Infectious Diseases in Immigrant Population Related to the Time of Residence in Spain (original) (raw)

Abstract

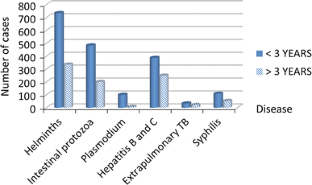

The aim of this study was to evaluate the data on the main imported infectious diseases and public health issues arising from the risk of transmission of tropical and common diseases in the immigrant population. During the period of study, 2,426 immigrants were attended in the Tropical Medicine Unit of the Hospital of Poniente. For each patient, a complete screening for common and tropical diseases was performed. The prevalence and main features of intestinal and urinary parasites, microfilarias, Chagas disease, malaria, hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV) viruses, extrapulmonary tuberculosis and syphilis was investigated taking into account the length of stay in Spain. Sub-Saharan Africa patients who had lived for <3 years in Spain had a high significantly number of infections produced by hookworms, Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma mansoni, Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica/dispar and Plasmodium spp. In patients who had lived for more than 3 years, there were significantly high rates of HBV infections, although HBV rates in sub-Saharan African patients are high even if the patients have been in Spain for <3 years. However, patients with large stays in Spain had also an important number of parasitological diseases. The main objective of the diagnosis is to avoid important public health problems and further complications in patients. It is advisable to carry out a screening of the main transmissible infections in all immigrant population regardless of the time outside their country. This screening should be individualized according to the geographical area of origin.

Access this article

Subscribe and save

- Starting from 10 chapters or articles per month

- Access and download chapters and articles from more than 300k books and 2,500 journals

- Cancel anytime View plans

Buy Now

Price excludes VAT (USA)

Tax calculation will be finalised during checkout.

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Fig. 1

Similar content being viewed by others

References

- Foreigners residents in Spain: main results. Registro Central de la Inmigración. Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social; Septiembre 2013.

- Manzardo C, Treviño B, Gómez i Prat J, et al. Communicable diseases in the immigrant population attended to in a tropical medicine unit: epidemiological aspects and public health issues. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2008;6:4–11.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Ritchie LS. An ether sedimentation technique for routine stool examination. Bull US Army Med Dep. 1948;8:326.

CAS Google Scholar - Knott J. A method for making microfilarial surveys on day blood. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1939;33:191–6.

Article Google Scholar - Sang HT, Petitory J. Techniques de concentration des microfilaires sanguicoles. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1963;56:197–206.

Google Scholar - Praast G, Herzogenrath J, Bernhardt S, et al. Evaluation of the Abbott ARCHITECT Chagas prototype assay. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;69:74–81.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Malan AK, Avelar E, Litwin SE, et al. Serological diagnosis of Trypanosoma cruzi: evaluation of three enzyme immunoassays and an indirect immunofluorescent assay. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:171–8.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Djallé D, Gody JC, Moyen JM, et al. Performance of Paracheck TM-Pf, SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf and SD Bioline malaria Ag-Pf/pan for diagnosis of falciparum malaria in the Central African Republic. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:109.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar - Miedouge M, Legrand-Abravanel F, Lalanne C, et al. Laboratory evaluation of the UniCel DxI 800 analyser (Beckman Coulter) for detecting HBV and HCV serological markers. J Clin Virol. 2009;44:134–7.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - French P, Gomberg M, Janier M, et al. IUSTI: 2008 European guidelines on the management of syphilis. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20:300–9.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Roca C, Balanzó X, Fernández-Roure JL, et al. Enfermedades importadas en inmigrantes africanos: estudio de 1.321 pacientes. Med Clin (Barc). 2002;119:616–9.

Article Google Scholar - Gautret P, Cramer JP, Field V, et al. Infectious diseases among travellers and migrants in Europe, EuroTravNet 2010. Euro Surveill. 2012;17(26):20205.

PubMed Google Scholar - Barret-Connor E. Latent and chronic infections imported from South-east Asia. JAMA. 1978;239:1901–6.

Article Google Scholar - Goldenring JM. Screening immigrant children. West J Med. 1984;140:289.

PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar - Salas SD, Heifetz R, Barrett-Connor E. Intestinal parasites in central American immigrants in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1514–6.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Warren KS, Mahmoud AA, Cummings P, et al. Schistosomiasis mansoni in Yemeni in California: duration of infection, presence of disease, therapeutic management. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1974;23:902–9.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Chabasse D, Bertrand G, Leroux JP, et al. Developmental bilharziasis caused by Schistosoma mansoni discovered 37 years after infestation. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1985;78:643–7.

CAS Google Scholar - Cheever AW. A quantitative post-mortem study of Schistosomiasis mansoni in man. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1968;17:38–64.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Khalaf I, Shokeir A, Shalaby M. Urologic complications of genitourinary schistosomiasis. World J Urol. 2012;30:31–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Schwartz DA. Helminths in the induction of cancer II. Schistosoma haematobium and bladder cancer. Trop Geogr Med. 1981;33:1–7.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kjetland EF, Leutscher PD, Ndhlovu PD. A review of female genital schistosomiasis. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:58–65.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Prendki V, Fenaux P, Durand R, et al. Strongyloidiasis in man 75 years after initial exposure. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:931–2.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:208–17.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Roxby AC, Gottlieb GS, Limaye AP. Strongyloidiasis in transplant patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1411–23.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Carlier Y, Torrico F. Congenital infection with Trypanosoma cruzi: from mechanisms of transmission to strategies for diagnosis and control. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2003;36:767–71.

Article Google Scholar - Schmunis GA. Trypanosoma cruzi, the etiologic agent of Chagas disease: status in the blood supply in endemic and non endemic countries. Transfusion. 1991;31:547–57.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chagas disease after organ transplantation—United States, 2001. MMWR. 2002;51:210–2.

Google Scholar

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Tropical Medicine Unit, Hospital de Poniente, Ctra de Almerimar s/n, 04700, El Ejido, Almería, Spain

Fernando Cobo, Joaquín Salas-Coronas, Mª Teresa Cabezas-Fernández, José Vázquez-Villegas, Mª Isabel Cabeza-Barrera & Manuel J. Soriano-Pérez

Authors

- Fernando Cobo

- Joaquín Salas-Coronas

- Mª Teresa Cabezas-Fernández

- José Vázquez-Villegas

- Mª Isabel Cabeza-Barrera

- Manuel J. Soriano-Pérez

Corresponding author

Correspondence toFernando Cobo.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cobo, F., Salas-Coronas, J., Cabezas-Fernández, M.T. et al. Infectious Diseases in Immigrant Population Related to the Time of Residence in Spain.J Immigrant Minority Health 18, 8–15 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0141-5

- Published: 04 December 2014

- Issue date: February 2016

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0141-5