ventilator – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

Clinical Center Doctors Testing 3D-Printed Miniature Ventilator

Posted on November 29th, 2022 by James K. Gilman, MD, NIH Clinical Center

Caption: A USB flash drive (front) next to the 3D-printed miniature ventilator (back). Credit: William Pritchard, Clinical Center, NIH

Here at the NIH Clinical Center, we are proud to be considered a world-renowned research hospital that provides hope through pioneering clinical research to improve human health. But what you may not know is that our doctors are constantly partnering with public and private sectors to come up with innovative technologies that will help to advance health outcomes.

I’m excited to bring to you a story that is perfect example of the ingenuity of our NIH doctors working with global strategic partners to create potentially life-saving technologies. This story begins during the COVID-19 pandemic with the global shortage of ventilators to help patients breathe. Hospitals had a profound need for inexpensive, easy-to-use, rapidly mass-produced resuscitation devices that could be quickly distributed in areas of critical need.

Through strategic partnerships, our Clinical Center doctors learned about and joined an international group of engineers, physicians, respiratory therapists, and patient advocates using their engineering skills to create a ventilator that was functional, affordable, and intuitive. After several iterations and bench testing, they devised a user-friendly ventilator.

Caption: The miniature ventilator connected to an oxygen line (asterisk) and the breathing tube to the patient (crosshatch). The exhaust (dagger) is recessed to prevent accidental blockage. Credit: William Pritchard, Clinical Center, NIH

Then, with the assistance of 3D-printing technology, they improved the original design and did something pretty incredible: the team created the smallest single-patient ventilator seen to date. The device is just 2.4 centimeters (about 1 inch) in diameter with a length of 7.4 centimeters (about 3 inches).

A typical ventilator in a hospital obviously is much larger and has a bellows system. It fills with oxygen and then forces it into the lungs followed by the patient passively exhaling. These systems have multiple moving parts, valves, hoses, and electronic or mechanical controls to manage all aspects of the oxygen flow into the lungs.

But our miniature, 3D-printed ventilator is single use, disposable, and has no moving parts. It’s based on principles of fluidics to ventilate patients by automatically oscillating between forced inspiration and assisted expiration as airway pressure changes. It requires only a continuous supply of pressurized oxygen.

The possibilities of this 3D-printed miniature ventilator are broad. The ventilators could be easily used in emergency transport, potentially treating battlefield casualties or responding to disasters and mass casualty events like earthquakes.

While refining a concept is important, the key is converting it to actual use, which our doctors are doing admirably in their preclinical and clinical studies. NIH’s William Pritchard, Andrew Mannes, Brad Wood, John Karanian, Ivane Bakhutashvili, Matthew Starost, David Eckstein, and medical student Sheridan Reed studied and have already tested the ventilators in swine with acute lung injury, a common severe outcome in a number of respiratory threats including COVID-19.

In the study, the doctors tested three versions of the device built to correspond to mild, moderate, and severe lung injury. The respirators provided adequate support for moderate and mild lung injuries, and the doctors recall how amazing it was initially to witness a 190-pound swine ventilated by this miniature ventilator.

The doctors believe that the 3D-printed miniature ventilator is a potential “game changer” from start to finish since it is lifesaving, small, simple to use, can be easily and inexpensively printed and stored, and does not require additional maintenance. They recently published their preclinical trial results in the journal Science Translational Medicine [1].

The NIH team is preparing to initiate first-in-human trials here at the Clinical Center in the coming months. Perhaps, in the not-too-distant future, a device designed to help people breathe could fit into your pocket next to your phone and keys.

Reference:

[1] In-line miniature 3D-printed pressure-cycled ventilator maintains respiratory homeostasis in swine with induced acute pulmonary injury. Pritchard WF, Karanian JW, Jung C, Bakhutashvili I, Reed SL, Starost MF, Froelke BR, Barnes TR, Stevenson D, Mendoza A, Eckstein DJ, Wood BJ, Walsh BK, Mannes AJ. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Oct 12;14(666):eabm8351.

Links:

Clinical Center (NIH)

Andrew Mannes (Clinical Center)

Bradford Wood (Clinical Center)

David Eckstein (Clinical Center)

Note: Dr. Lawrence Tabak, who performs the duties of the NIH Director, has asked the heads of NIH’s Institutes and Centers (ICs) to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog to highlight some of the interesting science that they support and conduct. This is the 21st in the series of NIH IC guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.

Posted In: Generic

Tags: 3D printing, battlefield, biomedical engineering, breathing, breathing problems, clinical research, clinical trial, COVID-19, disaster response, disposable, emergency medicine, emergency transport, hospital, lungs, microfluidics, miniature ventilator, NIH Clinical Center, pandemic, pre-clinical research, pressurized oxygen, respiratory diseases, resuscitation device, single-use, swine, technology, ventilator

Genes, Blood Type Tied to Risk of Severe COVID-19

Posted on June 18th, 2020 by Dr. Francis Collins

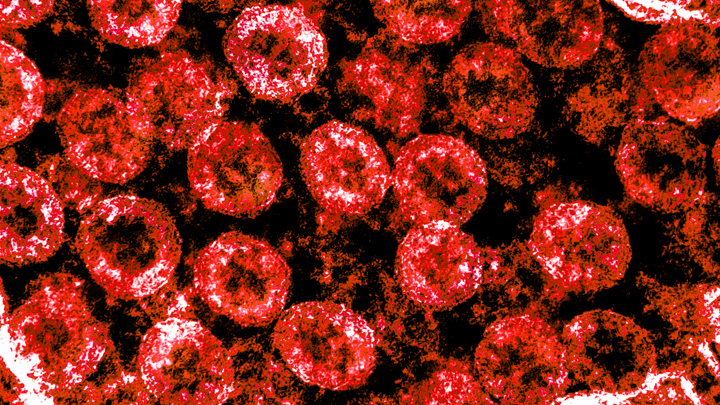

Caption: Micrograph of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles isolated from a patient.

Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

Many people who contract COVID-19 have only a mild illness, or sometimes no symptoms at all. But others develop respiratory failure that requires oxygen support or even a ventilator to help them recover [1]. It’s clear that this happens more often in men than in women, as well as in people who are older or who have chronic health conditions. But why does respiratory failure also sometimes occur in people who are young and seemingly healthy?

A new study suggests that part of the answer to this question may be found in the genes that each one of us carries [2]. While more research is needed to pinpoint the precise underlying genes and mechanisms responsible, a recent genome-wide association (GWAS) study, just published in the New England Journal of Medicine, finds that gene variants in two regions of the human genome are associated with severe COVID-19 and correspondingly carry a greater risk of COVID-19-related death.

The two stretches of DNA implicated as harboring risks for severe COVID-19 are known to carry some intriguing genes, including one that determines blood type and others that play various roles in the immune system. In fact, the findings suggest that people with blood type A face a 50 percent greater risk of needing oxygen support or a ventilator should they become infected with the novel coronavirus. In contrast, people with blood type O appear to have about a 50 percent reduced risk of severe COVID-19.

These new findings—the first to identify statistically significant susceptibility genes for the severity of COVID-19—come from a large research effort led by Andre Franke, a scientist at Christian-Albrecht-University, Kiel, Germany, along with Tom Karlsen, Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet, Norway. Their study included 1,980 people undergoing treatment for severe COVID-19 and respiratory failure at seven medical centers in Italy and Spain.

In search of gene variants that might play a role in the severe illness, the team analyzed patient genome data for more than 8.5 million so-called single-nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs. The vast majority of these single “letter” nucleotide substitutions found all across the genome are of no health significance, but they can help to pinpoint the locations of gene variants that turn up more often in association with particular traits or conditions—in this case, COVID-19-related respiratory failure. To find them, the researchers compared SNPs in people with severe COVID-19 to those in more than 1,200 healthy blood donors from the same population groups.

The analysis identified two places that turned up significantly more often in the individuals with severe COVID-19 than in the healthy folks. One of them is found on chromosome 3 and covers a cluster of six genes with potentially relevant functions. For instance, this portion of the genome encodes a transporter protein known to interact with angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the surface receptor that allows the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, to bind to and infect human cells. It also encodes a collection of chemokine receptors, which play a role in the immune response in the airways of our lungs.

The other association signal popped up on chromosome 9, right over the area of the genome that determines blood type. Whether you are classified as an A, B, AB, or O blood type, depends on how your genes instruct your blood cells to produce (or not produce) a certain set of proteins. The researchers did find evidence suggesting a relationship between blood type and COVID-19 risk. They noted that this area also includes a genetic variant associated with increased levels of interleukin-6, which plays a role in inflammation and may have implications for COVID-19 as well.

These findings, completed in two months under very difficult clinical conditions, clearly warrant further study to understand the implications more fully. Indeed, Franke, Karlsen, and many of their colleagues are part of the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, an ongoing international collaborative effort to learn the genetic determinants of COVID-19 susceptibility, severity, and outcomes. Some NIH research groups are taking part in the initiative, and they recently launched a study to look for informative gene variants in 5,000 COVID-19 patients in the United States and Canada.

The hope is that these and other findings yet to come will point the way to a more thorough understanding of the biology of COVID-19. They also suggest that a genetic test and a person’s blood type might provide useful tools for identifying those who may be at greater risk of serious illness.

References:

[1] Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Wu Z, McGoogan JM, et. al. 2020 Feb 24. [published online ahead of print]

[2] Genomewide association study of severe Covid-19 with respiratory failure. Ellinghaus D, Degenhardt F, et. a. NEJM. June 17, 2020.

Links:

The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative

Andre Franke (Christian-Albrechts-University of Kiel, Germany)

Tom Karlsen (Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet, Norway)

Posted In: News

Tags: ACE2, blood, blood type, Canada, chemokine receptors, COVID-19, gene variants, genes, genome, genome-wide association studies, genomics, GWAS, IL-6, immune system, interleukin-6, Italy, novel coronavirus, oxygen support, pandemic, respiratory failure, SARS-CoV-2, severe COVID-19, Spain, susceptibility, The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, type A, type O, United States, ventilator