TCGA – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

A Global Look at Cancer Genomes

Posted on February 18th, 2020 by Dr. Francis Collins

Cancer is a disease of the genome. It can be driven by many different types of DNA misspellings and rearrangements, which can cause cells to grow uncontrollably. While the first oncogenes with the potential to cause cancer were discovered more than 35 years ago, it’s been a long slog to catalog the universe of these potential DNA contributors to malignancy, let alone explore how they might inform diagnosis and treatment. So, I’m thrilled that an international team has completed the most comprehensive study to date of the entire genomes—the complete sets of DNA—of 38 different types of cancer.

Among the team’s most important discoveries is that the vast majority of tumors—about 95 percent—contained at least one identifiable spelling change in their genomes that appeared to drive the cancer [1]. That’s significantly higher than the level of “driver mutations” found in past studies that analyzed only a tumor’s exome, the small fraction of the genome that codes for proteins. Because many cancer drugs are designed to target specific proteins affected by driver mutations, the new findings indicate it may be worthwhile, perhaps even life-saving in many cases, to sequence the entire tumor genomes of a great many more people with cancer.

The latest findings, detailed in an impressive collection of 23 papers published in Nature and its affiliated journals, come from the international Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) Consortium. Also known as the Pan-Cancer Project for short, it builds on earlier efforts to characterize the genomes of many cancer types, including NIH’s The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC).

In these latest studies, a team including more than 1,300 researchers from around the world analyzed the complete genomes of more than 2,600 cancer samples. Those samples included tumors of the brain, skin, esophagus, liver, and more, along with matched healthy cells taken from the same individuals.

In each of the resulting new studies, teams of researchers dug deep into various aspects of the cancer DNA findings to make a series of important inferences and discoveries. Here are a few intriguing highlights:

• The average cancer genome was found to contain not just one driver mutation, but four or five.

• About 13 percent of those driver mutations were found in so-called non-coding DNA, portions of the genome that don’t code for proteins [2].

• The mutations arose within about 100 different molecular processes, as indicated by their unique patterns or “mutational signatures.” [3,4].

• Some of those signatures are associated with known cancer causes, including aberrant DNA repair and exposure to known carcinogens, such as tobacco smoke or UV light. Interestingly, many others are as-yet unexplained, suggesting there’s more to learn with potentially important implications for cancer prevention and drug development.

• A comprehensive analysis of 47 million genetic changes pieced together the chronology of cancer-causing mutations. This work revealed that many driver mutations occur years, if not decades, prior to a cancer’s diagnosis, a discovery with potentially important implications for early cancer detection [5].

The findings represent a big step toward cataloging all the major cancer-causing mutations with important implications for the future of precision cancer care. And yet, the fact that the drivers in 5 percent of cancers continue to remain mysterious (though they do have RNA abnormalities) comes as a reminder that there’s still a lot more work to do. The challenging next steps include connecting the cancer genome data to treatments and building meaningful predictors of patient outcomes.

To help in these endeavors, the Pan-Cancer Project has made all of its data and analytic tools available to the research community. As researchers at NIH and around the world continue to detail the diverse genetic drivers of cancer and the molecular processes that contribute to them, there is hope that these findings and others will ultimately vanquish, or at least rein in, this Emperor of All Maladies.

References:

[1] Pan-Cancer analysis of whole genomes. ICGC/TCGA Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):82-93.

[2] Analyses of non-coding somatic drivers in 2,658 cancer whole genomes. Rheinbay E et al; PCAWG Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):102-111.

[3] The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Alexandrov LB et al; PCAWG Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):94-101.

[4] Patterns of somatic structural variation in human cancer genomes. Li Y et al; PCAWG Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):112-121.

[5] The evolutionary history of 2,658 cancers. Gerstung M, Jolly C, Leshchiner I, Dentro SC et al; PCAWG Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):122-128.

Links:

The Genetics of Cancer (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Precision Medicine in Cancer Treatment (NCI)

The Cancer Genome Atlas Program (NIH)

NCI and the Precision Medicine Initiative (NCI)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute, National Human Genome Research Institute

Posted In: News

Tags: brain cancer, cancer, cancer genetics, cancer genome, cancer signatures, driver mutations, esophageal cancer, exome, genomics, ICGC, International Cancer Genome Consortium, liver cancer, mutational signatures, non-coding DNA, oncogene, Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium, Pan-Cancer project, PCAWG, precision oncology, skin cancer, TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas, tobacco, UV light, whole genome, whole genome sequencing

Study Finds Genetic Mutations in Healthy Human Tissues

Posted on June 18th, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

The standard view of biology is that every normal cell copies its DNA instruction book with complete accuracy every time it divides. And thus, with a few exceptions like the immune system, cells in normal, healthy tissue continue to contain exactly the same genome sequence as was present in the initial single-cell embryo that gave rise to that individual. But new evidence suggests it may be time to revise that view.

By analyzing genetic information collected throughout the bodies of nearly 500 different individuals, researchers discovered that almost all had some seemingly healthy tissue that contained pockets of cells bearing particular genetic mutations. Some even harbored mutations in genes linked to cancer. The findings suggest that nearly all of us are walking around with genetic mutations within various parts of our bodies that, under certain circumstances, may have the potential to give rise to cancer or other health conditions.

Efforts such as NIH’s The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have extensively characterized the many molecular and genomic alterations underlying various types of cancer. But it has remained difficult to pinpoint the precise sequence of events that lead to cancer, and there are hints that so-called normal tissues, including blood and skin, might contain a surprising number of mutations —perhaps starting down a path that would eventually lead to trouble.

In the study published in Science, a team from the Broad Institute at MIT and Harvard, led by Gad Getz and postdoctoral fellow Keren Yizhak, along with colleagues from Massachusetts General Hospital, decided to take a closer look. They turned their attention to the NIH’s Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project.

The GTEx is a comprehensive public resource that shows how genes are expressed and controlled differently in various tissues throughout the body. To capture those important differences, GTEx researchers analyzed messenger RNA sequences within thousands of healthy tissue samples collected from people who died of causes other than cancer.

Getz, Yizhak, and colleagues wanted to use that extensive RNA data in another way: to detect mutations that had arisen in the DNA genomes of cells within those tissues. To do it, they devised a method for comparing those tissue-derived RNA samples to the matched normal DNA. They call the new method RNA-MuTect.

All told, the researchers analyzed RNA sequences from 29 tissues, including heart, stomach, pancreas, and fat, and matched DNA from 488 individuals in the GTEx database. Those analyses showed that the vast majority of people—a whopping 95 percent—had one or more tissues with pockets of cells carrying new genetic mutations.

While many of those genetic mutations are most likely harmless, some have known links to cancer. The data show that genetic mutations arise most often in the skin, esophagus, and lung tissues. This suggests that exposure to environmental elements—such as air pollution in the lung, carcinogenic dietary substances in the esophagus, or the ultraviolet radiation in sunlight that hits the skin—may play important roles in causing genetic mutations in different parts of the body.

The findings clearly show that, even within normal tissues, the DNA in the cells of our bodies isn’t perfectly identical. Rather, mutations constantly arise, and that makes our cells more of a mosaic of different mutational events. Sometimes those altered cells may have a subtle growth advantage, and thus continue dividing to form larger groups of cells with slightly changed genomic profiles. In other cases, those altered cells may remain in small numbers or perhaps even disappear.

It’s not yet clear to what extent such pockets of altered cells may put people at greater risk for developing cancer down the road. But the presence of these genetic mutations does have potentially important implications for early cancer detection. For instance, it may be difficult to distinguish mutations that are truly red flags for cancer from those that are harmless and part of a new idea of what’s “normal.”

To further explore such questions, it will be useful to study the evolution of normal mutations in healthy human tissues over time. It’s worth noting that so far, the researchers have only detected these mutations in large populations of cells. As the technology advances, it will be interesting to explore such questions at the higher resolution of single cells.

Getz’s team will continue to pursue such questions, in part via participation in the recently launched NIH Pre-Cancer Atlas. It is designed to explore and characterize pre-malignant human tumors comprehensively. While considerable progress has been made in studying cancer and other chronic diseases, it’s clear we still have much to learn about the origins and development of illness to build better tools for early detection and control.

Reference:

[1] RNA sequence analysis reveals macroscopic somatic clonal expansion across normal tissues. Yizhak K, Aguet F, Kim J, Hess JM, Kübler K, Grimsby J, Frazer R, Zhang H, Haradhvala NJ, Rosebrock D, Livitz D, Li X, Arich-Landkof E, Shoresh N, Stewart C, Segrè AV, Branton PA, Polak P, Ardlie KG, Getz G. Science. 2019 Jun 7;364(6444).

Links:

Genotype-Tissue Expression Program

The Cancer Genome Atlas (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Pre-Cancer Atlas (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Getz Lab (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Mental Health; National Cancer Institute; National Library of Medicine; National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke

Posted In: News

Tags: cancer, DNA, esophagus, genetic mutations, genomics, GTEx, lungs, mosaic, mutations, normal tissues, Pre-Cancer Atlas, precancerous lesions, RNA, RNA-MuTect, skin, TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas, The Genotype-Tissue Expression Project

The Cancer Genome Atlas Symposium 2018

Posted on October 4th, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

NIH Researchers Recognized for Service to America

Posted on October 8th, 2015 by Dr. Francis Collins

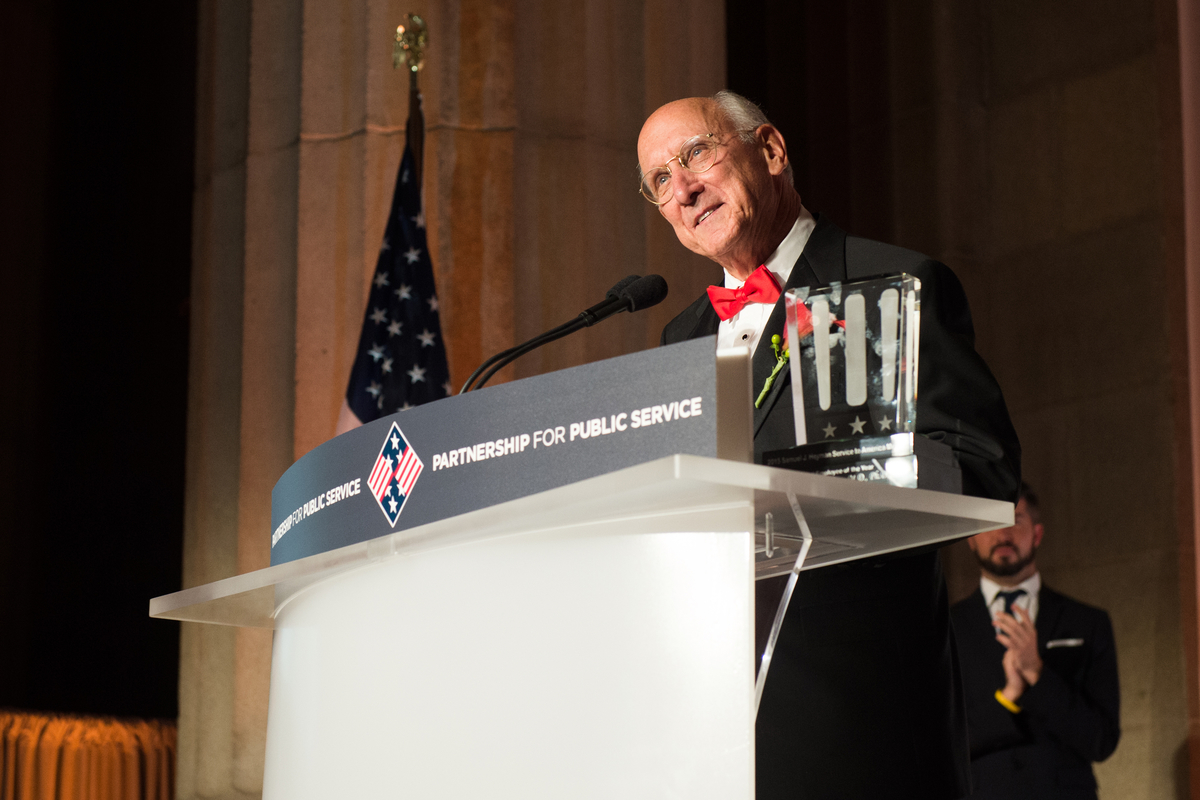

Caption: Steve Rosenberg receiving his Sammie as 2015 Federal Employee of the Year.

Credit: Aaron Clamage/clamagephoto.com

It was a pleasure for me last night to attend the Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medals, also known as “the Sammies.” This Washington, D.C. event, now in its 12th year as the “Oscars of American government service,” was a big night for NIH. Steven Rosenberg, a highly regarded physician-scientist at NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI), took home the evening’s highest honor as the 2015 Federal Employee of the Year.

Also hearing their names called were NCI’s Jean Claude Zenklusen and Carolyn Hutter of NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). They received the inaugural People’s Choice Award. It marks the highest vote-getter from the general public, which was invited to choose from among this year’s 30 finalists in eight award categories.

Caption: Francis Collins presenting 2015 People’s Choice Award medals to Jean Claude Zenklusen and Carolyn Hutter.

Credit: Aaron Clamage/clamagephoto.com

Tags: cancer, Carolyn Hutter, Federal Employee of the Year, immunotherapy, Jean Claude Zenklusen, Partnership for Public Service, public service, Sammies, Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medals, Steve Rosenberg, TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas

Precision Oncology: Creating a Genomic Guide for Melanoma Therapy

Posted on June 23rd, 2015 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Human malignant melanoma cell viewed through a fluorescent, laser-scanning confocal microscope. Invasive structures involved in metastasis appear as greenish-yellow dots, while actin (green) and vinculin (red) are components of the cell’s cytoskeleton.

Credit: Vira V. Artym, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, NIH

It’s still the case in most medical care systems that cancers are classified mainly by the type of tissue or part of the body in which they arose—lung, brain, breast, colon, pancreas, and so on. But a radical change is underway. Thanks to advances in scientific knowledge and DNA sequencing technology, researchers are identifying the molecular fingerprints of various cancers and using them to divide cancer’s once-broad categories into far more precise types and subtypes. They are also discovering that cancers that arise in totally different parts of the body can sometimes have a lot in common. Not only can molecular analysis refine diagnosis and provide new insights into what’s driving the growth of a specific tumor, it may also point to the treatment strategy with the greatest chance of helping a particular patient.

The latest cancer to undergo such rigorous, comprehensive molecular analysis is malignant melanoma. While melanoma can rarely arise in the eye and a few other parts of the body, this report focused on the more familiar “cutaneous melanoma,” a deadly and increasingly common form of skin cancer [1]. Reporting in the journal Cell [2], The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Network says it has identified four distinct molecular subtypes of melanoma. In addition, the NIH-funded network identified an immune signature that spans all four subtypes. Together, these achievements establish a much-needed framework that may guide decisions about which targeted drug, immunotherapy, or combination of therapies to try in an individual with melanoma.

Tags: BRAF, cancer, cancer subtypes, cutaneous melanoma, genomics, immune signature, immunotherapy, LCK, malignant melanoma, melanoma, melanoma biomarker, melanoma subtypes, melanoma therapy, molecular analysis, molecular fingerprint, NF1, precision medicine, Precision Medicine Initiative, precision oncology, RAS, skin cancer, TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas, UV radiation

Different Cancers Can Share Genetic Signatures

Posted on October 22nd, 2013 by Dr. Francis Collins

NIH-funded researchers analyzed the DNA of these cancers.

Cancer is a disease of the genome. It arises when genes involved in promoting or suppressing cell growth sustain mutations that disturb the normal stop and go signals. There are more than 100 different types of cancer, most of which derive their names and current treatment based on their tissue of origin—breast, colon, or brain, for example. But because of advances in DNA sequencing and analysis, that soon may be about to change.

Using data generated through The Cancer Genome Atlas, NIH-funded researchers recently compared the genomic fingerprints of tumor samples from nearly 3,300 patients with 12 types of cancer: acute myeloid leukemia, bladder, brain (glioblastoma multiforme), breast, colon, endometrial, head and neck, kidney, lung (adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma), ovarian, and rectal. Confirming but greatly extending what smaller studies have shown, the researchers discovered that even when cancers originate from vastly different tissues, they can show similar features at the DNA level

Posted In: Science

Tags: acute myeloid leukemia, adenocarcinoma, bladder cancer, breast cancer, cancer, chemotherapy, colon cancer, DNA sequencing, endometrial cancer, gene mutations, genome, genomic fingerprint, glioblastoma multiforme, head and neck cancer, kidney cancer, National Institutes of Health, NIH, ovarian cancer, Pan-Cancer project, personalized medicine, precision medicine, rectal cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas, therapeutic development, treatment, tumor

New Understanding of a Common Kidney Cancer

Posted on July 9th, 2013 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Histologic image of clear cell kidney cancer

Slide courtesy of W. Marston Linehan, National Cancer Institute, NIH

Understanding how cancer cells shift into high gear—what makes them become more aggressive and unresponsive to treatment—is a key concern of cancer researchers. A new study reveals how this escalation occurs in the most common form of kidney cancer: clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). The study shows that ccRCC tumors acquire specific mutations that encourage uncontrollable growth and shifts in energy use and production [1].

Conducted by researchers in the NIH-led The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network, the study compared more than 400 ccRCC tumors from individual patients with healthy tissue samples from the same patients. Researchers were looking for differences in the gene activity and proteins in healthy vs. tumor tissue.

Posted In: Science

Tags: ccRCC, cell growth, chemotherapy, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, epigenome, genes, glycolysis, kidney cancer, mutations, TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, therapy, tumor, VHL