wearables – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

Wearable Sensor Promises More Efficient Early Cancer Drug Development

Posted on September 27th, 2022 by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Wearable electronic sensors hold tremendous promise for improving human health and wellness. That promise already runs the gamut from real-time monitoring of blood pressure and abnormal heart rhythms to measuring alcohol consumption and even administering vaccines.

Now a new study published in the journal Science Advances [1] demonstrates the promise of wearables also extends to the laboratory. A team of engineers has developed a flexible, adhesive strip that, at first glance, looks like a Band-Aid. But this “bandage” actually contains an ultra-sensitive, battery-operated sensor that’s activated when placed on the skin of mouse models used to study possible new cancer drugs.

This sensor is so sensitive that it can detect, in real time, changes in the size of a tumor down to one-hundredth of a millimeter. That’s about the thickness of the plastic cling wrap you likely have in your kitchen! The device beams those measures to a smartphone app, capturing changes in tumor growth minute by minute over time.

The goal is to determine much sooner—and with greater automation and precision—which potential drug candidates undergoing early testing in the lab best inhibit tumor growth and, consequently, should be studied further. In their studies in mouse models of cancer, researchers found the new sensor could detect differences between tumors treated with an active drug and those treated with a placebo within five hours. Those quick results also were validated using more traditional methods to confirm their accuracy.

The device is the work of a team led by Alex Abramson, a former post-doc with Zhenan Bao, Stanford University’s School of Engineering, Palo Alto, CA. Abramson has since launched his own lab at the Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta.

The Stanford team began looking for a technological solution after realizing the early testing of potential cancer drugs typically requires researchers to make tricky measurements using pincer-like calipers by hand. Not only is the process tedious and slow, it’s less than an ideal way to capture changes in soft tissues with the desired precision. The imprecision can also lead to false leads that won’t pan out further along in the drug development pipeline, at great time and expense to their developers.

To refine the process, the NIH-supported team turned to wearable technology and recent advances in flexible electronic materials. They developed a device dubbed FAST (short for Flexible Autonomous Sensor measuring Tumors). Its sensor, embedded in a skin patch, is composed of a flexible and stretchable, skin-like polymer with embedded gold circuitry.

Here’s how FAST works: Coated on top of the polymer skin patch is a layer of gold. When stretched, it forms small cracks that change the material’s electrical conductivity. As the material stretches, even slightly, the number of cracks increases, causing the electronic resistance in the sensor to increase as well. As the material contracts, any cracks come back together, and conductivity improves.

By picking up on those changes in conductivity, the device measures precisely the strain on the polymer membrane—an indication of whether the tumor underneath is stable, growing, or shrinking—and transmits that data to a smartphone. Based on that information, potential therapies that are linked to rapid tumor shrinkage can be fast-tracked for further study while those that allow a tumor to continue growing can be cast aside.

The researchers are continuing to test their sensor in more cancer models and with more therapies to extend these initial findings. Already, they have identified at least three significant advantages of their device in early cancer drug testing:

• FAST is non-invasive and captures precise measurements on its own.

• It can provide continuous monitoring, for weeks, months, or over the course of study.

• The flexible sensor fully surrounds the tumor and can therefore detect 3D changes in shape that would be hard to pick up otherwise in real-time with existing technologies.

By now, you are probably asking yourself: Could FAST also be applied as a wearable for cancer patients to monitor in real-time whether an approved chemotherapy regimen is working? It is too early to say. So far, FAST has not been tested in people. But, as highlighted in this paper, FAST is off to, well, a fast start and points to the vast potential of wearables in human health, wellness, and also in the lab.

Reference:

[1] A flexible electronic strain sensor for the real-time monitoring of tumor regression. Abramson A, Chan CT, Khan Y, Mermin-Bunnell A, Matsuhisa N, Fong R, Shad R, Hiesinger W, Mallick P, Gambhir SS, Bao Z. Sci Adv. 2022 Sep 16;8(37):eabn6550.

Links:

Stanford Wearable Electronics Initiative (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA)

Bao Group (Stanford University)

Abramson Lab (Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta)

NIH Support: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

Posted In: News

Tags: cancer, cancer drugs, chemotherapy, drug development, FAST, Flexible Autonomous Sensor Measuring Tumors, mouse models, real-time monitoring, tumor, wearable devices, wearable electronic sensors, wearables

Giving Thanks for Biomedical Research

Posted on November 26th, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

This Thanksgiving, Americans have an abundance of reasons to be grateful—loving family and good food often come to mind. Here’s one more to add to the list: exciting progress in biomedical research. To check out some of that progress, I encourage you to watch this short video, produced by NIH’s National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Engineering (NIBIB), that showcases a few cool gadgets and devices now under development.

Among the technological innovations is a wearable ultrasound patch for monitoring blood pressure [1]. The patch was developed by a research team led by Sheng Xu and Chonghe Wang, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. When this small patch is worn on the neck, it measures blood pressure in the central arteries and veins by emitting continuous ultrasound waves.

Other great technologies featured in the video include:

• Laser-Powered Glucose Meter. Peter So and Jeon Woong Kang, researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, and their collaborators at MIT and University of Missouri, Columbia have developed a laser-powered device that measures glucose through the skin [2]. They report that this device potentially could provide accurate, continuous glucose monitoring for people with diabetes without the painful finger pricks.

• 15-Second Breast Scanner. Lihong Wang, a researcher at California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, and colleagues have combined laser light and sound waves to create a rapid, noninvasive, painless breast scan. It can be performed while a woman rests comfortably on a table without the radiation or compression of a standard mammogram [3].

• White Blood Cell Counter. Carlos Castro-Gonzalez, then a postdoc at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, and colleagues developed a portable, non-invasive home monitor to count white blood cells as they pass through capillaries inside a finger [4]. The test, which takes about 1 minute, can be carried out at home, and will help those undergoing chemotherapy to determine whether their white cell count has dropped too low for the next dose, avoiding risk for treatment-compromising infections.

• Neural-Enabled Prosthetic Hand (NEPH). Ranu Jung, a researcher at Florida International University, Miami, and colleagues have developed a prosthetic hand that restores a sense of touch, grip, and finger control for amputees [5]. NEPH is a fully implantable, wirelessly controlled system that directly stimulates nerves. More than two years ago, the FDA approved a first-in-human trial of the NEPH system.

If you want to check out more taxpayer-supported innovations, take a look at NIBIB’s two previous videos from 2013 and 2018 As always, let me offer thanks to you from the NIH family—and from all Americans who care about the future of their health—for your continued support. Happy Thanksgiving!

References:

[1] Monitoring of the central blood pressure waveform via a conformal ultrasonic device. Wang C, Li X, Hu H, Zhang, L, Huang Z, Lin M, Zhang Z, Yun Z, Huang B, Gong H, Bhaskaran S, Gu Y, Makihata M, Guo Y, Lei Y, Chen Y, Wang C, Li Y, Zhang T, Chen Z, Pisano AP, Zhang L, Zhou Q, Xu S. Nature Biomedical Engineering. September 2018, 687-695.

[2] Evaluation of accuracy dependence of Raman spectroscopic models on the ratio of calibration and validation points for non-invasive glucose sensing. Singh SP, Mukherjee S, Galindo LH, So PTC, Dasari RR, Khan UZ, Kannan R, Upendran A, Kang JW. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2018 Oct;410(25):6469-6475.

[3] Single-breath-hold photoacoustic computed tomography of the breast. Lin L, Hu P, Shi J, Appleton CM, Maslov K, Li L, Zhang R, Wang LV. Nat Commun. 2018 Jun 15;9(1):2352.

[4] Non-invasive detection of severe neutropenia in chemotherapy patients by optical imaging of nailfold microcirculation. Bourquard A, Pablo-Trinidad A, Butterworth I, Sánchez-Ferro Á, Cerrato C, Humala K, Fabra Urdiola M, Del Rio C, Valles B, Tucker-Schwartz JM, Lee ES, Vakoc BJ9, Padera TP, Ledesma-Carbayo MJ, Chen YB, Hochberg EP, Gray ML, Castro-González C. Sci Rep. 2018 Mar 28;8(1):5301.

[5] Enhancing Sensorimotor Integration Using a Neural Enabled Prosthetic Hand System

Links:

Sheng Xu Lab (University of California San Diego, La Jolla)

So Lab (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

Lihong Wang (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena)

Video: Lihong Wang: Better Cancer Screenings

Carlos Castro-Gonzalez (Madrid-MIT M + Visión Consortium, Cambridge, MA)

Video: Carlos Castro-Gonzalez (YouTube)

Ranu Jung (Florida International University, Miami)

Video: New Prosthetic System Restores Sense of Touch (Florida International)

NIH Support: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Cancer Institute; Common Fund

Posted In: Cool Videos

Tags: bioengineering, blood pressure, breast cancer, breast scanner, cancer, chemotherapy, devices, diabetes, finger prick, glucose meter, laser-powered, NEPH, neural-enabled prosthetic hand, neuroprosthetics, NIBIB, non-invasive, prosthetic, prosthetic hand, scanner, tax dollars, technology, Thanksgiving, ultrasound patch, WBC, wearable biosensors, wearable technologies, wearables, white blood cells

Using Artificial Intelligence to Catch Irregular Heartbeats

Posted on January 15th, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: gettyimages/enot-poloskun

Thanks to advances in wearable health technologies, it’s now possible for people to monitor their heart rhythms at home for days, weeks, or even months via wireless electrocardiogram (EKG) patches. In fact, my Apple Watch makes it possible to record a real-time EKG whenever I want. (I’m glad to say I am in normal sinus rhythm.)

For true medical benefit, however, the challenge lies in analyzing the vast amounts of data—often hundreds of hours worth per person—to distinguish reliably between harmless rhythm irregularities and potentially life-threatening problems. Now, NIH-funded researchers have found that artificial intelligence (AI) can help.

A powerful computer “studied” more than 90,000 EKG recordings, from which it “learned” to recognize patterns, form rules, and apply them accurately to future EKG readings. The computer became so “smart” that it could classify 10 different types of irregular heart rhythms, including atrial fibrillation (AFib). In fact, after just seven months of training, the computer-devised algorithm was as good—and in some cases even better than—cardiology experts at making the correct diagnostic call.

EKG tests measure electrical impulses in the heart, which signal the heart muscle to contract and pump blood to the rest of the body. The precise, wave-like features of the electrical impulses allow doctors to determine whether a person’s heart is beating normally.

For example, in people with AFib, the heart’s upper chambers (the atria) contract rapidly and unpredictably, causing the ventricles (the main heart muscle) to contract irregularly rather than in a steady rhythm. This is an important arrhythmia to detect, even if it may only be present occasionally over many days of monitoring. That’s not always easy to do with current methods.

Here’s where the team, led by computer scientists Awni Hannun and Andrew Ng, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, saw an AI opportunity. As published in Nature Medicine, the Stanford team started by assembling a large EKG dataset from more than 53,000 people [1]. The data included various forms of arrhythmia and normal heart rhythms from people who had worn the FDA-approved Zio patch for about two weeks.

The Zio patch is a 2-by-5-inch adhesive patch, worn much like a bandage, on the upper left side of the chest. It’s water resistant and can be kept on around the clock while a person sleeps, exercises, or takes a shower. The wireless patch continuously monitors heart rhythms, storing EKG data for later analysis.

The Stanford researchers looked to machine learning to process all the EKG data. In machine learning, computers rely on large datasets of examples in order to learn how to perform a given task. The accuracy improves as the machine “sees” more data.

But the team’s real interest was in utilizing a special class of machine learning called deep neural networks, or deep learning. Deep learning is inspired by how our own brain’s neural networks process information, learning to focus on some details but not others.

In deep learning, computers look for patterns in data. As they begin to “see” complex relationships, some connections in the network are strengthened while others are weakened. The network is typically composed of multiple information-processing layers, which operate on the data and compute increasingly complex and abstract representations.

Those data reach the final output layer, which acts as a classifier, assigning each bit of data to a particular category or, in the case of the EKG readings, a diagnosis. In this way, computers can learn to analyze and sort highly complex data using both more obvious and hidden features.

Ultimately, the computer in the new study could differentiate between EKG readings representing 10 different arrhythmias as well as a normal heart rhythm. It could also tell the difference between irregular heart rhythms and background “noise” caused by interference of one kind or another, such as a jostled or disconnected Zio patch.

For validation, the computer attempted to assign a diagnosis to the EKG readings of 328 additional patients. Independently, several expert cardiologists also read those EKGs and reached a consensus diagnosis for each patient. In almost all cases, the computer’s diagnosis agreed with the consensus of the cardiologists. The computer also made its calls much faster.

Next, the researchers compared the computer’s diagnoses to those of six individual cardiologists who weren’t part of the original consensus committee. And, the results show that the computer actually outperformed these experienced cardiologists!

The findings suggest that artificial intelligence can be used to improve the accuracy and efficiency of EKG readings. In fact, Hannun reports that iRhythm Technologies, maker of the Zio patch, has already incorporated the algorithm into the interpretation now being used to analyze data from real patients.

As impressive as this is, we are surely just at the beginning of AI applications to health and health care. In recognition of the opportunities ahead, NIH has recently launched a working group on AI to explore ways to make the best use of existing data, and harness the potential of artificial intelligence and machine learning to advance biomedical research and the practice of medicine.

Meanwhile, more and more impressive NIH-supported research featuring AI is being published. In my next blog, I’ll highlight a recent paper that uses AI to make a real difference for cervical cancer, particularly in low resource settings.

Reference:

[1] Cardiologist-level arrhythmia detection and classification in ambulatory electrocardiograms using a deep neural network. Hannun AY, Rajpurkar P, Haghpanahi M, Tison GH, Bourn C, Turakhia MP, Ng AY.

Nat Med. 2019 Jan;25(1):65-69.

Links:

Arrhythmia (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Video: Artificial Intelligence: Collecting Data to Maximize Potential (NIH)

Andrew Ng (Palo Alto, CA)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Posted In: News

Tags: AFib, AI, AI Working Group, artificial intelligence, atrial fibrillation, big data, cardiology, computer learning, deep learning, EKG, electrocardiogram, heart, iRhythm Technologies, irregular heartbeat, machine learning, wearable devices, wearable patch, wearables, Zio Patch

Taking Microfluidics to New Lengths

Posted on November 6th, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Microfluidic fiber sorting a solution containing either live or dead cells. The type of cell being imaged and the real time voltage (30v) is displayed at bottom. It is easy to imagine how this could be used to sort a mixture of live and dead cells. Credit: Yuan et al., PNAS

Microfluidics—the manipulation of fluids on a microscopic scale— has made it possible to produce “lab-on-a-chip” devices that detect, for instance, the presence of Ebola virus in a single drop of blood. Now, researchers hope to apply the precision of microfluidics to a much broader range of biomedical problems. Their secret? Move the microlab from chips to fibers.

To do this, an NIH-funded team builds microscopic channels into individual synthetic polymer fibers reaching 525 feet, or nearly two football fields long! As shown in this video, the team has already used such fibers to sort live cells from dead ones about 100 times faster than current methods, relying only on natural differences in the cells’ electrical properties. With further design and development, the new, fiber-based systems hold great promise for, among other things, improving kidney dialysis and detecting metastatic cancer cells in a patient’s bloodstream.

Posted In: News

Tags: 3D printing, brainstorming, cell sorting, devices, diagnostics, electrical fields, fibers, kidney dialysis, lab on a chip, materials science, metastatic cancer, mHealth, microfluidic fibers, microfluidics, microlab, polycarbonate, speedstorming, video, wearables

Wearable Ultrasound Patch Monitors Blood Pressure

Posted on November 1st, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

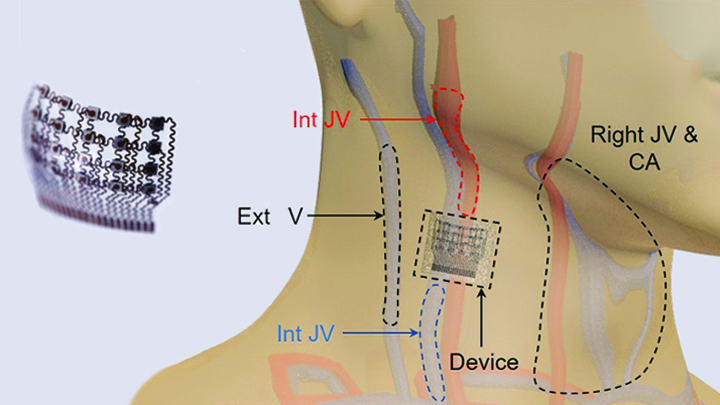

Caption: Worn on the neck, the device records central blood pressure in the carotid artery (CA), internal jugular vein (Int JV) and external jugular vein (Ext JV).

Credit: Adapted from Wang et al, Nature Biomedical Engineering

There’s lots of excitement out there about wearable devices quietly keeping tabs on our health—morning, noon, and night. Most wearables monitor biological signals detectable right at the surface of the skin. But, the sensing capabilities of the “skin” patch featured here go far deeper than that.

As described recently in Nature Biomedical Engineering, when this small patch is worn on the neck, it measures blood pressure way down in the central arteries and veins more than an inch beneath the skin [1]. The patch works by emitting continuous ultrasound waves that monitor subtle, real-time changes in the shape and size of pulsing blood vessels, which indicate rises or drops in pressure.

Posted In: News

Tags: bioengineering, biosensor, blood, blood pressure, carotid artery, central blood pressure, circulation, devices, heart failure, hypertension, irregular heartbeat, jugular vein, sensors, ultrasound, ultrasound patch, waveform, wearable biosensors, wearables

Building a Smarter Bandage

Posted on July 26th, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Tufts University, Medford, MA

Smartphones, smartwatches, and smart electrocardiograms. How about a smart bandage?

This image features a prototype of a smart bandage equipped with temperature and pH sensors (lower right) printed directly onto the surface of a thin, flexible medical tape. You also see the “brains” of the operation: a microprocessor (upper left). When the sensors prompt the microprocessor, it heats up a hydrogel heating element in the bandage, releasing drugs and/or other healing substances on demand. It can also wirelessly transmit messages directly to a smartphone to keep patients and doctors updated.

While the smart bandage might help mend everyday cuts and scrapes, it was designed with the intent of helping people with hard-to-heal chronic wounds, such as leg and foot ulcers. Chronic wounds affect millions of Americans, including many seniors [1]. Such wounds are often treated at home and, if managed incorrectly, can lead to infections and potentially serious health problems.

Posted In: News

Tags: bandage, bioengineering, chronic wounds, diabetes, foot ulcers, hydrogel, microprocessor, skin, smart bandage, smart devices, smart technologies, smartphone, wearable biosensors, wearable sensors, wearables, wound healing, wounds

Wearable mHealth Device Detects Abnormal Heart Rhythms Earlier

Posted on July 17th, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Woman wearing a Zio patch

Credit: Adapted from JAMA Network Summary Video

As many as 6 million Americans experience a common type of irregular heartbeat, called atrial fibrillation (AFib), that can greatly increase their risk of stroke and heart failure [1]. There are several things that can be done to lower that risk, but the problem is that a lot of folks have no clue that their heart’s rhythm is out of whack!

So, what can we do to detect AFib and get people into treatment before it’s too late? New results from an NIH-funded study lend additional support to the idea that one answer may lie in wearable health technology: a wireless electrocardiogram (EKG) patch that can be used to monitor a person’s heart rate at home.

Posted In: News

Tags: Aetna, AFib, All of Us, atrial fibrillation, cardiology, direct-to-participant clinical study, early detection, EKG, electrocardiogram, heart, heart arrhythmia, heart failure, iRhythm Technologies, mHealth, mHealth screening, mobile health, mSToPS, stroke, translational science, wearable devices, wearables, Zio Patch

Built for the Future. Study Shows Wearable Devices Can Help Detect Illness Early

Posted on January 17th, 2017 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Stanford University’s Michael Snyder displays some of his wearable devices.

Credit: Steve Fisch/Stanford School of Medicine

Millions of Americans now head out the door each day wearing devices that count their steps, check their heart rates, and help them stay fit in general. But with further research, these “wearables” could also play an important role in the early detection of serious medical conditions. In partnership with health-care professionals, people may well use the next generation of wearables to monitor vital signs, blood oxygen levels, and a wide variety of other measures of personal health, allowing them to see in real time when something isn’t normal and, if unusual enough, to have it checked out right away.

In the latest issue of the journal PLoS Biology [1], an NIH-supported study offers an exciting glimpse of this future. Wearing a commercially available smartwatch over many months, more than 40 adults produced a continuous daily stream of accurate personal health data that researchers could access and monitor. When combined with standard laboratory blood tests, these data—totaling more than 250,000 bodily measurements a day per person—can detect early infections through changes in heart rate.

Tags: Basis smartwatches, blood oxygen, body temperature, circadian rhythm, digital health, iHealth finger, Lyme disease, Masimo Pulse Ox, mHealth, MOVES, personalized medicine, precision medicine, Precision Medicine Initiative All of Us Research Program, RadTarge, Scanadu Scout, smartwatch, wearable biosensors, wearable devices, wearable sensors, wearables, Withings scale