene editing, muscle, muscle wasting, muscular dystrophy, rare disease, Somatic Cell Genome Editing, somatic cells

‘Exercise Hormone’ Tied to Bone-Strengthening Benefits

Posted on December 18th, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: gettyimages/kali9

There’s no doubt that exercise is good for us—strengthening our muscles, helping us maintain a healthy weight, maybe even boosting our moods and memories. There’s also been intriguing evidence that exercise may help build strong bones.

Now, an NIH-funded study is shedding light on the mechanism behind exercise’s bone-strengthening benefits [1]. The new work—which may lead to new approaches for treating osteoporosis, a disease that increases the risk of bone fracture—centers on a hormone called irisin that is secreted by muscles during exercise.

In a series of mouse experiments, the researchers found that irisin works directly on a common type of bone cell, stimulating the cells to produce a protein that encourages bones to thin. However, this chain of molecular events ultimately takes a turn for the better and reverses bone loss.

Bruce Spiegelman’s lab at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard University Medical School, Boston, first discovered the irisin hormone in 2012 [2]. In the years since, evidence has accumulated suggesting a connection between irisin and many of the benefits that come with regular workouts. For example, delivering low doses of irisin—sometimes called “the exercise hormone”—increase bone density and strength in mice.

But how does irisin act on bones? The answer hasn’t been at all clear. A major reason is the protein receptor on our cells that binds and responds to irisin wasn’t known.

In the new study reported in the journal Cell, Spiegelman’s team has now identified irisin’s protein receptor, called αVβ5 integrin. Those receptors are present on the surface of osteocytes, the most common cell type found in mature bone tissue.

The researchers went on to show that irisin helps osteocytes to live longer. It also leads the bone cells to begin secreting a protein called sclerostin, known for its role in preparing bones for remodeling and rebuilding by first breaking them down. Interestingly, previous studies also showed sclerostin levels increase in response to the mechanical stresses that come with exercise.

To further explore the role of irisin in mouse studies, the researchers gave the animals the hormone for six days. And indeed, after the treatment, the animals showed higher levels of sclerostin in their blood.

The findings suggest that irisin could form the basis of a new treatment for osteoporosis, a condition responsible for almost nine million fractures around the world each year. While it might seem strange that a treatment intended to strengthen bone would first encourage them to break down, this may be similar to the steps you have to follow when fixing up a house that has weakened timbers. And Spiegelman notes that there’s precedent for such a phenomenon in bone remodeling—treatment for osteoporosis, parathyroid hormone, also works by thinning bones before they are rebuilt.

That said, it’s not yet clear how best to target irisin for strengthening bone. In fact, locking in on the target could be a little complicated. The Speigelman lab found, for example, that mice prone to osteoporosis following the removal of their ovaries were paradoxically protected from weakening bones by the inability to produce irisin.

This new study fits right in with other promising NIH-funded efforts to explore the benefits of exercise. One that I’m particularly excited about is the Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity Consortium (MoTrPAC), which aims to develop a comprehensive map of the molecular changes that arise with physical activity, leading to a range of benefits for body and mind.

Indeed, the therapeutic potential for irisin doesn’t end with bone. In healthy people, irisin circulates throughout the body. In addition to being produced in muscle, its protein precursor is produced in the heart and brain.

The hormone also has been shown to transform energy-storing white fat into calorie-burning brown fat. In the new study, Spiegelman’s team confirms that this effect on fat also depends on the very same integrin receptors present in bone. So, these new findings will no doubt accelerate additional study in Speigelman’s lab and others to explore the many other benefits of irisin—and of exercise—including its potential to improve our moods, memory, and metabolism.

References:

[1] Irisin Mediates Effects on Bone and Fat via αV Integrin Receptors. Kim H, Wrann CD, Jedrychowski M, Vidoni S, Kitase Y, Nagano K, Zhou C, Chou J, Parkman VA, Novick SJ, Strutzenberg TS, Pascal BD, Le PT, Brooks DJ, Roche AM, Gerber KK, Mattheis L, Chen W, Tu H, Bouxsein ML, Griffin PR, Baron R, Rosen CJ, Bonewald LF, Spiegelman BM. Cell. 2018 Dec 13;175(7):1756-1768.

[2] A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Boström P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, Korde A, Ye L, Lo JC, Rasbach KA, Boström EA, Choi JH, Long JZ, Kajimura S, Zingaretti MC, Vind BF, Tu H, Cinti S, Højlund K, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM. Nature. 2012 Jan 11;481(7382):463-8.

Links:

Posted In: News

Tags: aging, Bone, bone remodeling, exercise, exercise hormone, fat, irisin, memory, metabolism, Molecular Tranducers of Physical Activity Consortium, mood, MoTrPAC, muscle, osteocyte, osteoporosis, sclerostin, thinning bones

Gene Editing in Dogs Boosts Hope for Kids with Muscular Dystrophy

Posted on September 11th, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: A CRISPR/cas9 gene editing-based treatment restored production of dystrophin proteins (green) in the diaphragm muscles of dogs with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Credit: UT Southwestern

CRISPR and other gene editing tools hold great promise for curing a wide range of devastating conditions caused by misspellings in DNA. Among the many looking to gene editing with hope are kids with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an uncommon and tragically fatal genetic disease in which their muscles—including skeletal muscles, the heart, and the main muscle used for breathing—gradually become too weak to function. Such hopes were recently buoyed by a new study that showed infusion of the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system could halt disease progression in a dog model of DMD.

As seen in the micrographs above, NIH-funded researchers were able to use the CRISPR/Cas9 editing system to restore production of a critical protein, called dystrophin, by up to 92 percent in the muscle tissue of affected dogs. While more study is needed before clinical trials could begin in humans, this is very exciting news, especially when one considers that boosting dystrophin levels by as little as 15 percent may be enough to provide significant benefit for kids with DMD.

Posted In: News

Tags: animal models, beagles, Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, CRISPR, CRISPR/Cas9, diaphragm muscle, DMD, dogs, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, dystrophin, gene editing, genetic diseases, heart, muscle, muscular dystrophy, rare diseases, Somatic Cell Genome Editing

Snapshots of Life: Building Muscle in a Dish

Posted on March 29th, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Kevin Murach, Charlotte Peterson, and John McCarthy, University of Kentucky, Lexington

As many of us know from hard experience, tearing a muscle while exercising can be a real pain. The good news is that injured muscle will usually heal quickly for many of us with the help of satellite cells. Never heard of them? They are the adult stem cells in our skeletal muscles long recognized for their capacity to make new muscle fibers called myotubes.

This striking image shows what happens when satellite cells from mice are cultured in a lab dish. With small adjustments to the lab dish’s growth media, those cells fuse to form myotubes. Here, you see the striated myotubes (red) with multiple cell nuclei (blue) characteristic of mature muscle fibers. The researchers also used a virus to genetically engineer some of the muscle to express a fluorescent protein (green).

Tags: aging, exercise, FASEB Bioart 2017, fluorescence microscopy, muscle, muscle fibers, myotubes, satellite cells, senior health, skeletal muscle