Comparison of human genetic and sequence-based physical maps (original) (raw)

All nucleated human cells contain two homologous copies of each chromosome, except for the sex chromosomes in males. During the formation of the sperm and egg cells, the number of each chromosome is reduced to one so that fertilization restores the normal diploid number in the next generation. The process of chromosome reduction, meiosis, is usually accompanied by exchange or recombination of DNA between the homologous parental chromosomes. Genetic maps, which are based on meiotic recombination, order and estimate distances between DNA sequences that vary between parental homologues (polymorphisms). The primary unit of distance along the genetic maps is the centiMorgan (cM), which is equivalent to 1% recombination.

The genetic maps used in our analysis were based upon the genotyping of 8,031 short tandem repeat polymorphisms (STRPs) from Généthon, the University of Utah and the Cooperative Human Linkage Center in eight reference CEPH families5. Excluding the sex chromosomes, the maps cover about 4,250 cM in females and 2,730 cM in males. The genetic maps are relatively marker dense, with an average of 2–3 STRPs per cM, but are also relatively low resolution because only 184 meioses (92 in each sex) were analysed.

The physical maps used were all DNA sequence assemblies. For chromosomes 21 and 22, we used the finished, published sequences6,7. For the other 20 autosomes and for the X chromosome, we used the public draft sequence assemblies, 5 September 2000 version (http://genome.cse.ucsc.edu)4. As we required relatively long stretches of sequence, we used only sequence assemblies that were over 1.5 Mb long (between terminal STRPs), contained more than three STRPs and had a marker order that agreed with published genetic and radiation hybrid maps. The amount of sequence used from each chromosome is shown in Fig. 1. Some chromosomes had much better coverage than others. We analysed 253 sequence assemblies ranging in length up to 70 Mb and spanning a total of 1,806 Mb (roughly 58% of the portion of the genome that is not highly repetitive). By far the most common reason for rejecting sequence assemblies was insufficient length; only seven assemblies were rejected for incompatible marker order.

Figure 1: Sequence coverage for comparison of the genetic and physical maps.

The total length of sequence used in the analysis (open bars) and the approximate percentage of the euchromatic sequence length (solid bars) are shown for each chromosome.

Recombination rates varied greatly across the genome, from 0 to 8.8 cM Mb-1 (Table 1). Sex-average recombination rates (the average for males and females combined) did not vary as much as the sex-specific rates (for males and females considered separately) because male and female recombination rates at specific sites often differed substantially. We identified 19 recombination deserts up to 5 Mb in length with sex-average recombination rates below 0.3 cM Mb-1, and 12 recombination jungles up to 6 Mb in length with sex-average recombination rates greater than 3.0 cM Mb-1 (see Supplementary Information). Wide variation in recombination rates across chromosomes has been observed previously for humans8,9,10,11 and for other eukaryotic species12,13,14,15, and is clearly the rule rather than the exception.

Table 1 Distribution of recombination rates

In an effort to identify the basis of differences in recombination rates, we compared the rates to several marker and sequence parameters. These parameters included GC content, STRP informativeness, position of the marker relative to the centromeres and telomeres, density of runs of various short tandem repeats, especially (A)n, (AC)n, (AGAT)n, (AAN)n and (AAAN)n sequences, and the density of various interspersed repetitive elements, including Alu, L1, MIR (mammalian-wide interspersed repeats) and MER (medium reiterated repeats) sequences (Table 2).

Table 2 Correlations of recombination rates with sequence parameters

With one exception, we found only weak correlations between the parameters and recombination rates. As controls, we found the expected negative correlation between short interspersed nuclear element (SINE) and long interspersed nuclear element (LINE) densities16, and the positive correlation between SINE density and (A)n density. In agreement with ref. 17, we found no correlation between STRP heterozygosity and recombination rate, despite reports of positive correlation of nucleotide (sequence) diversity values with recombination rates18,19. However, STRP heterozygosities are probably much more dependent upon relatively high mutation rates than selection and are therefore likely to be poor measures of nucleotide diversity. Similarly, we found only weak correlation between (AC)n density (n ≥ 11 or 19) and recombination rates despite the report of such a correlation for chromosome 22 (ref. 20). GC content is of interest because the genome appears to be segmented into isochores of varying GC content and because GC content is strongly correlated with gene density21. We did confirm a positive relationship between recombination and GC content (ref. 22), but the correlation was weak. By far the strongest relationship detected was for the position of the markers along the metacentric chromosome arms in males. Male (but not female) recombination rates increased markedly near the telomeres.

Some important limitations apply to our comparison of human genetic and physical maps. First, the resolution of the genetic maps is modest, owing to the small number of meioses examined. This places relatively broad confidence intervals on the genetic map distances and similar broad confidence intervals on the recombination rates. Only sex-average recombination rates smaller than about 0.3 cM Mb-1 and greater than about 2.5 cM Mb-1 are statistically different from uniform recombination at the P = 0.05 significance level. Second, the draft sequences used in our analysis were often short, contained many gaps and still had some errors in marker order. When the finished sequences become available, additional recombination deserts and jungles, for example, will undoubtedly be discovered. Third, there is mounting evidence for at least modest individual and possibly population variation in recombination rates5,23,24. The genetic maps in our analysis were based on meiosis in only eight mothers and eight fathers, all or nearly all of European ancestry. Examination of a large sample of individuals and/or other populations might give different results. Finally, our analysis is only a long-range (megabase) analysis. We can reach no conclusions about recombination over short (kilobase) ranges. There is growing evidence for recombination hot spots no more than a few kilobases long13,25,26. Megabase-sized chromosomal segments may turn out to be comprised of regions with little or no recombination separated by short recombination hot spots. Perhaps the primary difference between recombination deserts and jungles lies in the density and strength of recombination hot spots.

Despite the limitations, there is strong evidence that our results are reliable first estimates of human recombination rates. Genetic maps based on 40 CEPH families show good agreement with the eight family maps (see, for example, ref. 8). Plots of the ratio of female to male recombination from the eight family data show maxima at the centromeres and minima at the telomeres for virtually all metacentric chromosomes5. The shapes produced by plotting centiMorgans against megabases obtained from the draft sequence assemblies for chromosomes 6 and 20 match closely those obtained using physical distances from restriction enzyme fingerprinting of overlapping genomic clones. Lengths of the draft sequence assemblies (17 July 2000 version) for chromosomes 21 and 22 matched the lengths of the finished sequences with only 0.1% error. And, probably most importantly, recombination deserts and jungles differ significantly in linkage disequilibrium (when two polymorphic alleles are not in random association).

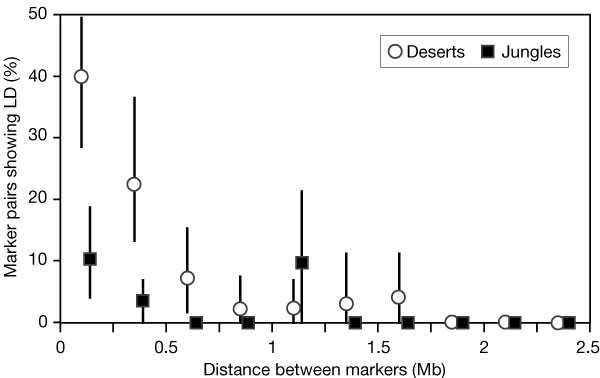

The decay of linkage disequilibrium is expected to be much slower in recombination-poor than in recombination-rich regions. We tested this hypothesis by comparing linkage disequilibrium among pairs of STRPs within the recombination deserts and jungles. Although the power to detect linkage disequilibrium in genotyping data from only eight families is low, it was still found to be much higher for close pairs of markers in the deserts than in the jungles (Fig. 2). For marker pairs less than 0.5 Mb apart, 32% of pairs in the deserts showed significant linkage disequilibrium, as compared with only 7% in the jungles (P = 0.001).

Figure 2: Linkage disequilibrium (LD) among pairs of STRPs within autosomal recombination deserts and jungles.

Deserts and jungles are listed in the Supplementary Information. Marker pairs were binned into 0.25-Mb spacing intervals.

In conclusion, our work shows that recombination rates vary greatly across the human genome, by at least two orders of magnitude. Linkage disequilibrium will generally extend over longer distances in regions with low recombination. Mapping genes responsible for traits and diseases by association studies will be easier and require a lower density of polymorphisms in regions of low recombination. Nucleotide and haplotype diversity will also probably parallel recombination rates. Although our baseline long-range recombination rates will be useful, they should be recalculated when the human genomic sequences are finished and as higher resolution genetic maps become available. In the more distant future, genotyping greater numbers of reference families at much higher polymorphism densities will lead to short-range maps of recombination hot spots.