Emerging therapies for HBsAg seroclearance: spotlight on novel combination strategies (original) (raw)

Abstract

Introduction

Functional cure is a favorable endpoint in chronic hepatitis B (CHB), yet it is rarely achieved with currently approved drugs (nucleos[t]ide analogues and pegylated interferon alpha). A range of novel agents, broadly classified into virus-targeting agents and immunomodulators, are hence developed with functional cure as the treatment target. As the data on individual novel agents are maturing, the field has gradually shifted to novel combination strategies.

Methods

This article comprehensively reviewed the data on novel combination strategies against CHB. Potential mechanisms and future developmental directions are also discussed

Results

RNA silencers (including antisense oligonucleotides and small-interfering RNAs) form the backbone of most combination strategies. Synergistic effects are observable with the combination of RNA silencers + single or dual immunomodulators, primarily through enhancing the magnitude and rate of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) decline, prolonging RNA silencer effects, and reducing HBsAg rebound after end-of-treatment. Accumulating data also demonstrate immune dysfunction recovery among patients with significant HBsAg reduction on RNA silencer-based or immune checkpoint inhibitor-based combination therapies.

Conclusion

Functional cure is now an attainable endpoint with novel combination treatment. Research is warranted to optimize combination regimens, and personalization of treatment strategies will be necessary. With further development, novel combination strategies have the potential to transform future CHB management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is one of the most prevalent chronic liver diseases globally. In 2024, 3.0% of the global population was infected by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), with HBV accounting for over 900,000 new hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases and 1.1-million liver-related mortalities [[1](/article/10.1007/s12072-025-10828-0#ref-CR1 "The CDA Foundation. Polaris Dashboard 2024. https://cdafound.org/polaris/dashboard/

.")\]. The global health burden of CHB is perpetuated by the unique viral features of covalently-closed circular DNA (cccDNA) and DNA integration \[[2](/article/10.1007/s12072-025-10828-0#ref-CR2 "Hui RW, Mak LY, Seto WK, Yuen MF. Assessing the developing pharmacotherapeutic landscape in hepatitis B treatment: a spotlight on drugs in phase II clinical trials. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2022;27(2):127–140")\], both of which preclude the complete and sterilizing cure of HBV. Instead of complete cure, an alternate endpoint that is currently achievable is functional cure, defined as sustained hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroclearance with unquantifiable HBV DNA at 24 weeks off treatment \[[3](/article/10.1007/s12072-025-10828-0#ref-CR3 "Ghany MG, Buti M, Lampertico P, Lee HM. Guidance on treatment endpoints and study design for clinical trials aiming to achieve cure in chronic hepatitis B and D: report from the 2022 AASLD-EASL HBV-HDV Treatment Endpoints Conference. Hepatology. 2023;78(5):1654–1673")\].Functional cure is associated with liver fibrosis regression [4, 5] and reduced HCC risks [6]. Furthermore, functional cure represents restored host immunity against HBV, and is considered as a quiescent disease phase [7]. Despite the allure of functional cure, it is a rarely achieved endpoint, and cannot be consistently induced by the currently approved HBV drugs of nucleos(t)ide analogs (NUCs) and pegylated interferon alpha (Peg-IFNα). NUCs, as the main HBV treatment option worldwide, can potently suppress HBV replication [7], but has minimal effects on HBsAg [8, 9]. In a large meta-analysis involving 34 studies and 42,588 patients, the annual HBsAg seroclearance rates were statistically comparable between NUC-treated and untreated patients (0.8% and 1.3%, respectively) [10].

With the limitations of current HBV drugs, a range of novel agents targeting functional cure are emerging. These novel agents can be broadly classified into virus-targeting agents—drugs that target distinct steps of the viral lifecycle, and immunomodulators—drugs that enhance host anti-HBV immune responses [2]. While the data on individual novel agents are maturing, newer trials have further established synergistic antiviral effects when combining these emerging drugs [11]. This article will review the latest evidence and discuss the role of emerging combination strategies for functional cure.

Novel agents in development

Virus-targeting agents

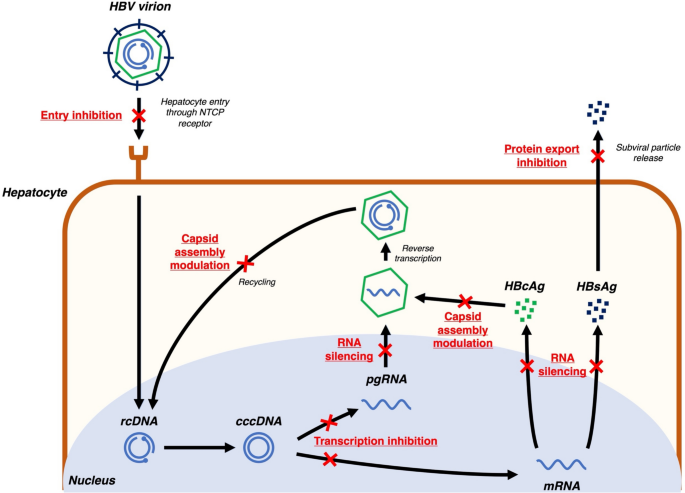

HBV is an enveloped partially double-stranded DNA virus with a relaxed circular DNA (rcDNA) genome of 3200 base pairs [12]. The HBV lifecycle has multiple druggable targets that have been studied for novel HBV therapies (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Novel virus-targeting agents against hepatitis B. cccDNA covalently closed circular DNA, HBcAg hepatitis B core antigen, HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen, HBV hepatitis B virus, mRNA messenger RNA, pgRNA pregenomic RNA, rcDNA relaxed circular DNA

First, since HBV interacts with sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) receptors for cellular uptake [13], competitive entry inhibitors of the NTCP receptor have been developed. Bulevirtide is the first-in-class entry inhibitor, which has primarily been studied and granted conditional approval for therapeutic use in Europe in HBV and hepatitis D virus (HDV) coinfected patients, as HDV has limited therapeutic targets [14]. However, there is still a lack of studies to assess bulevirtide in HBV mono-infected populations.

After HBV enters hepatocytes, it is uncoated and the viral rcDNA is transported to the hepatocyte nuclei. Using host cell repair mechanisms, the rcDNA is ligated to form cccDNA, which acts as a transcription template for viral messenger RNA (mRNA) and pregenomic RNA (pgRNA) [15]. This transcription step can be inhibited by modulation of farnesoid X receptors (FXR), which in turn inhibit downstream viral replication. Selective FXR agonists such as vonafexor have been studied in phase II clinical trials [16].

HBV mRNAs are translated to multiple viral proteins including HBsAg, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg), HBV X protein, and HBV polymerase [15]. RNA silencers, including small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), are designed with complementary nucleotide sequences to conserved regions of the HBV genome, enabling effective silencing of mRNA translation [17]. With the potent suppression of mRNA translation, RNA silencers reduce circulating viral protein levels, indirectly enhancing host immune reconstitution against HBV [18]. Furthermore, RNA silencers can inhibit downstream pgRNA activity, in turn inhibiting viral replication [17]. RNA silencers are the most advanced drug class in development when compared with other novel drug candidates. Multiple agents including bepirovirsen (ASO), daplusiran/tomligisiran (siRNA, also known as JNJ-3989), elebsiran (siRNA, also known as VIR-2218), imdusiran (siRNA, also known as AB-729), RBD-1016 (siRNA), and xalnesiran (siRNA, also known as RO7445482) have entered phase II or III trials [19]. Details on therapeutic targets and treatment efficacy of ASOs and siRNAs are described in Table 1 [20,21,22,23,24,25].

Table 1 Targets and treatment efficacy of RNA silencers

HBcAg is one of the viral proteins translated from HBV mRNA, and is an important component of HBV nucleocapsids [26]. Capsid assembly modulators (CAMs) interfere with HBcAg to induce formation of aberrant nucleocapsids (CAM-A action) or empty nucleocapsids (CAM-E action)—constituting their primary action [27]. CAMs also have a secondary mode of action in stimulating mistimed uncoating of nucleocapsids, which interferes with cccDNA recycling [[28](/article/10.1007/s12072-025-10828-0#ref-CR28 "Berke JM, Dehertogh P, Vergauwen K, Van Damme E, Mostmans W, Vandyck K, et al. Capsid assembly modulators have a dual mechanism of action in primary human hepatocytes infected with hepatitis B virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00560-17

")\]. ALG-000184 is a newer generation CAM with both the strongest primary and secondary modes of action among all developing CAMs, and its development has entered phase II \[[29](/article/10.1007/s12072-025-10828-0#ref-CR29 "Yuen MF, Gane E, Schwabe C, Jucov A, Haceatrean A, Wu M, et al. Monotherapy with the capsid assembly modulator, ALG-000184, results in high viral suppression rates in untreated HBeAg+ and HBeAg- subjects with chronic heaptitis B infection. Hepatology. 2024;80:S166–S167")\].HBsAg, aside from being the key component of the viral envelope, is also released into the circulation as subviral particles [15]. Nucleic acid polymers (NAPs) such as REP2139 and REP2165 are effective in blocking subviral particle export from hepatocytes, in turn reducing HBsAg levels [30].

Immunomodulators

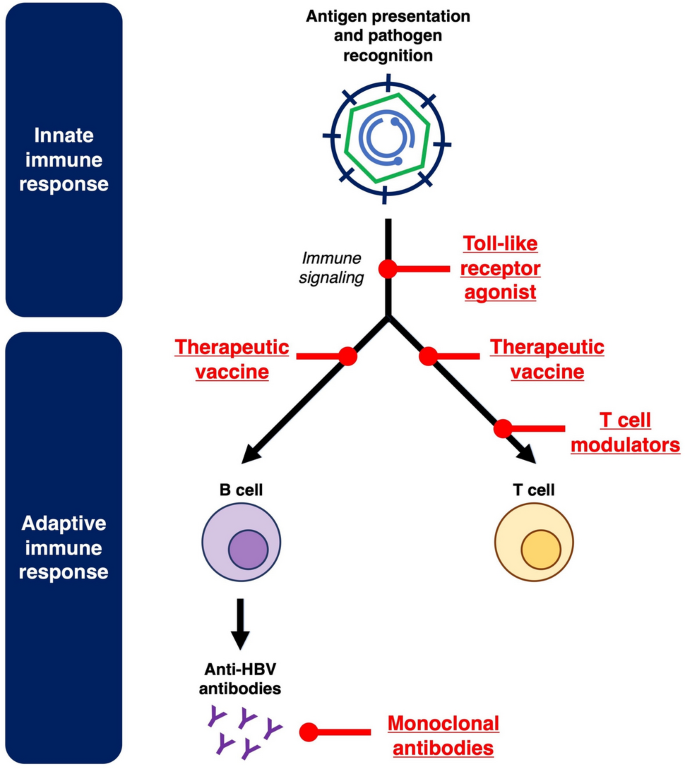

Host immunotolerance is a well-established pathogenic mechanism contributing to CHB. Both innate and adaptive immune responses can be influenced by prolonged exposure to HBsAg and other viral proteins, ultimately resulting in immune dysfunction and chronic HBV persistence [31, 32]. Immunomodulators target the host immune system to reverse immunotolerance and stimulate anti-HBV immune responses. The key immunomodulatory pathways targeted in novel CHB treatment are depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2

Novel immunomodulators against hepatitis B

First, toll-like receptors (TLRs) are critical for pathogen recognition in the innate immune system [[33](/article/10.1007/s12072-025-10828-0#ref-CR33 "Mifsud E, Tan A, Jackson D. TLR agonists as modulators of the innate immune response and their potential as agents against infectious disease. Front Immunol. 2014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2014.00079

")\]. TLR7 and TLR8 agonists, which can stimulate downstream cytokine release and immune signaling, have both been studied as novel agents against CHB \[[34](/article/10.1007/s12072-025-10828-0#ref-CR34 "Janssen HL, Lim YS, Kim HJ, Sowah L, Tseng CH, Coffin CS, et al. Safety, pharmacodynamics, and antiviral activity of selgantolimod in viremic patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. JHEP Rep. 2024;6(2): 100975"), [35](/article/10.1007/s12072-025-10828-0#ref-CR35 "Agarwal K, Ahn SH, Elkhashab M, Lau AH, Gaggar A, Bulusu A, et al. Safety and efficacy of vesatolimod (GS-9620) in patients with chronic hepatitis B who are not currently on antiviral treatment. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(11):1331–1340")\].Therapeutic vaccination has been studied as a strategy to generate active immunity against HBV. While older therapeutic vaccines adopted HBsAg as the main constituent [36], newer data supports the incorporation of other viral proteins. These newer generation therapeutic vaccines such as BRII-179 (consisting of 3 HBV surface antigens PreS1, PreS2 and S) [37] and VTP-300 (consisting of polymerase, core, entire S region) [38] have entered phase II trials. In contrast to active immunity through vaccination, passive immunity through administration of anti-HBV monoclonal antibodies is another strategy that has been studied. In addition, these monoclonal antibodies exert some vaccinal effects [39, 40]. With the emergence of mRNA vaccine technology, therapeutic HBV vaccines on mRNA platforms have also been developed. Nonetheless, these mRNA vaccines remain in in-vitro and animal studies, and have yet to be studied in clinical trials [41,42,43].

Finally, immunomodulators against T cells have been studied to reverse T cell dysfunction in CHB [32]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors against the Programmed cell death protein 1/Programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD1/PDL1) pathway have entered clinical trials for CHB [44, 45]. Novel techniques such as Inhibitors of apoptosis (IAP) antagonists and immune mobilizing monoclonal T cell receptors against virus (ImmTAV) are other T cell modulators that have been studied [46, 47].

An overview on the developmental landscape for novel agents

The treatment efficacy from novel agent monotherapies is summarized in Tables 1 and 2 [48]. Currently, RNA silencers are the most promising novel agents in development, demonstrating potent and sustainable HBsAg suppression [49]. HBsAg seroclearance has also been documented with RNA silencer therapy, although this is mostly seen in patients with lower baseline HBsAg (< 1000 IU/ml) [20]. RNA silencers will likely form the backbone for future HBV therapy. CAMs are another drug class with encouraging trial results. ALG-000184, a newer generation CAMs, can induce deeper HBV DNA suppression than NUCs alone, and has also shown HBsAg reduction effects [29]. In contrast to virus-targeting agents, immunomodulators are generally less potent in HBsAg suppression, and have limited roles in monotherapy.

Table 2 Overview on novel agents outside of RNA silencers

Based on the current trial results, no novel agents can consistently induce functional cure at high rates as monotherapy. While HBsAg reduction is a key study outcome in multiple clinical trials, HBsAg suppression alone does not guarantee subsequent HBsAg seroclearance. Host immune response boosting, either directly by immunomodulators or indirectly via viral antigen reduction, is also essential for HBsAg seroclearance. Interest in combination strategies of novel agents has hence grown, as combination treatment can target multiple pathways concurrently to yield synergistic antiviral effects. The following sections will provide an in depth review on combination strategies in clinical trials.

Combination strategies in clinical trials

Combination of virus-targeting agents

siRNAs and CAMs, as two of the most well-studied novel drug classes, have been studied in multiple combination trials (Table 3). The REEF-1 and REEF-2 trials both studied the combination of daplusiran/tomligisiran (siRNA) + bersacapavir (CAM).

Table 3 Combination strategies with novel agents

In the REEF-1 trial, patients were randomized to daplusiran/tomligisiran 100 mg + bersacapavir 250 mg, daplusiran/tomligisiran monotherapy (200 mg, 100 mg, or 40 mg arms), or bersacapavir 250 mg monotherapy for 48 weeks. The primary endpoint of the trial was a predetermined criteria for NUC withdrawal—HBsAg < 10 IU/ml, unquantifiable HBV DNA, and ALT < 3 × upper limit normal). Treatment efficacy appeared to depend on daplusiran/tomligisiran dosing. The daplusiran/tomligisiran 200 mg monotherapy group achieved the best results with end-of-treatment (EOT) HBsAg decline of 2.6 log IU/ml, with 19% of patients achieving the primary endpoint. In comparison, the daplusiran/tomligisiran 100 mg + bersacapavir 250 mg combination group achieved EOT HBsAg decline by 1.8 log IU/ml, with 9% achieving the primary endpoint. In the daplusiran/tomligisiran 100 mg monotherapy group, EOT HBsAg decline was 2.1 log IU/ml, with 16% achieving the primary endpoint. Three daplusiran/tomligisiran monotherapy patients (2 in the 200 mg arm and 1 in the 100 mg arm) achieved HBsAg seroclearance at 24 weeks post-EOT, whereas no patients on combination therapy achieved HBsAg seroclearance [50].

The REEF-2 trial studied daplusiran/tomligisiran 200 mg + bersacapavir 250 mg in NUC-treated patients, whereas the control arm received placebo. All treatment including NUCs were stopped after 48 weeks. 46.9% on combination treatment achieved HBsAg < 100 IU/ml at 48 weeks post-EOT, while only 15.0% of control patients achieved HBsAg < 100 IU/ml. No patients in the active or control arms achieved HBsAg seroclearance. As secondary endpoints, combination treatment reduced biochemical flares (3.6% vs 28.6% in controls) and also reduced the necessity to resume NUCs (9.1% vs 26.8% in controls) [51].

In the phase II trial of imdusiran (siRNA) + vebicorvir (CAM), combination treatment was compared against imdusiran monotherapy and vebicorvir monotherapy, respectively. After 48 weeks of treatment, 61.5% of patients on combination therapy achieved a predefined criteria to stop NUCs (HBsAg < 100 IU/ml, unquantifiable HBV DNA, and ALT < 2 × upper limit normal). In contrast, this stop NUC criteria was achieved in 80.0% of patients on imdusiran monotherapy and in 0% of patients on vebicorvir monotherapy [52].

According to the above findings, HBsAg reduction with the combination of siRNAs + CAMs was primarily driven by siRNA, and the addition of CAMs to siRNAs did not yield synergistic therapeutic effects.

Combination of immunomodulators

Monotherapy with immunomodulators generally result in modest effects on HBsAg. Nonetheless, combining immune checkpoint inhibitors or therapeutic vaccines with other immunomodulators may concurrently boost the abundance and function of immune cells, in turn augmenting HBsAg suppressive effects.

VTP-300 is a therapeutic vaccine targeting HBsAg, HBcAg and HBV polymerase. It is a prime-boost vaccine, with the prime dose given at baseline and the boost dose given on day 28 [38]. A phase II trial studied different dosing regimens of nivolumab (anti PD1) in combination with VTP-300. The trial included patients receiving VTP-300 monotherapy, and also involved two combination arms with VTP-300 + nivolumab. Among the combination arms, one arm in the trial received a single dose of nivolumab with the boost dose vaccine (day 28), and the other arm received two doses of nivolumab with the prime (day 0) and boost (day 28) doses, respectively. The treatment efficacy was superior in patients who received VTP-300 + a single dose of day 28 nivolumab, as the group achieved mean HBsAg reduction of 0.76 log IU/ml at 2 months post-EOT, with 11.1% (2 out of 18 patients) attaining HBsAg seroclearance. The 2 patients who achieved HBsAg seroclearance had baseline HBsAg level of 61 IU/ml and 43 IU/ml respectively. Conversely, no significant HBsAg reduction or HBsAg seroclearance was achieved in patients who received VTP-300 with 2 nivolumab doses [38].

The ongoing HBV003 trial is studying VTP-300 + nivolumab in patients with baseline HBsAg < 200 IU/ml. At interim analysis, 11.6% of patients (8 out of 69) achieved HBsAg seroclearance, with 2 patients achieving anti-HBs seroconversion. Among 9 patients who discontinued NUCs at week 24 of the trial, 2 patients remained HBsAg negative, reaching the criteria for functional cure [53].

The trials on VTP-300 and nivolumab highlight the intricate interactions between different immunomodulators. While nivolumab can be synergistic with therapeutic vaccines, administration of nivolumab at specific timings may interfere with T cell activity to negate vaccinal effects.

BRII-179, another therapeutic vaccine, has been studied in combination with Peg-IFNα. This combination regimen successfully induced both T cell and antibody responses, yet it did not lead to significant HBsAg reduction [37].

The OCEANcure05 study is a phase II RCT studying the combination of TQ-B2450 (anti PDL1 monoclonal antibody) + TQ-A3334 (selective TLR7 agonist). This combination + NUC for 24 weeks led to mean EOT HBsAg reduction by 0.45 log IU/ml. In contrast, the EOT HBsAg reduction was 0.03 log IU/ml in the TQ-A3334 + NUC group, and 0.04 log IU/ml in the NUC only control group. The combination therapy also led to higher HBV RNA and HBeAg reduction compared to the other arms [54].

A recent open-label trial studied different combinations of immunomodulators, including nivolumab monotherapy, nivolumab + selgantolimod (TLR8 agonist), and GS4224 (a novel small-molecular PDL1 inhibitor) + selgantolimod. As HBsAg suppression was previously observed in HBV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) co-infected patients treated with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, this trial also included a treatment arm with nivolumab + ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. Patients on nivolumab + ledipasvir/sofosbuvir had modest HBsAg decline by 0.44 log IU/ml at EOT, which rebounded to baseline after EOT. The other treatment arms did not have significant HBsAg decline during treatment. The primary endpoint (≥ 0.5 log IU/ml HBsAg decline from baseline to week 8 post-EOT) was only achieved in 1 patient (9%) in the nivolumab + ledipasvir/sofosbuvir arm and in 1 patient (8%) in the nivolumab + selgantolimod arm [55]. Sustained elevation of peripheral inflammatory cytokines and chemokines was observed in nivolumab monotherapy and in nivolumab + selgantolimod, suggesting target engagement [55]. This trial also demonstrated the potential effects of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir on HBsAg, although formal repurposing of this HCV drug for HBV treatment will require further validation.

Combination of RNA silencers with Peg-IFNα

RNA silencers are the most potent virus-targeting agents in development [20, 49], and they have been the backbone in different combination strategies. The combination of RNA silencers + immunomodulators targets both the virus and the host, and should theoretically attain maximal therapeutic effects. RNA silencers can also induce immune reconstitution through reducing viral protein levels, in turn boosting the efficacy of immunomodulators. Among RNA silencer + immunomodulator combinations, multiple studies have been performed on Peg-IFNα—an approved drug for CHB.

Bepirovirsen (ASO) has been studied in combination with Peg-IFNα in NUC-treated patients in the B-Together trial. The primary outcome of the trial was undetectable HBsAg with unquantifiable HBV DNA at 24 weeks post-EOT. Among patients who received bepirovirsen 300-mg weekly (with loading doses) for 24 weeks followed by 24 weeks of Peg-IFNα, 9% (5 out of 55) achieved the primary outcome. Whereas among patients who received bepirovirsen 300 mg weekly (with loading doses) for 12 weeks followed by 24 weeks of Peg-IFNα, 15% (8 out of 53) achieved the primary outcome. All patients achieving the primary outcome had baseline HBsAg < 3000 IU/ml. When compared with data from the bepirovirsen monotherapy trial, Peg-IFNα reduced HBsAg rebound after EOT, yet had no effect on maximal HBsAg suppression [56].

A phase II trial studied the combination of xalnesiran + Peg-IFNα or ruzotolimod (TLR7 agonist) in NUC-treated patients. The primary endpoint of the study was HBsAg seroclearance at 24 weeks after EOT. In the xalnesiran + Peg-IFNα arm, patients simultaneously received xalnesiran 200 mg every 4 weeks + weekly Peg-IFNα for 48 weeks total. Whereas in the xalnesiran + ruzotolimod arm, patients received xalnesiran 200 mg every 4 weeks for 48 weeks + alternate day ruzotolimod 150 mg from weeks 13–24 and from weeks 37–48. The primary endpoint occurred in 23% of patients in the Peg-IFNα combination arm and in 12% in the ruzotolimod combination arm, which was superior to the effects in the xalnesiran monotherapy groups (7% in xalnesiran 100-mg group and 3% in xalnesiran 200 mg group). Baseline HBsAg was a key determinant of treatment effects, as HBsAg seroclearance only occurred in patients with baseline HBsAg < 3 log IU/ml. [57]

Elebsiran (siRNA) + Peg-IFNα has been studied in NUC-treated patients in phase II trials. Among 69 patients who received elebsiran (ranging from 6–13 doses) + Peg-IFNα (ranging from 12–48 doses), mean maximum HBsAg reduction by 1.7–3.0 log IU/ml was achieved. 15.9% of patients (11 out of 69) achieved undetectable HBsAg during the study, and only 6 patients had sustained HBsAg seroclearance at 24 weeks post-EOT. No patients receiving elebsiran monotherapy achieved HBsAg seroclearance [58].

Similar results have been demonstrated in another phase II trial on elebsiran (100 or 200 mg) + Peg-IFNα. In the combination therapy arms, 29.7% of patients (11 out of 37) achieved EOT HBsAg seroclearance. In contrast, only 5.6% (1 out of 18) on Peg-IFNα monotherapy achieved EOT HBsAg seroclearance. The addition of Peg-IFNα to elebsiran increased both the magnitude and rate of HBsAg suppression. All patients who achieved HBsAg seroclearance had baseline HBsAg < 1500 IU/ml [59].

The IM-PROVE I trial studied imdusiran (siRNA) + Peg-IFNα in HBeAg negative NUC-treated patients. Among 25 patients who received 24 weeks of Peg-IFNα, 28% of patients (7 out of 25) achieved undetectable HBsAg at EOT, with 6 of these 7 subjects having sustained HBsAg seroclearance at 24 weeks post-EOT. In contrast, no patients in the 12-week Peg-IFNα cohorts achieved HBsAg seroclearance. Overall, 21 patients met the stop NUC criteria (HBsAg < 100 IU/ml, undetectable HBV DNA, and ALT < 2 × upper limit normal) at 24 weeks after EOT, with only 5 patients requiring resumption of NUCs [60].

In contrast to other siRNA + Peg-IFNα trials which focused on NUC-treated patients, the REEF-IT trial (daplusiran/tomligisiran + Peg-IFNα) focused on immunotolerant patients with baseline HBV DNA > 4 log IU/ml. HBsAg seroclearance was achieved in 20.3% of patients (11 out of 54) at one or more timepoints in the trial, and 6 of these patients were still HBsAg negative at the last observed timepoint at interim analysis (up to 48 weeks post-EOT). Notably, the addition of Peg-IFNα primarily exerted its effect through accelerating HBsAg decline. [61]

Combination of RNA silencers with therapeutic vaccines

The IM-PROVE II trial studied the combination of imdusiran + VTP-300 in NUC treated CHB patients. In the combination arm, 94.7% of patients (18 out of 19) achieved HBsAg < 100 IU/ml at EOT, while only 84.2% (16 out of 19) on imdusiran monotherapy achieved this outcome [62]. Overall, the addition of VTP-300 led to more sustained HBsAg suppressive effects from imdusiran. This trial had a further arm with addition of nivolumab on top of imdusiran + VTP-300. At EOT, 92.3% of patients (12 out of 13) on imdusiran + VTP-300 + nivolumab achieved HBsAg < 100 IU/ml, with 3 patients (23.1%) attaining undetectable EOT HBsAg [63].

The OSPREY trial is an ongoing phase Ib trial on the combination of daplusiran/tomligisiran + JNJ-0535 (therapeutic vaccine). At EOT, the combination treatment led to mean HBsAg decline by 2.18 log IU/ml. The combination treatment showed successful upregulation of HBV-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells, and a further stop NUC phase is ongoing for this study [64]. Elebsiran + BRII-179 (therapeutic vaccine) is another combination that has entered phase II trials, with combination therapy inducing mean HBsAg reduction by 1.7 log IU/ml at EOT [65].

Combination of RNA silencers with T cell modulators

The combination of xalnesiran with RO7191863 (a PD-L1 locked nucleic acid [LNA]) has been studied in NUC-treated patients. A concurrent regimen (xalnesiran every 4 weeks for 24 weeks + RO7191863 weekly from weeks 13–24) and sequential regimen (xalnesiran every 4 weeks for 24 weeks + RO7191863 weekly from weeks 25–36) were studied, and both regimens led to comparable HBsAg suppression. At EOT, 6.1% of patients (2 out of 33) in the concurrent arm and 12.9% (4 out of 31) in the sequential arm achieved HBsAg seroclearance. Only 2 patients (6.5%) from the sequential arm had sustained HBsAg seroclearance at 24 weeks post-EOT [66].

The OCTOPUS-1 trial is a phase II trial studying the combination of daplusiran/tomligisiran + nivolumab in NUC-treated patients. At EOT, the combination regimen led to mean HBsAg reduction by 2.01–2.10 log IU/ml. The HBsAg levels remained at 1.70–1.85 log IU/ml below baseline at 24 weeks post-EOT, with 72–84% of patients remaining at HBsAg < 100 IU/ml at 24 weeks post-EOT [67].

The combination of elebsiran + nivolumab + selgantolimod (TLR8 agonist) is currently studied in a phase II trial. The triple drug regimen led to HBsAg loss at 24 weeks post-EOT in 2.5% of patients (1 out of 40) who were not on NUCs at baseline. In contrast, none of the non-NUC patients on nivolumab + selgantolimod achieved HBsAg loss. Off-treatment rebound in HBsAg was noted after completion of elebsiran [68].

Combination of RNA silencers with monoclonal antibodies

The phase II MARCH trial studied the combination of elebsiran + tobevibart (monoclonal antibodies), with or without Peg-IFNα for up to 48 weeks. Among patients with baseline HBsAg < 1000 IU/ml, 38.9% (7 out of 18 patients) on elebsiran + tobevibart and 45.5% (5 out of 11 patients) on elebsiran + tobevibart + Peg-IFNα achieved HBsAg seroclearance at EOT. No patients on tobevibart monotherapy achieved HBsAg seroclearance. The triple combination regimen enhanced the sustainability of HBsAg suppression after EOT [69].

Evidence of immune dysfunction recovery

In some of the aforementioned trials, recovery of host immune function alongside HBsAg reduction was evidenced by upregulation of soluble inflammatory markers such as IL-2 and IL-6 (e.g., in imdusiran + PEG-IFNα [60]; and in nivolumab + selgantolimod or ledipasvir/sofosbuvir [55]), anti-HBs seroconversion with or without rising titers (e.g., in elebsiran + tobevibart ± PEG-IFNα [69]), and HBV-specific T-cell responses (e.g., in VIR-2218 + selgantolimod + nivolumab [68]). However, these responses were not always associated with HBsAg seroclearance. The association between treatment-induced immune upregulation and functional cure remains unclear, and further research in this area is warranted.

Discussion

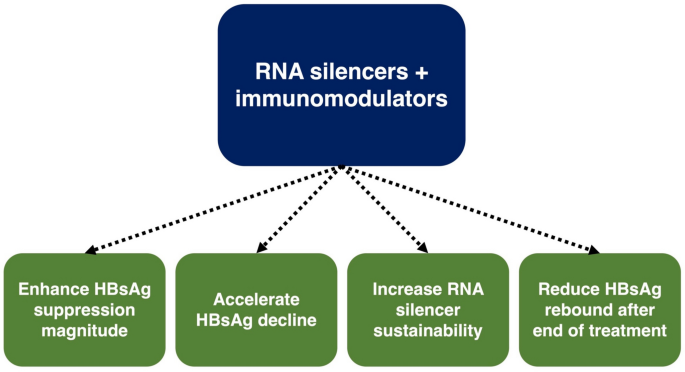

This article summarized the numerous completed and ongoing trials on novel combination strategies. The study results are promising, and functional cure is now an attainable target with combination treatment. RNA silencers have been the backbone of most combination strategies, and the addition of immunomodulator adjuncts yields synergistic antiviral effects. Immunomodulators enhance the magnitude of HBsAg suppression [59], accelerate HBsAg decline [61], sustain RNA silencer effects [62, 69], and reduce post-EOT HBsAg rebound [56] (Fig. 3). The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors with another immunomodulator is also gaining popularity in clinical trials for HBV infection.

Fig. 3

Effects from combining RNA silencers with immunomodulators

Despite the encouraging results, the current trials highlighted that combination strategies require complex design, and patients should not be blindly prescribed a cocktail of drugs. The trials on xalnesiran + RO7191863 [66] and VTP-300 + nivolumab [38] highlighted that the timing of drug administration may influence outcomes, as treatment effects can be negated by drug interactions. Conversely, appropriate design of treatment sequences can leverage the immune reconstitution effects of RNA silencers to potentiate immunomodulator effects [18, 70]. Aside from treatment sequence, the optimal drug dosage and treatment durations also warrant further research. The evidence from current trials will enable optimization of combination treatment strategies, and subsequent validation in larger phase III trials is required.

Lower pre-treatment HBsAg consistently predicted HBsAg seroclearance in monotherapy with novel agents [20, 38, 44], and this association was enhanced in combination treatment trials [56, 57, 59]. Yet aside from baseline HBsAg, our understanding on treatment response predictors remains limited. Other virological markers such as longitudinal qHBsAg kinetics [71,72,73], HBV RNA [74], and hepatitis B core related antigen (HBcrAg) [75] can predict HBsAg seroclearance in CHB patients, but have not been specifically studied in novel therapy. The combined use of different HBV biomarkers for predicting HBsAg seroclearance in novel therapies should be explored [76]. With the importance of host immunity in CHB, immune markers may also predict HBsAg seroclearance [77,78,79]. Both peripheral blood and intrahepatic immunology markers have been studied as predictors of treatment responses to novel therapies, although these studies remain exploratory in nature [80, 81]. Identification of response predictors will influence patient selection for combination treatment, and is hence an important area of research.

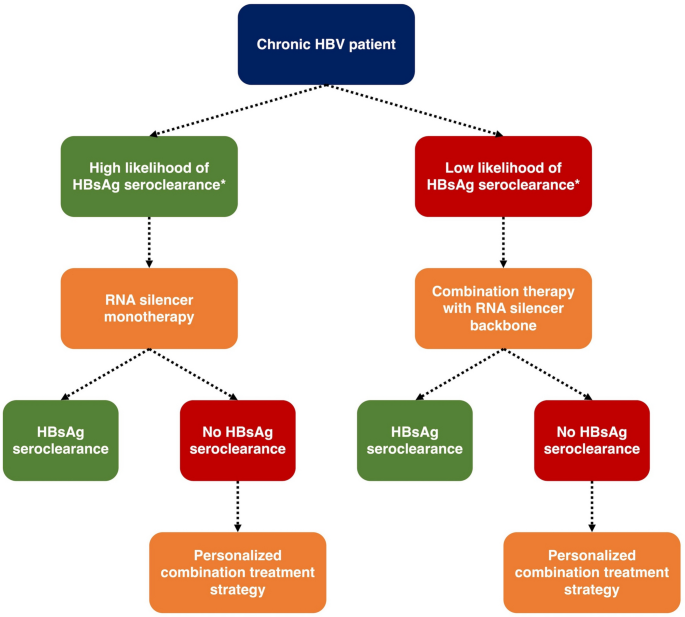

The future of CHB treatment will likely involve personalized design of drug regimens. In patients with high likelihood of HBsAg seroclearance (i.e., low baseline HBsAg plus other favorable immunology markers), a single course of ASO or siRNA monotherapy may already be sufficient to induce HBsAg seroclearance. Conversely in patients with low likelihood of treatment response (i.e., high baseline HBsAg plus unfavorable immunology markers), the use of RNA silencers plus immunomodulator adjuncts may be required. The type, number, and administration timing (i.e., concomitantly or sequential) of immunomodulator adjuncts should be further deliberated on an individual patient basis. Our proposed treatment algorithm is summarized in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4

Proposed treatment algorithm with novel therapies. *Further studies are required to assess the predictors of HBsAg seroclearance. Virological factors (including qHBsAg, HBcrAg and HBV RNA) and immunologic factors (including cytokine and immune cell profiles) will both have important roles for prediction and personalization of treatment strategies

Patient tolerability is another important consideration in combination treatment, as patients will inevitably be exposed to adverse effects of 2 or more drugs. RNA silencers are generally safe and well tolerated, although treatment-emergent adverse events such as injection site reactions and flu-like symptoms are common [19]. Peg-IFNα—a drug notorious for its poor tolerability, also has a prominent role in combination strategies, and will certainly influence patient tolerability. Taking the xalnesiran + Peg-IFNα or ruzotolimod trial as an example, treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 100% of patients in the xalnesiran + Peg-IFNα arm and in 76% of patients in the xalnesiran + ruzotolimod arm [57]. Similarly in the elebsiran + Peg-IFNα trial, treatment-emergent adverse events were common in the cohorts that received the largest number of Peg-IFNα doses (83% in cohort 4 [6 doses of elebsiran + up to 48 doses of Peg-IFNα]; 100% in cohort 5 [up to 13 doses of elebsiran + up to 44 doses of Peg-IFNα]) [58]. Careful patient counseling and close monitoring will be necessary in combination treatment. A limitation of current clinical trials is the inclusion of highly selected patient cohorts. Trials generally exclude patients with cirrhosis or other medical comorbidities. Elderly patients or patients with relatively high qHBsAg (> 3000 IU/ml) were also excluded. The accumulation of real-world safety data will be necessary prior to widespread application of novel combination therapies.

To conclude, novel combination strategies for CHB are emerging. RNA silencers + immunomodulators have demonstrated promising results, and functional cure is now attainable. With further development, novel combination strategies have the potential to transform future CHB management.

References

- The CDA Foundation. Polaris Dashboard 2024. https://cdafound.org/polaris/dashboard/.

- Hui RW, Mak LY, Seto WK, Yuen MF. Assessing the developing pharmacotherapeutic landscape in hepatitis B treatment: a spotlight on drugs in phase II clinical trials. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2022;27(2):127–140

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ghany MG, Buti M, Lampertico P, Lee HM. Guidance on treatment endpoints and study design for clinical trials aiming to achieve cure in chronic hepatitis B and D: report from the 2022 AASLD-EASL HBV-HDV Treatment Endpoints Conference. Hepatology. 2023;78(5):1654–1673

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Mak LY, Seto WK, Hui RW, Fung J, Wong DK, Lai CL, et al. Fibrosis evolution in chronic hepatitis B e antigen-negative patients across a 10-year interval. J Viral Hepatitis. 2019;26(7):818–827

Article CAS Google Scholar - Mak LY, Hui RW, Chung MSH, Wong DK, Fung J, Seto WK, et al. Regression of liver fibrosis after HBsAg loss: a prospective matched case-control evaluation using transient elastography and serum enhanced liver fibrosis test. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;39:2826–2834

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hui RW, Mak LY, Cheung TT, Lee VH, Seto WK, Yuen MF. Clinical practice guidelines and real-life practice on hepatocellular carcinoma: the Hong Kong perspective. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;29(2):217–229

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hui RW, Mak LY, Seto WK, Yuen MF, Fung J. Chronic hepatitis B: a scoping review on the guidelines for stopping nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;17(5):443–450

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zoutendijk R, Hansen BE, van Vuuren AJ, Boucher CA, Janssen HL. Serum HBsAg decline during long-term potent nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy for chronic hepatitis B and prediction of HBsAg loss. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(3):415–418

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chevaliez S, Hézode C, Bahrami S, Grare M, Pawlotsky JM. Long-term hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) kinetics during nucleoside/nucleotide analogue therapy: finite treatment duration unlikely. J Hepatol. 2013;58(4):676–683

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yeo YH, Ho HJ, Yang HI, Tseng TC, Hosaka T, Trinh HN, et al. Factors associated with rates of HBsAg seroclearance in adults with chronic HBV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(3):635–646

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hui RW, Mak LY, Cheung KS, Fung J, Seto WK, Yuen MF. Novel combination strategies with investigational agents for functional cure of chronic hepatitis B infection. Curr Hepat Rep. 2022;21(4):59–67

Article Google Scholar - Yuen MF, Lai CL. Hepatitis B in 2014: HBV research moves forward–receptors and reactivation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(2):70–72

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Park JH, Iwamoto M, Yun JH, Uchikubo-Kamo T, Son D, Jin Z, et al. Structural insights into the HBV receptor and bile acid transporter NTCP. Nature. 2022;606(7916):1027–1031

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wedemeyer H, Aleman S, Brunetto MR, Blank A, Andreone P, Bogomolov P, et al. A phase 3, randomized trial of bulevirtide in chronic hepatitis D. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(1):22–32

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mak LY, Hui RW, Fung J, Seto WK, Yuen MF. The role of different viral biomarkers on the management of chronic hepatitis B. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29(2):263–276

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Erken R, Andre P, Roy E, Kootstra N, Barzic N, Girma H, et al. Farnesoid X receptor agonist for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B: a safety study. J Viral Hepat. 2021;28(12):1690–1698

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hui RW, Mak LY, Seto WK, Yuen MF. RNA interference as a novel treatment strategy for chronic hepatitis B infection. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28:408–424

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Michler T, Kosinska AD, Festag J, Bunse T, Su J, Ringelhan M, et al. Knockdown of virus antigen expression increases therapeutic vaccine efficacy in high-titer hepatitis B virus carrier mice. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):1762–75.e9

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hui RW, Mak LY, Seto WK, Yuen MF. Investigational RNA interference agents for hepatitis B. BioDrugs. 2024;39:21–32

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yuen MF, Lim SG, Plesniak R, Tsuji K, Janssen HLA, Pojoga C, et al. Efficacy and safety of bepirovirsen in chronic hepatitis B infection. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(21):1957–1968

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yuen MF, Locarnini S, Lim TH, Strasser SI, Sievert W, Cheng W, et al. Combination treatments including the small-interfering RNA JNJ-3989 induce rapid and sometimes prolonged viral responses in patients with CHB. J Hepatol. 2022;77(5):1287–1298

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Gane E, Lim YS, Kim JB, Jadhav V, Shen L, Bakardjiev AI, et al. Evaluation of RNAi therapeutics VIR-2218 and ALN-HBV for chronic hepatitis B: results from randomized clinical trials. J Hepatol. 2023;79(4):924–932

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yuen MF, Holmes J, Strasser SI, Leerapun A, Sukeepaisarnjaroen W, Tangkijvanich P, et al., editors. 48 weeks of AB-729 + nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA) therapy results in profound, sustained HBsAg declines in both HBeAg+ and HBeAg- subjects which are maintained in HBeAg- subjects who have discontinued all therapy. Global Hepatitis Summit; 2023; Paris, France.

- Seto WK, Liang Z, Gan LM, Fu J, Yuen MF. Safety and antiviral activity of RBD1016, a RNAi therapeutic, in Chinese subjects with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. J Hepatol. 2023;78(S1):S1152

Article Google Scholar - Gane EJ, Kim W, Lim TH, Tangkijvanich P, Yoon JH, Sievert W, et al. First-in-human randomized study of RNAi therapeutic RG6346 for chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2023;79(5):1139–1149

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hui RW, Mak LY, Seto WK, Yuen MF. Role of core/capsid inhibitors in functional cure strategies for chronic hepatitis B. Curr Hepat Rep. 2020;19(3):293–301

Article Google Scholar - Mak LY, Hui RW, Seto WK, Yuen MF. Novel drug development in chronic hepatitis B infection: capsid assembly modulators and nucleic acid polymers. Clin Liver Dis. 2023;27(4):877–893

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Berke JM, Dehertogh P, Vergauwen K, Van Damme E, Mostmans W, Vandyck K, et al. Capsid assembly modulators have a dual mechanism of action in primary human hepatocytes infected with hepatitis B virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00560-17

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yuen MF, Gane E, Schwabe C, Jucov A, Haceatrean A, Wu M, et al. Monotherapy with the capsid assembly modulator, ALG-000184, results in high viral suppression rates in untreated HBeAg+ and HBeAg- subjects with chronic heaptitis B infection. Hepatology. 2024;80:S166–S167

Google Scholar - Bazinet M, Pântea V, Placinta G, Moscalu I, Cebotarescu V, Cojuhari L, et al. Safety and efficacy of 48 weeks REP 2139 or REP 2165, tenofovir disoproxil, and pegylated interferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic HBV infection naïve to nucleos(t)ide therapy. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(8):2180–2194

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zheng P, Dou Y, Wang Q. Immune response and treatment targets of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: innate and adaptive immunity. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1206720

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Park JJ, Wong DK, Wahed AS, Lee WM, Feld JJ, Terrault N, et al. Hepatitis B virus-specific and global T-cell dysfunction in chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(3):684–95.e5

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mifsud E, Tan A, Jackson D. TLR agonists as modulators of the innate immune response and their potential as agents against infectious disease. Front Immunol. 2014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2014.00079

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Janssen HL, Lim YS, Kim HJ, Sowah L, Tseng CH, Coffin CS, et al. Safety, pharmacodynamics, and antiviral activity of selgantolimod in viremic patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. JHEP Rep. 2024;6(2): 100975

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Agarwal K, Ahn SH, Elkhashab M, Lau AH, Gaggar A, Bulusu A, et al. Safety and efficacy of vesatolimod (GS-9620) in patients with chronic hepatitis B who are not currently on antiviral treatment. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(11):1331–1340

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Cargill T, Barnes E. Therapeutic vaccination for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Clin Exp Immunol. 2021;205(2):106–118

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ma H, Lim TH, Leerapun A, Weltman M, Jia J, Lim YS, et al. Therapeutic vaccine BRII-179 restores HBV-specific immune responses in patients with chronic HBV in a phase Ib/IIa study. JHEP Rep. 2021;3(6): 100361

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Tak WY, Chuang WL, Chen CY, Tseng KC, Lim YS, Lo GH, et al. Phase 1b/2a randomized study of heterologous ChAdOx1-HBV/MVA-HBV therapeutic vaccination (VTP-300) as monotherapy and combined with low-dose nivolumab in virally-suppressed patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2024;81:949–959

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Agarwal K, Yuen M-F, Wedemeyer H, Cloutier D, Shen L, Arizpe A, et al. Reduction in hepatitis B viral DNA and hepatitis B surface antigen following administration of a single dose of VIR-3434, an investigational neutralizing monoclonal antibody: first experience in a population with viremia. Hepatology. 2022;76:S303–S304

Google Scholar - Lee HW, Park JY, Hong T, Park MS, Ahn SH. Efficacy of lenvervimab, a recombinant human immunoglobulin, in treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(13):3043–5.e1

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zhao H, Shao X, Yu Y, Huang L, Amor NP, Guo K, et al. A therapeutic hepatitis B mRNA vaccine with strong immunogenicity and persistent virological suppression. NPJ Vaccines. 2024;9(1):22

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - De Pooter D, Pierson W, Pourshahian S, Dockx K, De Clerck B, Najera I, et al. mRNA therapeutic vaccine for hepatitis B demonstrates immunogenicity and efficacy in the AAV-HBV mouse model. Vaccines (Basel). 2024;12(3):237

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Liu S, Wang J, Li Y, Wang M, Du P, Zhang Z, et al. A multivalent mRNA therapeutic vaccine exhibits breakthroughs in immune tolerance and virological suppression of HBV by stably presenting the pre-S antigen on the cell membrane. Pharmaceutics. 2025;17(2):211

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang G, Cui Y, Xie Y, Mao Q, Xie Q, Gu Y, et al. ALT flares were linked to HBsAg reduction, seroclearance and seroconversion: Interim results from a phase IIb study in chronic hepatitis B patients with 24-week treatment of subcutaneous PDL1 Ab ASC22 (Envafolimab) plus nucleos (t) ide analogs. J Hepatol. 2022;77(S1):S70

Article Google Scholar - Wang G, Cui Y, Hu G, Fu L, Lu J, Chen Y, et al. HBsAg loss in chronic hepatitis B patients after 24-week treatment with subcutaneously administered PD-L1 antibody ASC22 (envafolimab): interim results from a phase IIb extension cohort. In: The Liver Meeting. Boston, US; 2023.

- Zhang X, Huang K, Zhu W, Zhang G, Chen J, Huang X, et al. Targeting inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) enhances intrahepatic antiviral immunity to clear hepatitis B virus infection in vivo. J Hepatol. 2020;73:S5–S6

Article Google Scholar - Fergusson JR, Wallace Z, Connolly MM, Woon AP, Suckling RJ, Hine DW, et al. Immune-mobilizing monoclonal T cell receptors mediate specific and rapid elimination of hepatitis B-infected cells. Hepatology. 2020;72(5):1528–1540

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hui RW, Mak LY, Fung J, Seto WK, Yuen MF. Prospect of emerging treatments for HBV functional cure. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2024;31:S165-181

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Mak LY, Wooddell CI, Lenz O, Schluep T, Hamilton J, Davis HL, et al. Long-term hepatitis B surface antigen response after finite treatment of ARC-520 or JNJ-3989. Gut. 2024;4:440–450

Google Scholar - Yuen MF, Asselah T, Jacobson IM, Brunetto MR, Janssen HLA, Takehara T, et al. Efficacy and safety of the siRNA JNJ-73763989 and the capsid assembly modulator JNJ-56136379 (bersacapavir) with nucleos(t)ide analogues for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection (REEF-1): a multicentre, double-blind, active-controlled, randomised, phase 2b trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(9):790–802

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Agarwal K, Buti M, van Bömmel F, Lampertico P, Janczewska E, Bourliere M, et al. JNJ-73763989 and bersacapavir treatment in nucleos(t)ide analogue-suppressed patients with chronic hepatitis B: REEF-2. J Hepatol. 2024;81:404–414

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Macquillan G, Elkhashab M, Antonov K, Valaydon Z, Davidson S, Fung SK, et al. Preliminary off- treatment responses following 48 weeks of vebicorvir, nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitor, and AB-729 combination in virologically suppressed patients with hepatitis B e antigen negative chronic hepatitis B: analysis from an open-label phase 2 study. Hepatology. 2023;78(S1):S47–S48

Google Scholar - Liu CJ, Avihingsanon A, Chuang WL, Leerapun A, Wong G, Yuen MF, et al. VTP-300 combined with low-dose nivolumab is associated with HBsAg loss in certain chronic hepatittis B participants with HBsAg less than 200 IU/ml: results from a phase 2B open-label study. In: The Liver Meeting 2024. San Diego, US; 2024.

- Wu D, Chen Y, Huang D, Yuan Z, Wu W, Yuan W, et al. Combination therapy with TLR7 agonist TQ-A3334 and anti-PD-L1 TQ-B2450 enhance HBsAg decline in virally-suppressed patients with chronic hepatitis B: OCEANcure05 study. Hepatology. 2024;80:S230–S231

Google Scholar - Gane E, Lim TH, Ngu JH, Tedesco D, Duan R, Pan D, et al. A phase 1B, open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacies of novel hepatitis B combination therapies in patients living with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2024;80:S258–S259

Google Scholar - Buti M, Heo J, Tanaka Y, Andreone P, Atsukawa M, Cabezas J, et al. Sequential Peg-IFN after bepirovirsen may reduce post-treatment relapse in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2025;82(2):222–234

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hou J-L, Zhang W, Xie Q, Hua R, Tang H, Amado L, et al. Xalnesiran with or without an immunomodulator in chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:2098–2109

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yuen MF, Lim YS, Yoon KT, Lim TH, Heo J, Tangkijvanich P, et al. VIR-2218 (elebsiran) plus pegylated interferon-alfa-2a in participants with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a phase 2 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;9(12):1121–1132

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jia J, Lin B, Hu P, Xie Q, Douglas M, Lv F, et al. Efficacy and safety of elebsiran (BRII-835) and pegylated interferon alfa-2A (Peg-IFNA) combination therapy vs PEG-IFNA in virologically suppressed participants with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection: preliminary results from an ongoing phase 2, randomized, open-label study (ENSURE). In: The Liver Meeting 2024. San Diego, US; 2024.

- Yuen MF, Heo J, Nahass R, Wong G, Burda T, Schiff E, et al. IM-PROVE I: Imdusiran in combination with short courses of pegylated interferon alfa-2A in virally suppressed, HBeAg-negative subjects with chronic HBV (CHB) infection leads to functional cure. In: The Liver Meeting 2024. San Diego, US; 2024.

- Kennedy PT, Fung S, Buti M, Yilmaz G, Chuang WL, Asselah T, et al. Efficacy and safety of siRNA JNJ-73763989, capsid assembly modulator-E (CAM-E) JNJ-56136379, and nucleos (t) ide analogs (NA) with pegylated interferon alpha-2a (PEGIFN-α2a) added in immune-tolerant patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection: interim results from the phase 2 REEF-IT study. Hepatology. 2023;78(S1):S568–S569

Google Scholar - Agarwal K, Yuen MF, Roberts S, Lo GH, Hsu CW, Chuang WL, et al. Imdusiran (AB-729) administered every 8 weeks for 24 weeks followed by the immunotherapeutic VTP-300 maintains lower HBV surface antigen levels in NA-suppressed CHB subjects than 24 weeks of imdusiran alone. J Hepatol. 2024;80(S1):S26–S27

Article Google Scholar - Wong G, Yuen MF, Kennedy P, Brown A, Chen CY, Lo GH, et al. Preliminary antiviral efficacy and safety of repeat dosing of imdusiran (AB-729) followed by VTP-300 with or withou nivolumab in virally-suppressed, non-cirrhotic subjects with chronic hepatitis B (CHB). In: The Liver Meeting 2024. San Diego, US; 2024.

- Bourgeois S, Buti M, Gane EJ, Agarwal K, Janczewska E, Hsu YC, et al. Efficacy, safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of JNJ-0535 following a reduction of viral antigen levels through administration of siRNA JNJ-3989 in patients with chronic HBeAg negative hepatitis B-interim data of the OSPREY study. J Hepatol. 2024;80:S79–S80

Article Google Scholar - Ji Y, Le Bert N, Lee A, Zhu C, Tan Y, Liu W, et al. Therapeutic vaccine (BRII-179) induced immune response associated with HBsAg reduction in a subset of chronic hepatitis B participants. J Hepatol. 2024;80:S36

Article Google Scholar - Doucette K, Jelev D, Kao JH, Amado L, Agarwal K, Asselah T, et al. Efficacy and safety of xalnesiran in combination with the checkpoint inhibitor PD-L1 LNA in virologically suppressed participants with chronic hepatitis B: Results from the PIRANGA phase 2, randomized, controlled, adaptive, open-label plateform study. In: The Liver Meeting 2024. San Diego, US; 2024.

- Asselah T, Fung SK, Akhan S, Chuang WL, Buti M, Brunetto M, et al. A phase 2 open-label study to evaluate safety, tolerability, efficacy, and pharmacodynamics of JNJ-73763989, nucleos (t)ide analogs, and a low-dose PD-1 inhibitor in patients with chronic hepatitis B-Interim results of the OCTOPUS-1 study. J Hepatol. 2024;80(S1):S27–S28

Article Google Scholar - Wong GL, Lim SG, Agarwal K, Avihingsanon A, Lim YS, Sowah L, et al. Results from a phase 2A, open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of novel combination therapies containing VIR-2218, selgantolimod, and nivolumab for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2024;80:S305

Google Scholar - Gane E, Agarwal K, Heo J, Jucov A, Lim YS, Streinu-Cercel A, et al. Tobevibart (VIR-3434) and elebsiran (VIR-2218) with or without pegylated interferon alfa-2A for the treatment of chronic HBV infection: end of treatment results after 48 weeks of therapy (MARCH study). In: The Liver Meeting 2024. San Diego, US; 2024.

- Paratala B, Park JJ, Ganchua SC, Gane E, Yuen MF, Lee ACH, et al. Inhibition of hepatitis B surface antigen in chronic hepatitis B subjects by RNA interference therapeutic AB-729 is accompanied by upregulation of HBV-specific T cell activation markers. J Hepatol. 2021;75:S761

Google Scholar - Matsumoto A, Nishiguchi S, Enomoto H, Tanaka Y, Shinkai N, Okuse C, et al. Pilot study of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and pegylated interferon-alpha 2a add-on therapy in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(10):977–989

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Seto WK, Wong DK, Fung J, Hung IF, Yuen JC, Tong T, et al. Serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) kinetics in hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hep Intl. 2012;7(1):119–126

Article Google Scholar - Leung RH, Hui RW, Mak LY, Mao X, Liu KS, Wong DK, et al. ALT to qHBsAg ratio predicts long-term HBsAg seroclearance after entecavir cessation in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2024;81(2):218–226

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mak LY, Cloherty G, Wong DK, Gersch J, Seto WK, Fung J, et al. HBV RNA profiles in patients with chronic hepatitis b under different disease phases and antiviral therapy. Hepatology. 2021;73(6):2167–2179

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Matsumoto A, Yatsuhashi H, Nagaoka S, Suzuki Y, Hosaka T, Tsuge M, et al. Factors associated with the effect of interferon-α sequential therapy in order to discontinue nucleoside/nucleotide analog treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol Res. 2015;45(12):1195–1202

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mak LY, Hui RW, Cheung KS, Fung J, Seto WK, Yuen MF. Advances in determining new treatments for hepatitis B infection by utilizing existing and novel biomarkers. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2023;18(4):401–416

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kan K, Wong DK, Hui RW, Seto WK, Yuen MF, Mak LY. Anti-HBc: a significant host predictor of spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B patients—a retrospective longitudinal study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23(1):348

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kan K, Wong DK, Hui RW, Seto WK, Yuen MF, Mak LY. Plasma interferon-gamma-inducible-protein 10 level as a predictive factor of spontaneous hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;39(1):202–209

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Murata K, Asano M, Matsumoto A, Sugiyama M, Nishida N, Tanaka E, et al. Induction of IFN-λ3 as an additional effect of nucleotide, not nucleoside, analogues: a new potential target for HBV infection. Gut. 2018;67(2):362–371

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Singh J, Salaun B, You S, Corson S, Paff M, Theodore D. Cell-mediated immunity analysis to assess the characteristics of immune response to bepirovirsen: Examples from the B-Clear study. J Hepatol. 2023;78:S1167–S1169

Article Google Scholar - Hogan T, Castaneda EG, Garcia EP, Barnard R, Ray A, Paff M, et al. High-dimensional analysis of flow cytometry data reveals differences in post-treatment frequencies of naive B cells, CD56dim natural killer cells, and terminally differentiated effector memory CD8+ T cells in responders versus nonresponders to bepirovirsen. J Hepatol. 2024;80:S807

Article Google Scholar

Funding

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Pok Fu Lam, Hong Kong

Rex Wan-Hin Hui, James Fung, Wai-Kay Seto, Man-Fung Yuen & Lung-Yi Mak - State Key Laboratory of Liver Research, The University of Hong Kong, Pok Fu Lam, Hong Kong

James Fung, Wai-Kay Seto, Man-Fung Yuen & Lung-Yi Mak

Authors

- Rex Wan-Hin Hui

- James Fung

- Wai-Kay Seto

- Man-Fung Yuen

- Lung-Yi Mak

Contributions

RWHH was involved in data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. JF and WKS were involved in critical revision of the manuscript. MFY and LYM were involved in study concept, critical revision of the manuscript, and overall study supervision. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence toMan-Fung Yuen or Lung-Yi Mak.

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

LY Mak received research funding from Gilead Sciences and Roche Diagnostics. MF Yuen is an advisory board member and/or received research funding from AbbVie, Arbutus Biopharma, Assembly Biosciences, Bristol Myer Squibb, Dicerna Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Clear B Therapeutics, Springbank Pharmaceuticals; and received research funding from Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, Fujirebio Incorporation and Sysmex Corporation. WK Seto received speaker’s fees from AstraZeneca and Echosens, is an advisory board member and received speaker’s fees of Abbott, received research funding from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer and Ribo Life Science, and is an advisory board member, received speaker’s fees and researching funding from Gilead Sciences. The remaining authors have no conflict of interests.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Human/animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hui, R.WH., Fung, J., Seto, WK. et al. Emerging therapies for HBsAg seroclearance: spotlight on novel combination strategies.Hepatol Int 19, 704–719 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-025-10828-0

- Received: 30 January 2025

- Accepted: 08 April 2025

- Published: 11 June 2025

- Version of record: 11 June 2025

- Issue date: August 2025

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-025-10828-0