optogenetics – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

The Amazing Brain: Seeing Two Memories at Once

Posted on August 2nd, 2022 by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Credit: Stephanie Grella, Boston University, MA

The NIH’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative is revolutionizing our understanding of the human brain. As described in the initiative’s name, the development of innovative imaging technologies will enable researchers to see the brain in new and increasingly dynamic ways. Each year, the initiative celebrates some standout and especially creative examples of such advances in the “Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo & Video Contest. During most of August, I’ll share some of the most eye-catching developments in our blog series, The Amazing Brain.

In this fascinating image, you’re seeing two stored memories, which scientists call engrams, in the hippocampus region of a mouse’s brain. The engrams show the neural intersection of a good memory (green) and a bad memory (pink). You can also see the nuclei of many neurons (blue), including nearby neurons not involved in the memory formation.

This award-winning image was produced by Stephanie Grella in the lab of NIH-supported neuroscientist Steve Ramirez, Boston University, MA. It’s also not the first time that the blog has featured Grella’s technical artistry. Grella, who will soon launch her own lab at Loyola University, Chicago, previously captured what a single memory looks like.

To capture two memories at once, Grella relied on a technology known as optogenetics. This powerful method allows researchers to genetically engineer neurons and selectively activate them in laboratory mice using blue light. In this case, Grella used a harmless virus to label neurons involved in recording a positive experience with a light-sensitive molecule, known as an opsin. Another molecular label was used to make those same cells appear green when activated.

After any new memory is formed, there’s a period of up to about 24 hours during which the memory is malleable. Then, the memory tends to stabilize. But with each retrieval, the memory can be modified as it restabilizes, a process known as memory reconsolidation.

Grella and team decided to try to use memory reconsolidation to their advantage to neutralize an existing fear. To do this, they placed their mice in an environment that had previously startled them. When a mouse was retrieving a fearful memory (pink), the researchers activated with light associated with the positive memory (green), which for these particular mice consisted of positive interactions with other mice. The aim was to override or disrupt the fearful memory.

As shown by the green all throughout the image, the experiment worked. While the mice still showed some traces of the fearful memory (pink), Grella explained that the specific cells that were the focus of her study shifted to the positive memory (green).

What’s perhaps even more telling is that the evidence suggests the mice didn’t just trade one memory for another. Rather, it appears that activating a positive memory actually suppressed or neutralized the animal’s fearful memory. The hope is that this approach might one day inspire methods to help people overcome negative and unwanted memories, such as those that play a role in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health issues.

Links:

Stephanie Grella (Boston University, MA)

Ramirez Group (Boston University)

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Show Us Your BRAINs Photo & Video Contest (BRAIN Initiative)

NIH Support: BRAIN Initiative; Common Fund

Posted In: Snapshots of Life

Tags: brain, brain imaging, BRAIN Initiative, Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies Initiative, engrams, fear, hippocampus, memories, memory, mental health, mental illness, mouse study, neurons, neuroscience, opsin, optogenetics, post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD, Show Us Your BRAINs!

Could A Gut-Brain Connection Help Explain Autism?

Posted on January 23rd, 2020 by Dr. Francis Collins

Diego Bohórquez/Credit: Duke University, Durham, NC

You might think nutrient-sensing cells in the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract would have no connection whatsoever to autism spectrum disorder (ASD). But if Diego Bohórquez’s “big idea” is correct, these GI cells, called neuropods, could one day help to provide a direct link into understanding and treating some aspects of autism and other brain disorders.

Bohórquez, a researcher at Duke University, Durham, NC, recently discovered that cells in the intestine, previously known for their hormone-releasing ability, form extensions similar to neurons. He also found that those extensions connect to nerve fibers in the gut, which relay signals to the vagus nerve and onward to the brain. In fact, he found that those signals reach the brain in milliseconds [1].

Bohórquez has dedicated his lab to studying this direct, high-speed hookup between gut and brain and its impact on nutrient sensing, eating, and other essential behaviors. Now, with support from a 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, he will also explore the potential for treating autism and other brain disorders with drugs that act on the gut.

Bohórquez became interested in autism and its possible link to the gut-brain connection after a chance encounter with Geraldine Dawson, director of the Duke Center for Autism and Brain Development. Dawson mentioned that autism typically affects multiple organ systems.

With further reading, he discovered that kids with autism frequently cope with GI issues, including bowel inflammation, abdominal pain, constipation, and/or diarrhea [2]. They often also show unusual food-related behaviors, such as being extremely picky eaters. But his curiosity was especially piqued by evidence that certain gut microbes can influence abnormal behaviors in mice that model autism.

With his New Innovator Award, Bohórquez will study neuropods and the gut-brain connection in a mouse model of autism. Using the tools of optogenetics, which make it possible to activate cells with light, he’ll also see whether autism-like symptoms in mice can be altered or alleviated by controlling neuropods in the gut. Those symptoms include anxiety, repetitive behaviors, and lack of interest in interacting with other mice. He’ll also explore changes in the animals’ eating habits.

In another line of study, he will take advantage of intestinal tissue samples collected from people with autism. He’ll use those tissues to grow and then examine miniature intestinal “organoids,” looking for possible evidence that those from people with autism are different from others.

For the millions of people now living with autism, no truly effective drug therapies are available to help to manage the condition and its many behavioral and bodily symptoms. Bohórquez hopes one day to change that with drugs that act safely on the gut. In the meantime, he and his fellow “GASTRONAUTS” look forward to making some important and fascinating discoveries in the relatively uncharted territory where the gut meets the brain.

References:

[1] A gut-brain neural circuit for nutrient sensory transduction. Kaelberer MM, Buchanan KL, Klein ME, Barth BB, Montoya MM, Shen X, Bohórquez DV. Science. 2018 Sep 21;361(6408).

[2] Association of maternal report of infant and toddler gastrointestinal symptoms with autism: evidence from a prospective birth cohort. Bresnahan M, Hornig M, Schultz AF, Gunnes N, Hirtz D, Lie KK, Magnus P, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Roth C, Schjølberg S, Stoltenberg C, Surén P, Susser E, Lipkin WI. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 May;72(5):466-474.

Links:

Autism Spectrum Disorder (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

Bohórquez Lab (Duke University, Durham, NC)

Bohórquez Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (Common Fund)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Institute of Mental Health

Posted In: Creative Minds

Tags: 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, autism, Autism Spectrum Disorder, brain, brain development, brain disorders, child development, gastrointestinal tract, GASTRONAUTS, gut, gut microbiome, gut-brain connection, microbiome, neuropods, optogenetics, organoids, vagus nerve, young children

A Real-Time Look at Value-Based Decision Making

Posted on January 16th, 2020 by Dr. Francis Collins

All of us make many decisions every day. For most things, such as which jacket to wear or where to grab a cup of coffee, there’s usually no right answer, so we often decide using values rooted in our past experiences. Now, neuroscientists have identified the part of the mammalian brain that stores information essential to such value-based decision making.

Researchers zeroed in on this particular brain region, known as the retrosplenial cortex (RSC), by analyzing movies—including the clip shown about 32 seconds into this video—that captured in real time what goes on in the brains of mice as they make decisions. Each white circle is a neuron, and the flickers of light reflect their activity: the brighter the light, the more active the neuron at that point in time.

All told, the NIH-funded team, led by Ryoma Hattori and Takaki Komiyama, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, made recordings of more than 45,000 neurons across six regions of the mouse brain [1]. Neural activity isn’t usually visible. But, in this case, researchers used mice that had been genetically engineered so that their neurons, when activated, expressed a protein that glowed.

Their system was also set up to encourage the mice to make value-based decisions, including choosing between two drinking tubes, each with a different probability of delivering water. During this decision-making process, the RSC proved to be the region of the brain where neurons persistently lit up, reflecting how the mouse evaluated one option over the other.

The new discovery, described in the journal Cell, comes as something of a surprise to neuroscientists because the RSC hadn’t previously been implicated in value-based decisions. To gather additional evidence, the researchers turned to optogenetics, a technique that enabled them to use light to inactivate neurons in the RSC’s of living animals. These studies confirmed that, with the RSC turned off, the mice couldn’t retrieve value information based on past experience.

The researchers note that the RSC is heavily interconnected with other key brain regions, including those involved in learning, memory, and controlling movement. This indicates that the RSC may be well situated to serve as a hub for storing value information, allowing it to be accessed and acted upon when it is needed.

The findings are yet another amazing example of how advances coming out of the NIH-led Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative are revolutionizing our understanding of the brain. In the future, the team hopes to learn more about how the RSC stores this information and sends it to other parts of the brain. They note that it will also be important to explore how activity in this brain area may be altered in schizophrenia, dementia, substance abuse, and other conditions that may affect decision-making abilities. It will also be interesting to see how this develops during childhood and adolescence.

Reference:

[1] Area-Specificity and Plasticity of History-Dependent Value Coding During Learning. Hattori R, Danskin B, Babic Z, Mlynaryk N, Komiyama T. Cell. 2019 Jun 13;177(7):1858-1872.e15.

Links:

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Komiyama Lab (UCSD, La Jolla)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Eye Institute; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

Posted In: Cool Videos

Tags: brain, BRAIN Initiative, connectomics, decision making, dementia, learning, mammalian brain, memory, neurology, neurons, neuroscience, optogenetics, retrosplenial cortex, schizophrenia, substance abuse, value-based decision making

What a Memory Looks Like

Posted on November 21st, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Stephanie Grella, Ramirez Group, Boston University

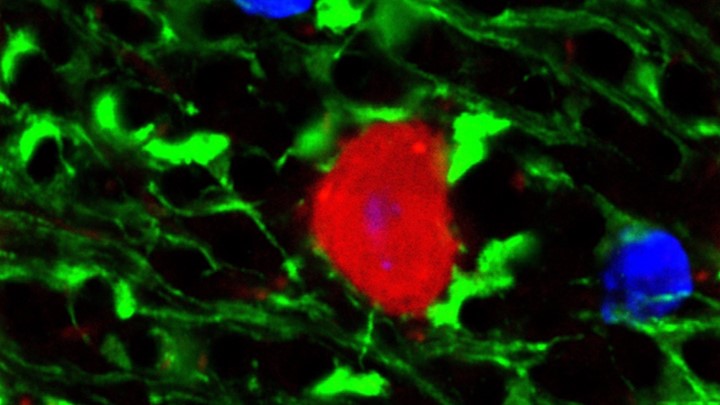

Your brain has the capacity to store a lifetime of memories, covering everything from the name of your first pet to your latest computer password. But what does a memory actually look like? Thanks to some very cool neuroscience, you are looking at one.

The physical manifestation of a memory, or engram, consists of clusters of brain cells active when a specific memory was formed. Your brain’s hippocampus plays an important role in storing and retrieving these memories. In this cross-section of a mouse hippocampus, imaged by the lab of NIH-supported neuroscientist Steve Ramirez, at Boston University, cells belonging to an engram are green, while blue indicates those not involved in forming the memory.

When a memory is recalled, the cells within an engram reactivate and turn on, to varying degrees, other neural circuits (e.g., sight, sound, smell, emotions) that were active when that memory was recorded. It’s not clear how these brain-wide connections are made. But it appears that engrams are the gatekeepers that mediate memory.

The story of this research dates back several years, when Ramirez helped develop a system that made it possible to image engrams by tagging cells in the mouse brain with fluorescent dyes. Using an innovative technology developed by other researchers, called optogenetics, Ramirez’s team then discovered it could shine light onto a collection of hippocampal neurons storing a specific memory and reactivate the sensation associated with the memory [1].

Ramirez has since gone on to show that, at least in mice, optogenetics can be used to trick the brain into creating a false memory [2]. From this work, he has also come to the interesting and somewhat troubling conclusion that the most accurate memories appear to be the ones that are never recalled. The reason: the mammalian brain edits—and slightly changes—memories whenever they are accessed.

All of the above suggested to Ramirez that, given its tremendous plasticity, the brain may possess the power to downplay a traumatic memory or to boost a pleasant recollection. Toward that end, Ramirez’s team is now using its mouse system to explore ways of suppressing one engram while enhancing another [3].

For Ramirez, though, the ultimate goal is to develop brain-wide maps that chart all of the neural networks involved in recording, storing, and retrieving memories. He recently was awarded an NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award to begin the process. Such maps will be invaluable in determining how stress affects memory, as well as what goes wrong in dementia and other devastating memory disorders.

References:

[1] Optogenetic stimulation of a hippocampal engram activates fear memory recall. Liu X, Ramirez S, Pang PT, Puryear CB, Govindarajan A, Deisseroth K, Tonegawa S. Nature. 2012 Mar 22;484(7394):381-385.

[2] Creating a false memory in the hippocampus. Ramirez S, Liu X, Lin PA, Suh J, Pignatelli M, Redondo RL, Ryan TJ, Tonegawa S. Science. 2013 Jul 26;341(6144):387-391.

[3] Artificially Enhancing and Suppressing Hippocampus-Mediated Memories. Chen BK, Murawski NJ, Cincotta C, McKissick O, Finkelstein A, Hamidi AB, Merfeld E, Doucette E, Grella SL, Shpokayte M, Zaki Y, Fortin A, Ramirez S. Curr Biol. 2019 Jun 3;29(11):1885-1894.

Links:

The Ramirez Group (Boston University, MA)

Ramirez Project Information (Common Fund/NIH)

NIH Director’s Early Independence Award (Common Fund)

NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award (Common Fund)

NIH Support: Common Fund

Posted In: Snapshots of Life

Tags: bad memory, brain, dementia, engrams, false memory, hippocampus, memory, memory disordes, neuroscience, NIH Director's Early Independence Award, NIH Director's Transformative Research Award, optogenetics

The Amazing Brain: Making Up for Lost Vision

Posted on August 27th, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

Recently, I’ve highlighted just a few of the many amazing advances coming out of the NIH-led Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative. And for our grand finale, I’d like to share a cool video that reveals how this revolutionary effort to map the human brain is opening up potential plans to help people with disabilities, such as vision loss, that were once unimaginable.

This video, produced by Jordi Chanovas and narrated by Stephen Macknik, State University of New York Downstate Health Sciences University, Brooklyn, outlines a new strategy aimed at restoring loss of central vision in people with age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of vision loss among people age 50 and older. The researchers’ ultimate goal is to give such people the ability to see the faces of their loved ones or possibly even read again.

In the innovative approach you see here, neuroscientists aren’t even trying to repair the part of the eye destroyed by AMD: the light-sensitive retina. Instead, they are attempting to recreate the light-recording function of the retina within the brain itself.

How is that possible? Normally, the retina streams visual information continuously to the brain’s primary visual cortex, which receives the information and processes it into the vision that allows you to read these words. In folks with AMD-related vision loss, even though many cells in the center of the retina have stopped streaming, the primary visual cortex remains fully functional to receive and process visual information.

About five years ago, Macknik and his collaborator Susana Martinez-Conde, also at Downstate, wondered whether it might be possible to circumvent the eyes and stream an alternative source of visual information to the brain’s primary visual cortex, thereby restoring vision in people with AMD. They sketched out some possibilities and settled on an innovative system that they call OBServ.

Among the vital components of this experimental system are tiny, implantable neuro-prosthetic recording devices. Created in the Macknik and Martinez-Conde labs, this 1-centimeter device is powered by induction coils similar to those in the cochlear implants used to help people with profound hearing loss. The researchers propose to surgically implant two of these devices in the rear of the brain, where they will orchestrate the visual process.

For technical reasons, the restoration of central vision will likely be partial, with the window of vision spanning only about the size of one-third of an adult thumbnail held at arm’s length. But researchers think that would be enough central vision for people with AMD to regain some of their lost independence.

As demonstrated in this video from the BRAIN Initiative’s “Show Us Your Brain!” contest, here’s how researchers envision the system would ultimately work:

• A person with vision loss puts on a specially designed set of glasses. Each lens contains two cameras: one to record visual information in the person’s field of vision; the other to track that person’s eye movements enabled by residual peripheral vision.

• The eyeglass cameras wirelessly stream the visual information they have recorded to two neuro-prosthetic devices implanted in the rear of the brain.

• The neuro-prosthetic devices process and project this information onto a specific set of excitatory neurons in the brain’s hard-wired visual pathway. Researchers have previously used genetic engineering to turn these neurons into surrogate photoreceptor cells, which function much like those in the eye’s retina.

• The surrogate photoreceptor cells in the brain relay visual information to the primary visual cortex for processing.

• All the while, the neuro-prosthetic devices perform quality control of the visual signals, calibrating them to optimize their contrast and clarity.

While this might sound like the stuff of science-fiction (and this actual application still lies several years in the future), the OBServ project is now actually conceivable thanks to decades of advances in the fields of neuroscience, vision, bioengineering, and bioinformatics research. All this hard work has made the primary visual cortex, with its switchboard-like wiring system, among the brain’s best-understood regions.

OBServ also has implications that extend far beyond vision loss. This project provides hope that once other parts of the brain are fully mapped, it may be possible to design equally innovative systems to help make life easier for people with other disabilities and conditions.

Links:

Age-Related Macular Degeneration (National Eye Institute/NIH)

Macknik Lab (SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University, Brooklyn)

Martinez-Conde Laboratory (SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University)

Show Us Your Brain! (BRAIN Initiative/NIH)

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

NIH Support: BRAIN Initiative

Posted In: Cool Videos

Tags: aging, AMD, blindness, brain, BRAIN Initiative, central vision, cochlear implants, eyeglass camera, gene therapy, neuro-prosthetic, neuroscience, OBServe, optogenetics, photoreceptor cells, phototransduction, primary visual cortex, retina, Show Us Your Brain, vision, vision loss

‘Nanoantennae’ Make Infrared Vision Possible

Posted on March 5th, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

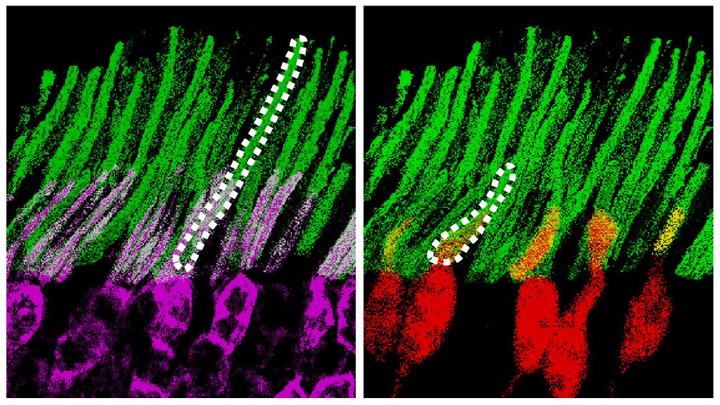

Caption: Nanoparticles (green) bind to light-sensing rod (violet) and cone (red) cells in the mouse retina. Dashed lines (white) highlight cells’ inner/outer segments.

Credit: Ma et al. Cell, 2019

Infrared vision often brings to mind night-vision goggles that allow soldiers to see in the dark, like you might have seen in the movie Zero Dark Thirty. But those bulky goggles may not be needed one day to scope out enemy territory or just the usual things that go bump in the night. In a dramatic advance that brings together material science and the mammalian vision system, researchers have just shown that specialized lab-made nanoparticles applied to the retina, the thin tissue lining the back of the eye, can extend natural vision to see in infrared light.

The researchers showed in mouse studies that their specially crafted nanoparticles bind to the retina’s light-sensing cells, where they act like “nanoantennae” for the animals to see and recognize shapes in infrared—day or night—for at least 10 weeks. Even better, the mice maintained their normal vision the whole time and showed no adverse health effects. In fact, some of the mice are still alive and well in the lab, although their ability to see in infrared may have worn off.

When light enters the eyes of mice, humans, or any mammal, light-sensing cells in the retina absorb wavelengths within the range of visible light. (That’s roughly from 400 to 700 nanometers.) While visible light includes all the colors of the rainbow, it actually accounts for only a fraction of the full electromagnetic spectrum. Left out are the longer wavelengths of infrared light. That makes infrared light invisible to the naked eye.

In the study reported in the journal Cell, an international research team including Gang Han, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, wanted to find a way for mammalian light-sensing cells to absorb and respond to the longer wavelengths of infrared [1]. It turns out Han’s team had just the thing to do it.

His NIH-funded team was already working on the nanoparticles now under study for application in a field called optogenetics—the use of light to control living brain cells [2]. Optogenetics normally involves the stimulation of genetically modified brain cells with blue light. The trouble is that blue light doesn’t penetrate brain tissue well.

That’s where Han’s so-called upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) came in. They attempt to get around the normal limitations of optogenetic tools by incorporating certain rare earth metals. Those metals have a natural ability to absorb lower energy infrared light and convert it into higher energy visible light (hence the term upconversion).

But could those UCNPs also serve as miniature antennae in the eye, receiving infrared light and emitting readily detected visible light? To find out in mouse studies, the researchers injected a dilute solution containing UCNPs into the back of eye. Such sub-retinal injections are used routinely by ophthalmologists to treat people with various eye problems.

These UCNPs were modified with a protein that allowed them to stick to light-sensing cells. Because of the way that UCNPs absorb and emit wavelengths of light energy, they should to stick to the light-sensing cells and make otherwise invisible infrared light visible as green light.

Their hunch proved correct, as mice treated with the UCNP solution began seeing in infrared! How could the researchers tell? First, they shined infrared light into the eyes of the mice. Their pupils constricted in response just as they would with visible light. Then the treated mice aced a series of maneuvers in the dark that their untreated counterparts couldn’t manage. The treated animals also could rely on infrared signals to make out shapes.

The research is not only fascinating, but its findings may also have a wide range of intriguing applications. One could imagine taking advantage of the technology for use in hiding encrypted messages in infrared or enabling people to acquire a temporary, built-in ability to see in complete darkness.

With some tweaks and continued research to confirm the safety of these nanoparticles, the system might also find use in medicine. For instance, the nanoparticles could potentially improve vision in those who can’t see certain colors. While such infrared vision technologies will take time to become more widely available, it’s a great example of how one area of science can cross-fertilize another.

References:

[1] Mammalian Near-Infrared Image Vision through Injectable and Self-Powered Retinal Nanoantennae. Ma Y, Bao J, Zhang Y, Li Z, Zhou X, Wan C, Huang L, Zhao Y, Han G, Xue T. Cell. 2019 Feb 27. [Epub ahead of print]

[2] Near-Infrared-Light Activatable Nanoparticles for Deep-Tissue-Penetrating Wireless Optogenetics. Yu N, Huang L, Zhou Y, Xue T, Chen Z, Han G. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019 Jan 11:e1801132.

Links:

Diagram of the Eye (National Eye Institute/NIH)

Infrared Waves (NASA)

Visible Light (NASA)

Han Lab (University of Massachusetts, Worcester)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

‘Tis the Season for Good Cheer

Posted on December 20th, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Oka lab, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena

Whether it’s Rockefeller Center, the White House, or somewhere else across the land, ‘tis the season to gather with neighbors for a communal holiday tree-lighting ceremony. But this festive image has more do with those cups of cider in everyone’s hands than admiring the perfect Douglas fir. What looks like lights and branches are actually components of a high-resolution map from a part of the brain that controls thirst.

The map, drawn up from mouse studies, shows that when thirst arises, neurons activate a gene called c-fos (red)—lighting up the tree—indicating it’s time for a drink. In response, other neurons (green) direct additional parts of the brain to compensate by managing internal water levels. In a mouse that’s no longer thirsty, the tree would look almost all green.

This wiring map comes from a part of the brain called the hypothalamus, which is best known for its role in hunger, thirst, and energy balance. Thanks to powerful molecular tools from NIH’s Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Technologies (BRAIN) Initiative, Yuki Oka of the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, and his team were able to draw detailed maps of the tree-shaped region, called the median preoptic nucleus (MnPO).

Using a technique called optogenetics, Oka’s team, led by Vineet Augustine, could selectively turn on genes in the MnPO [1]. By doing so, they could control a mouse’s thirst and trace the precise control pathways responsible for drinking or not.

This holiday season, as you gather with loved ones, take a moment to savor the beautiful complexity of biology and the gift of human health. Happy holidays to all of you, and peace and joy into the new year!

Reference:

[1] Hierarchical neural architecture underlying thirst regulation. Augustine V, Gokce SK, Lee S, Wang B, Davidson TJ, Reimann F, Gribble F, Deisseroth K, Lois C, Oka Y. Nature. 2018 Mar 8;555(7695):204-209.

Links:

Oka Lab, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena

The BRAIN Initiative (NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Unlocking the Brain’s Memory Retrieval System

Posted on May 24th, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit:Sahay Lab, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

Play the first few bars of any widely known piece of music, be it The Star-Spangled Banner, Beethoven’s Fifth, or The Rolling Stones’ (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, and you’ll find that many folks can’t resist filling in the rest of the melody. That’s because the human brain thrives on completing familiar patterns. But, as we grow older, our pattern completion skills often become more error prone.

This image shows some of the neural wiring that controls pattern completion in the mammalian brain. Specifically, you’re looking at a cross-section of a mouse hippocampus that’s packed with dentate granule neurons and their signal-transmitting arms, called axons, (light green). Note how the axons’ short, finger-like projections, called filopodia (bright green), are interacting with a neuron (red) to form a “memory trace” network. Functioning much like an online search engine, memory traces use bits of incoming information, like the first few notes of a song, to locate and pull up more detailed information, like the complete song, from the brain’s repository of memories in the cerebral cortex.

Posted In: Snapshots of Life

Tags: abLIM3, aging, aging brain, brain, CA neurons, CA3, cerebral cortex, dentate granule cells, dentate gyrus, filopedia, Hippocampal Memory Indexing Theory, hippocampus, memory, memory retrieval, memory trace, mouse hippocampus, neurology, optogenetics, pattern completion, post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD, traumatic memories

Creative Minds: Seeing Memories in a New Light

Posted on November 28th, 2017 by Dr. Francis Collins

Steve Ramirez/Joshua Sariñana

Whether it’s lacing up for a morning run, eating blueberry scones, or cheering on the New England Patriots, Steve Ramirez loves life and just about everything in it. As an undergraduate at Boston University, this joie de vivre actually made Ramirez anxious about choosing just one major. A serendipitous conversation helped him realize that all of the amazing man-made stuff in our world has a common source: the human brain.

So, Ramirez decided to pursue neuroscience and began exploring the nature of memory. Employing optogenetics (using light to control brain cells) in mice, he tagged specific neurons that housed fear-inducing memories, making the neurons light sensitive and amenable to being switched on at will.

In groundbreaking studies that earned him a spot in Forbes 2015 “30 Under 30” list, Ramirez showed that it’s possible to reactivate memories experimentally in a new context, recasting them in either a more negative or positive behavior-changing light [1–3]. Now, with support from a 2016 NIH Director’s Early Independence Award, Ramirez, who runs his own lab at Boston University, will explore whether activating good memories holds promise for alleviating chronic stress and psychiatric disease.

Tags: 2016 NIH Director’s Early Independence Award, amygdala, anxiety, behavior, brain, cerebral cortex, chronic stress, depression, El Salvador, fear, hippocampus, memory, mental illness, mice, neurons, neuroscience, optogenetics, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychiatric disorders, social phobia

Finding Brain Circuits Tied to Alertness

Posted on November 14th, 2017 by Dr. Francis Collins

Everybody knows that it’s important to stay alert behind the wheel or while out walking on the bike path. But our ability to react appropriately to sudden dangers is influenced by whether we feel momentarily tired, distracted, or anxious. How is it that the brain can transition through such different states of consciousness while performing the same routine task, even as its basic structure and internal wiring remain unchanged?

A team of NIH-funded researchers may have found an important clue in zebrafish, a popular organism for studying how the brain works. Using a powerful new method that allowed them to find and track brain circuits tied to alertness, the researchers discovered that this mental state doesn’t work like an on/off switch. Rather, alertness involves several distinct brain circuits working together to bring the brain to attention. As shown in the video above that was taken at cellular resolution, different types of neurons (green) secrete different kinds of chemical messengers across the zebrafish brain to affect the transition to alertness. The messengers shown are: serotonin (red), acetylcholine (blue-green), and dopamine and norepinephrine (yellow).

What’s also fascinating is the researchers found that many of the same neuronal cell types and brain circuits are essential to alertness in zebrafish and mice, despite the two organisms being only distantly related. That suggests these circuits are conserved through evolution as an early fight-or-flight survival behavior essential to life, and they are therefore likely to be important for controlling alertness in people too. If correct, it would tell us where to look in the brain to learn about alertness not only while doing routine stuff but possibly for understanding dysfunctional brain states, ranging from depression to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Posted In: Health, Science, technology

Tags: acetylcholine, alertness, brain, brain circuits, brain imaging, brain states, Danio rerio, depression, dopamine, evolution, evolutionary biology, locus coeruleus, mice, model organism, Multi-MAP, neurology, neuromodulation, neurotransmitter, norepinephrine, optogenetics, PTSD, serotonin, zebrafish