Interferon-γ potentiates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced death by reducing pancreatic beta cell defence mechanisms (original) (raw)

Introduction

A detailed understanding of the signals activating the apoptotic programme in beta cells is crucial for the design of new therapies to prevent immune-mediated beta cell death in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Accumulating evidence suggests that a tight control of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) homeostasis is important for the maintenance of beta cell function and survival [1–3]. The ER is the main site for calcium storage and signalling, protein synthesis and folding and lipid biosynthesis [4, 5]. To function properly the ER relies on numerous resident chaperone proteins, a high calcium content and an oxidative environment [4, 5]. Alterations of the ER environment, such as Ca2+ depletion, altered glycosylation or perturbed redox status, may trigger accumulation of unfolded proteins and activate a specific ER stress response, known as the unfolded protein response (UPR) [4, 5]. This response is crucial both for cell recovery under conditions of ER stress and for the function and survival of active secretory cells, such as beta cells [1–3]. The UPR involves translational attenuation via autophosphorylation of protein kinase RNA-dependent (PKR)-like ER kinase (PERK), an increase in the folding capacity of the ER by upregulation of ER chaperones and degradation of misfolded proteins via the ER-associated degradation pathway (ERAD) [5, 6]. Transcriptional upregulation of ER chaperones is crucial for cellular recovery following ER stress because these proteins prevent additional protein aggregation by promoting proper folding and by assembling and targeting misfolded proteins for degradation [4]. Two main transcription factors regulate chaperone induction, namely activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) and X-box binding protein-1 (XBP1). During the UPR the luminal domain of ATF6 is released from the ER chaperone immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein (BiP; also known as heat shock 70 kDa protein 5) and translocates to the Golgi complex. ATF6 is then cleaved and its active part, encoding the basic leucine zipper transcription factor, translocates to the nucleus [4, 5]. Inositol requiring ER-to-nucleus signal kinase 1 α (IRE1α) is also bound to BiP in the ER lumen; BiP is removed during ER stress, leading to oligomerisation, autophosphorylation and activation of the RNase domain of IRE1α. This domain will then cleave Xbp1 mRNA, leading to the formation of an active transcription factor [4, 5]. Three _cis_-acting elements capable of binding to ATF6, XBP1, or both have been identified, namely ER stress-response element (ERSE), unfolded protein response element (UPRE) and ERSE-II [5]. Under prolonged or excessive ER stress the apoptotic machinery is induced, but the mechanisms linking ER stress and apoptosis remain to be clarified [5, 6].

Cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α and IFN-γ contribute to beta cell death in type 1 diabetes [7]. We have recently described how IL-1β plus IFN-γ, via nitric oxide (NO) synthesis, inhibit expression of the ER Ca2+ pump SERCA2 and deplete ER Ca2+ stores in beta cells, leading to ER stress and apoptosis [8]. This ER stress response includes activation of the IRE-1α and PERK pathways, and increased expression of the C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP; also known as DNA-damage-inducible transcript 3) [8]. IL-1β alone induced ER stress but failed to induce beta cell death in the absence of IFN-γ, while IFN-γ neither caused ER stress nor induced beta cell death [8]. We have previously observed, by microarray analysis of primary beta cells, that exposure to IFN-γ downregulates the mRNAs that encode for several ER chaperones such as oxygen-related protein (ORP) 150 (also known as hypoxia up-regulated 1), calreticulin and calbindin, and a component of the ER-protein translocator, SEC61a [9]. This raised the possibility that IFN-γ aggravates the ER stress induced by IL-1β by decreasing beta cell ER defences. Notably, IFN-γ augments IL-1β-induced inducible NO synthase expression and NO production [8] making it difficult to discriminate between the putative effects of IFN-γ on ER stress defences and the effects mediated via enhanced NO production. For this reason, we used a reversible blocker of the SERCA pump, cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), to induce a ‘pure’ ER stress in beta cells and then evaluated the effects of IFN-γ on CPA-induced beta cell UPR activation and apoptosis.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

INS-1E cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Paisley, UK) [10]. FACS-purified rat beta cells were isolated and cultured in Ham’s F-10 medium (Gibco) as described previously [8, 11]. Both INS-1E cells and primary beta cells were plated and cultured for 48 h before the addition of test agents. Recombinant rat IFN-γ (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) was used at 0.036 μg/ml (corresponding to approximately 100 U/ml of recombinant mouse IFN-γ) and human recombinant IL-1β (a gift from Dr C.W. Reinolds, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD) was used at 10 U/ml. Cytokine concentrations were chosen with reference to previous dose–response experiments ([7, 8, 10]; Kutlu and Eizirik unpublished data). The reversible SERCA blocker CPA was tested at different concentrations (3.1, 6.25 and 25 μmol/l) to induce ER stress.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis and evaluation of Xbp-1 processing

INS-1E cells were pretreated for 24 h with IFN-γ or left untreated. The cells were then further exposed for 6 or 12 h to 3.1, 6.25 or 25 μmol/l CPA or to the carrier solvent of CPA (DMSO, 0.25%) as control, in the presence or absence of IFN-γ. DMSO at this concentration affects neither INS-1E cell and beta cell viability nor gene expression (data not shown, [8]). The rationale for preculturing the cells with IFN-γ instead of adding it in conjunction with the CPA is that we have previously observed in our microarray experiments that beta cell exposure to IFN-γ downregulates the expression of several ER chaperone genes and Sec61a after 6–24 h [9]. Thus, we intended to test whether IFN-γ-mediated downregulation of ER ‘defence genes’ would aggravate the ER stress induced by CPA.

Cells were then collected, poly(A)+ RNA was extracted and the reverse transcriptase reaction was performed as previously described [12]. Expression of Chop, Xbp1, Bip, Orp150, glucose regulated protein 94 (Grp94; also known as tumour rejection antigen 1), calbindin, calreticulin and Sec61a mRNAs was determined by real-time RT-PCR using SYBR green fluorescence on a Light Cycler (Roche Diagnosis, Manheim, Germany) by the standard curve method [13, 14]. The housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) was used for confirmation of similar cDNA loading. Results are shown as expression of the gene of interest divided by that of Gapdh. The PCR amplification reactions and preparation of standards were performed as previously described [13]. Primers for real-time RT-PCR were as follows: Xbp1: forward (F)-GAGCAGCAAGTGGTGGATTT, reverse (R)-TCTCAATCACAAGCCCATGA (115 bp); Orp150: F-TCAGATGCCAAAGAGAATGG, R-TTCAGCTTCCTCCTTGAGTTC (111 bp); Grp94: F-AAGGTCATTGTCACGTCGAAA, R-GTGTTTCCTCTTGGGTCAGC (98 bp); calbindin: F-AAGCAAACAAGACCGTGGAT, R-CATCTCTGTCAGCTCCAGCTT (104 bp); calreticulin: F-GATTCGAACCCTTCAGCAAC, R-GGAAACAGCTTCACGTAGCC (104 bp); Sec61a: F-TGTATTCATGCTGGGTTCCT, R-ATCACCATCTGCTGCTCCTT (108 bp). Primer sequences for Bip, Chop, atf4 and Gapdh are described elsewhere [8]. The experiments for the determination of mRNA expression were performed in duplicate, and the means of the duplicates were considered as _n_=1.

IRE1α-mediated Xbp1 processing is characterised by excision of a 26-bp sequence from the coding region of Xbp1 mRNA [15]. The cleaved fragment was evaluated by PCR followed by restriction analysis [8, 16]. Gel images were captured and optical density of the bands was determined using the KODAK 1D image analysis software. The amount of spliced Xbp1 (_Xbp1_s) product, indicating UPR activation, was expressed as a percentage of the summed intensity of the unspliced Xbp1 (_Xbp1_u) and _Xbp1_s bands.

Assessment of cell viability

INS-1E cells (6,000 cells/condition) or FACS-purified rat beta cells (10,000 cells/condition) were cultured attached to 96-well dishes and pretreated for 24 h in the presence or absence of IFN-γ or IL-1β; or for 6 h with 12.5 μmol/l CPA or control (DMSO, 0.125%). After CPA pretreatment the cells where washed then cultured for 4 h before further treatment. INS-1E cells or beta cells were then treated with CPA in the presence or absence of IFN-γ or IL-1β. The percentage of viable, necrotic and apoptotic cells was determined by inverted fluorescence microscopy with the DNA dyes Hoechst 342 (10 μg/ml) and propidium iodide (10 μg/ml) [8, 17]. Viability was evaluated by at least two independent observers, with one of them unaware of sample identity. The agreement between findings obtained by the two observers was always >90%. The apoptotic index was calculated as \({\left( {{{\left[ {{\text{\% apoptotic cells in experimental condition - \% apoptotic cells in control}}} \right]}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\left[ {{\text{\% apoptotic cells in experimental condition - \% apoptotic cells in control}}} \right]}} {{\left[ {{\text{100 - \% dead cells in control}}} \right]}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {{\left[ {{\text{100 - \% dead cells in control}}} \right]}}} \right)} \times 100\) [17, 18].

UPRE luciferase reporter assay

The reporter plasmid containing the luciferase gene under the control of five UPREs was kindly provided by Prof. Prywes (Columbia University, New York, NY). INS-1E cells were plated at a density of 140,000 cells/condition in 24-well plates and co-transfected with the UPRE and pRL-CMV plasmids (internal control for transfection efficiency) as described elswhere [19]. Twenty-four hours after transfection the cells were treated with IFN-γ and CPA as described above. Luciferase activities in the cell lysates were determined in a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Test values were corrected for luciferase value of the internal control plasmid (pRL-CMV).

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as mean±SEM, and comparisons between groups were made by paired t test or by ANOVA followed by t test with the Bonferroni correction, as indicated. A p value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

CPA induces ER stress and UPR in INS-1E cells

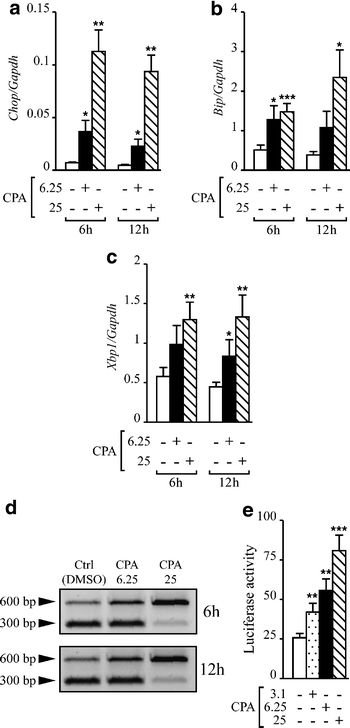

To validate the use of CPA as an ER stress-inducing agent, we initially characterised different components of the UPR/ER stress response induced by CPA in INS-1E cells. For this purpose INS-1E cells were exposed for 6 or 12 h to different concentrations of CPA. A low concentration of CPA (6.25 μmol/l) was sufficient to trigger the UPR response, as indicated by induction of Chop (Fig. 1a), Bip (Fig. 1b) and Xbp1 (Fig. 1c) mRNA expression. These effects were more pronounced in INS-1E cells exposed to 25 μmol/l CPA (Fig. 1). IRE-1α-mediated splicing of Xbp1 in INS-1E cells under basal conditions (upper band 600 bp, Fig. 1d) was 33.2±2.5% and 32.8±1.5% of the total Xbp1 mRNA at 6 and 12 h, respectively. Exposure to 6.25 and 25 μmol/l CPA for 6 h increased the levels of _Xbp1_s to 44.9±2.2 and 77±2.3%, respectively (p<0.001 vs control). Twelve hours after treatment, a significant increase of the _Xbp1_s product (72.3±8.8%, p<0.01 vs control) was still observed in INS-1E cells exposed to 25 μmol/l CPA while it had returned to base levels in cells treated with 6.25 μmol/l CPA. Confirming the triggering of ER stress, CPA induced a dose-dependent activation of the luciferase reporter plasmid under the control of five UPRE [20] (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1

CPA induces ER stress in INS-1E cells. Cells were exposed for 6 or 12 h to CPA (6.25 or 25 μmol/l) or control conditions (DMSO 0.25%); mRNA was then extracted and real-time RT-PCR was performed using specific primers for Chop (a), Bip (b) or Xbp1 (c). Expression of the gene of interest was corrected for Gapdh expression. The results are the means±SEM of six experiments. d mRNA was extracted after CPA treatment and cDNA was utilised as a template for PCR using _Xbp1_-specific primers. After amplification, PCR products were incubated with the restriction enzyme _Pst_I. PCR products derived from spliced Xbp1 are left intact (600 bp), indicating the presence of ER stress. The figure shown is representative of six experiments. e INS-1E cells were co-transfected with a construct containing five UPREs upstream of the luciferase reporter gene and the internal control pRL-CMV, encoding Renilla luciferase. After overnight transfection, the cells were exposed for 15 h to CPA (3.1, 6.25 or 25 μmol/l) or control and were assayed for firefly and Renilla luciferase activities. The results were normalised for Renilla luciferase activity (_n_=5). *_p_≤0.05, **_p_≤0.01, ***_p_≤0.001 vs control, t test

IFN-γ potentiates ER stress induced cell death

To test whether IFN-γ indeed aggravates ER stress-induced death, we preincubated INS-1E cells for 24 h with IFN-γ before exposing them to different concentrations of CPA (Fig. 2a). To assess the specificity of the putative effects of IFN-γ, cells were also precultured with IL-1β or CPA (Fig. 2b,c). CPA induced apoptosis in INS-1E cells in a dose-dependent manner. IFN-γ treatment alone led to a modest increase in apoptosis in INS-1E cells (apoptotic index 5.7±1, Fig. 2a). Pretreatment with IFN-γ potentiated CPA-induced apoptosis in INS-1E cells, increasing by 150 and 230% the apoptosis induced by 25 and 6.25 μmol/l of CPA, respectively (Fig. 2a). These joint effects were clearly higher than the sum of the isolated effects of IFN-γ and CPA. IFN-γ also potentiated the pro-apoptotic effects of CPA in FACS-purified rat beta cells. Thus, 24 h incubation of primary beta cells with 25 μmol/l CPA significantly induced apoptosis (apoptotic index of 7.8±1.3, _n_=6). This was increased by 175% after IFN-γ pretreatment (16.1±2.2; p<0.01 vs CPA alone, t test, _n_=6). IFN-γ alone did not induce apoptosis in primary cells (data not shown). The main mode of cell death observed in the experiments described above was apoptosis in both INS-1E cells and primary beta cells. The percentages of apoptosis observed for INS-1E cells and primary beta cells in the control conditions were 3.0±0.2 and 6.9±1.3, respectively. CPA did not induce NO production either alone or in combination with IFN-γ (data not shown). In contrast to the observations with IFN-γ, neither preincubation with IL-1β nor CPA potentiated CPA-induced apoptosis (Fig. 2b,c) or necrosis in INS-1E cells (data not shown). In these cases, only an additive effect was observed between the different treatments.

Fig. 2

IFN-γ, but not IL-1β or CPA, potentiates ER stress-induced cell death in INS-1E cells. INS-1E cells were pretreated (filled/shaded bars) or not (empty bars) with IFN-γ (0.036 μg/ml) (a) or IL-1β (10 U/ml) (b) for 24 h or CPA (6.25 μmol/l) (c) for 6 h. The cells were then exposed to 3.1, 6.25 or 25 μmol/l CPA or control (Ctrl, DMSO, 0.25%) for 15 h. Cell viability was determined with the DNA dyes Hoechst 342 and propidium iodide and apoptotic indexes were calculated as described in Materials and methods. Results are means±SEM of six to eight experiments. ***_p_≤0.001 vs condition without pre-treatment, ANOVA and t test with Bonferroni correction

IFN-γ decreases the expression of ER chaperones and a component of the ERAD pathway

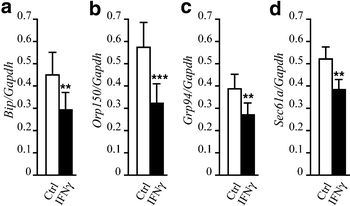

Exposure of INS-1E cells to IFN-γ for 30–36 h caused a significant decrease of the mRNAs encoding for Bip (Fig. 3a), Orp150 (Fig. 3b), Grp94 (Fig. 3c) and Sec61a (Fig. 3d). This inhibitory effect of IFN-γ, however, did not impair the induction of these genes by 6–12 h exposure to CPA (6.25–25 μmol/l; data not shown). IFN-γ did not inhibit calbindin or calreticulin mRNA expression under experimental conditions similar to those described in Fig. 3 (data not shown).

Fig. 3

IFN-γ downregulates mRNAs for ER chaperones and Sec61a. INS-1E cells were exposed for 30–36 h to IFN-γ (0.036 μg/ml); mRNA was then extracted and real-time RT-PCR was performed using specific primers for Bip (a), Orp150 (b), Grp94 (c) and Sec61a (d). Values of the gene of interest were corrected for Gapdh expression. The results are the means±SEM of six experiments. **_p_≤0.01,***_p_≤0.001 vs control, t test

IFN-γ decreases UPR responses and increases the expression of the pro-apoptotic gene Chop in beta cells

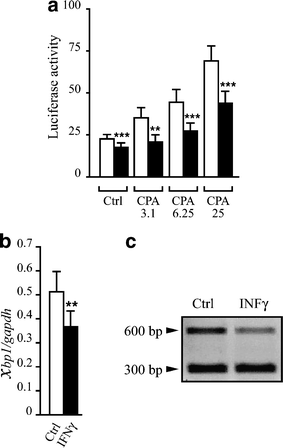

The results described above suggest that IFN-γ decreases key chaperones involved in the UPR. To evaluate the functional impact of IFN-γ on the UPR activation we used the UPRE reporter construct. This element was initially identified as a binding site for the transcription factor ATF6 [20], but later studies indicated that it is mostly activated by XBP1 [21]. Basal activity of the UPRE reporter in INS-1E cells was decreased by IFN-γ exposure (22%; Fig. 4a), and pretreatment with IFN-γ hampered activation of the UPRE reporter by different concentrations of CPA (around 40% inhibition; Fig. 4a). We then examined the effects of IFN-γ on total Xbp1 mRNA expression and observed a 30% decrease of the Xbp1 transcript in comparison to control (Fig. 4b). Since only spliced Xbp1 mRNA is translated to an active XBP1 protein, we next determined the levels of spliced Xbp1 mRNA in the presence or absence of IFN-γ. Between 30 and 36 h exposure to IFN-γ decreased _Xbp1_s mRNA (32.5±1.6% in control conditions vs 25.4±2.4% IFN-γ exposure, p<0.002; Fig. 4c). On the other hand, CPA (6.25 and 25 μmol/l) induction of both total Xbp1 and _Xbp1_s mRNAs was unaffected by the IFN-γ treatment (data not shown).

Fig. 4

IFN-γ decreases UPR responses in INS-1E cells. a INS-1E cells were co-transfected with the luciferase reporter construct containing five copies of the UPRE and the internal control pRL-CMV. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were pretreated (black bars) or not (empty bars) for 24 h with IFN-γ and then incubated with CPA (3.1, 6.25 or 25 μmol/l) or control (Ctrl, DMSO 0.25%) for 15 h. Results are the mean of nine experiments normalised for Renilla luciferase activity±SEM. **_p_≤0.01, ***_p_≤0.001 vs no pretreatment, t test. b INS-1E cells were treated for 30–36 h with IFN-γ or control as described in the Materials and methods. mRNA was then extracted and real-time RT-PCR was performed using specific primers for Xbp1 and values were corrected for Gapdh expression. Results are mean±SEM of six experiments. **_p_≤0.01 vs control, t test. c Cells were exposed to IFN-γ as described above (b). Xbp1 splicing was then assessed as described in Fig. 1. The picture is representative of six experiments

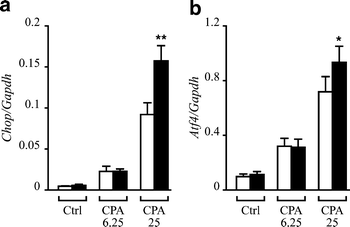

One of the mechanisms by which ER stress induces apoptosis is via Chop activation [22–24]. Thus, and because pretreatment with IFN-γ would decrease the ability of beta cells to face an ER stress, sequential treatment with IFN-γ and CPA would be expected to trigger a higher expression of Chop mRNA as compared to CPA alone. This was indeed the case, at least for the higher concentration of CPA tested. Thus, the induction of IFN-γ+CPA (25 μmol/l) on Chop mRNA expression was almost double the sum of the individual effects of IFN-γ and CPA on this mRNA (Fig. 5a). Induction of Chop by ER stress is abolished in cells that are knockout for the transcription factor ATF4 [25] and ATF4 has been shown to bind to the Chop promoter [26]; we therefore examined whether CPA induced Atf4 mRNA and whether IFN-γ preculture modified the expression of this transcription factor. As observed in Fig. 5b, CPA induces Atf4 mRNA, and pretreatment with IFN-γ augmented Atf4 induction by 25 μmol/l CPA.

Fig. 5

IFN-γ potentiates CPA induction of Chop and Atf4 mRNAs. INS-1E cells were pretreated (black bars) or not (empty bars) for 24 h with IFN-γ and then incubated with CPA (6.25 or 25 μmol/l) or control (Ctrl, DMSO 0.25%) for 15 h. mRNA was then extracted and real-time RT-PCR performed using specific primers for Chop (a) and Atf4 (b). Values were corrected for GAPDH expression. The results are the means±SEM of six experiments. ★ _p_≤0.05, ★★ _p_≤0.01 vs no pre-treatment, t test

Discussion

We have observed that low concentrations of CPA induce ER stress and UPR activation in INS-1E cells, as indicated by IRE-1-mediated Xbp1 alternative splicing, induction of a reporter construct containing five copies of the UPRE, and upregulation of mRNAs encoding classical markers of UPR activation such as Bip, Xbp1 and Chop. CPA induces a ‘pure’ ER stress by direct inhibition of the SERCA pump [27], depleting ER Ca2+ stores without inducing NO production (data not shown). Against this background, we used CPA here to study the putative potentiating effects of IFN-γ on ER stress. The results obtained indicate that IFN-γ potentiates CPA-induced apoptosis in INS-1E cells and in primary rat beta cells. In contrast, IL-1β or CPA has only a mild additive effect on CPA-induced cell death, indicating specificity for IFN-γ in this effect. In some cell types, induction of a mild ER stress protects against cell death by a subsequent and more severe ER stress-inducing stimulus [28–30]. This protection is mediated via induction of ER chaperones such as BiP, GRP 94 and calreticulin [28–30]. The lack of such a phenomenon in beta cells exposed to sublethal concentrations of CPA or IL-1β (present data) probably reflects the exquisite vulnerability of beta cells to disruption of ER homeostasis.

Prolonged exposure to IFN-γ significantly decreased UPRs, as suggested by the decreased basal _xbp1_s mRNA and the decrease in both basal and CPA-induced activity of the UPRE reporter construct. Moreover, mRNA expression of important ER chaperones, such as Orp150, Grp94 and Bip, and of the α subunit of the Sec61 translocon, were also decreased by IFN-γ. XBP1 is a key transcription factor for the induction of ER chaperones, including genes from the ERAD pathway during UPR [5, 31]. The spliced (active) form of Xbp1 mRNA is detectable at basal levels in primary beta cells [8] and in INS-1E cells (present study). Taking into account the high synthesis of insulin by beta cells, this basal XBP1 activation is probably important for the maintenance of beta cell ER homeostasis. BiP is a master regulator of ER functions, directing protein folding and assembly, sensing stress in the organelle and contributing to the preservation of the ER Ca2+ stores [32]. GRP94 also has Ca2+-binding properties [33]. The high basal levels of BiP and ORP150 expression in beta cells suggest an important role for these chaperones in beta cell function and survival [24, 34]. All these chaperones, presently shown to be downregulated by IFN-γ, have been previously shown to protect different cell types against death [29, 35–38]. The SEC61 channel is involved both in translation of ER proteins and translocation of proteins to be degraded by the ERAD pathway [39, 40]. Efficient removal of misfolded proteins via the ERAD pathway is essential for cellular recovery during the ER stress response [40]. The lower basal expression of Xbp1, Bip, Grp94, Orp150 and Sec61a mRNAs induced by IFN-γ probably decreases the beta cells defences against ER stress, rendering them particularly vulnerable to agents such as IL-1β or CPA. This is in agreement with the potentiating effects of IFN-γ on the subsequent CPA-induced ER stress response, as measured by increased Chop expression and apoptosis (present findings), and with recent observations that IFN-γ contributes to ER stress and apoptosis in oligodentrocytes [41]. Atf4 mRNA expression was upregulated by CPA and pre-culture with IFN-γ led to a small but significant increase in CPA-mediated Atf4 induction. This may contribute to the potentiating effects of IFN-γ on Chop mRNA expression, because ATF4 is involved in Chop induction during ER stress [26]. Further studies are now necessary to understand the molecular mechanisms by which IFN-γ modulates the expression of this group of genes.

Of note, IFN-γ stimulates MHC class I and II expression and induction of transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) genes in beta cells [12, 42]. The MHC class I complex is assembled in the ER, while antigenic peptides generated in the cytosol are transported to the ER via the TAP transporters. Part of these peptides return to the cytosol, via the SEC61 channel [43]. The accumulation of MHC molecules and peptides in the ER lumen leads to an ER overload that, under certain conditions, may cause ER stress [43]. In line with this, transgenic overexpression of MHC molecules in the beta cells leads to severe beta cell dysfunction and death [44–46]. It is thus possible that IFN-γ-mediated ER overload also contributes to the potentiating effects of IFN-γ on ER stress-induced beta cell apoptosis.

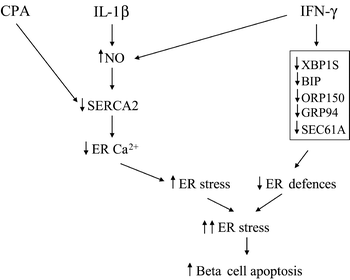

We previously observed that IL-1β induces an ER stress response in beta cells without leading to apoptosis [8]. IFN-γ alone did not induce ER stress [8] (present data) but, in combination with IL-1β, it increased IL-1β-induced Ca2+ depletion and triggered beta cell apoptosis [8]. Based on the present observations, we propose a model to explain the synergistic effects of the two cytokines on beta cell ER stress and apoptosis (Fig. 6). Thus, IL-1β induces an NO-mediated inhibition of the SERCA2 pump and a partial depletion of ER Ca2+ stores, leading to ER stress in beta cells. CPA also inhibits SERCA activity and causes ER stress, but this effect is independent of NO formation. IFN-γ enhances IL-1β-induced ER stress by downregulating beta cell defences against ER stress and by increasing NO production. These combined effects, if sufficiently prolonged, will eventually ‘convince’ the beta cells to start the apoptotic programme.

Fig. 6

Proposed model for the synergistic effects of IL-1β or CPA and IFN-γ in inducing beta cell ER stress and apoptosis. Details, see Discussion

References

- Harding HP, Zeng H, Zhang Y et al (2001) Diabetes mellitus and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in perk−/− mice reveals a role for translational control in secretory cell survival. Mol Cell 7:1153–1163

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Scheuner D, Mierde DV, Song B et al (2005) Control of mRNA translation preserves endoplasmic reticulum function in beta cells and maintains glucose homeostasis. Nat Med 11:757–764

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Ladiges WC, Knoblaugh SE, Morton JF et al (2005) Pancreatic β-cell failure and diabetes in mice with a deletion mutation of the endoplasmic reticulum molecular chaperone gene P58IPK. Diabetes 54:1074–1081

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Ma Y, Hendershot LM (2004) ER chaperone functions during normal and stress conditions. J Chem Neuroanat 28:51–65

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Rutkowski DT, Kaufman RJ (2004) A trip to the ER: coping with stress. Trends Cell Biol 14:20–28

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Xu C, Bailly-Maitre B, Reed JC (2005) Endoplasmic reticulum stress: cell life and death decisions. J Clin Invest 115:2656–2664

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Eizirik DL, Mandrup-Poulsen T (2001) A choice of death—the signal-transduction of immune-mediated beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetologia 44:2115–2133

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Cardozo AK, Ortis F, Storling J et al (2005) Cytokines downregulate the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum pump Ca2+ ATPase 2b and deplete endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+, leading to induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes 54:452–461

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Rasschaert J, Liu D, Kutlu B et al (2003) Global profiling of double stranded RNA- and IFN-γ-induced genes in rat pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 46:1641–1657

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kutlu B, Cardozo AK, Darville MI et al (2003) Discovery of gene networks regulating cytokine-induced dysfunction and apoptosis in insulin-producing INS-1 cells. Diabetes 52:2701–2719

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Rasschaert J, Ladriere L, Urbain M et al (2005) Toll-like receptor 3 and STAT-1 contribute to double-stranded RNA+ interferon-γ-induced apoptosis in primary pancreatic β-cells. J Biol Chem 280:33984–33991

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Cardozo AK, Kruhoffer M, Leeman R, Orntoft T, Eizirik DL (2001) Identification of novel cytokine-induced genes in pancreatic β-cells by high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Diabetes 50:909–920

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kharroubi I, Rasschaert J, Eizirik DL, Cnop M (2003) Expression of adiponectin receptors in pancreatic β cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 312:1118–1122

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Cardozo AK, Proost P, Gysemans C, Chen MC, Mathieu C, Eizirik DL (2003) IL-1β and IFN-γ induce the expression of diverse chemokines and IL-15 in human and rat pancreatic islet cells, and in islets from pre-diabetic NOD mice. Diabetologia 46:255–266

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Calfon M, Zeng H, Urano F et al (2002) IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature 415:92–96

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Paschen W, Hotop S, Aufenberg C (2003) Loading neurons with BAPTA-AM activates xbp1 processing indicative of induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Calcium 33:83–89

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Hoorens A, Van de Casteele M, Kloppel G, Pipeleers D (1996) Glucose promotes survival of rat pancreatic beta cells by activating synthesis of proteins which suppress a constitutive apoptotic program. J Clin Invest 98:1568–1574

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Liu D, Darville M, Eizirik DL (2001) Double-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) induces β-cell Fas messenger RNA expression and increases cytokine-induced β-cell apoptosis. Endocrinology 142:2593–2599

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Darville MI, Eizirik DL (1998) Regulation by cytokines of the inducible nitric oxide synthase promoter in insulin-producing cells. Diabetologia 41:1101–1108

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Wang Y, Shen J, Arenzana N, Tirasophon W, Kaufman RJ, Prywes R (2000) Activation of ATF6 and an ATF6 DNA binding site by the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J Biol Chem 275:27013–27020

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K (2001) XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell 107:881–891

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Oyadomari S, Koizumi A, Takeda K et al (2002) Targeted disruption of the Chop gene delays endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated diabetes. J Clin Invest 109:525–532

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Oyadomari S, Mori M (2004) Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ 11:381–389

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Oyadomari S, Takeda K, Takiguchi M et al (2001) Nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in pancreatic β cells is mediated by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:10845–10850

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Harding HP, Zhang Y, Zeng H et al (2003) An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell 11:619–633

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Ma Y, Brewer JW, Diehl JA, Hendershot LM (2002) Two distinct stress signaling pathways converge upon the CHOP promoter during the mammalian unfolded protein response. J Mol Biol 318:1351–1365

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Inesi G, Sagara Y (1994) Specific inhibitors of intracellular Ca2+ transport ATPases. J Membr Biol 141:1–6

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Liu H, Miller E, van de Water B, Stevens JL (1998) Endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins block oxidant-induced Ca2+ increases and cell death. J Biol Chem 273:12858–12862

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Liu H, Bowes RC 3rd, van de Water B, Sillence C, Nagelkerke JF, Stevens JL (1997) Endoplasmic reticulum chaperones GRP78 and calreticulin prevent oxidative stress, Ca2+ disturbances, and cell death in renal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 272:21751–21759

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Bedard K, MacDonald N, Collins J, Cribb A (2004) Cytoprotection following endoplasmic reticulum stress protein induction in continuous cell lines. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 94:124–131

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH (2003) XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol 23:7448–7459

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Hendershot LM (2004) The ER function BiP is a master regulator of ER function. Mt Sinai J Med 71:289–297

PubMed Google Scholar - Koch G, Smith M, Macer D, Webster P, Mortara R (1986) Endoplasmic reticulum contains a common, abundant calcium-binding glycoprotein, endoplasmin. J Cell Sci 86:217–232

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kobayashi T, Ogawa S, Yura T, Yanagi H (2000) Abundant expression of 150-kDa oxygen-regulated protein in mouse pancreatic β cells is correlated with insulin secretion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 267:831–837

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Rao RV, Peel A, Logvinova A et al (2002) Coupling endoplasmic reticulum stress to the cell death program: role of the ER chaperone GRP78. FEBS Lett 514:122–128

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kitao Y, Ozawa K, Miyazaki M et al (2001) Expression of the endoplasmic reticulum molecular chaperone (ORP150) rescues hippocampal neurons from glutamate toxicity. J Clin Invest 108:1439–1450

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kitano H, Nishimura H, Tachibana H, Yoshikawa H, Matsuyama T (2004) ORP150 ameliorates ischemia/reperfusion injury from middle cerebral artery occlusion in mouse brain. Brain Res 1015:122–128

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Bando Y, Katayama T, Aleshin AN, Manabe T, Tohyama M (2004) GRP94 reduces cell death in SH-SY5Y cells perturbated calcium homeostasis. Apoptosis 9:501–508

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kalies KU, Allan S, Sergeyenko T, Kroger H, Romisch K (2005) The protein translocation channel binds proteasomes to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. EMBO J 24:2284–2293

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Romisch K (2005) Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 21:435–456

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Lin W, Harding HP, Ron D, Popko B (2005) Endoplasmic reticulum stress modulates the response of myelinating oligodendrocytes to the immune cytokine interferon-γ. J Cell Biol 169:603–612

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Pavlovic D, van de Winkel M, van der Auwera B et al (1997) Effect of interferon-γ and glucose on major histocompatibility complex class I and class II expression by pancreatic β- and non-β-cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:2329–2336

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Romisch K (1999) Surfing the Sec61 channel: bidirectional protein translocation across the ER membrane. J Cell Sci 112(Pt 23):4185–4191

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Sarvetnick N, Liggitt D, Pitts SL, Hansen SE, Stewart TA (1988) Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus induced in transgenic mice by ectopic expression of class II MHC and interferon-γ. Cell 52:773–782

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Grodsky GM, Ma YH, Cullen B, Sarvetnick N (1992) Effect on insulin production sorting and secretion by major histocompatibility complex class II gene expression in the pancreatic β-cell of transgenic mice. Endocrinology 131:933–938

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Allison J, Campbell IL, Morahan G, Mandel TE, Harrison LC, Miller JF (1988) Diabetes in transgenic mice resulting from over-expression of class I histocompatibility molecules in pancreatic beta cells. Nature 333:529–533

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar