Deciphering the global genetic structure of Spirometra mansoni and S. erinaceieuropaei based on 28S ribosomal RNA: Insights into taxonomical revaluation and population dynamics (original) (raw)

Abstract

The latest taxonomy recognizes two Spirometra species in Asia: S. mansoni and S. asiana, with the former exhibiting a global distribution. The isolates analyzed in this study were classified accordingly, and a S. mansoni isolate from India was identified using morphology, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), sequencing, and phylogenetics. Furthermore, a global analysis of genetic diversity, haplotype network structure, and population dynamics of Spirometra spp. was conducted using the 28S rRNA marker. Phylogenetic analysis of Spirometra sequences (n = 104) revealed two distinct clades: a larger clade with Asian (China, Korea, and India) and African (Egypt) sequences (reclassified as S. mansoni) and a smaller clade with European (Latvia and Finland) sequences (true S. erinaceieuropaei). The Asian S. mansoni population showed high haplotype diversity (Hd = 0.821 ± 0.035) and moderate nucleotide diversity (π = 0.00695 ± 0.00054). Asian haplotypes were closely related, with Hap_6 being the most common. The European S. erinaceieuropaei population formed a single haplotype (Hap_15) and exhibited no genetic variation. Population dynamics suggested expansion in global and Asian populations, with strong geographic structuring. The global mismatch distribution indicated a structured population with variable genetic diversity among populations. Genetic differentiation between continents was evident and AMOVA results confirmed that most genetic variation was due to differences among continental populations. This study confirmed S. mansoni in India, clarified its global spread, and provided insights into its population dynamics. The results can inform public health strategies, improve understanding of these zoonotic tapeworms, and help reduce transmission risks to humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spirometra tapeworms, belonging to the family Diphyllobothriidae, cause spirometrosis in canids and felids, their definitive hosts, where they inhabit the small intestine (Soulsby 1982; Yamasaki et al. 2021). The life cycle involves copepods as first intermediate hosts harbouring procercoids, while amphibians, reptiles, fishes, mammals, and birds act as second intermediate or paratenic hosts, harbouring plerocercoids/spargana (Mueller [1974](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR33 "Mueller JF (1974) The biology of Spirometra. J Parasitol 60:3–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/3278670

"); Yamasaki et al. [2017](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR46 "Yamasaki Y, Morishima H, Sugiyama H (2017) Cestode infections in Japan. IASR 38:74–76"); Kuchta et al. [2021](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR23 "Kuchta R, Kołodziej-Sobocińska M, Brabec J, Młocicki D, Sałamatin R, Scholz T (2021) Sparganosis (Spirometra) in Europe in the molecular era. Clin Infect Dis 72(5):882–890"); Liu et al. [2022](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR30 "Liu W, Gong T, Chen S, Liu Q, Zhou H et al (2022) Epidemiology, diagnosis, and prevention of sparganosis in Asia. Animals 12(12):1578.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12121578

")). Humans can accidentally serve as hosts for spargana larvae, leading to sparganosis, or, more rarely, for adult _Spirometra_ tapeworms, causing spirometrosis (Liu et al. [2015](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR29 "Liu Q, Li MW, Wang ZD, Zhao GH, Zhu XQ (2015) Human sparganosis: a neglected food borne zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis 15:1226–1235.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00133-4

"); Le et al. [2017](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR26 "Le AT, Do LQT, Nguyen HBT, Nguyen HNT, Do AN (2017) Case report: the first case of human infection by adult of Spirometra erinaceieuropaei in Vietnam. BMC Infect Dis 17:1–4")).Adult Spirometra mansoni infection in domestic dogs and cats is generally subclinical; however, affected animals particularly cats may develop diarrhoea, vomiting, emaciation, and enteritis (Adolph and Peregrine 2021; Bowman [2021](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR6 "Bowman DD (2021) Diagnostic parasitology. In: Georgis’ parasitology for veterinarians, 11th edn. WB Saunders, pp 349–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-54396-5.00016-7

")). In humans, the spargana larvae can migrate to various tissues, including the brain, eyes, and organs, causing cerebral, ocular, and visceral sparganosis (Yoshikawa et al. [2010](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR49 "Yoshikawa M, Ouji Y, Nishiofuku M, Ishizaka S, Nawa Y (2010) Sparganosis cases reported in Japan in the recent decade, 2000–2009. Clin Parasitol 21:33–36"); Liu et al. [2015](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR29 "Liu Q, Li MW, Wang ZD, Zhao GH, Zhu XQ (2015) Human sparganosis: a neglected food borne zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis 15:1226–1235.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00133-4

")). A global systematic review and meta-analysis found a higher prevalence of _Spirometra_ infection in intermediate hosts (frogs and snakes) than in definitive hosts (dogs and cats), indicating a greater risk of human sparganosis. Regional variations were noted, with snakes and frogs being more commonly infected in Asia, whereas dogs and cats had higher infection rates in Africa and Oceania, respectively (Badri et al. [2022](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR2 "Badri M, Olfatifar M, KarimiPourSaryazdi A, Zaki L, Madeira de Carvalho LM, Fasihi Harandi M, Barikbin F, Madani P, Vafae Eslahi A (2022) The global prevalence of Spirometra parasites in snakes, frogs, dogs, and cats: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vet Med Sci 8(6):2785–2805")).The taxonomy of Spirometra is complicated, with many reported species being debated due to morphological similarities, intraspecific variations, and limited distinguishing features (Kuchta and Scholz 2017; Scholz et al. 2019; Jeon and Eom 2019). The broad host range of adult worms and the morphological indistinguishability of larval stages further contribute to the uncertainty in species identification (Mueller [1974](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR33 "Mueller JF (1974) The biology of Spirometra. J Parasitol 60:3–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/3278670

"); Daly [1981](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR8 "Daly JJ (1981) Sparganosis. In: Beran GW (ed) Steele JH. Parasitic zoonoses, CRC Press, Boca Raton, CRC handbook series in zoonoses. Section C, pp 293–312"); Kuchta and Scholz [2017](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR22 "Kuchta R, Scholz T (2017) Diphyllobothriidea Kuchta, Scholz, Brabec & Bray, 2008. In: Caira JN, Jensen K (eds) Planetary biodiversity inventory (2008–2017): Tapeworms from Vertebrate Bowels of the Earth. University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, pp 167–189")). Nearly 50 nominal species have been documented (Scholz et al. [2019](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR41 "Scholz T, Kuchta R, Brabec J (2019) Broad tapeworms (Diphyllobothriidae), parasites of wildlife and humans: recent progress and future challenges. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl 9:359–369")), but most were proposed based on poorly fixed specimens, specimens obtained from decomposed carcasses (Hernández-Orts et al. [2015](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR13 "Hernández-Orts JS, Scholz T, Brabec J, Kuzmina T, Kuchta R (2015) High morphological plasticity and global geographical distribution of the Pacific broad tapeworm Adenocephalus pacificus (syn. Diphyllobothrium pacificum): molecular and morphological survey. Acta Trop 149:168–178")), or examination of limited proglottids (Faust et al. [1929](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR11 "Faust EC, Campbell HE, Kellogg CR (1929) Morphological and biological studies on the species of Diphyllobothrium in China. Am J Epidemiol 9(3):560–583"); Wardle et al. [1974](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR45 "Wardle RA, Mac Leod JA, Radinovsky S (1974) Advances in the zoology of tapeworms. University of Minnesota Press, pp 1950–1970")). The reference species, _S. erinaceieuropaei_, is also poorly described and is known primarily from descriptions of its plerocercoid larval stage, which makes species differentiation challenging (Scholz et al. [2019](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR41 "Scholz T, Kuchta R, Brabec J (2019) Broad tapeworms (Diphyllobothriidae), parasites of wildlife and humans: recent progress and future challenges. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl 9:359–369"); Kuchta et al. [2021](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR23 "Kuchta R, Kołodziej-Sobocińska M, Brabec J, Młocicki D, Sałamatin R, Scholz T (2021) Sparganosis (Spirometra) in Europe in the molecular era. Clin Infect Dis 72(5):882–890")). Precise identification is crucial for understanding epidemiology, transmission, and pathogenic potential.Initial taxonomic revisions recognized four valid species, viz_., S. erinaceieuropaei_, S. mansonoides, S. pretoriensis, and S. theileri (Kamo 1999). However, molecular studies targeting multiple nuclear and mitochondrial genes have revealed substantial genetic diversity in Spirometra spp. Various genes, such as cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (coxI; Scholz et al. 2019; Yamasaki et al. 2021; Kuchta et al. 2021), NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (nad1; Eom et al. 2019; Jeon et al. 2018), cytochrome b (cytb; Zhang et al. 2015a, 2015b, Zhang et al. 2016), large subunit of nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (28S rRNA; Tang et al. 2017; Bagrade et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2022) and small subunit of nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (18S rRNA; Bagrade et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2022), have been widely used to resolve phylogenetic relationships and uncover cryptic lineages. Recent integrative taxonomy combining morphology, epidemiology, and genetics has redefined the genus into seven distinct species or lineages based on coxI gene analysis (Kuchta et al. 2021, 2024; Yamasaki et al. 2024). These include S. erinaceieuropaei in Europe, S. decipiens in South America, S. folium in Africa, S. mansoni with a global distribution (Eurasia, Oceania, Africa, North and South America), S. theileri in Africa, Spirometra spp. 2 and Spirometra spp. 3 representing American and North American lineages, respectively, and S. asiana in Asia (Kuchta et al. 2021; Vettorazzi et al. [2023](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR44 "Vettorazzi R, Norbis W, Martorelli SR, García G, Rios N (2023) First report of Spirometra (Eucestoda; Diphyllobothriidae) naturally occurring in a fish host. Folia Parasitol 70:8. https://doi.org/10.14411/fp.2023.008

"); Yamasaki et al. [2024](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR48 "Yamasaki H, Sugiyama H, Morishima Y, Kobayashi H (2024) Description of Spirometra asiana sp. nov. (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidae) found in wild boars and hound dogs in Japan. Parasitol Int 98:102798")). Some species, such as _S. mansonoides_, _S. ranarum_, and _S. raillieti_, remain uncharacterized due to limited molecular data, highlighting the need for further research to clarify the taxonomy of this genus (Kuchta et al. [2024](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR24 "Kuchta R, Phillips AJ, Scholz T (2024) Diversity and biology of Spirometra tapeworms (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidea), zoonotic parasites of wildlife: a review. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl 24:100947")).Spirometra, a globally distributed parasite, predominantly causes human sparganosis in East Asia (China, Korea, Japan, Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia). However, in the Indian subcontinent, approximately 26 sporadic human cases have been reported, manifesting in various forms such as cutaneous, ocular, cerebral, and visceral (Nawa et al. 2024; Rathore et al. 2024). While Spirometra infections have been documented in domestic (Pal et al. 1981; Saleque et al. 1990) and wild animals (Patnaik and Acharjyo 1970; Kavitha et al. 2014) across India, species-level identification remains limited, with most cases relying on morphological identification. Molecular studies are scarce, and existing reports often lack clarity, with one instance of reclassification from S. erinaceieuropaei to S. mansoni (Yamasaki et al. 2024). Given this knowledge gap, this study aimed to identify a Spirometra isolate from a dog in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India, using the 28S rRNA and coxI genes for precise species identification. Given the recent taxonomic updates of Spirometra based on the coxI gene, which had not been updated in GenBank, we sought to determine the species identity of Meerut isolate. Furthermore, our approach integrated taxonomic re-evaluation, global genetic diversity, and population genetics analysis of Spirometra spp. using the partial 28S rRNA sequences. We also reclassified several previously unverified Spirometra sequences as S. mansoni based on their monophyletic grouping with authenticated S. mansoni sequences.

Materials and methods

Sample collection, genomic deoxy ribonucleic acid (DNA) extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing

A few segments of an adult tapeworm were recovered from a dog’s (Canis lupus familiaris) vomit at the Teaching Veterinary Clinical Complex, Meerut, Uttar Pradesh. After washing in normal saline, the segments were flattened between two slides, fixed in AFA (Alcohol, Formalin, and Acetic acid in 85:10:5), and stained with alcoholic borax carmine (Grenacher’s stain). The specimens were then destained in 1% acid alcohol, dehydrated in an ascending series of ethanol, cleared in xylene, and mounted on glass slides using DPX for microscopic examination. A portion of the sample, preserved in 10% formalin, was sent for molecular analysis. The DNA extraction was performed using the QIAamp DNA FFPE tissue kit (Qiagen, Germany), and attempts were made to amplify the mitochondrial coxI (446 bp) and nuclear 28S rRNA (298 bp) genes, as described by Lee et al. (2007). Although both genes were targeted, only 28S rRNA sequences were successfully obtained and sequenced in triplicate using Sanger’s method to ensure accuracy, as described previously (Moudgil and Nehra 2025). Unfortunately, high-quality coxI sequences were not obtained despite multiple attempts. The 28S rRNA sequences were analyzed, and a consensus sequence was generated and submitted to GenBank (Accession number PQ350405).

Phylogenetic and haplotype data analyses, genetic diversity and population dynamics

The sequence generated in this study was subjected to Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) analysis, and the Spirometra sequences with 99–100% query coverage and 99.8–100% identity were retrieved from GenBank (n = 104). These sequences were trimmed to ensure equal length, aligned using Multiple Alignment using Fast Fourier Transform (MAFFT) tool (Katoh et al. 2019), and subjected to phylogenetic analysis in MEGA 12.0.7 (Kumar et al. 2024). Cephalochlamys namaquensis (DQ925324) sequence served as an outgroup. The JC + I substitution model was selected (Jukes and Cantor 1969), and a maximum likelihood tree was constructed with 1000 bootstrap replications to assess tree reliability. This analysis involved 109 nucleotide sequences with 293 aligned positions. The details of the sequences used in this study are mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1 List of Spirometra spp. sequences (based on 28S ribosomal gene) used in the phylogenetic analysis and haplotype networking

The multiple sequence alignment file of Spirometra sequences (n = 104) was imported into DnaSP v6.12.03 to determine the number of haplotypes (Rozas et al. 2017). The haplotypes were grouped by country and continent, and various genetic diversity and neutrality indices were calculated for each population (Table 3). A median-joining network was constructed using PopART (Leigh and Bryant 2015) to visualize haplotype relationships (Bandelt et al. 1999). Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA), pairwise genetic differentiation (Fst), and gene flow (Nm) among continent-wise Spirometra populations were performed using Arlequin ver 3.5.2.2 (Excoffier and Lischer 2011). Additionally, a Mantel test was conducted in R Studio 4.3.2 (http://www.rstudio.com) to assess the degree of association between genetic differentiation (Fst) and geographic location.

Results

Morphological characterization

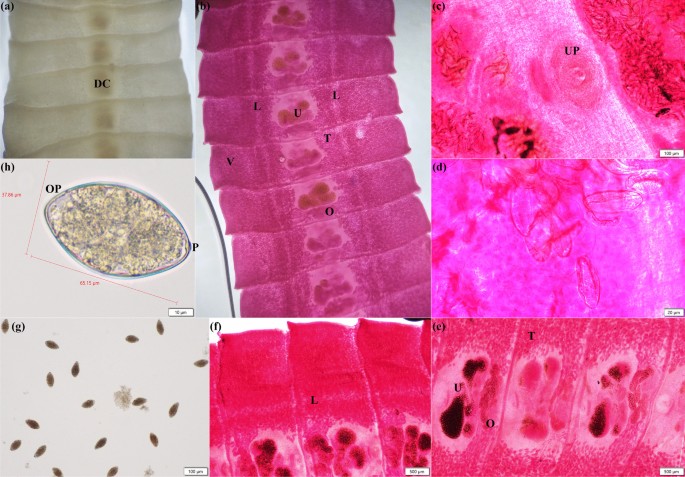

The morphology of Spirometra spp. was characterized by distinct features that were observed in its segments and eggs. Unstained mature segments exhibited dark central markings that were caused by the uterus and eggs (Fig. 1a). A stained mature segment revealed internal reproductive structures such as a spiral uterus containing eggs, an ovary, vitelline glands, and lateral excretory canals (Fig. 1b, d, e, f). The ventral view of the mature segment displayed a prominent uterine pore, which facilitated egg release (Fig. 1c). Eggs observed in vomitus were pointed at both ends, and a cone-shaped operculum and an abopercular protuberance were observed at opposite ends (Fig. 1g, h).

Fig. 1

Microscopic images of S. mansoni depicting various aspects of an adult worm’s morphology. a Unstained mature segments with dark central markings (DC) caused by uterus and eggs. b Boraxcarmine stained mature proglottids showing the spiral uterus (U), ovaries (O), vitelline glands (V), testes (T), and lateral excretory canals (L). c A ventral section of the mature segment highlighting the medial uterine pore (UP) and d eggs inside the uterus. e A magnified view of the mature segment’s spiral uterus packed (U) with eggs, ovaries (O), testes (T), and f lateral excretory canal (L). g, h Eggs in vomitus with pointed ends, and a cone-shaped operculum (OP) at one end and an abopercular protuberance (P) at the other

Phylogeny and haplotype networking

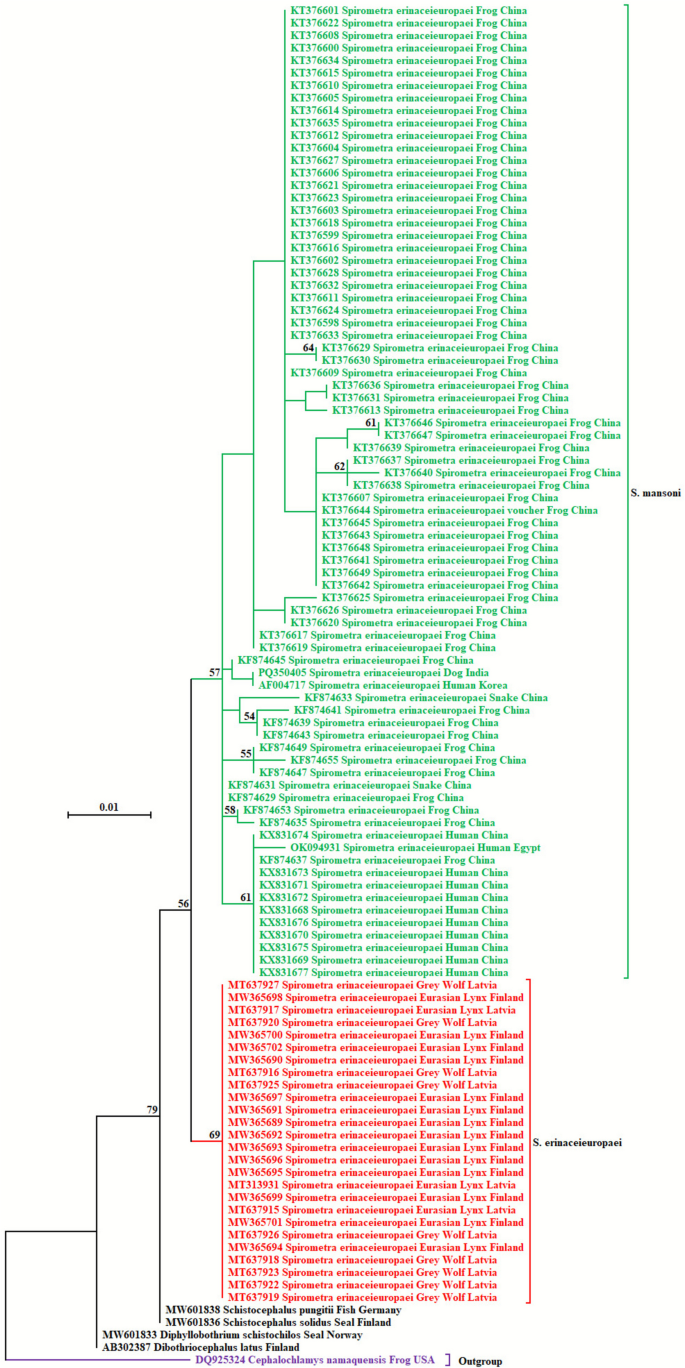

In this study, phylogenetic analysis of S. erinaceieuropaei labelled sequences (n = 104) in nucleotide databases revealed two distinct clades (Fig. 2). The larger clade comprised sequences from Asian and African countries (99.24–100% identity), including China (n = 75), Korea (n = 1), India (n = 1; present study), and Egypt (n = 1), which these days have been reclassified as S. mansoni, while the smaller clade consisted of European sequences (100% identity) from Latvia (n = 12) and Finland (n = 14), which is labelled as true S. erinaceieuropaei. The isolates included in this study were revisited and classified according to the most recent taxonomy, which is presented in Table 1.

Fig. 2

Phylogenetic analysis of Spirometra sequences based on the partial 28S rRNA gene using the maximum likelihood method and Jukes-Cantor model. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The taxon name of each sequence is depicted by the accession number, followed by the names of the parasite and host, and the country of origin. The colour coding of the different sequences is as follows. The green and red taxon names represent the S. mansoni and S. erinaceieuropaei sequences. The default black taxon names indicate sequences of related pseudotapeworms available in the GenBank. Meanwhile, a purple taxon name is used to mark an outgroup species

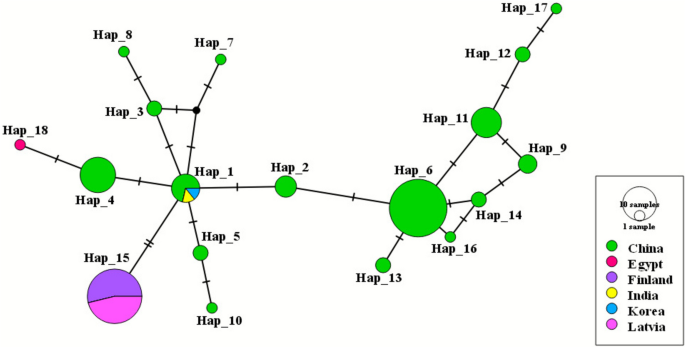

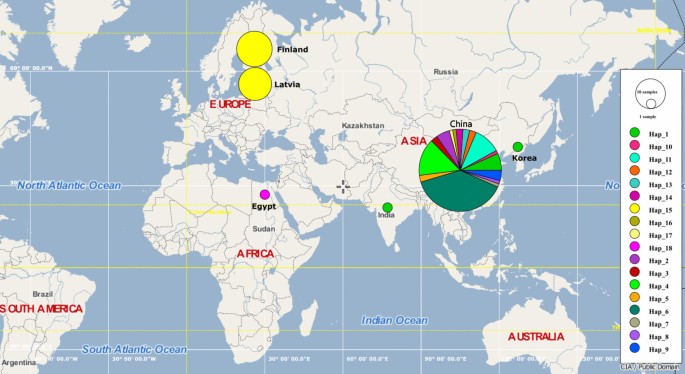

Haplotype analysis of the 104 sequences identified 18 distinct haplotypes (Table 2). The European Spirometra isolates exhibited no genetic variation and formed a single haplotype (Hap_15). Within the haplotype network (Fig. 3), Hap_1 occupied a central position, suggesting it was a likely ancestral haplotype from which several others diverged. Asian haplotypes were separated from each other by a single mutational step. Hap_6 (n=29) and Hap_15 (n=26) had the highest frequencies, followed by Hap_4 (n = 11). The interior placement and multiple connections of Hap_1 and Hap_6 suggested they were older haplotypes, while peripheral haplotypes likely represented more recent variants that arose through mutation. The distribution of haplotypes by location is illustrated in the world map (Fig. 4).

Table 2 Details of Spirometra spp. haplotypes generated in this study

Fig. 3

Location-wise median-joining haplotype network of Spirometra spp. based on the partial 28S rRNA gene constructed using PopART. Each circle represents a unique haplotype and the size of the circle is proportional to the number of sequences included. Nucleotide variations are denoted by the hatch marks across the lines connecting the haplotypes with each bar representing a single nucleotide variation. A colour code to the country of origin is given

Fig. 4

Map depicting the geographical distribution of 18 haplotypes of Spirometra spp. based on the partial 28S rRNA gene

Molecular diversity indices, neutrality tests and mismatch distribution of Spirometra populations

The Asian Spirometra population (S. mansoni) showed high haplotype diversity (Hd = 0.82) and moderate nucleotide diversity (π = 0.007), while the European Spirometra population (S. erinaceieuropaei) did not show any haplotype and nucleotide diversities. All neutrality tests (Fu’s Fs, Fu and Li’s D, Fu and Li’s F, and Tajima’s D) for the Asian population yielded negative but statistically non-significant results (Table 3), suggesting possible recent population expansion. Mismatch distribution analysis supported this proposition, with low raggedness index and Ramos-Onsins and Rozas’ R2, although the moderate mean absolute error indicated that the expansion may not be uniform across populations.

Table 3 Molecular diversity indices, neutrality tests, and mismatch distribution of different Spirometra spp. haplotypes within described populations

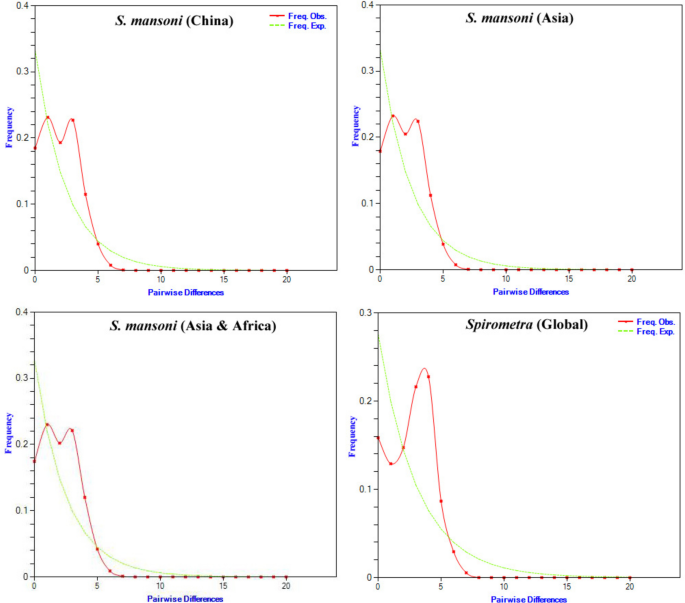

The mismatch distribution of the global Spirometra population showed a unimodal pattern with a small bump at the start, likely caused by the European population’s low genetic diversity and single haplotype. This suggested the global population comprised genetically distinct subgroups, with the European group contributing to the early bump and the structured Asian group adding to the main peak (Fig. 5). The neutrality tests and R2 statistic were non-significant, indicating no strong support for recent expansion or selective pressure. Although the low raggedness index aligned with an expansion model, the results likely reflected a globally structured population with heterogeneous diversity rather than a single expanding lineage. These results suggest that the Spirometra population has a complex demographic history, potentially influenced by population structure, gene flow, or other evolutionary forces, rather than a single, recent expansion event.

Fig. 5

Representation of the observed and expected mismatch-distribution of the Spirometra populations and overall dataset based on the partial 28S rRNA gene

The pairwise Fst value between the Asian and African Spirometra populations indicated a moderate level of genetic differentiation (Fst = 0.7817), but this was not statistically significant (Table 4). Although the result suggested genetic separation and restricted gene flow (Nm = 0.13963), the small sample size or random variation may have contributed to the observed differentiation, making it uncertain whether it reflects true genetic separation.

Table 4 Gene flow and genetic differentiation of continent wise S. mansoni populations

The AMOVA revealed that 78.17% of the variation occurred between continents, while 21.83% occurred within populations. The significant Fst value indicated that the genetic differentiation between populations was not due to random variation (Table 5). The AMOVA results highlighted strong geographic structuring in Spirometra populations, with most variation explained by continental differences. This, along with the significant Fst, suggested restricted gene flow, possible host-associated divergence, and the presence of distinct evolutionary lineages, particularly in Asia, where intra-population diversity was also high.

Table 5 Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) of continent wise S. mansoni populations

The Mantel test performed on continent-wise S. mansoni populations revealed weak positive correlation (r = 0.149) between genetic and geographic distances among S. mansoni isolates, but it was not statistically significant (p = 0.055). However, when isolates from both S. mansoni and S. erinaceieuropaei populations were included, the Mantel test revealed a positive and statistically significant correlation (r = 0.5918, p = 0.001), suggesting that genetic differentiation between the two species was partially explained by geographic distance, consistent with isolation by distance.

Discussion

Recent research by Kuchta et al. (2024) proposed seven distinct lineages of Spirometra, addressing longstanding taxonomic ambiguities. Molecular approaches, particularly coxI and 28S rRNA gene amplification, proved reliable for species differentiation due to morphological similarities. Accurate species-level identification was crucial given the zoonotic significance of sparganosis and limited reporting in India. This clarification enhanced diagnostic precision, resolved taxonomic uncertainties, and improved understanding of host distribution and occurrence, ultimately informing assessments of the impact on human and animal health.

The 28S rRNA gene, containing both conserved and variable regions, is a widely used nuclear marker in phylogenetic studies for species differentiation in parasitic helminths, including Spirometra spp. (Lee et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2014). As coxI sequencing of the isolate was unsuccessful, comparative analysis was restricted to 28S rRNA sequences of S. erinaceieuropaei and S. mansoni available globally. Sequences from other Spirometra species were not included due to their absence in GenBank.

According to Kuchta et al. (2024), two Spirometra species, S. mansoni and S. asiana, were found to be circulating in Asia. Several Spirometra isolates previously identified by Zhang et al. (2016) and Tang et al. (2017) were reclassified as S. mansoni based on the coxI gene analysis, and their corresponding 28S rRNA sequences were included in the phylogenetic analysis in this study. Furthermore, isolates from China, Korea, India, and Egypt for which only 28S rRNA data were available were also included in this study. The maximum likelihood tree, based on 28S rRNA, revealed two distinct clades (S. mansoni and S. erinaceieuropaei). The results indicated a broader distribution of S. mansoni across Asia and Africa, while S. erinaceieuropaei appeared to be restricted to Europe. These findings supported the statement by Kuchta et al. (2021, 2024) that most Spirometra species have specific geographical patterns, except for S. mansoni, which is widespread.

According to the haplotype network analysis, S. mansoni haplotypes from Asia (China, India, and Korea) and Africa (Egypt) were widely distributed and exhibited high genetic variability, generating 17 haplotypes. This pattern likely reflected geographic subdivision and long-term divergence of S. mansoni populations. The findings aligned with those of Yamasaki et al. (2021), who constructed a haplotype network based on coxI sequences from Spirometra isolates across Asia and identified two distinct species, later designated as S. mansoni and S. asiana (Yamasaki et al. 2024). Spirometra mansoni exhibited greater genetic diversity, likely due to the presence of cryptic lineages that had diverged over a long evolutionary timescale. In contrast, S. erinaceieuropaei sequences from Europe (Finland and Latvia) displayed a single shared haplotype with no detectable intraspecific variation, consistent with the findings of Bagrade et al. (2021), who also reported no variability in European 28S rDNA sequences of S. erinaceieuropaei. According to Bazsalovicsová et al. ([2022](/article/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8#ref-CR5 "Bazsalovicsová EČ, Radačovská A, Lavikainen A, Kuchta R, Králová-Hromadová I (2022) Genetic interrelationships of Spirometraerinaceieuropaei (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidea), the causative agent of sparganosis in Europe. Parasite 29:8. https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2022009

")), the _coxI_ based _S. erinaceieuropaei_ haplotype network exhibited a distinct star-like pattern, with shared haplotypes across Finland, Latvia, and Poland, and no clear geographic structure, supporting the existence of a Baltic lineage.The analysis of the Asian Spirometra population (China, India, and Korea) in this study revealed high haplotype diversity and low nucleotide diversity, indicating a population with diverse haplotypes but relatively low sequence divergence. This pattern was consistent with a previous study for Asian populations based on coxI sequences (Yamasaki et al. 2021). Similarly, Zhang et al. (2016) reported high haplotype diversity within Chinese Spirometra populations based on concatenated sequences of cytb, coxI, rrnS, and 28S rDNA.

Notable differences emerged when neutrality test results were compared. Zhang et al. (2016) reported non-significant positive values for Tajima’s D and Fu’s F tests in the total Chinese population, interpreting this as evidence against recent population expansion. In contrast, the neutrality tests in this study yielded non-significant negative values, suggesting a possible excess of rare variants. This pattern may have indicated a recent population expansion or reflected regional variation, gene flow, or shared ancestry that differentially influenced population structure. The differing results could also be attributed to the genetic markers used: 28S rRNA in our study versus the more rapidly evolving coxI gene used by Zhang et al. (2016), which may have captured recent demographic events more effectively. Global analysis of Spirometra populations from Asia, Africa, and Europe revealed negative neutrality values and a unimodal mismatch distribution, suggesting population expansion. These results were consistent with Hong et al. (2020), which analyzed a large global dataset of Spirometra coxI sequences and found evidence of population expansion and a structured global population.

Our analysis of the Chinese S. mansoni population revealed a bimodal mismatch distribution and non-significant negative neutrality indices, suggesting demographic structure. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2016) observed two clades and a dispersed haplotype network within Chinese populations. However, the studies differed in mismatch distribution patterns and neutrality values, likely due to the use of different genetic markers (28S rRNA vs coxI). In both the current study and that of Zhang et al. (2016), AMOVA indicated greater genetic variation among populations than within them, with continent-wise variation (between Asia and Africa) accounting for 78.17% in the present study and 57.31% among Chinese subpopulations as reported by Zhang et al. (2016). The combined evidence from our study and previous research indicated that S. mansoni populations exhibited genetic diversity and structure. The greater genetic variation among populations than within populations pointed to geographic barriers limiting gene flow between Spirometra populations across continents, resulting in significant genetic structuring.

Conclusion

This study used 28S rRNA sequences to analyze global Spirometra diversity and identified two major clades: S. mansoni in Asia and Africa, and S. erinaceieuropaei in Europe. Spirometra mansoni showed high haplotype diversity and low nucleotide diversity, suggesting long-term divergence and cryptic lineages, while S. erinaceieuropaei exhibited minimal diversity, with a single haplotype detected across European isolates. The study suggested population expansion and emphasized the need for further research using multi-marker approaches and expanded sampling to better understand Spirometra genetics. This study confirmed the presence of S. mansoni in India, clarified its global spread, and can inform public health strategies to mitigate zoonotic transmission risks.

Data availability

All the nucleotide sequences generated and used in the present study are available in the GenBank. The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

- Adolph CB, Peregrine AS (2021) Tapeworms. In: Greene’s infectious diseases of the dog and cat. WB Saunders, pp 1455–1484

- Badri M, Olfatifar M, KarimiPourSaryazdi A, Zaki L, Madeira de Carvalho LM, Fasihi Harandi M, Barikbin F, Madani P, Vafae Eslahi A (2022) The global prevalence of Spirometra parasites in snakes, frogs, dogs, and cats: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vet Med Sci 8(6):2785–2805

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bagrade G, Králová-Hromadová I, Bazsalovicsová E, Radačovská A, Kołodziej-Sobocińska M (2021) The first records of Spirometra erinaceieuropaei (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidae), a causative agent of human sparganosis, in Latvian wildlife. Parasitol Res 120(1):365–371

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Bandelt H, Forster P, Röhl A (1999) Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 16(1):37–48

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bazsalovicsová EČ, Radačovská A, Lavikainen A, Kuchta R, Králová-Hromadová I (2022) Genetic interrelationships of Spirometra erinaceieuropaei (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidea), the causative agent of sparganosis in Europe. Parasite 29:8. https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2022009

Article Google Scholar - Bowman DD (2021) Diagnostic parasitology. In: Georgis’ parasitology for veterinarians, 11th edn. WB Saunders, pp 349–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-54396-5.00016-7

- Chen SY, Gong TF, He JL, Li F, Li WC, Xie LX, Xie XR, Liu YS, Zhou YF, Liu W (2022) Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of Spirometra tapeworms from snakes in Hunan Province. Vet Sci 9(2):62

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Daly JJ (1981) Sparganosis. In: Beran GW (ed) Steele JH. Parasitic zoonoses, CRC Press, Boca Raton, CRC handbook series in zoonoses. Section C, pp 293–312

Google Scholar - Eom KS, Park H, Lee D, Choe S, Kang Y, Bia MM, Ndosi BA, Nath TC, Eamudomkarn C, Keyyu J, Fyumagwa R (2019) Identity of Spirometra theileri from a leopard (Panthera pardus) and spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) in Tanzania. Korean J Parasitol 57(6):639

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Excoffier L, Lischer H (2011) Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour 11:564–567

Google Scholar - Faust EC, Campbell HE, Kellogg CR (1929) Morphological and biological studies on the species of Diphyllobothrium in China. Am J Epidemiol 9(3):560–583

Article Google Scholar - Fraija-Fernández N, Waeschenbach A, Briscoe AG, Hocking S, Kuchta R, Nyman T, Littlewood DTJ (2021) Evolutionary transitions in broad tapeworms (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidea) revealed by mitogenome and nuclear ribosomal operon phylogenetics. Mol Phylogenet Evol 163:107262.

- Hernández-Orts JS, Scholz T, Brabec J, Kuzmina T, Kuchta R (2015) High morphological plasticity and global geographical distribution of the Pacific broad tapeworm Adenocephalus pacificus (syn. Diphyllobothrium pacificum): molecular and morphological survey. Acta Trop 149:168–178

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hong X, Liu SN, Xu FF, Han LL, Jiang P, Wang ZQ, Cui J, Zhang X (2020) Global genetic diversity of Spirometra tapeworms. Trop Biomed 37(1):237–250

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hudson RR, Slatkin M, Maddison WP (1992) Estimation of levels of gene flow from DNA sequence data. Genetics 132:583–589

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jeon HK, Eom KS (2019) Mitochondrial DNA sequence variability of Spirometra species in Asian countries. Korean J Parasitol 57(5):481

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jeon HK, Park H, Lee D, Choe S, Kang Y, Bia MM, Lee SH, Sohn WM, Hong SJ, Chai JY, Eom KS (2018) Genetic and morphologic identification of Spirometra ranarum in Myanmar. Korean J Parasitol 56(3):275

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jukes TH, Cantor CR (1969) Evolution of protein molecules. In: Munro HN (ed) Mammalian protein metabolism. Academic Press, New York, pp 21–132

- Kamo H (1999) Guide to identification of Diphyllobothriid cestodes. Gendai Kikaku, Tokyo, Japan

- Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD (2019) MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform 20:1160–1166

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kavitha KT, Latha BR, Bino Sundar ST, Sridhar R, Abdul Basith S (2014) Sparganosis in Russell’s viper snake: a case report. J Parasit Dis 38(4):394–395

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kuchta R, Scholz T (2017) Diphyllobothriidea Kuchta, Scholz, Brabec & Bray, 2008. In: Caira JN, Jensen K (eds) Planetary biodiversity inventory (2008–2017): Tapeworms from Vertebrate Bowels of the Earth. University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, pp 167–189

- Kuchta R, Kołodziej-Sobocińska M, Brabec J, Młocicki D, Sałamatin R, Scholz T (2021) Sparganosis (Spirometra) in Europe in the molecular era. Clin Infect Dis 72(5):882–890

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kuchta R, Phillips AJ, Scholz T (2024) Diversity and biology of Spirometra tapeworms (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidea), zoonotic parasites of wildlife: a review. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl 24:100947

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kumar S, Stecher G, Suleski M, Sanderford M, Sharma S, Tamura K (2024) MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis version 12 for adaptive and green computing. Mol Biol Evol 41(12):msae263

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Le AT, Do LQT, Nguyen HBT, Nguyen HNT, Do AN (2017) Case report: the first case of human infection by adult of Spirometra erinaceieuropaei in Vietnam. BMC Infect Dis 17:1–4

Article Google Scholar - Lee SU, Chun HC, Huh S (2007) Molecular phylogeny of parasitic Platyhelminthes based on sequences of partial 28S rDNA D1 and mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I. Korean J Parasitol 45(3):181

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Leigh JW, Bryant D (2015) PopART: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol Evol 6(9):1110–1116

Article Google Scholar - Liu Q, Li MW, Wang ZD, Zhao GH, Zhu XQ (2015) Human sparganosis: a neglected food borne zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis 15:1226–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00133-4

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Liu W, Gong T, Chen S, Liu Q, Zhou H et al (2022) Epidemiology, diagnosis, and prevention of sparganosis in Asia. Animals 12(12):1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12121578

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lynch M, Crease TJ (1990) The analysis of population survey data on DNA sequence variation. Mol Biol Evol 7(4):377–394

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Moudgil AD, Nehra AK (2025) Mitochondrial genetic markers based phylogenetic analyses of Hyalomma dromedarii Koch, 1844 (Acari: Ixodidae). J Genet Eng Biotechnol 23(1):100460

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Mueller JF (1974) The biology of Spirometra. J Parasitol 60:3–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/3278670

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Nawa Y, Tanaka M, Yoshikawa M (2024) Sparganosis in the Indian sub-continent and the Middle East. Parasites Hosts Dis 62(3):263

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Omar HM, Fahmy M, Abuowarda M (2023) Hand palm sparganosis: Morphologically and genetically confirmed Spirometra erinaceieuropaei in a fourteen-year-old girl. Egypt. J Parasitol Dis 47:859–864

Article Google Scholar - Pal MG, Chakrabarti A, Pramanik AK, Pradhan KK, Chatterjee A (1981) Spirometrid tapeworm in a mongrel dog. Indian J Anim Health 20(1):71–72

Google Scholar - Patnaik MM, Acharjyo LN (1970) Notes on the helminth parasites of vertebrates in Baranga Zoo (Orissa). Indian Vet J 47(9):723–730

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Rathore A, Padmanabha H, Mahale R, Arora A, Goyal A, Reddy J, Sipani M, Pruthi N, Lingaraju TS, Nagarathna S, Yasha TC (2024) Cerebral sparganosis–an unusual parasitic infection mimicking cerebral tuberculosis: isolation of a live plerocercoid larva of Spirometra mansoni. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 27(4):443–447

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Rozas J, Ferrer-Mata A, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Guirao-Rico S, Librado P, Ramos-Onsins SE, Sánchez-Gracia A (2017) DnaSP v6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol Biol Evol 34(12):3299–3302

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Saleque A, Juyal PD, Bhatia BB (1990) Spirometra sp. in a domestic cat in India. Vet Parasitol 35(3):273–276

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Scholz T, Kuchta R, Brabec J (2019) Broad tapeworms (Diphyllobothriidae), parasites of wildlife and humans: recent progress and future challenges. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl 9:359–369

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Soulsby EJL (1982) Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domestic animals. 7th edn. Elsevier, Reed Elsevier India Private Limited, New Delhi, pp 131

- Tang TH, Wong SS, Lai CK, Poon RW, Chan HS, Wu TC, Cheung YF, Poon TL, Tsang YP, Tang WL, Wu AK (2017) Molecular identification of Spirometra erinaceieuropaei tapeworm in cases of human sparganosis, Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis 23(4):665

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Vettorazzi R, Norbis W, Martorelli SR, García G, Rios N (2023) First report of Spirometra (Eucestoda; Diphyllobothriidae) naturally occurring in a fish host. Folia Parasitol 70:8. https://doi.org/10.14411/fp.2023.008

Article CAS Google Scholar - Wardle RA, Mac Leod JA, Radinovsky S (1974) Advances in the zoology of tapeworms. University of Minnesota Press, pp 1950–1970

- Yamasaki Y, Morishima H, Sugiyama H (2017) Cestode infections in Japan. IASR 38:74–76

Google Scholar - Yamasaki H, Sanpool O, Rodpai R, Sadaow L, Laummaunwai P, Un M, Thanchomnang T, Laymanivong S, Aung WPP, Intapan PM, Maleewong W (2021) Spirometra species from Asia: genetic diversity and taxonomic challenges. Parasitol Int 80:102181

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Yamasaki H, Sugiyama H, Morishima Y, Kobayashi H (2024) Description of Spirometra asiana sp. nov. (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidae) found in wild boars and hound dogs in Japan. Parasitol Int 98:102798

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Yoshikawa M, Ouji Y, Nishiofuku M, Ishizaka S, Nawa Y (2010) Sparganosis cases reported in Japan in the recent decade, 2000–2009. Clin Parasitol 21:33–36

Google Scholar - Zhang X, Jing CU, Liu LN, Tong WEI, Jiang P, Wang ZQ (2014) Phylogenetic location of the Spirometra sparganum isolates from China, based on sequences of 28S rDNA D1. Iran J Parasitol 9(3):319

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhang X, Cui J, Liu LN, Jiang P, Wang H, Qi X, Wu XQ, Wang ZQ (2015a) Genetic structure analysis of Spirometra erinaceieuropaei isolates from central and southern China. PLoS One 10(3):e0119295

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhang X, Wang H, Cui J, Jiang P, Fu GM, Zhong K, Zhang ZF, Wang ZQ (2015b) Characterisation of the relationship between Spirometra erinaceieuropaei and Diphyllobothrium species using complete cytb and cox1 genes. Infect Genet Evol 35:1–8

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Zhang X, Wang H, Cui J, Jiang P, Lin ML, Zhang YL, Liu RD, Wang ZQ (2016) The phylogenetic diversity of Spirometra erinaceieuropaei isolates from southwest China revealed by multi genes. Acta Trop 156:108–114

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Director of Research and the Dean, College of Veterinary Sciences, Lala Lajpat Rai University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Hisar, Haryana, India, for providing the necessary facilities to carry out the research. Authors are also thankful to Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY) – Remunerative Approaches for Agriculture and Allied Sector Rejuvenation (RAFTAAR) and Anusandhan National Research Foundation (ANRF) for enriching the department with the facilities which were utilized during this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding.

Author information

Author notes

- Anil Kumar Nehra and Rasmita Panda have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Veterinary Parasitology, Lala Lajpat Rai University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Hisar, 125004, Haryana, India

Anil Kumar Nehra & Aman Dev Moudgil - Division of Parasitology, ICAR- Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatnagar, Bareilly, 243122, Uttar Pradesh, India

Rasmita Panda - Department of Veterinary Parasitology, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel University of Agriculture and Technology, Meerut, 250110, Uttar Pradesh, India

Prem Sagar Maurya - Department of Veterinary Medicine, College of Veterinary Science, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Rampura Phul, 151103, Punjab, India

Ansu Kumari

Authors

- Anil Kumar Nehra

- Rasmita Panda

- Prem Sagar Maurya

- Ansu Kumari

- Aman Dev Moudgil

Contributions

Anil Kumar Nehra: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing, Supervision. Rasmita Panda: Original draft preparation, Investigation, Methodology. Prem Sagar Maurya: Investigation, Writing—review and editing. Ansu Kumari: Methodology, Investigation, Software, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing. Aman Dev Moudgtil: Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence toAnil Kumar Nehra.

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Una Ryan

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

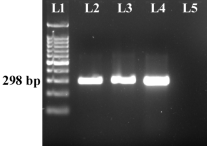

Sup. Figure 1

PCR amplification of the partial 28S rRNA of S. mansoni indicated the presence of ~298 bp amplicon [Lane 1: DNAmark 100 bp DNA ladder (G-Biosciences); Lanes 2, 3: Positive test samples; Lane 4: Positive template control; Lane 5: Negative template control] (PNG 109 KB)

High Resolution Image (TIF 1110 KB)

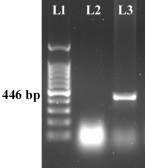

Sup. Figure 2

PCR amplification of the coxI gene of S. mansoni indicated the presence of ~446 bp amplicon [Lane 1: DNAmark 100 bp DNA ladder (G-Biosciences); Lane 2: Negative template control; Lane 3: Positive test sample] (PNG 81.1 KB)

High Resolution Image (TIF 841 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nehra, A.K., Panda, R., Maurya, P.S. et al. Deciphering the global genetic structure of Spirometra mansoni and S. erinaceieuropaei based on 28S ribosomal RNA: Insights into taxonomical revaluation and population dynamics.Parasitol Res 124, 135 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8

- Received: 24 July 2025

- Accepted: 05 November 2025

- Published: 20 November 2025

- Version of record: 21 November 2025

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-025-08589-8