Comparison between a tubeless, on-body automated insulin delivery system and a tubeless, on-body sensor-augmented pump in type 1 diabetes: a multicentre randomised controlled trial (original) (raw)

Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

This study compares the efficacy and safety of a tubeless, on-body automated insulin delivery (AID) system with that of a tubeless, on-body sensor-augmented pump (SAP).

Methods

This multicentre, parallel-group, RCT was conducted at 13 tertiary medical centres in South Korea. Adults aged 19–69 years with type 1 diabetes who had HbA1c levels of <85.8 mmol/mol (<10.0%) were eligible. The participants were assigned at a 1:1 ratio to receive a tubeless, on-body AID system (intervention group) or a tubeless, on-body SAP (control group) for 12 weeks. Stratified block randomisation was conducted by an independent statistician. Blinding was not possible due to the nature of the intervention. The primary outcome was the percentage of time in range (TIR), blood glucose between 3.9 and 10.0 mmol/l, as measured by continuous glucose monitoring. ANCOVAs were conducted with baseline values and study centres as covariates.

Results

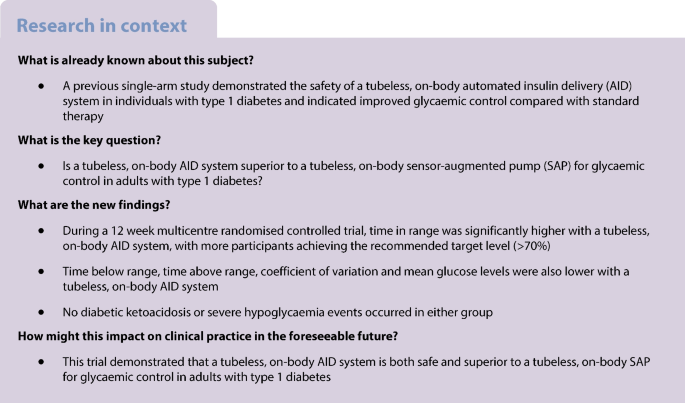

A total of 104 participants underwent randomisation, with 53 in the intervention group and 51 in the control group. The mean (±SD) age of the participants was 40±11 years. The mean (±SD) TIR increased from 62.1±17.1% at baseline to 71.5±10.7% over the 12 week trial period in the intervention group and from 64.7±17.0% to 66.9±15.0% in the control group (difference between the adjusted means: 6.5% [95% CI 3.6%, 9.4%], p<0.001). Time below range, time above range, CV and mean glucose levels were also significantly better in the intervention group compared with the control group. HbA1c decreased from 50.9±9.9 mmol/mol (6.8±0.9%) at baseline to 45.9±7.4 mmol/mol (6.4±0.7%) after 12 weeks in the intervention group and from 48.7±9.1 mmol/mol (6.6±0.8%) to 45.7±7.5 mmol/mol (6.3±0.7%) in the control group (difference between the adjusted means: −0.7 mmol/mol [95% CI −2.0, 0.8 mmol/mol] (−0.1% [95% CI −0.2%, 0.1%]), _p_=0.366). No diabetic ketoacidosis or severe hypoglycaemia events occurred in either group.

Conclusions/interpretation

The use of a tubeless, on-body AID system was safe and associated with superior glycaemic profiles, including TIR, time below range, time above range and CV, than the use of a tubeless, on-body SAP.

Trial registration

Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS) KCT0008398

Funding

The study was funded by a grant from the Korea Medical Device Development Fund supported by the Ministry of Science and ICT; the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy; the Ministry of Health and Welfare; and the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (grant number: RS-2020-KD000056).

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glycaemic control for individuals with type 1 diabetes is challenging. Due to the impaired insulin secretory function of individuals with type 1 diabetes, they often experience hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia [[1](#ref-CR1 "Steele C, Hagopian WA, Gitelman S et al (2004) Insulin secretion in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 53(2):426–433. https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.53.2.426

"),[2](#ref-CR2 "Cryer PE (2010) Hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 39(3):641–654.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2010.05.003

"),[3](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR3 "Maia FFR, Araújo LR (2007) Efficacy of continuous glucose monitoring system (CGMS) to detect postprandial hyperglycemia and unrecognized hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 75(1):30–34.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2006.05.009

")\]. Real-world data show that a substantial number of individuals with type 1 diabetes do not meet glycaemic control targets in current guidelines \[[4](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR4 "Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM et al (2019) State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016–2018. Diabetes Technol Ther 21(2):66–72.

https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2018.0384

")\].An automated insulin delivery (AID) system integrates an insulin pump with data from continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), with a control algorithm that automatically determines the rate of insulin delivery. Considering the glycaemic and psychosocial benefits substantiated by multiple RCTs and real-world data, current international guidelines recommend that AID systems be offered to all individuals with type 1 diabetes who are capable of using the device safely [[5](#ref-CR5 "Sherr JL, Heinemann L, Fleming GA et al (2023) Automated insulin delivery: benefits, challenges, and recommendations. A Consensus Report of the Joint Diabetes Technology Working Group of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetologia 66(1):3–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-022-05744-z

"),[6](#ref-CR6 "Moser O, Riddell MC, Eckstein ML et al (2020) Glucose management for exercise using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and intermittently scanned CGM (isCGM) systems in type 1 diabetes: position statement of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and of the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) endorsed by JDRF and supported by the American Diabetes Association (ADA). Diabetologia 63(12):2501–2520.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05263-9

"),[7](#ref-CR7 "Holt RIG, DeVries JH, Hess-Fischl A et al (2021) The management of type 1 diabetes in adults. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia 64(12):2609–2652.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05568-3

"),[8](#ref-CR8 "ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR et al (2023) 7. Diabetes technology: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 46(Suppl 1):S111–S127.

https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-S007

"),[9](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR9 "Hur KY, Moon MK, Park JS et al (2021) 2021 Clinical practice guidelines for diabetes mellitus of the Korean Diabetes Association. Diabetes Metab J 45(4):461–481.

https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2021.0156

")\].The use of a disposable tubeless patch pump is another important area of innovation. We previously explored the safety of a tubeless, on-body sensor-augmented pump (SAP), the EOPatch M (EOFLOW, Seongnam, Republic of Korea), in a 4 week, two-centre, single-arm trial [[10](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR10 "Park J, Park N, Han S et al (2022) A 4-week, two-center, open-label, single-arm study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of EOPatch in well-controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab J 46(6):941–947. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2021.0299

")\]. Recently, a single-arm clinical trial of the first tubeless, on-body AID system with customisable glycaemic targets demonstrated its safety and showed significantly improved HbA1c levels and time in range (TIR) for target glucose from the baseline standard therapy, with a very low occurrence of hypoglycaemia \[[11](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR11 "Brown SA, Forlenza GP, Bode BW et al (2021) Multicenter trial of a tubeless, on-body automated insulin delivery system with customizable glycemic targets in pediatric and adult participants with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 44(7):1630–1640.

https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-0172

")\].This multicentre RCT compared the efficacy and safety of a tubeless, on-body AID system with that of a tubeless, on-body SAP for glycaemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes.

Methods

Study design and participants

This prospective, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre RCT was conducted at 13 tertiary medical centres in South Korea. The trial is registered at the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS) (registration no. KCT0008398), and the trial protocol is provided in the electronic supplementary material (ESM) Methods. This study was approved by the institutional review board of each centre and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

Adults aged 19–69 years who had received a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes at least 1 year before enrolment, had been treated with multiple daily insulin injections (MDI) or insulin pumps for at least 3 months and had HbA1c levels of <85.8 mmol/mol (<10.0%) were eligible. According to the current reimbursement criteria of the Korean National Health Insurance Service, type 1 diabetes can be diagnosed in insulin users who meet at least one of the following criteria: fasting C-peptide ≤0.2 nmol/l; glucagon- or meal-stimulated C-peptide ≤0.6 nmol/l; positive for glutamic acid decarboxylase or other autoantibodies; 24 h urine C-peptide <30 µg/day; or a history of diabetic ketoacidosis at the time of diabetes diagnosis [[12](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR12 "Baek JH, Lee WJ, Lee BW et al (2021) Age at diagnosis and the risk of diabetic nephropathy in young patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab J 45(1):46–54. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2019.0134

")\]. Key exclusion criteria included experiencing diabetic ketoacidosis or severe hypoglycaemia requiring hospitalisation or emergent treatment in the preceding 12 weeks, as well as pregnancy. Complete eligibility criteria are provided in the ESM [Methods](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#MOESM1). The enrolled participants were considered to represent the target trial population in terms of sex and age. Sex was not considered in the study design.After informed consent was provided, age, sex (determined through self-reported information), race and medical history including any pre-existing conditions and medication usage were investigated. Physical examination and laboratory tests were also conducted. Eligible participants underwent run-in phase 1, during which they used a Dexcom G6 (Dexcom, San Diego, CA, USA) for 2 weeks. If the sensor wear time was ≥70% and no severe hypoglycaemia event occurred, the participants underwent run-in phase 2, during which they used the on-body SAP (EOPatch M) with Dexcom G6 for 2 weeks. The duration of the run-in phase depended on whether the participant had previously used CGM or an on-body SAP. Details are provided in the ESM Methods.

After completion of the run-in phase, eligible participants were randomised at a 1:1 ratio to the intervention group (tubeless, on-body AID system; EOPatch X [EOFLOW, Seongnam, Republic of Korea]) or the control group (tubeless, on-body SAP; EOPatch M) by an interactive web response system. EOPatch X, a descendant of EOPatch M, is a smartphone app-based hybrid closed-loop AID system using TypeZero’s inControl closed-loop algorithms (TypeZero Technologies, Charlottesville, VA, USA). Stratified block randomisation was conducted using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) by an independent statistician unrelated to this study. Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding was not possible.

Following randomisation, the participants wore patch pumps and Dexcom G6 for 12 weeks. HbA1c and treatment satisfaction, estimated using the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ) [[13](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR13 "Bradley C, Gamsu DS (1994) Guidelines for encouraging psychological well-being: report of a Working Group of the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe and International Diabetes Federation European Region St Vincent Declaration Action Programme for Diabetes. Diabet Med 11(5):510–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.1994.tb00316.x

")\] and Insulin Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (ITSQ) \[[14](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR14 "Anderson RT, Skovlund SE, Marrero D et al (2004) Development and validation of the insulin treatment satisfaction questionnaire. Clin Ther 26(4):565–578.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90059-8

")\], were measured at baseline and week 12\. The DTSQ change version (DTSQc) \[[15](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR15 "Bradley C (1999) Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire. Change version for use alongside status version provides appropriate solution where ceiling effects occur. Diabetes Care 22(3):530–532.

https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.22.3.530

")\] was assessed at week 12\. HbA1c was measured at each study centre using National Glycohemoglobin Standardisation Program-certified methods.Study outcomes

The primary outcome was the percentage of TIR (3.9–10.0 mmol/l) during the 12 weeks of the trial. The secondary outcomes included the percentage of time above range (TAR) at >10.0 mmol/l during the 12 weeks; the percentage of TAR >13.9 mmol/l during the 12 weeks; the percentage of time below range (TBR) at <3.9 mmol/l during the 12 weeks; the percentage of TBR at <3.0 mmol/l during the 12 weeks; the mean glucose level during the 12 weeks; the CV during the 12 weeks; and the HbA1c level at week 12. Additional analyses were done according to the time of day and the time spent in artificial pancreas (AP) mode (closed-loop mode). Other secondary outcomes included the treatment satisfaction measured by the DTSQ, DTSQc and ITSQ and the total daily insulin dose delivered during the 12 week trial period. The safety outcomes were all adverse events, including the occurrence of diabetic ketoacidosis and severe hypoglycaemia.

Statistical analysis

We calculated that a sample size of 44 per group was necessary to provide at least 85% power in demonstrating the superiority of the tubeless, on-body AID system over the on-body SAP, assuming a difference in TIR of 9%, SD of 14% and a significance level of 5%, based on the previous trial [[16](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR16 "Brown SA, Kovatchev BP, Raghinaru D et al (2019) Six-month randomized, multicenter trial of closed-loop control in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 381(18):1707–1717. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1907863

")\]. The sample size was set at 52 per group to accommodate a 15% potential loss to follow-up. Therefore, we planned to enrol a total of 104 participants.Analyses followed the intention-to-treat principle. Missing values in the CGM metrics and insulin dose data were imputed using multiple imputations. Other analyses used only the available data.

For the analyses of CGM metrics and HbA1c, including primary outcome analyses, ANCOVAs were conducted with baseline values and study centres as covariates. Additionally, we analysed the percentage of individuals with TIR >70% in each group using Pearson’s χ2 test, although it was not included in the initial statistical analysis plan. For other secondary analyses, between-group differences were compared using Student’s t test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Within-group differences in the DTSQ and ITSQ at baseline and week 12 were compared using paired t test or the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4).

Results

Study participants

The study was conducted from 27 April 2022 to 30 November 2022 at 13 medical centres in South Korea. A total of 112 individuals were screened, and 105 underwent the run-in phase. Among 105 participants, one person did not progress to randomisation due to withdrawal of consent. Consequently, 104 participants were randomised (53 to the intervention group and 51 to the control group) and 97 participants (50 in the intervention group and 47 in the control group) completed the trial. ESM Fig. 1 presents the flow chart of study participation.

The baseline characteristics of participants were balanced between groups (Table 1). Their mean age was 40±11 years, and 38/104 (36.5%) were male. The mean duration of diabetes was 13±10 years, and 12/104 (11.5%) were insulin pump users. None of the participants used an AID system, while 77/104 (74.0%) used CGM before the trial. The mean HbA1c level was 49.7±9.5 mmol/mol (6.7±0.9%), and the fasting C-peptide level was 0.05±0.09 nmol/l.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of study participants

TIR

Table 2 presents the TIR during the trial period. The mean (±SD) TIR increased from 62.1±17.1% at baseline to 71.5±10.7% over the 12 week trial period in the intervention group and from 64.7±17.0% to 66.9±15.0% in the control group (difference between the adjusted means: 6.5% [95% CI 3.6%, 9.4%], p<0.001). The intervention group had a higher proportion of individuals achieving TIR >70% compared with the control group (33/53 [62.3%] vs 21/51 [41.2%], _p_=0.031).

Table 2 Primary and secondary outcomes: CGM metrics and HbA1c level

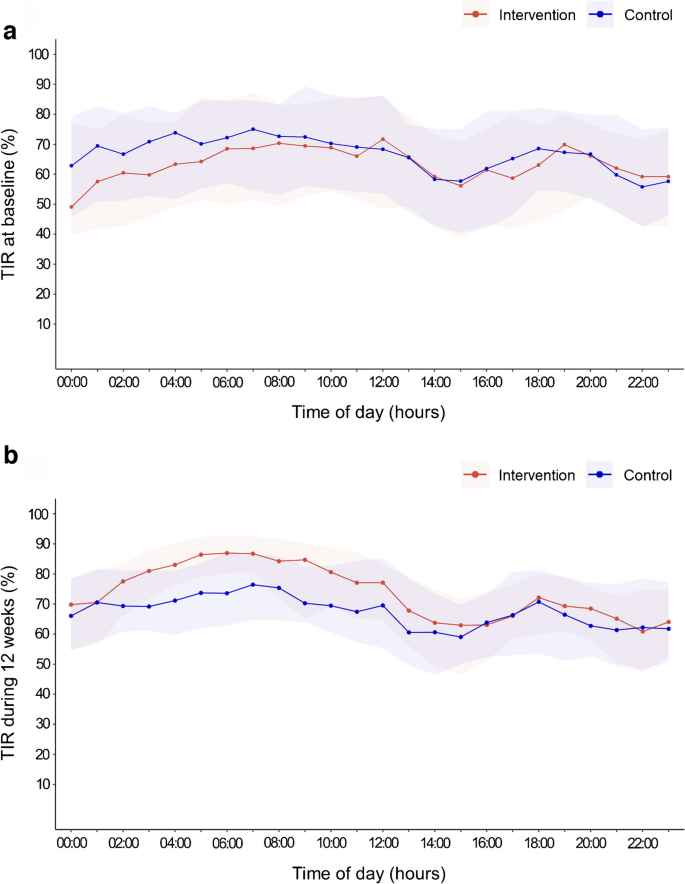

Figure 1 shows the percentage of TIR according to the time of day throughout the 12 weeks. The improvement in TIR in the intervention group was primarily driven by overnight improvement. The difference between the adjusted means in TIR during the daytime (06:00 hours to 23:59 hours) was 5.3% [95% CI 2.4%, 8.2%], and the difference during the night-time (00:00 hours to 05:59 hours) was 9.7% [95% CI 5.7%, 13.7%] (ESM Table 1).

Fig. 1

Percentage of TIR (3.9–10.0 mmol/l) according to the time of day throughout the 12 week trial period. (a) Percentage of TIR at baseline; (b) percentage of TIR during 12 weeks. Datapoints are the median values across participants in each group, and the shaded regions represent the interquartile range

Other CGM metrics and HbA1c

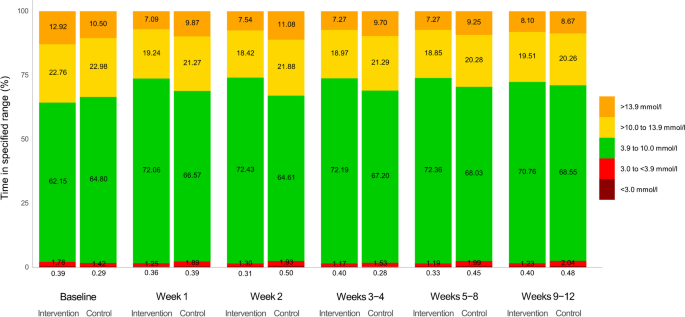

During the 12 week trial, the intervention group presented lower TAR >10.0 mmol/l (difference between the adjusted means: −5.5% [95% CI −8.5%, −2.4%], p<0.001) and TAR >13.9 mmol/l (difference between the adjusted means: −3.6% [95% CI −5.7%, −1.5%], _p_=0.001) than the control group (Table 2). The change in CGM metrics was evident from the first week and consistent throughout the 12 week trial period (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

Change in CGM metrics during the study period. Percentages of time in specified range (TAR level 2, >13.9 mmol/l; TAR level 1, >10.0 to 13.9 mmol/l; TIR, 3.9 to 10.0 mmol/l; TBR level 1, 3.0 to <3.9 mmol/l; and TBR level 2, <3.0 mmol/l) during specific study periods are presented

The higher TIR of the intervention group was achieved with a lower TBR (Table 2). The intervention group presented a lower TBR <3.9 mmol/l than the control group (difference between the adjusted means: −1.0% [95% CI −1.5%, −0.5%], p<0.001). TBR <3.0 mmol/l was similar between the groups; however, during the night, the intervention group exhibited lower TBR <3.0 mmol/l (difference between the adjusted means: −0.2% [95% CI −0.4%, −0.01%], _p_=0.038; ESM Table 1).

The mean glucose level was also lower in the intervention group than in the control group (Table 2), as was the CV. HbA1c decreased from 50.9±9.9 mmol/mol (6.8±0.9%) at baseline to 45.9±7.4 mmol/mol (6.4±0.7%) after 12 weeks in the intervention group and from 48.7±9.1 mmol/mol (6.6±0.8%) to 45.7±7.5 mmol/mol (6.3±0.7%) in the control group (difference between the adjusted means: −0.7 mmol/mol [95% CI −2.0, 0.8 mmol/mol] (−0.1% [95% CI −0.2%, 0.1%]), _p_=0.366).

Use of AP mode

The mean percentage of time spent wearing the patch pump was 98.4±2.5% (98.3±2.4% in the intervention group and 98.5±2.5% in the control group, _p_=0.101). For the intervention group, the mean percentage of time spent in AP mode was 79.8±12.3%. Participants who used AP mode >80% of the time had a TIR of 73.8±10.4%, whereas those using AP mode for ≤80% of the time had a TIR of 68.4±10.5% (difference between the adjusted means: 2.2% [95% CI −2.2%, 6.6%], _p_=0.321).

Other secondary outcomes

The total daily insulin dose delivered during the 12 week trial did not differ between groups (ESM Table 2).

Treatment satisfaction, estimated using the DTSQ, had increased significantly from baseline at week 12 in both the intervention group and the control group, but without a between-group difference (ESM Table 3). In both groups, ITSQ scores decreased significantly at week 12, indicating increased treatment satisfaction. At week 12, the intervention group had a lower ITSQ score than the control group.

Adverse events

Adverse events occurred in 14/53 (26.4%) individuals in the intervention group and 13/51 (25.5%) in the control group (Table 3). A serious adverse event, hospitalisation due to COVID-19, occurred in one participant in the control group. Neither diabetic ketoacidosis nor severe hypoglycaemia occurred in either group. Device-related adverse events, which were all skin or subcutaneous tissue disorders, occurred in 8/53 (15.1%) participants in the intervention group and 6/51 (11.8%) participants in the control group. The most common device-related adverse event was a rash (5/53 [9.4%] in the intervention group and 5/51 [9.8%] in the control group).

Table 3 Adverse events

Discussion

During our 12 week multicentre RCT, the use of the tubeless, on-body AID system was associated with greater improvement in glycaemic profiles than the use of the tubeless, on-body SAP. The AID system increased TIR more than the SAP without serious adverse events. TAR, TBR, mean glucose and CV were also improved more with the AID system than the SAP.

Despite advances in insulin pump technology [[5](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR5 "Sherr JL, Heinemann L, Fleming GA et al (2023) Automated insulin delivery: benefits, challenges, and recommendations. A Consensus Report of the Joint Diabetes Technology Working Group of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetologia 66(1):3–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-022-05744-z

"), [17](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR17 "Boughton CK, Hovorka R (2021) New closed-loop insulin systems. Diabetologia 64(5):1007–1015.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05391-w

"), [18](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR18 "Moon SJ, Jung I, Park CY (2021) Current advances of artificial pancreas systems: a comprehensive review of the clinical evidence. Diabetes Metab J 45(6):813–839.

https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2021.0177

")\], many individuals still do not use insulin pumps \[[4](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR4 "Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM et al (2019) State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016–2018. Diabetes Technol Ther 21(2):66–72.

https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2018.0384

"), [10](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR10 "Park J, Park N, Han S et al (2022) A 4-week, two-center, open-label, single-arm study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of EOPatch in well-controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab J 46(6):941–947.

https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2021.0299

")\]. An important factor contributing to patient reluctance to use pumps is discomfort with the tube of the insulin infusion set that delivers insulin from a pump to subcutaneous tissue \[[19](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR19 "Zhang JY, Shang T, Chattaraj S et al (2021) Advances in insulin pump infusion sets symposium report. J Diabetes Sci Technol 15(3):705–709.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1932296821999080

")\]. Issues associated with the insulin infusion set, aside from discomfort, include kinking, displacement or leakage of the cannula, a loose connection between the reservoir and cannula, reservoir leaks and occlusion \[[20](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR20 "Deiss D, Adolfsson P, Alkemade-van Zomeren M et al (2016) Insulin infusion set use: European perspectives and recommendations. Diabetes Technol Ther 18(9):517–524.

https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2016.07281.sf

"), [21](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR21 "Pickup JC, Yemane N, Brackenridge A, Pender S (2014) Nonmetabolic complications of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion: a patient survey. Diabetes Technol Ther 16(3):145–149.

https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2013.0192

")\]. Insulin infusion set failure is a major concern because it can cause serious adverse effects, including diabetic ketoacidosis. Tubeless patch pumps might reduce those problems by attaching directly to the skin \[[22](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR22 "Lebenthal Y, Lazar L, Benzaquen H, Shalitin S, Phillip M (2012) Patient perceptions of using the OmniPod system compared with conventional insulin pumps in young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 14(5):411–417.

https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2011.0228

")\].A tubeless, on-body AID system from another company was demonstrated to be safe and beneficial in terms of glycaemic control in a recent clinical trial [[11](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR11 "Brown SA, Forlenza GP, Bode BW et al (2021) Multicenter trial of a tubeless, on-body automated insulin delivery system with customizable glycemic targets in pediatric and adult participants with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 44(7):1630–1640. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-0172

")\]. However, that study employed a single-arm design, with standard therapy (usual insulin regimen) serving as the comparator. Our study has strengths including a multicentre RCT design using a comparator SAP. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first multicentre RCT comparing a tubeless, on-body AID system with a tubeless, on-body SAP.The AID system demonstrated glycaemic benefits from the first week, and the effect was consistent throughout the 12 week study period. The intervention group had a higher proportion of participants achieving the recommended TIR of >70% [[23](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR23 "ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR et al (2023) 6. Glycemic targets: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 46(Suppl 1):S97–S110. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-S006

"), [24](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR24 "Yu J, Lee SH, Kim MK (2022) Recent updates to clinical practice guidelines for diabetes mellitus. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 37(1):26–37.

https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2022.105

")\] compared with the control group (62.3% vs 41.2%, _p_\=0.031). The AID system increased TIR more than the SAP (difference between the adjusted means: 6.5%, _p_<0.001). Given that a 5% increase in TIR has been deemed clinically significant \[[5](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR5 "Sherr JL, Heinemann L, Fleming GA et al (2023) Automated insulin delivery: benefits, challenges, and recommendations. A Consensus Report of the Joint Diabetes Technology Working Group of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetologia 66(1):3–22.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-022-05744-z

"), [25](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR25 "Beck RW, Bergenstal RM, Cheng P et al (2019) The relationships between time in range, hyperglycemia metrics, and HbA1c. J Diabetes Sci Technol 13(4):614–626.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1932296818822496

")\], the additional improvement in TIR achieved with the tubeless, on-body AID system compared with the SAP is promising.A reduction in TAR was the main contributor to the improvement in TIR. With the AID system, TAR >10.0 mmol/l decreased by 5.5% more than with the SAP. Importantly, a reduction in TAR was achievable with a reduction in TBR. Even though the baseline TBR <3.9 mmol/l of the participants in both groups was low (1.9%), the AID system showed significant between-group differences (1.0%). CV was also lower with the AID system. Considering that the groups showed no significant differences in the total daily insulin dose delivered during the 12 week trial, it is likely that the AID system enabled participants to receive their insulin doses at optimal times. The benefits of the AID system were particularly pronounced at night, consistent with the results of other AID systems [[16](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR16 "Brown SA, Kovatchev BP, Raghinaru D et al (2019) Six-month randomized, multicenter trial of closed-loop control in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 381(18):1707–1717. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1907863

"), [26](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR26 "Wadwa RP, Reed ZW, Buckingham BA et al (2023) Trial of hybrid closed-loop control in young children with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 388(11):991–1001.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2210834

"), [27](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR27 "Breton MD, Kanapka LG, Beck RW et al (2020) A randomized trial of closed-loop control in children with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 383(9):836–845.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2004736

")\], as the meal bolus insulin was not automatically controlled in this hybrid closed-loop AID system.Although the AID system demonstrated better CGM metrics than the SAP, it failed to show superiority in HbA1c levels. The low baseline HbA1c levels (49.7 mmol/mol [6.7%]) of the participants might have contributed to that result. Despite their low baseline HbA1c levels, it is notable that HbA1c levels were reduced in both the intervention and control groups. Mean HbA1c was substantially lower than would be expected based on mean TIR, given that a mean HbA1c of 53 mmol/mol (7.0%) generally corresponds with TIR of approximately 70% [[25](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR25 "Beck RW, Bergenstal RM, Cheng P et al (2019) The relationships between time in range, hyperglycemia metrics, and HbA1c. J Diabetes Sci Technol 13(4):614–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932296818822496

")\]; however, it has also been reported that a wide range of TIR exists for a given HbA1c level \[[28](#ref-CR28 "Urakami T, Yoshida K, Kuwabara R et al (2020) Individualization of recommendations from the international consensus on continuous glucose monitoring-derived metrics in Japanese children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Endocr J 67(10):1055–1062.

https://doi.org/10.1507/endocrj.EJ20-0193

"),[29](#ref-CR29 "Kurozumi A, Okada Y, Mita T et al (2022) Associations between continuous glucose monitoring-derived metrics and HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 186:109836.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109836

"),[30](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR30 "Yoo JH, Kim JH (2020) Time in range from continuous glucose monitoring: a novel metric for glycemic control. Diabetes Metab J 44(6):828–839.

https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2020.0257

")\]. Additionally, this study was not powered for comparison of HbA1c between groups, and HbA1c was measured at each study centre instead of a central laboratory.The short time spent in AP mode (79.8%) might also have influenced the results. The short time spent in AP mode probably occurred because many participants turned it off to silence the hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia alarms due to alarm fatigue. Therefore, the system should be upgraded to address that problem. A smartphone app-based AID system, rather than a pump with an embedded algorithm, would also likely have contributed to the short time spent in AP mode. Smartphone app-based AID systems have demonstrated benefits in glucose control; thus, many of these systems have received approval from the Food and Drug Administration or a Conformite Europeene mark [[31](#ref-CR31 "Lee TTM, Collett C, Bergford S et al (2023) Automated insulin delivery in women with pregnancy complicated by type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 389(17):1566–1578. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2303911

"),[32](#ref-CR32 "Lum JW, Bailey RJ, Barnes-Lomen V et al (2021) A real-world prospective study of the safety and effectiveness of the loop open source automated insulin delivery system. Diabetes Technol Ther 23(5):367–375.

https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2020.0535

"),[33](/article/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y#ref-CR33 "Messer LH, D’Souza E, Merchant G et al (2023) Smartphone bolus feature increases number of insulin boluses in people with low bolus frequency. J Diabetes Sci Technol 18(1):10–13.

https://doi.org/10.1177/19322968231191796

")\]. However, this system requires the user to always have their smartphone nearby.A limitation of our study is that it was conducted only in South Korea, which could limit the generalisability of the results. Moreover, the study cohort had excellent mean glucose control at baseline; thus, they may not be representative of the broader population of people with type 1 diabetes. Further studies are also needed in other age groups and among people who are pregnant. Additionally, we did not perform analyses based on sex. Finally, we did not adjust the level of significance for multiplicity in secondary analyses, and thus all secondary analyses in this study should be regarded as exploratory.

In conclusion, this multicentre RCT demonstrated that a tubeless, on-body AID system is safe and offers better glycaemic control than a tubeless, on-body SAP in adults with type 1 diabetes.

Abbreviations

AID:

Automated insulin delivery

AP:

Artificial pancreas

CGM:

Continuous glucose monitoring

DTSQ:

Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire

DTSQc:

DTSQ change version

ITSQ:

Insulin Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire

MDI:

Multiple daily insulin injections

SAP:

Sensor-augmented pump

TAR:

Time above range

TBR:

Time below range

TIR:

Time in range

References

- Steele C, Hagopian WA, Gitelman S et al (2004) Insulin secretion in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 53(2):426–433. https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.53.2.426

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Cryer PE (2010) Hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 39(3):641–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2010.05.003

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Maia FFR, Araújo LR (2007) Efficacy of continuous glucose monitoring system (CGMS) to detect postprandial hyperglycemia and unrecognized hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 75(1):30–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2006.05.009

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM et al (2019) State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016–2018. Diabetes Technol Ther 21(2):66–72. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2018.0384

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Sherr JL, Heinemann L, Fleming GA et al (2023) Automated insulin delivery: benefits, challenges, and recommendations. A Consensus Report of the Joint Diabetes Technology Working Group of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetologia 66(1):3–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-022-05744-z

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Moser O, Riddell MC, Eckstein ML et al (2020) Glucose management for exercise using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and intermittently scanned CGM (isCGM) systems in type 1 diabetes: position statement of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and of the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) endorsed by JDRF and supported by the American Diabetes Association (ADA). Diabetologia 63(12):2501–2520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05263-9

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Holt RIG, DeVries JH, Hess-Fischl A et al (2021) The management of type 1 diabetes in adults. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia 64(12):2609–2652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05568-3

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR et al (2023) 7. Diabetes technology: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 46(Suppl 1):S111–S127. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-S007

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hur KY, Moon MK, Park JS et al (2021) 2021 Clinical practice guidelines for diabetes mellitus of the Korean Diabetes Association. Diabetes Metab J 45(4):461–481. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2021.0156

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Park J, Park N, Han S et al (2022) A 4-week, two-center, open-label, single-arm study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of EOPatch in well-controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab J 46(6):941–947. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2021.0299

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Brown SA, Forlenza GP, Bode BW et al (2021) Multicenter trial of a tubeless, on-body automated insulin delivery system with customizable glycemic targets in pediatric and adult participants with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 44(7):1630–1640. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-0172

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Baek JH, Lee WJ, Lee BW et al (2021) Age at diagnosis and the risk of diabetic nephropathy in young patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab J 45(1):46–54. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2019.0134

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Bradley C, Gamsu DS (1994) Guidelines for encouraging psychological well-being: report of a Working Group of the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe and International Diabetes Federation European Region St Vincent Declaration Action Programme for Diabetes. Diabet Med 11(5):510–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.1994.tb00316.x

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Anderson RT, Skovlund SE, Marrero D et al (2004) Development and validation of the insulin treatment satisfaction questionnaire. Clin Ther 26(4):565–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90059-8

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Bradley C (1999) Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire. Change version for use alongside status version provides appropriate solution where ceiling effects occur. Diabetes Care 22(3):530–532. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.22.3.530

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Brown SA, Kovatchev BP, Raghinaru D et al (2019) Six-month randomized, multicenter trial of closed-loop control in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 381(18):1707–1717. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1907863

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Boughton CK, Hovorka R (2021) New closed-loop insulin systems. Diabetologia 64(5):1007–1015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05391-w

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Moon SJ, Jung I, Park CY (2021) Current advances of artificial pancreas systems: a comprehensive review of the clinical evidence. Diabetes Metab J 45(6):813–839. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2021.0177

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhang JY, Shang T, Chattaraj S et al (2021) Advances in insulin pump infusion sets symposium report. J Diabetes Sci Technol 15(3):705–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932296821999080

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Deiss D, Adolfsson P, Alkemade-van Zomeren M et al (2016) Insulin infusion set use: European perspectives and recommendations. Diabetes Technol Ther 18(9):517–524. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2016.07281.sf

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Pickup JC, Yemane N, Brackenridge A, Pender S (2014) Nonmetabolic complications of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion: a patient survey. Diabetes Technol Ther 16(3):145–149. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2013.0192

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lebenthal Y, Lazar L, Benzaquen H, Shalitin S, Phillip M (2012) Patient perceptions of using the OmniPod system compared with conventional insulin pumps in young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 14(5):411–417. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2011.0228

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR et al (2023) 6. Glycemic targets: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 46(Suppl 1):S97–S110. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-S006

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Yu J, Lee SH, Kim MK (2022) Recent updates to clinical practice guidelines for diabetes mellitus. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 37(1):26–37. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2022.105

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Beck RW, Bergenstal RM, Cheng P et al (2019) The relationships between time in range, hyperglycemia metrics, and HbA1c. J Diabetes Sci Technol 13(4):614–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932296818822496

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wadwa RP, Reed ZW, Buckingham BA et al (2023) Trial of hybrid closed-loop control in young children with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 388(11):991–1001. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2210834

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Breton MD, Kanapka LG, Beck RW et al (2020) A randomized trial of closed-loop control in children with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 383(9):836–845. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2004736

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Urakami T, Yoshida K, Kuwabara R et al (2020) Individualization of recommendations from the international consensus on continuous glucose monitoring-derived metrics in Japanese children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Endocr J 67(10):1055–1062. https://doi.org/10.1507/endocrj.EJ20-0193

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kurozumi A, Okada Y, Mita T et al (2022) Associations between continuous glucose monitoring-derived metrics and HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 186:109836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109836

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yoo JH, Kim JH (2020) Time in range from continuous glucose monitoring: a novel metric for glycemic control. Diabetes Metab J 44(6):828–839. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2020.0257

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lee TTM, Collett C, Bergford S et al (2023) Automated insulin delivery in women with pregnancy complicated by type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 389(17):1566–1578. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2303911

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lum JW, Bailey RJ, Barnes-Lomen V et al (2021) A real-world prospective study of the safety and effectiveness of the loop open source automated insulin delivery system. Diabetes Technol Ther 23(5):367–375. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2020.0535

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Messer LH, D’Souza E, Merchant G et al (2023) Smartphone bolus feature increases number of insulin boluses in people with low bolus frequency. J Diabetes Sci Technol 18(1):10–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/19322968231191796

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Ji Yoon Kim, Sang-Man Jin & Jae Hyeon Kim - Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Eun Seok Kang - Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Soo Heon Kwak - Division of Endocrinology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Yeoree Yang - Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Republic of Korea

Jee Hee Yoo - Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Jae Hyun Bae - Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, Daegu, Republic of Korea

Jun Sung Moon - Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Chang Hee Jung - Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, Samsung Changwon Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Changwon, Republic of Korea

Ji Cheol Bae & Sunghwan Suh - Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Sun Joon Moon - Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Republic of Korea

Sun Ok Song - Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, College of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Suk Chon

Authors

- Ji Yoon Kim

- Sang-Man Jin

- Eun Seok Kang

- Soo Heon Kwak

- Yeoree Yang

- Jee Hee Yoo

- Jae Hyun Bae

- Jun Sung Moon

- Chang Hee Jung

- Ji Cheol Bae

- Sunghwan Suh

- Sun Joon Moon

- Sun Ok Song

- Suk Chon

- Jae Hyeon Kim

Corresponding author

Correspondence toJae Hyeon Kim.

Ethics declarations

Acknowledgements

Some of the data were presented as an abstract at the 59th Annual Meeting of the EASD in 2023.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Korea Medical Device Development Fund funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT; the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy; the Ministry of Health and Welfare; and the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (grant number: RS-2020-KD000056). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author’s relationships and activities

The authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

Contribution statement

S-MJ and JHK contributed to the conception and design of the study. JYK, S-MJ, ESK, SHK, YY, JHY, JHB, JSM, CHJ, JCB, SS, SJM, SOS, SC and JHK conducted data collection. JYK, S-MJ and JHK interpreted the results. JYK wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, with revisions by JYK, S-MJ and JHK. JYK, S-MJ, ESK, SHK, YY, JHY, JHB, JSM, CHJ, JCB, SS, SJM, SOS, SC and JHK contributed to reviewing the work critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published. JHK is the guarantor of this work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ji Yoon Kim and Sang-Man Jin contributed equally to this study as first authors.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J.Y., Jin, SM., Kang, E.S. et al. Comparison between a tubeless, on-body automated insulin delivery system and a tubeless, on-body sensor-augmented pump in type 1 diabetes: a multicentre randomised controlled trial.Diabetologia 67, 1235–1244 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y

- Received: 31 December 2023

- Accepted: 05 March 2024

- Published: 18 April 2024

- Version of record: 18 April 2024

- Issue date: July 2024

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-024-06155-y

Keywords

Profiles

- Jae Hyun Bae View author profile

- Jun Sung Moon View author profile

- Chang Hee Jung View author profile

- Sun Ok Song View author profile

- Suk Chon View author profile

- Jae Hyeon Kim View author profile