A decontamination strategy for resolving SARS-CoV-2 amplicon contamination in a next-generation sequencing laboratory (original) (raw)

Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) amplicon contamination was discovered due to next-generation sequencing (NGS) reads mapping in the negative controls. Environmental screening was undertaken to determine the source of contamination, which was suspected to be evaporation during polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays while using the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) ARTIC protocol. A decontamination strategy is hereby documented to assist laboratories that may experience similar amplicon contamination. Routine molecular laboratory environmental screening as a quality control is highly recommended.

Introduction

Reverse-transcribed and amplified viral sequences (amplicons) are a well-known contamination issue in molecular laboratories [1,2,3,4,5]. Amplicons are generated at a very high copy number during PCR (up to 1013 molecules/reaction), posing a significant risk to any molecular investigation due to ensuing carryover contamination [6]. As SARS-CoV-2 research efforts gain unprecedented momentum worldwide, amplicon contamination can prove very disruptive, with precious time and energy diverted to resolving the contamination rather than performing productive research. False-positive results caused by amplicon contamination can jeopardize the efficacy of public health policies, public health responses, surveillance programs, and restriction measures to control the pandemic. The current COVID-19 pandemic has put many molecular diagnostic and research laboratories under exceptional pressure to provide surveillance results, potentially leading to underestimating, ignoring, or even neglecting potential amplicon contamination. Therefore, regular screening for amplicon contamination in the laboratory environment to identify the sources and minimize amplicon contamination is crucial to rule out compromised results. Here, we suggest some useful monitoring and decontamination strategies undertaken after uncovering SARS-CoV-2 amplicon contamination during routine laboratory screening.

Materials and methods

Identifying the source of amplicon contamination

After the receipt of extracted SARS-CoV-2 RNA from diagnostic laboratories, the NGS laboratory in context was involved in cDNA generation and whole-genome sequencing. Prior to routine environmental screening, evaporation of amplicons during PCR reactions due to the high denaturation temperature (98 °C) in the ARTIC SARS-CoV-2 sequencing protocol had occurred and was suspected to be the cause of the amplicon contamination. Swabbing of the surfaces in and around the thermocyclers appeared to confirm this, although other potential sources could not be ruled out.

Procedure for decontamination of environmental surfaces

A decontamination strategy was implemented twice daily for five weeks. First, all the instruments and equipment in the laboratory were covered with sterile plastic bags. Then 75% ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was sprayed on the ceiling, walls and in the air and left for 30 minutes. Fresh 0.5% sodium hypochlorite (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) solution was prepared for each use [7] and used to decontaminate the laboratory surfaces such as benches and shelves and left for 30 minutes. Racks were immersed in 0.5% sodium hypochlorite (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) solution for 10 minutes. Afterwards, double-distilled water from a Direct-Q® 3UV Water Purification System (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was used to clean the surfaces, followed by spraying with 75% ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and wiping with paper towels. The laboratory equipment (pipettes and thermocyclers) was wiped with absolute ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and later with DNA Decontamination Reagent (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Extraction of RNA

After each decontamination process, swabs were taken from over 15 different parts and surfaces of the laboratory using sterile medical-grade polyurethane swabs (Cleansafe Labs, Cape Town, South Africa). Swabs were stroked in an ‘S’ shape, both vertically and diagonally. The swab was then cut and placed in a 2-ml cryogenic vial (Corning, MA, USA) containing saline buffer solution (Adcock Ingram, Johannesburg, South Africa). Automated RNA extraction was performed using a NUCLISENS EASYMAG instrument (Biomerieux, Marcy I’Etoile, France) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

qPCR assay

Primers and probes from a TaqPath™ COVID-19 CE-IVD RT-PCR Kit, targeting three SARS-CoV-2 genes (S, N, and ORF1ab) were utilized to perform a qPCR assay using QuantStudio 7 (Thermo Fisher, Oregon, USA). The limit of detection of the molecular assay was set at a cycle threshold (Ct) value of 37.

Results

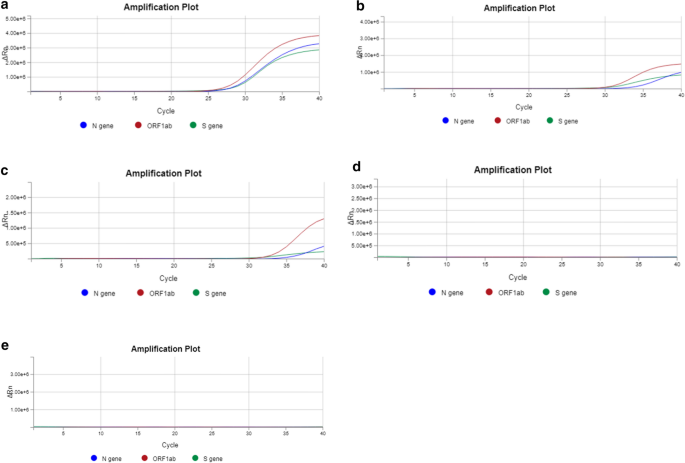

The qPCR reports were recorded to evaluate the effectiveness of the decontamination strategy (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The positive control was a sample from a patient who had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 with a nadir in Ct values in the range of 24.74-28.12, 23.60-27.91, and 23.60-27.79 for the N, S, and ORF1ab gene, respectively. The sensitivity for the S and ORF1ab genes was higher (lower Ct values) than for the N gene, potentially due to suboptimally designed RT-PCR primers for the N gene. Elution buffer (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) was used as a negative control, and no amplification signal was detected during RT-PCR. To ensure that our cut swabs were contamination-free, we also included a cut swab as an additional negative control, which also did not produce an amplification signal. Amplicons were found at high titers (Ct < 37) on several objects and surfaces, including thermocyclers, pipettes, bench surfaces, doorknobs, a laboratory calculator, and PCR cabinets (Table 1). A decreasing trend in amplicon contamination detection was observed over the course of the five weeks of decontamination. Amplicon contamination was still persistent in the fourth week on four of the 19 surfaces that were swabbed (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Intriguingly, we observed fluctuation between positive and negative results on two surfaces: the DNA quantification bench and the outer surface of a -20 °C DNA storage freezer (Table 1). However, after including a DNase decontamination reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as part of the decontamination routine in the fifth week, we observed notable elimination of the amplicons on all of the swabbed surfaces (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). A graphical representation of the real-time PCR data was captured, and fifteen out of the nineteen surfaces (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1) that were swabbed showed no amplicon contamination by the fourth week (Fig. 1).

Table 1 Reported Ct values for laboratory surfaces swabbed for SARS-CoV-2 amplicon contamination

Fig. 1

Representative standard qPCR curves indicating the presence/absence of contamination on the swabbed surface general DNA bench. On the _y_-axis, Rn is the fluorescence of the reporter dye divided by the fluorescence of a passive reference dye. In this view, Rn is plotted against the PCR cycle number on the _x_-axis. Three SARS-CoV-2 genes – N, S, and ORF1ab – were targeted for amplicon contamination. Panels a to e represent the first to the fifth week of screening, respectively.

Discussion

An effective amplicon decontamination routine using 0.5% sodium hypochlorite, distilled water, 75% ethanol (absolute ethanol for equipment), and DNA decontamination reagent is reported. We screened over 15 different laboratory surfaces, as a small amount of an amplified PCR product that infiltrates laboratory equipment or is present in aerosols can easily spread throughout the lab. While amplicon contamination of surfaces such as benches, shelves, and laboratory equipment such as pipettes and thermocyclers is often easily detectable, it may require looking beyond the obvious to identify other contaminated objects that could easily be overlooked. From our experience, such objects may include items such as laboratory armchairs, calculators, doorknobs, timers, and more importantly, the bottles containing the reagents (ethanol and sodium hypochlorite) used for decontamination. Furthermore, different laboratory surfaces are colonized differently by the amplicons, explaining why it took somewhat longer to fully eliminate amplicons on some surfaces than others.

Any suspicions of co-evaporation of DNA with water during PCR, as has been reported by laboratory practitioners, should be treated with extreme caution. Co-evaporation of DNA with water during PCR has been demonstrated to occur in a previous study, regardless of seal type and pre-heating the thermocycler lids, resulting in cross-contamination arising from migration of DNA from well to well [8]. The use of mineral oil and paraffin wax has been proposed previously as a strategy to avoid false-positive PCR results [9,10,11]. Alternatively, 8-cap strips can be used as a seal type.

While focusing on decontaminating laboratory surfaces is essential, contaminated reagent kits can be a potential contamination source. Contamination arising from reagent production has been reported recently and has raised concerns [12,13,14]. Whether contamination occurs during the preparation of reagents or in the laboratory, negative controls provided in the test kit, as well as in-house laboratory controls such as elution buffer and nuclease-free water should show no amplification [15]. Once the kit is opened, reagents should be stored in aliquots in sterile containers. Additionally, careful handling and storage are imperative to prevent contamination of reagent boxes and aliquots. Non-sterile handling with the same gloves used for other laboratory activities should be avoided.

Additionally, personal protective equipment (PPE) should always be worn during laboratory work. When moving from one area of the laboratory to another (e.g., from the pre- to post-PCR area), the full set of PPE should be changed and the workflow strictly adhered to. If possible, different colors of PPE may be used in different areas of the laboratory. Laboratory practitioners and the cleaning staff should be reminded that laboratory guidelines necessitate unidirectional workflow, therefore, they should regard each section of the laboratory as a compartmentalized room to avoid amplicon transfer, especially for non-compartmentalized molecular laboratories, which could be more prone to contamination. Gloves should be sterilized frequently with 70% ethanol and changed when moving against the direction of flow to prevent cross-contamination but preferably changed for each compartment. The PPE should be removed in a manner that avoids contact with external surfaces and disposed of in a dedicated waste container. This should be followed by washing hands with soap and water or sanitizing with 70% alcohol solution. Further guidelines, as provided by WHO for working with SARS-CoV-2 samples, should be followed [[16](/article/10.1007/s00705-022-05411-z#ref-CR16 "World Health Organization (2020) Laboratory biosafety guidance related to coronavirus disease (COVID-19). [Online]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/laboratory-biosafety-guidance-related-to-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)

. Accessed 7 Aug 2020")\]. It is essential to be cognizant of the potential for amplicon contamination by implementing quality control screening measures. Regular screening of the laboratory environment is essential to monitor amplicon contamination and prevent false-positive results.References

- Kwok SA, Higuchi R (1989) Avoiding false positives with PCR. Nature 339(6221):237–238

Article CAS Google Scholar - Borst A, Box ATA, Fluit AC (2004) False-positive results and contamination in nucleic acid amplification assays: suggestions for a prevent and destroy strategy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 23(4):289–299

Article CAS Google Scholar - Speers DJ (2006) Clinical applications of molecular biology for infectious diseases. Clin Biochem Rev 27(1):39

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Champlot S, Berthelot G, Pruvost M, Bennett EA, Grange T, Geigl EM (2010) An efficient multistrategy DNA decontamination procedure of PCR reagents for hypersensitive PCR applications. PLoS ONE 5(9):e13042

Article Google Scholar - Davidi D, Fitzgerald S, Glaspell HL, Jalbert S, Maheras S, Mattoon SE, Britto VM, Hamer DH, Nguyen GT, Platt J, Stuopis CW (2020) Amplicon contamination in labs masquerades as COVID19 in surveillance tests. medRxiv 2020:2

Google Scholar - Pruvost M, Grange T, Geigl EM (2005) Minimizing DNA contamination by using UNG-coupled quantitative real-time PCR on degraded DNA samples: application to ancient DNA studies. Biotechniques 38(4):569–575

Article CAS Google Scholar - Loh TP, Horvath AR, Wang CB, Koch D, Adeli K, Mancini N, Ferrari M, Hawkins R, Sethi S, Lippi G (2020) Operational considerations and challenges of biochemistry laboratories during the COVID-19 outbreak: an IFCC global survey. Clin Chem Lab Med 58(9):1441–1449

Article Google Scholar - Stals A, Werbrouck H, Baert L, Botteldoorn N, Herman L, Uyttendaele M, Van Coillie E (2009) Laboratory efforts to eliminate contamination problems in the real-time RT-PCR detection of noroviruses. J Microbiol Methods 77(1):72–76

Article CAS Google Scholar - Sparkman DR (1992) Paraffin wax as a vapor barrier for the PCR. Genome Res 2(2):180–181

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hébert B, Bergeron J, Potworowski EF, Tijssen P (1993) Increased PCR sensitivity by using paraffin wax as a reaction mix overlay. Mol Cell Probes 7(3):249–252

Article Google Scholar - Rijpens NP, Herman LM (2002) Molecular methods for identification and detection of bacterial food pathogens. J AOAC Int 85(4):984–995

Article CAS Google Scholar - Huggett JF, Benes V, Bustin SA, Garson JA, Harris K, Kammel M, Kubista M, McHugh TD, Moran-Gilad J, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW (2020) Cautionary note on contamination of reagents used for molecular detection of SARS-CoV-2. Clin Chem 66(11):1369–1372

Article Google Scholar - Mögling R, Meijer A, Berginc N, Bruisten S, Charrel R, Coutard B, Eckerle I, Enouf V, Hungnes O, Korukluoglu G, Kossyvakis T (2020) Delayed laboratory response to COVID-19 caused by molecular diagnostic contamination. Emerg Infect Dis 26(8):1944

Article Google Scholar - Lagerborg KA, Normandin E, Bauer MR, Adams G, Figueroa K, Loreth C, Gladden-Young A, Shaw B, Pearlman L, Shenoy ES, Hooper D (2021) DNA spike-ins enable confident interpretation of SARS-CoV-2 genomic data from amplicon-based sequencing. bioRxiv 21:863

Google Scholar - van Zyl G, Maritz J, Newman H, Preiser W (2019) Lessons in diagnostic virology: expected and unexpected sources of error. Rev Med Virol 29(4):e2052

Article Google Scholar - World Health Organization (2020) Laboratory biosafety guidance related to coronavirus disease (COVID-19). [Online]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/laboratory-biosafety-guidance-related-to-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19). Accessed 7 Aug 2020

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the engagement with Dr. Andre de Kock, Dr. Jeniffer Giandhari, and Prof. O’Neill HG on how to effectively perform amplicon de-contamination.

Funding

This work was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (African Enteric Viruses Genome Initiative grant number BMGF OPP1180423_2017). Other funding grants awarded to M.M.N. that funded this research include: South Africa Medical Research Council (self-initiated research grant), WHO, grant number 2017/757922-0; the National Research Foundation (competitive programme for rated researchers, grant number 120814) and Poliomyelitis Research Foundation (grant number 19/16 and grant number 21/77). The views and opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the funding and affiliated institutions but solely those of the authors of this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Next Generation Sequencing Unit and Division of Virology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, 9300, South Africa

Peter Mwangi, Milton Mogotsi, Ayodeji Ogunbayo, Teboho Mooko, Wairimu Maringa, Hlengiwe Sondlane, Kelebogile Nkwadipo, Olusesan Adelabu & Martin Nyaga - Division of Virology, National Health Laboratory Service and University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

Philip Armand Bester & Dominique Goedhals - Pathcare Vermaak, Pretoria, 0157, South Africa

Dominique Goedhals

Authors

- Peter Mwangi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Milton Mogotsi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ayodeji Ogunbayo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Teboho Mooko

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Wairimu Maringa

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hlengiwe Sondlane

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kelebogile Nkwadipo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Olusesan Adelabu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Philip Armand Bester

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Dominique Goedhals

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Martin Nyaga

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by PM, MM, AO, PAB, and MN. The first draft of the manuscript was written by PM, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence toMartin Nyaga.

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

This study was approved under ethics number HSD2020/1860/2710 by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Carolina Scagnolari.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mwangi, P., Mogotsi, M., Ogunbayo, A. et al. A decontamination strategy for resolving SARS-CoV-2 amplicon contamination in a next-generation sequencing laboratory.Arch Virol 167, 1175–1179 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-022-05411-z

- Received: 15 November 2021

- Accepted: 27 January 2022

- Published: 17 March 2022

- Issue Date: April 2022

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-022-05411-z