Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size (original) (raw)

Main

We first analysed the expression patterns of Bmpr1a (Alk3) and Bmpr1b (Alk6) in bone marrow and the surrounding bone tissue. BMPRIA was found in bone marrow cells, including most of the haematopoietic lineages apart from the HSC population, and most osteoblastic cells (Fig. 1a–c). By contrast, we were unable to detect expression of Bmpr1b in HSCs and the other haematopoietic lineages that we examined (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1: Expression patterns of BMPRIA and BMPRIB in bone and bone marrow.

a, Schematic of bone and bone marrow structures. TBA, trabecular bone area. b, Expression of BMPRIA in osteoblastic cells and bone marrow cells. Bone/bone marrow sections were immunohistochemically stained using anti-BMPRIA serum. TB, trabecular bone. c, Detection of Bmpr1a gene expression in HSCs and lineage cells by RT–PCR (polymerase chain reaction with reverse transcription) assay. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; B220, B-cell marker; Gr1Mac1, myeloid lineage markers; Ter119, erythroid lineage marker; CD41, megakaryocyte marker; DN, double negative for CD4 and CD8; DN1, CD44+CD25-; DN2, CD44+CD25+; DN3, CD44-CD25+; DN4, CD44-CD25-. d, Detection of Bmpr1b gene expression in HSCs and lineage cells by RT–PCR assay. NC, negative control.

To block the BMP signal, we inactivated BMPRIA by crossing Bmpr1a fx/fx and Bmpr1a fx/- mouse lines4 with a PolyI:C-inducible Mx1_–_Cre mouse line5 and assaying the mutant mice. Multiple injections of PolyI:C were required for efficient deletion of Bmpr1a (see Supplementary Information, data 1)

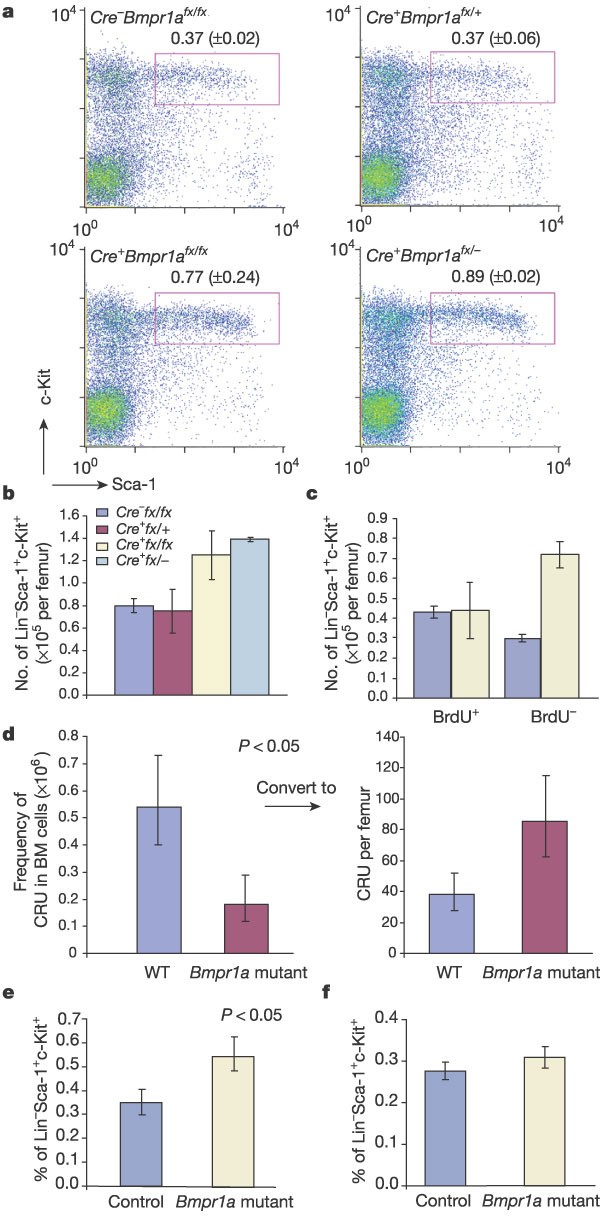

Mice with different injection schedules (see Methods) were investigated using flow cytometric assays to analyse the HSC population. The percentage of lineage-negative (Lin-) Sca-1+c-Kit+ (HSC) cells was increased 2-fold in the Mx1_–_Cre+Bmpr1a fx/fx and 2.4-fold in the Mx1_–_Cre+Bmpr1a fx/- mutant mice compared with the littermate controls (Fig. 2a). Although the total bone marrow cell number per femur was reduced in both of the Bmpr1a mutant lines owing to reduced cavity room, as seen in Fig. 3b, the absolute number of HSCs per femur was still increased 1.5–2-fold (Fig. 2b). As no significant difference between Mx1_–_Cre+Bmpr1a fx/fx and Mx1_–_Cre+Bmpr1a fx/- mutant mice was observed, we focused on the Mx1_–_Cre+Bmpr1a fx/fx mice in the following studies.

Figure 2: Analyses of the HSC population.

For raw data, see Supplementary Tables 1–4. a, Typical example of flow assay on the HSC population. Figure in the gate is the percentage of HSCs in the BM-MNC fraction. b, Comparison of absolute number of HSCs per femur in wild-type and Bmpr1a mutant mice. Owing to the reduced bone cavity in Bmpr1a mutant mice, the total bone marrow cell number is also reduced in mutant mice (an average of 1.58 × 107 versus 2.1 × 107 in wild-type control mice). The absolute HSC number is equal to the percentage of HSCs multiplied by the total number of BM-MNCs. c, Comparison of the number of LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs in the Bmpr1a mutant and control mice. d, CRU assay to compare the number of functional HSCs per femur between the Bmpr1a mutant and wild-type (WT) control mice. The number of CRUs per femur (right panel) equals the frequency of CRUs (left panel) multiplied by the total number of BM-MNCs as indicated in b. e–f, Bar graphs of the percentage of HSCs in recipient mice. Wild-type donor (Ly5.1) HSCs (2 × 103) were transplanted into Bmpr1a mutant recipients or littermate controls (Ly5.2) (e). Bone marrow cells (2 × 106) from controls and mutants (Ly5.2) were transplanted into wild-type recipients (Ly5.1) (f).

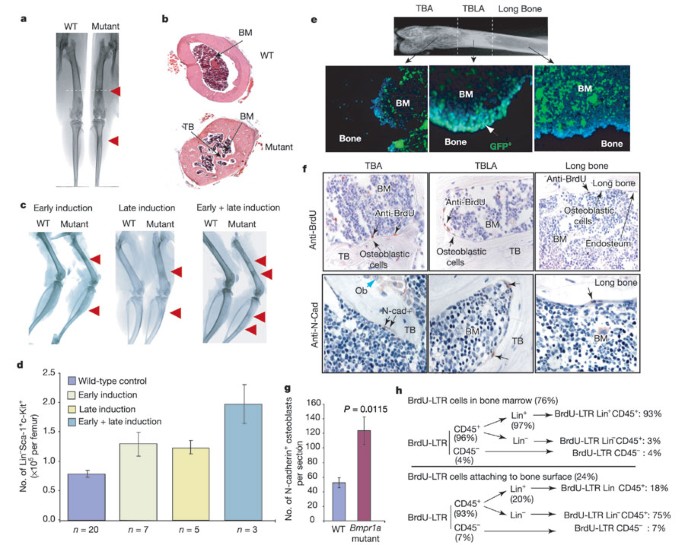

Figure 3: Analyses of bone structure and HSC number.

a, b, X-ray image and histology of the bone structures of ectopically formed TBLA (red arrow). BM, bone marrow. c, X-ray images of femur and tibia from Bmpr1a mutant and control mice. d, Comparison of the absolute number of HSCs per femur in Bmpr1a mutant and wild-type control mice. e, Inactivation of Bmpr1a on the surface of ectopically formed TBLA in the triple-genotype mice as shown by GFP expression, counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). f, BrdU-LTR cells (upper panels, black arrow), SNO cells (lower panels, black arrow) and matrix-forming osteoblasts (blue arrow). g, SNO cell number in control and Bmpr1a mutant mice. (The average total number of the SNO cells per section is given in Supplementary Table 6.) h, Summary of the distribution of three types of BrdU-LTR cell (see text and Supplementary Table 7).

The HSC population is a heterogeneous mixture, including long-term (LT) and short-term (ST) HSCs6. Therefore, we injected the mice with 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) to label cycling cells. Three hours after labelling, we analysed the HSC population to distinguish ST-HSCs from LT-HSCs according to differences in their cell-cycle state. The percentage of BrdU-negative cells in the HSC population (including the quiescent LT-HSCs) increased by an average of 2.4 times in the Bmpr1a mutant mice compared with littermate controls. The percentage of BrdU-positive cells in the HSC population (including the cycling ST-HSCs) was similar to that in the littermate controls (Fig. 2c). Therefore, direct comparison of the entire HSC population provides an underestimated but reliable representation (Fig. 2b; 1.6-fold) of the difference in LT-HSC numbers (Fig. 2c; 2.4-fold) between the mutant and control animals.

These experiments demonstrated an increase in the LT-HSC population. However, the gold-standard test for functional stem cells is the competitive repopulation unit (CRU) assay7, in which a series of diluted donor-derived bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) is transplanted into different groups of sublethally irradiated recipient mice. Three months after transplantation, peripheral blood is examined to monitor the engraftment of donor cells in the recipient mice in order to determine the lowest number of bone marrow cells required for the reconstitution of haematopoiesis. Using this assay, we confirmed that the functional stem cell number increased 2.2-fold in the mutant mice compared with controls (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 4). The results from both immunophenotypical and CRU assays indicate that the population of LT-HSCs is expanded in the Bmpr1a mutant mice.

There are several mechanisms that can lead to changes in the HSC number: (1) an intrinsic change in stem cells that either promotes self-renewal or blocks apoptosis; (2) an internal defect in progenitors that inhibits differentiation, leading to an accumulation of stem cells; or (3) an external influence from the HSC microenvironment. The finding that Bmpr1a is not expressed in HSCs (Fig. 1c) does not support the argument that an intrinsic defect in HSCs was the cause of a change in the number of HSCs in the Bmpr1a mutant mice. We then analysed myeloid and lymphoid lineages, common myeloid progenitor and common lymphoid progenitor subsets8,9. The results revealed no significant phenotypical change in any of the subsets analysed (Supplementary Information, data 2a, b). This was consistent with results obtained from in vitro colony-forming unit (CFU) assays, which showed that the progenitor number of different lineages was similar in the Bmpr1a mutant and littermate control mice (Supplementary Information, data 3). These results ruled out the possibility of an accumulation of HSCs resulting from a block in progenitor cell differentiation.

Direct evidence of an external influence causing the change in HSC number came from reciprocal bone marrow/HSC transplantation experiments. HSCs isolated from wild-type Ly5.1 mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated Bmpr1a mutant and littermate control mice (both Ly5.2 genotype). The result of a flow cytometric assay three months after transplantation revealed that the percentage of donor-derived HSCs in the Bmpr1a mutant mice was, on average, 1.6 times higher than in the wild-type control recipient mice (Fig. 2e). A reciprocal assay was also carried out by transplanting BM-MNCs derived from the Bmpr1a mutant or wild-type control mice into lethally irradiated wild-type Ly5.1 mice. These flow cytometric results showed that the percentage of donor-derived HSCs in both groups of recipient mice was similar, regardless of the origin of BM-MNCs (Fig. 2f). We conclude that the change in the microenvironment led to an increase in HSC number in the Bmpr1a mutant mice.

Bone marrow stromal cells are derived from mesenchymal stem cells, including fibroblasts, adipocytes, endothelial cells and osteoblasts10. Previous studies of the roles of stromal cells in supporting HSCs have been based mainly on in vitro culture, and each of these stromal cells has been suggested to be capable of supporting haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in vitro11,12. However, none of these results has been confirmed in vivo.

We observed obvious abnormal bone formation in the Bmpr1a mutant mice. Our X-ray and histological analyses revealed that an ectopic formation of trabecular-bone-like area (TBLA) occurred in the long-bone region of the mutant mice (Fig. 3a, b). The location of the ectopically formed TBLAs varied depending on the PolyI:C injection time: TBLAs were seen distal to the knee in the early-induced group, but were proximal to the knee in the late-induced group, and at both sites in the combined-injection group (Fig. 3c). This raised the possibility of a change in osteoblasts or osteoclasts affecting the HSC microenvironment. Recent in vitro evidence shows that an osteoblastic cell line can expand the number of HSCs 2–4-fold12. In addition, osteoblasts, when co-transplanted with HSCs, can also increase the engraftment rate13. These observations suggest that osteoblasts have a role in supporting HSCs.

We next asked whether the ectopically formed TBLA was responsible for the increased HSC number in the mutant mice. As described above (Fig. 2b), the number of HSCs per femur in the mutant animals was increased 1.67-fold on average in both early- and late-induced mutant mice. In addition, we found that the number of HSCs per femur increased 2.5-fold on average in the combined early- and late-induced mice, in which two regions of TBLA were observed (Fig. 3d). This shows that an increase in the number of HSCs correlates with an increase in the number of ectopically formed TBLAs.

We investigated the mechanism that leads to the ectopic formation of TBLA when the BMP signal is blocked. BMPRIA has been shown to inhibit osteoblastic lineage commitment from mesenchymal progenitors in vitro14. We ruled out the possibility of an increase in the number of mesenchymal progenitors in the mutants using a CFU-fibroblast assay10 (Supplementary Table 5). Osteoblastic lineage commitment from mesenchymal progenitors is not increased, because the ectopic formation of TBLA is regional rather than evenly distributed. This suggests that regional inactivation of Bmpr1a leads to the ectopic formation of TBLA. To confirm this, we generated a triple-genotype mouse line bearing Mx1_–_Cre, Bmpr1a fx/fx and Z/EG alleles. Cre-induced green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression reflects successful targeting of Bmpr1a (Fig. 3e). Analysis of bone sections derived from the triple-genotype mice revealed that only the surface of ectopically formed TBLA was GFP positive, indicating that regional deletion of Bmpr1a occurs exclusively in the cells that line the TBLA surface. This was further supported by a 3-fold increase in osteoblast number, a 2-fold increase in the rate of bone formation, and a 10-fold increase in bone volume in the TBLA of Bmpr1a mutants compared with the long-bone region in control littermates (Supplementary Information, data 4, and Supplementary Table 8); however, there was no apparent change in osteoclasts (cells that reabsorb bone) measured by tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase staining (data not shown). The ectopic TBLA might be formed by over-proliferation or abnormal differentiation of an osteoblast progenitor. In addition, inactivation of BMPRIA might make the osteoblasts less sensitive to apoptotic signal, as a BMP signal is known to induce osteoblast apoptosis15.

We observed a correlation between the number of LT-HSCs and the increase in TBLA. Are the LT-HSCs in the TBLA enriched? The limited number of LT-HSCs in bone marrow and the lack of a unique marker make their visualization difficult. As LT-HSCs are quiescent or slow cycling, they are able to retain labelled nucleotides for a relatively long period and can be identified as BrdU-LTR (long-term retaining) cells16 (see Methods). We found that 76% of the BrdU-LTR cells were located within the bone marrow cavity, whereas 24% were attached to the bone surface. Most BrdU-LTR cells attached to the bone surface were located in cancellous/trabecular bone area (including epiphysis and metaphysis), whereas the rest were dispersed along the endosteal surface of long bone (Fig. 3f, upper panel). This is consistent with previous observations in which HSCs were found to be close to the endosteal surface of long bone17 or homing to the bone surface of epiphysis18. Importantly, a significantly increased number of BrdU-LTR cells was found in the ectopically formed TBLA compared with the long-bone region (Fig. 3f). There are different types of BrdU-LTR cell, including Lin-CD45+ (enriched with LT-HSCs), Lin+CD45+ (enriched with memory T or B cells) and Lin-CD45- (enriched with mesenchymal stem cells) (see Fig. 3h). We estimate that the frequency of the enriched LT-HSCs in control animals (BrdU-LTR Lin-CD45+ cells) is 0.01%, close to the frequency of LT-HSCs (0.007%) on the basis of functional studies19. These cells are located mainly on the bone surface, particularly the surface of the cancellous/trabecular bone, and most of these cells are co-stained with other HSC markers: CD45, Sca-1 and c-Kit (Fig. 4a–c). These observations support the conclusion that the ectopically formed TBLA is responsible for the increase in the number of HSCs.

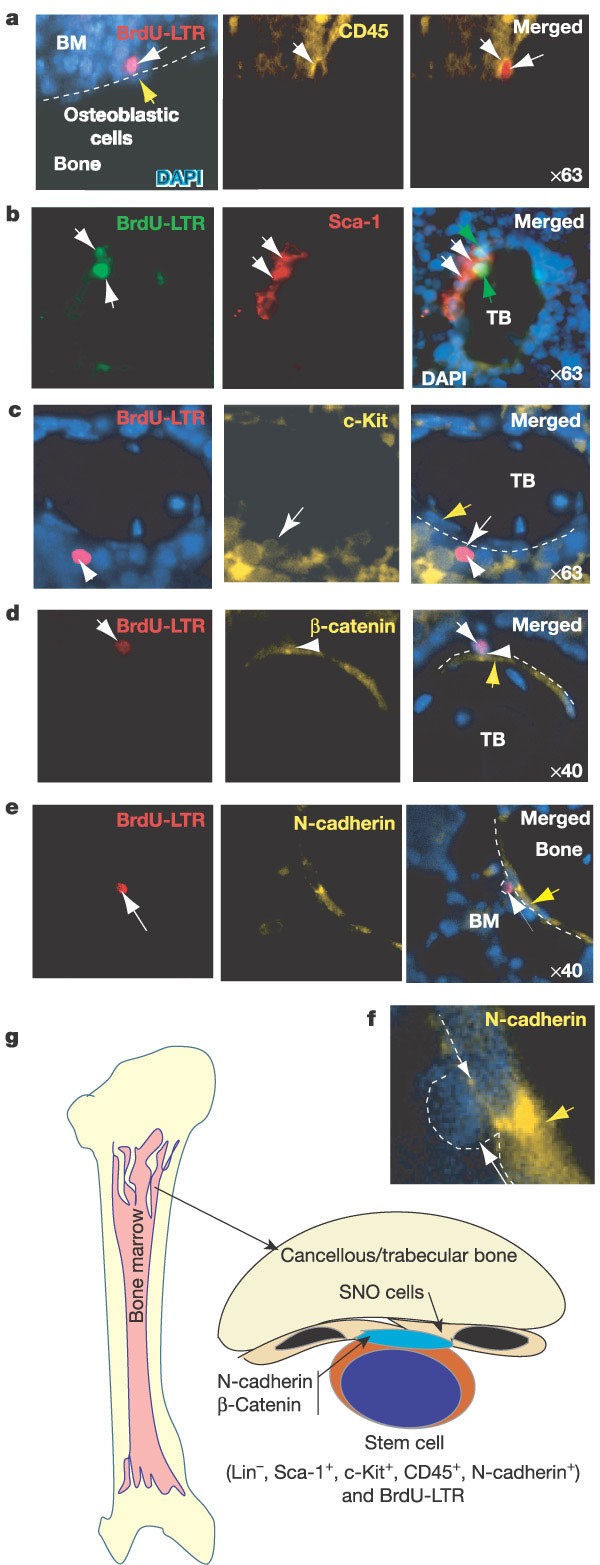

Figure 4: Co-staining of BrdU-LTR cells with HSC markers, counterstained with DAPI.

a–e, HSC markers as indicated. The lens magnification used for the microscopic photograph is indicated. Most BrdU-LTR cells attached to the trabecular bone surface are co-stained with Sca-1 (74%), c-Kit (72%) or a pan-haematopoietic marker, CD45 (92%). Yellow arrow indicates SNO cells. f, A blow-up of part e. g, Model illustrating the haematopoietic stem cell niche. The SNO cells, which are located mainly on the surface of cancellous/trabecular bone, are a key component of the resident niche for HSCs.

The increased number of osteoblasts on the surface of ectopically formed TBLA correlates with the increase in HSC number. The LT-HSCs appear to be attached to cells with an early osteoblastic character (the mononuclear spindle-shaped cells lining the bone surface; Fig. 3f, upper panel). As N-cadherin is expressed in both early and late osteoblastic cells20, we used this biological marker to confirm this observation. This marker stains two osteoblastic cell types: a small subset of spindle-shaped osteoblasts (osteoblastic lining cells) and most of the larger, oval-shaped, matrix-forming osteoblasts (Fig. 3f, lower panel). Histological analysis of the distribution of the spindle-shaped N-cadherin+ osteoblastic (SNO) cells revealed that these cells were enriched on the surface of cancellous/trabecular bone, including the vesicle area in epiphysis, and sporadically dispersed along the endosteal surface of long bone (Fig. 3f, lower panel). This distribution pattern was similar to that of LT-HSCs (Fig. 3f, upper panel). Indeed, the LT-HSCs are attached only to the SNO cells that line the bone surface, (Fig. 4e). We also counted the number of SNO cells (Supplementary Table 6). The result showed that an increase in the number of these cells (2.3-fold; Fig. 3g) correlates to a high degree with the increase in LT-HSC number (2.2-fold; Fig. 2d) in the Bmpr1a mutant mice. Taken together, these observations indicate that the SNO cells have an important role in supporting LT-HSCs. This conclusion is also supported by evidence from studies of conditional ablation of osteoblasts in Col2.3Δtk (thymidine kinase) transgenic mice, which showed that osteoblasts were necessary for the maintenance of haematopoiesis and where a loss of osteoblasts led to loss of haematopoietic cells21.

As the functions of the niche include adhesive interaction between stem cells and the niche22, we asked whether the SNO cells provide an adhesive attachment for HSCs. In Drosophila, two important junction-related adherens molecules, E-cadherin and β-catenin, are essential for the maintenance of ovarian somatic stem cells, as evidenced by the observation that a loss of E-cadherin leads to a loss of somatic stem cells23. E-cadherin was not expressed in either the osteoblasts or the LT-HSCs (although it was expressed in many bone marrow cells; data not shown). However, we found that N-cadherin was asymmetrically localized to the cell surface of LT-HSCs adjacent to the SNO cells (Fig. 4e, f). Using flow cytometric assay, we confirmed that N-cadherin is expressed in a subpopulation (10%) of murine adult HSCs (Lin-Sca-1+c-Kit+) (Supplementary Information, data 5). It will be important to demonstrate an in vivo functional role of the N-cadherin+ HSCs. In addition, β-catenin, which interacts with and forms an adherens complex with N-cadherin24, is also found to be asymmetrically localized between the SNO cells and the LT-HSCs (Fig. 4d).

The niche hypothesis was first proposed by Schofield25 in 1978, and is supported by the co-culture of HSCs with marrow stromal cells26. The stem cell niche has been described in the Drosophila ovary27, but the HSC niche, owing to complicated anatomical architecture, has remained an enigma. We show that, in bone and bone marrow, the cancellous/trabecular bone area is the primary site for HSCs. The SNO cells located on the bone surface are a key component of the niche, supporting LT-HSCs (Fig. 4g). SNO cells might support HSCs through a specific adhesive interaction between N-cadherin and β-catenin. Consistent with this, in col1-PPR (parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTHrP receptor) transgenic mice, the osteoblastic lineage has been defined as a key participant in the regulation of HSC numbers28. The niche size must be tightly regulated in vivo to maintain HSCs and normal homeostasis25,29. We provide in vivo evidence to show that a change in the niche size affects the number of stem cells. BMP signalling through BMPRIA is an important component of this regulatory system.

Methods

Inducible Cre expression

PolyI:C (250 µg per mouse) was injected intraperitoneally. For the early-induced group, PolyI:C was injected on the 3rd, 5th and 7th day after birth, whereas the late-induced group was treated with PolyI:C on the 21st, 23rd and 25th day after birth. A third double-induced group combined both injection schedules.

Flow cytometric assay and CFU culture

Isolation and preparation of bone marrow, thymus, spleen and peripheral blood cells, and the method for subsequent flow cytometric assays have been described30. For HSC analysis, BM-MNCs were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-lineage markers (CD4, CD8, CD3, B220, IgM, Mac-1, Gr-1 and Ter-119) to eliminate Lin+ cells, but positive for APC-c-Kit and phycoerythrin (PE)-Sca-1. For lineage analyses, see Supplementary Information, data 1a, b. CFU assay was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations (StemCell Technologies).

CRU assay

A series of diluted BM-MNCs (1 × 104, 3 × 104, 1 × 105 and 3 × 105) from either Bmpr1a mutant or wild-type control were transplanted into several groups of sublethally (500 rad) irradiated Ly5.1 recipient female mice. Three months after transplantation, peripheral blood was analysed using myeloid and lymphoid lineage markers: Mac-1, Gr-1, B220, CD3 and Ly5.2. An engraftment rate of >1% (the basal level was defined by transplantation of bone marrow derived from Ly5.1 mice) was scored as positive. The data shown in Fig. 2f are based on two independent experiments. The CRU frequencies were determined using L-Calc software (StemCell Technologies), which uses Poisson statistics and the method of maximum likelihood to the proportion of negative recipients, using limiting-dilution analysis (see Supplementary Table 4). We found that the CRU frequency was lower than that reported in studies where lethal doses of irradiation have been used7.

Immunohistochemistry and BrdU-LTR assay

The procedures for bone and bone marrow section preparation, immunostaining conditions and antibodies are described in Supplementary Methods. The procedure for BrdU pulse labeling, LTR and subsequent detection has been reported16. The mice were fed BrdU (0.8 mg ml-1 in water) for 10 days, during which time 40% of LT-HSCs would divide at least once31. Seventy days after BrdU labelling, sections were stained with anti-BrdU antibody.

N-cadherin+ cell count

For quantitative analysis of N-cadherin+ cells, the sections were developed with AEC after being incubated with rabbit anti-N-cadherin antibody for 1 h and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit second antibody for 1 h. Three people counted the SNO cells in these sections, blind to the source of the sections.

X-ray image

High-resolution X-rays (Faxitron MX-20) of bone and bone histomorphometry (OsteoMetrics, Inc.) were performed at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Dentistry.

References

- Spangrude, G. J., Heimfeld, S. & Weissman, I. L. Purification and characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Science 241, 58–62 (1988)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Maeno, M. et al. The role of BMP-4 and GATA-2 in the induction and differentiation of hematopoietic mesoderm in Xenopus laevis. Blood 88, 1965–1972 (1996)

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Davidson, A. J. & Zon, L. I. Turning mesoderm into blood: the formation of hematopoietic stem cells during embryogenesis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 50, 45–60 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Mishina, Y., Hanks, M. C., Miura, S., Tallquist, M. D. & Behringer, R. R. Generation of Bmpr/Alk3 conditional knockout mice. Genesis 32, 69–72 (2002)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kuhn, R., Schwenk, F., Aguet, M. & Rajewsky, K. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science 269, 1427–1429 (1995)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Morrison, S. J. & Weissman, I. L. The long-term repopulating subset of hematopoietic stem cells is deterministic and isolatable by phenotype. Immunity 1, 661–673 (1994)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Szilvassy, S., Nicolini, F. E., Eaves, C. J. & Miller, C. L. in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Protocols (eds Klug, C. A. & Jordan, C. T.) 167–187 (Humana Press, Totowa, New Jersey, 2002)

Google Scholar - Kondo, M., Weissman, I. L. & Akashi, K. Identification of clonogenic common lymphoid progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Cell 91, 661–672 (1997)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Akashi, K., Traver, D., Miyamoto, T. & Weissman, I. L. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature 404, 193–197 (2000)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Simmons, P., Gronthos, S. & Zannettino, A. C. in Hematopoiesis: A Developmental Approach (ed. Zon, L. I.) 718–726 (Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 2001)

Google Scholar - Charbord, P. The hematopoietic stem cell and the stromal microenvironment. Therapie 56, 383–384 (2001)

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Taichman, R. S., Reilly, M. J. & Emerson, S. G. The hematopoietic microenvironment: osteoblasts and the hematopoietic microenvironment. Hematology 4, 421–426 (2000)

Article Google Scholar - El-Badri, N. S., Wang, B. Y. & Cherry Good, R. A. Osteoblasts promote engraftment of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells. Exp. Hematol. 26, 110–116 (1998)

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chen, D. et al. Differential roles for bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) receptor type IB and IA in differentiation and specification of mesenchymal precursor cells to osteoblast and adipocyte lineages. J. Cell Biol. 142, 295–305 (1998)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hay, E., Lemonnier, J., Fromigue, O. & Marie, P. J. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 promotes osteoblast apoptosis through a Smad-independent, protein kinase C-dependent signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29028–29036 (2001)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Taylor, G., Lehrer, M. S., Jensen, P. J., Sun, T. T. & Lavker, R. M. Involvement of follicular stem cells in forming not only the follicle but also the epidermis. Cell 102, 451–461 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Nilsson, S. K., Johnston, H. M. & Coverdale, J. A. Spatial localization of transplanted hemopoietic stem cells: inferences for the localization of stem cell niches. Blood 97, 2293–2299 (2001)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Askenasy, N. & Farkas, D. L. Optical imaging of PKH-labeled hematopoietic cells in recipient bone marrow in vivo. Stem Cells 20, 501–513 (2002)

Article Google Scholar - Lagasse, E., Shizuru, J. A., Uchida, N., Tsukamoto, A. & Weissman, I. L. Toward regenerative medicine. Immunity 14, 425–436 (2001)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hay, E. et al. N- and E-cadherin mediate early human calvaria osteoblast differentiation promoted by bone morphogenetic protein-2. J. Cell. Physiol. 183, 117–128 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Visnjic, D. et al. Conditional ablation of the osteoblast lineage in Col2.3Δtk transgenic mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 16, 2222–2231 (2001)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Spradling, A., Drummond-Barbosa, D. & Kai, T. Stem cells find their niche. Nature 414, 98–104 (2001)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Song, X. & Xie, T. DE-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion is essential for maintaining somatic stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14813–14818 (2002)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Puch, S. et al. N-cadherin is developmentally regulated and functionally involved in early hematopoietic cell differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 114, 1567–1577 (2001)

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Schofield, R. The relathionship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haematopoietic stem cell. A hypothesis. Blood Cells 4, 7–25 (1978)

CAS Google Scholar - Dexter, T. M., Allen, T. D. & Lajtha, L. G. Conditions controlling the proliferation of haemopoietic stem cells in vitro. J. Cell. Physiol. 91, 335–344 (1977)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Xie, T. & Spradling, A. C. A niche maintaining germ line stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Science 290, 328–330 (2000)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Calvi, L. M. et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature 425, 841–846 (2003)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Weissman, I. L. Developmental switches in the immune system. Cell 76, 207–218 (1994)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Akashi, K. et al. Transcriptional accessibility for genes of multiple tissues and hematopoietic lineages is hierarchically controlled during early hematopoiesis. Blood 101, 383–389 (2003)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Cheshier, S. H., Morrison, S. J., Liao, X. & Weissman, I. L. In vivo proliferation and cell cycle kinetics of long-term self-renewing hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3120–3125 (1999)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank P. Dijke for providing anti-BMPR1A anti-serum, and C. G. Lobe for Z/EG reporter mice. We thank R. Krumlauf and X. Liao for scientific discussion. We thank H. Lin for critically reviewing the manuscript, and L. Bonewald for training in bone histomorphometry. We are grateful to D. di Natale and T. Langner for assistance in manuscript editing. We are grateful to S. Morris and D. Stark for imaging assistance, W. Walker and her co-workers for animal care, and C. Sonnenbrot and his co-workers for assistance in medium preparation. This work was supported by the Stowers Institute for Medical Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Stowers Institute for Medical Research, Kansas City, Missouri, 64110, USA

Jiwang Zhang, Chao Niu, Xi He, Wei-Gang Tong, Jason Ross, Jeff Haug, Teri Johnson, Leanne M. Wiedemann & Linheng Li - Department of Oral Biology, School of Dentistry, University of Missouri–Kansas City, 650 East 25th Street, Kansas City, Missouri, 64108, USA

Ling Ye, Haiyang Huang, Jian Q. Feng & Stephen Harris - Laboratory of Reproductive and Developmental Toxicology, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, 27709, USA

Yuji Mishina - Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Kansas University Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas, 66160, USA

Leanne M. Wiedemann & Linheng Li

Authors

- Jiwang Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Chao Niu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ling Ye

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Haiyang Huang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xi He

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Wei-Gang Tong

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jason Ross

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jeff Haug

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Teri Johnson

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jian Q. Feng

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Stephen Harris

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Leanne M. Wiedemann

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yuji Mishina

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Linheng Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence toLinheng Li.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Niu, C., Ye, L. et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size.Nature 425, 836–841 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02041

- Received: 12 May 2003

- Accepted: 12 August 2003

- Issue Date: 23 October 2003

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02041