Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibres (original) (raw)

Abstract

Polyploidy often confers emergent properties, such as the higher fibre productivity and quality of tetraploid cottons than diploid cottons bred for the same environments1. Here we show that an abrupt five- to sixfold ploidy increase approximately 60 million years (Myr) ago, and allopolyploidy reuniting divergent Gossypium genomes approximately 1–2 Myr ago2, conferred about 30–36-fold duplication of ancestral angiosperm (flowering plant) genes in elite cottons (Gossypium hirsutum and Gossypium barbadense), genetic complexity equalled only by Brassica3 among sequenced angiosperms. Nascent fibre evolution, before allopolyploidy, is elucidated by comparison of spinnable-fibred Gossypium herbaceum A and non-spinnable Gossypium longicalyx F genomes to one another and the outgroup D genome of non-spinnable Gossypium raimondii. The sequence of a G. hirsutum AtDt (in which ‘t’ indicates tetraploid) cultivar reveals many non-reciprocal DNA exchanges between subgenomes that may have contributed to phenotypic innovation and/or other emergent properties such as ecological adaptation by polyploids. Most DNA-level novelty in G. hirsutum recombines alleles from the D-genome progenitor native to its New World habitat and the Old World A-genome progenitor in which spinnable fibre evolved. Coordinated expression changes in proximal groups of functionally distinct genes, including a nuclear mitochondrial DNA block, may account for clusters of cotton-fibre quantitative trait loci affecting diverse traits. Opportunities abound for dissecting emergent properties of other polyploids, particularly angiosperms, by comparison to diploid progenitors and outgroups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

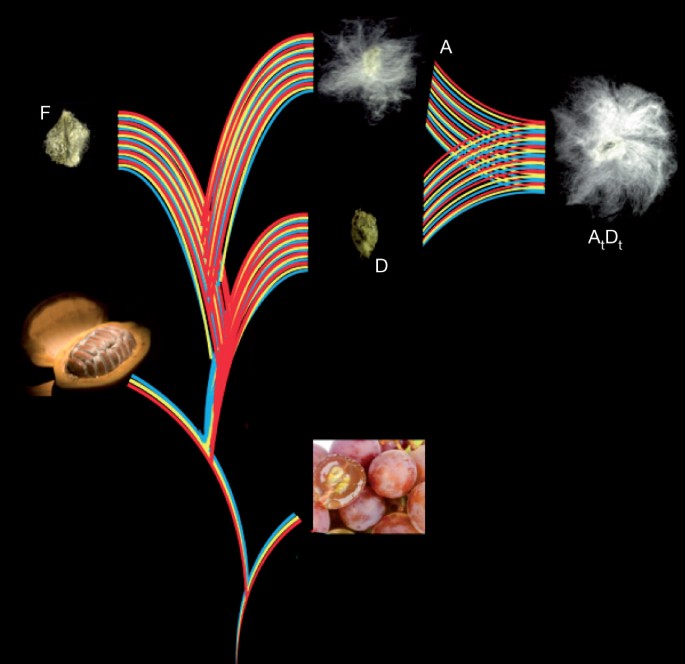

The Gossypium genus is ideal for investigating emergent consequences of polyploidy. A-genome diploids native to Africa and Mexican D-genome diploids diverged ∼5–10 Myr ago4. They were reunited ∼1–2 Myr ago by trans-oceanic dispersal of a maternal A-genome propagule resembling G. herbaceum to the New World2, hybridization with a native D-genome species resembling G. raimondii, and chromosome doubling (Fig. 1). The nascent AtDt allopolyploid spread throughout the American tropics and subtropics, diverging into at least five species; two of these species (G. hirsutum and G. barbadense) were independently domesticated to spawn one of the world’s largest industries (textiles) and become a major oilseed.

Figure 1: Evolution of spinnable cotton fibres.

Paleohexaploidy in a eudicot ancestor (red, yellow and blue lines) formed a genome resembling that of grape (bottom right). Shortly after divergence from cacao (bottom left), the Gossypium lineage experienced a five- to sixfold ploidy increase. Spinnable fibre evolved in the A genome after its divergence from the F genome, and was further elaborated after the merger of A and D genomes ∼1–2 Myr ago, forming the common ancestor of G. hirsutum (Upland) and G. barbadense (Egyptian, Sea Island and Pima) cottons.

New insight into Gossypium biology is offered by a genome sequence of G. raimondii Ulbr. (chromosome number, 13) with ∼8× longer scaffold N50 (18.8 versus 2.3 megabases (Mb)) compared with a draft5, and oriented to 98.3% (versus 52.4%5) of the genome (Supplementary Table 1.3a). Across 13 pseudomolecules totalling 737.8 Mb, ∼350 Mb (47%) of euchromatin span a gene-rich 2,059 centimorgan (cM), and ∼390 Mb (53%) of heterochromatin span a repeat-rich 186 cM (Supplementary Discussion, sections 1.5 and 2.1). Despite having the least-repetitive DNA of the eight Gossypium genome types, G. raimondii is 61% transposable-element-derived (Supplementary Table 2.1). Long-terminal-repeat retrotransposons (LTRs) account for 53% of G. raimondii, but only 3% of LTR base pairs derive from 2,345 full-length elements. The 37,505 genes and 77,267 protein-coding transcripts annotated (Supplementary Table 2.3 and http://www.phytozome.com) comprise 44.9 Mb (6%) of the genome, largely in distal chromosomal regions (Supplementary Discussion, section 2.1).

Shortly after its divergence from an ancestor shared with Theobroma cacao at least 60 Myr ago6, the cotton lineage experienced an abrupt five- to sixfold ploidy increase. Individual grape chromosome segments resembling ancestral eudicot genome structure, or corresponding cacao chromosome segments, generally have five (infrequently six) best-matching G. raimondii regions and secondary matches resulting from pan-eudicot hexaploidy7,8 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3.1). Paralogous genes tracing to this five- to sixfold ploidy increase show a single peak of synonymous nucleotide-substitution (_K_s) values, suggesting either one, or multiple closely spaced, event(s) (Supplementary Fig. 3.5). Pairwise cytological similarity among A-genome chromosomes9 suggests the most recent event was a duplication.

Figure 2: Syntenic relationships among grape, cacao and cotton.

a, Macro-synteny connecting blocks of >30 genes (grey lines). Highlighted regions (pink and red) trace to a common ancestor before the pan-eudicot hexaploidy7, with the Gossypium lineage five- to sixfold ploidy increase forming multiple derived regions. Inferred duplication depth in cotton varies (top). b, Micro-synteny of grape chromosome (Chr) 3, cacao chromosome 2 and five cotton chromosomes. Rectangles represent predicted genes, with connecting grey lines showing co-linear relationships. An example (1 grape, 1 cocoa, 5 cotton) is highlighted in red.

Paleopolyploidy may have accelerated cotton mutation rates: for 7,021 co-linearity-supported gene triplets, _K_s rates and non-synonymous nucleotide-substitution (_K_a) rates were, respectively, 19% and 15% larger for cotton–grape than cacao–grape comparisons (Supplementary Table 3.2). Adjusted for this acceleration (Supplementary Fig. 3.5), the cotton ploidy increase occurred about halfway between the pan-eudicot hexaploidy (<125 Myr ago10) and the present, near the low end of an estimated range of 57–70 Myr ago11.

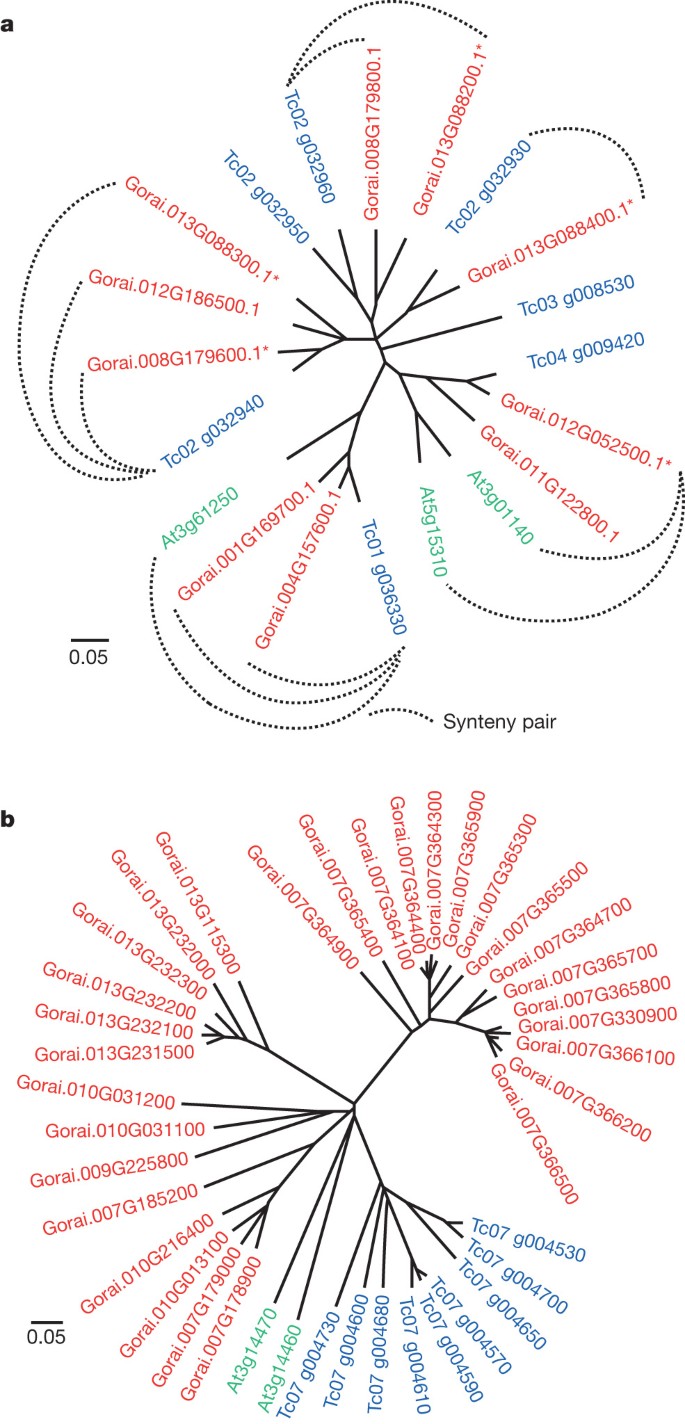

Paleopolyploidy increased the complexity of a Malvaceae-specific clade of Myb family transcription factors, perhaps contributing to the differentiation of epidermal cells into fibres rather than the mucilages of other Malvaceae. Among 204 R2R3, 8 R1R2R3 and 194 heterogeneous Myb transcription factors in G. raimondii (Supplementary Table 3.5), subgroup 9 has six members known only in Malvaceae (Fig. 3a), comprising a possible ‘fibre clade’ distinct from the _Arabidopsis thaliana GL1_-like subgroup 15 involved in trichome and root hair initiation and development12. Expressed predominantly in early fibre development, elite cultivated tetraploid cottons have higher expression of five (50%) of ten subgroup 9 genes compared with wild (undomesticated) tetraploids (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 5.3). Some subgroup 9 genes are also active in leaves, hypocotyls and cotyledons (Supplementary Fig. 3.8), consistent with specialization for different types of epidermal cell differentiation such as production of a ‘pulpy layer’ secreted from the teguments surrounding cacao seeds, and mucilages in other Malvaceae fruit (Abelmoschus (okra), Cola (kola)) and roots (Althaea (marshmallow)).

Figure 3: Paleo-evolution of cotton gene families.

a, Myb subgroup 9 (ref. 12) originated from a gene on the progenitor of cacao chromosome 2 that formed two adjacent copies after Malvales–Brassicales divergence and then triplicated in cotton, with subsequent loss of one chromosome 8 and two chromosome 12 paralogues. One extant paralogue traces to pan-eudicot hexaploidy, Tc04 g009420, and reduplicated in cotton (Gorai.012G052500.1 and Gorai.011G122800.1) and Arabidopsis8 (At3g01140 and At5g15310). The other, Tc01 g036330, has reduplicated in cotton (Gorai.004G157600.1 and Gorai.001G169700.1). Asterisk indicates increased gene expression in elite versus wild tetraploids (Supplementary Table 5.3). b, The most NBS-rich region of T. cacao, on chromosome 7, corresponds to regions of G. raimondii chromosome triplets 2/10/13 and 7/9/4. Cacao chromosome 7 NBSs form a single branch, indicating lineage-specific expansion. G. raimondii chromosome 7 and 13 NBSs form distinct branches, indicating cluster/tandem duplication (gene numbers also reflect physical proximity of genes to one another).

Cotton growers were early adopters of integrated pest management13 strategies to deploy intrinsic defences conferred by pest- and disease-resistance genes that evolved largely after the 5–6-fold ploidy increase. A total of 300 (0.8%) G. raimondii genes encode nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domains (Supplementary Table 3.6), largely of coiled-coil (CC)-NBS and CC-NBS-leucine rich repeat subgroups (165, 55%). Like cereals14, after paleopolyploidy G. raimondii evolved clusters of new NBS-encoding genes. The most NBS-rich (21%) region of T. cacao, on chromosome 7, corresponds to parts of G. raimondii chromosome triplets 2/10/13 and 7/9/4. In total, 27% and 25% of 294 mapped G. raimondii NBS genes are on these parts of chromosomes 7 and 9, often clustered in otherwise gene-poor surroundings (Supplementary Fig. 2.2). Most NBS clusters are species and chromosome specific (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 3.7), indicating rapid turnover and/or concerted evolution after cotton paleopolyploidy. In total, 230 (76.7%) NBS-encoding genes have experienced striking mutations (as detailed below) in the A genome since A–F divergence, reflecting an ongoing plant–pathogen ‘arms race’ (Supplementary Table 3.8).

Changes in gene expression during domestication have contributed to the deposition of >90% cellulose in cotton fibres, single-celled models for studying cell wall and cellulose biogenesis15. G. raimondii has at least 15 cellulose synthase (CESA) sequences required for cellulose synthesis16 (Supplementary Table 3.3), with four single-gene Arabidopsis clades having three (CESA3, required in expanding primary walls) or two (CESA4, CESA7 and CESA8, each required in the thickening of secondary walls) clade members in G. raimondii16. G. raimondii has at least 35 cellulose-synthase-like (CSL) genes required for synthesis of cell wall matrix polysaccharides that surround cellulose microfibrils16 (Supplementary Table 3.4), including one family (CSLJ) absent in Arabidopsis16. Elite tetraploids have higher expression than wild cottons in 6 (40%) of 15 CESA genes and 12 (34%) of 35 CSL genes (Supplementary Table 5.3).

A total of 364 G. raimondii microRNA precursors from 28 conserved and 181 novel families (Supplementary Table 3.12), are predicted regulators of 859 genes enriched for molecule binding factors, catalytic enzymes, transporters and transcription factors (Supplementary Fig. 3.11, 12). Four conserved and 35 novel mRNAs were specifically expressed in G. hirsutum fibres, respectively targeting 53 and 318 genes, most with homology to proteins involved in fibre development (Supplementary Table 3.14, 15). Among 183,690 short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) found, 33,348 (18.15%) were on chromosome 13 (Supplementary Fig. 3.12), a vast enrichment. Small RNA17,18,19 biogenesis proteins include 13 argonaute, 6 dicer-like (DCL) and 5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase orthologues (Supplementary Table 3.16). G. raimondii seems to be the first eudicot with two DCL3 genes and two genes encoding RNA polymerase IVa (Supplementary Table 3.16), perhaps relating to control of its abundant retrotransposons.

From unremarkable hairs found on all Gossypium seeds, ‘spinnable’ fibres (fibres with a ribbon-like structure that allows for spinning into yarn) evolved in the A genome after divergence from the B, E and F genomes ∼5–10 Myr ago4 (Fig. 1). To clarify the evolution of spinnable fibres, we sequenced the G. herbaceum A and G. longicalyx F genomes, which respectively differ from G. raimondii by 2,145,177 single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) and 477,309 indels, and 3,732,370 SNVs and 630,292 indels.

Specific genes are implicated in initial fibre evolution by both whole-gene and individual-nucleotide analyses. Across entire genes, 36 G. herbaceum_–_G. raimondii and 11 G. herbaceum_–_G. longicalyx orthologue pairs show evidence of diversifying selection (ω > 1, P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 4.1). A notable example, with _G. herbaceum_–_G. raimondii_ ω > 9, is Gorai.009G035800, a germin-like protein that is differentially expressed between normal and naked-seed cotton mutants during fibre expansion20 and between wild and elite G. barbadense at 10 days post-anthesis (DPA; Supplementary Table 5.3).

Among 114,202 SNVs in 29,015 G. herbaceum genes after G. herbaceum_–_G. longicalyx A–F divergence (using D as outgroup, so F is the same as D, and A differs from both), we identified striking mutations including 1,090 non-synonymous mutations in 959 genes comprising the most severe 1% of functional impacts inferred using a modified entropy function21; 3,525 frameshift mutations (3,021 genes), 1,077 (987) premature stops, 527 (513) splice-site mutations, 102 (102) initiation alterations and 95 (94) extended reading frames (Supplementary Table 4.2, 3). These striking mutations have an average genomic distribution (Supplementary Fig. 2.2) but are over-represented in genes coding for cell-wall-associated, kinase or nucleotide-binding proteins (Supplementary Table 4.5).

Striking mutations in the A-genome lineage are enriched (P = 2.6 × 10−18; Supplementary Discussion, section 4.4) within fibre-related quantitative trait locus (QTL) hotspots in AtDt tetraploid cottons22, suggesting that post-allopolyploidy elaboration of fibre development1 involved recursive changes in At and new changes in Dt genes. Striking A-genome mutations have orthologues in 1,051 Dt and 951 At fibre QTL hotspots. Likewise, sequencing of G. hirsutum cultivar Acala Maxxa revealed 495 striking mutations in 391 genes, with 83 (21.2%) in Dt fibre QTL hotspots and 73 (18.7%) in At hotspots (Supplementary Table 4.6).

QTL hotspots affecting multiple fibre traits22 may reflect coordinated changes in expression of functionally diverse cotton genes. A total of 671 (1.79%) genes with >100 reads per million reads were differentially expressed in fibres from wild versus domesticated G. hirsutum (mostly at 10 DPA) and/or G. barbadense (mostly at 20 DPA) (Supplementary Table 5.3). Among 48 genes upregulated in domesticated G. hirsutum at 10 DPA, 20 (42%) are among 1,582 (4.2%) genes within QTL hotspot Dt09.2 (ref. 22) affecting length, uniformity, and short-fibre content, with 13 (27%) out of 677 (1.8%) genes in homoeologous hotspot At09 affecting fibre elongation and fineness. Out of 45 genes downregulated in domesticated G. barbadense at 20 DPA, 16 (35.6%) map to Dt09.2, and 8 (17.7%) to At09. In 79% of cultivated G. barbadense, this At region (which was then thought to be on chromosome 5, and is now known to be on chromosome 9) has been unconsciously introgressed by plant breeders with G. hirsutum DNA, suggesting an important contribution to productivity of G. barbadense cultivars23.

A putative nuclear mitochondrial DNA (NUMT) sequence block24 has an intriguing relationship with fibre improvement. A G. raimondii chromosome 1 region includes many genes closely resembling mitochondrial homologues (_K_s ∼ 0.22; Supplementary Table 4.7a). NUMT genes experienced a coordinated change in expression associated with G. barbadense domestication. The 105 (0.2%) genes upregulated in 10 DPA fibre of wild (versus elite) tetraploid G. barbadense (Supplementary Table 5.3) include 30 (37%; P < 0.001) of the 81 NUMT genes, including 8 NADH dehydrogenase and 4 cytochrome-c-related genes. All are within the QTL hotspot Dt01 that affects fibre fineness, length, and uniformity22, suggesting a fibre-specific change in electron transfer in G. barbadense domestication.

Emergent features of polyploids may be related to processes that render them no longer the sum of their progenitors and permit them to explore transgressive phenotypic innovations. Despite the A-genome origin of spinnable fibres, after 1–2 Myr of co-habitation in tetraploid nuclei most At and Dt homoeologues are now expressed in fibres at similar levels (Supplementary Table 5.4). Such convergence is not ubiquitous: gene families involved in the synthesis of seed oil show strong A bias in wild G. hirsutum and its sister G. tomentosum, but strong D bias in an improved G. hirsutum (Supplementary Table 5.6).

Recruitment of Dt-genome genes into tetraploid fibre development1 may have involved non-reciprocal DNA exchanges from At genes. In the ∼40% of Acala Maxxa At and Dt genes that differ in sequence from their diploid progenitors (Fig. 4), most mutations are convergent, with At genes converted to the Dt state at more than twice the rate (25%) as the reciprocal (10.6%). Known to occur between cereal paralogues diverged by 70 Myr14, non-reciprocal DNA exchanges are more abundant between cotton At and Dt genes separated by only ∼5–10 Myr4. Such non-reciprocal exchanges explain prior observations including incongruent gene tree topology for 10% (3 pairs) of G. hirsutum At and Dt homeologues in sequenced bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) (Supplementary Discussion, section 5.3); 13.2% of tetraploid DNA markers that showed different subgenomic affinities compared with the chromosomes to which they mapped, 9 of 13 being Dt biased (At to Dt)25; and expressed-sequence-tag-based evidence of phylogenetic incongruity for as many as 7% of homeologous genes26.

Figure 4: Allelic changes between A- and D-genome diploid progenitors and the A t and D t subgenomes of G. hirsutum cultivar Acala Maxxa.

Several factors may have favoured Dt-biased allele conversion in tetraploid cotton. The nascent polyploid may have gained fitness from D-genome alleles native to its New World habitat. Before fortifying its reproductive barriers, the nascent polyploid may have occasionally outcrossed to nearby D-genome diploids, increasing the likelihood of illegitimate recombination. Outcrossing may also have contributed to the origin of Gossypium gossypioides, sister to G. raimondii and the only D-genome cotton containing many otherwise A-genome-specific repetitive DNAs27,28,29. Dt-biased allele conversion may have contributed to slightly greater protein-coding nucleotide diversity in the At compared with the Dt-genome (Supplementary Table 5.7).

Whereas the G. raimondii reference sequence and G. hirsutum short-read sequences reveal much about tetraploid cotton genome structure and polyploid evolution, high-contiguity sequencing of polyploids may elucidate still-cryptic features. Tetraploid cotton sequencing appears feasible: among six pairs of At and Dt BAC clones, the most similar pair shows 99.1% shared Dt-D and 97.6% At-D content (Supplementary Table 6.1), sufficient divergence to de-convolute shotgun sequence to the correct subgenome. Increased knowledge of molecular diversity is a foundation for integrating genomics with ecological and field-level knowledge of Gossypium species and their diverse adaptations to warm arid ecosystems on six continents.

Methods Summary

Sequencing

Reads were collected from Applied Biosystems 3730xl, Roche 454 XLR and Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx machines at the Joint Genome Institute (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/sequencing/protocols/prots_production.html) or HudsonAlpha Institute and Beckman Coulter Genomics (BAC end sequence), and USDA-ARS Mid-South Area Genomics Laboratory (G. longicalyx, G. arboreum and G. hirsutum).

Assembly

Assembly of 80,765,952 sequence reads used a modification of Arachne v.20071016, integrating linear (15× genome coverage) and paired (3.1× genome coverage) Roche 454 libraries corrected using 41.9 Gb Illumina sequence, with 1.54× paired-end Sanger sequences from two subclone, six fosmid and two BAC libraries. Cotton genetic and physical maps, and Vitis vinifera and T. cacao synteny were used to identify 51 joins across 64 scaffolds to form the 13 chromosomes (Supplementary Discussion, section 1). The remaining scaffolds were screened for contamination to produce a final assembly of 1,033 scaffolds (19,735 contigs) and 761.4 Mb. Sequences are in NCBI for G. raimondii (BioProject accession PRJNA171262), G. longicalyx (accession F1-1, SRA061660), G. herbaceum (accession A1-97, SRA061243) and G. hirsutum (cultivar Acala Maxxa, SRS375727) genomes; G. hirsutum (SRA061240) and G. barbadense (SRA061309) fibre transcriptomes; G. hirsutum (SRA061456) seed transcriptomes; and G. hirsutum microRNAs (SRA061415).

Annotation

PERTRAN software was used to construct transcript assemblies from ∼1.1 billion pairs of G. raimondii paired-end Illumina RNA-seq reads, 250 million G. raimondii single end reads, and 150 million G. hirsutum single end reads. PASA30 was used to build transcript assemblies from 454 and Sanger resources (Supplementary Table 2.3). Loci were determined by transcript assembly and/or EXONERATE alignments of A. thaliana, cacao, rice, soybean, grape and poplar peptides to repeat-soft-masked G. raimondii genome using RepeatMasker. Gene models were predicted by three homology-based predictors (Supplementary Discussion, section 2.2). Best-scoring gene predictions were improved by PASA, then filtered on the basis of peptide homology or expressed-sequence-tag evidence to remove Pfam transposable element domain models. ClustalW alignments of amino acid sequences (Fig. 3) were used to guide coding sequence alignments. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by bootstrap neighbour-joining with a Kimura 2-parameter model using ClustalW2, assessing internal nodes with 1,000 replicates.

Online Methods

Sequencing

Reads were collected with standard protocols (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/sequencing/protocols/prots_production.html) on Applied Biosystems 3730xl, Roche 454 XLR and Illumina Genome Analyzer (GA)IIx machines at the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute. Linear 454 data included standard XLR (47 runs, 16.868 Gb) and pre-release FLX+ data (5 runs, 3.262 Gb). Eight paired 454, 3–4-kilobase (kb) average insert size and one paired 12-kb average insert size were sequenced on standard XLR (23 runs, 5.931 Gb). One standard 400-base pair (bp) fragment library was sequenced at 2 × 150 (7 channels, 41.9 Gb) on an Illumina GAIIx. One 2.5-kb average insert size (405,024 reads, 286.1 Mb), one 6.5-kb average insert size library (374,125 reads, 263.0 Mb), six fosmid libraries (1,222,643 reads, 702.1 Mb) of 34–39-kb insert size, and two BAC libraries (107,520 reads, 77.5 Mb) of 98-kb and 115-kb (73,728 reads, 48.8 Mb) average insert size were sequenced on both ends for a total of 2,183,240 Sanger reads of 1.38 Gb of high-quality bases. FLX+ data were collected at the Roche Service Center. BAC end sequence (BES) was collected using standard protocols at the HudsonAlpha Institute.

Genome assembly and construction of pseudomolecule chromosomes

Organellar reads were removed by screening against mitochondria, chloroplast and ribosomal DNA. Any Roche 454 linear read <200 bp was discarded. Roche 454 paired reads in which either was shorter than 50 bp were discarded. An additional de-duplication step was applied to the 454 paired libraries that identifies and retains only one copy of each PCR duplicate. All remaining 454 reads were compared against a full Illumina GA2x run and any insertion/deletions in the 454 reads were corrected to match the Illumina alignments. The sequence reads were assembled using our modified version of Arachne v.20071016 (ref. 31) with parameters maxcliq1 = 100, correct1_passes = 0 and BINGE_AND_PURGE = True, bless = False maxcliq1 = 200 BINGE_AND_PURGE = True lap_ratio = 0.8 max_bad_look = 1000 (note Arachne error correction is on). This produced 1,263 scaffold sequences, with a scaffold L50 of 25.8 Mb, 58 scaffolds larger than 100 kb, and total genome size of 761.8 Mb. Scaffolds were screened against bacterial proteins, organelle sequences and non-redundant GenBank and removed if found to be a contaminant. Additional scaffolds were removed if they: (1) consisted of >95% 24-nucleotide sequences that occurred four other times in scaffolds larger than 50 kb; (2) contained only unanchored RNA sequences; or (3) were <1 kb in length.

The combination of BES/markers hybridized to fingerprint contigs32, 2,800 markers in a genetic map for the D genome in an AtDt plant33 and 262 markers from the tetraploid genetic map34, along with Vitis vinifera and T. cacao synteny was used to identify breaks in the initial assembly. Markers were aligned to the assembly using BLAT35 (parameters: -t = dna -q = dna −minScore = 200 –extendThroughN). BES, physical map contigs, V. vinifera and T. cacao genes were aligned to the genome using BLAST36. Scaffolds were broken if they contained linkage group/syntenic discontiguity coincident with an area of low BAC/fosmid coverage. A total of 13 breaks were executed, and 64 of the broken scaffolds were oriented, ordered and joined using 51 joins to form the final assembly containing 13 pseudomolecule chromosomes. Each chromosome join is padded with 10,000 missing nucleotides. The final assembly contains 1,033 scaffolds (19,735 contigs) that cover 761.4 Mb of the genome with a contig L50 of 135.6 kb and a scaffold L50 of 62.2 Mb.

The assembly size is near the centre of genome-size estimates of 880 Mb from flow cytometry37, 630 Mb from Feulgen cytophotometry38, and 650 Mb39 and 770 Mb40 from re-naturation kinetics.

Completeness of the euchromatic portion of the genome assembly was assessed using 65,506 G. raimondii complementary DNAs obtained from GenBank, which were aligned to the assembly using BLAT3 (parameters: -t = dna -q = rna –extendThroughN). The aim of the completeness analysis was to obtain a measure of completeness of the assembly, rather than a comprehensive examination of gene space. cDNAs were aligned to the assembly using BLAT35 (parameters: -t = dna -q = rna –extendThroughN) and alignments that comprised ≥90% base-pair identity and ≥85% EST coverage were retained. The screened alignments indicate that 57,170 out of 63,506 (90.3%) cDNAs aligned to the assembly. The cDNAs that failed to align were primarily composed of stretches of polynucleotide sequences that failed to generate non-random alignments to any plant or other organism in the NCBI as of the release date.

Annotation

A total of 85,746 transcript assemblies were constructed from about 1.1 billion pairs of D5 paired-end Illumina RNA-seq reads, 55,294 transcript assemblies from 250 million D5 single-end Illumina RNA-seq reads and 62,526 transcript assemblies from 150 million G. hirsutum cotton single-end Illumina RNA-seq reads. All these transcript assemblies were constructed using PERTRAN software (in preparation). In total, 120,929 transcript assemblies were built using PASA30 from 56,638 D5 Sanger ESTs, 2.5 million D5 Roche 454 RNA-seq reads and all of the RNA-seq transcript assemblies. An additional 133,073 transcript assemblies were constructed using PASA from 296,214 G. hirsutum cotton Sanger ESTs and about 2.9 million G. hirsutum cotton 454 reads. The larger number of transcript assemblies from fewer G. hirsutum sequences is due to the fragmented nature of the assemblies. Loci were determined by transcript assembly alignments and/or EXONERATE alignments of peptides from A. thaliana, cacao, rice, soybean, grape and poplar peptides to repeat-soft-masked D5 genome using RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org) with up to 2,000-bp extensions on both ends, unless extending into another locus on the same strand. Gene models were predicted by homology-based predictors, FGENESH+41, FGENESH_EST (similar to FGENESH+, EST as splice site and intron input instead of peptide/translated open-reading frames) and GenomeScan42. The best scored predictions for each locus are selected using multiple positive factors including EST and peptide support, and one negative factor: overlap with repeats. The selected gene predictions were improved by PASA. Improvement includes adding untranslated regions, splicing correction, and adding alternative transcripts. PASA-improved gene model peptides were subject to peptide-homology analysis to above-mentioned proteomes in order to obtain Cscore and peptide coverage. Cscore is a peptide BLASTP score ratio mutual best hit BLASTP score and peptide coverage is highest percentage of peptide aligned to the best of homologues. PASA-improved transcripts were selected on the basis of Cscore, peptide coverage, EST coverage and its coding sequence (CDS) overlapping with repeats. The transcripts were selected if their Cscore was larger than or equal to 0.5 and peptide coverage larger than or equal to 0.5, or if it had EST coverage, but its CDS overlapping with repeats was less than 20%. For gene models whose CDS overlaps with repeats for more than 20%, its Cscore needed to be at least 0.9 and homology coverage at least 70% to be selected. The selected gene models were subject to Pfam analysis and gene models whose peptide was more than 30% in Pfam transposable element domains were removed. The final gene set had 37,505 protein-coding genes and 77,267 protein-coding transcripts.

Accession codes

Primary accessions

Sequence Read Archive

Data deposits

Sequences have been deposited in NCBI for G. raimondii (BioProject accession PRJNA171262), G. longicalyx (accession F1-1, SRA061660), G. herbaceum (accession A1-97, SRA061243) and G. hirsutum (cultivar Acala Maxxa, SRS375727) genomes; G. hirsutum (SRA061240) and G. barbadense (SRA061309) fibre transcriptomes; G. hirsutum (SRA061456) seed transcriptomes; and G. hirsutum microRNAs (SRA061415).

References

- Jiang, C., Wright, R. J., El-Zik, K. M. & Paterson, A. H. Polyploid formation created unique avenues for response to selection in Gossypium (cotton). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 4419–4424 (1998)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Wendel, J. F. New world tetraploid cottons contain old-world cytoplasm. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 86, 4132–4136 (1989)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Wang, X. et al. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa . Nature Genet. 43, 1035–1139 (2011)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Senchina, D. S. et al. Rate variation among nuclear genes and the age of polyploidy in Gossypium . Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 633–643 (2003)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Wang, K. et al. The draft genome of a diploid cotton Gossypium raimondii . Nature Genet. 44, 1098–1103 (2012)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Carvalho, M. R., Herrera, F. A., Jaramillo, C. A., Wing, S. L. & Callejas, R. Paleocene Malvaceae from northern South America and their biogeographical implications. Am. J. Bot. 98, 1337–1355 (2011)

Article Google Scholar - Jaillon, O. et al. The French–Italian Public Consortium for Grapevine Genome Characterization. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in the major angiosperm phyla. Nature 449, 463–467 (2007)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Bowers, J. E., Chapman, B. A., Rong, J. & Paterson, A. H. Unravelling angiosperm genome evolution by phylogenetic analysis of chromosomal duplication events. Nature 422, 433–438 (2003)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Muravenko, O. V. et al. Comparison of chromosome BrdU–Hoechst–Giemsa banding patterns of the A1 and (AD)2 genomes of cotton. Genome 41, 616–625 (1998)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jiao, Y. et al. A genome triplication associated with early diversification of the core eudicots. Genome Biol. 13, R3 (2012)

Article Google Scholar - Fawcett, J. A., Maere, S. & Van de Peer, Y. Plants with double genomes might have had a better chance to survive the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 5737–5742 (2009)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Stracke, R., Werber, M. & Weisshaar, B. The R2R3-MYB gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana . Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 4, 447–456 (2001)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Adkisson, P. L., Niles, G. A., Walker, J. K., Bird, L. S. & Scott, H. B. Controlling Cotton’s insect pests: a new system. Science 216, 19–22 (1982)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Wang, X., Tang, H. & Paterson, A. H. Seventy million years of concerted evolution of a homoeologous chromosome pair, in parallel in major Poaceae lineages. Plant Cell 23, 27–37 (2011)

Article Google Scholar - Haigler, C. H., Betancur, L., Stiff, M. R. & Tuttle, J. R. Cotton fiber: a powerful single-cell model for cell wall and cellulose research. Front. Plant Sci. 3, 1–7 (2012)

Article Google Scholar - Doblin, M. S., Pettolino, F. & Bacic, A. Plant cell walls: the skeleton of the plant world. Funct. Plant Biol. 37, 357–381 (2010)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Baulcombe, D. RNA silencing in plants. Nature 431, 356–363 (2004)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Matzke, M. A. & Birchler, J. A. RNAi-mediated pathways in the nucleus. Nature Rev. Genet. 6, 24–35 (2005)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Brodersen, P. & Voinnet, O. The diversity of RNA silencing pathways in plants. Trends Genet. 22, 268–280 (2006)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kim, H. J. & Triplett, B. A. Cotton fiber germin-like protein. I. Molecular cloning and gene expression. Planta 218, 516–524 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Reva, B., Antipin, Y. & Sander, C. Predicting the functional impact of protein mutations: application to cancer genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e118 (2011)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Rong, J. et al. Meta-analysis of polyploid cotton QTL shows unequal contributions of subgenomes to a complex network of genes and gene clusters implicated in lint fiber development. Genetics 176, 2577–2588 (2007)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Wang, G. L., Dong, J. M. & Paterson, A. H. The distribution of Gossypium hirsutum chromatin in G. barbadense germ plasm: molecular analysis of introgressive plant-breeding. Theor. Appl. Genet. 91, 1153–1161 (1995)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Richly, E. & Leister, D. NUMTs in sequenced eukaryotic genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 1081–1084 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Reinisch, A. J. et al. A detailed RFLP map of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum × Gossypium barbadense): chromosome organization and evolution in a disomic polyploid genome. Genetics 138, 829–847 (1994)

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Flagel, L. E., Wendel, J. F. & Udall, J. A. Duplicate gene evolution, homoeologous recombination, and transcriptome characterization in allopolyploid cotton. BMC Genomics 13, 302 (2012)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Wendel, J. F., Schnabel, A. & Seelanan, T. An unusual ribosomal DNA sequence from Gossypium gossypioides reveals ancient, cryptic, intergenomic introgression. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 4, 298–313 (1995)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zhao, X. P. et al. Dispersed repetitive DNA has spread to new genomes since polyploid formation in cotton. Genome Res. 8, 479–492 (1998)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Cronn, R., Small, R. L., Haselkorn, T. & Wendel, J. F. Cryptic repeated genomic recombination during speciation in Gossypium gossypioides . Evolution 57, 2475–2489 (2003)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5654–5666 (2003)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jaffe, D. B. et al. Whole-genome sequence assembly for mammalian genomes: Arachne 2. Genome Res. 13, 91–96 (2003)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lin, L. et al. A draft physical map of a D-genome cotton species (Gossypium raimondii). BMC Genomics 11, 389–417 (2010)

Article Google Scholar - Rong, J.-K. et al. A 3347-locus genetic recombination map of sequence-tagged sites reveals features of genome organization, transmission and evolution of cotton (Gossypium). Genetics 166, 389–417 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Rong, J. et al. Comparative genomics of Gossypium and Arabidopsis: unraveling the consequences of both ancient and recent polyploidy. Genome Res. 15, 1198–1210 (2005)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kent, W. J. BLAT–the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 4, 656–664 (2002)

Article Google Scholar - Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hendrix, B. & Stewart, J. M. Estimation of the nuclear DNA content of Gossypium species. Ann. Bot. 95, 789–797 (2005)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kadir, Z. B. A. DNA evolution in the genus Gossypium . Chromosoma 56, 85–94 (1976)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Geever, R., Katterman, F. & Endrizzi, J. DNA hybridization analyses of Gossypium allotetraploid and two closely related diploid species. Theor. Appl. Genet. 77, 553–559 (1989)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Walbot, V. & Dure, L. S. Developmental biochemistry of cotton seed embryogenesis and germination. VII. Characterization of cotton genome. J. Mol. Biol. 101, 503–536 (1976)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Salamov, A. A. & Solovyev, V. V. Ab initio gene finding in Drosophila genomic DNA. Genome Res. 10, 516–522 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Yeh, R.-F., Lim, L. P. & Burge, C. Computational inference of homologous gene structures in the human genome. Genome Res. 11, 803–816 (2001)

Article CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

The work, conducted by the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, is supported by the Office of Science of the US Department of Energy under Contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The authors appreciate financial support from the US National Science Foundation (DBI 98-72630 to A.H.P., J.F.W., A.R.G.; DBI 02-11700 to J.F.W., A.H.P., J.U., A.R.G.; DBI 02-08311, IIP-0917856; IIP-1127755 to A.H.P.; IOS 1025947 to C.H.H.), USDA (ARS-58-6402-7-241, 58-6402-1-644 and 58-6402-1-645 to D.G.P.; ARS 6402-21310-003-00 to B.E.S.; NRI 00-52100-9685 and 02-35301-12045 to A.H.P.), Bayer CropScience and The Consortium for Plant Biotechnology Research (A.H.P.), Cotton, Inc. (P.W.C., D.C.J., A.H.P., D.M.S., A.V.-D., J.F.W.), Georgia State Support Committee (P.W.C., A.H.P.), Texas State Support Committee (R.J.W.), Pakistan–US Science and Technology Cooperation Program (P.W.C., S.M., A.H.P., M.u.R.), US–Egypt Science and Technology Cooperation Program (A.H.P., E.A.Z.), Fulbright Scholar Program (S.M., E.A.Z.), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico PDJ150690/2012-6 (E.R.), Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa Pensa Rio E-26/110.324/2010 (M.F.S.V.), Texas AgriLife (D.M.S.), and Brigham Young University (BYU) Mentored Environment Grants (J.U.). RNA-seq reads were mapped by students on Marylou at the Fulton Supercomputer Center at BYU. We thank L. S. Dure III, G. O. Myers, J. McD Stewart, T. A. Wilkins and J. Zhu for co-endorsing the sequencing of G. raimondii by the US Department of Energy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Plant Genome Mapping Laboratory, University of Georgia, Athens, 30602, Georgia, USA

Andrew H. Paterson, Hui Guo, Tae-ho Lee, Jingping Li, Lifeng Lin, Barry S. Marler, Xu Tan, Haibao Tang, Zining Wang, Dong Zhang, John E. Bowers, Sayan Das, Alan R. Gingle, Cornelia Lemke, Shahid Mansoor, Lisa N. Rainville, Jun-kang Rong & Xiyin Wang - Department of Ecology, Evolution and Organismal Biology, Iowa State University, Ames, 50011, Iowa, USA

Jonathan F. Wendel, Mi-jeong Yoo, Lei Gong, Corrinne Grover, Kara Grupp, Guanjing Hu, Emmanuel Szadkowski & Chunming Xu - MIPS/IBIS Institute for Bioinformatics and System Biology, German Research Center for Environmental Health (GmbH), 85764 Neuherberg, Germany ,

Heidrun Gundlach & Klaus F. X. Mayer - Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, Walnut Creek, 94595, California, USA

Jerry Jenkins, Shengqiang Shu, Jane Grimwood, Daniel S. Rokhsar & Jeremy Schmutz - HudsonAlpha Institute of Biotechnology, Huntsville, 35806, Alabama, USA

Jerry Jenkins, Jane Grimwood & Jeremy Schmutz - Center for Genomics and Computational Biology, School of Life Sciences, and School of Sciences, Hebei United University, Tangshan, Hebei 063000, China ,

Dianchuan Jin, Wei Chen, Tao Liu, Jinpeng Wang, Lan Zhang & Xiyin Wang - CSIRO Plant Industry, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia ,

Danny Llewellyn, Frank Bedon, Curt L. Brubaker, Sally A. Walford & Elizabeth S. Dennis - Institute for Genomics, Biocomputing & Biotechnology, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, 39762, Mississippi, USA

Kurtis C. Showmaker, William S. Sanders & Daniel G. Peterson - Plant and Wildlife Science Department, Brigham Young University, Provo, 84602, Utah, USA

Joshua Udall, Robert Byers, Justin T. Page, David Harker & Aditi Rambani - Department of Field Crops, Plant Sciences Institute, ARO, Bet-Dagan 50250, Israel,

Adi Doron-Faigenboim & Ran Hovav - Jamie Whitten Delta States Research Center, USDA-ARS, Stoneville, 38776, Mississippi, USA

Mary V. Duke, Brian E. Scheffler & Jodi A. Scheffler - Department of Biological Sciences, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, 02881, Rhode Island, USA

Alison W. Roberts - Departamento de Genética, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, 21941-901, Brazil,

Elisson Romanel - J. Craig Venter Institute, Rockville, 20850, Maryland, USA

Haibao Tang - Key Laboratory of Molecular Epigenetics of MOE, Unit of Plant Epigenetics, Institute of Genetics & Cytology, Northeast Normal University, Renmin Street, 5268 Changchun, China ,

Chunming Xu - Plant Reproductive Biology Extension Center, University of California, Davis, 95616, California, USA

Hamid Ashrafi & Allen Van Deynze - Bayer CropScience, Technologiepark 38, 9052 Gent, Belgium ,

Curt L. Brubaker - Coastal Plain Experiment Station, University of Georgia, Tifton, 31793, Georgia, USA

Peng W. Chee - Departments of Crop Science and Plant Biology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, 27695, North Carolina, USA

Candace H. Haigler - Centro Nacional de Pesquisa em Algodão, EMBRAPA, Santo Antônio de Góias, GO 75375-000, Brazil ,

Lucia V. Hoffmann - Cotton Incorporated, Cary, 27513, North Carolina, USA

Donald C. Jones - National Institute for Biotechnology & Genetic Engineering, Faisalabad 38000, Pakistan ,

Shahid Mansoor & Mehboob ur Rahman - Department of Biology, West Virginia State University, Institute, 25112, West Virginia, USA

Umesh K. Reddy - Robert H. Smith Institute of Plant Sciences and Genetics in Agriculture, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Rehovot 76100, Israel ,

Yehoshua Saranga - Department of Soil and Crop Science, Texas A&M University, College Station, 77843, Texas, USA

David M. Stelly - Cotton Fiber Bioscience Research, USDA-ARS, New Orleans, 70124, Louisiana, USA

Barbara A. Triplett - Departamento de Microbiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro 21941-971, Brazil,

Maite F. S. Vaslin - Central Institute for Cotton Research, Nagpur, 440010 Maharashtra, India ,

Vijay N. Waghmare - Department of Plant Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, 79415, Texas, USA

Robert J. Wright - Nucleic Acids Department, Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology Research Institute, 21934 Alexandria, Egypt,

Essam A. Zaki - Key Laboratory of Crop Genetics and Germplasm Enhancement, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, 210095 Jiangsu, China ,

Tianzhen Zhang

Authors

- Andrew H. Paterson

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jonathan F. Wendel

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Heidrun Gundlach

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hui Guo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jerry Jenkins

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Dianchuan Jin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Danny Llewellyn

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kurtis C. Showmaker

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Shengqiang Shu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Joshua Udall

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mi-jeong Yoo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Robert Byers

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Wei Chen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Adi Doron-Faigenboim

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mary V. Duke

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lei Gong

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jane Grimwood

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Corrinne Grover

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kara Grupp

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Guanjing Hu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tae-ho Lee

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jingping Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lifeng Lin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tao Liu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Barry S. Marler

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Justin T. Page

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Alison W. Roberts

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Elisson Romanel

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - William S. Sanders

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Emmanuel Szadkowski

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xu Tan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Haibao Tang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Chunming Xu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jinpeng Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zining Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Dong Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lan Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hamid Ashrafi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Frank Bedon

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - John E. Bowers

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Curt L. Brubaker

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Peng W. Chee

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sayan Das

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Alan R. Gingle

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Candace H. Haigler

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - David Harker

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lucia V. Hoffmann

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ran Hovav

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Donald C. Jones

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Cornelia Lemke

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Shahid Mansoor

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mehboob ur Rahman

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lisa N. Rainville

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Aditi Rambani

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Umesh K. Reddy

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jun-kang Rong

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yehoshua Saranga

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Brian E. Scheffler

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jodi A. Scheffler

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - David M. Stelly

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Barbara A. Triplett

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Allen Van Deynze

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Maite F. S. Vaslin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Vijay N. Waghmare

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sally A. Walford

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Robert J. Wright

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Essam A. Zaki

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tianzhen Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Elizabeth S. Dennis

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Klaus F. X. Mayer

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Daniel G. Peterson

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Daniel S. Rokhsar

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xiyin Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jeremy Schmutz

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

A.H.P., D.S.R., J.S. and D.G.P. conceived the study. J.S., J.G., D.S.R., K.C.S., S.D., M.V.D., C.L., L.N.R., B.E.S. and J.A.S. performed sequencing and associated clone manipulations. A.H.P., J.F.W., D.L., E.S.D., J.U., E.R., Z.W., H.A., L.V.H., R.H., D.M.S., A.V.-D. and T.Z. contributed unpublished data. A.H.P., J.F.W., H.Guo, H.Gundlach, J.J., D.J., D.L., S.S., J.U., M.-j.Y., R.B., W.C., A.D.-F., L.G., C.G., K.G., G.H., T.-h.L., J.L., L.L., T.L., B.S.M., J.T.P., A.W.R., E.R., E.S., X.T., H.T., C.X., J.W., Z.W., D.Z., L.Z., F.B., C.H.H., D.H., L.V.H., R.H., S.M., M.F.S.V., S.A.W., T.Z., E.S.D., D.S.R., X.W. and J.S. analysed data. A.H.P., J.F.W., D.L., E.S.D., K.F.X.M., D.G.P. and J.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence toAndrew H. Paterson or Jeremy Schmutz.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Text, Supplementary Tables, Supplementary Figures and Supplementary References – see contents for details. This file was replaced on 7 February 2013 to replace Supplementary Figure S3.10. (PDF 15998 kb)

Supplementary Data

This zipped file contains Supplementary Tables S3.5, S4.6, S4.7a and S5.3 – see Supplementary Information pdf for details. (ZIP 237 kb)

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Figure 3.8 - Phylogenetic relationships and clade designation in R2R3-MYB proteins from G. raimondii and A.thaliana (see Supplementary Information page 33 for full legend). This file was added on 7 February 2013. (PDF 370 kb)

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Figure S3.9 - Phylogenetic analysis of the R2R3-MYBs belonging to the MIXTA clade (subgroup 9) from sequenced plant genomes, including Gossypium raimondii (see Supplementary Information page 33 for full legend). This file was added on 7 February 2013. (PDF 2190 kb)

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/), which permits distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This licence does not permit commercial exploitation, and derivative works must be licensed under the same or similar licence.

About this article

Cite this article

Paterson, A., Wendel, J., Gundlach, H. et al. Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibres.Nature 492, 423–427 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11798

- Received: 17 August 2012

- Accepted: 21 November 2012

- Published: 19 December 2012

- Issue Date: 20 December 2012

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11798