Evolutionary origin and phylogenetic analysis of the novel oocyte-specific eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E in Tetrapoda (original) (raw)

Introduction

The early development of metazoans relies heavily on the maternal stores accumulated in the egg during its growth. Amassing of nutrients during oogenesis secures an embryo’s independence from external energy sources and ensures rapid development during this vulnerable stage of an organism’s life. Another vital role played by the egg is imparting the initial programs for gene expression upon the nascent embryonic genome. This role is particularly pronounced in viviparous mammals, whose oocytes have minute amounts of yolk and embryos receive nutrition directly from mothers upon implantation. During the ooplasm-driven remodeling of parental genomes, transcription is barely, if at all, detectable. Thus, the initial embryonic genome is shaped by precise posttranscriptional and posttranslational mechanisms, which concomitantly create the dynamic molecular environment as early development proceeds. Upon completion of this genome remodeling, reinitiation of transcription demarcates “embryonic genome activation.” Henceforth, the embryonic genome gradually assumes control of development from “maternal command.”

The molecules that drive embryogenesis at these earliest stages are still poorly understood. However, it is well-known that posttranslational mechanisms, which govern initial embryonic development, rely on massive accumulation of transcripts during oogenesis. Indeed, during oocyte growth, many transcribed mRNAs are stored in the ooplasm as a “dormant” form for translation at later stages and are deadenylated. Translational recruitment of these stored mRNAs is typically manifested by lengthening of their limited 3′ poly(A) tails (Bachvarova 1992; Richter and Sonenberg 2005). Spatio-temporal regulation of translational activation of maternal mRNAs deposited during oocyte growth is a key mechanism providing new proteins during the final stages of oogenesis (i.e., maturation), and first stages of embryogenesis in virtually all metazoans. One model for mRNA translational regulation, based upon extensive studies from diverse model organisms, proposes how transcripts may be translated in the time- and stage-dependent fashion (Richter and Sonenberg 2005; Standart and Minshall 2008). In this model, a regulatory protein can be bound to a cognate motif in the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of mRNA. Concurrently, this RNA-binding protein may also be bound, either directly or via intermediate protein(s), to the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), an mRNA 5′-cap-binding protein. In the “closed” conformation, these protein–RNA interactions suppress translation by preventing formation of the preinitiation complex. Certain signaling events, such as phosphorylation of a 3′-UTR-bound regulatory protein, result in a conformational change to the complex, leading to recruitment of poly(A) polymerases to the 3′ end of mRNA, formation of the translational initiation complex on the 5′ end, and eventually leading to translation.

The eIF4E family of proteins consists of three large subfamilies, eIF4E1, eIF4E2, and eIF4E3. Genomic sequencing and analysis of various model organisms, as well as the analysis of EST databases, suggest the existence of multiple eIF4E-encoding genes within each of these subfamilies in most organisms (Joshi et al. 2005). The reason for this redundancy is not clear. While it is assumed that most eIF4E proteins possess at least some 5′-cap binding activity, to date, the most extensively studied and characterized is the eIF4E1 subfamily. Until recently, only one mammalian eIF4E1 member, encoded by the Eif4e gene, has been identified. Our analysis of the fully-grown mouse oocyte cDNA library revealed another gene, Eif4eloo (Eif4e1b in current nomenclature), which, indeed, is a second bona fide member of this subfamily in mammals (Evsikov et al. 2006). Unlike its ubiquitously expressed paralog Eif4e, transcription of Eif4e1b gene appears restricted to growing oocytes. To date, the Eif4e1b gene has been identified in genome assemblies of various mammals (Evsikov et al. 2006), while transcripts encoding eIF4E1B proteins from different species, including Homo sapiens, have been identified in the large-scale survey of GenBank mRNAs and ESTs aimed to categorize all available information on various eIF4E family proteins across all eukaryotes (Joshi et al. 2005).

In order to understand the role of Eif4e1b/Eif4eloo in the oocytes, we sought to delineate the phylogenetic history of this gene. Indeed, a similar eIF4E1 homolog, with the expression pattern restricted to oocytes, testis, and muscle, has been reported in the zebrafish, Danio rerio (Robalino et al. 2004). Interestingly, unlike “conventional” eIF4E, this D. rerio eIF4E-1B protein cannot substitute for endogenous eIF4E in complementation assays using _eif4e_-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae; furthermore, it lacks the 5′-cap-binding activity (Robalino et al. 2004). Recently, a similar eIF4E1B protein with similar biochemical properties has been also identified in the frog, Xenopus laevis (Minshall et al. 2007). Here, we used available genome sequences and whole-genome assemblies of model organisms to scrutinize the evolutionary relationships among members of the eIF4E1 subfamily in vertebrates and to identify the nonmammalian orthologs of Eif4e1b. To investigate the functional role of Eif4e1b as a regulator of translation during oocyte maturation, antisense morpholino oligonucleotides designed to suppress Eif4e1b mRNA translation were injected in immature, fully-grown Xenopus tropicalis oocytes.

Results and discussion

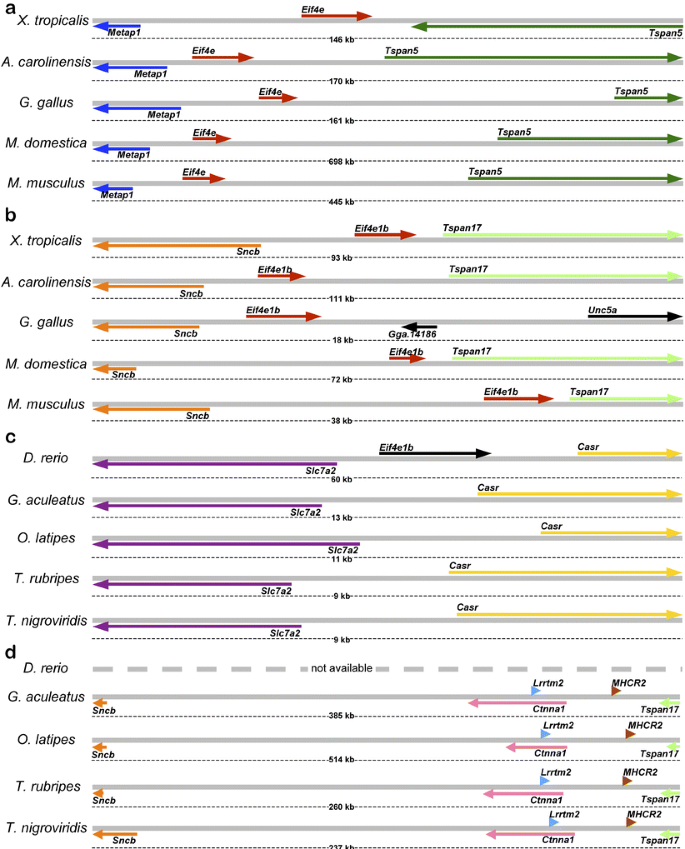

To determine the potential orthologs of Eif4e1b/Eif4eloo, we have identified, using TBLASTN program, the ESTs of three vertebrates, Anolis carolinensis, Gallus gallus, and Xenopus tropicalis, which share identity with Mus musculus eIF4E1B protein. The matching ESTs were next assembled into contigs, and the identities of resulting consensus cDNAs were established by aligning them, using BLAT, to the ENSEMBL genome assemblies of A. carolinensis, G. gallus, and X. tropicalis, respectively. As expected, some consensi aligned to the genomic regions of A. carolinensis, G. gallus, and X. tropicalis syntenic to the mammalian Eif4e gene, and the orthology was evidenced by colinearity of genes (Metap1_–_Eif4e_–_Tspan5) in the genomes of all examined species (Fig. 1a). Another group of EST consensi aligned to the genomic regions of A. carolinensis and X. tropicalis that were clearly syntenic to the M. musculus locus (Fig. 1b: Sncb_–_Eif4e1b_–_Tspan17). Similarly, one G. gallus cDNA aligned to the syntenic locus downstream of Sncb gene (Fig. 1b: Sncb_–_Eif4e1b_–_Unc5a). Interestingly, Tspan17 locus is apparently absent in this species as Unc5a, located immediately downstream of Eif4e1b in G. gallus (Fig. 1b), is located downstream of Tspan17 in other species (not shown). Virtual Northern blotting (i.e., analysis of the EST sources for the consensi that comprised Eif4e1b cDNAs in G. gallus, X. tropicalis, and A. carolinensis) identified that all X. tropicalis ESTs were from either oocyte, blastula, or gastrula cDNA libraries, while G. gallus and A. carolinensis ESTs were from ovarian cDNA libraries. Due to the limited amounts of ESTs available for a marsupial, Monodelphis domestica, Eif4e and Eif4e1b loci in these species were identified using TBLASTN search of genome assembly using M. musculus eIF4E1B. This search revealed two candidate genes; further examination of adjacent loci authenticated these candidates as bona fide orthologs of Eif4e and Eif4e1b, respectively (Fig. 1a,b). In summary, we have identified the orthologs of the previously described mammalian Eif4e1b gene (Evsikov et al. 2006) in the genomes of representatives for all major classes of Tetrapoda. In all examined species, the origin of the Eif4e1b gene is likely monophyletic, and its expression is commonly upregulated in oocytes and ovaries, suggesting conserved function(s) in female germline.

Fig. 1

Conservation of genomic structure for Eif4e and Eif4e1b loci in Tetrapoda. Colinearity of genes underscores the common phylogenetic origins for Eif4e (a) and Eif4e1b (b) in tetrapods. c The Danio rerio eif4e1b locus is not conserved among Actinopterygii genomes. d While the colinearity of Sncb and Tspan17 orthologs persists across vertebrates, fish genomes lack the Eif4e1b locus. Orthologs shown in the same color; nonorthologous genes shown in black

To further understand the evolutionary history of the Eif4e1b locus, we have performed the TBLASTN search of all D. rerio ESTs and cDNA sequences to detect the eIF4E-coding mRNAs in this species. Seven distinct eIF4E genes were identified, including previously reported eif4e1a and eif4e1b (Robalino et al. 2004; Suppl. Table 1). Multiple sequence alignment of corresponding proteins with eIF4E proteins of Tetrapoda using CLUSTALW confirmed that four D. rerio genes, eif4e1a, eif4e1b, zgc:101581 (Eif4e1_2), and zgc:110154 (Eif4e1_3) encode proteins of the eIF4E1 subfamily (Suppl. Fig. 1). To our surprise, while the zebrafish eIF4E1B is very similar to other eIF4E1B proteins and has a similarly restricted pattern of expression (Robalino et al. 2004), the D. rerio eif4e1b gene is not orthologous to either Eif4e1b or Eif4e loci of Tetrapoda. Indeed, alignment of eif4e1b cDNAs to the D. rerio genome identified the eif4e1b locus unambiguously (Fig. 1c). However, although the colinearity of flanking Slc7a2 and Casr genes is well-conserved, the genomes of other Actinopterygii species (Gasterosteus aculeatus, Oryzias latipes, Takifugu rubripes, and Tetraodon nigroviridis) lack any sign of eIF4E-encoding locus in the respective regions (Fig. 1c). Conversely, while the physical linkages of Sncb and Tspan17 loci persist among these four fish species and Tetrapoda, there is no _Eif4e_-like gene residing in this region of any Actinopterygii genome as well (Fig. 1d vs b). Together, these data indicate the lack of orthology between the D. rerio eif4e1b and the Eif4e1b of Tetrapoda.

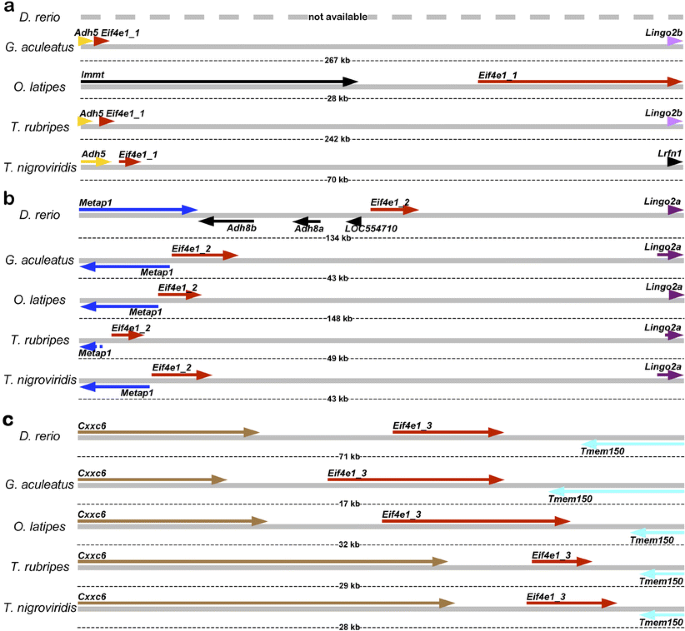

Further TBLASTN search of fish genome assemblies using D. rerio eIF4E1A, eIF4E1B, eIF4E1_2 and eIF4E1_3 protein sequences revealed three ostensibly orthologous groups of eIF4E1-encoding genes in Actinopterygii (Fig. 2; Suppl. Table 1). The physical linkage of Eif4e1_2 and Metap1 loci in all five species indicated Eif4e1_2 genes as “genuine” orthologs of Tetrapoda Eif4e genes (Fig. 2b vs 1a), while Eif4e1_1 (Fig. 2a) and Eif4e1_3 (Fig. 2c) loci are unique to Actinopterygii species. To test these conclusions, multiple sequence alignments of newly identified eIF4E1_1, eIF4E1_2, and eIF4E1_3 proteins of G. aculeatus, O. latipes, T. rubripes, and T. nigroviridis were performed to identify their relationships to the eIF4E1 family members of D. rerio and Tetrapoda (Suppl. Fig. 2). The results indicate that the eIF4E1_2 proteins of Actinopterygii are indeed the closest relatives of _Tetrapoda_’s eIF4E, while eIF4E1_1 and eIF4E1_3 are distinct clades of this subfamily. Furthermore, eif4e1a gene of D. rerio, absent in the (current) genome assembly, likely belongs to the Eif4e1_1 group, while no close relative for eif4e1b gene could be identified in any other currently available Actinopterygii genome. This may be due, in part, to the taxonomy of Actinopterygii, as D. rerio has a very distant relationship to any of the other surveyed species (Suppl. Table 2). Indeed, several likely eIF4E1B-encoding sequences were identified previously among cDNA and EST sequences of other fish species (Joshi et al. 2005). However, absence of the genome assemblies or even any considerable genomic sequence data precludes the studies of orthological relationships for these additional eif4e1b genes.

Fig. 2

Actinopterigyii genomes contain multiple members of eIF4E1 subfamily. Danio rerio expresses at least four members of this family (Suppl. Table 1), three of which have orthologs in other sequenced fish genomes. Genomic arrangement of loci for putative orthologs of zebrafish eif4e1a (Eif4e1_1) (a), zgc:101581 (Eif4e1_2) (b), and zgc:110154 (Eif4e1_3) (c) genes. Orthologs shown in the same color; nonorthologous genes shown in black

Overall, our data strongly indicate rapid diversification of eIF4E1 subfamily occurred during the time of whole-genome duplication in vertebrates (Nakatani et al. 2007). This diversity was lost during the early phylogenesis of Tetrapoda lineage and resulted in the fixation of merely two loci, the ubiquitous Eif4e and oocyte-restricted Eif4e1b, in these taxa. It is plausible that multiple _Eif4e1b_-like loci existed in the common ancestor of Actinopterygii and Tetrapoda; some of them were asymmetrically retained in Actinopterygii (e.g., eif4e1b locus in D. rerio), while others, such as the ancestral locus that spawned Eif4e1b of Tetrapoda, were subsequently lost in other lineages. Whatever the case, this provides an excellent example of convergent molecular evolution for eIF4E1B-encoding genes which, while being phylogenetically distinct in Actinopterygii vs Tetrapoda, endure selective pressure to encode functionally identical proteins, as well as to be preferentially expressed in female germline. In fact, this situation strongly resembles the “phylogenetic behavior” of some oocyte-expressed genes in mammals that we discovered previously. For example, some critical maternal effect genes sustain asymmetrical reduplications, and presumably strong selective pressure, to result in the formation of multiple homologous, but not orthologous, genes belonging to several distinct families (e.g., Nalp, Oasl, Oog, and others; Evsikov et al. 2006).

To address the function of eIF4E1B protein in the oocytes, morpholino antisense oligonucleotides (morpholinos) were injected to curb translation of its mRNA in the eggs of X. tropicalis. Unlike Xenopus laevis, whose allotetraploid genome allows each protein to be translated from two different mRNAs and thus renders translational suppression experiments unfeasible, X. tropicalis was the most suitable model to perform such studies because it has a diploid genome and retains much of the advantages found in X. laevis as a model embryological system (Carruthers and Stemple 2006). Although X. tropicalis stage VI oocytes express all eIF4E-encoding genes identified in the genome of this species (Fig. 3a), we were interested in the specific functions for the oocyte-specific isoform. Injection of anti-Eif4e1b morpholinos into freshly harvested X. tropicalis fully grown eggs per se did not result in any changes to oocyte morphology for up to 144 h of culture. This result implies that eIF4E1B protein is dispensable at this stage and may function later in oogenesis, such as meiotic maturation, or during early development. To test this hypothesis, oocytes injected with anti-Eif4e1b morpholino oligonucleotides were induced to complete meiosis with progesterone and the rates of meiotic maturation, measured by the appearance of “white spots” on animal poles, the gross morphological sign of metaphase spindle formation, were recorded. Since morpholinos only inhibit translation of cognate mRNA, progesterone treatment was applied to fully grown oocytes at 48 and 96 h postinjection to ensure sufficient time for intrinsic protein turnover of any preexisting eIF4E1B proteins. Two days after injection, anti-Eif4e1b morpholino treatment increased the number of matured oocytes at 3.5 h after progesterone treatment (\({\text{time}} \times {\text{treatment}}\,{\text{ $ \chi $ }}^2 = 49.6\), P < 0.0001), whereas no other time point was effected (Fig. 3b). Four days after treatment, two- to eightfold more oocytes receiving anti-Eif4e1b morpholino treatment (χ2 = 62.24, P < 0.0001) completed maturation 30–60 min faster compared to all three control groups (\({\text{time}} \times {\text{treatment}}\,{\text{ $ \chi $ }}^2 = 58.96\), P < 0.0001), respectively (Fig. 3c). A similar effect of meiotic acceleration by 30–60 min was obtained with oocytes induced with progesterone at 144 h postinjection (data not shown); however, in this case, maturation in all groups was delayed up to ∼7 h, most likely due to the adverse effects of prolonged culture.

Fig. 3

Gene expression of Eif4e1b and its function in oocytes of Xenopus tropicalis. a RT-PCR detection of eIF4E-encoding genes (Xt_Eif4e1b, Xt_Eif4e, Xt_Eif4e2a, Xt_Eif4e2b, Xt_Eif4e3), Xt-Gpcr13, Xt-Odc as positive controls of cDNA quality and H2O as a negative control. b, c Effects of blocking eIF4E1B translation on the resumption of meiosis and maturation in oocytes exposed to anti-Eif4e1b morpholino or control for 2 and 4 days

Interestingly, comparable acceleration of maturation was recently reported when the oocytes from another frog, X. laevis, were injected with an antibody that recognizes a likely ortholog of eIF4E1B in these species (Minshall et al. 2007). Overall, our data further underscore a novel, unexpected conclusion that the oocyte-specific eIF4E1B acts as a translational repressor of dormant maternal mRNAs. At first glance, this repressor activity is surprising, as all eIF4E1B and eIF4E proteins from Tetrapoda and D. rerio are identical at 98 out of 183 residues constituting the IF4E/CDC33 domain (Suppl. Fig. 3). Moreover, all the residues critical for 5′-cap mRNA binding and interactions with eIF4Gs or eIF4E-BPs are absolutely conserved among eIF4E1Bs and eIF4Es (Suppl. Fig. 3). Despite this striking sequence identity, our experimental data and the results from other laboratories suggest that, functionally, eIF4E1B is very different from “canonical” eIF4E. Indeed, assuming the functional identity among eIF4E1B proteins in vertebrates, the important characteristics of these proteins are weak mRNA cap and eIF4G-binding and strong affinity to 4E-T (Minshall et al. 2007; Robalino et al. 2004), an eIF4E transporter protein encoded by Eif4enif1 gene in mammals. Recently, a model based on the biochemical interactions of X. laevis eIF4E1B with 4E-T and CPEB in immature oocytes has been proposed (Standart and Minshall 2008). In this model, eIF4E1B, unlike “canonical” eIF4E, behaves as translational corepressor of CPE-containing maternal transcripts required for maturation, such as Cyclin B mRNA. Importantly, this proposed model may occur in mammalian systems as well because all three proteins are highly abundant in mouse oocytes (Evsikov et al. 2006; Villaescusa et al. 2006). In the future, studies of the biochemical interactions of eIF4E1B, which are beginning to be uncovered (Minshall et al. 2007; Robalino et al. 2004; Standart and Minshall 2008), will hopefully explain the exact mechanisms and roles in translational control of maternal mRNAs.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics

National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; Wheeler et al. 2008) BLAST engine was used for all GenBank searches. ESTs and cDNAs were downloaded from NCBI. EST sequences were assembled in consensus sequences as described (Evsikov et al. 2006), and the encoded protein sequences identified using ORF finder (NCBI). Searches against the genome assemblies for all species were performed using online search tools of ENSEMBL project (Flicek et al. 2008; http://www.ensembl.org/). The following genome assemblies were used: Anolis carolinensis, AnoCar1.0; Danio rerio, Zv7; Gallus gallus, WASHUC2; Gasterosteus aculeatus, BROAD S1; Monodelphis domestica, monDom5; Mus musculus, NCBI m37; Oryzias latipes, HdrR; Takifugu rubripes, FUGU 4.0; Tetraodon nigroviridis, TETRAODON 8.0; and Xenopus tropicalis, JGI 4.1. Multiple sequence alignments and their analyses were performed using MEGA 4.0 (Tamura et al. 2007). The protein sequences of eIF4E family members mentioned or identified in this study are provided in the Supplemental Table 3.

Antisense Oligonucleotides

To inhibit translation of Eif4e1b mRNA, the 25-mer morpholino antisense oligonucleotides, “morpholinos” (Gene Tools LLC, Philomath, OR, USA) were used. The sequence of anti-Eif4e1b morpholino (5′-CAGCTGCTGCCATTCTGCTATACAA-3′) was designed according to manufacturer’s recommendations using the 5′-end sequence of the X. tropicalis Eif4e1b mRNA containing the AUG start codon (EST AL890091 and the corresponding region of X. tropicalis genome assembly). This sequence does not match any mRNA but Xt_Eif4e1b, or any other region of the sequenced genome. The “standard control morpholino” (5′-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3′) is designed towards a splice-generating mutation at position 705 of β-globin pre-mRNA found in human thallasemia. This morpholino is commonly used as a control in egg microinjection experiments and does not have any known target or any significant biological activity in either X. laevis or X. tropicalis. Stock concentrations for both morpholinos were 1 mM in sterile water. For injection, 10 nl of 200 μM morpholino, or sterile water, was injected per oocyte.

Oocyte collection, microinjection, and maturation assays

Follicle-cell-free X. tropicalis stage VI oocytes were obtained by collagenase treatment (2% type I collagenase, 0.1% SBTI, 0.1% BSA in 1× Modified Ringer’s [MR] medium: 100 mM NaCl, 1.8 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 5 mM Na-HEPES; pH adjusted to 7.8 with NaOH) for 1 h at room temperature with gentle shaking (De Sousa and Masui 1990). Oocytes were washed 10 times in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (28 mM K2HPO4, 72 mM KH2PO4, pH 6.5) and five times in 1× MR, and sorted on a 100-mm agarose-coated Petri dish in 1× MR. Oocytes were placed in the OR3 medium (50% Leibovitz’s L-15 medium, 15 mM HEPES, 100 μg/ml gentamycin, 50 U/ml mystatin, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin) for 2–3 h at 25°C and processed for microinjection (Gallo et al. 1995). Batches of 25 oocytes were placed in 35-mm plastic Petri dishes with a piece of nylon mesh (0.8–1 mm openings) attached to the bottom. Before injection, level of OR3 medium was adjusted to 200–400 μm above oocytes, so they were held in place by the mesh on the bottom and surface tension on top. Injections were performed with a Picospritzer apparatus (Parker Hannifin, Cleveland, OH, USA) using needles pulled from glass borosilicate capillaries (outer diameters of needle tips were 17–19 μm). After injection of morpholino or water (or no injection, control), the oocytes were cultured for 48, 96, or 144 h in OR3 in agarose-coated Petri dishes at 25°C. Maturation was induced in oocytes by incubation in 1 μg/ml progesterone in OR3 for 6–10 h at 25°C. The meiotic progression was monitored by counting the number of oocytes with the clearly defined white spot on the animal pole every 30 min beginning at 3 h after the start of progesterone treatment. Fifty oocytes per experimental group (anti-Eif4e1b morpholino-injected, control morpholino-injected, water-injected and uninjected) in two independent experiments conducted on different days were used.

Gene expression

RNA was isolated from X. tropicalis fully-grown oocytes (a generous gift from Dr. Laurinda Jaffe, University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT, USA). RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase (Quiagen) and used for cDNA first strand synthesis (Superscript III, Invitrogen). Conditions for PCR were optimized using FailSafe PCR system (Roche). The PCR amplification program was: 97°C 1 min; 35 cycles of 95°C/30 s; 58°C/30 s; 72°C/45 s; 72°C 10 min; 4°C infinity. PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized by UV transillumination. Sequences of primers used for RT-PCR studies are listed in Suppl. Table 4.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics (mean and SEM) were reported as the percent of mature oocytes at each time interval. To detect statistical differences for the effects of treatment, time, and the interaction of time × treatment on the total number of matured oocytes, an ordinal logistic fit model was used to calculate the χ2 likelihood ratio tests, with differences considered significant at P < 0.05 (JMP 7 software, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).