neuroplasticity – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

How Neurons Make Connections

Posted on August 8th, 2023 by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Credit: Emily Heckman, Doe Lab, University of Oregon, Eugene

For many people, they are tiny pests. These fruit flies that sometimes hover over a bowl of peaches or a bunch of bananas. But for a dedicated community of researchers, fruit flies are an excellent model organism and source of information into how neurons self-organize during the insect’s early development and form a complex, fully functioning nervous system.

That’s the scientific story on display in this beautiful image of a larval fruit fly’s developing nervous system. Its subtext is: fundamental discoveries in the fruit fly, known in textbooks as Drosophila melanogaster, provide basic clues into the development and repair of the human nervous system. That’s because humans and fruit flies, though very distantly related through the millennia, still share many genes involved in their growth and development. In fact, 60 percent of the Drosophila genome is identical to ours.

Once hatched, as shown in this image, a larval fly uses neurons (magenta) to sense its environment. These include neurons that sense the way its body presses against the surrounding terrain, as needed to coordinate the movements of its segmented body parts and crawl in all directions.

This same set of neurons will generate painful sensations, such as the attack of a parasitic wasp. Paintbrush-like neurons in the fly’s developing head (magenta, left side) allow the insect to taste the sweetness of a peach or banana.

There is a second subtype of neurons, known as proprioceptors (green). These neurons will give the young fly its “sixth sense” understanding about where its body is positioned in space. The complete collection of developing neurons shown here are responsible for all the fly’s primary sensations. They also send these messages on to the insect’s central nervous system, which contains thousands of other neurons that are hidden from view.

Emily Heckman, now a postdoctoral researcher at the Michigan Neuroscience Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, captured this image during her graduate work in the lab of Chris Doe, University of Oregon, Eugene. For her keen eye, she received a trainee/early-career BioArt Award from the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB), which each year celebrates the art of science.

The image is one of many from a much larger effort in the Doe lab that explores the way neurons that will partner find each other and link up to drive development. Heckman and Doe also wanted to know how neurons in the developing brain interconnect into integrated neural networks, or circuits, and respond when something goes wrong. To find out, they disrupted sensory neurons or forced them to take alternate paths and watched to see what would happen.

As published in the journal eLife [1], the system has an innate plasticity. Their findings show that developing sensory neurons instruct one another on how to meet up just right. If one suddenly takes an alternate route, its partner can still reach out and make the connection. Once an electrically active neural connection, or synapse, is made, the neural signals themselves slow or stop further growth. This kind of adaptation and crosstalk between neurons takes place only during a particular critical window during development.

Heckman says part of what she enjoys about the image is how it highlights that many sensory neurons develop simultaneously and in a coordinated process. What’s also great about visualizing these events in the fly embryo is that she and other researchers can track many individual neurons from the time they’re budding stem cells to when they become a fully functional and interconnected neural circuit.

So, the next time you see fruit flies hovering in the kitchen, just remember there’s more to their swarm than you think. Our lessons learned studying them will help point researchers toward new ways in people to restore or rebuild neural connections after devastating disruptions from injury or disease.

Reference:

Presynaptic contact and activity opposingly regulate postsynaptic dendrite outgrowth. Heckman EL, Doe CQ. Elife. 2022 Nov 30;11:e82093.

Links:

Research Organisms (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Doe Lab (University of Oregon, Eugene)

Emily Heckman (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor)

BioArt Awards (Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, Rockville, MD)

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Posted In: Snapshots of Life

Tags: 2022 BioArt Awards, development, Drosophila melanogaster, fruit fly, insects, model organisms, nervous system, neural circuits, neurons, neuroplasticity, neuroscience, proprioception, sensory neurons

New Evidence Suggests Aging Brains Continue to Make New Neurons

Posted on April 10th, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

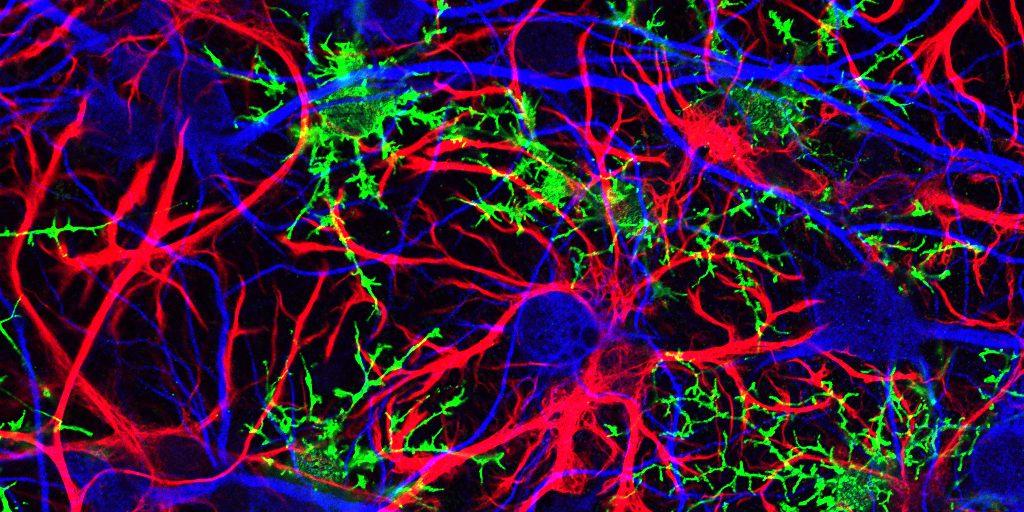

Caption: Mammalian hippocampal tissue. Immunofluorescence microscopy showing neurons (blue) interacting with neural astrocytes (red) and oligodendrocytes (green).

Credit: Jonathan Cohen, Fields Lab, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH

There’s been considerable debate about whether the human brain has the capacity to make new neurons into adulthood. Now, a recently published study offers some compelling new evidence that’s the case. In fact, the latest findings suggest that a healthy person in his or her seventies may have about as many young neurons in a portion of the brain essential for learning and memory as a teenager does.

As reported in the journal Cell Stem Cell, researchers examined the brains of healthy people, aged 14 to 79, and found similar numbers of young neurons throughout adulthood [1]. Those young neurons persisted in older brains that showed other signs of decline, including a reduced ability to produce new blood vessels and form new neural connections. The researchers also found a smaller reserve of quiescent, or inactive, neural stem cells in a brain area known to support cognitive-emotional resilience, the ability to cope with and bounce back from stressful circumstances.

While more study is clearly needed, the findings suggest healthy elderly people may have more cognitive reserve than is commonly believed. However, the findings may also help to explain why even perfectly healthy older people often find it difficult to face new challenges, such as travel or even shopping at a different grocery store, that wouldn’t have fazed them earlier in life.

Posted In: Health, News, Science

Tags: aging, aging brain, angiogenesis, autopsy study, brain, Brain Collection of the New York State Psychiatric Institute at Columbia University, cognition, dentate gyrus, elderly, glial cells, hippocampus, longevity, memory, neural progenitor cells, neural stem cells, neurogenesis, neurology, neurons, neuroplasticity, stereology