Comparative study of clinical outcomes between laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy (LAPG) and laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) for proximal gastric cancer (original) (raw)

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the most common cancer in Korea, annually affecting more than 25,000 patients [[1](/article/10.1007/s10120-012-0178-x#ref-CR1 "

http://www.cancer.go.kr/cms/statics/incidence/index.html#4

. Accessed 1 Dec 2011.")\]. The proportions of early gastric cancer (EGC) and proximal gastric cancer have increased continuously over the past 20 years, from 24.8 % to nearly 50 % and from 5.3 to 14.0 %, respectively. Proximal EGC accounted for 30.3 % of all proximal gastric cancers, whereas distal EGC accounted for 51.5 % of all distal gastric cancers \[[2](/article/10.1007/s10120-012-0178-x#ref-CR2 "Ahn HS, Lee HJ, Yoo MW, Jeong SH, Park DJ, Kim HH, Kim WH, Lee KU, Yang HK. Changes in clinicopathological features and survival after gastrectomy for gastric cancer over a 20-year period. Br J Surg. 2011;98(2):255–60.")–[4](/article/10.1007/s10120-012-0178-x#ref-CR4 "The information Committee of the Korean Gastric Cancer Association. 2004 Nationwide gastric cancer report in Korea. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2007;7(1):47–54.")\]. Accordingly, more surgeons now favor laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy (LAG) as an option for the treatment of EGC.For distal EGC, laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) has already gained acceptance because it is minimally invasive and is therefore a suitable alternative to open surgery. Many studies have reported early results of LADG’s safety and short-term benefits [5–7]. In 2015, the long-term results of the KLASS trial will be reported. The trial is the first phase III, multicenter, prospective, randomized trial of LAG versus open gastrectomy [8]. By the time that these results are reported, it is expected that LADG will have become the standard surgical approach for distal EGC, replacing open surgery8.

However, for proximal EGC, there are few reports comparing laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy (LAPG) with laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy (LATG). This is because LAPG is a technically demanding procedure and proximal gastrectomy is associated with a high incidence of reflux esophagitis and anastomotic stenosis. In fact, approximately 16.2–61.5 % of patients who undergo proximal gastrectomy subsequently experience reflux symptoms. Because of this frustrating complication, the optimal extent of resection for proximal gastric cancer is controversial, even in open surgery [9–12]. The purpose of this study was to assess the feasibility, safety, and surgical and functional outcomes of LAPG and LATG in patients with proximal gastric cancer. To our knowledge, this is the first report on the outcomes of LAPG versus those of LATG.

Patients and methods

Patients

Between June 2003 and December 2009, at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, 131 patients underwent laparoscopy-assisted proximal or total gastrectomy for upper-third gastric adenocarcinoma of clinical stage I (cT1 N0 M0 or cT2 N0 M0, according to the seventh edition of the International Union against Cancer Classification). The choice of surgical approach, LATG or LAPG, was at the discretion of the surgeons and patients. If the tumor size was relatively large, the volume of remnant stomach was too small to perform esophagogastrostomy and gain some functional benefit from LAPG, and therefore in such cases, we performed LATG. There were 50 patients in the LAPG group and 81 in the LATG group.

Evaluation of clinical parameters

The clinical characteristics of the patients (e.g., sex, age, tumor size, histological type, length of resection margin, number of retrieved and metastatic lymph nodes), early postoperative complications (0–30 days), late postoperative complications (30 days onward), and overall survival of the patients were analyzed based on the information obtained from our prospectively collected gastric cancer database. Changes in biochemical data were analyzed according to the extent of gastrectomy at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after the surgery. The patients were routinely followed up at our outpatient clinic at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively and annually thereafter. Anastomotic stenosis and reflux symptoms were diagnosed based on the endoscopic findings and symptoms. If the patients complained of dysphagia during the postoperative follow up and if a 9-mm-diameter endoscope could not pass through the esophagojejunostomy or esophagogastrostomy, anastomotic stenosis was diagnosed. Reflux symptoms were diagnosed by modified Visick scores at postoperative month 12 (Table 1). Because 24-h pH monitoring and gastric emptying scans were not performed in the LATG group, comparative data were not available for these measures. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital (No. B-1106/129-111).

Table 1 Visick score

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed with SPSS statistical software version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were compared using the Pearson χ 2 test, and continuous variables were compared using Student’s _t_-test. All the values are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. Survival curves were calculated, using the life-table method and Gehan–Wilcoxon method, for the 2 study groups (in months) from the primary surgical treatment to the final follow up or death. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Surgical approach

Laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy

The patients were placed under general anesthesia in the supine Trendelenburg position. The surgeon and camera operator sat on the patient’s right, and the assistant sat on the patient’s left. Pneumoperitoneum was then established using an open technique, and 5 working ports were created: three 5-mm working ports on the left upper quadrant and the right upper quadrant, one 10-mm working port infraumbilically, and one 12-mm working port on the edge of the right rectus muscle. The omentum was mobilized approximately 4 cm inferior to the gastroepiploic arcade. The left gastroepiploic vessels were ligated distal to the omental branch and divided using hemoclips. The omentum was dissected from the mesocolon. The right gastroepiploic vessels were carefully preserved. The peritoneum along the superior portion of the pancreas was mobilized. The left lobe of the liver was retracted using a combined suture retraction of the faliciform ligament [13]. The lesser omentum was mobilized, with careful preservation of the right gastric vessels and hepatic branch of the left vagus nerve. The hepatic and pyloric branches of the vagus nerves were preserved routinely. The dissection proceeded along lymph node stations 7, 8a, and 9. The coronary vein and left gastric artery were then hemoclipped and divided. The dissection proceeded along lymph node stations 11p and 11d, up to the splenic hilum. The esophagogastric junction was mobilized and transected using a linear stapler. The dissection was carried out by the “downstream method” to dissect lymph node stations 2 and 4sa. A 4-cm transverse incision was made in the upper abdomen.

Reconstruction (end-to-end anastomosis)

An extracorporeal esophagogastrostomy was created through a mini-laparotomy using a purse-string clamp and circular stapler. The esophagogastrostomy was created between the esophagus and the posterior wall of the remnant stomach through the resection opening. After the completion of the esophagogastrostomy, the opening was closed with a linear stapler.

Reconstruction (side-to-side anastomosis)

Gastric tube formation was completed extracorporeally with linear staplers resecting the lesser curvature side. The gastric tube size was approximately 15 × 4 cm. The intracorporeal side-to-side esophagogastric anastomosis was completed using a linear stapler. The gastric tube was placed in the abdominal cavity posterior to the esophagus. The common entry hole was closed using continuous/interrupted sutures. The esophagus was anchored to the hiatus, an important step to reduce reflux symptoms (esophagopexy). The esophagopexy located the esophagogastric anastomosis in the abdominal cavity, not in the mediastinum, where it would be under negative pressure. Hiatal repair was the final step. An esophagopexy and hiatal repair were done in all the late-phase LAPG cases (i.e., those performed between October 2007 and November 2009).

Laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy

In addition to the LAPG procedure, the following procedures were added for LATG: the right gastric and gastroepiploic vessels were divided at their origins, and lymph node stations 5, 6, and 14v (optional) were dissected. The duodenum was transected 2 cm distal to the pylorus, using a laparoscopic linear stapler. After the dissection, the stomach was removed. The usual extracorporeal Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy with jejunojejunostomy through a mini-laparotomy was performed.

Results

Patients’ demographics and clinical characteristics

The clinical characteristics of all the patients are provided in Table 2. The two groups were comparable with regard to age, sex, body mass index, postoperative hospital stay, median follow up, and gross and histological tumor types. The time of solid food initiation was similar in the two groups, at 5.7 days after the operation. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in the postoperative hospital stay (11.5 ± 6.2 vs. 10.0 ± 6.7 days) or median follow-up time (44.0 ± 17.9 vs. 38.3 ± 21.6 months).

Table 2 Demographics and surgical characteristics of patients undergoing LAPG and LATG

Surgical and pathological outcomes

In the comparison of the surgical characteristics, the mean operation time was shorter in the LAPG group than in the LATG group (216.3 ± 56.0 vs. 242.2 ± 52.5 min, p = 0.009). The estimated blood loss was lower in the LAPG group than in the LATG group (115.8 ± 81.9 vs. 181.7 ± 138.0 ml, p = 0.002; Table 2). There were 13 cases of end-to-end esophagogastrostomy (EEEG) and 37 cases of side-to-side esophagogastrostomy (SSEG) in the LAPG group. All the LATG reconstructions were done by the usual extracorporeal Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy.

The 2 groups were similar in terms of tumor depth and lymph node metastasis status. However, the mean lesion size was larger (4.0 ± 2.7 vs. 2.8 ± 1.3 cm) and the number of retrieved lymph nodes was higher in the LATG group (47.4 ± 17.3 vs. 33.1 ± 13.8). The proximal resection margin (4.4 ± 2.3 cm vs. 3.5 ± 2.3 cm) and distal resection margin (14.3 ± 4.2 cm vs. 4.0 ± 1.6 cm) were longer in the LATG group (Table 3).

Table 3 Comparison of pathological characteristics

Early complications and postoperative mortality (0–30 days)

Early complications occurred in 12 patients (24.0 %) in the LAPG group and 14 patients (17.3 %) in the LATG group; there were no statistically significant differences in early complications between the 2 groups (Table 4).

Table 4 Postoperative course

Late complications (>30 days)

Late complications occurred in 22 patients (44.0 %) in the LAPG group. They consisted of reflux symptoms (n = 16, 32 %) and anastomotic stenosis (n = 6, 12.0 %). For the LATG group, late complications were observed in 18 patients (22.2 %) and included anastomotic stenosis (n = 4), reflux symptoms (n = 3), anemia (n = 3), ileus (n = 6), internal hernia (n = 1), and intussusception (n = 1). The overall late complication rate after LATG was significantly lower than that after LAPG (p < 0.001; Table 4).

Reflux symptoms were the main complications after LAPG and occurred in 32.0 % of the patients in the LAPG group, whereas anastomotic stenosis occurred in 12.0 % of the LAPG group. In the LATG group, 4.9 % of the patients experienced anastomotic stenosis, a rate not significantly different from that of the LAPG group (p = 0.139). However, the rate of reflux symptoms was significantly higher in the LAPG group (p < 0.001). We reoperated on 4 patients owing to severe reflux symptoms that were medically intractable (Visick grade IV). Laparoscopic pyloroplasty was performed in 2 patients whose gastric emptying scans showed delayed gastric emptying time (1,083 and 206 min, respectively; reference range 70–150 min), and we performed remnant total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy in 2 patients whose gastric emptying scans showed normal gastric emptying time and a positive Bernstein test result, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5 Incidence of reflux symptoms

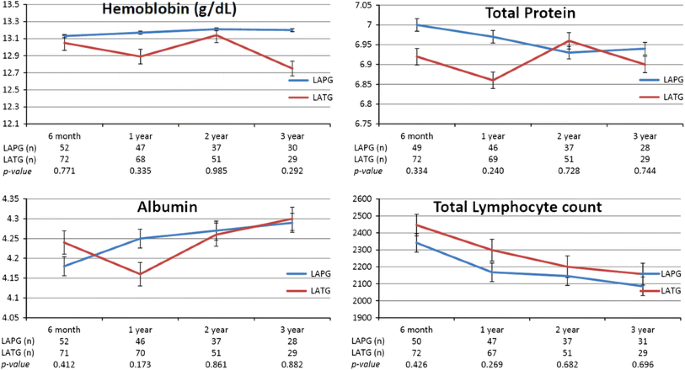

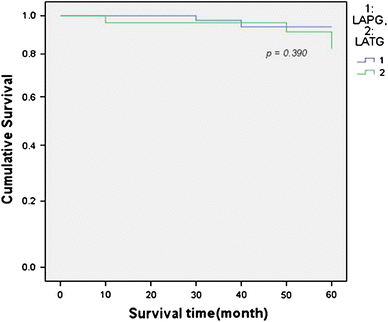

Nutritional status and survival

The parameters of nutritional status (i.e., serum hemoglobin, total protein, albumin, total leukocyte count, and body weight) were not significantly different in the 2 groups (Fig. 1). Overall survival was similar in the 2 groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1

Parameters of nutritional status. LAPG laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy, LATG laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy

Fig. 2

Overall survival

Comparison of morbidity according to method of anastomosis

Reconstruction after LAPG was of 2 types: EEEG in 13 cases and SSEG in 37 cases. According to the reconstruction method (EEEG or SSEG), there were no significant differences in the early complication rate (15.4 vs. 27.0 %, respectively; p = 0.398) or reflux symptoms (15.4 vs. 37.8 %, respectively; p = 0.135). However, the incidence of anastomotic stenosis was significantly higher with EEEG than with SSEG (46.2 vs. 0 %, p < 0.001; Table 6).

Table 6 Comparison of morbidity according to method of anastomosis

Comparison of perioperative outcomes and morbidity according to the SSEG phase

The SSEG patients were classified into subgroups (phases) according to the serial order in which the procedures were performed. The early, middle, and late phases were October 2004 to December 2005, May 2006 to September 2007, and October 2007 to November 2009, respectively, and there were 12, 12, and 13 patients, respectively in these groups. In the late-phase group, all the patients received antireflux procedures such as esophagopexy with hiatal repair. The mean operation time and postoperative stay were significantly shorter and the early complication rates showed a trend toward being reduced in the late-phase group. The rate of reflux symptoms decreased from the early to the late phase, but the decrease was not statistically significant. In the late-phase group, there were no patients with a Visick score of IV (Table 7), and in this group body weight loss was significantly less than that in the LATG patients.

Table 7 Comparison of perioperative outcome and morbidity according to the phase of side-to-side esophagogastrostomy (SSEG)

Discussion

This study shows that LAPG is a feasible and safe technique in terms of operative time, estimated blood loss, number of resected lymph nodes, early complication rate, and oncologic outcomes. However, the late complication rate, especially for reflux symptoms and anastomotic stricture, was sufficiently high that, as with other studies, we cannot conclude that LAPG is a good alternative to LATG.

In our study, esophagogastrostomy was performed using the same reconstruction method as that used in open proximal gastrectomy. Because there were no significant differences in the reconstruction method between laparoscopic and open proximal gastrectomy, it is reasonable that the rates of reflux symptoms and anastomotic stenosis in our study were similar to those seen in other studies [10, 11]. The functional outcomes after LAPG also failed to show a benefit for proximal gastrectomy.

However, when we focused on patients in the late phase of SSEG after LAPG, the late complication rate was acceptable, with significantly less body weight loss compared with that in the LATG patients, owing to the antireflux procedures performed (esophagopexy with hiatal repair).

Proximal gastric cancer, because of its aggressiveness, is usually diagnosed at a more advanced stage of the disease than distal gastric cancer [14]. This is one of most important reasons for the unpopularity of proximal gastrectomy in the open gastrectomy era. However, the proportion of proximal EGC has recently increased in Korea owing to mass screening and advances in diagnostic tools. In regard to proximal EGC and the concept of minimally invasive surgery, LAPG has theoretical advantages over the other treatment options (i.e., open proximal gastrectomy, open total gastrectomy, and LATG). In the 2010 Japanese Gastric Cancer Guidelines, proximal gastrectomy is classified as a modified surgery, which can be done in EGC, except for the indication of endoscopic submucosal dissection.

However, open total gastrectomy is still regarded as the standard method for proximal EGC in Korea and other countries. When the prognosis of EGC and the quality of life after surgery is taken into consideration, however, open total gastrectomy may be excessive. If it can be performed, LATG is a better option than open total gastrectomy owing to its lesser degree of invasiveness. However, LATG is not a popular procedure for proximal EGC in Korea and Japan because of the difficulties of creating an esophagojejunostomy under laparoscopy. The number of cases of LATG has been increasing in Korea (20 cases in 2003, 112 cases in 2004, and 231 cases in 2008). In comparison, LAPG has been performed rarely. Among patients having open gastrectomy, proximal gastrectomy was performed only in 141 patients (1.0 %) in 2009 [3]. When considering the advantages of a minimally invasive surgery and function-preserving procedures, LAPG is theoretically a better option than LATG. Many functional benefits have been reported for LAPG, including improved nutrition, prevention of anemia, improved release of gut hormones, and a reduction of postoperative complaints [15, 16]. Oncologic concerns also have been solved, to some degree; several reports of proximal gastrectomy have shown long-term oncologic outcomes similar to those for total gastrectomy even in advanced disease [17]. However, most gastric surgeons are reluctant to perform proximal gastrectomy because of the 2 well-established complications: reflux and anastomotic stricture [9, 16].

To overcome the reflux symptoms, various reconstruction methods have been developed. Esophagogastrostomy is the simplest procedure for reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy, but it has a high postoperative risk of reflux symptoms and anastomotic stricture [10, 18]. Modification through esophagogastrostomy after proximal gastrectomy to date has shown disappointing results in the rates of reflux symptoms and anastomotic stricture [10]. Katsoulis and colleagues [19] reported that 100 % of patients experienced reflux symptoms after proximal gastrectomy, and Kim and associates [18] also reported high rates of reflux esophagitis (48 %). Esophagogastrostomy with antireflux procedures could be an acceptable approach if the surgeon has sufficient experience in proximal gastrectomy. However, the procedure is complicated, requiring a high degree of experience and training, and therefore has not been popular after LAPG.

The reason for the higher incidence of anastomotic stricture in patients undergoing proximal gastrectomy than in those undergoing total gastrectomy is not known, but the proposed mechanisms are causation by reflux esophagitis and the discrepancy in wall thickness between the esophagus and stomach. Endoscopic balloon dilatation has proven to be a well-tolerated and effective treatment. However, the incidence of anastomotic stricture is so high that a major modification of the esophagogastrostomy method is thought to be needed to allow relatively inexperienced surgeons to perform this laparoscopic surgery.

A good alternative to esophagogastrostomy reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy is esophagojejunostomy, such as that done with jejunal interposition or double-tract reconstruction. To prevent reflux esophagitis, various esophagojejunostomy techniques after proximal gastrectomy have been studied, including jejunal interposition [20], in which a segment of the jejunum is interposed between the esophagus and the remnant stomach, and jejunal pouch interposition [21], in which a jejunal pouch is used instead. Katai and colleagues [22] reported the long-term results of jejunal interposition after proximal gastrectomy, and the incidence of reflux symptoms remained low (5.5 %), a similar finding to those of previous studies but a lower rate than that observed after other types of proximal gastrectomy. Their incidence of reflux symptoms was similar to that after total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y (5.0 %) [22]. However, these procedures for reconstruction are thought to be technically complex under laparoscopy.

The present study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study. Second, 2 kinds of reconstruction methods were used in the LAPG subgroups, meaning that the overall LAPG group was heterogeneous. Third, after surgery, the quality of life was not assessed using a validated questionnaire (such as the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Stomach 22 or the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index). Fourth, there may have been some bias in comparing the early phase of EEEG and the late phase of SSEG. However, to our knowledge, this study is the first report comparing LAPG with LATG. This study therefore provides important basic data on the use of LAPG in the era of minimally invasive and function-preserving surgery.

In conclusion, LAPG is technically feasible and oncologically acceptable for the treatment of proximal gastric cancer but requires a high degree of surgical experience. LAPG with esophagogastrostomy reconstruction is associated with an increased risk of reflux symptoms even with the use of antireflux procedures (i.e., vagus nerve preservation and esophagopexy with hiatal repair). With further accumulation of experience, late complications such as reflux symptoms and anastomotic stricture may be less of an obstacle. LAPG appeared to offer no nutritional benefit overall, but in the late phase of LAPG, it seemed that there were some functional benefits for nutrition.

LAPG could be the criterion standard method in the treatment of proximal gastric cancer if the rates of reflux esophagitis and anastomotic stricture were to be as low as those seen with LATG. The SSEG with antireflux procedures used in this study could be a good approach but, unfortunately, requires a great deal of technical training and surgical experience. Simpler procedures such as double-tract reconstruction are considered to be appropriate for reconstruction after LAPG. A well-designed, prospective, randomized study is needed to analyze and validate the functional and treatment outcomes of different surgical procedures for proximal gastric cancer.

References

- http://www.cancer.go.kr/cms/statics/incidence/index.html#4. Accessed 1 Dec 2011.

- Ahn HS, Lee HJ, Yoo MW, Jeong SH, Park DJ, Kim HH, Kim WH, Lee KU, Yang HK. Changes in clinicopathological features and survival after gastrectomy for gastric cancer over a 20-year period. Br J Surg. 2011;98(2):255–60.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Jeong O, Park Y-K. Clinicopathological features and surgical treatment of gastric cancer in South Korea: the results of 2009 nationwide survey on surgically treated gastric cancer patients. J Gastric Cancer. 2011;11(2):69–77.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - The information Committee of the Korean Gastric Cancer Association. 2004 Nationwide gastric cancer report in Korea. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2007;7(1):47–54.

Google Scholar - Hosono S, Arimoto Y, Ohtani H, Kanamiya Y. Meta-analysis of short-term outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(47):7676–83.

PubMed Google Scholar - Lee JH, Han HS. A prospective randomized study comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer: early results. Surg Endosc. 2005;19(2):168–73.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Adachi Y, Suematsu T, Shiraishi N, Katsuta T, Morimoto A, Kitano S, Akazawa K. Quality of life after laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 1999;229(1):49–54.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kim HH, Hyung WJ, Cho GS, Kim MC, Han SU, Kim W, Ryu SW, Lee HJ, Song KY. Morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an interim report–a phase III multicenter, prospective, randomized trial (KLASS Trial). Ann Surg. 2010;251(3):417–20.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hoshikawa T, Denno R, Ura H, Yamaguchi K, Hirata K. Proximal gastrectomy and jejunal pouch interposition: evaluation of postoperative symptoms and gastrointestinal hormone secretion. Oncol Rep. 2001;8(6):1293–9.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - An JY, Youn HG, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Kim S. The difficult choice between total and proximal gastrectomy in proximal early gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2008;196(4):587–91.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Yoo CH, Sohn BH, Han WK, Pae WK. Long-term results of proximal and total gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma of the upper third of the stomach. Cancer Res Treat. 2004;36(1):50–5.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hsu CP, Chen CY, Hsieh YH, Hsia JY, Shai SE, Kao CH. Esophageal reflux after total or proximal gastrectomy in patients with adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(8):1347–50.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Shabbir A, Lee JH, Lee MS, Park do J, Kim HH. Combined suture retraction of the falciform ligament and the left lobe of the liver during laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(12):3237–40.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Piso P, Werner U, Lang H, Mirena P, Klempnauer J. Proximal versus distal gastric carcinoma—what are the differences? Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7(7):520–5.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Adachi Y, Inoue T, Hagino Y, Shiraishi N, Shimoda K, Kitano S. Surgical results of proximal gastrectomy for early-stage gastric cancer: jejunal interposition and gastric tube reconstruction. Gastric Cancer. 1999;2(1):40–5.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Takeshita K, Saito N, Saeki I, Honda T, Tani M, Kando F, Endo M. Proximal gastrectomy and jejunal pouch interposition for the treatment of early cancer in the upper third of the stomach: surgical techniques and evaluation of postoperative function. Surgery. 1997;121(3):278–86.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Harrison LE, Karpeh MS, Brennan MF. Total gastrectomy is not necessary for proximal gastric cancer. Surgery. 1998;123(2):127–30.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kim JH, Park SS, Kim J, Boo YJ, Kim SJ, Mok YJ, Kim CS. Surgical outcomes for gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach. World J Surg. 2006;30(10):1870–6 (discussion 1877–1878).

Google Scholar - Katsoulis IE, Robotis JF, Kouraklis G, Yannopoulos PA. What is the difference between proximal and total gastrectomy regarding postoperative bile reflux into the oesophagus? Dig Surg. 2006;23(5–6):325–30.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Uyama I, Sugioka A, Fujita J, Komori Y, Matsui H, Hasumi A. Completely laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition and lymphadenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191(1):114–9.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Tomita R, Fujisaki S, Tanjoh K, Fukuzawa M. A novel operative technique on proximal gastrectomy reconstructed by interposition of a jejunal J pouch with preservation of the vagal nerve and lower esophageal sphincter. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48(40):1186–91.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Katai H, Morita S, Saka M, Taniguchi H, Fukagawa T. Long-term outcome after proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition for suspected early cancer in the upper third of the stomach. Br J Surg. 2010;97(4):558–62.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar