V1 spinal neurons regulate the speed of vertebrate locomotor outputs (original) (raw)

Main

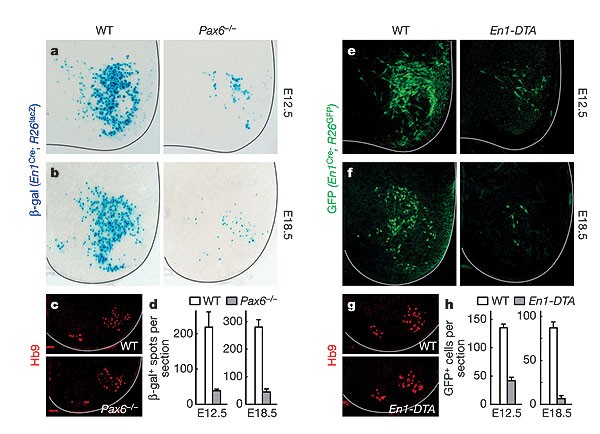

Several genetically defined classes of neurons have been identified in the developing spinal cord7, including a class of ipsilaterally projecting inhibitory neurons that innervate motor neurons, the Engrailed1 (En1)-expressing V1 neurons8,9,10,11. To assess the function of V1 neurons in the locomotor CPG, we used two mouse models that have selective loss of the En1-expressing V1 neuronal population (Fig. 1). This was achieved through the altered specification of V1 neurons in _Pax6_-knockout (_Pax6_-/-) mice and by the selective ablation of these neurons in _En1_Cre; _R26_-_lacZ_flox/DTA (_En1_-DTA; ref. 12) mice. At embryonic day (E)12.5, a marked reduction in En1-positive V1 neuron cell numbers was apparent in spinal cords isolated from _Pax6_-/- and _En1_-DTA embryos (Fig. 1a, e). This was confirmed using an _En1_Cre lacZ or green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter system9, which also showed that significantly fewer En1-derived V1 neurons are present at E18.5 (Fig. 1b, f). Both _Pax6_-/- and _En1_-DTA mice had normal numbers of lumbar spinal motor neurons that were appropriately organized into lateral and medial motor columns. (Fig. 1c, g). Spinal cords from _Pax6_-/- mice did show an increase in commissural V0 and V3 interneuron cell numbers, coupled with a slight decrease in ipsilaterally projecting Chx10-positive V2 neurons13 (Chx10 is a marker of V2 neurons; Supplementary Fig. S1). However, there were no changes in ventral interneuron specification in the _En1_-DTA mice (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 1: V1 neurons are reduced in _Pax6_-/- and _En1_-DTA spinal cords.

a, b, Cross-sections through E12.5 (a) and E18.5 (b) wild-type (WT) and _Pax6_-/- spinal cords, showing fewer En1-positive V1 neurons in the _Pax6_-/- spinal cord. V1 neurons were marked using _En1_Cre; _R26_lacZ reporter alleles. c, Lumbar-level Hb9 staining of motor neurons is largely unaffected in _Pax6_-/- embryos. d, Quantification of V1 neuron loss in the _Pax6_-/- spinal cord. e, f, _En1_-DTA embryos show a selective loss of En1-positive V1 neurons at E12.5 (e) and E18.5 (f). g, Numbers of Hb9-positive motor neurons and columnar organization are normal in the En1-DTA spinal cord. h, Quantification of V1 neuron loss in the _En1_-DTA cord. Error bars indicate s.d.

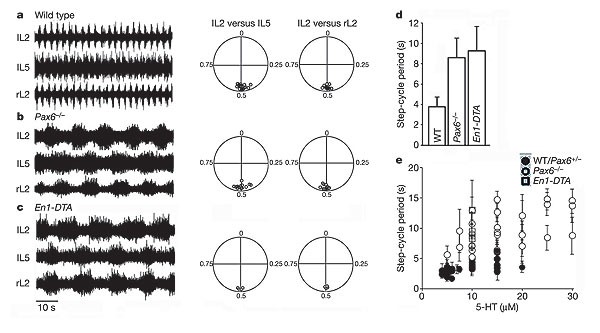

Limbed walking movements in vertebrates are characterized by the repetitive oscillatory bursting of motor neurons, in which flexor–extensor and left–right motor activities alternate. These locomotor-like oscillations can be induced in the isolated spinal cord by excitatory neurotransmitter agonists, and typically show a step-cycle period of 2–4 s (refs 5, 14, 15 and Fig. 2a). We asked whether V1 neurons regulate the coordination of flexor–extensor motor neurons during locomotion, because many V1 neurons differentiate into Renshaw cells and Ia inhibitory interneurons, two inhibitory cell types that have been proposed to coordinate flexor and extensor muscle activity around ipsilateral limb joints9,16,17,18,19. Spinal cords lacking V1 neurons showed a normal pattern of alternating flexor (L2) activity and extensor (L5) activity (Fig. 2a–c). Left–right alternation (that, is lL2 versus rL2) was also normal. However, ‘locomoting’ _Pax6_-/- and En1-DTA spinal cords did show a significant lengthening of both the step-cycle period and motor neuron burst duration (Fig. 2b–e).

Figure 2: Mice lacking V1 neurons show slow locomotor-like activity.

a–c, Left, electroneurograms from left (lL2) and right (rL2) L2 and left L5 (lL5) ventral roots after application of 5 µM NMDA and 10 µM 5-HT, showing locomotor-like activity in E18.5 spinal cords from wild-type (a), _Pax6_-/- (b) and _En1_-DTA (c) mice. Right, circular plots showing the coupling of bursts in lL5 and rL2 with respect to lL2. Each point represents the vector point for one experiment. d, Mean step-cycle period in wild-type, _Pax6_-/- and _En1_-DTA spinal cords. e, Plot of step-cycle period versus 5-HT concentration for _Pax6_-/- (open circles), _En1_-DTA (open squares) and wild-type/Pax6+/- spinal cords (filled circles). Error bars indicate s.d.

Whereas 5 µM NMDA (_N_-methyl-d-aspartate) in combination with 5 µM serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT) typically induces robust locomotor-like activity in wild-type spinal cords15 (Fig. 2a), we were only able to elicit a stable pattern of locomotor-like activity in _Pax6_-/- spinal cords by increasing the concentration of 5-HT to 7.5–20 µM (Fig. 2b, e). In experiments using 10 µM 5-HT, the step-cycle period (8.4 ± 2.9 s, mean ± s.d.) and burst duration (4.4 ± 1.0 s) in _Pax6_-/- spinal cords (n = 7) were increased significantly (P < 0.001, Student's _t_-test) compared to wild-type and heterozygous (Pax6+/-) spinal cords (step-cycle period 3.8 ± 0.8 s, burst duration 1.7 ± 0.8 s; n = 10). This relative increase in the step-cycle period was seen over a wide range of 5-HT concentrations (Fig. 2e). Similar lengthening of the step cycle (Fig. 2c, d) and burst duration was seen in _En1_-DTA mice (9.3 ± 2.3 s and 5.4 ± 1.1 s, respectively; n = 5 spinal cords; P < 0.001, _t_-test). V1 neurons are therefore dispensable for flexor–extensor coordination, but have an essential role in determining the speed of the locomotor rhythm.

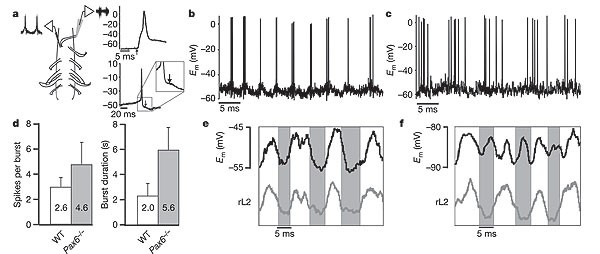

Current-clamp recordings of motor neurons in wild-type and _Pax6_-/- spinal cords (Fig. 3a–d) revealed that _Pax6_-/- motor neurons show prolonged periods of membrane potential depolarization, and that they continue to fire action potentials throughout this depolarized phase (Fig. 3c). This is consistent with flexor- and extensor-related CPG neurons remaining active for longer periods of time. These intracellular recordings also revealed that the alternating excitatory and inhibitory drive that normally underlies rhythmic changes in motor neuron membrane potential20 is still present in the _Pax6_-/- spinal cord (Fig. 3e). Importantly, _Pax6_-/- motor neurons still receive the phasic inhibitory inputs that are essential for coordinating alternating flexor and extensor activity (Fig. 3f). The origin of these phasic inhibitory inputs is not known—although they could in principle be derived from contralateral commissural interneurons21,22, this seems not to be the case, as ipsilateral locomotor coordination is normal in the _Pax6_-/- cord after spinal cord hemisection (data not shown).

Figure 3: Motor neuron firing during locomotion in the Pax6 -/- spinal cord is prolonged and shows rhythmic inhibition.

a, Schematic of recording setup, with a suction electrode recording electroneurogram activity from rL2 ventral root and an intracellular electrode recording from a motor neuron located in L2. Motor neurons were identified by the presence of an antidromic action potential in response to ventral root simulation (upper right panel, arrow) and by a small after-depolarization following orthodromic spikes (lower right panel, arrow), which is unique to rodent motor neurons. b, c, Recording from motor neurons located in rL2 of wild-type (b) and _Pax6_-/- (c) mice after application of NMDA and 5-HT. d, Chart showing the mean number of action potentials (mean ± s.d.) fired per depolarization of the motor neuron and the mean duration of the depolarized phase (LDP) of the motor neuron during locomotion in wild-type and _Pax6_-/-. e, f, Intracellular recording from a motor neuron located in the rL2 segment (upper traces) and electroneurogram recording from the rL2 ventral root (lower traces, rectified and integrated) in a _Pax6_-/- mouse. Grey area indicate the period during which rL2 is inactive. In e, recordings were performed at resting membrane potential (_E_m -50 mV) after application of 5 µM NMDA + 15 µM 5-HT. The motor neuron is active in-phase with ventral root activity. In f, the motor neuron is hyperpolarized to -88 mV, beyond the calculated Cl- reversal potential, which results in the emergence of out-of-phase depolarization owing to reversed inhibitory currents.

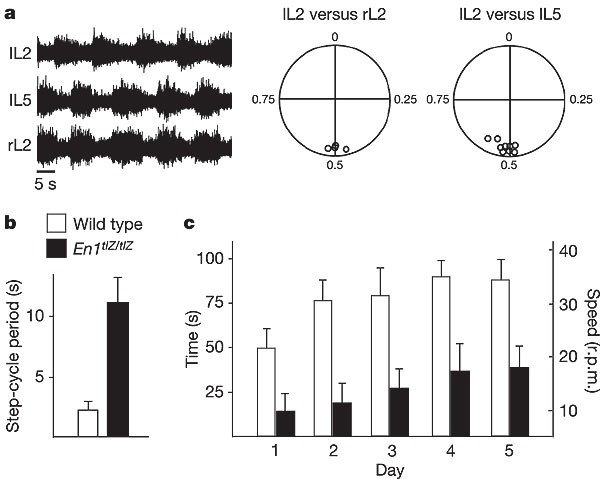

We then used En1 tlZ/tlZ null ‘knock-in’ mice (see ref. 8) to address the function of V1 neurons in the intact animal. Spinal cords isolated from E18.5 En1 tlZ/tlZ mice show a 3–4-fold slowing of the locomotor step cycle and lengthening of the burst duration (Fig. 4a, b; 11.2 ± 2.3 s and 6.1 ± 1.8 s, respectively; n = 10 spinal cords), which closely resemble the behavioural changes seen in _Pax6_-/- and _En1_-DTA spinal cords (compare with Fig. 2). Using a Wnt1 En1 transgene23 to rescue the En1 mutant midbrain–hindbrain phenotype, we obtained adult En1 tlZ/tlZ mice in which the V1 neuron connectivity defects in the spinal cords8,9 are not rescued (H.S., unpublished observation). When rotarod tests were performed on 4–6-month-old En1 tlZ/tlZ; Wnt1 En1 mice and age-matched controls, En1 tlZ/tlZ; Wnt1 En1 mice showed a clear deficit in their ability to walk and maintain their balance at higher rotarod speeds (Fig. 4c; see Methods). Although the duration (and the speed) for which the mutant animals walked on the rotarod increased during the trial period, at no time did they attain walking speeds above 18 r.p.m. However, these animals did walk on the rotarod for extended periods of times at idling speed (5 r.p.m., data not shown). In contrast, wild-type animals walked and maintained their balance at much higher speeds (approximately 22 r.p.m. on day 1 and up to 35 r.p.m. on day 5). This suggests that adult En1 mutants are impaired in their ability to perform quick stepping movements.

Figure 4: En1 tlZ/tlZ mice show a slowing of stepping movements.

a, Left, electroneurogram recordings from lL2, lL5 and rL2 ventral roots after application of 5 µM NMDA/7.5 µM 5-HT to an isolated E18.5 En1 tlZ/tlZ spinal cord. Right, circular plots indicate normal ventral root alternation. Each small circle corresponds to the vector point for a single experiment. b, Graph showing the increase in the step-cycle period in En1 tlZ/tlZ mutants compared with wild-type spinal cords. c, Rotarod testing of mouse motor behaviours, showing the time and bar speed that age-matched wild-type (open bars) and En1 tlZ/tlZ; Wnt1 En1 mice (filled bars; three animals each) were able to run on an accelerating rotarod. Error bars in b, c show s.d.

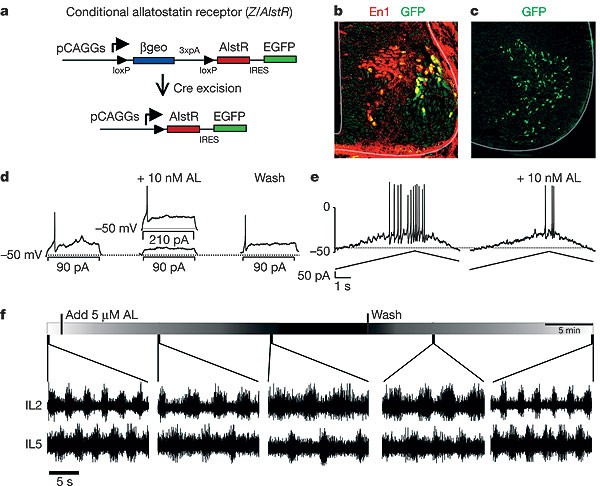

Next, we used transgenic mice (AlstR192 mice) that conditionally express the Drosophila allatostatin G-protein-coupled receptor (AlstR) to test whether acutely suppressing V1 neuron excitability causes a similar lengthening of the locomotor step cycle (Fig. 5a). AlstR couples to endogenous mammalian GIRK channels (inward-rectifying K+ channels), causing a decrease in cellular input resistance and neuronal excitability24. In control experiments, allatostatin (100 nM–5 µM) had no effect on motor rhythm generation, locomotor coordination or the step-cycle period (Supplementary Fig. S2a). In contrast, spinal cords from _nestin_Cre; AlstR192 mice showed strong allatostatin-dependent depression in rhythmic motor activity (Supplementary Fig. S2b).

Figure 5: Acute silencing of V1 neurons via the allatostatin receptor causes a slowing of locomotor-like rhythmicity.

a, Schematic showing the allatostatin receptor (Z/AlstR) transgene. Crossing mice that harbour this transgene with an _En1_Cre mouse excises the _loxP_-flanked β-geo sequences, leading to transcription of AlstR in En1-derived cells. b, Co-expression of GFP (green) and En1 (red) in an E11.5 _En1_Cre; AlstR192 mouse, showing V1 cells expressing AlstR. Many newborn V1 neurons in the subventricular zone are AlstR/GFP-negative owing to a delay in En1-dependent Cre removal of the stop cassette. c, Spinal cord slice from a P0 _En1_Cre; AlstR192 mouse carrying the ZnG reporter allele, showing GFP expression in V1 neurons. d, Recording from a V1 neuron expressing AlstR in a P1 _En1_Cre; AlstR192; ZnG mouse in response to current steps. e, Recordings from an AlstR-expressing V1 neuron in response to a current ramp. Before allatostatin (AL) application, the cell begins to fire upon current injection of 105 pA. After allatostatin application (10 nM), the cell only fires when the injected current reaches 190 pA. f, Electroneurogram recordings from lL2 and lL5 ventral roots in a P1 _En1_Cre; AlstR192 mouse, showing the effects of allatostatin (5 µM) application and wash-out on locomotor activity in the isolated spinal cord. The lengthening of the step cycle after allatostatin application was significant (P = 0.02, paired _t_-test; n = 15 spinal cords).

_En1_Cre; AlstR192 mice were then used to selectively express AlstR in V1 neurons (Fig. 5a, b). In spinal cord slices prepared from _En1_Cre; AlstR192 mice, we observed a pattern of GFP reporter expression that was identical to the normal distribution of V1 neurons (Fig. 5c). Whole-cell recordings from identified GFP-positive V1 neurons (n = 7 cells) revealed a reversible decrease in neuronal excitability in response to current steps (Fig. 5d) and ramps (Fig. 5e) after the addition of allatostatin (10 nM). The decrease in excitability (2–3-fold), although not as pronounced as in isolated adult neurons24, was nevertheless substantial, and it was not seen in control, AlstR-negative neurons (Supplementary Fig. S2c).

When locomotor-like activity was induced in postnatal day P0–P2 _En1_Cre; AlstR192 spinal cords (5 µM NMDA + 10 µM 5-HT; Fig. 5f), we observed a step-cycle period of 3–4 s (3.3 ± 0.8 s, n = 15 spinal cords), comparable to that seen in wild-type animals of a similar age. Application of allatostatin (1–5 µM) to these spinal cords resulted in marked and significant lengthening of the step-cycle period (7.9 ± 1.8 s, n = 15 spinal cords; P = 0.002, paired _t_-test), which was reversed upon washing out the neuropeptide (Fig. 5f). As such, lengthening of the locomotor step cycle that results from the defects in V1 neuron development can be reproduced when V1 neuronal activity is suppressed. Two recent studies have provided evidence that modifying neuronal activity during development can alter the neurotransmitter phenotype of spinal neurons25 and produce small changes in CPG motor outputs26, indicating that activity may have a role in organizing these locomotor networks However, our results show that the changes in locomotor CPG outputs following the acute suppression of V1 neurons compared with the early loss of V1 neurons are highly concordant. This suggests that the absence of V1 neurons during development does not markedly reconfigure the spinal locomotor CPG network.

Our findings outline an essential role for V1 neurons in mammals in regulating the duration of the locomotor step cycle, and hence the speed of the locomotion. This function is specific for V1 neurons, as we have not seen marked changes in the frequency or duration of the step cycle when either V0 or V3 neurons are deleted from the spinal cord5 (M.G., unpublished observations). Our conclusion that V1 neurons are necessary for ‘fast’ locomotor outputs in mice is supported by studies in Xenopus tadpoles showing that aIN neurons, the homologues of mouse V1 neurons, are the primary source of early cycle inhibition to the swimming locomotor CPG10. Although the role of aIN neurons in regulating the speed of Xenopus swimming movements was not examined, a strong correlation was seen between aIN-derived inhibitory inputs to CPG neurons and the frequency of swimming movements10. This raises the possibility that the Xenopus homologues of V1 neurons may facilitate fast swimming movements, in much the same way that their mammalian counterparts are required for fast ‘walking’ movements.

The exact contribution individual V1 interneuron subtypes make to regulating the duration of motor neuron bursting during fictive locomotion remains to be determined. Inhibition of Renshaw cells with cholinergic blockers causes a small increase in the step-cycle period26 (S.G. and O.K., unpublished observations), suggesting that a group of non-Renshaw V1 neurons or the V1 population as a whole regulates the step-cycle period during fictive locomotion. Although Renshaw cells and Ia inhibitory interneurons have described roles in coordinating flexor–extensor motor neurons during spinal reflexes27, our study demonstrates that the V1 population as a whole does not have a primary role in regulating locomotor CPG flexor–extensor activity. It therefore seems that an additional group of non-V1 interneurons have been incorporated into the walking CPG of terrestrial vertebrates to secure flexor–extensor alternation.

Our study also demonstrates that the acute silencing of a select population of neurons using genetic approaches can be used to elucidate their function with respect to a defined behaviour such as locomotion. Our results highlight the feasibility of using ligand-activated GIRK channels to selectively manipulate neuronal excitability in the vertebrate nervous system, and the conditional AlstR192 mice described here can be used to selectively silence neurons throughout the nervous system. This and similar genetic approaches now make it feasible to selectively probe the function of small populations of neurons, which should facilitate the mapping of neural circuits at higher resolutions than was previously possible.

Methods

Animals

The generation and genotyping of the _Pax6_lacZ, Sey, _En1_Cre, En1 tlZ, Wnt1 En1, _nestin_Cre, _R26_-_lacZ_flox/DTA, _R26_lacZ and _R26_GFP alleles in mice has been previously described8,9,12,23,28. Embryos and tissues were obtained from timed matings.

Generation of conditional AlstR mice

The Drosophila AlstR coding sequence, followed by an IRES-EGFP24, was inserted downstream of a _loxP_-flanked βgeo/polyA stop sequence in the conditional Z/EG construct29 to produce the Z/AlstR expression vector (see Fig. 4a). The linearized Z/AlstR construct was electroporated into the embryonic stem cell line W9.5. G418-resistant clones were screened for uniform and robust lacZ expression, and for single transgene integrants. Two clones gave germline transmission (AlstR172 and AlstR192). AlstR192 mice that showed lacZ expression throughout the nervous system were used for all further experiments.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

Immunostainings were performed as previously described5. Images were captured using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope and assembled using Adobe Photoshop. Cell numbers are indicated as mean ± s.d. per section per spinal cord side, and were determined on counts of at least three embryos (five sections each). In situ hybridization and staining for β-galactosidase activity were performed as previously described5,8.

Electrophysiology: electroneurogram recordings

Electrophysiological experiments were performed on E18.5–P2 mice in accordance with the ethical rules stipulated by NIH and the Swedish government. Animals were anaesthetized and decapitated, and spinal cords were dissected out in ice-cold Ringers' solution4. Recordings were made in Ringers' solution at 20 °C by placing bipolar suction electrodes on three of the second and fifth lumbar ventral roots (that is rL2, lL2, rL5, lL5). Electroneurogram signals were amplified, band-pass filtered (100 Hz–1 kHz), digitized and collected using Axoscope software (Axon Instruments). Rhythmic locomotor activity was induced by adding NMDA (5 µM) and 5-HT (5–30 µM) to the Ringers' solution. Effects of allatostatin (10 nM–5 µM) were examined by adding the peptide to the perfusion solution.

Electrophysiology: analysis of locomotor activity

Step-cycle period and burst duration were determined by analysing lL2 or rL2 activity4. Step-cycle period and burst duration averages were determined from all recorded bursts after the onset of stable locomotor-like activity. The effects of allatostatin were measured 10 min after application to allow for drug wash-in. All measurements are given ± s.d. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Circular statistics19 were used to determine the coupling strength between left and right ventral roots, as well as between flexor-related (L2) and extensor-related (L5) ventral roots on the same side of the spinal cord. L2 bursts were used as a reference. Vector points representing the phase values between 0 and 1 were plotted for each experiment, and show the mean phase as well as the concentration of phase values around the mean. Appropriate left–right or flexor–extensor alternation is represented by phase values around 0.5.

Electrophysiology: intracellular recordings

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from motor neurons were made using recording pipettes with a resistance of 4–5 MΩ. The microelectrode was driven into the spinal cord through a pial patch in the ventrolateral surface. Cells were patched in the motor neuron area and recorded using an AxoClamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments).

Electrophysiology: acute spinal cord slice recordings

For slice recordings, spinal cord slices 250–300-µm thick were cut using a Leica VY1000E vibrating microtome. After a 1-h recovery period, slices were transferred to a recording chamber, mounted on an Olympus BX51W1 microscope and perfused with oxygenated Ringers' solution at room temperature. GFP-positive cells were visualized using a DAGE-MTI IR-1000 CCD camera and patched visually using a Sutter MPC-325 micromanipulator. Recordings were made in current-clamp mode using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments).

Behavioural testing

Rotarod test were performed during the light phase of a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle as previously described30. Mice were placed on a Rotamex 4/8 (Columbus Instruments) idling at 5 r.p.m. Rotarod speed was set to increase gradually from 5 to 65 r.p.m. over the course of 3 min. Retention time on the rod was recorded for three trials per mouse per day for five consecutive days, using three mutant and three wild-type mice.

References

- Grillner, S. The motor infrastructure: from ion channels to neuronal networks. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 4, 573–586 (2003)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kiehn, O. & Kjaerulff, O. Distribution of central pattern generators for rhythmic motor outputs in the spinal cord of limbed vertebrates. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 860, 110–129 (1998)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Roberts, A., Soffe, S. R., Wolf, E. S., Yoshida, M. & Zhao, F. Y. Central circuits controlling locomotion in young frog tadpoles. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 860, 19–34 (1998)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Butt, S. J., Harris-Warrick, R. M. & Kiehn, O. Firing properties of identified interneuron populations in the mammalian hindlimb central pattern generator. J. Neurosci. 22, 9961–9971 (2002)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lanuza, G. M., Gosgnach, S., Pierani, A., Jessell, T. M. & Goulding, M. Genetic identification of spinal interneurons that coordinate left-right locomotor activity necessary for walking movements. Neuron 42, 375–386 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Angel, M. J., Jankowska, E. & McCrea, D. A. Candidate interneurones mediating group I disynaptic EPSPs in extensor motoneurones during fictive locomotion in the cat. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 563, 597–610 (2005)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jessell, T. M. Neuronal specification in the spinal cord: inductive signals and transcriptional codes. Nature Rev. Genet. 1, 20–29 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Saueressig, H., Burrill, J. & Goulding, M. Engrailed-1 and netrin-1 regulate axon pathfinding by association interneurons that project to motor neurons. Development 126, 4201–4212 (1999)

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Sapir, T. et al. Pax6 and _Engrailed_-1 regulate two distinct aspects of Renshaw cell development. J. Neurosci. 24, 1255–1264 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Li, W. C., Higashijima, S., Parry, D. M., Roberts, A. & Soffe, S. R. Primitive roles for inhibitory interneurons in developing frog spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 24, 5840–5848 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Higashijima, S., Masino, M. A., Mandel, G. & Fetcho, J. R. Engrailed-1 expression marks a primitive class of inhibitory spinal interneuron. J. Neurosci. 24, 5827–5839 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Brockschnieder, D. et al. Cell depletion due to diphtheria toxin fragment A after Cre-mediated recombination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 7636–7642 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ericson, J. et al. Pax6 controls progenitor cell identity and neuronal fate in response to graded Shh signaling. Cell 90, 169–180 (1997)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jiang, Z., Carlin, K. P. & Brownstone, R. M. An in vitro functionally mature mouse spinal cord preparation for the study of spinal motor networks. Brain Res. 816, 493–499 (1999)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kullander, K. et al. Role of EphA4 and EphrinB3 in local neuronal circuits that control walking. Science 299, 1889–1892 (2003)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Wenner, P., O'Donovan, M. J. & Matise, M. P. Topographical and physiological characterization of interneurons that express engrailed-1 in the embryonic chick spinal cord. J. Neurophysiol. 84, 2651–2657 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Alvarez, F. J. et al. Postnatal phenotype and localization of V1-derived interneurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 493, 177–192 (2005)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jankowska, E., Fu, T. C. & Lundberg, A. Reciprocal Ia inhibition during the late reflexes evoked from the flexor reflex afferents after DOPA. Brain Res. 85, 99–102 (1975)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kjaerulff, O. & Kiehn, O. Distribution of networks generating and coordinating locomotor activity in the neonatal rat spinal cord in vitro: a lesion study. J. Neurosci. 16, 5777–5794 (1996)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kiehn, O., Hounsgaard, J. & Sillar, K. T. in Neurons, Networks, and Motor Behaviour (eds Stein, P. S. G., Stuart, D., Selverston, A. & Grillner, S.) 47–59 (MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1997)

Google Scholar - Kjaerulff, O. & Kiehn, O. Crossed rhythmic synaptic input to motoneurons during selective activation of the contralateral spinal locomotor network. J. Neurosci. 17, 9433–9447 (1997)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Butt, S. J. & Kiehn, O. Functional identification of interneurons responsible for left-right coordination of hindlimbs in mammals. Neuron 38, 953–963 (2003)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Danielian, P. S. & McMahon, A. P. _Engrailed_-1 as a target of the Wnt-1 signalling pathway in vertebrate midbrain development. Nature 383, 332–334 (1996)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Lechner, H. A., Lein, E. S. & Callaway, E. M. A genetic method for selective and quickly reversible silencing of mammalian neurons. J. Neurosci. 22, 5287–5290 (2002)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Borodinsky, L. N. et al. Activity-dependent homeostatic specification of transmitter expression in embryonic neurons. Nature 429, 523–530 (2004)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Myers, C. P. et al. Cholinergic input is required during embryonic development to mediate proper assembly of spinal locomotor circuits. Neuron 46, 37–49 (2005)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Burke, R. E. in The Synaptic Organization of the Brain (ed. Shepherd, G. M.) 77–120 (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 1998)

Google Scholar - St-Onge, L., Sosa-Pineda, B., Chowdhury, K., Mansouri, A. & Gruss, P. Pax6 is required for differentiation of glucagon-producing α-cells in mouse pancreas. Nature 387, 406–409 (1997)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Novak, A., Guo, C., Yang, W., Nagy, A. & Lobe, C. G. Z/EG, a double reporter mouse line that expresses enhanced green fluorescent protein upon cre-mediated excision. Genesis 28, 147–155 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Brandon, E. P. et al. Choline transporter 1 maintains cholinergic function in choline acetyltransferase haploinsufficiency. J. Neurosci. 24, 5459–5466 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Rivier for the allatostatin peptide, P. Gruss and A. Mansouri for Pax6 mutant mice, P. Soriano for Rosa26 lacZ mice, A. McMahon for Wnt1 En1 mice, S. Narayan for generating ZnG reporter mice, and M. Gross, A. Joyner, S. Pfaff and P. Slesinger for materials. We thank G. Lemke, S. Pfaff, P. Gray and K. Quinlan for their comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (M.G., O.K.) and the Human Frontiers Science Program (O.K. and M.G.). G.M.L. was supported by an HFSP postdoctoral fellowship. Author Contributions are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Author information

Author notes

- Simon J. B. Butt

Present address: Department of Developmental Genetics, The Skirball Institute, New York University, New York, New York, 10016, USA - Simon Gosgnach and Guillermo M. Lanuza: *These authors contributed equally to this work

Authors and Affiliations

- Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory,

Simon Gosgnach, Guillermo M. Lanuza, Harald Saueressig, Ying Zhang, Tomoko Velasquez & Martyn Goulding - System Neurobiology Laboratory, The Salk Institute for Biological Studies, 10010 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California, 92037, USA

Edward M. Callaway - Mammalian Locomotor Laboratory, Department of Neuroscience, The Karolinska Institute, Retzius vag 8, 17177, Stockholm, Sweden

Simon J. B. Butt & Ole Kiehn - Centre for Molecular Neurobiology, University of Hamburg, 20251, Hamburg, Germany

Dieter Riethmacher

Authors

- Simon Gosgnach

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Guillermo M. Lanuza

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Simon J. B. Butt

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Harald Saueressig

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ying Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tomoko Velasquez

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Dieter Riethmacher

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Edward M. Callaway

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ole Kiehn

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Martyn Goulding

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence toMartyn Goulding.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Reprints and permissions information is available at npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Notes

This file contains additional information for Figure 1 and Figure 4 from the main text. This file also contains legends for the Supplementary Figure Legends and Author Contributions. (DOC 24 kb)

Supplementary Figure 1

Analysis of ventral neuron development in _Pax6_-/- and En1 Cre;R26-lacZ flox /DTA (En1-DTA) embryos. (PDF 302 kb)

Supplementary Figure 2

Acute allatostatin receptor-dependent neuronal silencing in the spinal cord. (PDF 122 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gosgnach, S., Lanuza, G., Butt, S. et al. V1 spinal neurons regulate the speed of vertebrate locomotor outputs.Nature 440, 215–219 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04545

- Received: 15 November 2005

- Accepted: 22 December 2005

- Issue Date: 09 March 2006

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04545