PP2A regulatory subunit Bα controls endothelial contractility and vessel lumen integrity via regulation of HDAC7 (original) (raw)

Abstract

To supply tissues with nutrients and oxygen, the cardiovascular system forms a seamless, hierarchically branched, network of lumenized tubes. Here, we show that maintenance of patent vessel lumens requires the Bα regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A). Deficiency of Bα in zebrafish precludes vascular lumen stabilization resulting in perfusion defects. Similarly, inactivation of PP2A‐Bα in cultured ECs induces tubulogenesis failure due to alteration of cytoskeleton dynamics, actomyosin contractility and maturation of cell–extracellular matrix (ECM) contacts. Mechanistically, we show that PP2A‐Bα controls the activity of HDAC7, an essential transcriptional regulator of vascular stability. In the absence of PP2A‐Bα, transcriptional repression by HDAC7 is abrogated leading to enhanced expression of the cytoskeleton adaptor protein ArgBP2. ArgBP2 hyperactivates RhoA causing inadequate rearrangements of the EC actomyosin cytoskeleton. This study unravels the first specific role for a PP2A holoenzyme in development: the PP2A‐Bα/HDAC7/ArgBP2 axis maintains vascular lumens by balancing endothelial cytoskeletal dynamics and cell–matrix adhesion.

The protein phosphatase 2A holoenzyme including the Bα regulatory subunit is shown for the first time to play a specific role during development. PP2A‐Bα regulates HDAC7, which in turn modulates endothelial cell cytoskeleton dynamics through ArgBP2 to stabilize blood vessel lumens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Angiogenesis, the emergence of new blood vessels from a pre‐existing vascular network, is a decisive process in development and tissue homeostasis of vertebrates (Potente et al, 2011). During angiogenesis, ECs lining the interior of all blood vessels undergo a dynamic sequence of cellular processes, including activation, sprouting, degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM), migration and proliferation (Adams and Alitalo, 2007). Ultimately, tubulogenesis, the process of lumen formation, ensures the establishment of a network of interconnected tubules that permits the transport of fluids, nutrients, circulating cells, hormones and gases to almost all tissues throughout the body (Iruela‐Arispe and Davis, 2009; Xu and Cleaver, 2011). During the past two decades, research in vascular biology has made a significant progress in understanding the cellular and molecular events that control individual steps of sprouting angiogenesis (Geudens and Gerhardt, 2011). Despite some recent seminal studies, the mechanisms that govern the step of lumenization (how blood vessels generate and stabilize lumens) remain poorly understood (Iruela‐Arispe and Davis, 2009; Strilic et al, 2009; Xu and Cleaver, 2011).

Reversible protein phosphorylation is a fundamental post‐translational regulatory mechanism that alters the biological activity of a myriad of signalling and structural proteins. Although protein kinases have long been considered as the undisputed effectors in cellular processes that are controlled by protein phosphorylation, the counterbalancing phosphatases are now unanimously acknowledged as equally important to accomplish coordinated regulation of cellular functions (Virshup and Shenolikar, 2009). Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is an abundant cellular serine/threonine phosphatase that has been implicated in the regulation of numerous signalling pathways (Janssens and Goris, 2001). Substrate‐specific activity of PP2A is achieved through intricate control mechanisms, with holoenzyme composition being the most decisive factor in PP2A regulation. PP2A holoenzymes are built around a core enzyme comprising the scaffold A and catalytic C subunits, onto which a third, variable B regulatory subunit is docked. The B‐type subunit is crucial for discriminating between each PP2A holoenzyme, as it dictates substrate specificity, subcellular localization and catalytic activity of the heterotrimer (Sents et al, 2012). Despite the well‐recognized importance of PP2A, very few cellular functions, including intracellular signalling (Bengtsson et al, 2009; Yan et al, 2010; Rodgers et al, 2011), cell division (Yan et al, 2000; Chan and Amon, 2009; Jayadeva et al, 2010; Manchado et al, 2010; Brownlee et al, 2011; Foley et al, 2011; Isoda et al, 2011; Song et al, 2011; Wang et al, 2011) and apoptosis (Merrill et al, 2012; Yan et al, 2012), have been undisputedly attributed to specific PP2A holoenzymes, as defined by their regulatory subunit. To date, the putative roles of PP2A regulatory subunits in development remain largely undisclosed.

While earlier findings suggested a general involvement of PP2A activity in angiogenesis signalling, the role of specific PP2A holoenzymes in the angiogenic process is unknown (Gabel et al, 1999; Schmidt et al, 2006; Guenebeaud et al, 2010; Le Guelte et al, 2012). Here, we explore the role of PP2A regulatory subunits in angiogenesis and provide evidence that the regulatory subunit Bα (B55α/PR55α) of PP2A is necessary to maintain endothelial tubular networks in vitro and in vivo. Molecular analysis of the underlying mechanism revealed that PP2A‐Bα dephosphorylates histone deacetylase 7 (HDAC7) to control its function as a transcriptional repressor. A lack of PP2A‐Bα inhibits HDAC7‐mediated transcriptional repression and leads to aberrant expression of the cytoskeleton regulator sorbin and SH3 domain‐containing protein 2, Sorbs2/ArgBP2. We show that overexpression of ArgBP2 promotes hyperactivation of RhoA/ROCK signalling thereby preventing adequate endothelial actomyosin cytoskeleton rearrangements, which are necessary to maintain vascular lumen integrity.

Results

PP2A regulatory subunit Bα is required for endothelial tube formation

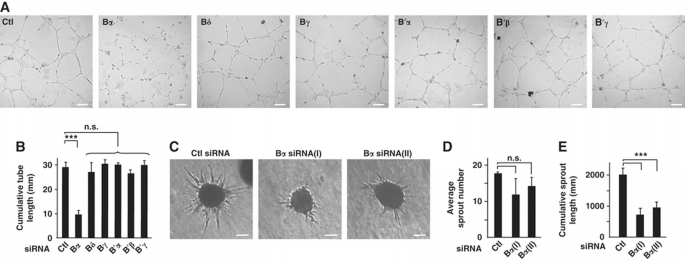

To explore the potential role of specific PP2A holoenzymes in angiogenesis, we designed a series of siRNA oligonucleotides that specifically suppress the expression of each PP2A B (Bα, ‐β, ‐δ, ‐γ) and B′ (B′α, ‐β, ‐δ, ‐γ, ‐ε) regulatory subunits (Supplementary Figure S1A). Knockdown of endothelial Bβ, B′δ and B′ε isoforms resulted in excessive cell death, making it impossible to further assess the role of these regulatory subunits in endothelial angiogenic behaviour (Supplementary Figure S1B and C). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) deficient in the α, δ, and γ B and α, β, and γ B′ PP2A regulatory subunits (Supplementary Figure S1D) were further assessed for their ability to form capillary‐like networks in vitro. Among these, silencing of Bα was uniquely associated with impaired formation of a continuous vascular‐like network (Figure 1A and B). Time‐lapse microscopy revealed that PP2A‐Bα‐deficient ECs were able to form branched networks. However, Bα KD ECs were unable to maintain these networks, as branches were highly unstable and hypocellular, leading to a rapid collapse of the network (Supplementary Movie 1). This inability of PP2A‐Bα‐depleted cells to stabilize capillary‐like structures could not be explained by excessive cell death since treatment with a pan‐caspase inhibitor (ZVAD) did not prevent Bα KD‐associated vascular network collapse (Supplementary Figure S1F–H).

Figure 1

PP2A regulatory subunit Bα is required for endothelial tube formation in vitro. (A) HUVECs were transfected with siRNA against indicated proteins and assessed in a tubulogenesis assay on a gelled basement membrane matrix (Matrigel). Micrographs of one representative experiment out of five are shown. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (B) Cumulative length of capillary‐like structures as obtained in (A) was measured by light microscopy in five different fields. (C) HUVECs transfected with two different siRNAs targeted against PP2A‐Bα, or with the control siRNA, were used in a spheroid‐based angiogenesis assay. Micrographs of one representative experiment out of three are shown. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (D, E) Average sprout number (D) and cumulative length of all sprouts (E) extending from spheroids (_n_=36) generated in three independent experiments described in (C) were calculated. Data are mean±s.d.; Student's _t_‐test: ***P<0.001, n.s., non‐statistically significant.

Importantly, an siRNA targeting a different sequence of Bα similarly reduced the ability of HUVECs to maintain capillary‐like structures in vitro (Supplementary Figure S1I). Bα‐deficient ECs were further characterized in a three‐dimensional sprouting assay. Inhibition of Bα did not significantly affect the average number of sprouts per spheroid, but severely impaired sprout propagation (Figure 1C–E). Since siRNA‐mediated inhibition of Bα did not affect the expression of other B or B′ isoforms (Supplementary Figure S1A and D), these results collectively indicate that PP2A‐Bα is specifically required for angiogenic properties of ECs.

PP2A regulatory subunit Bα controls vascular lumen integrity in zebrafish

To investigate the angiogenic functions of PP2A‐Bα in vivo, we used the zebrafish model in which the formation and patterning of the vasculature can be dynamically monitored (Isogai et al, 2003). BLAST homology searches against the NCBI protein database and phylogenetic comparison with PP2A regulatory subunits from human, rat and mouse species identified two PP2A‐Bα orthologues in danio rerio, zB_α_a (NP_956070.1) and zB_α_b (XP_687103.5). Both genes displayed wide‐spread expression in the developing embryos, with prominent expression throughout the CNS. Lower levels of expression of zB_α_a and zB_α_b were detected in the dorsal aorta (DA), posterior cardinal vein (PCV) as well as in intersomitic vessels (ISVs) (Supplementary Figure S2A).

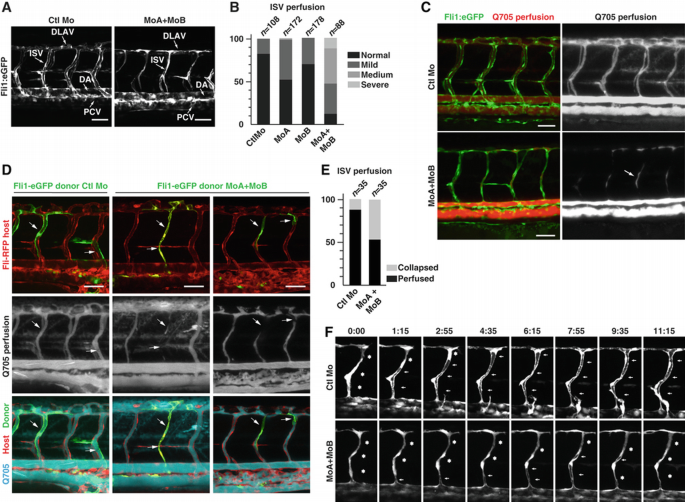

To analyse the functions of zB_α_a and zB_α_b during zebrafish blood vessel development, we used two splice‐blocking morpholinos (MoA and MoB) targeting the exon 1/intron 1 boundary of zB_α_a and zB_α_b, respectively. RT–PCR analysis confirmed that the morpholinos efficiently and specifically blocked splicing of the corresponding mRNAs (Supplementary Figure S2B) without affecting the overall embryo morphology (Supplementary Figure S2C). To analyse blood vessel development, MoA and MoB were injected alone or in combination into zebrafish embryos expressing the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) under the control of the endothelial promoter fli‐1, Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1. Time‐lapse analysis during the first 30 h of development revealed no differences in the morphogenesis and patterning of ISVs between control Mo and the MoA/MoB‐injected embryos. However, at later stages of development, vascular defects appeared specifically in the zB_α_a/b morphants in which thinner ISVs and DLAVs were frequently observed (Figure 2A). These vessels lacked an apparent lumen and perfusion of the trunk vasculature was consequently impaired. These findings were further confirmed by using the vascular and haematopoietic double‐transgenic reporter line Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1;Tg(gata1a:dsRed)sd2, which allows observation of blood circulation in real time. Recording of blood flow in MoA/MoB‐injected embryos at 68 hpf revealed abnormal trunk circulation with blunted flow in a large proportion of ISVs and a consequent reduction in axial circulation (Supplementary Movie 2; Supplementary Figure S2D). The majority of the single zB_α_a or zB_α_b morphants displayed fully lumenized ISVs and showed no or minor circulation abnormalities, indicating a functional redundancy between the two genes in ECs (Figure 2B). In contrast, zB_α_a/zB_α_b double morphants exhibited narrowed or closed lumens in the majority of the ISVs. These observations were substantiated by microangiographies at 55 hpf in control embryos and zB_α_a/b morphants as well as by combinatorial injection of two alternative morpholinos against zB_α_a and zB_α_b (MoA2 and MoB2), which gave similar results (Figure 2C; Supplementary Figure S2E). Notably, the lumen of the DA and caudal vein was not affected by combined zB_α_a and zB_α_b deficiency. Defective lumenization was not a reflection of an insufficient number of ECs constituting the ISVs in zB_α_a/b double morphant embryos, as counting the number of ECs in morphant embryos from a transgenic Tg(fli1a:nEGFP)y7 line showed only a minor reduction in the average number of ECs per ISV compared with control (4.53±1.01 for the control (_N_=536 ISVs) and 3.86±0.91 for the Bα morphant (_N_=584), _P_=n.s.). Rescue experiments further confirmed the specificity of the vascular defects associated with inhibition of PP2A‐Bα. Indeed, co‐injection of mRNA coding for human Bα with the MoA/B combination compensated for lack of zB_α_a/b and efficiently reduced the severity of the phenotype restoring normal lumen and blood circulation in the majority of the ISVs (Supplementary Figure S2F).

Figure 2

PP2A regulatory subunit Bα controls vascular lumen integrity in zebrafish. (A) Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1 embryos were injected with control morpholino (CTL Mo) or with the combination of morpholinos targeting both zebrafish Bα orthologues (MoA+MoB). Confocal pictures of the trunk vasculature were taken at 55 hpf. Whereas Ctl embryos show normal ISVs and DLAVs with open lumen, these vessels appear thin and collapsed in the morphant embryos. Scale bars represent 50 μm. DA, dorsal aorta; PCV, posterior cardinal vein; ISV, intersegmental vessel; DLAV, dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessels. (B) Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1 embryos were injected with control Mo, MoA (MoA), MoB (MoB) or MoA and MoB (MoA+MoB). Vascular defects were classified into four categories: normal, mild, medium or severe depending on whether circulation was detected in all, the majority, a minority or none of the ISVs, respectively. For each condition of injection, the distribution of each phenotype among the population was quantified (_n_=number of embryos; Pearson's chi‐squared test: P<0.001). (C) Microangiographies of control and MoA/MoB‐injected Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1 embryos at 55 hpf: confocal pictures showing normal quantum dots perfusion (red) in ISVs (green) of Ctl embryos, whereas perfusion is blocked in most of the ISVs of morphant embryos. Arrow indicates trapped perfusion dye in the mid‐portion of an ISV indicating partial collapse of a previously open lumen. Scale bars represent 50 μm. (D) Tg(fli1a:RFP) embryos were transplanted with cells from control or MoA/MoB‐injected Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1 embryos. At 2 dpf, angiography was performed with quantum dots and confocal pictures were taken in order to monitor perfusion (blue) in ISVs having incorporated transplanted cells from the donor (green) and/or the host (red). Scale bars represent 50 μm. (E) Quantification of the transplantation experiments from (D) was performed by evaluating the perfusion of ISVs containing transplanted cells from control versus morphant embryos. The graph shows the percentage of ISVs that are collapsed and perfused (_n_=number of ISVs; Pearson's chi‐squared test: P<0.001). (F) Formation of lumen in control and MoA/MoB Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1 embryos is illustrated by still images from Supplementary Movies 3 and 4. Asterisks indicate closed lumen whereas arrows indicate open lumen.

To test whether the tubulogenesis phenotype associated with knockdown of PP2A‐Bα is cell autonomous, we performed cell transplantation experiments. Donor cells from control Mo or MoA/B‐injected Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1 embryos were transplanted into Tg(fli1a:RFP) embryos at oblong/sphere stage. Transplanted ECs from control Mo‐injected embryos formed normal ISVs with a stable and functional lumen (Figure 2D and E). ECs derived from zB_α_a/b morphant embryos efficiently integrated into the wild‐type host vasculature with no obvious bias for position in the emerging vascular branches. However, ISVs that were completely or partially formed by morphant cells often failed to maintain a properly shaped and functional lumen at 54 hpf (Figure 2D and E). In contrast, neighbouring ISVs comprised exclusively of wild‐type cells sustained effective perfusion, indicating that PP2A‐Bα functions in an EC‐autonomous manner during sprout lumenization in ISVs.

During microangiography experiments, we observed that zB_α_a/b morphant ISVs often contained quantum dots only in their mid‐portion (Figure 2C, arrow), suggesting that a functional lumen had formed and collapsed after the tracer was injected into the circulation. To test this possibility, we performed time‐lapse confocal microscopy of developing ISVs in control and _B_α knockdown Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1 embryos between 34 and 47 hpf. At around 28 hpf, a primary network of ISVs derived from the DA reaches the dorsolateral roof of the neural tube and starts forming the DLAVs (Isogai et al, 2003). After connection and anastomosis of the different branches into the DLAV (around 1.5 dpf), these vessels start forming a functional lumen, which in control embryos normally widen and remain well defined at 2 dpf (Supplementary Movie 3; Figure 2F). By contrast, lumens from zB_α_a/b morphant ISVs appeared to be highly unstable, where lumens initially formed but then collapsed. By 2 dpf, the largest part of the ISVs and DLAV failed to establish a permanent functional lumen and had a narrowed appearance (Supplementary Movie 4; Figure 2F). Altogether, these data demonstrate that PP2A‐Bα is required for functional lumen maintenance during sprouting angiogenesis.

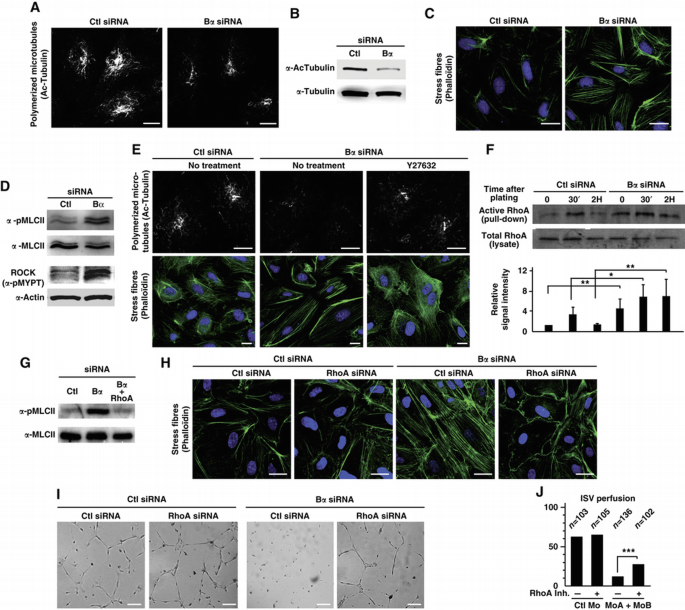

PP2A‐B α controls cytoskeleton dynamics in ECs via the RhoA/ROCK/MLC pathway

Next, we examined cytoskeleton dynamics in Bα‐deficient ECs, as they play a key role in controlling the EC shape changes (e.g., morphogenesis) that occur during the formation and maintenance of vascular lumen (Bayless and Davis, 2004; Hoang et al, 2010, 2011; Bayless and Johnson, 2011). We observed a significant decrease in tubulin acetylation in Bα‐depleted cells compared with control cells indicating that loss of PP2A‐Bα correlates with destabilized microtubules (Figure 3A and B). We also observed increased formation of polymerized actin stress fibres in ECs transfected with Bα siRNA, indicating that the absence of PP2A‐Bα affects actin dynamics (Figure 3C). Because these observations may reflect increased actomyosin contractility, we examined activity of the RhoA‐associated kinase ROCK and phosphorylation of its substrate Myosin Light Chain (MLC), which is required for non‐muscle myosin II activity and correlates with actomyosin contractility and stress fibre formation. Supporting the idea that deletion of PP2A‐Bα leads to activation of the ROCK/MLC pathway, we found that cells lacking PP2A‐Bα displayed a significantly higher ROCK activity (as revealed by increased phosphorylation of its downstream target MYPT) and MLC phosphorylation as compared with control cells (Figure 3D). In addition, inhibiting ROCK activity with Y27632 restored normal microtubule stability and actin polymerization in Bα siRNA‐treated cells (Figure 3E).

Figure 3

PP2A‐Bα controls cytoskeleton dynamics in ECs via the RhoA/ROCK/MLC pathway. (A and B) HUVECs transfected with control or PP2A‐Bα siRNA were analysed for their acetylated tubulin level by immunofluorescent staining (A) and by western blot analysis (B). Scale bars represent 10 μm. (C) Immunofluorescent analysis of stress fibres with phalloïdin staining in control or PP2A‐Bα siRNA‐transfected HUVECs. Nuclei are stained with Hoechst 32258 (blue). Scale bars represent 20 μm. (D) HUVECs transfected with siRNA against PP2A‐Bα, or a control siRNA were analysed by western blotting with antibody specific for phosphorylated MLC. Total MLC antibody was used as a loading control. In parallel, cell lysates were submitted to a ROCK activity assay using an in vitro kinase assay with recombinant MYPT1, blotted with a phospho‐MYPT1 antibody. (E) HUVECs transfected with PP2A‐Bα siRNA were treated, or not, with the ROCK inhibitor Y27632 for 30 min. Cells were then subjected to immunostaining for stabilized microtubules (Ac‐tubulin) and for stress fibres (phalloïdin). Nuclei are stained with Hoechst 2258 (blue). Scale bars represent 10 μm. (F) Western blot analysis of active RhoA during the matrigel tubulogenesis assay in control or PP2A‐Bα siRNA‐transfected HUVECs. Histogram represents densitometric analysis on three independent experiments calculating the ratio between bound active RhoA and total amount of RhoA in the lysate (Student's _t_‐test, *P<0.05, **P<0.01). (G) Lysates from HUVECs transfected with the indicated siRNA were analysed by western blotting with antibody specific for phosphorylated or total MLC as indicated. (H, I) HUVECs transfected with the indicated siRNA were subjected to immunostaining for stress fibres (phalloïdin) (H) or to a tubulogenesis assay (I). Scale bars represent 20 μm (H) and 150 μm (I). (J) Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1 embryos were injected with control Mo or with the MoA/MoB combination. At 28 hpf, the cell permeable RhoA inhibitor was injected into the circulation and perfusion of ISV was assessed as in Figure 2B. The graph shows the percentage of normal embryos, that is, having normal perfusion in all ISVs (Pearson's chi‐squared test, ***P<0.001).

Because finely regulated cytoskeleton dynamics and cell contractility are also important for cell adhesion (Parsons et al, 2010), we assessed the ability of Bα‐silenced ECs to attach to major ECM components. We found that knockdown of Bα was associated with a significant increase in cell adhesion onto fibronectin and to a lesser extend onto vitronectin, but not onto laminin or collagen (Supplementary Figure S3A and B). EC attachment to ECM is achieved through dynamic subcellular structures called integrin adhesions (Wolfenson et al, 2009). These adhesions are usually divided into three categories according to their molecular composition in signalling and structural proteins. Focal complexes (FX) are the first adhesion sites to appear at the cell periphery and are highly dynamic (Zaidel‐Bar et al, 2007). While most of the FX rapidly disappear, some mature into classical focal adhesions (FAs) which contain proteins such as paxillin and vinculin and reside at the end of stress fibres. FA can further mature into highly stable fibrilar adhesions (FBs), containing activated integrins but no paxillin (Parsons et al, 2010). Normal FA turnover requires dynamic microtubules (Stehbens and Wittmann, 2012), which prompted us to investigate adhesion maturation in Bα‐deficient cells. We found that ECs treated with siRNA against Bα formed on average a much higher number of paxillin‐containing adhesions (FX and FA) (Supplementary Figure S3C–E). In contrast, levels of activated β1 integrin were unaltered in Bα‐deficient ECs, indicating that PP2A‐Bα has no effect on stable FBs (Supplementary Figure S3C and F). Adhesion complexes observed in cells lacking PP2A‐Bα were significantly larger and mostly distributed over the entire basal surface, as opposed to control cells, in which small adhesions were mostly observed at the cell periphery (Supplementary Figure S3G and H). These observations indicate that the absence of PP2A‐Bα correlates with increased maturation of highly dynamic FX into FA. Of note, it has previously been reported that microtubule depolymerization and cell contraction are necessary for FX to develop into FA (Burridge et al, 1997). Altogether, our data are consistent with a model in which the lack of PP2A‐Bα reduces microtubule stability and increases cell contractility, resulting in excessive stability of EC–ECM adhesions.

The observations of activated ROCK, hyperphosphorylation of MLC, large adhesions and numerous contractile actin bundles in Bα‐deficient ECs are reminiscent of cells in which the small GTP‐binding protein RhoA is activated (Bershadsky et al, 1996; Ren et al, 1999; Watanabe et al, 1999). In addition, RhoA activation has been implicated in vascular lumen instability (Bayless and Davis, 2004; Im and Kazlauskas, 2007). These findings prompted us to examine the possibility that PP2A‐Bα might contribute to vascular lumen stability by suppressing RhoA activity in EC. In agreement with this hypothesis, we found upregulation of RhoA activity in PP2A‐Bα‐deficient ECs during tubulogenesis. The absence of Bα not only increases basal level of active RhoA but also promotes RhoA sustained activation during the in vitro morphogenesis Matrigel assay (Figure 3F).

To confirm this observation, we examined whether hyperactivation of the ROCK/MLC pathway and the consequent cytoskeleton alterations associated with the absence of PP2A‐Bα were dependent on RhoA. We found that knocking down RhoA restored background levels of MLC phosphorylation and prevented excessive formation of actin stress fibres in Bα‐depleted cells (Figure 3G and H). Supporting the idea that inhibition of RhoA signalling by PP2A is important for vascular stability, we found that silencing of RhoA largely rescued the in vitro tubulogenesis defects associated with loss of PP2A‐Bα (Figure 3I). To test whether PP2A‐Bα also represses RhoA in vivo, we injected a RhoA inhibitor in the circulation of developing zebrafish embryos, prior to ISV lumenization (at 28 hpf) and examined ISV perfusion 26 h post injection (hpi). Inhibition of RhoA activity had no impact on ISV lumen formation or stability in control embryos, but improved lumen stability in zB_α_a/b morphant embryos as a significantly higher proportion of embryos with normal perfusion in all ISVs was observed (Figure 3J). Collectively, these results demonstrate that an important function of PP2A‐Bα in ECs is to repress the RhoA/ROCK/MLC pathway to ensure proper regulation of cytoskeleton dynamics and cellular contractility, both of which are crucial for lumen maintenance (Bayless and Davis, 2004; Bayless and Johnson, 2011).

PP2A subunit Bα regulates key angiogenic genes involved in cytoskeleton regulation

To investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the PP2A‐Bα‐dependent regulation of cytoskeleton dynamics, we profiled genome‐wide gene expression changes in ECs lacking PP2A‐Bα. Bioinformatic analysis identified 75 genes whose expression was altered at least three‐fold following Bα silencing (57 upregulated and 18 downregulated genes), including genes involved in blood vessel morphogenesis and cell adhesion (Supplementary Figure S4A). Among the top 15 most upregulated genes, we identified ArgBP2, a gene coding for a member of the sorbin and SH3 homology domain‐containing (SoHo) family of adaptor proteins implicated in cytoskeleton‐dependent processes (Kioka et al, 2002) (Supplementary Figure S4B). Induction of ArgBP2 expression following PP2A‐Bα inactivation was confirmed by qPCR in HUVECs and in _zB_α_a/zB_α_b_‐deficient zebrafish embryos (Supplementary Figure S4C and D).

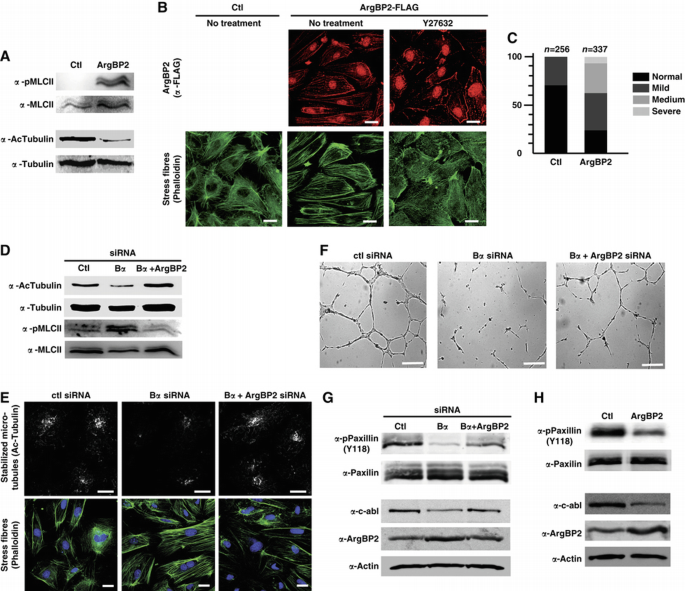

ArgBP2 is considered as a scaffold protein that coordinates multiple signalling pathways converging on the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton (Cestra et al, 2005). We thus hypothesized that increased levels of ArgBP2 could account for the defects in cytoskeleton dynamics and cell–ECM adhesion associated with loss of PP2A‐Bα in ECs. Consistent with this hypothesis, we verified that ectopic expression of ArgBP2 in HUVECs recapitulated the cytoskeleton effects of Bα knockdown. Indeed, overexpression of ArgBP2 increased actomyosin cell contractility and correlated with destabilization of the microtubule network (Figure 4A and B). The ArgBP2‐induced cell contractility was abolished by the Y27632 inhibitor indicating that ArgBP2 affects actin polymerization through the ROCK pathway (Figure 4B). ArgBP2‐overexpressing ECs also exhibited more numerous and aberrantly large FAs and increased adhesiveness onto fibronectin (Supplementary Figure S4E and F). Supporting our model in vivo, overexpression of ArgBP2 in zebrafish perfectly duplicated lumen stability defects associated wit PP2A‐Bα deficiency (Figure 4C). Conversely, preventing expression of ArgBP2 in a Bα‐deficient background partially but significantly restored normal cytoskeleton contractility (Figure 4D and E) and adhesion properties in EC (Supplementary Figure S4G–I). More importantly, co‐silencing of Bα and ArgBP2 reverted the tubulogenesis defects associated with the absence of PP2A‐Bα (Figure 4F). Altogether, these observations support the hypothesis that ArgBP2 is a key effector of Bα‐mediated regulation of cytoskeletal rearrangements in ECs.

Figure 4

PP2A subunit Bα regulates key angiogenic genes involved in cytoskeleton regulation. (A) A DNA‐construction coding for ArgBP2‐Flag was transfected into HUVECs. Forty‐eight hours after transfection, total cell lysate was subjected to western blot analysis with antibodies specific for phosphorylated MLC and for acetylated tubulin. Total MLC and tubulin antibodies were used as loading controls. (B) HUVECs overexpressing ArgBP2‐Flag or a control vector were subjected to confocal microscopy analysis to detect the patterning of stress fibres using phalloïdin staining and localization of ArgBP2 using an anti‐FLAG antibody. In parallel, ArgBP2 overexpressing cells were treated with the ROCK inhibitor Y27632 for 30 min and immunostained for stress fibres. Scale bars represent 20 μm. (C) Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1;Tg(gata1a:dsRed)sd2 embryos were injected with RNA coding for human ArgBP2. At 50 hpf, perfusion of ISV was assessed as in Figure 2B (_n_=number of embryos; Pearson's chi‐squared test: P<0.001). (D) HUVECs were transfected with control, PP2A‐Bα siRNA or co‐transfected with siRNA against PP2A‐Bα and ArgBP2. Total cell lysate was subjected to western blot analysis with antibodies specific for acetylated tubulin and for phosphorylated MLC. Total tubulin and MLC antibodies were used as loading controls. (E) Immunofluorescent analysis of HUVECs transfected as in (D) and stained for acetylated tubulin and for phalloïdin. Scale bars represent 10 μm. (F) HUVECs transfected as in (D) were cultured for 48 h before being seeded onto Matrigel. Micrographs of one representative experiment out of five are shown. Scale bars represent 200 μm. (G) HUVECs were transfected with control, PP2A‐Bα siRNA or co‐transfected with siRNA against PP2A‐Bα and ArgBP2. Total cell lysate was subjected to western blot analysis with antibodies specific for phosphorylated Paxillin, c‐Abl and ArgBP2. Total Paxillin and actin antibodies were used as a loading controls. (H) Total cell lysate from cells treated as in (A) was subjected to western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies.

In an effort to understand how ArgBP2 might affect cytoskeleton dynamics, we examined the phosphorylation of paxillin. We considered that paxillin phosphorylation was likely to be altered by ArgBP2 for the following reasons: (1) ArgBP2 binds to paxillin, c‐Abl and PTP‐PEST (Roignot and Soubeyran, 2009); (2) c‐Abl phosphorylates Paxillin on tyrosine 118 (Y118), a site that is targeted for dephosphorylation by PTP‐PEST (Deakin and Turner, 2008); (3) phosphorylation of paxillin is a key event in coordinating the roles of paxillin in rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton. Lack of paxillin phosphorylation at Y118 would be expected to promote actin cell contraction and formation of robust adhesion complexes through activation of the RhoA/ROCK pathway, similarly to what we observed in cells lacking PP2A‐Bα (Tsubouchi et al, 2002). We thus examined modulation of paxillin phosphorylation following PP2A‐Bα knockdown and consequent increase in ArgBP2 levels. We found that cells lacking PP2A‐Bα showed no phosphorylation of paxillin at Y118 (Figure 4G). The causal role of ArgBP2 in this lack of paxillin phosphorylation was confirmed by two approaches. First, cells expressing exogenous ArgBP2 showed reduced paxillin phosphorylation (Figure 4H). Second, co‐silencing experiments demonstrated that preventing expression of ArgBP2 in siBα‐treated cells restored a significant phosphorylation of paxillin Y118 (Figure 4G). Because ArgBP2 has been shown to negatively regulate c‐Abl function by promoting its degradation (Soubeyran et al, 2003), we next hypothesized that paxillin phosphorylation deficiency concomitant to PP2A‐Bα deletion could be due to a decrease in c‐Abl protein level. Supporting this idea, we found that enhanced expression of ArgBP2, by silencing PP2A‐Bα or ectopically overexpressing ArgBP2, correlates with reduced levels of c‐Abl (Figure 4G and H).

PP2A regulatory subunit Bα regulates vascular integrity through the control of class IIa HDAC7 transcriptional activity

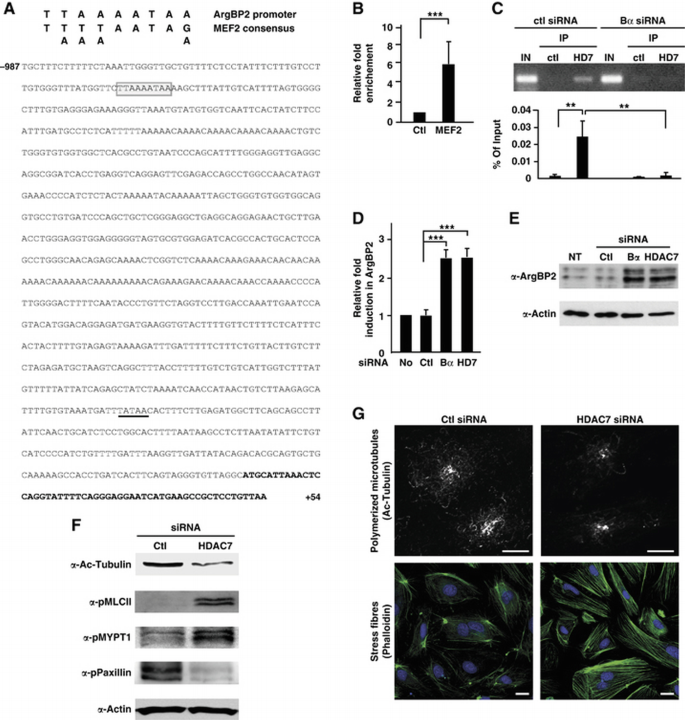

In order to determine the mechanisms by which PP2A‐Bα regulates the expression of ArgBP2, we searched for conserved regulatory sequences in the ArgBP2 promoter. In silico analysis identified a binding site for the myocyte enhancer factor‐2 (MEF2) transcription factors, a family of transcriptional regulators that play critical roles in blood vessel formation (Bi et al, 1999) (Figure 5A). The presence of MEF2 on the ArgBP2 promoter was confirmed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) (Figure 5B). MEF2 is known to recruit class IIa HDACs to repress its target genes, and the ability of class IIa HDACs to inhibit MEF2‐dependent transcription relies on their dephosphorylation‐dependent nuclear localization (Martin et al, 2007). In addition, we have previously shown that HDAC7, a class IIa HDAC critical for vascular stability is dephosphorylated by an unidentified PP2A holoenzyme (Martin et al, 2008). On the basis of these considerations, we elaborated a model in which PP2A‐Bα would participate in the proper regulation of EC cytoskeleton dynamics and maintenance of vascular integrity by controlling HDAC7 dephosphorylation and ensuring transcriptional regulation of crucial HDAC7‐targeted genes such as ArgBP2.

Figure 5

PP2A regulatory subunit Bα regulates vascular integrity through the control of class IIa HDAC7 transcriptional activity. (A) Sequence of the ArgBP2 promoter. Sequences in bold correspond to the most upstream sequences found in the ArgBP2 mRNA, isoform 2 (NM_021069.4). A potential TATA box is underlined. A perfect MEF2 consensus binding site (box) was identified at position −923 relatively to the most upstream residue of the ArgBP2 mRNA. (B) MEF2 binding on the ArgBP2 promoter was analysed in HUVECs by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiment. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with rabbit IgG or antibody against MEF2 and bound genomic DNA was analysed by real‐time PCR using a specific pair of primers spanning the MEF2 binding motif of the ArgBP2 promoter. Histograms illustrate the relative fold enrichment of MEF2 at the ArgBP2 promoter calculated as described in Materials and methods from three independent experiments. (C) ChIP assays were performed on HUVECs transfected with control or PP2A‐Bα siRNA. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with rabbit IgG or antibody against HDAC7. Real‐time PCR was achieved using a specific pair of primers spanning the MEF2 binding motif of the ArgBP2 promoter. Amplification products were analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Histograms correspond to the amount of HDAC7 recruitment, calculated relatively to the input from three independent experiments. (D) RNA from HUVECs transfected with control, PP2A‐Bα or HDAC7 siRNA, or not transfected was subjected to real‐time PCR analysis using ArgBP2‐specific primers. ArgBP2 expression was expressed relatively to the control. (E) Lysates from HUVECs transfected with control, PP2A‐Bα or HDAC7 siRNA, or not transfected were subjected to western blot analysis using an antibody directed against ArgBP2. Actin antibody was used as a control. (F) HUVECs transfected with siRNA against HDAC7, or a control siRNA were analysed by western blotting with antibodies specific for acetylated tubulin, phosphorylated MLC and phosphorylated Paxillin. Actin antibody was used as a loading control. In parallel, cell lysates were submitted to a ROCK activity assay blotted with an antibody against phosphorylated MYPT1. (G) HUVECs transfected as in (F) were subjected to confocal microscopy analysis using acetylated tubulin antibody. Cells were also stained for phalloïdin to visualize stress fibres. Scale bars represent 10 μm. Data are mean±s.d.; Student's _t_‐test: **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Supporting our model, we observed a physical interaction between PP2A‐Bα and HDAC7 in ECs and confirmed that HDAC7 is a bona fide substrate for a PP2A‐A/C/Bα holoenzyme using in vitro dephosphorylation assays (Supplementary Figure S5A and B). In addition, HDAC7 was hyperphosphorylated and localized in the cytoplasm of PP2A‐Bα‐depleted ECs (Supplementary Figure S5C and D). Consequently, recruitment of HDAC7 to the ArgBP2 promoter was abolished (Figure 5C). Detachment of HDAC7 from the ArgBP2 promoter abrogated its transcriptional repressive activity: in the absence of PP2A‐Bα, ArgBP2 expression was induced to levels comparable to those observed in cells lacking HDAC7 (Figure 5D and E). To extend these observations to the entire genome, the transcriptomes of ECs silenced for PP2A‐Bα and HDAC7 were compared. Analysis of microarray data revealed that genes significantly modulated in response to PP2A‐Bα knockdown were similarly affected following HDAC7 silencing, thus demonstrating that loss of PP2A‐Bα and HDAC7 have comparable genome‐wide transcriptional consequences (Supplementary Figure S5E). In addition, knocking down HDAC7 recapitulated all the phenotypes associated with deletion of PP2A‐Bα in ECs, that is, microtubule destabilization, hyperactivation of the RhoA/ROCK/MLC pathway, increased actomyosin contractility (Figure 5F and G), accumulation of mature FA and specific increased adhesion towards fibronectin and vitronectin (Supplementary Figure S5F and G). Together with the previously reported observations that lack of HDAC7 is associated with a failure to maintain vascular integrity in vitro (Mottet et al, 2007; Martin et al, 2008) and in vivo (Chang et al, 2006), we conclude that PP2A‐Bα regulates vascular integrity by governing HDAC7 activity.

Discussion

Here, using a combination of in vitro cell biology and in vivo mosaic loss of function studies we identify a cell‐autonomous function of PP2A‐Bα in ECs, which is critical for blood vessel development. We show that loss of PP2A‐Bα in ECs is associated with deregulation of cytoskeleton dynamics evidenced by increased actomyosin contractility and microtubule depolymerization. In addition, basal adhesion contacts accumulate, resulting in enhanced adhesion to the ECM. The inability of Bα‐deficient ECs to properly rearrange their cytoskeleton and modify their adhesion to ECM impairs establishment of stable vascular lumen.

In vitro studies previously showed that inhibition of general PP2A enzymatic activity impairs EC tubulogenesis, however whether and how PP2A might be involved in blood vessel development in vivo is unexplored (Gabel et al, 1999; Martin et al, 2008). Also, the family of PP2A enzymes is expected to have a large number of molecular targets and it has been unclear whether distinct PP2A holoenzymes mediate selective functions in ECs. In fact, phosphatases are often considered promiscuous and there is generally little detailed knowledge on whether specific phosphatases have a limited set of targets, conferring specific modulation of individual pathways and distinct cellular functions. Similarly, HDACs are expected to influence the activity of various proteins through their enzymatic deacetylase activity, not least affecting transcriptional activity of a large variety of genes. With this in mind, it is highly remarkable that the Bα PP2A subunit orchestrates a rather specific cellular function, acting through HDAC7 regulation, to modify EC behaviour required for lumen stabilization. To our knowledge, this is the first study linking a specific PP2A holoenzyme to an important developmental process, that is, stabilization of the vascular network.

Cellular mechanisms of lumen stabilization

Interestingly, PP2A‐Bα appears to be dispensable for the correct patterning of the vasculature. In the absence of PP2A‐Bα, primary and secondary vessels in the head and in the trunk branch and develop normally, along the predefined elongation pathways. Thus, the observed deregulated adhesion to matrix substrates and altered EC contractility does little to affect the ability of tip cells to migrate along the somite boundaries and read both attractive and repulsive guidance cues. Instead, once connected the ISVs initially attempted to open up a lumen that then collapsed. Importantly, the few ISVs that succeeded in stabilizing lumen in PP2A‐Bα embryos show normal circulation, indicating that lumen collapse was not caused by lack of blood flow, which is known to be important in the formation of stable functional ISVs (Isogai et al, 2003). In addition, the transplantation experiments demonstrate that ISV lumen collapse still occurs in a wild‐type circulation background, even when a single morphant cell is present in the ISV.

The cellular and molecular mechanisms driving vascular lumen formation in vivo remain controversial, and even less is known about the molecular pathways that control the stability of EC tubular structures (Iruela‐Arispe and Davis, 2009). In zebrafish, primary vessels seem to lumenize by opening up an intercellular space inside the angioblast cord (Jin et al, 2005). Secondary vessels such as ISVs appear to form lumen through uni‐ and trans‐cellular mechanisms (Kamei et al, 2006; Blum et al, 2008; Strilic et al, 2009, 2010; Wang et al, 2010). The lack of PP2A‐Bα had no impact on the ability of ECs to generate lumen indicating that formation of unicellular, intercellular lumen or both process do not require PP2A‐Bα function. Interestingly, however, lumen collapse not only occurred when all ECs forming an ISV lacked PP2A‐Bα function, but also in mosaic vessels containing several or even just one EC lacking PP2A‐Bα. This suggests that PP2A‐Bα morphant ECs can cause collapse of a lumen jointly formed with WT cells in an intercellular configuration. Given our finding of a PP2A‐Bα regulation of cell adhesion and contractility, it is tempting to speculate that stable lumen formation requires a balanced regulation of cell contractility between neighbouring cells. Notably, the axial vessels, the DA and PCV showed no lumen defects, suggesting that the molecular mechanisms of lumen stabilization differ in different blood vessels.

The molecular mechanism underlying proper spatial and temporal control of the PP2A/HDAC7/ArgBP2 axis during lumen stabilization and angiogenesis is an exciting issue. While still a matter of debate, the current model suggests that most of the PP2A regulation is achieved through association of specific regulatory subunits with the PP2A‐A/C catalytic core, generating a collection of PP2A holoenzymes with specific properties. The intimate mechanisms that dictate why and how a regulatory subunit integrates into the holoenzyme are still obscure but involve post‐translational modifications of the various PP2A subunits (Sents et al, 2012). Identifying the outside‐in signalling and putative PP2A‐A/Bα/C holoenzyme post‐translational modifications associated with lumen stabilization needs to await further progress on the general mechanisms of PP2A regulation.

PP2A effects on the cytoskeleton and mechanism of lumen stabilization

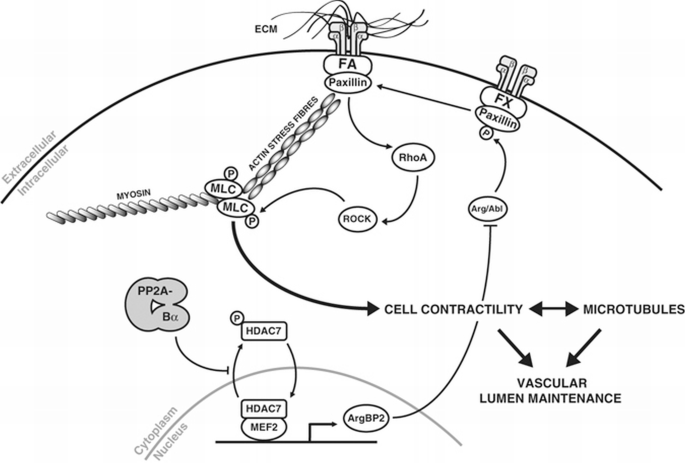

The few examples of intracellular signalling pathways that regulate lumen formation and stabilization in vitro all converge onto the cytoskeleton (Bayless and Johnson, 2011). Our data support this functional link. Unfortunately, because of technical issues, in particular because in vivo F‐actin structures are less conspicuous than stress fibres in vitro we were not able to properly demonstrate cytoskeleton alterations in vivo. Mechanistically, our findings are also consistent with the few studies that have investigated the involvement of PP2A in EC cytoskeleton organization, which showed that increasing PP2A activity (by overexpression of the C or A subunits) reduces F‐actin stress fibre formation and promotes microtubule stability (Tar et al, 2006). We report here that these effects can be specifically attributed to Bα‐containing PP2A holoenzymes. Earlier studies in other cell types have shown that the PP2A‐Bα trimer holoenzyme binds to microtubules and is necessary to maintain their polymerization (Sontag et al, 1995; Nunbhakdi‐Craig et al, 2007). In neurons, microtubule destabilization following inhibition of PP2A has been attributed to abnormal phosphorylation of the Alzheimer‐related protein tau (Merrick et al, 1997; Sontag et al, 1999). In ECs, we provide evidence that the function of Bα in emerging blood vessels is to recruit a specific A/C/Bα PP2A holoenzyme towards HDAC7, a key transcriptional regulator. Dephosphorylation of HDAC7 by a Bα‐containing PP2A holoenzyme ensures nuclear localization of HDAC7 and transcriptional repression of HDAC7‐target genes coding for proteins involved in the regulation of cytoskeleton dynamics (Figure 6). Supporting this model, we found that silencing of PP2A‐Bα or HDAC7 in vitro had identical consequences on EC cytoskeleton organization, disrupting microtubule networks and increasing contractility.

Figure 6

Model of PP2A‐Bα regulation of vascular lumen maintenance.

Regarding the function of PP2A in lumen maintenance, we considered a potential role for p21‐activated kinases PAKs, the activity of which has previously been linked to activation of PP2A (Sheehan et al, 2007). PAKs are a family of serine‐threonine kinases that act downstream of the small GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1 and have been implicated in lumen formation and maturation via regulation of EC cytoskeletal organization (Galan Moya et al, 2009). In particular, PAK2 and PAK4 are required for various aspects of EC lumen formation in vitro (Koh et al, 2009), but their roles in vivo remain untested. Despite our efforts, we did not observe any modification in the activities of PAK2, PAK4 or their upstream GTPases Cdc42 or Rac1 in the absence of PP2A‐Bα. Instead, our observations identify RhoA as the main Rho GTPase involved in the control of vascular stability by the PP2A‐Bα/HDAC7 pathway. Our results are thus in accordance with previous studies showing that collapse of EC lumen following microtubule destabilization is independent of Rac1 or Cdc42 but rather relies on RhoA activation (Bayless and Davis, 2004).

Transcriptional targets of HDAC7 regulating EC cytoskeleton

While other PP2A effectors in lumen maintenance might exist, we found that deletion of HDAC7 phenocopies the transcriptional changes and cytoskeleton defects caused by Bα silencing in ECs. These results raise the provocative idea that the most prominent function of Bα‐containing PP2A holoenzymes in ECs is to dephosphorylate HDAC7 and ensure proper regulation of its target genes. The PP2A‐Bα/HDAC7 axis controls the expression of a wide array of genes, including ArgBP2, which we identify as a key effector in PP2A‐Bα/HDAC7 cytoskeleton functions. First, we found that ArgBP2 localizes on actin fibres and cell‐adhesion sites. Second, we verified that overexpression of ArgBP2 recapitulates PP2A‐Bα or HDAC7 inhibition in ECs, leading to RhoA‐dependent increased stress fibre stability, enhanced contractility and microtubule collapse. Finally, in vitro co‐silencing experiments rescued most of the cellular effects associated with PP2A‐Bα knockdown, thus identifying ArgBP2 as the pivotal effector of PP2A‐Bα in the regulation of EC cytoskeletal properties, at least in vitro. How ArgBP2 may induce microtubule disruption and cytoskeleton alterations in ECs, leading to lumen collapse remains an open question.

One attractive hypothesis relates to our observations that ArgBP2 modulates RhoA activity through preventing the phosphorylation of paxillin at Y118 (Tsubouchi et al, 2002; Deakin and Turner, 2008). Excessive activation of the RhoA/ROCK pathway would then alter cytoskeleton dynamics and induce vascular lumen collapse (Figure 6). Of potential interest, a second pathway by which ArgBP2 could inhibit RhoA is through inactivation of the GTPase activating protein p190RhoGAP. When phosphorylated (activated) p190RhoGAP downregulates RhoA by stimulating its intrinsic rate of GTP hydrolysis (Chang et al, 1995). Interestingly, and similarly to paxillin, phosphorylation of p190RhoGAP is competitively regulated by Arg/c‐Abl and PTP‐PEST, whose activities are controlled by ArgBP2 (Hernandez et al, 2004; Sastry et al, 2006). Since ArgBP2 binds many protein tyrosine kinases, phosphatases and actin‐related proteins, more work will be necessary to decipher the complete set of molecular effectors mediating the effects of PP2A‐Bα holoenzymes on the cytoskeleton and maintenance of vascular networks.

Therapeutic perspectives

Understanding the molecular pathways and cellular morphogenetic events underlying establishment of a seamless and contiguous network of blood vessels is essential for the development of angiogenesis‐based therapies. For instance, microtubule depolymerizing agents are now considered as potent vascular disrupting agents (VDAs) and are being tested in novel anti‐angiogenic approaches. While our study strengthens the substantial evidence linking cytoskeleton dynamics to vascular lumen stabilization, it also provides new access points along the PP2A/HDAC7/ArgBP2 axis for therapeutic interventions in angiogenesis‐related disorders such as cancer or eye disease.

Materials and methods

Immunofluorescence

SiRNA‐transfected cells were seeded onto fibronectin‐coated coverslips 1 day after transfection. The next day, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X‐100, blocked in BSA and incubated overnight with the appropriate primary antibodies. Cells were then further incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies for 1 h. After washing, cells were mounted with Fluoro‐Gel (Laborimpex) and processed for immunofluorescence using a Nikon fluorescence confocal microscope (Nikon A1R).

For acetyl‐tubulin staining, HUVECs were permeabilized 1 min in 0.1% Triton X in PHEM buffer, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PHEM buffer and then submitted to the same protocol as above.

Tube formation assays

Forty‐eight hours after transfection with the indicated siRNA, HUVECs were processed for the Matrigel assays as described (Martin et al, 2008). Briefly, 5 × 104 cells were cultured in a 24‐well plate coated with 100 μl of Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix (BD Biosciences). Tube length was quantified after 12 h by measuring the cumulative tube length in five random microscopic fields using the WCIF ImageJ software.

For apoptosis inhibition experiments, HUVECs were treated with 100 μM of ZVAD‐FMK during the entire assay.

For time‐lapse experiment, siRNA‐transfected HUVECs were seeded onto Matrigel‐coated chambered coverglass in the culture chamber of a confocal microscope (Nikon A1R). DIC pictures were taken every 14 min using the autofocus tool of the microscope.

Spheroid‐based angiogenesis assay

Endothelial cell spheroids of defined cell number were generated as described previously (Potente et al, 2005). Twenty‐four hours after transfection, spheroids of siRNA‐treated HUVECs were generated overnight and embedded into collagen gels. Angiogenic activity was quantified by measuring the cumulative length and number of the sprouts that had grown out of each spheroid using the ImageJ software.

Adhesion assay

HUVECs were incubated in vitronectin‐, fibronectin‐, laminin‐, or type I collagen‐precoated wells for 30 min. After washing, attached cells were stained with crystal violet. Incorporated dye was released by cell permeabilization and measured by reading absorbance at 560 nm.

RhoA pull‐down activity assay

HUVECs were released from matrigel at the indicated time by incubation in cell recovery solution (BD Biosciences) for 2 h at 4°C. After cells recovery, levels of active RhoA were measured using the Rho Activity Assay (Cytoskeleton Inc.) according to the manufacturers’ protocol. Briefly, cell lysate was incubated for 1 h at 4°C with GST‐Rhotekin beads. Bound activated RhoA was eluted from the beads and analysed by western blotting using RhoA antibody.

Zebrafish

Fish of the Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1 (Lawson and Weinstein, 2002)_, Tg(fli1a:nEGFP)y7 (_Roman et al, 2002), Tg(gata1a:dsRed)sd2 (Traver et al, 2003) and Tg(fli1a:RFP) line were maintained according to EU regulations on laboratory animals. Knockdown experiments were performed by injecting embryos at the one‐ to two‐cell stage with 10 ng of single morpholino or 2 × 10 ng of combined morpholinos (A1+B1 or A2+B2). Rescue and ectopic overexpression experiments were performed by injecting RNA molecules from in vitro transcription reactions using linearized PCS2+ vector coding for human PP2A‐Bα or ArgBP2. For RhoA inhibition rescue experiments, 3 nl of the C3 exoenzyme transferase (2 μg/ml) was injected into the circulation of 28 hpf embryos. Screening was performed by counting the number of perfused ISVs in a 10‐somite region above the yolk extension at 54 hpf. Embryos with 10 or 9 perfused ISVs were considered as ‘normal’; embryos with 8, 7 or 6 perfused ISVs were considered as having a ‘mild’ phenotype; embryos with 5, 4 or 3 perfused ISVs were classified as having ‘medium’ phenotype; embryos with 2, 1 or 0 perfused ISVs were considered as a ‘severe’ phenotype.

Bright field pictures were taken from fixed embryos using a stereomicroscope, whereas confocal pictures were taken on living embryos using a Nikon A1R, Leica SP5 or Leica SP8 confocal microscope. For real‐time imaging of circulating blood cells, living Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1;Tg(gata1a:DsRed)sd2 embryos were mounted on an agarose gel 68 h after injection. Frames were taken every 0.017 s during 1.5 min using the resonant mode of the confocal Nikon A1R microscope. For real‐time imaging of ISV outgrowth and lumenization control and PP2A‐Bα morphant Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1 embryos were embedded in low‐melting point agarose gel and imaged every 25 min on a confocal Leica SP5 microscope.

Vessel functionality was analysed by angiography. Five nanolitres of Q705 quantum dots (Life Technologies) was injected into the circulation of 1 dpf embryos and vessel perfusion was analysed at 2 dpf by confocal microscopy.

For transplantation experiments control or PP2A‐Bα morphant donor Tg(fli1a:eGFP)y1 embryos and wild‐type Tg(fli1a:RFP) host embryos were manually dechorionated and transferred to wells in an agarose plate. About 20–30 cells were transplanted from donor embryos to the margin of host embryos at oblong/sphere stage (about 5 hpf). Host embryos were further grown at 28°C until analysis at 55 hpf.

Statistical analysis

Unless stated otherwise, graph values are presented as mean±standard deviation, calculated on at least three independent experiments. Significance was determined using a two‐tailed Student's _t_‐test or a Pearson's chi‐squared test.

References

- Adams RH, Alitalo K (2007) Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 464–478

Google Scholar - Bayless KJ, Davis GE (2004) Microtubule depolymerization rapidly collapses capillary tube networks in vitro and angiogenic vessels in vivo through the small GTPase Rho. J Biol Chem 279: 11686–11695

Google Scholar - Bayless KJ, Johnson GA (2011) Role of the cytoskeleton in formation and maintenance of angiogenic sprouts. J Vasc Res 48: 369–385

Google Scholar - Bengtsson L, Schwappacher R, Roth M, Boergermann JH, Hassel S, Knaus P (2009) PP2A regulates BMP signalling by interacting with BMP receptor complexes and by dephosphorylating both the C‐terminus and the linker region of Smad1. J Cell Sci 122: 1248–1257

Google Scholar - Bershadsky A, Chausovsky A, Becker E, Lyubimova A, Geiger B (1996) Involvement of microtubules in the control of adhesion‐dependent signal transduction. Curr Biol 6: 1279–1289

Google Scholar - Bi W, Drake CJ, Schwarz JJ (1999) The transcription factor MEF2C‐null mouse exhibits complex vascular malformations and reduced cardiac expression of angiopoietin 1 and VEGF. Dev Biol 211: 255–267

Google Scholar - Blum Y, Belting HG, Ellertsdottir E, Herwig L, Luders F, Affolter M (2008) Complex cell rearrangements during intersegmental vessel sprouting and vessel fusion in the zebrafish embryo. Dev Biol 316: 312–322

Google Scholar - Brownlee CW, Klebba JE, Buster DW, Rogers GC (2011) The Protein Phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit Twins stabilizes Plk4 to induce centriole amplification. J Cell Biol 195: 231–243

Google Scholar - Burridge K, Chrzanowska‐Wodnicka M, Zhong C (1997) Focal adhesion assembly. Trends in cell biology 7: 342–347

Google Scholar - Cestra G, Toomre D, Chang S, De Camilli P (2005) The Abl/Arg substrate ArgBP2/nArgBP2 coordinates the function of multiple regulatory mechanisms converging on the actin cytoskeleton. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 1731–1736

Google Scholar - Chan LY, Amon A (2009) The protein phosphatase 2A functions in the spindle position checkpoint by regulating the checkpoint kinase Kin4. Genes Dev 23: 1639–1649

Google Scholar - Chang JH, Gill S, Settleman J, Parsons SJ (1995) c‐Src regulates the simultaneous rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton, p190RhoGAP, and p120RasGAP following epidermal growth factor stimulation. J Cell Biol 130: 355–368

Google Scholar - Chang S, Young BD, Li S, Qi X, Richardson JA, Olson EN (2006) Histone Deacetylase 7 Maintains Vascular Integrity by Repressing Matrix Metalloproteinase 10. Cell 126: 321–334

Google Scholar - Deakin NO, Turner CE (2008) Paxillin comes of age. J Cell Sci 121: 2435–2444

Google Scholar - Foley EA, Maldonado M, Kapoor TM (2011) Formation of stable attachments between kinetochores and microtubules depends on the B56‐PP2A phosphatase. Nat Cell Biol 13: 1265–1271

Google Scholar - Gabel S, Benefield J, Meisinger J, Petruzzelli GJ, Young M (1999) Protein phosphatases 1 and 2A maintain endothelial cells in a resting state, limiting the motility that is needed for the morphogenic process of angiogenesis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 121: 463–468

Google Scholar - Galan Moya EM, Le Guelte A, Gavard J (2009) PAKing up to the endothelium. Cell Signal 21: 1727–1737

Google Scholar - Geudens I, Gerhardt H (2011) Coordinating cell behaviour during blood vessel formation. Development 138: 4569–4583

Google Scholar - Guenebeaud C, Goldschneider D, Castets M, Guix C, Chazot G, Delloye‐Bourgeois C, Eisenberg‐Lerner A, Shohat G, Zhang M, Laudet V, Kimchi A, Bernet A, Mehlen P (2010) The dependence receptor UNC5H2/B triggers apoptosis via PP2A‐mediated dephosphorylation of DAP kinase. Mol Cell 40: 863–876

Google Scholar - Hernandez SE, Settleman J, Koleske AJ (2004) Adhesion‐dependent regulation of p190RhoGAP in the developing brain by the Abl‐related gene tyrosine kinase. Curr Biol 14: 691–696

Google Scholar - Hoang MV, Nagy JA, Fox JE, Senger DR (2010) Moderation of calpain activity promotes neovascular integration and lumen formation during VEGF‐induced pathological angiogenesis. PLoS One 5: e13612

Google Scholar - Hoang MV, Nagy JA, Senger DR (2011) Cdc42‐mediated inhibition of GSK‐3beta improves angio‐architecture and lumen formation during VEGF‐driven pathological angiogenesis. Microvasc Res 81: 34–43

Google Scholar - Im E, Kazlauskas A (2007) Src family kinases promote vessel stability by antagonizing the Rho/ROCK pathway. J Biol Chem 282: 29122–29129

Google Scholar - Iruela‐Arispe ML, Davis GE (2009) Cellular and molecular mechanisms of vascular lumen formation. Dev Cell 16: 222–231

Google Scholar - Isoda M, Sako K, Suzuki K, Nishino K, Nakajo N, Ohe M, Ezaki T, Kanemori Y, Inoue D, Ueno H, Sagata N (2011) Dynamic regulation of Emi2 by Emi2‐bound Cdk1/Plk1/CK1 and PP2A‐B56 in meiotic arrest of Xenopus eggs. Dev Cell 21: 506–519

Google Scholar - Isogai S, Lawson ND, Torrealday S, Horiguchi M, Weinstein BM (2003) Angiogenic network formation in the developing vertebrate trunk. Development 130: 5281–5290

Google Scholar - Janssens V, Goris J (2001) Protein phosphatase 2A: a highly regulated family of serine/threonine phosphatases implicated in cell growth and signalling. Biochem J 353: 417–439

Google Scholar - Jayadeva G, Kurimchak A, Garriga J, Sotillo E, Davis AJ, Haines DS, Mumby M, Grana X (2010) B55alpha PP2A holoenzymes modulate the phosphorylation status of the retinoblastoma‐related protein p107 and its activation. J Biol Chem 285: 29863–29873

Google Scholar - Jin SW, Beis D, Mitchell T, Chen JN, Stainier DY (2005) Cellular and molecular analyses of vascular tube and lumen formation in zebrafish. Development 132: 5199–5209

Google Scholar - Kamei M, Saunders WB, Bayless KJ, Dye L, Davis GE, Weinstein BM (2006) Endothelial tubes assemble from intracellular vacuoles in vivo. Nature 442: 453–456

Google Scholar - Kioka N, Ueda K, Amachi T (2002) Vinexin, CAP/ponsin, ArgBP2: a novel adaptor protein family regulating cytoskeletal organization and signal transduction. Cell Struct Funct 27: 1–7

Google Scholar - Koh W, Sachidanandam K, Stratman AN, Sacharidou A, Mayo AM, Murphy EA, Cheresh DA, Davis GE (2009) Formation of endothelial lumens requires a coordinated PKCepsilon‐, Src‐, Pak‐ and Raf‐kinase‐dependent signaling cascade downstream of Cdc42 activation. J Cell Sci 122: 1812–1822

Google Scholar - Lawson ND, Weinstein BM (2002) In vivo imaging of embryonic vascular development using transgenic zebrafish. Dev Biol 248: 307–318

Google Scholar - Le Guelte A, Galan‐Moya EM, Dwyer J, Treps L, Kettler G, Hebda JK, Dubois S, Auffray C, Chneiweiss H, Bidere N, Gavard J (2012) Semaphorin 3A elevates endothelial cell permeability through PP2A inactivation. J Cell Sci 125: 4137–4146

Google Scholar - Manchado E, Guillamot M, de Carcer G, Eguren M, Trickey M, Garcia‐Higuera I, Moreno S, Yamano H, Canamero M, Malumbres M (2010) Targeting mitotic exit leads to tumor regression in vivo: modulation by Cdk1, Mastl, and the PP2A/B55alpha,delta phosphatase. Cancer Cell 18: 641–654

Google Scholar - Martin M, Kettmann R, Dequiedt F (2007) Class IIa histone deacetylases: regulating the regulators. Oncogene 26: 5450–5467

Google Scholar - Martin M, Potente M, Janssens V, Vertommen D, Twizere JC, Rider MH, Goris J, Dimmeler S, Kettmann R, Dequiedt F (2008) Protein phosphatase 2A controls the activity of histone deacetylase 7 during T cell apoptosis and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 4727–4732

Google Scholar - Merrick SE, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM (1997) Selective destruction of stable microtubules and axons by inhibitors of protein serine/threonine phosphatases in cultured human neurons. J Neurosci 17: 5726–5737

Google Scholar - Merrill RA, Slupe AM, Strack S (2012) N‐terminal phosphorylation of protein phosphatase 2A/Bbeta2 regulates translocation to mitochondria, dynamin‐related protein 1 dephosphorylation, and neuronal survival. FEBS J 280: 662–673

Google Scholar - Mottet D, Bellahcene A, Pirotte S, Waltregny D, Deroanne C, Lamour V, Lidereau R, Castronovo V (2007) Histone deacetylase 7 silencing alters endothelial cell migration, a key step in angiogenesis. Circ Res 101: 1237–1246

Google Scholar - Nunbhakdi‐Craig V, Schuechner S, Sontag JM, Montgomery L, Pallas DC, Juno C, Mudrak I, Ogris E, Sontag E (2007) Expression of protein phosphatase 2A mutants and silencing of the regulatory B alpha subunit induce a selective loss of acetylated and detyrosinated microtubules. J Neurochem 101: 959–971

Google Scholar - Parsons JT, Horwitz AR, Schwartz MA (2010) Cell adhesion: integrating cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular tension. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 633–643

Google Scholar - Potente M, Gerhardt H, Carmeliet P (2011) Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell 146: 873–887

Google Scholar - Potente M, Urbich C, Sasaki K, Hofmann WK, Heeschen C, Aicher A, Kollipara R, DePinho RA, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S (2005) Involvement of Foxo transcription factors in angiogenesis and postnatal neovascularization. J Clin Investig 115: 2382–2392

Google Scholar - Ren XD, Kiosses WB, Schwartz MA (1999) Regulation of the small GTP‐binding protein Rho by cell adhesion and the cytoskeleton. EMBO J 18: 578–585

Google Scholar - Rodgers JT, Vogel RO, Puigserver P (2011) Clk2 and B56beta mediate insulin‐regulated assembly of the PP2A phosphatase holoenzyme complex on Akt. Mol Cell 41: 471–479

Google Scholar - Roignot J, Soubeyran P (2009) ArgBP2 and the SoHo family of adapter proteins in oncogenic diseases. Cell Adhes Migr 3: 167–170

Google Scholar - Roman BL, Pham VN, Lawson ND, Kulik M, Childs S, Lekven AC, Garrity DM, Moon RT, Fishman MC, Lechleider RJ, Weinstein BM (2002) Disruption of acvrl1 increases endothelial cell number in zebrafish cranial vessels. Development 129: 3009–3019

Google Scholar - Sastry SK, Rajfur Z, Liu BP, Cote JF, Tremblay ML, Burridge K (2006) PTP‐PEST couples membrane protrusion and tail retraction via VAV2 and p190RhoGAP. J Biol Chem 281: 11627–11636

Google Scholar - Schmidt A, Wenzel D, Thorey I, Sasaki T, Hescheler J, Timpl R, Addicks K, Werner S, Fleischmann BK, Bloch W (2006) Endostatin influences endothelial morphology via the activated ERK1/2‐kinase endothelial morphology and signal transduction. Microvasc Res 71: 152–162

Google Scholar - Sents W, Ivanova E, Lambrecht C, Haesen D, Janssens V (2012) The biogenesis of active protein phosphatase 2A holoenzymes: a tightly regulated process creating phosphatase specificity. FEBS J 280: 644–661

Google Scholar - Sheehan KA, Ke Y, Solaro RJ (2007) p21‐Activated kinase‐1 and its role in integrated regulation of cardiac contractility. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Compar Physiol 293: R963–R973

Google Scholar - Song MH, Liu Y, Anderson DE, Jahng WJ, O'Connell KF (2011) Protein Phosphatase 2A‐SUR‐6/B55 regulates centriole duplication in C. elegans by controlling the levels of centriole assembly factors. Dev Cell 20: 563–571

Google Scholar - Sontag E, Nunbhakdi‐Craig V, Bloom GS, Mumby MC (1995) A novel pool of protein phosphatase 2A is associated with microtubules and is regulated during the cell cycle. J Cell Biol 128: 1131–1144

Google Scholar - Sontag E, Nunbhakdi‐Craig V, Lee G, Brandt R, Kamibayashi C, Kuret J, White CL 3rd, Mumby MC, Bloom GS (1999) Molecular interactions among protein phosphatase 2A, tau, and microtubules. Implications for the regulation of tau phosphorylation and the development of tauopathies. J Biol Chem 274: 25490–25498

Google Scholar - Soubeyran P, Barac A, Szymkiewicz I, Dikic I (2003) Cbl‐ArgBP2 complex mediates ubiquitination and degradation of c‐Abl. Biochem J 370: 29–34

Google Scholar - Stehbens S, Wittmann T (2012) Targeting and transport: How microtubules control focal adhesion dynamics. J Cell Biol 198: 481–489

Google Scholar - Strilic B, Kucera T, Eglinger J, Hughes MR, McNagny KM, Tsukita S, Dejana E, Ferrara N, Lammert E (2009) The molecular basis of vascular lumen formation in the developing mouse aorta. Dev Cell 17: 505–515

Google Scholar - Strilic B, Kucera T, Lammert E (2010) Formation of cardiovascular tubes in invertebrates and vertebrates. Cell Mol Life Sci 67: 3209–3218

Google Scholar - Tar K, Csortos C, Czikora I, Olah G, Ma SF, Wadgaonkar R, Gergely P, Garcia JG, Verin AD (2006) Role of protein phosphatase 2A in the regulation of endothelial cell cytoskeleton structure. J Cell Biochem 98: 931–953

Google Scholar - Traver D, Paw BH, Poss KD, Penberthy WT, Lin S, Zon LI (2003) Transplantation and in vivo imaging of multilineage engraftment in zebrafish bloodless mutants. Nat Immunol 4: 1238–1246

Google Scholar - Tsubouchi A, Sakakura J, Yagi R, Mazaki Y, Schaefer E, Yano H, Sabe H (2002) Localized suppression of RhoA activity by Tyr31/118‐phosphorylated paxillin in cell adhesion and migration. J Cell Biol 159: 673–683

Google Scholar - Virshup DM, Shenolikar S (2009) From promiscuity to precision: protein phosphatases get a makeover. Mol Cell 33: 537–545

Google Scholar - Wang P, Pinson X, Archambault V (2011) PP2A‐twins is antagonized by greatwall and collaborates with polo for cell cycle progression and centrosome attachment to nuclei in drosophila embryos. PLoS Genet 7: e1002227

Google Scholar - Wang Y, Kaiser MS, Larson JD, Nasevicius A, Clark KJ, Wadman SA, Roberg‐Perez SE, Ekker SC, Hackett PB, McGrail M, Essner JJ (2010) Moesin1 and Ve‐cadherin are required in endothelial cells during in vivo tubulogenesis. Development 137: 3119–3128

Google Scholar - Watanabe N, Kato T, Fujita A, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S (1999) Cooperation between mDia1 and ROCK in Rho‐induced actin reorganization. Nat Cell Biol 1: 136–143

Google Scholar - Wolfenson H, Henis YI, Geiger B, Bershadsky AD (2009) The heel and toe of the cell's foot: a multifaceted approach for understanding the structure and dynamics of focal adhesions. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 66: 1017–1029

Google Scholar - Xu K, Cleaver O (2011) Tubulogenesis during blood vessel formation. Semin Cell Dev Biol 22: 993–1004

Google Scholar - Yan L, Guo S, Brault M, Harmon J, Robertson RP, Hamid R, Stein R, Yang E (2012) The B55alpha‐containing PP2A holoenzyme dephosphorylates FOXO1 in islet beta‐cells under oxidative stress. Biochem J 444: 239–247

Google Scholar - Yan L, Mieulet V, Burgess D, Findlay GM, Sully K, Procter J, Goris J, Janssens V, Morrice NA, Lamb RF (2010) PP2A T61 epsilon is an inhibitor of MAP4K3 in nutrient signaling to mTOR. Mol Cell 37: 633–642

Google Scholar - Yan Z, Fedorov SA, Mumby MC, Williams RS (2000) PR48, a novel regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A, interacts with Cdc6 and modulates DNA replication in human cells. Mol Cell Biol 20: 1021–1029

Google Scholar - Zaidel‐Bar R, Milo R, Kam Z, Geiger B (2007) A paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation switch regulates the assembly and form of cell‐matrix adhesions. J Cell Sci 120: 137–148

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank members of the PSI laboratory for helpful and stimulating discussions. We also thank the GIGA‐Imaging and Zebrafish facilities for technical support. This research has been funded by the Interuniversity Attraction Poles Program initiated by the Belgian Science Policy Office (IUAP‐BELSPO PVI/28 and PVII/13) and was supported by the Belgian National Fund for Scientific Research. MM and NS are Post‐doctoral Researchers, FD, J‐CT, DM and CD are Research Associates, AB is an FRIA Fellow, and RK was a Research Director of the Belgian National Fund for Scientific Research. The work of MP is supported by the Max Planck Society, the German Research Foundation (SFB 834), the Cluster of Excellence Macromolecular Complexes (EXC115), the Excellence Cluster Cardiopulmonary System (EXC 147/1), the Foundation Leducq Transatlantic Network ARTEMIS and an European Research Council Starting Grant (ANGIOMET). HG is supported by Cancer Research UK, the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine, the Foundation Leducq Transatlantic Network ARTEMIS and an European Research Council Starting Grant (REshape, 311719). PC is supported by Methusalem funding—long‐term structural funding by the Flemish Government; Belgian Science Policy IUAP P7/03, Leducq Transatlantic Network ARTEMIS, ERC Advanced Grant.

Author contributions: MM and IG performed research and analysed data. JB and AB performed research. MP, ML, NS, CD, J‐CT, PS, PP, DM, VJ., W‐KH, PC and FC provided new reagents or analytic tools, RK gave conceptional and technological advice, HG and FD designed the study, and wrote the manuscript.

Author information

Author notes

- These authors contributed equally to this work.

- These authors contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

- Laboratory of Protein Signaling and Interactions, Interdisciplinary Cluster for Applied Genoproteomics (GIGA‐R), University of Liège, Sart‐Tilman, Belgium

Maud Martin, Jonathan Bruyr, Anouk Bleuart, Jean‐Claude Twizere, Richard Kettmann & Franck Dequiedt - Vascular Patterning Laboratory, VRC, VIB, Leuven, Belgium

Ilse Geudens & Holger Gerhardt - Department of Oncology, Vascular Patterning Laboratory, VRC, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Ilse Geudens & Holger Gerhardt - Max‐Planck‐Institute for Heart and Lung Research, Angiogenesis and Metabolism Laboratory, Bad Nauheim, Germany

Michael Potente - Department of Cardiology, Internal Medicine III, Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany

Michael Potente - Laboratory of Virology and Immunology, GIGA‐R, University of Liège, Sart‐Tilman, Belgium

Marielle Lebrun - Laboratoire de Bioinformatique des Génomes et des Réseaux (BiGRe), Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Bruxelles, Belgium

Nicolas Simonis - Laboratory of Connective Tissues Biology, GIGA‐Cancer, University of Liège, Sart‐Tilman, Belgium

Christophe Deroanne - CRCM, INSERM U1068; Institut Paoli‐Calmettes; Aix‐Marseille Université, UM105; CNRS, UMR7258, Marseille, France

Philippe Soubeyran - Metastasis Research Laboratory, GIGA‐Cancer, University of Liege, Liege, Belgium

Paul Peixoto & Denis Mottet - Laboratory of Protein Phosphorylation and Proteomics, Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Veerle Janssens - Department of Hematology and Oncology, University Hospital, Mannheim, Germany

Wolf‐Karsten Hofmann - Research Group Neural Circuit Development and Regeneration, Department of Biology, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (KU Leuven), Leuven, Belgium

Filip Claes - Laboratory of Angiogenesis and Neurovascular Link, VRC, VIB, Leuven, Belgium

Peter Carmeliet - Laboratory of Angiogenesis and Neurovascular Link, Department of Oncology, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Peter Carmeliet - Vascular Biology Laboratory, London Research Institute—Cancer Research UK, London, UK

Holger Gerhardt - Vascular Biology Laboratory, Cancer Research UK, 44 Lincoln's Inn Fields, London, WC2A 3LY, UK

Holger Gerhardt - Laboratory of Protein Signaling and Interactions, Interdisciplinary Cluster for Applied Genoproteomics (GIGA‐R), University of Liège, 1, Av de l'hopital, Liège 4000, Belgium

Franck Dequiedt

Authors

- Maud Martin

- Ilse Geudens

- Jonathan Bruyr

- Michael Potente

- Anouk Bleuart

- Marielle Lebrun

- Nicolas Simonis

- Christophe Deroanne

- Jean‐Claude Twizere

- Philippe Soubeyran

- Paul Peixoto

- Denis Mottet

- Veerle Janssens

- Wolf‐Karsten Hofmann

- Filip Claes

- Peter Carmeliet

- Richard Kettmann

- Holger Gerhardt

- Franck Dequiedt

Corresponding authors

Correspondence toHolger Gerhardt or Franck Dequiedt.

Ethics declarations

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Copyright: European Molecular Biology Organization

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, M., Geudens, I., Bruyr, J. et al. PP2A regulatory subunit Bα controls endothelial contractility and vessel lumen integrity via regulation of HDAC7.EMBO J 32, 2491–2503 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2013.187

- Received: 08 February 2013

- Accepted: 19 July 2013

- Published: 16 August 2013

- Issue date: 11 September 2013

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2013.187

Keywords

Profiles

- Philippe Soubeyran View author profile

- Veerle Janssens View author profile

- Franck Dequiedt View author profile