Outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for differentiated-type early gastric cancer with histological heterogeneity (original) (raw)

Introduction

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is currently recognized as one of the main treatment options for early gastric cancer (EGC) because of its minimal invasiveness and comparable survival to open gastrectomy in selected cases [1]. Currently, ESD is indicated only for EGC with differentiated histology diagnosed based on forceps biopsy specimens [1]. However, it is not uncommon to find a mixture of undifferentiated component (UC) with differentiated EGC during histopathological review of ESD specimen including the entire EGC lesion (Fig. 1). In Korean and Japanese guidelines, EGC consisting of components of both differentiated- and undifferentiated-type carcinoma is classified according to the quantitatively predominant histological type [2, 3]. Therefore, differentiated-type-predominant EGC mixed with UC accounting for less than 50 % (MUC-EGC) is currently regarded as differentiated EGC. However, as the prognostic relevance of the proportion of each component has not been established, it remains controversial whether MUC-EGC can be managed in the same way as pure differentiated-type EGC (PuD-EGC).

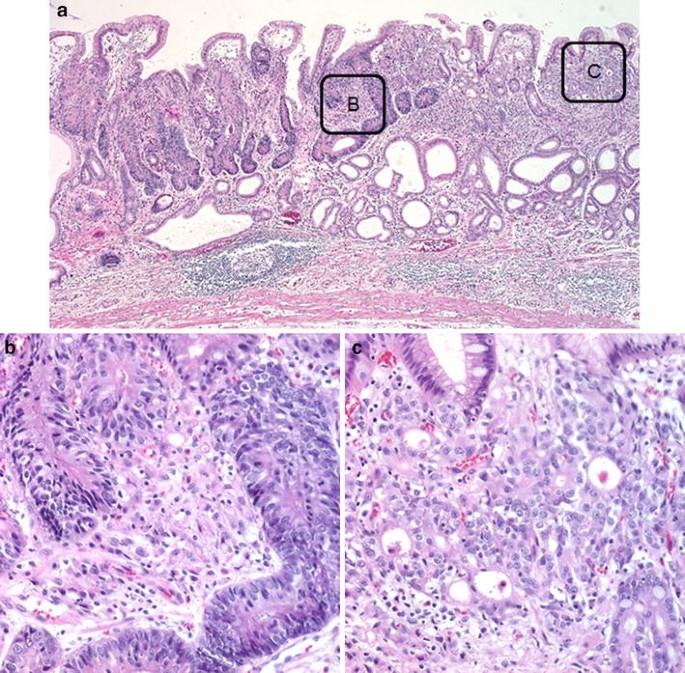

Fig. 1

Representative case of differentiated-type-predominant early gastric cancer mixed with undifferentiated component. a Low-power view of endoscopic submucosal dissection specimen showing heterogeneous histology from moderately differentiated to poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). ×40. b Higher magnification of poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma. H&E. ×400. c Higher magnification of moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma. H&E. ×400

Several previous studies analyzed the risk of lymph node (LN) metastasis in surgically resected EGCs with histological heterogeneity. For EGC with submucosal invasion, Mita and Shimoda [4] and Hanaoka et al. [5] reported that the rate of LN metastasis was higher in MUC-EGC than in PuD-EGC (27.4 % versus 7.0 % and 19.2 % versus 5.4 %, respectively). For EGC confined within the mucosal layer, Takizawa et al. [6] also reported that the rate of LN metastasis was higher in MUC-EGC compared to PuD-EGC (11.1 % versus 3.1 %). However, no cases of LN metastasis were observed in either of these studies [4–6], if MUC-EGC met the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications proposed by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association [1, 2, 7]. These consistent results from surgical series showed the minimal risk of LN metastasis in MUC-EGC cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications and suggested that ESD might be indicated for these cases [4–6]. However, the role and appropriate indication of ESD for MUC-EGC remain controversial [2]. This controversy is largely the result of the lack of long-term outcomes data after ESD for MUC-EGC [2]. Therefore, a large-scale study including long-term follow-up data is definitely required to establish the role and appropriate indication of ESD for MUC-EGC. To the best of our knowledge, however, there has been no large-scale study evaluating the long-term outcomes after ESD for differentiated-type EGC with histological heterogeneity.

In the present study we aimed to elucidate clinicopathological features of MUC-EGC compared to PuD-EGC. In addition, we analyzed the long-term outcomes after ESD using a large database to investigate the role and appropriate indication of ESD for MUC-EGC.

Methods

Patients

Patients who underwent their first ESD for differentiated-type EGC (well-or moderately differentiated EGC or papillary EGC) at Samsung Medical Center between April 2007 and June 2011 were enrolled in this study. Patients who underwent ESD and were finally diagnosed to have undifferentiated-type EGC (poorly differentiated EGC or signet ring-cell EGC) were excluded from the study population. During the study period, 1,577 differentiated-type EGC lesions in 1,527 consecutive patients were treated by ESD at our institution. We performed a retrospective review of short-term endoscopic outcomes and long-term follow-up data after ESD of these 1,527 consecutive patients identified from a prospectively collected database. All ESD procedures for EGC were performed by three experienced endoscopists (B.H.M., J.H.L., J.J.K.) based on the expanded indications. At our institution, ESD is not indicated for undifferentiated-type EGC. When pathological review of the forceps biopsy specimen revealed undifferentiated-type EGC, patients were recommended to undergo radical gastrectomy and were excluded from the study population. When pathological review of the ESD specimen revealed the presence of UC in contrast to the pre-ESD diagnosis of differentiated-type EGC based on the forceps biopsy specimen, the tumor was regarded as differentiated EGC if UC accounted for less than 50 % of the tumor area. Among 1,577 differentiated-type EGC treated by ESD, 1,408 cases were finally diagnosed as PuD-EGCs and 169 cases were diagnosed as MUC-EGCs with UC less than 50 %. At our institution, MUC-EGC is managed in the same way as PuD-EGC after ESD.

The ESD procedure of our institution has been described in detail elsewhere [8, 9]. In brief, ESD consists of three steps: (1) injecting fluid into the submucosal layer to separate it from the proper muscle layer; (2) circumferential cutting of the mucosa surrounding the lesion; and (3) submucosal dissection of the connective tissue under the lesion. All enrolled patients provided written informed consent before undergoing ESD. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Samsung Medical Center.

Histopathological evaluation

ESD specimens were stretched, pinned to a polystyrene plate, and totally immersed in 10 % neutral buffered formalin for more than 12 h for fixation. After fixation, the specimen was sectioned serially at 2-mm intervals parallel to a line that included the closest resection margin of the specimen so that both lateral and vertical margins could be assessed. The depth of tumor invasion was then evaluated along with lymphovascular involvement and degree of differentiation [1]. Histology was classified into differentiated adenocarcinoma (well- or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma or papillary adenocarcinoma) or undifferentiated adenocarcinoma (poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma or signet ring-cell carcinoma). According to Korean and Japanese guidelines, EGC consisting of components of both differentiated- and undifferentiated-type carcinoma was classified according to the quantitatively predominant histological type [2, 3]. In our study, MUC-EGC was defined when pathological review of the whole resected EGC specimen revealed UC less than 50 %. PuD-EGC was defined when pathological review of the whole resected EGC specimen showed the absence of UC [4]. All ESD specimens were prospectively and independently reviewed by two experienced pathologists specializing in gastrointestinal pathology (K.M.K. and C.K.P.). In cases of discrepancy between two pathologists, consensus was reached after discussion.

Definition

En bloc resection was defined as resection of the tumor in one piece with endoscopically no residual tumor. R0 resection was defined as resection of the tumor with no histological evidence of tumor on the lateral and vertical margins. The resection was considered as curative when all the following conditions were fulfilled: well- or moderately differentiated EGC or papillary EGC, en bloc resection or piecemeal resection with successful reconstruction, negative lateral resection margins, negative vertical resection margin, and no lymphovascular invasion: (1) tumor size ≤2 cm, mucosal cancer; (2) tumor size >2 cm, mucosal cancer, no ulcer in tumor; (3) tumor size ≤3 cm, mucosal cancer, ulcer in tumor; or (4) tumor size ≤3 cm, SM1 cancer (submucosal invasion depth <500 μm from muscularis mucosa layer). Local recurrence was defined when the cancer was detected at the primary resection site in follow-up esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in cases where pathological review of the ESD specimen had revealed no tumor on the lateral and vertical margins. During the study period, a total of 14 patients underwent additional ESD or argon plasma coagulation (APC) within 1 week after the initial ESD because of undetermined or definite tumor involvement of the resection margin (6 ESDs and 5 APCs for PuD-EGC and 3 ESDs for MUC-EGC). For all 14 cases, no remnant tumor was endoscopically or histologically detected after the additional procedure, and these cases were included when calculating the curative resection and local recurrence rate [10]. The following patients were excluded from calculating the local recurrence rate: (1) patients undergoing gastrectomy after ESD; (2) patients not undergoing immediate and complete additional endoscopic treatment after ESD in case of undetermined or definite tumor involvement of the resection margin; and (3) patients not undergoing follow-up examination after ESD. If a new EGC lesion was detected at a site other than the primary resection area in follow-up EGD within 12 months after ESD, it was regarded as a synchronous lesion. In case of a new EGC lesion at a site other than the primary resection area 12 months or more after ESD, it was defined as a metachronous recurrence.

Follow-up after ESD

EGD with a biopsy was performed 2 months after ESD to confirm the healing of the ESD-induced artificial ulcer and to exclude the presence of any residual tumor. EGD and abdominal computed tomography (CT) were performed every 6 months thereafter for 3 years to detect local, metachronous, or extragastric recurrence. From the fourth to fifth year after ESD, EGD and abdominal CT were performed annually.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data analysis was conducted using the χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous data were analysed using the Student’s t test or Mann–Whitney U test. Data on overall survival were obtained using the national registry of medical insurance. Overall survival was measured from the date of ESD to the date of death from any cause or to the censoring date of October 31, 2013. Median duration of follow-up after ESD was 48 months (range, 5–78 months). Overall survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and were analyzed by the log-rank test with SPSS software (version 21.0). The following patients were excluded from calculating the overall survival rate: (1) patients undergoing gastrectomy after ESD; (2) patients not undergoing immediate and complete additional endoscopic treatment after ESD in case of undetermined or definite tumor involvement of the resection margin; (3) patients with multiple EGCs; and (4) patients not undergoing follow-up examination after ESD. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathological features and ESD outcomes of MUC-EGC compared to PuD-EGC

During the study period, 1,577 differentiated-type EGC lesions (1,408 PuD-EGCs and 169 MUC-EGCs) in 1,527 patients were treated by ESD. MUC-EGC accounted for 10.7 % (169/1,577) of all EGCs enrolled in this study. Among 169 cases of MUC-EGC, 162 (95.9 %) were mixed with poorly differentiated histology, and only 7 cases (4.1 %) had a signet ring-cell carcinoma component.

Table 1 summarizes the clinicopathological features of PuD-EGC and MUC-EGC. MUC-EGC was significantly associated with larger tumor size, more frequent submucosal invasion, moderately differentiated histology, lymphovascular invasion, and tumor involvement of resection margin compared to PuD-EGC. En bloc resection, R0 resection, and en bloc with R0 resection rates in MUC-EGC cases were 94.1 %, 84.0 %, and 81.7 %, respectively, and those in PuD-EGC cases were 97.3 %, 95.4 %, and 93.8 %, respectively (P = 0.021 for en bloc resection rate; P < 0.001 for R0 resection rate; P < 0.001 for en bloc with R0 resection rate). Bleeding and perforation rates in MUC-EGC cases were 3.0 % and 5.3 %, respectively, and those in PuD-EGC cases were 4.2 % and 2.4 %, respectively (P = 0.443 for bleeding rate; P = 0.041 for perforation rate).

Table 1 Comparison of clinicopathological characteristics of differentiated-type early gastric cancer with and without histological heterogeneity

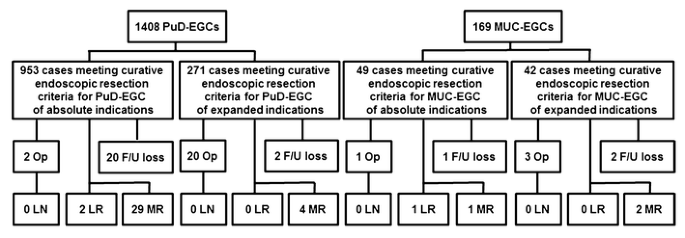

Among 1,408 PuD-EGC treated by ESD, 67.7 % (953/1,408) and 19.2 % (271/1,408) of cases met the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications, respectively. Among 169 MUC-EGC treated by ESD, 29.0 % (49/169) and 24.9 % (42/169) of cases met the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications, respectively (Fig. 2). For PuD-EGC, en bloc resection, R0 resection, and en bloc with R0 resection rates were 98.4 %, 100.0 %, and 98.4 %, respectively, in cases meeting curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute indications, and 97.8 %, 100.0 %, and 97.8 %, respectively, in cases meeting curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of expanded indications. For MUC-EGC, en bloc resection, R0 resection, and en bloc with R0 resection rates were 93.9 %, 100.0 %, and 93.9 %, respectively, in cases meeting curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute indications, and 100.0 %, 100.0 %, and 100.0 %, respectively, in cases meeting curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of expanded indications.

Fig. 2

Flowchart for cases treated by endoscopic submucosal dissections meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications. _PuD_-EGC pure differentiated-type early gastric cancer, MUC-EGC differentiated-type-predominant early gastric cancer mixed with undifferentiated component, Op operation, RM resection margin, F/U follow-up, LN lymph node metastasis, LR local recurrence, MR metachronous recurrence

Clinicopathological features of MUC-EGC according to the proportion of UC

The proportion of UC in MUC-EGC was as follows: 1–9 % in 49 cases, 10–19 % in 61 cases, 20–29 % in 29 cases, 30–39 % in 20 cases, and 40–45 % in 10 cases. Clinicopathological features and endoscopic outcomes of MUC-EGC were compared according to the proportion of UC (<20 % versus ≥20 %). No parameter showed a significant difference according to the proportion of UC in MUC-EGC (Table 2).

Table 2 Comparison of clinicopathological characteristics of differentiated-type early gastric cancer with histological heterogeneity according to the proportion of undifferentiated component

Frequency of LN metastasis in cases undergoing surgical resection after ESD

Figure 2 shows the flowchart for cases treated by ESD meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications. For PuD-EGC, 2 and 20 cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications underwent radical gastrectomy after ESD, and LN metastasis was not observed in any of these cases. In 117 surgically resected cases of PuD-EGC beyond the curative resection criteria, however, LN metastasis was found in 5.1 % (6/117) of cases.

For MUC-EGC, one case meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumor of absolute indication underwent radical gastrectomy after ESD. This case showed poorly differentiated histology in 30 % of the tumor area in the ESD specimen, and the patient requested additional surgical resection for fear of LN metastasis. In addition, three MUC-EGC cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of expanded indications underwent radical gastrectomy after ESD. All these three cases showed minute submucosal invasion of <500 μm in the ESD specimen, and the patients requested additional surgery for fear of LN metastasis. In none of these four MUC-EGC patients who underwent surgical resection was any LN metastasis found in the surgical specimens. In 55 surgically resected cases of MUC-EGC beyond the curative resection criteria, however, LN metastasis was found in 7.3 % (4/55) of cases.

Frequency of local recurrence and LN metastasis during follow-up after ESD

For PuD-EGC, local recurrence after ESD occurred in two cases (0.2 %, 2/931) meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumor of absolute indication. No local recurrence occurred in PuD-EGC cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumor of the expanded indication during the follow-up period after ESD.

For MUC-EGC, local recurrence after ESD occurred in one case (2.1 %, 1/47) meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumor of absolute indication. For the recurred case, the invasion depth of the original tumor was limited to the muscularis mucosa layer, and the tumor size was 2.0 cm. The ESD specimen showed a mixture of signet ring-cell histology accounting for 30 % of the tumor area. This tumor was resected in a piecemeal fashion, and local recurrence occurred 34 months after ESD. The patient underwent surgical resection for locally recurred tumor, and no LN metastasis was found in the surgical specimen. No local recurrence occurred in MUC-EGC cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumor of expanded indication during the follow-up period after ESD.

No LN metastasis or extragastric recurrence occurred during the follow-up period after ESD in either PuD-EGC or MUC-EGC cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indication.

Overall survival after ESD

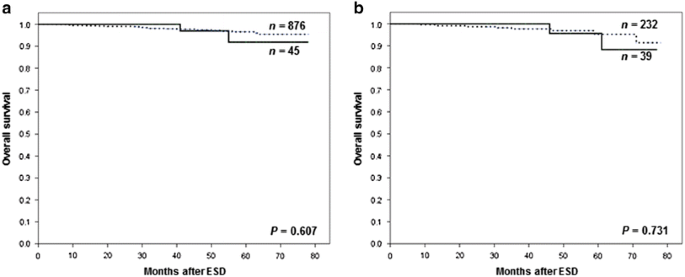

A total of 1,192 patients with single EGC treated by ESD meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indication were included in the overall survival analysis. During a median 48 months of follow-up after ESD (range, 5–78 months), a total of 33 deaths occurred in patients with PuD-EGC and 4 deaths in patients with MUC-EGC. Figure 3 shows Kaplan–Meier overall survival curves for patients with a single EGC meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indication. For cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute indication (Fig. 3a), 3-year overall survival rates were 98.1 % and 100 % and 5-year overall survival rates were 96.6 % and 91.9 % for patients with PuD-EGC and MUC-EGC, respectively. For cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of expanded indication (Fig. 3b), 3-year overall survival rates were 97.7 % and 100 % and 5-year overall survival rates were 95.2 % and 95.7 % for patients with PuD-EGC and MUC-EGC, respectively. In either case, meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indication, there was no statistically significant difference in overall survival between patients with PuD-EGC and MUC-EGC. A total of four patients with MUC-EGC meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indication died during the follow-up period after ESD: one death from lung cancer 55 months after ESD; one death from colon cancer 41 months after ESD; and one death from pneumonia at 46 months and one at 61 months after ESD. These patients’ ages at the time of ESD were 75, 72, 78, and 72 years, respectively. No patient with MUC-EGC meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indication died of recurred gastric cancer during the follow-up period.

Fig. 3

Kaplan–Meier overall survival curves for patients with single early gastric cancer treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). All patients included in the analysis underwent R0 resection. a Cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute indications. b Cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of expanded indications. Dotted line, pure differentiated type early gastric cancer; solid line, differentiated-type-predominant early gastric cancer mixed with undifferentiated component. ESD endoscopic submucosal dissection

Discussion

Currently, ESD is indicated only for EGC with differentiated histology diagnosed from forceps biopsy specimens [1]. However, it is not uncommon to find a mixture of UC with differentiated EGC during histopathological review of ESD specimen including the entire EGC lesion. In this study, MUC-EGC accounted for 10.7 % of all enrolled cases. To date, there have been few studies evaluating the clinicopathological features and prognosis of MUC-EGC despite this considerable prevalence [4–6]. In addition, there has been no large-scale study evaluating the long-term outcomes after ESD for MUC-EGC. Therefore, it remains controversial whether MUC-EGC can be managed in the same way as PuD-EGC and whether ESD has a role in the treatment for MUC-EGC.

Although MUC-EGC showed more aggressive clinicopathological features compared to PuD-EGC (larger tumor size, more frequent submucosal invasion, and lymphovascular invasion), previous studies from surgical series consistently reported the minimal risk of LN metastasis in MUC-EGC cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications, suggesting that ESD might be indicated for these cases [4–6]. Our results supported these previous studies. No LN metastasis or extragastric recurrence occurred during the follow-up period after ESD in MUC-EGC cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications. A total of four MUC-EGC cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications underwent radical gastrectomy after ESD, and no case showed lymph node metastasis. The overall survival of patients with MUC-EGC meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications was comparable to that of PuD-EGC. No patient with MUC-EGC meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications died of recurred gastric cancer during the follow-up period. Given these favorable follow-up results and acceptable en bloc and R0 resection rates for patients with MUC-EGC meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications, ESD might be cautiously indicated for these cases. However, given a case report of the development of LN metastasis 14 months after ESD in patient with MUC-EGC meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of expanded indications [11], further large studies with long-term follow-up are definitely required to establish the detailed indication of ESD for MUC-EGC meeting the expanded indication.

Hanaoka et al. [5] and Takizawa et al. [6] reported that undifferentiated-type-predominant EGC (UC accounting for 51–99 % of total tumor area) showed the highest LN metastasis and lymphatic invasion rate compared to MUC-EGC (UC accounting for <50 % of total tumor area), PuD-EGC, and even pure undifferentiated-type EGC. Hanaoka et al. [5] argued that the highest prevalence of LN metastasis and lymphatic invasion in undifferentiated-type-predominant EGC might be related to the size of the tumor and the horizontal length of the submucosal invasion. These results suggest that the proportion of UC might have impact on the clinicopathological features of MUC-EGC. However, no parameter analyzed in our study showed a significant difference according to the proportion of UC in MUC-EGC.

One interesting finding in our study was that MUC-EGC showed a significantly higher rate of resection margin involvement after ESD compared to PuD-EGC, which could be caused by the presence of UC in MUC-EGC. Kim et al. [12] argued that EGC with poorly differentiated histology had a significantly higher probability of being understaged by endosonographic assessment compared to differentiated-type EGC. Kang et al. [13] reported that lateral and vertical resection margin involvement rates after ESD were 23.3 % and 18.3 % for undifferentiated-type EGC and 8.8 % and 4.8 % for differentiated-type EGC, respectively.

This study had several limitations. First, to a certain extent, there was potential for a selection bias. MUC-EGC with a high proportion of UC could be diagnosed as undifferentiated cancer in a forceps biopsy specimen. Therefore, some patients with MUC-EGC may have undergone surgical resection instead of ESD, especially when the tumor included a high proportion of UC. We tried to minimize the selection bias by including the consecutive patients identified from our prospectively collected database on ESD. Second, there could be an interobserver variation in classifying tumor as MUC-EGC or undifferentiated-type-predominant EGC between two pathologists, especially in cases of UC accounting for 40 % to 60 % of the tumor area. In the present study, however, the majority of MUC-EGC cases (94.1 %, 159/169) had UC less than 40 % of the tumor area. In addition, the majority of undifferentiated-type-predominant EGC cases excluded from the study population showed UC accounting for more than 60 % of the tumor area. In fact, the agreement rate between two pathologists reviewing ESD specimens in this study was 96 % and thus acceptable in classifying tumor as MUC-EGC or undifferentiated-type-predominant EGC. The other limitations were the relatively small number of MUC-EGC cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications. Given these limitations, further large-scale multi-center trials are necessary to confirm our results. However, previous surgical series consistently reported the favorable results showing the minimal risk of LN metastasis in MUC-EGC cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications, which supported our promising follow-up data after ESD for MUC-EGC [4–6].

In conclusion, our results indicated that MUC-EGC had more aggressive clinicopathological features compared to PuD-EGC such as larger tumor size and more frequent submucosal and lymphovascular invasion. Despite these aggressive features, our study showed the favorable long-term follow-up results after ESD if MUC-EGC met the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications. For cases meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications, there was no LN metastasis or extragastric recurrence during follow-up after ESD, and the overall survival rate of MUC-EGC was comparable to that of PuD-EGC. En bloc resection rates of ESD for MUC-EGC were >90 % and thus acceptable. Given these results, ESD may be used as a promising treatment option for MUC-EGCs meeting the curative endoscopic resection criteria for tumors of absolute or expanded indications.

References

- Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:929–42.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–123.

- Kim WH, Park CK, Kim YB, Kim YW, Kim HG, Bae HI, et al. A standardized pathology report for gastric cancer. Korean J Pathol. 2005;39:106–13.

Google Scholar - Mita T, Shimoda T. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis of submucosal invasive differentiated type gastric carcinoma: clinical significance of histological heterogeneity. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:661–8.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hanaoka N, Tanabe S, Mikami T, Okayasu I, Saigenji K. Mixed-histologic-type submucosal invasive gastric cancer as a risk factor for lymph node metastasis: feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2009;41:427–32.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Takizawa K, Ono H, Kakushima N, Tanaka M, Hasuike N, Matsubayashi H, et al. Risk of lymph node metastases from intramucosal gastric cancer in relation to histological types: how to manage the mixed histological type for endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:531–6.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, et al. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219–25.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Lee H, Yun WK, Min BH, Lee JH, Rhee PL, Kim KM, et al. A feasibility study on the expanded indication for endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1985–93.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Min BH, Lee JH, Kim JJ, Shim SG, Chang DK, Kim YH, et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for treating early gastric cancer: comparison with endoscopic mucosal resection after circumferential precutting (EMR-P). Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:201–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Bae SY, Jang TH, Min BH, Lee JH, Rhee PL, Rhee JC, et al. Early additional endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with positive lateral resection margins after initial endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:432–6.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hanaoka N, Tanabe S, Higuchi K, Sasaki T, Nakatani K, Ishido K, et al. A rare case of histologically mixed-type intramucosal gastric cancer accompanied by nodal recurrence and liver metastasis after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:588–90.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kim JH, Song KS, Youn YH, Lee YC, Cheon JH, Song SY, et al. Clinicopathologic factors influence accurate endosonographic assessment for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:901–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kang HY, Kim SG, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for undifferentiated early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:509–16.

Article PubMed Google Scholar