ESUR prostate MR guidelines 2012 (original) (raw)

Abstract

The aim was to develop clinical guidelines for multi-parametric MRI of the prostate by a group of prostate MRI experts from the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR), based on literature evidence and consensus expert opinion. True evidence-based guidelines could not be formulated, but a compromise, reflected by “minimal” and “optimal” requirements has been made. The scope of these ESUR guidelines is to promulgate high quality MRI in acquisition and evaluation with the correct indications for prostate cancer across the whole of Europe and eventually outside Europe. The guidelines for the optimal technique and three protocols for “detection”, “staging” and “node and bone” are presented. The use of endorectal coil vs. pelvic phased array coil and 1.5 vs. 3 T is discussed. Clinical indications and a PI-RADS classification for structured reporting are presented.

Key Points

• This report provides guidelines for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in prostate cancer.

• Clinical indications, and minimal and optimal imaging acquisition protocols are provided.

• A structured reporting system (PI-RADS) is described.

Introduction

In their lifetime, 1 in 6 men will be clinically diagnosed with prostate cancer. This accounts for annually 350,000 cases, which is 25% of all new male malignancies diagnosed in Europe [1–4]. Currently, digital rectal examination (DRE), serum prostate specific antigen (PSA)—a non-specific blood test—and trans-rectal ultrasound (TRUS) guided biopsy—where the target is mostly invisible—are used as diagnostic tools. Advances in MRI show promise for improved detection and characterisation of prostate cancer, using a multi-parametric approach, which combines anatomical and functional data. Thus far optimal acquisition and evaluation have not been agreed [5], and as is often the case in clinical practice, it is not satisfactory to await conclusions from large scale imaging and oncological trials. As a first step, the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) has called upon Europe-wide expertise to produce a set of guidelines on MRI on prostate cancer.

Methods

An ESUR working group of prostate MRI experts had informal discussions at international congresses and by e-mail. This crystallised into a series of specialist sub-groups. The criteria for group inclusion were radiologists with at least 3 years of experience in prostate MRI (>50/year), conducting research comparing image results with pathological specimens, co-working with urologists, and producing peer reviewed international articles. Over a 21/2-year period five meetings took place. Based on the recommendations of the sub-group chairs a consensus document was established and finalised by two consensus meetings and e-mail discussion.

Section 1: clinical use of MRI

Multi-parametric MRI

Recommended use of MRI in prostate cancer consists of multi-parametric (mp-MRI). This includes a combination of high-resolution T2-weighted images (T2WI), and at least two functional MRI techniques, as these provide better characterisation than T2WI with only one functional technique [6–9]. Within an mp-MRI examination, the relative clinical value of its component techniques differs. In addition to T2WI MRI, which mainly assesses anatomy, diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) [10–15] and MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) [16, 17] add specificity to lesion characterisation, while dynamic contrast enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) has a high sensitivity in cancer detection [9, 18, 19].

Clinical use of MRI

If PSA is elevated (>3–4 ng/mL) or DRE indicates suspected tumour, TRUS-guided biopsy will be performed to detect potential cancer, and assess its extent, volume and aggression. But, PSA has low specificity (36%), thus increased PSA is not equivalent with tumour. Also, normal PSA does not exclude tumour. Finally, TRUS biopsy underestimates the extent and grade of prostate cancer.

Based on PSA findings, DRE results and histopathological findings at TRUS biopsy, treatment is determined. Localised prostate cancer can be stratified into three groups based on the likelihood of tumour spread and recurrence:

- Low-risk: PSA <10 ng/mL, and biopsy Gleason score ≤6, and clinical stage T1–T2a

- Intermediate-risk: PSA 10–20 ng/mL, or biopsy Gleason score 7, or clinical stage T2b or T2c

- High-risk: PSA >20 ng/mL, or Gleason score 8–10, or clinical stage >T2c.

Treatment options: role of MRI

Decisions about imaging patients with newly diagnosed prostate cancer are determined by “intention to treat” (see Table 1).

Table 1 Treatment options: role of MRI

Low-risk patients

Treatment intention is radical surgery, radiotherapy or active surveillance (AS). Mp-MRI can be helpful in managing low risk patients and guide them towards AS, by confirming the absence of significant intra-prostatic disease. Additionally, mp-MRI can be used to help nerve and continence sparing surgery, and to focus radiotherapy.

Intermediate-risk patients

Being staged for curative intent. In this group the chance of extra-prostatic spread rises significantly. Thus it is advisable to perform mp-MRI in this group for detecting minimal extra-capsular disease by means of a “staging protocol” (Table 2B).

Table 2 Acquisition protocols: minimum requirements

High-risk patients

In high risk patients, bone scintigraphy or MRI to detect skeletal or nodal metastases is recommended. Here the “node and bone protocol” is advised (see Table 2C). If information is required about the local stage, the “staging protocol” may additionally be performed.

Lymph node staging of prostate cancer using conventional MRI is unreliable, as 70% of metastatic lymph nodes in prostate cancer are often small (<8 mm). If however, the a priori risk of having nodal metastases is >40%, MRI or CT should be performed [20]. Urologists use a lower a priori threshold of 10–17% to perform pelvic lymph node dissection [20].

MRI to determine tumour aggression

Mp-MRI techniques give increased conspicuity of tumour detection within the prostate and highlight areas of more aggressive disease within a short examination time (“detection protocol”, Table 2A). The prediction of the Gleason score is better assessed by DWI and 1H-MRSI compared with T2WI and DCE-MRI [21].

In low-risk patients considered for AS, monitoring involves [22–27]:

- PSA testing—every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6 months

- Regular DRE

- Repeat prostate TRUS-guided biopsies every 2–3 years.

Mp-MRI before AS is advocated, as it allows detection of adverse prognostic features such as tumour volume, and higher grade tumours, particularly in the anterior and apical lesions. DCE-MRI and DWI plus T2WI are highly accurate in detecting tumours >0.5 cc volume [18, 28]. Furthermore, MRSI plus T2WI have been reported to be very helpful in both excluding and detecting high-grade cancers >0.5 cc (sensitivity 93%, NPV 98%) [29, 30]. The results of mp-MRI can be used to direct further biopsy for more accurate grading of the tumour.

Mp-MRI in men suspected to have prostate cancer with negative previous TRUS biopsy

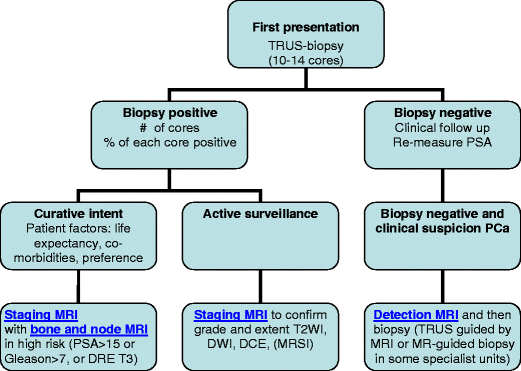

When TRUS biopsy is negative, and an interval rise in PSA justifies further investigation, mp-MRI using the “detection protocol” (Table 2A) must be applied before further TRUS-guided biopsy. MR-guided biopsy based on mp-MRI has shown superior results [21, 31–34]. Figure 1 summarises the role of MRI in undiagnosed and primary diagnosed prostate cancer.

Fig. 1

Algorithm in imaging men referred with elevated serum prostate specific antigen (PSA), abnormal digital rectal examination (DRE), or family history of prostate cancer

Investigating men post-therapy with PSA rise

Mp-MRI can be considered to be a tool to evaluate the prostatic fossa in patients with low PSA recurrence (values ranged between 0.2–2 ng/mL) where according to the EAU, other techniques (PET, TRUS biopsy) are not recommended [[35](/article/10.1007/s00330-011-2377-y#ref-CR35 "Panebianco V, Sciarra A, Lisi D et al (2011) Prostate cancer: 1HMRS-DCEMR at 3T versus [(18)F]choline PET/CT in the detection of local prostate cancer recurrence in men with biochemical progression after radical retropubic prostatectomy (RRP). Eur J Radiol. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.095

")\]. When curative aggressive treatment (e.g. salvage radiotherapy) is considered, in addition to T2WI, DCE-MRI and DWI should always be performed using the “detection protocol” \[[36](/article/10.1007/s00330-011-2377-y#ref-CR36 "Pasquier D, Hugentobler A, Masson P (2009) Which imaging methods should be used before salvage radiotherapy after prostatectomy for prostate cancer? Cancer Radiother 13:173–181")–[39](/article/10.1007/s00330-011-2377-y#ref-CR39 "Yakar D, Hambrock T, Huisman H, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa CA, van Lin E (2010) Feasibility of 3T dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance-guided biopsy in localizing local recurrence of prostate cancer after external beam radiation therapy. Invest Radiol 45:121–125")\]. Nodes and bone can be evaluated with the “node and bone” protocol.Section 2: MRI sequences for prostate gland evaluation

T2-weighted MR imaging

T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) provides the best depiction of the prostate’s zonal anatomy and capsule. T2WI is used for prostate cancer detection, localisation and staging. T2WI alone is not recommended because additional functional techniques improve both sensitivity and specificity. T2WI are obtained in 2–3 planes. The axial T2WI sequence must cover the entire prostate and seminal vesicles, and are orthogonal to the rectum. The phase encoding direction is left-to-right so that motion artefact does not overlap the prostate. Bowel motion artefacts should be reduced by administering an anti-peristaltic agent. The patient should be instructed about the importance of not moving during image acquisition. An endorectal coil (ERC) is not an absolute requirement at either 1.5 T or 3 T, but a pelvic phased array (PPA) coil with a minimum of 16 channels is required.

Prostate cancer typically manifests as a round or ill-defined, low-signal-intensity focus in the peripheral zone (PZ; Fig. 2a). However, various conditions such as prostate intra-epithelial neoplasia, prostatitis, haemorrhage, atrophy, scars and post-treatment changes can mimic cancer on T2WI. Tumours located in the transition zone (TZ) are more challenging to detect, as the signal intensity characteristics of the TZ and cancer usually overlap [40]. TZ tumour is often shown as a homogeneous signal mass with indistinct margins (“erased charcoal sign”, Fig. 3a, f). A lenticular (Fig. 3a) or “water-drop” shape is typical. These tumours often invade the pseudo-capsule with extension into the transition zone, or anterior fibro-muscular zone [40]. High-grade cancers tend to have a lower SI than low-grade cancers [41].

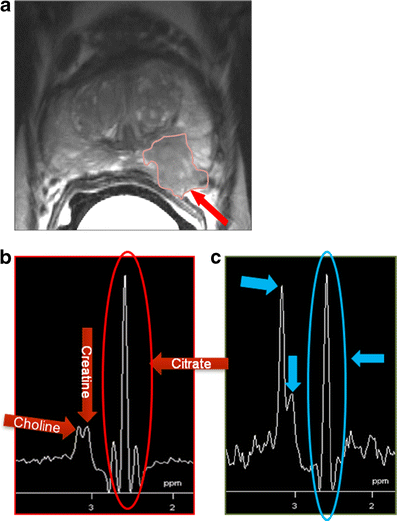

Fig. 2

A 65-year-old man with stage T3a Gleason 4+3 prostate cancer at the left peripheral zone (PZ). a On the axial T2WI at mid-prostate level in the left PZ there is a low signal lesion (outlined) with obliteration of the recto-prostatic angle and extra-capsular extension (arrow). b Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) of the normal right side shows low choline+creatine, whereas on (c) MRSI of the tumour shows high choline+creatine. The choline peak of tumour is as equally as high as the citrate peak. This results in a PI-RADS score for MRSI of 3

Fig. 3

A 75-year-old man. After five negative trans-rectal ultrasound (TRUS) biopsies PSA rose to 32 ng/mL, PCa3 = 62. Multi-parametric (Mp)-MRI was performed. a On axial T2WI there is a lenticular area with homogeneous low signal intensity (SI) and unsharp borders: “erased charcoal sign” (outlined), in the mid-prostate level in ventral transition zone (TZ) which is located anterior to the “organised chaos” of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). This pathological area originates from anterior fibromuscular stroma, and thus has a PI-RADS T2WI score of 5. b On the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map this region has a minimum ADC value of 650 (dark area); c On the b = 1400 image this area is white. This results in a PI-RADS score for diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) of 5. d This region shows a curve type 3 (wash-out), and on (e) T2WI with ktrans overlay, there is asymmetric, rather focal enhancement. This gives a PI-RADS score for dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MRI of 3 + 2 = 5. f shows the anterior location of the tumour on sagittal T2WI. As MRSI was not performed the sum PI-RADS score is 15/15, which argues in favour of an aggressive (significant) tumour. Thus the overall PI-RADS score for probability of being a significant cancer is 5. MR-guided biopsy revealed a Gleason 4 + 5 = 9 tumour. As the images clearly indicate a tumour, one may argue that one of the parameters may be obviated. However, mp-MRI is not only meant to “detect” a tumour, but also to predict its aggression. If all parameters point into the same direction, the chance of a clinically “significant” tumour (that is Gleason 4+3 or higher) is extremely high. If there is discordance it may be prostatitis or an insignificant (Gleason 3+3) cancer

The interpretation of T2WI includes evaluation of the capsule, seminal vesicles and posterior bladder wall for extra-prostatic tumour invasion. Criteria for extra-capsular extension are abutment; irregularity and neurovascular bundle thickening; bulge, loss of capsule and capsular enhancement; measurable extra-capsular disease; obliteration of the recto-prostatic angle. For seminal vesicle infiltration the criteria are: expansion; low T2 signal intensity; filling in of the prostate–seminal vesicle angle; enhancement and impeded diffusion (see Table 4).

Caveats and conclusions

T2WI alone is sensitive but not specific for prostate cancer and should be improved using two functional techniques.

Lesion detection is particularly problematic in the TZ because benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) looks like cancer [42]. However, presence of an “erased charcoal sign” in a lenticular lesion is highly suggestive of cancer.

Biopsy-related haemorrhage can cause artefacts that mimic cancer and limit lesion localisation and staging. To prevent this, the time interval between the biopsy procedure and MRI should be at least 4–6 weeks [41] and preliminary T1WI can be done to exclude biopsy-related haemorrhage. If significant haemorrhage is seen, the patient can be rescheduled 3–4 weeks later to allow resolution of the haemorrhage.

Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI

Dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MRI following the administration of gadolinium-based contrast medium is the most common imaging method for evaluating tumour vascularity [43]. As normal prostate is also highly vascular, a comparison of pre- and post-gadolinium images is usually insufficient to discern prostate cancer [44, 45]. A fast and direct method of characterising prostatic vascular pharmacokinetic features is high temporal resolution DCE-MRI (<10 s). DCE-MRI consists of a series of axial T1WI gradient echo sequences covering the entire prostate during and after IV bolus injection (2–4 mL/s) of gadolinium-based contrast medium [46, 47]. T1WI DCE-MRI imaging data can be assessed in three ways: qualitatively, semi-quantitatively or quantitatively.

DCE-MRI for prostate cancer detection, localisation, staging and recurrence detection

Hara et al have shown that DCE-MRI is able to detect clinically important prostate cancer in 93% of cases [48]. In patients with previous negative TRUS-guided biopsy sessions and rising PSA level, DCE-MRI plays an important role in lesion detection (Fig. 3d, e) [49].

Several studies have found that DCE-MRI is superior to T2WI for prostate cancer localisation.

Although the literature is sparse, available data suggest that DCE may improve staging. Thus, DCE-MRI is essential for the detection of post-prostatectomy [36, 37] and -radiotherapy recurrences [38, 39].

Caveats and conclusions

Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI is a valuable tool for MRI of prostate cancer, improving tumour localisation and local staging. However, it should always be combined with T2WI and DWI, as discrimination among prostatitis, BPH and prostate cancer in the TZ is more challenging with DCE-MRI alone.

Diffusion weighted MRI

Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) is a powerful clinical tool, as it allows apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps to be calculated, enabling qualitative and quantitative assessment of prostate cancer aggressiveness. Cancer shows a lower ADC value than normal prostate tissue. Furthermore ADC values correlate with Gleason scores [10–15].

Diffusion weighted imaging should be acquired in the axial plane with an echo planar imaging sequence employing parallel imaging. Motion probing gradients should be applied in three orthogonal directions and adapted to the quality of the SNR. The minimal requirements are b-values of 0, 100, and 800–1000 s/mm2. The choice of these values enables calculation of diffusion sensitive ADC values (by excluding the b = 0 data from the ADC calculation). For optimal DWI, the b-values are: 0, 100, 500, and 800–1000 s/mm2. TE should be as short as achievable (typically <90 ms).

Apparent diffusion coefficient maps can be generated from the index DWI data on the MR console itself, and have to be analysed qualitatively and quantitatively.

Prostate cancer demonstrates high signal intensity on DWI at high b-values and low signal intensity/value on ADC maps [50–52]. For qualitative assessment high b-value (800–1000) DW images and ADC maps should be used. These should be evaluated in combination with T2WI for the anatomical detail. However, some normal prostatic tissue, especially in the TZ, may reveal high signal intensity on DWI and low ADC, thus mimicking tumour. This may be overcome by using very high b-values (>1000 s/mm2).

For quantitative assessment ADC values are used. However, there is variability when using different field strengths, different b-values, and different models to fit the data. Also, there is a considerable inter-patient variability. Thus absolute values should be used with care. Until now DWI has not given additional information for staging.

Caveats and conclusions

Diffusion weighted imaging is an essential component of mp-MRI (Fig. 3a–c). It provides information about tumour aggressiveness, and improves specificity in prostate cancer detection compared with T2WI alone. DWI correlates well with tumour volume of the index prostatic lesions. It should, therefore, be part of routine assessments of patients with prostate cancer.

Diffusion weighted imaging is, however, affected by magnetic susceptibility effects resulting in spatial distortion and signal loss. Large b-values are required to suppress normal prostate tissue background signal and ADC maps should be used to minimise T2 shine-through [50].

MR spectroscopic imaging

Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) is able to show the lower levels of citrate and higher levels of choline of prostate cancer compared with benign tissue [53]. MRSI is performed with a 3D chemical shift imaging protocol (details can be found in Appendix 3). The use of an ERC is imperative at 1.5 T, but optional at 3 T. The volume of interest (VOI) is aligned to axial T2WIs to maximise coverage of the whole prostate, while minimising contamination by surrounding tissue. It is partitioned into a matrix of at least 8 × 8 × 8 phase-encoding steps. Applying spectral selective water and lipid suppression close to the prostatic margins reduces unwanted water and lipid signals in the VOI.

After post-processing, using commercially available software packages, spectral information is overlaid on T2WIs.The relevant metabolites are citrate (marker of benign tissue), creatine (insignificant for diagnosis, but difficult to resolve from choline), and choline (marker of malignant tissue). In quantitative analysis, the peak integrals of all metabolites are estimated by means of the choline-plus-creatine-to-citrate (CC/C) ratio. Cancer in PZ and TZ should have in at least two adjacent voxels a CC/C ratio exceeding respectively 2 and 3 standard deviations above the mean ratio [53–57]. In qualitative analysis, the peak heights of citrate and choline are visually compared (Fig. 2b, c) [58].

Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging can be used to predict the presence or absence of cancer [21, 29, 30]. It also provides information about lesion aggressiveness, but does not give staging information owing to its poor spatial resolution. Thus, MRSI is a valid tool for detecting cancer recurrence [59–65] and monitoring therapy response [66].

Caveats and conclusions

Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging provides valuable information about lesion aggression, but requires expertise, use of an endorectal coil at 1.5 T, and adds time to the examination. Whether MRSI is included in the mp-MRI examination depends on personal local experience and availability.

Section 3. MR equipment

MR coils

The ERC+PPA coil combination provides excellent SNR and remains state-of-the-art for staging prostate cancer. However, it has recognised drawbacks in terms of cost and patient acceptability.

Many articles have shown good results in tumour detection/localisation without the ERC when the mp-MRI approach is used. Further work is, however, necessary to:

- a.

Compare tumour detection/localisation, and staging accuracy of PPA vs. ERC+PPA coil MRI. - b.

Assess the clinical relevance of minimal extra-prostatic disease detected by ERC usage.

Imaging at 3 T

Prostate imaging at 3 T benefits from higher SNR, and enables high quality imaging within a short time without the use of an ERC. Data on 3 T for prostate cancer MRI are still conflicting [67]. Thus further research on this topic is needed

Limitations of 3 T MRI are shorter T2 and longer T1 relaxation times [68], problems with susceptibility artefacts [69, 70], dielectric effect, specific absorption rate [71], and the homogeneity of the magnetic field. However, hardware, multi-channel coil, and parallel imaging technique improvements are currently solving most of these problems.

Section 4. Integration, reporting and communication of multi-parametric prostate MRI data

Mp-MRI data need to be presented to clinical colleagues in a simple but meaningful way, preferably using a structured reporting scheme, which consists of the following items:

- PI-RADS score which relays the probability of cancer risk and its aggression, plotted on a scheme

- Location and, probability of extra-prostatic disease

- Pertinent incidental findings.

Scoring system for mp-MRI (PI-RADS)

A scoring system similar to that employed successfully by breast radiologists (BI-RADS for X-ray mammography, breast ultrasound and MRI) should be used and prospectively validated for prostate mp-MRI. Scoring should include:

- As a minimum requirement division of the prostate 16 regions, as an optimal requirement into 27 regions.

- Individual lesions being given a (PI-RADS) score.

- Maximum dimension of the largest abnormal lesion.

Reviews of the literature show that Likert-like five-grade scoring systems are often used to evaluate mp-MRI of the prostate [28, 72–76]. In keeping with this, a recent consensus meeting of prostate cancer experts used the UCLA-RAND appropriateness method and recommended that a five-point scale be used for the PI-RADS scoring:

- Score 1 = Clinically significant disease is highly unlikely to be present

- Score 2 = Clinically significant cancer is unlikely to be present

- Score 3 = Clinically significant cancer is equivocal

- Score 4 = Clinically significant cancer is likely to be present

- Score 5 = Clinically significant cancer is highly likely to be present.

The criteria for assigning scores to lesions identified by each technique are not yet generally accepted. The most developed is the quantitative evaluation of 1H-MRSI [57, 76]. Based on consensus opinion and literature evidence the ESUR experts propose to use the PI-RADS classification, which is presented in Table 3. In this scoring system every parameter: T2WI (PZ and TZ different description), DWI, DCE-MRI and MRSI is scored on a five-point scale. Additionally, each lesion is given an overall score, to predict its chance of being a clinically significant cancer.

Table 3 PI-RADS scoring system

In addition to Table 3, for quantitative analysis of 1.5 T MRSI, the following score can be used:

At least two adjacent voxels with CC/C ratios, which have:

- >4 standard deviations from the mean normal value: 5 points

- >3–4 standard deviations from the mean normal value: 4 points

- >2–3 standard deviations from the mean normal value: 3 points

- >1–2 standard deviations from the mean normal value: 2 points

- ≤1 standard deviation from the mean normal value: 1 point

In addition to the PI-RADS score for the probability of a lesion to be significant, extra-prostatic involvement should also be scored on a five-point scale (Table 4). This should include: extra-capsular extension, seminal vesicle infiltration, distal sphincter, rectal wall, neurovascular bundles and bladder neck. Here, also, all aspects should have a scoring range of 1 to 5.

Table 4 Scoring of extra-prostatic disease

Conclusion and considerations

These recommendations argue cogently that mp-MRI should be an integral part of prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment. Although disputed by some urologists [68], the minimal requirements for the acquisition of MR images can be met with the generally available 1.5- and 3-T MR systems.

References

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ (2009) Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin 59:225–249

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Carter HB, Piantadosi S, Isaacs JT (1990) Clinical evidence for and implications of the multistep development of prostate cancer. J Urol 143:742–746

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Parkin DM, Bray FI, Devesa SS (2001) Cancer burden in the year 2000. The global picture. Eur J Cancer 37(Suppl 8):S4–S66

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Konety BR, Bird VY, Deorah S, Dahmoush L (2005) Comparison of the incidence of latent prostate cancer detected at autopsy before and after the prostate specific antigen era. J Urol 174:1785–1788, discussion 1788

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Dickinson L, Ahmed HU, Allen C, Barentsz JO, Carey B et al (2011) Magnetic resonance imaging for the detection, localisation, and characterisation of prostate cancer: recommendations from a European consensus meeting. Eur Urol 59:477–494

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Franiel T, Stephan C, Erbersdobler A, Dietz E, Maxeiner A et al (2011) Areas suspicious for prostate cancer: MR-guided biopsy in patients with at least one transrectal US-guided biopsy with a negative finding—multiparametric MR imaging for detection and biopsy planning. Radiology 259:162–172

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kitajima K, Kaji Y, Fukabori Y, Yoshida K, Suganuma N et al (2010) Prostate cancer detection with 3T MRI: comparison of diffusion-weighted imaging and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in combination with T2-weighted imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 31:625–631

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Fütterer JJ, Heijmink SW, Scheenen TW, Veltman J, Huisman HJ et al (2006) Prostate cancer localization with dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging and proton MR spectroscopic imaging. Radiology 241:449–458

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Tanimoto A, Nakashima J, Kohno H, Shinmoto H, Kuribayashi S (2007) Prostate cancer screening: the clinical value of diffusion-weighted imaging and dynamic MR imaging in combination with T2-weighted imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 25:146–152

Article PubMed Google Scholar - van As NJ, de Souza NM, Riches SF, Morgan VA, Sohaib SA et al (2009) A study of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in men with untreated localised prostate. Eur Urol 56:981–987

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Zelhof B, Pickles M, Liney G, Gibbs P, Rodrigues G et al (2009) Correlation of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance data with cellularity in prostate cancer. BJU Int 103:883–888

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Tamada T, Sone T, Jo Y, Toshimitsu S, Yamashita T et al (2008) Apparent diffusion coefficient values in peripheral and transition zones of the prostate: comparison between normal and malignant prostatic tissues and correlation with histologic grade. J Magn Reson Imaging 28:720–726

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Turkbey B, Shah VP, Pang Y, Bernardo M, Xu S et al (2011) Is apparent diffusion coefficient associated with clinical risk scores for prostate cancers that are visible on 3-T MR images? Radiology 258:488–495

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Itou Y, Nakanishi K, Narumi Y, Nishizawa Y, Tsukuma H (2011) Clinical utility of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values in patients with prostate cancer: can ADC values contribute to assess the aggressiveness of prostate cancer? J Magn Reson Imaging 33:167–172

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hambrock T, Huisman HJ, van Oort IM, Witjes JA, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa CA et al (2011) Relationship between apparent diffusion coefficients at 3.0-T MR imaging and Gleason grade in peripheral zone prostate cancer. Radiology 259:453–461

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Villeirs GM, Oosterlinck W, Vanherreweghe E, De Meerleer GO (2010) A qualitative approach to combined magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Eur J Radiol 73:352–356

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Scheenen TW, Klomp DW, Roll SA, Futterer JJ, Barentsz JO et al (2004) Fast acquisition-weighted three-dimensional proton MR spectroscopic imaging of the human prostate. Magn Reson Med 52:80–88

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Girouin N, Mège-Lechevallier F, Tonina Senes A, Bissery A et al (2007) Prostate dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI with simple visual diagnostic criteria: is it reasonable? Eur Radiol 17:1498–1509

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Yoshizako T, Wada A, Hayashi T, Uchida K, Sumura M et al (2008) Usefulness of diffusion-weighted imaging and dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of prostate transition-zone cancer. Acta Radiol 49:1207–1213

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Hovels AM, Heesakkers RA, Adang EM et al (2008) The diagnostic accuracy of CT and MRI in the staging of pelvic lymph nodes in patients with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Clin Radiol 63:387–395

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron D, Carroll P, Coakley F (2008) Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in prostate cancer: present and future. Curr Opin Urol 18:71–77

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Klotz L (2005) Active surveillance for prostate cancer: for whom? J Clin Oncol 23:8165–8169

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Klotz L (2005) Active surveillance with selective delayed intervention using PSA doubling time for good risk prostate cancer. Eur Urol 47:16–21

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Klotz L (2008) Active surveillance for prostate cancer: trials and tribulations. World J Urol 26:437–442

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Klotz L (2008) Active surveillance for favorable risk prostate cancer: what are the results, and how safe is it? Semin Radiat Oncol 18:2–6

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Klotz LH (2005) Active surveillance for good risk prostate cancer: rationale, method, and results. Can J Urol 12(Suppl 2):21–24

PubMed Google Scholar - Soloway MS, Soloway CT, Williams S, Ayyathurai R, Kava B, Manoharan M (2008) Active surveillance; a reasonable management alternative for patients with prostate cancer: the Miami experience. BJU Int 101:165–169

PubMed Google Scholar - Villers A, Puech P, Mouton D, Leroy X, Ballereau C et al (2006) Dynamic contrast enhanced, pelvic phased array magnetic resonance imaging of localized prostate cancer for predicting tumor volume: correlation with radical prostatectomy findings. J Urol 176:2432–2437

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Villeirs GM, De Meerleer GO, De Visschere PJ, Fonteyne VH, Verbaeys AC, Oosterlinck W (2011) Combined magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy in the assessment of high grade prostate carcinoma in patients with elevated PSA: a single-institution experience of 356 patients. Eur J Radiol 77:340–345

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kumar R, Nayyar R, Kumar V et al (2008) Potential of magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging in predicting absence of prostate cancer in men with serum prostate-specific antigen between 4 and 10 ng/mL: a follow-up study. Urology 72:859–863

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hambrock T, Somford DM, Hoeks C et al (2010) Magnetic resonance imaging guided prostate biopsy in men with repeat negative biopsies and increased prostate specific antigen. J Urol 183:520–527

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Amsellem-Ouazana D, Younes P, Conquy S et al (2005) Negative prostatic biopsies in patients with a high risk of prostate cancer. Is the combination of endorectal MRI and magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging (MRSI) a useful tool? A preliminary study. Eur Urol 47:582–586

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Prando A, Kurhanewicz J, Borges AP, Oliveira EM Jr, Figueiredo E (2005) Prostatic biopsy directed with endorectal MR spectroscopic imaging findings in patients with elevated prostate specific antigen levels and prior negative biopsy findings: early experience. Radiology 236:903–910

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hambrock T, Hoeks C, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa C, Scheenen T, Fütterer J (2012) Prospective assessment of prostate cancer aggressiveness using 3-T diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging-guided biopsies versus a systematic 10-core transrectal ultrasound prostate biopsy cohort. Eur Urol 61:177–184

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Panebianco V, Sciarra A, Lisi D et al (2011) Prostate cancer: 1HMRS-DCEMR at 3T versus [(18)F]choline PET/CT in the detection of local prostate cancer recurrence in men with biochemical progression after radical retropubic prostatectomy (RRP). Eur J Radiol. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.095

- Pasquier D, Hugentobler A, Masson P (2009) Which imaging methods should be used before salvage radiotherapy after prostatectomy for prostate cancer? Cancer Radiother 13:173–181

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Cirillo S, Petracchini M, Scotti L et al (2009) Endorectal magnetic resonance imaging at 1.5 Tesla to assess local recurrence following radical prostatectomy using T2-weighted and contrast-enhanced imaging. Eur Radiol 19:761–769

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Haider MA, Chung P, Sweet J, Toi A, Jhaveri K et al (2008) Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for localization of recurrent prostate cancer after external beam radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 70:425–430

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Yakar D, Hambrock T, Huisman H, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa CA, van Lin E (2010) Feasibility of 3T dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance-guided biopsy in localizing local recurrence of prostate cancer after external beam radiation therapy. Invest Radiol 45:121–125

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Akin O, Sala E, Moskowitz CS et al (2006) Transition zone prostate cancers: features, detection, localization, and staging at endorectal MR imaging. Radiology 239:784–792

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Wang L, Mazaheri Y, Zhang J, Ishill NM, Kuroiwa K, Hricak H (2008) Assessment of biologic aggressiveness of prostate cancer: correlation of MR signal intensity with Gleason grade after radical prostatectomy. Radiology 246:168–176

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Oto A, Kayhan A, Jiang Y et al (2010) Prostate cancer: differentiation of central gland cancer from benign prostatic hyperplasia by using diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 257:715–723

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Collins DJ, Padhani AR (2004) Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of tumor perfusion. Approaches and biomedical challenges. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag 23:65–83

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Huisman HJ, Engelbrecht MR, Barentsz JO (2001) Accurate estimation of pharmacokinetic contrast-enhanced dynamic MRI parameters of the prostate. J Magn Reson Imaging 13:607–614

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Alonzi R, Padhani AR, Allen C (2007) Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI in prostate cancer. Eur J Radiol 63:335–350

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Barentsz JO, Engelbrecht M, Jager GJ et al (1999) Fast dynamic gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging of urinary bladder and prostate cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging 10:295–304

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Engelbrecht MR, Huisman HJ, Laheij RJ et al (2003) Discrimination of prostate cancer from normal peripheral zone and central gland tissue by using dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 229:248–254

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hara N, Okuizumi M, Koike H, Kawaguchi M, Bilim V (2005) Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) is a useful modality for the precise detection and staging of early prostate cancer. Prostate 62:140–147

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Beyersdorff D, Taupitz M, Winkelmann B et al (2002) Patients with a history of elevated prostate-specific antigen levels and negative transrectal US-guided quadrant or sextant biopsy results: value of MR imaging. Radiology 224:701–706

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Haider MA, van der Kwast TH, Tanguay J et al (2007) Combined T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted MRI for localization of prostate cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 189:323–328

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kim CK, Park BK, Lee HM, Kwon GY (2007) Value of diffusion-weighted imaging for the prediction of prostate cancer location at 3T using a phased-array coil: preliminary results. Invest Radiol 42:842–847

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Lim HK, Kim JK, Kim KA, Cho KS (2009) Prostate cancer: apparent diffusion coefficient map with T2-weighted images for detection—a multireader study. Radiology 250:145–151

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Testa C, Schiavina R, Lodi R et al (2007) Prostate cancer: sextant localization with MR imaging, MR spectroscopy, and 11 C-choline PET/CT. Radiology 244:797–806

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Jung JA, Coakley FV, Vigneron DB et al (2004) Prostate depiction at endorectal MR spectroscopic imaging: investigation of a standardized evaluation system. Radiology 233:701–708

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB, Hricak H, Narayan P, Carroll P, Nelson SJ (1996) Three-dimensional H-1 MR spectroscopic imaging of the in situ human prostate with high (0.24–0.7-cm3) spatial resolution. Radiology 198:795–805

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Sciarra A, Panebianco V, Ciccariello M et al (2010) Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (1H-MRSI) and dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (DCE-MRI): pattern changes from inflammation to prostate cancer. Cancer Invest 28:424–432

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Futterer JJ, Scheenen TW, Heijmink SW et al (2007) Standardized threshold approach using three-dimensional proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging in prostate cancer localization of the entire prostate. Invest Radiol 42:116–122

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Yuen JS, Thng CH, Tan PH et al (2004) Endorectal magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy for the detection of tumor foci in men with prior negative transrectal ultrasound prostate biopsy. J Urol 171:1482–1486

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Sciarra A, Panebianco V, Salciccia S et al (2008) Role of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and proton MR spectroscopic imaging in the detection of local recurrence after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Eur Urol 54:589–600

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Zakian KL, Hricak H, Ishill N et al (2010) An exploratory study of endorectal magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy of the prostate as preoperative predictive biomarkers of biochemical relapse after radical prostatectomy. J Urol 184:2320–2327

Article PubMed Google Scholar - De Visschere PJ, De Meerleer GO, Futterer JJ, Villeirs GM (2010) Role of MRI in follow-up after focal therapy for prostate carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 194:1427–1433

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Rouviere O, Vitry T, Lyonnet D (2010) Imaging of prostate cancer local recurrences: why and how? Eur Radiol 20:1254–1266

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Shukla-Dave A, Hricak H, Ishill N et al (2009) Prediction of prostate cancer recurrence using magnetic resonance imaging and molecular profiles. Clin Cancer Res 15:3842–3849

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Pucar D, Shukla-Dave A, Hricak H et al (2005) Prostate cancer: correlation of MR imaging and MR spectroscopy with pathologic findings after radiation therapy-initial experience. Radiology 236:545–553

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Coakley FV, Teh HS, Qayyum A et al (2004) Endorectal MR imaging and MR spectroscopic imaging for locally recurrent prostate cancer after external beam radiation therapy: preliminary experience. Radiology 233:441–448

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Pickett B, Kurhanewicz J, Coakley F, Shinohara K, Fein B, Roach M III (2004) Use of MRI and spectroscopy in evaluation of external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 60:1047–1055

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kim CK, Park BK, Kim B (2010) Diffusion-weighted MRI at 3T for the evaluation of prostate cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 194:1461–1469

Article PubMed Google Scholar - BottomLey PA, Foster TH, Argersinger RE, Pfeifer LM (1984) A review of normal tissue hydrogen NMR relaxation times and relaxation mechanisms from 1-100 MHz: dependence on tissue type, NMR frequency, temperature, species, excision, and age. Med Phys 11:425–448

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Ahmed HU, Kirkham A, Arya M et al (2009) Is it time to consider a role for MRI before prostate biopsy? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 6:197–206

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Cornfeld DM, Weinreb JC (2007) MR imaging of the prostate: 1.5 T versus 3 T. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 15:433–448, viii

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Leautaud A, Marcus C, Ben SD, Bouche O, Graesslin O, Hoeffel C (2009) Pelvic MRI at 3.0 Tesla. J Radiol 90(3 Pt 1):277–286

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Mueller-Lisse U, Scheidler J, Klein G, Reiser M (2005) Reproducibility of image interpretation in MRI of the prostate: application of the sextant framework by two different radiologists. Eur Radiol 15:1826–1833

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Nogueira L, Wang L, Fine SW et al (2010) Focal treatment or observation of prostate cancer: pretreatment accuracy of transrectal ultrasound biopsy and T2-weighted MRI. Urology 75:472–477

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Arumainayagam N, Kumaar S, Ahmed HU et al (2010) Accuracy of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in detecting recurrent prostate cancer after radiotherapy. BJU Int 106:991–997

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Jung JA, Coakley FV, Vigneron DB et al (2004) Prostate depiction at endorectal MR spectroscopic imaging: investigation of a standardized evaluation system. Radiology 233:701–708

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Villers A, Lemaitre L, Haffner J, Puech P (2009) Current status of MRI for the diagnosis, staging and prognosis of prostate cancer: implications for focal therapy and active surveillance. Curr Opin Urol 19:274–282

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the following members of the ESUR Committee on the Prostate MRI Guidelines: Claire Allen, Michel Claudon, Francois Cornud, Ferdinand Frauscher, Nicolas Grenier, Alex Kirkham, Frederic Lefevre, Gareth Lewis, Ulrich Muller-Lisse, Anwar Padhani, Valeria Panebianco, Pietro Pavlica, Phillipe Puech, Jarle Rorvik, Andrea Rockall, Catherine Roy, Tom Scheenen, Harriet Thoeny, Baris Turkbey, Ahmet Turgut, Derya Yakar.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Radiology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Jelle O. Barentsz & Jurgen J. Fütterer - Brighton & Sussex University Hospital Trust, Eastern Road, Brighton, UK

Jonathan Richenberg - Department of Clinical Radiology, Royal Gwent Hospital, Newport, South Wales, UK

Richard Clements - Molecular Imaging Program, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA

Peter Choyke - University Of Cincinnati Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

Sadhna Verma - Division of Genitourinary Radiology, Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium

Geert Villeirs - Hospices Civils de Lyon, Department of Urinary and Vascular Imaging, Hôpital Edouard Herriot, Lyon, France

Olivier Rouviere - Université de Lyon, Lyon, France

Olivier Rouviere - Faculté de Médecine Lyon Est, Université Lyon 1, Lyon, France

Olivier Rouviere - Copenhagen University, Hospital Herlev, Herlev, Denmark

Vibeke Logager

Authors

- Jelle O. Barentsz

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jonathan Richenberg

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Richard Clements

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Peter Choyke

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sadhna Verma

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Geert Villeirs

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Olivier Rouviere

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Vibeke Logager

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jurgen J. Fütterer

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence toJelle O. Barentsz.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Barentsz, J.O., Richenberg, J., Clements, R. et al. ESUR prostate MR guidelines 2012.Eur Radiol 22, 746–757 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-011-2377-y

- Received: 16 October 2011

- Revised: 23 November 2011

- Accepted: 02 December 2011

- Published: 10 February 2012

- Issue Date: April 2012

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-011-2377-y