Noninvasive Assessment of the Severity of Liver Fibrosis in MASLD Patients with Long-Standing Type 2 Diabetes (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), which have a reciprocal relationship compounded by obesity, are highly prevalent in the Middle East affecting morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs.

Objective

This study aimed to assess the severity of MASLD and liver fibrosis among adult Emirati patients with long-standing T2DM.

Design and Participants

This cross-sectional study used noninvasive methods to assess the severity of MASLD and fibrosis progression in an adult cohort of Emirati patients (N = 546) with a mean T2DM duration of 16 years.

Main Measures

Fatty liver infiltration was assessed by hepatic steatosis index (HSI), while fibrosis was assessed by the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index and aspartate aminotransferase/platelet ratio index (APRI). Of those, 108 patients were randomly subjected to ultrasound-based FibroScan® to assess controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) and liver stiffness measurement (LSM).

Key Results

All patients had fatty liver with ~ 83% being categorized as having severe steatosis. Serum-based fibrosis biomarker panels detected significant liver fibrosis in ~ 2.5% of these patients. The APRI appeared to be more restrictive in detecting moderate fibrosis (1.5%) than the FIB-4 index (25.5%). CAP significantly correlated with the LSM, indicating that the two methods contributed to the same underlying pathophysiology. Liver steatosis was more severe in female patients, who were older and had a higher body mass index (BMI) than those with moderate or no significant fibrosis. They also had higher serum liver enzymes and were more likely to have age-related changes in kidney function. Interestingly, severity of both steatosis and fibrosis remained unaffected by age and duration of T2D except for fibrosis severity detected by FibroScan®.

Conclusions

This study highlights the critical need for routine screening of MASLD among Emirati patients with long-standing T2DM, given the high point prevalence of severe steatosis (~ 83%), predominantly among women in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a spectrum of progressive liver disorders characterized by hepatic steatosis on imaging or histology (macro-vesicular steatosis) and the absence of secondary causes of hepatic steatosis, such as significant alcohol consumption, chronic use of medications that cause hepatic steatosis, or hereditary disorders. It is a rapidly growing public health concern affecting approximately one-fourth of the global population, more so among men than women.[1](#ref-CR1 "Puri P, Sanyal AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Definitions, risk factors, and workup. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2012;1(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/cld.81

."),[2](#ref-CR2 "Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Paik JM, Henry A, Van Dongen C, Henry L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology. 2023;77(4).

https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000004

."),[3](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR3 "Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(9).

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00165-0

.")A Delphi consensus by the American Association for Study of Liver Disease, the European Association for Study of the Liver, and the Asociación Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Hígado has now changed the nomenclature of NAFLD to metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD).[4](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR4 "Kanwal F, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Rinella ME. Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease: Update and impact of new nomenclature on the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidance on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. Published online November 9, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000670

."),[5](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR5 "Rinella ME, Lazarus J V., Ratziu V, et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J Hepatol. 2023;79(6).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.06.003

") MASLD is the liver manifestation of metabolic syndrome closely associated with obesity, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and hypertension.[6](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR6 "Lonardo A, Nascimbeni F, Maurantonio M, Marrazzo A, Rinaldi L, Adinolfi LE. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Evolving paradigms. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(36).

https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i36.6571

."),[7](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR7 "Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: Trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(1).

https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2017.109

.") Due to the establishment of a 99% overlap between MASLD- and historical NAFLD-defined populations, findings from NAFLD studies remain valid under the new MASLD definition.[8](#ref-CR8 "Ratziu V, Boursier J, de Ledinghen V, Anty R, Costentin C, Bureau C. Confirmatory biomarker diagnostic studies are not needed when transitioning from NAFLD to MASLD. J Hepatol. 2024;80(2).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.07.017

."),[9](#ref-CR9 "Song SJ, Lai JCT, Wong GLH, Wong VWS, Yip TCF. Can we use old NAFLD data under the new MASLD definition? J Hepatol. 2024;80(2).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.07.021

."),[10](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR10 "Kanwal F, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Rinella ME. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Update and impact of new nomenclature on the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidance on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2024;79(5).

https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000670

.")Despite affecting 25–32% of the pooled global adult population, only a minority of patients with MASLD develop metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), which progresses to significant fibrosis.[3](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR3 "Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00165-0

."),[11](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR11 "Khandelwal R, Dassanayake AS, Conjeevaram HS, Singh SP. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in diabetes: When to refer to the hepatologist? World J Diabetes. 2021;12(9).

https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v12.i9.1479

."),[12](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR12 "Anstee QM, Darlay R, Cockell S, et al. Genome-wide association study of non-alcoholic fatty liver and steatohepatitis in a histologically characterised cohort☆. J Hepatol. 2020;73(3).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.003

.") The progressive nature of MASLD, particularly when associated with advanced fibrosis, needs to be identified in patients at risk (aged > 50 years, with T2D or metabolic syndrome) because of its prognostic implications.[13](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR13 "Marchesini G, Day CP, Dufour JF, et al. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004

.") In an epidemiological cross-sectional study involving 500 participants, 10.2% were diagnosed with MASLD alone and had a greater risk of liver fibrosis and disease progression.[14](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR14 "Ramírez-Mejía MM, Jiménez-Gutiérrez C, Eslam M, George J, Méndez-Sánchez N. Breaking new ground: MASLD vs. MAFLD—which holds the key for risk stratification? Hepatol Int. 2024;18(1).

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-023-10620-y

.") T2DM, a main criterion for MASLD classification, has a reciprocal relationship with MASLD compounded by obesity.[15](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR15 "Aktas G. Serum C-reactive protein to albumin ratio as a reliable marker of diabetic neuropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomol Biomed. 2024 Sep 6;24(5):1380–1386.

https://doi.org/10.17305/bb.2024.10426

.") The complex interrelationship between these conditions is driven by several pathophysiological pathways including insulin resistance,[16](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR16 "Bertot LC, Jeffrey GP, de Boer B, MacQuillan G, Garas G, Chin J, Huang Y, Adams LA. Diabetes impacts prediction of cirrhosis and prognosis by non-invasive fibrosis models in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2018;38(10):1793-1802.

https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13739

.") inflammation,[17](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR17 "Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1793-801.

https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI29069

.") and lipotoxicity.[18](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR18 "Barrera F, Uribe J, Olvares N, Huerta P, Cabrera D, Romero-Gómez M. The Janus of a disease: Diabetes and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2024;29(4).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aohep.2024.101501

."),[19](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR19 "Zheng H, Sechi LA, Navarese EP, Casu G, Vidili G. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and cardiovascular risk: a comprehensive review. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02434-5

.") T2DM is both a consequence and a contributor to MASLD as hyperglycemia exacerbates liver inflammation and fibrosis. Chronic inflammation also plays a central role in the pathogenesis of MASLD, with pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress further damaging liver cells.[17](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR17 "Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1793-801.

https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI29069

."),[19](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR19 "Zheng H, Sechi LA, Navarese EP, Casu G, Vidili G. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and cardiovascular risk: a comprehensive review. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02434-5

.") Excess adipose tissue in obesity contributes to insulin resistance which in turn, promotes hepatic fat accumulation and inflammation, leading to MASLD.[19](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR19 "Zheng H, Sechi LA, Navarese EP, Casu G, Vidili G. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and cardiovascular risk: a comprehensive review. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02434-5

.") This interplay underscored the importance of addressing the association of T2DM and MASLD in our studies.T2DM has a significant impact on morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs.[20](#ref-CR20 "Park SK, Seo MH, Shin HC, Ryoo JH. Clinical availability of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as an early predictor of type 2 diabetes mellitus in korean men: 5-year prospective cohort study. Hepatology. 2013;57(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26183

."),[21](#ref-CR21 "Anstee QM, Targher G, Day CP. Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(6).

https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2013.41

."),[22](#ref-CR22 "Björkström K, Stål P, Hultcrantz R, Hagström H. Histologic Scores for Fat and Fibrosis Associate With Development of Type 2 Diabetes in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(9).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.04.040

."),[23](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR23 "Mantovani A, Byrne CD, Bonora E, Targher G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(2).

https://doi.org/10.2337/dc17-1902

.") It affects 55.5% of the global population with MASLD and 37.3% with MASH.[24](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR24 "Younossi ZM, Golabi P, de Avila L, et al. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2019;71(4).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.021

.") Certain ethnic groups, particularly those of Asian and Middle Eastern origin, are considered at risk mainly because of changing lifestyles, dietary habits, and cardiovascular morbidity and may result in a major healthcare burden, mainly in Southeast Asia, North Africa, the Middle East, and southern sub-Saharan Africa.[25](#ref-CR25 "Rhee EJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes: An epidemiological perspective. Endocrinol Metab. 2019;34(3).

https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2019.34.3.226

."),[26](#ref-CR26 "Stevens GA, Singh GM, Lu Y, et al. * for the Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group (Body Mass Index). Popul Health Metr. 2012;10.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7954-10-22

."),[27](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR27 "Wang D, Xu Y, Zhu Z, et al. Changes in the global, regional, and national burdens of NAFLD from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. Front Nutr. 2022;9.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.1047129

.") A meta-analysis of adult patients with MASLD reported a higher prevalence in the Middle East region (31.79%) than in other regions.[2](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR2 "Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Paik JM, Henry A, Van Dongen C, Henry L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology. 2023;77(4).

https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000004

.") As of 2017, approximately 25% of the estimated Emirati population of the UAE was diagnosed with MASLD, and the prevalence of MASLD is projected to double in the next decade.[28](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR28 "Alswat K, Aljumah AA, Sanai FM, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease burden-Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates, 2017–2030. Saudi J Gastroentero. 2018;24(4).

https://doi.org/10.4103/sjg.SJG_122_18

.")The clinical and economic limitations of liver biopsy, the “gold standard” for diagnosing liver disease, have prompted the establishment of noninvasive tests (NITs), such as serum biomarkers, scoring systems, and imaging tests, to differentiate steatohepatitis from simple steatosis and to identify fibrosis, as it is the critical determinant of progression/regression, prognosis, and treatment decisions.[29](#ref-CR29 "Wilson S, Chalasani N. Noninvasive Markers of Advanced Histology in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Are We There yet? Gastroenterology. 2007;133(4). https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.045

."),[30](#ref-CR30 "Yoneda M, Imajo K, Takahashi H, et al. Clinical strategy of diagnosing and following patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease based on invasive and noninvasive methods. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(2).

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-017-1414-2

."),[31](#ref-CR31 "Juo YY, Livingston EH. Testing for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2019;322(18).

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.10696

."),[32](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR32 "Singh SP, Barik RK. NonInvasive Biomarkers in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Are We There Yet? J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2020;10(1).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2019.09.006

.") Recent data suggest that the results from biomarker validation studies among patients with NAFLD can be applied to patients with MASLD.[11](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR11 "Khandelwal R, Dassanayake AS, Conjeevaram HS, Singh SP. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in diabetes: When to refer to the hepatologist? World J Diabetes. 2021;12(9).

https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v12.i9.1479

."),[33](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR33 "Hagström H, Vessby J, Ekstedt M, Shang Y. 99% of patients with NAFLD meet MASLD criteria and natural history is therefore identical. J Hepatol. 2024;80(2).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.08.026

.") Lee et al.[34](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR34 "Lee JH, Kim D, Kim HJ, et al. Hepatic steatosis index: A simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42(7).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.002

.") showed that the hepatic steatosis index (HSI), which uses liver enzyme levels and BMI for the detection of MASLD, is significantly correlated with hepatic steatosis grades determined by ultrasonography. The blood-based fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index and AST:platelet ratio index (APRI) have also been proven to be reliable methods for detecting advanced fibrosis among MASLD patients with FIB-4 showing the best sensitivity and APRI showing the best specificity in predicting advanced stages of liver fibrosis among MASLD patients.[35](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR35 "Amernia B, Moosavy SH, Banookh F, Zoghi G. FIB-4, APRI, and AST/ALT ratio compared to FibroScan for the assessment of hepatic fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Bandar Abbas, Iran. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21(1).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-02038-3

.")Ultrasound-based vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE™: FibroScan®) is the most used noninvasive method for assessing liver stiffness and can be used to exclude significant hepatic fibrosis. A widely followed approach harnesses the potential of serum-based biomarkers and scoring systems in conjunction with liver stiffness measurement (LSM) by VCTE™ to assess the stage of fibrosis and portal hypertension in patients with chronic liver disease of different etiologies.[30](#ref-CR30 "Yoneda M, Imajo K, Takahashi H, et al. Clinical strategy of diagnosing and following patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease based on invasive and noninvasive methods. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-017-1414-2

."),[31](#ref-CR31 "Juo YY, Livingston EH. Testing for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2019;322(18).

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.10696

."),[32](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR32 "Singh SP, Barik RK. NonInvasive Biomarkers in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Are We There Yet? J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2020;10(1).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2019.09.006

."),[36](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR36 "Friedrich-Rust M, Ong MF, Martens S, et al. Performance of Transient Elastography for the Staging of Liver Fibrosis: A Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(4).

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.034

.") The new Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD)[37](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR37 "Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Siddiqui MS, et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77(5).

https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000323

.") suggests the use of VCTE™ for detecting and diagnosing MASLD in high-risk individuals, including those with T2DM. It also suggests the use of the controlled attenuation parameter (CAP)™ (FibroScan®) as a point-of-care technique to identify steatosis, and if the FIB-4 index is ≥ 1.3, VCTE™ may be used to exclude advanced fibrosis.According to the current consensus of the American Diabetic Association (ADA), in the absence of alcohol intake, patients with T2DM with either elevated liver enzymes or fatty liver on ultrasound imaging should be screened for steatohepatitis or fibrosis.[38](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR38 "Ng CH, Chan KE, Chin YH, et al. The effect of diabetes and prediabetes on the prevalence, complications and mortality in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28(3). https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2022.0096

.") Earlier, a meta-analysis by Younossi et al.[24](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR24 "Younossi ZM, Golabi P, de Avila L, et al. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2019;71(4).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.021

.") reported a regional prevalence of 67.29% for MASLD among patients with T2DM in West Asia (Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia). Given the rapid increase in T2DM incidence in the Emirati population of the UAE[39](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR39 "Kalan Farmanfarma KH, Ansari-Moghaddam A, Zareban I, Adineh HA. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Middle–East: Systematic review& meta-analysis. Prim Care Diabetes. 2020;14(4).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2020.01.003

.") and the resulting complex web of metabolic disturbances, it is crucial to screen for MASLD and associated complications in this population. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to evaluate the severity of MASLD and liver fibrosis among Emirati patients with long-standing T2DM.MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Dubai Diabetes Center (DDC) and Dubai Hospital (DH), both of which follow the American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care for Diabetes.[40](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR40 "Feldman H, ElSayed NA, McCoy RG, et al. Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin Diabetes. 2023;41(1). https://doi.org/10.2337/cd23-as01

.") Ethical approval was obtained from the Dubai Scientific Research Ethics Committee (DSREC) and the Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine & Health Sciences’ Institutional Review Board (MBRU-IRB). All participating patients were provided with detailed explanations of the study, reasons, and implications prior to obtaining written informed consent.Patients

A total of 623 Emirati patients who visited the DDC and DH between 2019 and 2022 were primarily screened for T2DM according to the following inclusion/exclusion criteria:

- Patients aged > 18 years who provided written informed consent were included. Those who were not willing or unable to provide informed consent were excluded.

- Patients were diagnosed with T2DM with or without complications by a registered healthcare practitioner according to the “SALAMA,” an Electronic Dubai Health Information System.

- Patients must have a negative glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody (GADA) test.

- Patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (GADA test is positive), suspected maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY), or chronic diseases such as malignancy, blood diseases, or recent chemotherapy were excluded.

Data Collection

Clinical data of the study participants were obtained by a healthcare practitioner through structured face-to-face questionnaires and supplemented by demographic information, medical history, lifestyle habits, and anthropometric measurements downloaded from the electronic SALAMA Health Information System, adhering to Dubai Health regulations and guidelines and conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013). The anonymized data included laboratory data comprising liver function tests, lipid profiles, fasting glucose levels, and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels.

Of the 623 T2D Emirati patients, 546 had complete data and satisfied the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The 546 patients were screened for steatosis by the HSI[34](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR34 "Lee JH, Kim D, Kim HJ, et al. Hepatic steatosis index: A simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.002

.") and fibrosis severity using the well-validated serum biomarker scoring systems FIB-4 index[41](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR41 "Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43(6).

https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.21178

.") and APRI[42](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR42 "Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38(2).

https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2003.50346

.") with the following formulae:- (1)

HSI = 8 × (ALT/AST ratio) + BMI + 2 (if female) + 2 (if diabetes mellitus) - (2)

APRI = (AST/ULN of AST = 40)/(PLT/ULN of PLT = 450,000) - (3)

FIB-4 = (age × AST)/(PLT × sqrt (ALT))

where AST is aspartate aminotransferase in U/L, ALT is alanine aminotransferase in U/L, BMI is body mass index in kilograms per square meter, ULN of AST is the upper limit of normal for AST, PLT is the platelet count in 109/L, ULN of PLT is the upper limit of normal for platelet count, and age is in years. The severity was scaled according to the cut-offs shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1 Cutoffs for the Categorization of Liver Steatosis Grades by Noninvasive Techniques

Table 2 Cutoffs for the Categorization of Liver Fibrosis Severity by Noninvasive Techniques

Upon receiving the informed consent, 108 patients from the study cohort, with similar clinical and laboratory parameters, were randomly selected on the basis of FIB-4 index (17% of low risk, 25% of uncertain, and 43% of high risk) and examined for LSMs expressed in kilopascals (kPa) by liver elastography (FibroScan® compact 530; Echosens, Paris, France) and related to fibrosis severity. Simultaneously, the CAP™ score, a measure of fat accumulation in the liver expressed as decibels per meter (dB/m), was also determined from FibroScan®. Imaging was performed at the DDC between December 2022 and March 2023 by a trained FibroScan® operator. Elastography was performed twice to obtain an average of two readings and reduce test bias. Table 1 and Table 2 show the cutoff values applied for determining steatosis and fibrosis risk, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical data analysis was performed using IBM-SPSS for Windows version 28.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Categorical variables were described by using proportions, and continuous variables were described by a measure of tendency and a measure of dispersion. Categorical variables were cross-tabulated to examine the independence between variables; for such variables, the chi-square (_χ_2) test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, was used. The Kolmogorov‒Smirnov test was used to test the normality of continuous variables. The Mann‒Whitney test was used to compare the means between two groups. Continuous variables are shown as medians (25th percentile, 75th percentile) and were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test. To measure the linear and nonlinear relationships between two variables when the data were not normally distributed, the nonparametric Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) was used. The diagnostic performance (positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), sensitivity, and specificity) of serum-based markers against liver elastography methods for liver steatosis and fibrosis was categorically determined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance in all analyses.

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics of the Study Cohort

A total of 546 patients satisfied the inclusion–exclusion criteria of the study, with the majority being women (N = 311, 56.9%). The patients in the study cohort (N = 546) were all diagnosed with T2DM by registered medical practitioners in Dubai, with a mean duration of diabetes of 15.45 (± 8) years. The mean age at diagnosis was 42 (± 10) years, the mean fasting blood glucose level was 144 (± 51) mg/dL, the mean AST:ALT ratio was 1.09, the mean HbA1c level was 7.6 (± 1.6%), and the mean C-Reactive Protein was 17.1 mg/L (± 17.4 SD) (< 5 mg/L). No significant sex difference was observed (Table S1). The cohort included 0.7% underweight (_N_ = 4), 11.1% normal (_N_ = 61), 59.8% overweight (_N_ = 180), and 55.1% obese (_N_ = 301) participants. A total of 30% (_N_ = 169) had elevated triglycerides, 5% (_N_ = 29) had elevated AST, and 12% (_N_ = 66) had elevated ALT. High waist circumference (WC) was reported in 60% of men (WC > 40 inches, N = 141/235) and 84% of women (WC > 35 inches, N = 262/311). Similarly, 62% of the patients had an HbA1c > 7% (Table S2).

Hepatic Steatosis Severity Among Emirati Patients with MASLD

On screening for hepatic steatosis using serum HSI, 83% of the patients had significantly severe steatosis, and 15.4% had moderate steatosis (Table 3). There were no significant differences in age at diagnosis of T2DM or duration of diabetes among the three categories of steatosis. However, liver steatosis increased significantly (P < 0.001) with increasing BMI. Approximately 55% of the cohort were obese with severe steatosis (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 3 Demographics of 546 T2DM Emirati Patients Categorized Based on Steatosis Severity

Hepatic Fibrosis Severity Among Emirati Patients with MASLD

Assessment of liver fibrosis in the 546 T2DM Emirati patients by blood-based markers revealed a significantly lower number of patients with moderate/severe fibrosis according to the APRI than according to the FIB-4 index (Tables 4 and 5). While the APRI identified 96% of the patients with mild fibrosis, the FIB-4 index identified only 72%. Although 83% of the cohort exhibited severe steatosis, both the FIB-4 index and APRI identified severe fibrosis in only 2.5% of patients. Demographic characteristics such as sex, age, age at diagnosis of T2DM, and duration of T2DM were not significantly correlated with the severity of fibrosis according to either index. However, liver fibrosis, such as steatosis, seems to increase significantly (P < 0.001) with increasing BMI. Pearson’s chi-square was used to compare the distribution of steatosis by FIB-4 and APRI. The chi-square statistic obtained was highly significant (135.7589 and df = 2) (P value is < 0.00001). The main difference was in the distribution of mild and moderate cases between FIB-4 and APRI. The sensitivity of FIB-4 was 88% while that of APRI was 12%. On the other hand, the specificity of FIB-4 was 72% while that of APRI was 96%. However, both methods gave the same estimate for the severe form.

Table 4 Demographics of 546 T2D Emirati Patients Categorized According to Liver Fibrosis Severity based on the FIB-4 Index

Table 5 Demographics of 546 T2D Patients Categorized According to Fibrosis Severity based on APRI

Correlations Between Serum-Based Noninvasive Tests and Imaging-Based Transient Elastography (TE)

A total of 108 T2DM Emirati patients were randomly selected for TE by FibroScan®. The sub-cohort demographics are shown in Table S3. The mean age at diagnosis in the sub-cohort was ~ 41 years, the mean BMI was 30.71 kg/m2, the mean fasting blood glucose level was 147.1 (± 45) mg/dL, the mean AST:ALT ratio was 1.29, the mean HbA1c level was 7.3 (± 1.4%), and the mean C-reactive protein was 19.9 mg/L (± 37.3 SD) (< 5 mg/L). No significant sex differences were observed (Table S3). The demographic distribution for steatosis and fibrosis severity determined by FibroScan® for the sub-cohort of 108 T2DM Emirati patients is shown in Table 6. Although the prevalence of moderate/severe steatosis was 69%, only 22% of patients displayed moderate/severe fibrosis. Only age of diagnosis of T2DM and BMI differed significantly between the groups (_P_ > 0.05). Other parameters showed no difference. However, patients with mild steatosis were overweight, while patients with moderate/severe steatosis were significantly more likely to be obese (P value < 0.001). Nearly 51% of the sub-cohorts were obese, 29% had elevated triglycerides, 9.3% had elevated AST, and 11.2% had elevated ALT. Cardiometabolic risk factors such as high WC were reported in 59% of men (WC > 40 inches, N = 30/57) and 86% of women (Table S4).

Table 6 Demographics of 108 T2DM Emirati Patients with MASLD Categorized According to Severity Determined by Imaging-Based Transient Elastography (TE)

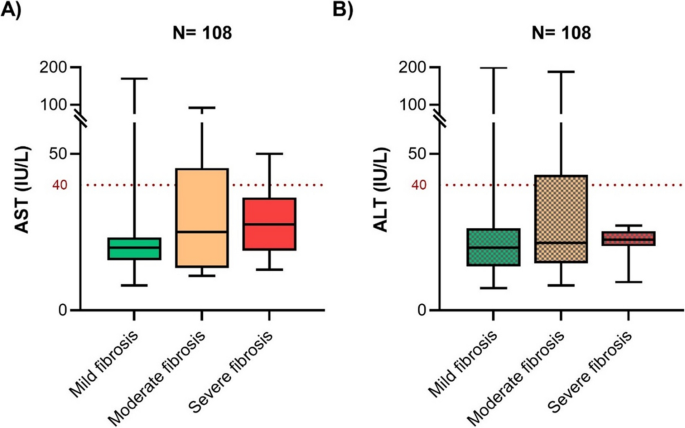

The liver stiffness measurements of the 108 patients in the T2DM sub-cohort showed that 12 had moderate fibrosis, and only 10 had severe fibrosis. Patients with severe fibrosis were diagnosed with diabetes at an older age than those with mild/moderate fibrosis. Although the ALT level was greater than the AST level in the total cohort, no significant difference was observed in the sub-cohort (Supplementary Fig. 2). Of the 9.3% of patients with elevated AST, 5% had severe fibrosis (according to the LSM), and of the 11.2% of patients with elevated ALT, 8% had severe fibrosis (Fig. 1). No significant differences in the AST/ALT ratio were found between the fibrosis categories.

Figure 1

The AST and ALT profiles of the study cohorts. Box plots depicting the variations in A AST and B ALT across fibrosis severities determined by LSM in the sub-cohort are also depicted as box plots. The Kruskal‒Wallis test showed no significant difference between the severity groups. The dotted horizontal line (red) is the cutoff for elevated AST and ALT levels. For each box plot, the solid lines represent the median, boxes represent the lower and upper quartiles, and whiskers represent the minimum and maximum values.

To assess the relationship between serum biomarkers (FIB-4 and APRI) and imaging-based LSM, the Spearman correlation test was performed (Table 7). The FIB-4 index and APRI showed the greatest correlation between methods (ρ = 0.814, P value < 0.001). Weakly significant positive correlations were also found between the FIB-4 index and LSM (ρ = 0.231, P = 0.016), between the APRI and LSM (ρ = 0.206, P = 0.032), and between the LSM and CAP (ρ = 0.262, P = 0.006). No significant correlation was detected between the HSI and CAP scores.

Table 7 Correlations Between Serum-Based NITs of MASLD and Transient Elastography for the Sub-cohort of 108 Patients

The diagnostic accuracy of the blood-based markers against the TE for both steatosis and fibrosis showed that more positive cases were detected by blood-based tests than without the test, with a very low rate of false positives (Table S5).

DISCUSSION

In this study, a cohort of 546 Emirati patients with long-standing T2D were screened for liver steatosis using HSI[34](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR34 "Lee JH, Kim D, Kim HJ, et al. Hepatic steatosis index: A simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.002

.") and for liver fibrosis using the FIB-4 index[41](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR41 "Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43(6).

https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.21178

.") and APRI indices.[34](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR34 "Lee JH, Kim D, Kim HJ, et al. Hepatic steatosis index: A simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42(7).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.002

.") Approximately 98% of patients showed moderate-to-severe steatosis, which increased proportionately with increasing BMI. Using FIB-4, 20% of patients had moderate-to-severe liver fibrosis, which proportionately increased with increasing BMI. Both the APRI and FIB-4 indices consistently identified patients with severe fibrosis at the \~ 2.5% level. Sex differences were detected for steatosis but not for fibrosis, with more women diagnosed with fatty liver than men. A further sub-cohort of 108/546 patients underwent transient elastography. Using CAP scores, 18% had moderate steatosis, and 51% had severe steatosis. Using LSM, 11% of patients had moderate fibrosis, while 9% had severe fibrosis. Although 51% of the 108 sub-cohort displayed severe steatosis, only 9% had severe liver fibrosis.The diagnostic technique used in any study significantly impacts the incidence of steatosis in patients with T2DM. This study reported a prevalence of 70% by transient elastography, similar to the findings of Lomonaco et al.[45](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR45 "Lomonaco R, Leiva EG, Bril F, et al. Advanced liver fibrosis is common in patients with type 2 diabetes followed in the outpatient setting: The need for systematic screening. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):399-406. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-1997

.") which is higher than that reported by Younossi et al.[24](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR24 "Younossi ZM, Golabi P, de Avila L, et al. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2019;71(4).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.021

.") based on ultrasound (\~ 55%). Moderate-to-advanced fibrosis (F2 or higher), an established risk factor for cirrhosis and overall mortality, affects at least one out of six patients with T2DM. These results support the use of the American Diabetes Association guidelines to screen for clinically significant fibrosis in patients with T2DM with steatosis or elevated ALT.A significantly high number of patients in our study were identified to have severe fibrosis by FibroScan® (~ 9%). Lomonaco et al.[45](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR45 "Lomonaco R, Leiva EG, Bril F, et al. Advanced liver fibrosis is common in patients with type 2 diabetes followed in the outpatient setting: The need for systematic screening. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):399-406. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-1997

.") reported similar results in a study involving 561 T2DM patients in the USA. In the present study, imaging-based measurements of steatosis severity (CAP) were significantly correlated with measurements of fibrosis severity (LSM), as reported by Shah et al.[46](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR46 "Shah AG, Lydecker A, Murray K, et al. Comparison of noninvasive markers of fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(10):1104-1112.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.033

.") These findings indicate that the two contribute to the same underlying pathophysiology. The LSM measured by elastography was significantly correlated with the FIB-4 index and APRI. In general, patients with MASLD in this study had higher BMIs, hyperlipidemia, and kidney dysfunction. Patients with moderate/severe fibrosis were older, had a higher BMI, and were diagnosed with T2DM at an older age than those with mild or no fibrosis. The risk of developing MASH increases with increasing BMI.[47](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR47 "Alqahtani SA, Golabi P, Paik JM, et al. Performance of Noninvasive Liver Fibrosis Tests in Morbidly Obese Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Obes Surg. 2021;31(5).

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04996-1

.") The positive correlation of BMI with disease severity shows that the Emirati population, which is adversely affected by obesity, is at high risk of developing chronic liver disease. However, it seems that the control of glucose homeostasis in patients with long-term T2DM, such as fasting blood glucose and HbA1c levels, is no longer related to the severity of MASLD. Elevated AST or ALT (≥ 40 units/L) was present in a minority of patients with steatosis (8% and 13%, respectively) or with liver fibrosis (18% and 28%, respectively). This suggests that the AST/ALT ratio alone is insufficient for initial screening. However, performance may be enhanced by imaging (e.g., transient elastography) and plasma diagnostic panels (e.g., FIB-4 and APRI).NITs for liver fibrosis staging are a major benefit to patients with MASLD. Given its high prevalence, which affects millions of people worldwide, the invasiveness of liver biopsy and sampling errors make it impractical, especially for the periodic assessment required for monitoring disease progression.[48](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR48 "Arab JP, Barrera F, Arrese M. The evolving role of liver biopsy in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2018;17(6). https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0012.7188

.") NITs allow rapid assessment of large numbers of patients and reliably exclude advanced fibrosis in a high proportion of patients with MASLD (52–62%), allowing liver biopsy to be used in a more direct manner.[49](#ref-CR49 "McPherson S, Stewart SF, Henderson E, Burt AD, Day CP. Simple non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can reliably exclude advanced fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2010;59(9).

https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.216077

."),[50](#ref-CR50 "Chou R, Wasson N. Blood tests to diagnose fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(11).

https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00005

."),[51](#ref-CR51 "Xiao G, Zhu S, Xiao X, Yan L, Yang J, Wu G. Comparison of laboratory tests, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance elastography to detect fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;66(5).

https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29302

."),[52](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR52 "Castera L, Friedrich-Rust M, Loomba R. Noninvasive Assessment of Liver Disease in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(5).

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.036

.") In many clinics, blood-based markers are the most practical tests widely used. However, most experts consider transient elastography to be the most accurate NIT for identifying Metavir fibrosis of stage > F3, but in clinical practice, it is typically used in conjunction with other indirect or direct measures of hepatic fibrosis.[53](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR53 "Petta S, Wong VWS, Cammà C, et al. Serial combination of non-invasive tools improves the diagnostic accuracy of severe liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(6).

https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14219

.") These factors offer quick and economic benefits to patients with MASLD and the healthcare system, thereby allowing periodic monitoring of disease progression, especially in populations with a high prevalence of risk factors such as obesity and T2DM. Insulin resistance, a key pathophysiological feature of T2DM, plays a central role in the development and progression of MASLD by promoting hepatic lipid accumulation.[54](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR54 "Targher G, Corey KE, Byrne CD, Roden M. The complex link between NAFLD and type 2 diabetes mellitus — mechanisms and treatments. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(9).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-021-00448-y

.") Among blood-based tests, the AUROC-measured accuracy of the FIB-4 index is significantly better for diagnosing advanced fibrosis.[47](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR47 "Alqahtani SA, Golabi P, Paik JM, et al. Performance of Noninvasive Liver Fibrosis Tests in Morbidly Obese Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Obes Surg. 2021;31(5).

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04996-1

."),[55](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR55 "Joo SK, Kim W, Kim D, et al. Steatosis severity affects the diagnostic performances of noninvasive fibrosis tests in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver International. 2018;38(2).

https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13549

."),[56](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR56 "Durazzo M, Marzari L, BoNetto S, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Diagnostic accuracy of different scores. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2021;66(4).

https://doi.org/10.23736/S1121-421X.20.02753-1

.") However, this can be affected by the prevalence of obesity among MASLD patients.[55](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR55 "Joo SK, Kim W, Kim D, et al. Steatosis severity affects the diagnostic performances of noninvasive fibrosis tests in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver International. 2018;38(2).

https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13549

.") Steatosis affects the sensitivity of the FIB-4 index without affecting its specificity in patients with MASLD syndrome.[55](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR55 "Joo SK, Kim W, Kim D, et al. Steatosis severity affects the diagnostic performances of noninvasive fibrosis tests in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver International. 2018;38(2).

https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13549

.") Similar results have been obtained for LSM in the presence of severe steatosis among patients with advanced fibrosis.[57](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR57 "Petta S, Maida M, Macaluso FS, et al. The Severity of Steatosis Influences Liver Stiffness Measurement in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Published online 2015.

https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27844/suppinfo

.")The use of noninvasive fibrosis scoring systems was validated by Önnerhag et al.[58](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR58 "Önnerhag K, Hartman H, Nilsson PM, Lindgren S. Non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can predict future metabolic complications and overall mortality in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2019.1583366

.") in a study with a long-term follow-up time (\~ 19 years on average). They also confirmed a significant correlation between the scores and incident DM and cardiovascular disease. The International Clinical Practice Guidelines[43](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR43 "Cusi K, Isaacs S, Barb D, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Primary Care and Endocrinology Clinical Settings: Co-Sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD). Endocr Pract. 2022;28(5):528-562.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eprac.2022.03.010

.") recommend screening for MASLD to be part of routine work-up in patients with type 2 diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome. The EASL guidelines[16](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR16 "Bertot LC, Jeffrey GP, de Boer B, MacQuillan G, Garas G, Chin J, Huang Y, Adams LA. Diabetes impacts prediction of cirrhosis and prognosis by non-invasive fibrosis models in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2018;38(10):1793-1802.

https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13739

.") for MASLD management endorse the APRI, FIB-4, and LSM as the most validated tools for the diagnosis of severe fibrosis without a consensus on thresholds or strategies for their application in clinical practice when trying to avoid liver biopsy. Calculating the FIB-4 index and APRI at regular intervals, not only at baseline, will likely increase the predictive capacity. However, this finding indicates the possibility for early assessment of MASLD patients at risk of future complications.[58](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR58 "Önnerhag K, Hartman H, Nilsson PM, Lindgren S. Non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can predict future metabolic complications and overall mortality in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(3).

https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2019.1583366

.")As of 2024, an average of 32.1% of the adult population of the UAE (men, 28.6%; women, 39.4%) is obese, with 91.3% being overweight (men, 71.8%; women, 69.7%) and at risk of obesity.[59](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR59 "Phelps NH, Singleton RK, Zhou B, et al. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2024;403(10431). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02750-2

.") In other Middle East and North Africa countries, the age-standardized prevalence of obesity in adults increased from 1990 to 2022 for both sexes.[59](/article/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2#ref-CR59 "Phelps NH, Singleton RK, Zhou B, et al. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2024;403(10431).

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02750-2

.") With similar risk factors, a wider screening of associated metabolic diseases such as T2DM, obesity, and MASLD among these countries of similar ethnic origin is warranted.Conclusions

This is the first large-scale study of MASLD in the UAE aiming to establish the magnitude of disease burden in random patients with long-term T2DM with the aim of improving noninvasive diagnosis and future management strategies. The concomitant use of imaging (TE) and a blood biomarker panel approach reduces the misdiagnosis of severe fibrosis. The alarming rate of steatosis (≥ F2 > 70%) among Emirati diabetes patients indicates a high risk of severe liver fibrosis in the population. The current study identified one in four participants (20%) with moderate-to-severe fibrosis by transient elastography, which was similar to the results of the blood-based FIB-4 index (≥ F2, 28%) but greater than the APRI (≥ F2, 4).

Limitations

Several confounding factors may affect the results, such as the accuracy of laboratory parameters, false elevations in LSMs due to acute hepatitis, extrahepatic cholestasis, congestive heart failure, hepatic amyloidosis, and recent food intake. The current study was a one-time study conducted in one clinical center, and the results need to be validated in prospective studies with larger numbers of Emirati T2D patients from all over the UAE with follow-ups.

Data Availability:

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information.

Abbreviations

NAFLD:

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

MASLD:

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease

T2DM:

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

FIB-4:

Fibrosis-4

APRI:

Aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index

HSI:

Hepatic steatosis index

LSM:

Liver stiffness measurement

CAP:

Controlled attenuation parameter

NASH:

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

NIT:

Noninvasive tests

VCTE:

Vibration-controlled transient elastography

ADA:

American Diabetic Association

GADA:

Glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies

MODY:

Maturity-onset diabetes of the young

HbA1c:

Hemoglobin A1c

BMI:

Body mass index

AST:

Aspartate aminotransferase

ALT:

Alanine aminotransferase

kPa:

Kilopascals

dB/m:

Decibels per meter

CI:

Confidence interval

SD:

Standard deviation

ρ :

Rho

χ 2 :

Chi-square

DDC:

Dubai Diabetes Center

DSREC:

Dubai Scientific Research Ethics Committee

IRB:

Institutional review board

PPV:

Positive predictive value

NPV:

Negative predictive value

ROC:

Receiver operating characteristic

References

- Puri P, Sanyal AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Definitions, risk factors, and workup. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2012;1(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/cld.81.

- Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Paik JM, Henry A, Van Dongen C, Henry L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology. 2023;77(4). https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000004.

- Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00165-0.

- Kanwal F, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Rinella ME. Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease: Update and impact of new nomenclature on the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidance on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. Published online November 9, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000670.

- Rinella ME, Lazarus J V., Ratziu V, et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J Hepatol. 2023;79(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.06.003

- Lonardo A, Nascimbeni F, Maurantonio M, Marrazzo A, Rinaldi L, Adinolfi LE. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Evolving paradigms. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(36). https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i36.6571.

- Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: Trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2017.109.

- Ratziu V, Boursier J, de Ledinghen V, Anty R, Costentin C, Bureau C. Confirmatory biomarker diagnostic studies are not needed when transitioning from NAFLD to MASLD. J Hepatol. 2024;80(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.07.017.

- Song SJ, Lai JCT, Wong GLH, Wong VWS, Yip TCF. Can we use old NAFLD data under the new MASLD definition? J Hepatol. 2024;80(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.07.021.

- Kanwal F, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Rinella ME. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Update and impact of new nomenclature on the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidance on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2024;79(5). https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000670.

- Khandelwal R, Dassanayake AS, Conjeevaram HS, Singh SP. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in diabetes: When to refer to the hepatologist? World J Diabetes. 2021;12(9). https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v12.i9.1479.

- Anstee QM, Darlay R, Cockell S, et al. Genome-wide association study of non-alcoholic fatty liver and steatohepatitis in a histologically characterised cohort☆. J Hepatol. 2020;73(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.003.

- Marchesini G, Day CP, Dufour JF, et al. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004.

- Ramírez-Mejía MM, Jiménez-Gutiérrez C, Eslam M, George J, Méndez-Sánchez N. Breaking new ground: MASLD vs. MAFLD—which holds the key for risk stratification? Hepatol Int. 2024;18(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-023-10620-y.

- Aktas G. Serum C-reactive protein to albumin ratio as a reliable marker of diabetic neuropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomol Biomed. 2024 Sep 6;24(5):1380–1386. https://doi.org/10.17305/bb.2024.10426.

- Bertot LC, Jeffrey GP, de Boer B, MacQuillan G, Garas G, Chin J, Huang Y, Adams LA. Diabetes impacts prediction of cirrhosis and prognosis by non-invasive fibrosis models in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2018;38(10):1793-1802. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13739.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1793-801. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI29069.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Barrera F, Uribe J, Olvares N, Huerta P, Cabrera D, Romero-Gómez M. The Janus of a disease: Diabetes and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2024;29(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aohep.2024.101501.

- Zheng H, Sechi LA, Navarese EP, Casu G, Vidili G. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and cardiovascular risk: a comprehensive review. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02434-5.

- Park SK, Seo MH, Shin HC, Ryoo JH. Clinical availability of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as an early predictor of type 2 diabetes mellitus in korean men: 5-year prospective cohort study. Hepatology. 2013;57(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26183.

- Anstee QM, Targher G, Day CP. Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(6). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2013.41.

- Björkström K, Stål P, Hultcrantz R, Hagström H. Histologic Scores for Fat and Fibrosis Associate With Development of Type 2 Diabetes in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.04.040.

- Mantovani A, Byrne CD, Bonora E, Targher G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(2). https://doi.org/10.2337/dc17-1902.

- Younossi ZM, Golabi P, de Avila L, et al. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2019;71(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.021.

- Rhee EJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes: An epidemiological perspective. Endocrinol Metab. 2019;34(3). https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2019.34.3.226.

- Stevens GA, Singh GM, Lu Y, et al. * for the Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group (Body Mass Index). Popul Health Metr. 2012;10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7954-10-22.

- Wang D, Xu Y, Zhu Z, et al. Changes in the global, regional, and national burdens of NAFLD from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. Front Nutr. 2022;9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.1047129.

- Alswat K, Aljumah AA, Sanai FM, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease burden-Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates, 2017–2030. Saudi J Gastroentero. 2018;24(4). https://doi.org/10.4103/sjg.SJG_122_18.

- Wilson S, Chalasani N. Noninvasive Markers of Advanced Histology in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Are We There yet? Gastroenterology. 2007;133(4). https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.045.

- Yoneda M, Imajo K, Takahashi H, et al. Clinical strategy of diagnosing and following patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease based on invasive and noninvasive methods. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-017-1414-2.

- Juo YY, Livingston EH. Testing for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2019;322(18). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.10696.

- Singh SP, Barik RK. NonInvasive Biomarkers in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Are We There Yet? J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2020;10(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2019.09.006.

- Hagström H, Vessby J, Ekstedt M, Shang Y. 99% of patients with NAFLD meet MASLD criteria and natural history is therefore identical. J Hepatol. 2024;80(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.08.026.

- Lee JH, Kim D, Kim HJ, et al. Hepatic steatosis index: A simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.002.

- Amernia B, Moosavy SH, Banookh F, Zoghi G. FIB-4, APRI, and AST/ALT ratio compared to FibroScan for the assessment of hepatic fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Bandar Abbas, Iran. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-02038-3.

- Friedrich-Rust M, Ong MF, Martens S, et al. Performance of Transient Elastography for the Staging of Liver Fibrosis: A Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(4). https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.034.

- Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Siddiqui MS, et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77(5). https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000323.

- Ng CH, Chan KE, Chin YH, et al. The effect of diabetes and prediabetes on the prevalence, complications and mortality in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28(3). https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2022.0096.

- Kalan Farmanfarma KH, Ansari-Moghaddam A, Zareban I, Adineh HA. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Middle–East: Systematic review& meta-analysis. Prim Care Diabetes. 2020;14(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2020.01.003.

- Feldman H, ElSayed NA, McCoy RG, et al. Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin Diabetes. 2023;41(1). https://doi.org/10.2337/cd23-as01.

- Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43(6). https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.21178.

- Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38(2). https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2003.50346.

- Cusi K, Isaacs S, Barb D, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Primary Care and Endocrinology Clinical Settings: Co-Sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD). Endocr Pract. 2022;28(5):528-562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eprac.2022.03.010.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Ampuero J, Pais R, Aller R, et al. Development and Validation of Hepamet Fibrosis Scoring System–A Simple, Noninvasive Test to Identify Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease With Advanced Fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(1):216-225.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.051.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Lomonaco R, Leiva EG, Bril F, et al. Advanced liver fibrosis is common in patients with type 2 diabetes followed in the outpatient setting: The need for systematic screening. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):399-406. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-1997.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Shah AG, Lydecker A, Murray K, et al. Comparison of noninvasive markers of fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(10):1104-1112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.033.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Alqahtani SA, Golabi P, Paik JM, et al. Performance of Noninvasive Liver Fibrosis Tests in Morbidly Obese Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Obes Surg. 2021;31(5). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04996-1.

- Arab JP, Barrera F, Arrese M. The evolving role of liver biopsy in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2018;17(6). https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0012.7188.

- McPherson S, Stewart SF, Henderson E, Burt AD, Day CP. Simple non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can reliably exclude advanced fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2010;59(9). https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.216077.

- Chou R, Wasson N. Blood tests to diagnose fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(11). https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00005.

- Xiao G, Zhu S, Xiao X, Yan L, Yang J, Wu G. Comparison of laboratory tests, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance elastography to detect fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;66(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29302.

- Castera L, Friedrich-Rust M, Loomba R. Noninvasive Assessment of Liver Disease in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(5). https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.036.

- Petta S, Wong VWS, Cammà C, et al. Serial combination of non-invasive tools improves the diagnostic accuracy of severe liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(6). https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14219.

- Targher G, Corey KE, Byrne CD, Roden M. The complex link between NAFLD and type 2 diabetes mellitus — mechanisms and treatments. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(9). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-021-00448-y.

- Joo SK, Kim W, Kim D, et al. Steatosis severity affects the diagnostic performances of noninvasive fibrosis tests in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver International. 2018;38(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13549.

- Durazzo M, Marzari L, BoNetto S, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Diagnostic accuracy of different scores. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2021;66(4). https://doi.org/10.23736/S1121-421X.20.02753-1.

- Petta S, Maida M, Macaluso FS, et al. The Severity of Steatosis Influences Liver Stiffness Measurement in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Published online 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27844/suppinfo.

Article Google Scholar - Önnerhag K, Hartman H, Nilsson PM, Lindgren S. Non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can predict future metabolic complications and overall mortality in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2019.1583366.

- Phelps NH, Singleton RK, Zhou B, et al. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2024;403(10431). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02750-2.

Acknowledgements:

We are indebted to the Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences for their support of our research and to Dubai Health for granting access to patients and their records. The contributions of the medical and nursing staff at Dubai Diabetes Centre and Dubai Hospital are highly appreciated.

Funding

This study was supported by an internal grant (MBRU-CM-RG2019-06) awarded on May 29, 2019, by the College of Medicine, Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dubai, UAE, to Riad Bayoumi. Further support was obtained from Sandooq Al Watan (Grant Number, SWARD-F22-370 013) awarded on August 30, 2022, to Riad Bayoumi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Hepatology, King’s College Hospital London, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Farooq Khan MRCP - College of Medicine, Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Farooq Khan MRCP, Stafny Dsouza PhD, Fatima Abdul MD, Fatima Sulaiman MSc, Fahad Mulla MBBS & Riad Bayoumi PhD, FRCPath - Hamdan Bin Mohammed College of Dental Medicine, Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Amar Hassan Khamis PhD - Dubai Diabetes Center, Dubai Health, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Muhammad Hamed Farooqi MD - Endocrinology Department, Dubai Hospital, Dubai Health, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Fatheya Al Awadi MRCP & Mohammed Hassanein MRCP

Authors

- Farooq Khan MRCP

- Stafny Dsouza PhD

- Amar Hassan Khamis PhD

- Fatima Abdul MD

- Muhammad Hamed Farooqi MD

- Fatima Sulaiman MSc

- Fahad Mulla MBBS

- Fatheya Al Awadi MRCP

- Mohammed Hassanein MRCP

- Riad Bayoumi PhD, FRCPath

Contributions

FK: study design, patient recruitment, writing—review and editing.

SD: laboratory investigations, data analysis, writing—initial and editing.

AHK: data analysis-statistics, writing—review and editing.

FA: patient recruitment, data collection and recording.

MHF: patient recruitment.

FS: laboratory investigations.

FM: patient recruitment, data collection and recording.

FAA: patient recruitment.

MH: patient recruitment.

RB: conceptualization, study design, funding, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence toRiad Bayoumi PhD, FRCPath.

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests:

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in the submitted article are our own and not an official position of the institution or funder.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, F., Dsouza, S., Khamis, A.H. et al. Noninvasive Assessment of the Severity of Liver Fibrosis in MASLD Patients with Long-Standing Type 2 Diabetes.J GEN INTERN MED 40, 2309–2318 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2

- Received: 06 August 2024

- Accepted: 30 December 2024

- Published: 22 January 2025

- Version of record: 22 January 2025

- Issue date: July 2025

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-025-09348-2

KEY WORDS

Profiles

- Stafny Dsouza View author profile

- Amar Hassan Khamis View author profile

- Riad Bayoumi View author profile