A bouquet makes ends meet (original) (raw)

The term 'chromosomal bouquet' describes the positioning of one or both ends of the thread-like meiotic prophase chromosomes at a limited sector of the nuclear periphery (Fig. 1, Box 1) — just like the stems of flowers arranged in a bouquet. The chromosomal bouquet is ubiquitous among eukaryotes, and it forms during the extended prophase that precedes the two meiotic divisions, which are essential for gamete (or spore) development and sexual reproduction.

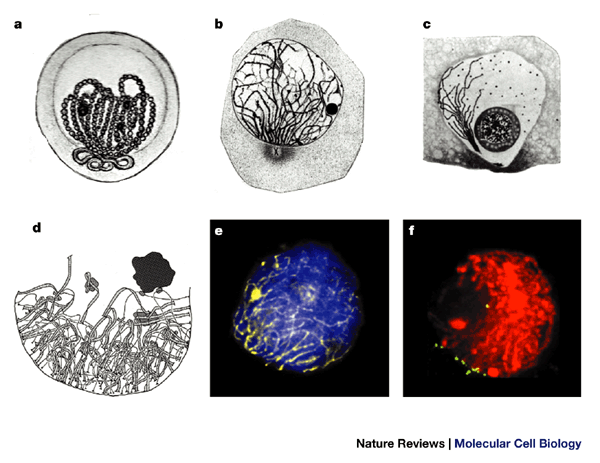

Figure 1: Chromosomal bouquets of different species.

a | Early drawing (1885) of a bouquet nucleus of Helix pomatia (reproduced from Ref. 63). b | Zygotene bouquet of Myxine glutinosa. Note the centrosome at the bouquet base (reproduced from Ref. 18). c | Bouquet arrangement during Coccid (intracellular parasite) prophase I (polarization involves only one telomere) . The large round sphere represents the nucleolus (reproduced from Ref. 21). d | Crowded early zygotene bouquet base in achiasmate meiosis of tetraploid Bombyx mori female (reproduced from Ref. 64, with permission from S. Rasmussen and P. Holm, The Carlsberg Laboratory). e | Late leptotene bouquet of a human spermatocyte. DNA is stained with DAPI (blue), axial cores by immunofluorescence with antibodies against SCP3 (yellow, false colour). The resemblance of the SCP3 staining and the chromosome structures depicted by the early cytologists (compare with a) suggests that these structures resemble axial elements or complete synaptonemal complexes. f | Projection of optical sections covering 5 μm near the centre of a DAPI-stained (red, false coloured) three-dimensionally preserved maize bouquet nucleus after telomere fluorescence in situ hybridization (green signals). Telomeres are grouped at the lower left of this nucleus (reproduced with permission from Ref. 65 © (1997) The Rockefeller University Press).

The bouquet arrangement was first described during the late 1800s (TIMELINE), when chromosomes had just been discovered and awaited recognition as persisting structures that underlie the laws of inheritance. Chromosomes, at that time, were considered to undergo cycles of dissolution and reformation1 (direkte Zelltheilung; 'direct cell division'), until the technically gifted Walther Flemming2,3 unveiled the complete sequence of nuclear metamorphosis during the late 1870s. Although Flemming at first failed to recognize the significance of what he described as indirekte Zelltheilung ('indirect cell division')2, his report stimulated Wilhelm Roux to reason that indirect cell division contributes to the equal distribution of the nuclear 'quantities and qualities'4 — and not just quantity, according to the direct division of the nucleus assumed by most of his peers.

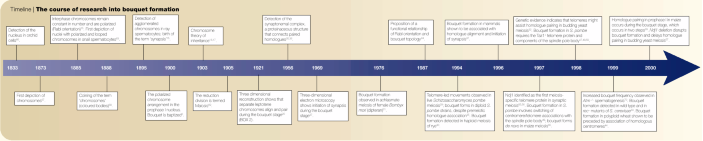

Timeline | The course of research into bouquet formation

The permanence of somatic chromosomes and their orientation throughout the cell cycle was first demonstrated in 1885 by Carl Rabl. By observing living salamander cells Rabl showed that, after anaphase, chromosomes decondense into an interphase nucleus, only to reappear at the ensuing prophase in the same anaphase-like arrangement, with the centromeres still pointing towards the centrosome5. This is known as the 'Rabl orientation', and has been observed in somatic tissues of some animals and in plant. It contrasts with the unique 'bouquet' arrangement of chromosomes in prophase of the first meiotic division, where telomeres are bundled at the nuclear envelope facing the centrosome (Fig. 1). This arrangement owes its flowery name to the imagination of Gustav Eisen who, in 1900, was investigating salamander meiosis6 (TIMELINE). But the discovery of how this peculiar arrangement relates to the reduction of chromosome number (which creates haploid gametes or spores) had to await the meticulous study of chromosome behaviour during flatworm meiosis, done by József Gelei (Box 2) a little more than a decade later.

In this article, I describe the circumstances and scientific atmosphere in which the bouquet was discovered, over 100 years ago, and align the early achievements with the most recent advances. Additional aspects of bouquet formation have been reviewed elsewhere (for examples, see Refs 7–10).

The concept of a reduction division

During the late nineteenth century, scientists realized that, to maintain a constant diploid number of chromosomes in most somatic cells from individuals of the same species, a mechanism was needed that could compensate for the genome doubling at fertilization11. In 1887, August Weismann, although not fully aware of the mechanism involved, put forward the concept of a reductional division ('Reduktionstheilung')12, which halves the diploid chromosome number in the germ cells.

On the basis of this concept, the zoologist Theodor Boveri suggested, in 1892, that homologous chromosomes (homologues) should pair up (Konjugation) ahead of the reductional division13. Such pairing was detected shortly after by Johannes Rückert, who studied oogenesis in copepods — during the first meiotic division, the chromosomes of Cyclops appeared in pairs, the number of which was half the diploid number14. Subsequently, in 1895, John E. S. Moore observed an entangled mass of thread chromosomes, which sometimes appeared polarized towards one side of the nucleus during the prophase of meiosis I in sharks and rays. He called this synapsis 15 — a term that is still used today to denote intimate meiotic chromosome pairing. When conjugation and reductional segregation of homologues during meiosis were found to match the segregation patterns of genes described by Gregor Mendel in 1865, these findings were soon amalgamated in the chromosome theory of heredity16,17 (TIMELINE).

Polarization and homologue alignment

At the turn of the twentieth century, scientists focused their interest on how chromosomes behave during metaphase I and II of gametogenesis. One debate at this time was whether homologous chromosomes associate end-to-end or whether they pair up along their lengths. Cytological studies in various species disclosed the elongation and lengthwise conjugation of homologues, but the conditions required for this conjugation remained unclear because chromosomes were hardly traceable or were already associated in pairs when they became discernible in a bouquet arrangement6,18 (Fig. 1a,b). In 1904, Theodor Boveri put forward a first hypothesis of the significance of the peculiar chromosome arrangement seen at prophase i . In reference to Moore's synapsis15, he wrote19, “ ... I consider it conceivable that this remarkable agglomeration [of meiotic chromosomes] represents the mutual searching of the homologous chromosomes ... ”.

At this stage, the Hungarian cytologist József Gelei (Box 2) began to unravel the sequence of events that lead to the side-by-side pairing of homologues20. His studies benefited from his technical skill and the favourable cytology of the flatworm Dendrocoelum lacteum, which has only seven pairs of morphologically distinct homologues (2n = 14). By carefully controlling fixation, Gelei managed to preserve the fragile leptotene chromosome arrangement, including the bouquet topology (he applied a dilute formaldehyde–osmium tetroxide fixative, instead of Flemming's strong fix (glacial-acetic-acid–haematoxilin), which easily precipitates early prophase chromosomes into a dense lump (later called a synizetic knot). This circumstance was confirmed by Karl Belar who, by photographing salamander testes tissue and Lily anther tissue sections live and after fixation, showed that the knotted morphology results from a tendency of leptotene/ zygotene chromosomes to clot upon acidic fixation and squashing, whereas post-zygotene chromosomes were less sensitive to fixation variables21.

Gelei's well-preserved flatworm material allowed him to show that, at the onset of the first meiotic prophase, D. lacteum chromosomes rearrange into continuous leptotene strands20. By reconstructing the three-dimensional course of the extraordinarily clear prophase chromosomes from consecutive drawings of focal planes, he revealed that separated leptotene chromosomes have their ends scattered over the nuclear periphery (Fig. 2a). Later, at leptotene, the chromosome ends — called 'telomeres' by Hermann Muller22 in 1938 — had congregated at a limited sector of the nuclear envelope (bouquet topology; Fig. 2b), leading to what appeared as an alignment of hook-shaped chromosomes when viewed at a distance20. Still, most homologues in the leptotene bouquet were well separated (Fig. 3a,b).

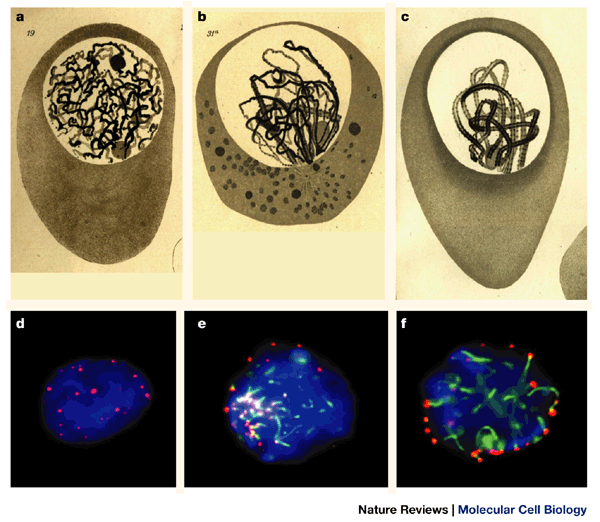

Figure 2: Dynamics of the bouquet stage in prophase I of flatworm (a–c) and mouse (d–f).

a | At leptotene, flatworm chromosomes are discernible as long thin threads with their ends at the nuclear periphery. Note the two separated nucleoli (round spheres). b | Early zygotene bouquet with synapsis in progress (thick threads) near the bouquet base, opposite the cytoplasmic centrosome. There is one nucleolus present. c | Pachytene bouquet. Paired homologues are still polarized (a–c are reproduced from Ref. 20). d | Focal mid-section of a premeiotic nucleus (spermatogonium) of the mouse, containing telomeres (red) in its interior. e | Focal plane at the top of an early zygotene bouquet nucleus, showing short stretches of synaptonemal complexes and axial elements (green, immunofluorescence against SCP3) extending from the clustered telomeres. f | Focal plane at the equator of a pachytene nucleus. Telomeres are scattered over the nuclear periphery whereas synaptonemal complexes meander through the nuclear lumen. DNA is stained with DAPI (blue). Chromosome polarization is no longer apparent37.

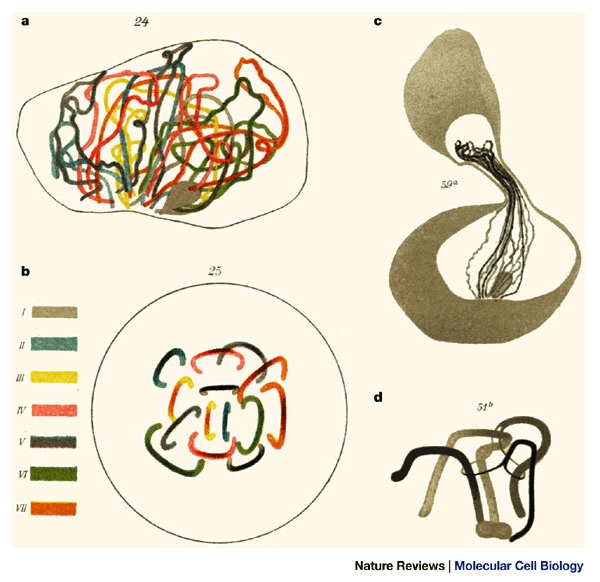

Figure 3: Chromosome topology in the flatworm bouquet.

a | Reconstructed leptotene bouquet of Dendrocoelum lacteum with colour-coded homologue positions as derived from three-dimensional reconstructions. b | Polar projection of the same nucleus in a (opposite to the bouquet base) showing separate homologue positions. Gelei noted that leptotene bouquets seldom had more than one homologue pair in alignment. c | Bouquet spermatocyte with firmly attached telomeres. The chromosomes have been stretched by micromanipulation. d | Interlocking of three chromosome bivalents. Two bivalents are trapped between the unpaired axial elements of the third bivalent (reproduced from Ref. 20).

Gelei concluded that bouquet formation (congregation of telomeres ) confers a parallel alignment of homologues and still allows a substantial amount of movement, which probably involves the cytoskeleton (the aggregation of the chromosome ends always occurred near the centrosome at the cytoplasmic face of the bouquet base; Figs 1a,b;2b)6,18,20. This topology distinguishes the bouquet from the previously described Rabl orientation, in which the centrosome faces the centromeres clustered during the preceding anaphase5. Gelei also pioneered micromanipulation experiments (Fig. 3c), which revealed a firm attachment of chromosome ends to the nuclear envelope — he failed to pull the telomeres out of the bouquet base20.

During the next two decades, the bouquet arrangement was recognized to be a universal motif of the first meiotic prophase in species from different kingdoms. The length of time this arrangement persists is species-specific21,23 (Fig. 2). It was assumed that bouquet formation conferred an approximate alignment of homologues20,24, but the significance of bouquet formation for the chromosome pairing process remained difficult to test8 until molecular genetic tools provided ways to tackle the problem experimentally.

Bouquet formation and recombination

During the 1950s, a tripartite zipper-like protein ribbon — termed the synaptonemal complex (TIMELINE) — was found to connect homologues along their length at pachytene 25,26. Three-dimensional electron-microscopy reconstruction of plant, insect and vertebrate meiocytes revealed that homologues are stitched together by the synaptonemal complex during the bouquet stage7,27. The high-resolution electron microscopy studies also confirmed Gelei's finding of a firm attachment of prophase telomeres to the nuclear envelope7,27, and revealed electron-dense nodules (recombination nodules). These nodules were associated with the synaptonemal complex and, by their correspondence in number and distribution with chiasmata , they were invoked in recombination28.

Ultrastructural and genetic analyses have since shown that bouquet formation is independent of both synapsis and recombination. A bouquet forms during asynaptic meiosis of fission yeast29, of haploid rye30, and during achiasmate (non-recombinant) female meiosis of the dipteran Bombyx mori31, as well as in recombination-deficient mutants of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae32,33 (which also fail to form a mature synaptonemal complex9). But why should this be?

Assuming that the benefit of meiotic telomere clustering is the instigation and temporal stabilization of unstable chromosome interactions, this clustering should be dispensable when growing synapsis has fortified such interactions. In agreement with this idea, bouquet topology dissolves during zygotene/early pachytene in most organisms that have synaptic meiosis34, whereas it is maintained during the entire asynaptic prophase I of fission yeast29,35. Moreover, perturbation of synapsis (by interfering with meiotic recombination) has been shown to prolong the bouquet stage in mutants of budding yeast and mouse33,36. In the mouse, the short bouquet duration37 (Fig. 2) is indirectly extended by disruption of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (Atm) kinase36, which is a central part of the machinery that senses DNA damage, repairs double-stranded DNA breaks during meiosis, and mediates aspects of telomere metabolism38. The findings in mouse36 and yeast mutants33 do not support a direct link between recombination and bouquet formation. So, a prevalence of bouquet spermatocytes in recombination mutants of mouse and yeast might result from synaptic problems in these mutants.

Chromosome topology and bouquets

In flatworm zygotene nuclei, Gelei observed the entrapment of chromosome cores between those of other homologue pairs20 (Fig. 3d). These findings were later extended at the electron microscopic level in several species, including humans7. Gelei's (and later) observations suggested that movements of U-shaped bouquet chromosomes might facilitate revolving of chromosomes around each other — this might reduce the frequency of entanglements before synapsis. However, once interlocking has occurred between cores of otherwise synapsed bivalents, it is evident that such entrapment cannot be resolved by bouquet formation, but that it requires breakage and rejoining of one chromosome core7. Bouquet topology has also been considered to facilitate pairing of rearranged chromosomes; for example, a pair of homologues in which one carries an inverted segment, or a Robertsonian translocation heterozygote37. In agreement, genetic evidence indicates that the ability of a heavily rearranged pair of yeast homologues to undergo limited pairing requires telomeres32.

During the late twentieth century, refined molecular genetic technology led to the isolation of numerous meiotic mutants and to the development of protein markers and molecular probes for meiotic prophase of fungi, plants and animals. In combination with high-resolution fluorescence imaging of three-dimensionally preserved nuclei34, application of these tools showed that pre-leptotene chromosomes are separated in most diploid species from different kingdoms, and that homologues align and start to pair intimately during the bouquet stage37,39. Even species with premeiotic homologue association or a strong Rabl orientation were found to establish a bouquet topology24,35,39.

As first depicted in flatworm meiotic prophase20, bouquet formation in diploid plants and animals was found to be a two-step process, involving the dispersed attachment of telomeres to the nuclear envelope and their subsequent movements towards the cluster site7,37,39 which, in animals, is defined by the centrosome (Figs 1a,2b ) and in yeast by its equivalent, the spindle pole body (SPB)33. In plants, which lack a localized microtubule-organizing centre, bouquet formation coincides with polarization of the entire cell40. Polyploid plant species were found to maintain a Rabl orientation which, together with bouquet formation, might facilitate homosynapsis24,41. Finally, in all species investigated so far, the minimal time window of bouquet formation has been identified as the leptotene–zygotene transition10,34. Below I discuss some of the most recent advances in understanding meiotic telomere clustering. These have largely come from yeast, owing to the ease with which meiotic mutants can be obtained and analysed in synchronized cultures.

Telomere clustering

Telomeres have been found to be essential for chromosome stability. They regulate the replicative lifespan of somatic cells22,42, and loss of telomeric DNA repeats is incompatible with meiosis43. The protein components of mitotic telomeres also localize to meiotic telomeres44,45 and, in mammalian meiosis, these include TRF1 and TRF2 (which bind duplex telomere repeats). These share homology with the Taz1+ telomere protein of Schizosaccharomyces pombe46, which has been found to be essential for bouquet formation47,48.

In S. pombe, telomere clustering occurs in response to mating pheromone49 and is dependent on the integrity of the SPB50. Mutation of the SPB or disruption of cytoplasmic dynein51 impairs bouquet formation and nuclear motility, respectively, leading to reduced levels of homologue pairing and recombination50,51. These observations are consistent with a role of the cytoskeleton in bouquet formation, as proposed by Gelei20.

By analogy to the situation in S. pombe, microtubule-destabilizing drugs have been shown to interfere with nuclear motility and synapsis in plants and animals52,53. So far, it is not known whether such drugs directly affect bouquet formation. In S. cerevisiae, deletion of the microtubule-associated motor KAR3 (kinesin-like nuclear fusion protein 3) has been observed to impair synapsis and recombination54. However, analysis of haploid yeast meiosis revealed bouquet formation in kar3Δ cells (E. Trelles-Sticken, J. Loidl and H.S., unpublished data), which does not support a role for KAR3 in bouquet formation.

Disrupting bouquets: synaptic meiosis

In 1997, NDJ1, a meiosis-specific telomere protein from S. cerevisiae, was found to be required for proper distribution of crossovers, homologue disjunction and the integrity of the telomere complex55,56. NDJ1 is the first protein shown to be required for bouquet formation in an organism that undergoes synaptic meiosis57. An NDJ1 mutation abrogates meiosis-specific telomere distribution56,57. Furthermore, fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis showed that, in addition to bouquet disruption, NDJ1 mutants have a considerable delay in homologue pairing (but ultimately they succeed)57. Notably, physically smaller chromosomes suffer from the absence of bouquet formation, presumably because they will have less opportunity for chance encounters with their homologues. Thus, the phenotype of this bouquet-defective mutant supports the hypothesis that the catalytic activity of bouquet formation promotes the physical proximity of pairing-competent leptotene chromosomes24,32 (Box 1).

It now seems likely that NDJ1 is involved in tethering telomeres to the meiotic nuclear envelope55,57. Interestingly, the nuclear envelope of frog oocytes contains a 70-kDa protein that is related to the mammalian TRF2 telomere protein and might be involved in telomere attachment at the nuclear envelope58. In this respect, it is interesting that the predicted NDJ1 protein has a carBoxy-terminal myristoylation site (H.S. and E. Trelles-Sticken, unpublished data) — a modification that was recently shown to target the meiosis-specific lamin C2 to the meiotic nuclear envelope of rat spermatocytes59. During mitotic interphase, yeast telomeres are tethered to nuclear pores through the Ku protein and the nucleoplasmic pore extensions MLP1 and MLP2 (which are TPR homologues)60. During human prophase I, however, nuclear pores and telomeres redistribute in spatially distinct sectors of the nuclear envelope45, which does not support a role for nuclear pores and associated proteins in the attachment of meiotic telomeres.

Conclusions

Over a century has passed since the first depiction of the chromosomal bouquet. Despite its ubiquitous occurrence, predictions about the role of the bouquet for homologue pairing remained difficult to test directly, as appropriate methods and mutants were largely absent during most of the previous century. Recently this has changed, and the refined tools of molecular genetics and cytology now allow us to track chromosome behaviour in fixed and live prophase nuclei of various species. Analysis of bouquet formation and dissolution using suitable mutants of unicellular and multicellular eukaryotes, molecular markers, fluorescent in situ hybridization and green fluorescent protein technology should help to answer questions about the factors involved in meiotic telomere/nuclear membrane attachment, the determinants of meiotic chromatin organization and the role of dynamics of the cytoskeleton in the generation of meiotic chromosome topology and telomere behaviour. These efforts shall further brighten the stage where (fri)ends meet.