musculoskeletal disorder – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

Cool Videos: The Ghost in the Lab Dish?

Posted on October 26th, 2017 by Dr. Francis Collins

As Halloween approaches, lots of kids and kids-at-heart will be watching out for ghosts and goblins. So, to help meet the seasonal demand for scary visuals, I’d like to share this award-winning image that’s been packaged into a brief video.

The “ghoul” you see above is no fleeting apparition: it’s a mouse cell labelled to reveal its microtubules, which are dynamic filaments involved in cellular structure, transport, and motility. Graduate student Victor DeBarros captured this image a couple of years ago in the NIH-supported lab of Randall Duncan at the University of Delaware, Newark, as part of research on the rare skeletal disorder metatropic dysplasia (MD).

Posted In: Health, Science, Video

Tags: art, Bone, cartilage, chondrocytes, Halloween, metatropic dysplasia, microtubules, musculoskeletal disorder, rare disease, skeletal disoder, translational science, TRPV4, University of Delaware Science as Art

Snapshots of Life: Muscling in on Development

Posted on July 27th, 2017 by Dr. Francis Collins

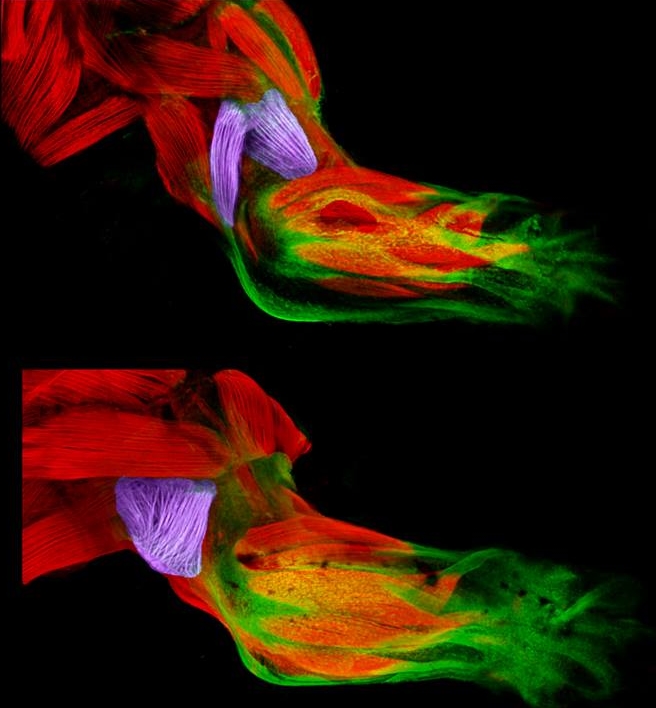

Credit: Mary P. Colasanto, University of Utah, Salt Lake City

Twice a week, I do an hour of weight training to maintain muscle strength and tone. Millions of Americans do the same, and there’s always a lot of attention paid to those upper arm muscles—the biceps and triceps. Less appreciated is another arm muscle that pumps right along during workouts: the brachialis. This muscle—located under the biceps—helps your elbow flex when you are doing all kinds of things, whether curling a 50-pound barbell or just grabbing a bag of groceries or your luggage out of the car.

Now, scientific studies of the triceps and brachialis are providing important clues about how the body’s 40 different types of limb muscles assume their distinct identities during development [1]. In these images from the NIH-supported lab of Gabrielle Kardon at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, you see the developing forelimb of a healthy mouse strain (top) compared to that of a mutant mouse strain with a stiff, abnormal gait (bottom).

Tags: brachialis, connective tissue, development, FluoRender, forelimb muscles, genetics, genomics, lateral triceps, limb muscles, limbs, mouse, mouse genetics, muscle, musculoskeletal disorder, rare disease, Tbx3, transcription factor, triceps, ulnar-mammary syndrome, UMS, University of Utah’s 2016 Research as Art

Scoliosis Traced to Problems in Spinal Fluid Flow

Posted on July 7th, 2016 by Dr. Francis Collins

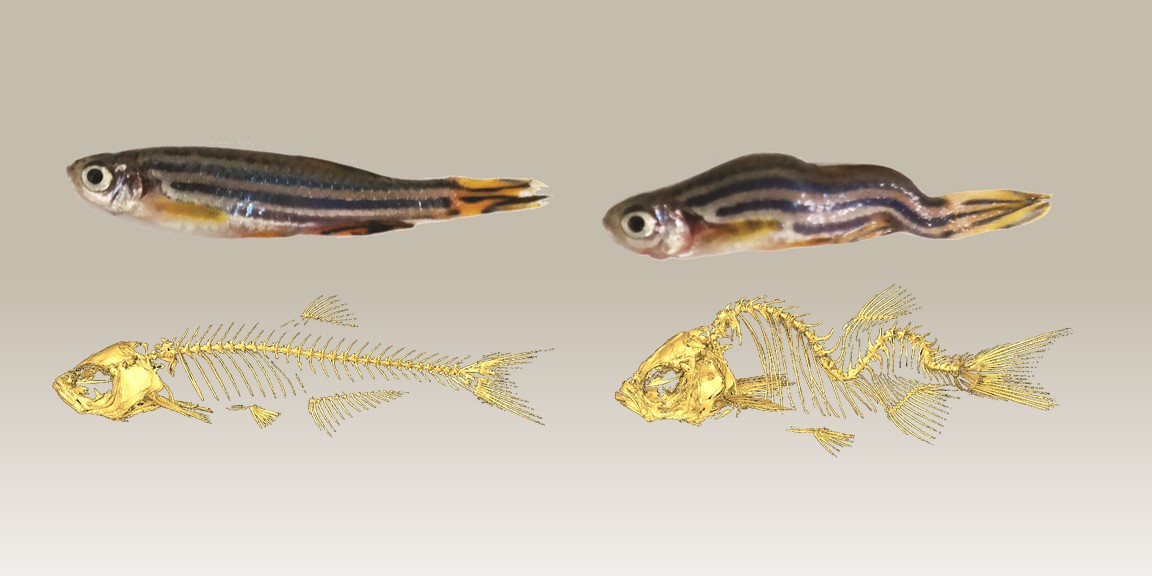

Caption: Normal zebrafish (top left) and a normal skeleton (bottom left); zebrafish with scoliosis (top right) and an abnormal scoliotic skeleton (bottom right).

Credit: Grimes DT, Boswell CW, Morante NF, Henkelman RM.

Many of us may remember undergoing a simple screening test in school to look for abnormal curvatures of the spine. The condition known as adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (IS) affects 3 percent of children, typically showing up in the tween or early teen years when kids are growing rapidly. While scoliosis can occur due to physical defects in bones or muscles, more often the C- or S-shaped spinal curves develop for unknown reasons. Because the basic biological mechanisms of IS have been poorly understood, treatment to prevent further progression and potentially painful disfigurement has been limited to restrictive braces or corrective surgery.

Now, in work involving zebrafish models of IS, a team of NIH-funded researchers and their colleagues report a surprising discovery that suggests it may be possible to develop more precisely targeted therapeutics to reduce or even prevent scoliosis. The team’s experiments have, for the first time, shown that mutation of a gene associated with spinal curvature in both zebrafish and humans has its effect by altering the function of the tiny hair-like projections, known as cilia, that line the spinal cord. Without the cilia’s normal, beating movements, the fluid that bathes the brain and spinal cord doesn’t flow properly, and zebrafish develop abnormal spinal curves that look much like those seen in kids with scoliosis. However, when the researchers used genetic engineering to correct such mutations and thereby restore normal cilia function and flow of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), the zebrafish did not develop spinal curvature.

Tags: adolescence, adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, cerebral spinal fluid, childhood disorder, cilia, CSF, CSF flow, human development, model organisms, musculoskeletal disorder, ptk7 gene, scoliosis, spinal curvature, zebrafish