single cell analysis – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

Understanding Childbirth Through a Single-Cell Atlas of the Placenta

Posted on February 13th, 2024 by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

A person in labor. Credit: Adobe/Prostock-studio

While every birth story is unique, many parents would agree that going into labor is an unpredictable process. Although most pregnancies last about 40 weeks, about one in every 10 infants in the U.S. are born before the 37th week of pregnancy, when their brain, lungs, and liver are still developing.1 Some pregnancies also end in an unplanned emergency caesarean delivery after labor fails to progress, for reasons that are largely unknown. Gaining a better understanding of what happens during healthy labor at term may help to elucidate why labor doesn’t proceed normally in some cases.

In a recent development, NIH scientists and their colleagues reported some fascinating new findings that could one day give healthcare providers the tools to better understand and perhaps even predict labor.2 The research team produced an atlas showing the patterns of gene activity that take place in various cell types during labor. To create the atlas, they examined tissues from the placentas of 18 patients not in labor who underwent caesarean delivery and 24 patients in labor. The researchers also analyzed blood samples from another cohort of more than 250 people who delivered at various timepoints. This remarkable study, published in Science Translational Medicine, is the first to analyze gene activity at the single-cell level to better understand the communication that occurs between maternal and fetal cells and tissues during labor.

The placenta is an essential organ for bringing nutrients and oxygen to a growing fetus. It also removes waste, provides immune protection, and supports fetal development. The placenta participates in the process of normal labor at term and preterm labor. Problems with the placenta can lead to many issues, including preterm birth. To create the placental atlas, the study team used an approach called single-cell RNA sequencing. Messenger RNA molecules transcribed or copied from DNA serve as templates for proteins, including those that send important signals between tissues. By sequencing RNAs at the single-cell level, it’s possible to examine gene activity and signaling patterns in many thousands of individual cells at once. This method allows scientists to capture and describe in detail the activities within individual cell types along with interactions among cells of different types and in immune or other key signaling pathways.

Using this approach, the researchers found that cells in the chorioamniotic membranes, which surround the fetus and rupture as part of the labor and delivery process, showed the greatest changes. They also found cells in the mother and fetus that were especially active in generating inflammatory signals. They note that these findings are consistent with previous research showing that inflammation plays an important role in sustaining labor.

Gene activity patterns and changes in the placenta can only be studied after the placenta is delivered. However, it would be ideal if these changes could be identified in the bloodstream of mothers earlier in pregnancy—before labor—so that health care providers can intervene if necessary. The recent study showed that this was possible: Certain gene activity patterns observed in placental cells during labor could be detected in blood tests of women earlier in pregnancy who would later go on to have a preterm birth. The authors note that more research is needed to validate these findings before they can be used as a clinical tool.

Overall, these findings offer important insight into the underlying biology that normally facilitates healthy labor and delivery. They also offer preliminary proof-of-concept evidence that placental biomarkers present in the bloodstream during pregnancy may help to identify pregnancies at increased risk for preterm birth. While much more work and larger studies are needed, these findings suggest that it may one day be possible to identify those at risk for a difficult or untimely labor, when there is still opportunity to intervene.

The research was conducted by the Pregnancy Research Branch part of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and led by Roberto Romero, M.D., D.Med.Sci., NICHD; Nardhy Gomez-Lopez, Ph.D., Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis; and Roger Pique-Regi, Ph.D., Wayne State University, Detroit.

References:

[1] Preterm Birth. CDC.

[2] Garcia-Flores V, et al., Deciphering maternal-fetal crosstalk in the human placenta during parturition using single-cell RNA sequencing. Science Translational Medicine DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adh8335 (2024).

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Tags: childbirth, chorioamniotic, inflammation, labor, placenta, pregnancy, prenatal care, preterm birth, RNA sequencing, single cell analysis, women's health

Finding HIV’s ‘Sweet Spot’

Posted on July 19th, 2022 by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Each year, about 30,000 people in the United States contract the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the cause of AIDS [1]. Thankfully, most can control their HIV infections with antiretroviral therapy and will lead productive, high-quality lives. Many will even reach a point where they have no detectable levels of virus circulating in their blood. However, all must still worry that the undetectable latent virus hidden in their systems could one day reactivate and lead to a range of serious health complications.

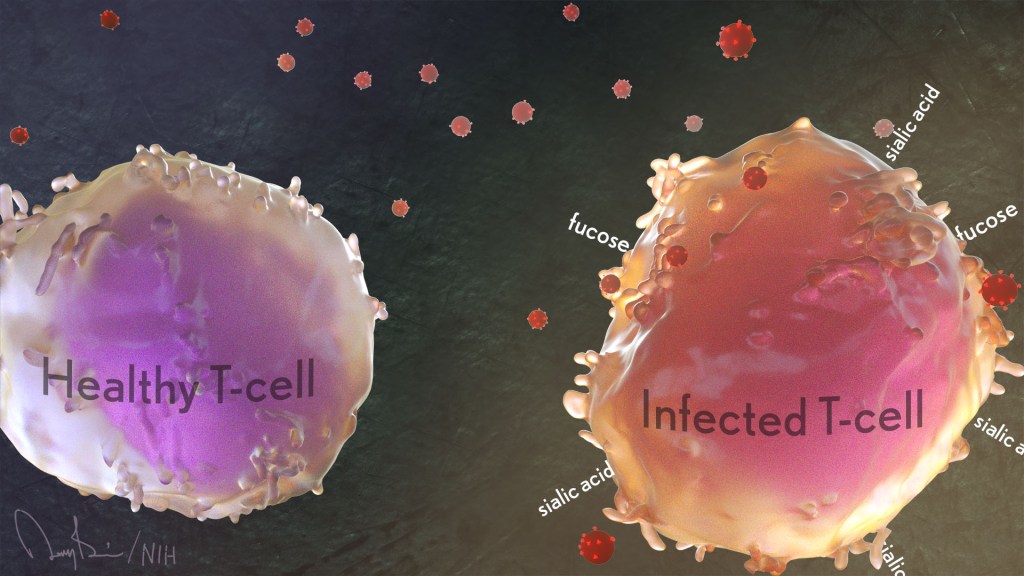

Now, an NIH-funded team has found that patterns of sugars at the surface of our own human immune cells affect their vulnerability to HIV infection. These data suggest it may be possible to find the infected immune cells harboring the last vestiges of virus by reading the sugar profiles on their surfaces. If so, it would move us a step closer to eliminating latent HIV infection and ultimately finding a cure for this horrible virus.

These fascinating new findings come from a team led by Nadia Roan, Gladstone Institutes, San Francisco and Mohamed Abdel-Mohsen, The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA. Among its many areas of study, the Roan lab is interested in why HIV favors infecting specific subsets of a special type of immune cell called memory CD4 T cells. These cells come in different varieties. They also play important roles in the immune system’s ability to recall past infections and launch a rapid response to an emerging repeat infection.

For years, her team and others have tried to understand the interplay between HIV and human immune cells primarily by studying the proteins present at the cell surface. But living cells and their proteins also are coated in sugars and, the presence or absence of these carbohydrates is essential to their biochemistry.

In the new study, published in the journal eLife, the researchers included for the first time the patterns of these sugars in their study of cell surface proteins [2]. They, like many labs, hadn’t done so previously for technical reasons: it’s much easier to track these proteins than sugars.

To overcome this technical hurdle, Roan’s team turned to an approach that it uses for quantifying levels of proteins on the surface of single cells. The method, called CyTOF, uses metal-studded antibodies that stick to proteins, uniquely marking precise patterns of selected proteins, in this case, on individual HIV-infected cells.

In collaboration with Abdel-Mohsen, a glycobiology expert, they adapted this method for cell surface sugars. They did it by adding molecules called lectins, which stick to sugar molecules with specific shapes and compositions.

With this innovation, Roan and team report that they learned to characterize and quantify levels of 34 different proteins on the cell surface simultaneously with five types of sugars. Their next questions were: Could those patterns of cell-surface sugars help them differentiate between different types of immune cells? If so, might those patterns help to define a cell’s susceptibility to HIV?

The answer appears to be yes to both questions. Their studies revealed tremendous diversity in the patterns of sugars at the cells surfaces. Those patterns varied depending on a cell’s tissue of origin—in this case, from blood, tonsil, or the reproductive tract. The patterns also varied depending on the immune cell type—memory CD4 T cells versus other T cells or antibody-producing B cells.

Those sugar and protein profiles offered important clues as to which cells HIV prefers to infect. More specifically, compared to uninfected memory CD4 T cells, the infected ones had higher surface levels of two sugars, known as fucose [3] and sialic acid [4]. What’s more, during HIV infection, levels of both sugars increased.

Scientists already knew that HIV changes the proteins that the infected memory CD4 T cell puts on its surface, a process known as viral remodeling. Now it appears that something similar happens with sugars, too. The new findings suggest the virus increases levels of sialic acid at the cell surface in ways that may help the virus to survive. That’s especially intriguing because sialic acid also is associated with a cell’s ability to avoid detection by the immune system.

The Roan and Abdel-Mohsen labs now plan to team up again to apply their new method to study latent infection. They want to find sugar-based patterns that define those lingering infected cells and see if it’s possible to target them and eliminate the lingering HIV.

What’s also cool is this study indicates that by performing single-cell analyses and sorting cells based on their sugar and protein profiles, it may be possible to discover distinct new classes of immune and other cells that have eluded earlier studies. As was the case with HIV, this broader protein-sugar profile could hold the key to gaining deeper insights into disease processes throughout the body.

References:

[1] Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2020. HIV Surveillance Report, May 2020; 33; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[2] Single-cell glycomics analysis by CyTOF-Lec reveals glycan features defining cells differentially susceptible to HIV. Ma T, McGregor M, Giron L, Xie G, George AF, Abdel-Mohsen M, Roan NR.eLife 2022 July 5;11:e78870

[3] Biological functions of fucose in mammals. Schneider M, Al-Shareffi E, Haltiwanger RS. Glycobiology. 2016 Jun;26(6):543.

[4] Sialic acids and other nonulosonic acids. Lewis AL, Chen X, Schnaar RL, Varki A. In Essentials of Glycobiology [Internet]. 4th edition. Cold Spring Harbor (NY): Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2022.

Links:

HIV/AIDS (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Roan Lab (University of California, San Francisco)

Mohamed Abdel-Mohsen (The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Posted In: News

Tags: AIDS, antibodies, biochemistry, CD4 T cells, cell-surface sugars, CyTOF, fucose, glycobiology, HIV, HIV/AIDS, immunology, latent virus, lectins, memory B cell, memory CD4 T cells, sialic acid, single cell analysis, sugars, T cells, viral remodeling

Single-Cell Study Offers New Clue into Causes of Cystic Fibrosis

Posted on May 27th, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Carraro G, Nature, 2021

More than 30 years ago, I co-led the Michigan-Toronto team that discovered that cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by an inherited misspelling in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene [1]. The CFTR protein’s normal function on the surface of epithelial cells is to serve as a gated channel for chloride ions to pass in and out of the cell. But this function is lost in individuals for whom both copies of CFTR are misspelled. As a consequence, water and salt get out of balance, leading to the production of the thick mucus that leaves people with CF prone to life-threatening lung infections.

It took three decades, but that CFTR gene discovery has now led to the development of a precise triple drug therapy that activates the dysfunctional CFTR protein and provides major benefit to most children and adults with CF. But about 10 percent of individuals with CF have mutations that result in the production of virtually no CFTR protein, which means there is nothing for current triple therapy to correct or activate.

That’s why more basic research is needed to tease out other factors that contribute to CF and, if treatable, could help even more people control the condition and live longer lives with less chronic illness. A recent NIH-supported study, published in the journal Nature Medicine [2], offers an interesting basic clue, and it’s visible in the image above.

The healthy lung tissue (left) shows a well-defined and orderly layer of ciliated cells (green), which use hair-like extensions to clear away mucus and debris. Running closely alongside it is a layer of basal cells (outlined in red), which includes stem cells that are essential for repairing and regenerating upper airway tissue. (DNA indicating the position of cell is stained in blue).

In the CF-affected airways (right), those same cell types are present. However, compared to the healthy lung tissue, they appear to be in a state of disarray. Upon closer inspection, there’s something else that’s unusual if you look carefully: large numbers of a third, transitional cell subtype (outlined in red with green in the nucleus) that combines properties of both basal stem cells and ciliated cells, which is suggestive of cells in transition. The image below more clearly shows these cells (yellow arrows).

Credit: Carraro G, Nature, 2021

The increased number of cells with transitional characteristics suggests an unsuccessful attempt by the lungs to produce more cells capable of clearing the mucus buildup that occurs in airways of people with CF. The data offer an important foundation and reference for continued study.

These findings come from a team led by Kathrin Plath and Brigitte Gomperts, University of California, Los Angeles; John Mahoney, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Lexington, MA; and Barry Stripp, Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles. Together with their lab members, they’re part of a larger research team assembled through the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s Epithelial Stem Cell Consortium, which seeks to learn how the disease changes the lung’s cellular makeup and use that new knowledge to make treatment advances.

In this study, researchers analyzed the lungs of 19 people with CF and another 19 individuals with no evidence of lung disease. Those with CF had donated their lungs for research in the process of receiving a lung transplant. Those with healthy lungs were organ donors who died of other causes.

The researchers analyzed, one by one, many thousands of cells from the airway and classified them into subtypes based on their distinctive RNA patterns. Those patterns indicate which genes are switched on or off in each cell, as well as the degree to which they are activated. Using a sophisticated computer-based approach to sift through and compare data, the team created a comprehensive catalog of cell types and subtypes present in healthy airways and in those affected by CF.

The new catalogs also revealed that the airways of people with CF had alterations in the types and proportions of basal cells. Those differences included a relative overabundance of cells that appeared to be transitioning from basal stem cells into the specialized ciliated cells, which are so essential for clearing mucus from the lungs.

We are not yet at our journey’s end when it comes to realizing the full dream of defeating CF. For the 10 percent of CF patients who don’t benefit from the triple-drug therapy, the continuing work to find other treatment strategies should be encouraging news. Keep daring to dream of breathing free. Through continued research, we can make the story of CF into history!

References:

[1] Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: chromosome walking and jumping. Rommens JM, Iannuzzi MC, Kerem B, Drumm ML, Melmer G, Dean M, Rozmahel R, Cole JL, Kennedy D, Hidaka N, et al. Science.1989 Sep 8;245(4922):1059-65.

[2] Transcriptional analysis of cystic fibrosis airways at single-cell resolution reveals altered epithelial cell states and composition. Carraro G, Langerman J, Sabri S, Lorenzana Z, Purkayastha A, Zhang G, Konda B, Aros CJ, Calvert BA, Szymaniak A, Wilson E, Mulligan M, Bhatt P, Lu J, Vijayaraj P, Yao C, Shia DW, Lund AJ, Israely E, Rickabaugh TM, Ernst J, Mense M, Randell SH, Vladar EK, Ryan AL, Plath K, Mahoney JE, Stripp BR, Gomperts BN. Nat Med. 2021 May;27(5):806-814.

Links:

Cystic Fibrosis (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Kathrin Plath (University of California, Los Angeles)

Brigitte Gomperts (UCLA)

Stripp Lab (Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles)

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (Lexington, MA)

Epithelial Stem Cell Consortium (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Lexington, MA)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Cancer Institute; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Posted In: News

Tags: basal cells, cell biology, CF, CFTR, ciliated cells, cystic fibrosis, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, epithelial cells, Epithelial Stem Cell Consortium, gene expression, lungs, mucus, rare disease, RNA, single cell analysis, single cell sequencing, transitional cell subtype, upper airway

Understanding Neuronal Diversity in the Spinal Cord

Posted on May 20th, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA

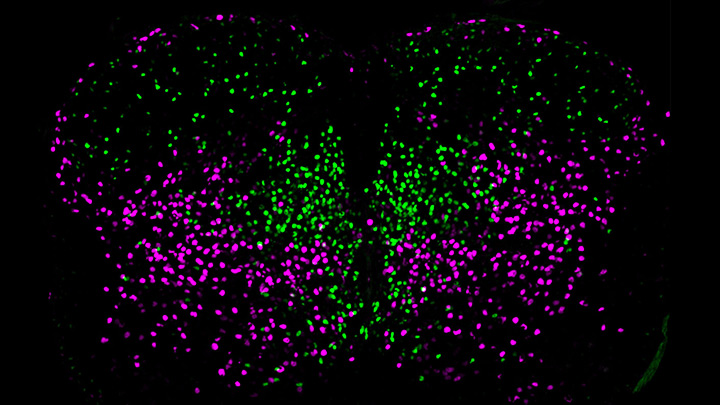

The spinal cord, as a key part of our body’s central nervous system, contains millions of neurons that actively convey sensory and motor (movement) information to and from the brain. Scientists have long sorted these spinal neurons into what they call “cardinal” classes, a classification system based primarily on the developmental origin of each nerve cell. Now, by taking advantage of the power of single-cell genetic analysis, they’re finding that spinal neurons are more diverse than once thought.

This image helps to visualize the story. Each dot represents the nucleus of a spinal neuron in a mouse; humans have a very similar arrangement. Most of these neurons are involved in the regulation of motor control, but they also differ in important ways. Some are involved in local connections (green), such as those that signal outward to a limb and prompt us to pull away reflexively when we touch painful stimuli, such as a hot frying pan. Others are involved in long-range connections (magenta), relaying commands across spinal segments and even upward to the brain. These enable us, for example, to swing our arms while running to help maintain balance.

It turns out that these two types of spinal neurons also have distinctive genetic signatures. That’s why researchers could label them here in different colors and tell them apart. Being able to distinguish more precisely among spinal neurons will prove useful in identifying precisely which ones are affected by a spinal cord injury or neurodegenerative disease, key information in learning to engineer new tissue to heal the damage.

This image comes from a study, published recently in the journal Science, conducted by an NIH-supported team led by Samuel Pfaff, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, CA. Pfaff and his colleagues, including Peter Osseward and Marito Hayashi, realized that the various classes and subtypes of neurons in our spines arose over the course of evolutionary time. They reasoned that the most-primitive original neurons would have gradually evolved subtypes with more specialized and diverse capabilities. They thought they could infer this evolutionary history by looking for conserved and then distinct, specialized gene-expression signatures in the different neural subtypes.

The researchers turned to single-cell RNA sequencing technologies to look for important similarities and differences in the genes expressed in nearly 7,000 mouse spinal neurons. They then used this vast collection of genomic data to group the neurons into closely related clusters, in much the same way that scientists might group related organisms into an evolutionary family tree based on careful study of their DNA.

The first major gene expression pattern they saw divided the spinal neurons into two types: sensory-related and motor-related. This suggested to them that one of the first steps in spinal cord evolution may have been a division of labor of spinal neurons into those two fundamentally important roles.

Further analyses divided the sensory-related neurons into excitatory neurons, which make neurons more likely to fire; and inhibitory neurons, which dampen neural firing. Then, the researchers zoomed in on motor-related neurons and found something unexpected. They discovered the cells fell into two distinct molecular groups based on whether they had long-range or short-range connections in the body. Researches were even more surprised when further study showed that those distinct connectivity signatures were shared across cardinal classes.

All of this means that, while previously scientists had to use many different genetic tags to narrow in on a particular type of neuron, they can now do it with just two: a previously known tag for cardinal class and the newly discovered genetic tag for long-range vs. short-range connections.

Not only is this newfound ability a great boon to basic neuroscientists, it also could prove useful for translational and clinical researchers trying to determine which specific neurons are affected by a spinal injury or disease. Eventually, it may even point the way to strategies for regrowing just the right set of neurons to repair serious neurologic problems. It’s a vivid reminder that fundamental discoveries, such as this one, often can lead to unexpected and important breakthroughs with potential to make a real difference in people’s lives.

Reference:

[1] Conserved genetic signatures parcellate cardinal spinal neuron classes into local and projection subsets. Osseward PJ 2nd, Amin ND, Moore JD, Temple BA, Barriga BK, Bachmann LC, Beltran F Jr, Gullo M, Clark RC, Driscoll SP, Pfaff SL, Hayashi M. Science. 2021 Apr 23;372(6540):385-393.

Links:

What Are the Parts of the Nervous System? (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/NIH)

Spinal Cord Injury (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Samuel Pfaff (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Posted In: Snapshots of Life

Tags: basic research, brain, cardinal spinal classes, central nervous system, evolution, gene expression, genetic signatures, genomics, motor neurons, neurodegenerative disorders, neurons, neuroscience, peripheral nervous system, regenerative medicine, RNA sequencing, sensory neurons, single cell analysis, spinal cord, spinal cord injuries, spinal neurons, tissue engineering

How Severe COVID-19 Can Tragically Lead to Lung Failure and Death

Posted on May 11th, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

More than 3 million people around the world, now tragically including thousands every day in India, have lost their lives to severe COVID-19. Though incredible progress has been made in a little more than a year to develop effective vaccines, diagnostic tests, and treatments, there’s still much we don’t know about what precisely happens in the lungs and other parts of the body that leads to lethal outcomes.

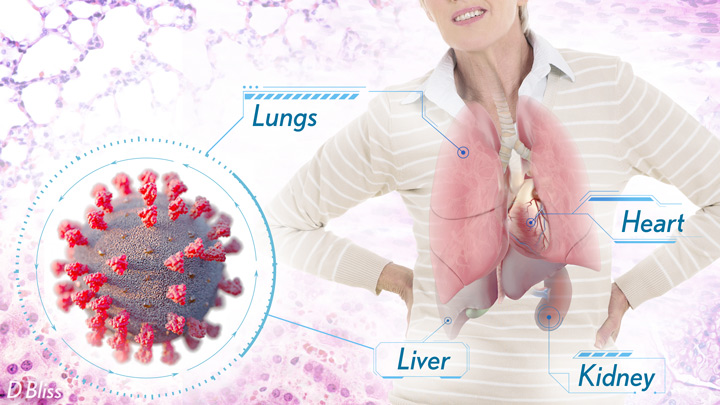

Two recent studies in the journal Nature provide some of the most-detailed analyses yet about the effects on the human body of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 [1,2]. The research shows that in people with advanced infections, SARS-CoV-2 often unleashes a devastating series of host events in the lungs prior to death. These events include runaway inflammation and rampant tissue destruction that the lungs cannot repair.

Both studies were supported by NIH. One comes from a team led by Benjamin Izar, Columbia University, New York. The other involves a group led by Aviv Regev, now at Genentech, and formerly at Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA.

Each team analyzed samples of essential tissues gathered from COVID-19 patients shortly after their deaths. Izar’s team set up a rapid autopsy program to collect and freeze samples within hours of death. He and his team performed single-cell RNA sequencing on about 116,000 cells from the lung tissue of 19 men and women. Similarly, Regev’s team developed an autopsy biobank that included 420 total samples from 11 organ systems, which were used to generate multiple single-cell atlases of tissues from the lung, kidney, liver, and heart.

Izar’s team found that the lungs of people who died of COVID-19 were filled with immune cells called macrophages. While macrophages normally help to fight an infectious virus, they seemed in this case to produce a vicious cycle of severe inflammation that further damaged lung tissue. The researchers also discovered that the macrophages produced high levels of IL-1β, a type of small inflammatory protein called a cytokine. This suggests that drugs to reduce effects of IL-1β might have promise to control lung inflammation in the sickest patients.

As a person clears and recovers from a typical respiratory infection, such as the flu, the lung repairs the damage. But in severe COVID-19, both studies suggest this isn’t always possible. Not only does SARS-CoV-2 destroy cells within air sacs, called alveoli, that are essential for the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide, but the unchecked inflammation apparently also impairs remaining cells from repairing the damage. In fact, the lungs’ regenerative cells are suspended in a kind of reparative limbo, unable to complete the last steps needed to replace healthy alveolar tissue.

In both studies, the lung tissue also contained an unusually large number of fibroblast cells. Izar’s team went a step further to show increased numbers of a specific type of pathological fibroblast, which likely drives the rapid lung scarring (pulmonary fibrosis) seen in severe COVID-19. The findings point to specific fibroblast proteins that may serve as drug targets to block deleterious effects.

Regev’s team also describes how the virus affects other parts of the body. One surprising discovery was there was scant evidence of direct SARS-CoV-2 infection in the liver, kidney, or heart tissue of the deceased. Yet, a closer look heart tissue revealed widespread damage, documenting that many different coronary cell types had altered their genetic programs. It’s still to be determined if that’s because the virus had already been cleared from the heart prior to death. Alternatively, the heart damage might not be caused directly by SARS-CoV-2, and may arise from secondary immune and/or metabolic disruptions.

Together, these two studies provide clearer pictures of the pathology in the most severe and lethal cases of COVID-19. The data from these cell atlases has been made freely available for other researchers around the world to explore and analyze. The hope is that these vast data sets, together with future analyses and studies of people who’ve tragically lost their lives to this pandemic, will improve our understanding of long-term complications in patients who’ve survived. They also will now serve as an important foundational resource for the development of promising therapies, with the goal of preventing future complications and deaths due to COVID-19.

References:

[1] A molecular single-cell lung atlas of lethal COVID-19. Melms JC, Biermann J, Huang H, Wang Y, Nair A, Tagore S, Katsyv I, Rendeiro AF, Amin AD, Schapiro D, Frangieh CJ, Luoma AM, Filliol A, Fang Y, Ravichandran H, Clausi MG, Alba GA, Rogava M, Chen SW, Ho P, Montoro DT, Kornberg AE, Han AS, Bakhoum MF, Anandasabapathy N, Suárez-Fariñas M, Bakhoum SF, Bram Y, Borczuk A, Guo XV, Lefkowitch JH, Marboe C, Lagana SM, Del Portillo A, Zorn E, Markowitz GS, Schwabe RF, Schwartz RE, Elemento O, Saqi A, Hibshoosh H, Que J, Izar B. Nature. 2021 Apr 29.

[2] COVID-19 tissue atlases reveal SARS-CoV-2 pathology and cellular targets. Delorey TM, Ziegler CGK, Heimberg G, Normand R, Shalek AK, Villani AC, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Regev A. et al. Nature. 2021 Apr 29.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Izar Lab (Columbia University, New York)

Aviv Regev (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA)

NIH Support: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Posted In: News

Tags: alveoli, biobank, coronavirus, COVID-19, COVID-19 pathology, cytokines, drug targets, fibroblasts, heart, kidneys, liver, lungs, macrophage, novel coronavirus, pandemic, pulmonary fibrosis, SARS-CoV-2, severe COVID-19, single cell analysis, single-cell atlas, tissue samples

The Prime Cellular Targets for the Novel Coronavirus

Posted on May 5th, 2020 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: NIH

There’s still a lot to learn about SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. But it has been remarkable and gratifying to watch researchers from around the world pull together and share their time, expertise, and hard-earned data in the urgent quest to control this devastating virus.

That collaborative spirit was on full display in a recent study that characterized the specific human cells that SARS-CoV-2 likely singles out for infection [1]. This information can now be used to study precisely how each cell type interacts with the virus. It might ultimately help to explain why some people are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 than others, and how exactly to target the virus with drugs, immunotherapies, and vaccines to prevent or treat infections.

This work was driven by the mostly shuttered labs of Alex K. Shalek, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard, and Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge; and Jose Ordovas-Montanes at Boston Children’s Hospital. In the end, it brought together (if only remotely) dozens of their colleagues in the Human Cell Atlas Lung Biological Network and others across the U.S., Europe, and South Africa.

The project began when Shalek, Ordovas-Montanes, and others read that before infecting human cells, SARS-CoV-2 docks on a protein receptor called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). This enzyme plays a role in helping the body maintain blood pressure and fluid balance.

The group was intrigued, especially when they also learned about a second enzyme that the virus uses to enter cells. This enzyme goes by the long acronym TMPRSS2, and it gets “tricked” into priming the spike proteins that cover SARS-CoV-2 to attack the cell. It’s the combination of these two proteins that provide a welcome mat for the virus.

Shalek, Ordovas-Montanes, and an international team including graduate students, post-docs, staff scientists, and principal investigators decided to dig a little deeper to find out precisely where in the body one finds cells that express this gene combination. Their curiosity took them to the wealth of data they and others had generated from model organisms and humans, the latter as part of the Human Cell Atlas. This collaborative international project is producing a comprehensive reference map of all human cells. For its first draft, the Human Cell Atlas aims to gather information on at least 10 billion cells.

To gather this information, the project relies, in part, on relatively new capabilities in sequencing the RNA of individual cells. Keep in mind that every cell in the body has essentially the same DNA genome. But different cells use different programs to decide which genes to turn on—expressing those as RNA molecules that can be translated into protein. The single-cell analysis of RNA allows them to characterize the gene expression and activities within each and every unique cell type. Based on what was known about the virus and the symptoms of COVID-19, the team focused their attention on the hundreds of cell types they identified in the lungs, nasal passages, and intestines.

As reported in Cell, by filtering through the data to identify cells that express ACE2 and TMPRSS2, the researchers narrowed the list of cell types in the nasal passages down to the mucus-producing goblet secretory cells. In the lung, evidence for activity of these two genes turned up in cells called type II pneumocytes, which line small air sacs known as alveoli and help to keep them open. In the intestine, it was the absorptive enterocytes, which play an important role in the body’s ability to take in nutrients.

The data also turned up another unexpected and potentially important connection. In these cells of interest, all of which are found in epithelial tissues that cover or line body surfaces, the ACE2 gene appeared to ramp up its activity in concert with other genes known to respond to interferon, a protein that the body makes in response to viral infections.

To dig further in the lab, the researchers treated cultured cells that line airways in the lungs with interferon. And indeed, the treatment increased ACE2 expression.

Earlier studies have suggested that ACE2 helps the lungs to tolerate damage. Completely missed was its connection to the interferon response. The researchers now suspect that’s because it hadn’t been studied in these specific human epithelial cells before.

The discovery suggests that SARS-CoV-2 and potentially other coronaviruses that rely on ACE2 may take advantage of the immune system’s natural defenses. When the body responds to the infection by producing more interferon, that in turn results in production of more ACE2, enhancing the ability of the virus to attach more readily to lung cells. While much more work is needed, the finding indicates that any potential use of interferon as a treatment to fight COVID-19 will require careful monitoring to determine if and when it might help patients.

It’s clear that these new findings, from data that weren’t originally generated with COVID-19 in mind, contained several potentially important new leads. This is another demonstration of the value of basic science. We can also rest assured that, with the outpouring of effort from members of the scientific community around the globe to meet this new challenge, progress along these and many other fronts will continue at a remarkable pace.

Reference:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Ziegler, CGK et al. Cell. April 20, 2020.

Links:

Coronaviruses (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Human Cell Atlas (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA)

Shalek Lab (Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

Ordovas-Montanes Lab (Boston Children’s Hospital, MA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Posted In: News

Tags: ACE2, alveoli, basic research, COVID-19, enterocytes, epithelial cells, gene expression, genomics, goblet cells, Human Cell Atlas, Human Cell Atlas Lung Biological Network, infectious diseases, interferon, intestine, lungs, nasal passage, novel coronavirus, pandemic, RNA, SARS-CoV-2, single cell analysis, spike protein, TMPRSS2, type II pneumocytes, viral pandemics

A Neuronal Light Show

Posted on December 23rd, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Chen X, Cell, 2019

These colorful lights might look like a video vignette from one of the spectacular evening light shows taking place this holiday season. But they actually aren’t. These lights are illuminating the way to a much fuller understanding of the mammalian brain.

The video features a new research method called BARseq (Barcoded Anatomy Resolved by Sequencing). Created by a team of NIH-funded researchers led by Anthony Zador, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, NY, BARseq enables scientists to map in a matter of weeks the location of thousands of neurons in the mouse brain with greater precision than has ever been possible before.

How does it work? With BARseq, researchers generate uniquely identifying RNA barcodes and then tag one to each individual neuron within brain tissue. As reported recently in the journal Cell, those barcodes allow them to keep track of the location of an individual cell amid millions of neurons [1]. This also enables researchers to map the tangled paths of individual neurons from one region of the mouse brain to the next.

The video shows how the researchers read the barcodes. Each twinkling light is a barcoded neuron within a thin slice of mouse brain tissue. The changing colors from frame to frame correspond to one of the four letters, or chemical bases, in RNA (A=purple, G=blue, U=yellow, and C=white). A neuron that flashes blue, purple, yellow, white is tagged with a barcode that reads GAUC, while yellow, white, white, white is UCCC.

By sequencing and reading the barcodes to distinguish among seemingly identical cells, the researchers mapped the connections of more than 3,500 neurons in a mouse’s auditory cortex, a part of the brain involved in hearing. In fact, they report they’re now able to map tens of thousands of individual neurons in a mouse in a matter of weeks.

What makes BARseq even better than the team’s previous mapping approach, called MAPseq, is its ability to read the barcodes at their original location in the brain tissue [2]. As a result, they can produce maps with much finer resolution. It’s also possible to maintain other important information about each mapped neuron’s identity and function, including the expression of its genes.

Zador reports that they’re continuing to use BARseq to produce maps of other essential areas of the mouse brain with more detail than had previously been possible. Ultimately, these maps will provide a firm foundation for better understanding of human thought, consciousness, and decision-making, along with how such mental processes get altered in conditions such as autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, and depression.

Here’s wishing everyone a safe and happy holiday season. It’s been a fantastic year in science, and I look forward to bringing you more cool NIH-supported research in 2020!

References:

[1] High-Throughput Mapping of Long-Range Neuronal Projection Using In Situ Sequencing. Chen X, Sun YC, Zhan H, Kebschull JM, Fischer S, Matho K, Huang ZJ, Gillis J, Zador AM. Cell. 2019 Oct 17;179(3):772-786.e19.

[2] High-Throughput Mapping of Single-Neuron Projections by Sequencing of Barcoded RNA. Kebschull JM, Garcia da Silva P, Reid AP, Peikon ID, Albeanu DF, Zador AM. Neuron. 2016 Sep 7;91(5):975-987.

Links:

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Zador Lab (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Cancer Institute

Posted In: Cool Videos

Tags: auditory cortex, Autism Spectrum Disorder, BARseq, brain, brain connections, BRAIN Initiative, brain mapping, decision making, depression, MAPseq, neurons, RNA, RNA barcode, schizophrenia, single cell analysis

The Amazing Brain: Shining a Spotlight on Individual Neurons

Posted on August 13th, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

A major aim of the NIH-led Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative is to develop new technologies that allow us to look at the brain in many different ways on many different scales. So, I’m especially pleased to highlight this winner of the initiative’s recent “Show Us Your Brain!” contest.

Here you get a close-up look at pyramidal neurons located in the hippocampus, a region of the mammalian brain involved in memory. While this tiny sample of mouse brain is densely packed with many pyramidal neurons, researchers used new ExLLSM technology to zero in on just three. This super-resolution, 3D view reveals the intricacies of each cell’s structure and branching patterns.

The group that created this award-winning visual includes the labs of X. William Yang at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Kwanghun Chung at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge. Chung’s team also produced another quite different “Show Us Your Brain!” winner, a colorful video featuring hundreds of neural cells and connections in a part of the brain essential to movement.

Pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus come in many different varieties. Some important differences in their functional roles may be related to differences in their physical shapes, in ways that aren’t yet well understood. So, BRAIN-supported researchers are now applying a variety of new tools and approaches in a more detailed effort to identify and characterize these neurons and their subtypes.

The video featured here took advantage of Chung’s new method for preserving brain tissue samples [1]. Another secret to its powerful imagery was a novel suite of mouse models developed in the Yang lab. With some sophisticated genetics, these models make it possible to label, at random, just 1 to 5 percent of a given neuronal cell type, illuminating their full morphology in the brain [2]. The result was this unprecedented view of three pyramidal neurons in exquisite 3D detail.

Ultimately, the goal of these and other BRAIN Initiative researchers is to produce a dynamic picture of the brain that, for the first time, shows how individual cells and complex neural circuits interact in both time and space. I look forward to their continued progress, which promises to revolutionize our understanding of how the human brain functions in both health and disease.

References:

[1] Protection of tissue physicochemical properties using polyfunctional crosslinkers. Park YG, Sohn CH, Chen R, McCue M, Yun DH, Drummond GT, Ku T, Evans NB, Oak HC, Trieu W, Choi H, Jin X, Lilascharoen V, Wang J, Truttmann MC, Qi HW, Ploegh HL, Golub TR, Chen SC, Frosch MP, Kulik HJ, Lim BK, Chung K. Nat Biotechnol. 2018 Dec 17.

[2] Genetically-directed Sparse Neuronal Labeling in BAC Transgenic Mice through Mononucleotide Repeat Frameshift. Lu XH, Yang XW. Sci Rep. 2017 Mar 8;7:43915.

Links:

Chung Lab (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

Yang Lab (University of California, Los Angeles)

Show Us Your Brain! (BRAIN Initiative/NIH)

Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

Posted In: Cool Videos

Tags: brain, brain imaging, BRAIN Initiative, ExLLSM, hippocampus, imaging, neurology, neurons, neuroscience, pyramidal neurons, Show Us Your Brain, single cell analysis, video

A GPS-like System for Single-Cell Analysis

Posted on July 25th, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

Courtesy of the Chen and Macosko labs

A few years ago, I highlighted a really cool technology called Drop-seq for simultaneously analyzing the gene expression activity inside thousands of individual cells. Today, one of its creators, Evan Macosko, reports significant progress in developing even better tools for single-cell analysis—with support from an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award.

In a paper in the journal Science, Macosko, Fei Chen, and colleagues at the Broad Institute of Harvard and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, recently unveiled another exciting creation called Slide-seq [1]. This technology acts as a GPS-like system for mapping the exact location of each of the thousands of individual cells undergoing genomic analysis in a tissue sample.

This 3D video shows the exquisite precision of this new cellular form of GPS, which was used to generate a high-resolution map of the different cell types found in a tiny cube of mouse brain tissue. Specifically, it provides locations of the cell types and gene expression in the hippocampal regions called CA1 (green), CA2/3 (blue), and dentate gyrus (red).

Because using Slide-seq in the lab requires no specialized imaging equipment or skills, it should prove valuable to researchers across many different biomedical disciplines who want to look at cellular relationships or study gene activity in tissues, organs, or even whole organisms.

How does Slide-seq work? Macosko says one of the main innovations is an inexpensive rubber-coated glass slide nicknamed a puck. About 3 millimeters in diameter, pucks are studded with tens of thousands of 10 micron-sized beads, each one decorated with a random snippet of genetic material—an RNA barcode—that serves as its unique identifier of the bead.

The barcodes are sequenced en masse, and the exact location of each barcoded bead is indexed using innovative software developed by a team led by Chen, who is an NIH Director’s Early Independence awardee.

Then, the researchers place a sample of fresh-frozen tissue (typically, 10 micrometers, or 0.00039 inches, thick) on the puck and dissolve the tissue, lysing the cells and releasing their messenger RNA (mRNA). That leaves only the barcoded beads binding the mRNA transcripts expressed by the cells in the tissue—a biological record of the genes that were turned on at the time the sample was frozen.

The barcoded mRNA is then sequenced. The spatial position of each mRNA molecule can be inferred, using the reference index on the puck. This gives researchers a great deal of biological information about the cells in the tissue, often including their cell type and their gene expression pattern. All the data can then be mapped out in ways similar to those seen in this video, which was created using data from 66 pucks.

Slide-seq has been tested on a range of tissues from both mouse and human, replicating results from similar maps created using existing approaches, but also uncovering new biology. For example, in the mouse cerebellum, Slide-seq allowed the researchers to detect bands of variable gene activity across the tissues. This intriguing finding suggests that there may be subpopulations of cells in this part of the brain that have gene activity influenced by their physical locations.

Such results demonstrate the value of combining cell location with genomic information. In fact, Macosko now hopes to use Slide-seq to study the response of brain cells that are located near the buildup of damaged amyloid protein associated with the early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Meanwhile, Chen is interested in pursuing cell lineage studies in a variety of tissues to see how and where changes in the molecular dynamics of tissues can lead to disease.

These are just a few examples of how Slide-seq will add to the investigative power of single-cell analysis in the years ahead. In meantime, the Macosko and Chen labs are working hard to develop even more innovative approaches to this rapidly emerging areas of biomedical research, so who knows what “seq” we will be talking about next?

Reference:

[1] Slide-seq: A scalable technology for measuring genome-wide expression at high spatial resolution. Rodriques SG, Stickels RR, Goeva A, Martin CA, Murray E, Vanderburg CR, Welch J, Chen LM, Chen F, Macosko EZ. Science. 2019 Mar 29;363(6434):1463-1467.

Links:

Single Cell Analysis (NIH)

Macosko Lab (Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Cambridge)

Chen Lab (Broad Institute)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; Common Fund

Posted In: Cool Videos

Tags: Alzheimer’s disease, brain, cerebellum, Drop-seq, gene expression, genomic analysis, GPS, hippocampus, mRNA, NIH Director's Early Independence Award, NIH Director's New Innovator Award, RNA barcode, single cell analysis, SLIDE-seq, spatial analysis

Biomedical Research Highlighted in Science’s 2018 Breakthroughs

Posted on January 2nd, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

A Happy New Year to one and all! While many of us were busy wrapping presents, the journal Science announced its much-anticipated scientific breakthroughs of 2018. In case you missed the announcement [1], it was another banner year for the biomedical sciences.

The 2018 Breakthrough of the Year went to biomedical science and its ability to track the development of life—one cell at a time—in a variety of model organisms. This newfound ability opens opportunities to understand the biological basis of life more systematically than ever before. Among Science’s “runner-up” breakthroughs, more than half had strong ties to the biomedical sciences and NIH-supported research.

Sound intriguing? Let’s take a closer look at some of the amazing science conducted in 2018, starting with Science’s Breakthrough of the Year.

Development Cell by Cell: For millennia, biologists have wondered how a single cell develops into a complete multicellular organism, such as a frog or a mouse. But solving that mystery was almost impossible without the needed tools to study development systematically, one cell at a time. That’s finally started to change within the last decade. I’ve highlighted the emergence of some of these powerful tools on my blog and the interesting ways that they were being applied to study development.

Over the past few years, all of this technological progress has come to a head. Researchers, many of them NIH-supported, used sophisticated cell labeling techniques, nucleic acid sequencing, and computational strategies to isolate thousands of cells from developing organisms, sequence their genetic material, and determine their location within that developing organism.

In 2018 alone, groundbreaking single-cell analysis papers were published that sequentially tracked the 20-plus cell types that arise from a fertilized zebrafish egg, the early formation of organs in a frog, and even the creation of a new limb in the Axolotl salamander. This is just the start of amazing discoveries that will help to inform us of the steps, or sometimes missteps, within human development—and suggest the best ways to prevent the missteps. In fact, efforts are now underway to gain this detailed information in people, cell by cell, including the international Human Cell Atlas and the NIH-supported Human BioMolecular Atlas Program.

An RNA Drug Enters the Clinic: Twenty years ago, researchers Andrew Fire and Craig Mello showed that certain small, noncoding RNA molecules can selectively block genes in our cells from turning “on” through a process called RNA interference (RNAi). This work, for the which these NIH grantees received the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, soon sparked a wave of commercial interest in various noncoding RNA molecules for their potential to silence the expression of a disease-causing gene.

After much hard work, the first gene-silencing RNA drug finally came to market in 2018. It’s called Onpattro™ (patisiran), and the drug uses RNAi to treat the peripheral nerve disease that can afflict adults with a rare disease called hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. This hard-won success may spark further development of this novel class of biopharmaceuticals to treat a variety of conditions, from cancer to cardiovascular disorders, with potentially greater precision.

Rapid Chemical Structure Determination: Last October, two research teams released papers almost simultaneously that described an incredibly fast new imaging technique to determine the structure of smaller organic chemical compounds, or “small molecules“ at atomic resolution. Small molecules are essential components of molecular biology, pharmacology, and drug development. In fact, most of our current medicines are small molecules.

News of these papers had many researchers buzzing, and I highlighted one of them on my blog. It described a technique called microcrystal electron diffraction, or MicroED. It enabled these NIH-supported researchers to take a powder form of small molecules (progesterone was one example) and generate high-resolution data on their chemical structures in less than a half-hour! The ease and speed of MicroED could revolutionize not only how researchers study various disease processes, but aid in pinpointing which of the vast number of small molecules can become successful therapeutics.

How Cells Marshal Their Contents: About a decade ago, researchers discovered that many proteins in our cells, especially when stressed, condense into circumscribed aqueous droplets. This so-called phase separation allows proteins to gather in higher concentrations and promote reactions with other proteins. The NIH soon began supporting several research teams in their groundbreaking efforts to explore the effects of phase separation on cell biology.

Over the past few years, work on phase separation has taken off. The research suggests that this phenomenon is critical in compartmentalizing chemical reactions within the cell without the need of partitioning membranes. In 2018 alone, several major papers were published, and the progress already has some suggesting that phase separation is not only a basic organizing principle of the cell, it’s one of the major recent breakthroughs in biology.

Forensic Genealogy Comes of Age: Last April, police in Sacramento, CA announced that they had arrested a suspect in the decades-long hunt for the notorious Golden State Killer. As exciting as the news was, doubly interesting was how they caught the accused killer. The police had the Golden Gate Killer’s DNA, but they couldn’t determine his identity, that is, until they got a hit on a DNA profile uploaded by one of his relatives to a public genealogy database.

Though forensic genealogy falls a little outside of our mission, NIH has helped to advance the gathering of family histories and using DNA to study genealogy. In fact, my blog featured NIH-supported work that succeeded in crowdsourcing 600 years of human history.

The researchers, using the online profiles of 86 million genealogy hobbyists with their permission, assembled more than 5 million family trees. The largest totaled more than 13 million people! By merging each tree from the crowd-sourced and public data, they were able to go back about 11 generations—to the 15th century and the days of Christopher Columbus. Though they may not have caught an accused killer, these large datasets provided some novel insights into our family structures, genes, and longevity.

An Ancient Human Hybrid: Every year, researchers excavate thousands of bone fragments from the remote Denisova Cave in Siberia. One such find would later be called Denisova 11, or “Denny” for short.

Oh, what a fascinating genomic tale Denny’s sliver of bone had to tell. Denny was at least 13 years old and lived in Siberia roughly 90,000 years ago. A few years ago, an international research team found that DNA from the mitochondria in Denny’s cells came from a Neanderthal, an extinct human relative.

In 2018, Denny’s family tree got even more interesting. The team published new data showing that Denny was female and, more importantly, she was a first generation mix of a Neanderthal mother and a father who belonged to another extinct human relative called the Denisovans. The Denisovans, by the way, are the first human relatives characterized almost completely on the basis of genomics. They diverged from Neanderthals about 390,000 years ago. Until about 40,000 years ago, the two occupied the Eurasian continent—Neanderthals to the west, and Denisovans to the east.

Denny’s unique genealogy makes her the first direct descendant ever discovered of two different groups of early humans. While NIH didn’t directly support this research, the sequencing of the Neanderthal genome provided an essential resource.

As exciting as these breakthroughs are, they only scratch the surface of ongoing progress in biomedical research. Every field of science is generating compelling breakthroughs filled with hope and the promise to improve the lives of millions of Americans. So let’s get started with 2019 and finish out this decade with more truly amazing science!

Reference:

[1] “2018 Breakthrough of the Year,” Science, 21 December 2018.

NIH Support: These breakthroughs represent the culmination of years of research involving many investigators and the support of multiple NIH institutes.

Posted In: News

Tags: 2018 Breakthrough of the Year, Andrew Fire, axolotl salamander, biopharmaceuticals, cell biology, Craig Mello, Denisovans, developmental biology, forensic genealogy, frog, genome, hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis, Human Cell Atlas, MicroED, Neanderthals, Nobel Prize, noncoding RNA, Onpatrro, patisiran, phase separation, rare disease, RNA, RNA interference, RNAi, Science's Breakthroughs of the Year, single cell analysis, small molecules, zebrafish