Sequencing of diverse mandarin, pummelo and orange genomes reveals complex history of admixture during citrus domestication (original) (raw)

Abstract

Cultivated citrus are selections from, or hybrids of, wild progenitor species whose identities and contributions to citrus domestication remain controversial. Here we sequence and compare citrus genomes—a high-quality reference haploid clementine genome and mandarin, pummelo, sweet-orange and sour-orange genomes—and show that cultivated types derive from two progenitor species. Although cultivated pummelos represent selections from one progenitor species, Citrus maxima, cultivated mandarins are introgressions of C. maxima into the ancestral mandarin species Citrus reticulata. The most widely cultivated citrus, sweet orange, is the offspring of previously admixed individuals, but sour orange is an F1 hybrid of pure C. maxima and C. reticulata parents, thus implying that wild mandarins were part of the early breeding germplasm. A Chinese wild 'mandarin' diverges substantially from C. reticulata, thus suggesting the possibility of other unrecognized wild citrus species. Understanding citrus phylogeny through genome analysis clarifies taxonomic relationships and facilitates sequence-directed genetic improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Citrus are widely consumed worldwide as juice or fresh fruit, providing important sources of vitamin C and other health-promoting compounds. Global production in 2012 exceeded 86 million metric tons, with an estimated value of $9 billion (http://www.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/citrus.pdf). The very narrow genetic diversity of cultivated citrus makes them highly vulnerable to disease outbreaks, including citrus greening disease (also known as Huanglongbing or HLB), which is rapidly spreading throughout the world's major citrus-producing regions1. Understanding the population genomics and domestication of citrus will enable strategies for improvements, including resistance to greening and other diseases.

The domestication and distribution of edible citrus types began several thousand years ago in Southeast Asia and spread globally, following ancient land and sea routes. The lineages that gave rise to most modern cultivated varieties, however, have been lost in undocumented antiquity, and their identities remain controversial2,3. Several features of Citrus biology and cultivation make deciphering these origins difficult. Cultivated varieties are typically propagated clonally by grafting and through asexual seed production (apomixis via nucellar polyembryony) to maintain desirable combinations of traits (Fig. 1). Thus, many important cultivar groups have characteristic basic genotypes that presumably arose through interspecific hybridization and/or successive introgressive hybridizations of wild ancestral species. These domestication events predated the global expansion of citrus cultivation by hundreds or perhaps thousands of years, with no record of the domestication process. Diversity within such groups arises through accumulated somatic mutations, generally without sexual recombination, either as limb sports on trees or variants among apomictic seedling progeny.

Figure 1: A selection of mandarin, pummelo and orange fruits, including cultivars sequenced in this study.

Pummelos (1,2 in outline on left) are large trees that produce very large fruit with white, pink or red flesh color (2) and yellow or pink rinds. Most cultivars have large leaves with petioles with prominent wings. Apomictic reproduction is absent, and most selections are self-incompatible. Mandarins (3–7) are smaller trees bearing smaller fruit with orange flesh (9,11) and rind color. Mandarins have both apomictic and zygotic reproduction, and some are self-compatible. Oranges (8,10) are generally intermediate in tree and fruit size; the flesh (10) and rind color is commonly orange, and apomictic reproduction is always present. (The sour orange shown (12) is immature.)

Two wild species are believed to have contributed to domesticated pummelos, mandarins and oranges (Supplementary Note 1). 'Pummelos' have generally been identified with the wild species C. maxima (Burm.) Merrill, which is indigenous to Southeast Asia, on the basis of morphology and genetic markers. Although 'mandarins' are similarly widely identified with the species C. reticulata Blanco4,5,6, wild populations of C. reticulata have not been definitively described. Various authors have taken different approaches to classifying mandarins, and several naming conventions have been developed7,8. Here we emphasize that the term 'mandarin' is a commercial or popular designation, referring to citrus with small, easily peeled, sweet fruit, but is not necessarily a taxonomic one. We use the qualifier 'traditional' to refer to mandarins without previously suspected admixture from other ancestral species, to distinguish them from mandarin types that are known or believed to be recent hybrids. For clarity, we use × in the systematic name of such known hybrids (as described in ref. 9). Recognizing that genome sequencing and diversity analysis have provided insights into the domestication history of several other fruit crops10,11, cereals12,13 and other crops (reviewed in ref. 14), we sequenced and analyzed the genomes of a diverse collection of cultivated pummelos, mandarins and oranges (Supplementary Table 1) to test the pummelo-mandarin species hypothesis and to uncover the origins of several important citrus cultivars.

Results

A high-quality reference genome for citrus

To provide a genomic platform for analyzing Citrus, we generated a high-quality reference genome from ∼7× Sanger dideoxy whole-genome shotgun coverage of a haploid derivative of Clementine mandarin (C. × clementina cv. Clemenules)15 (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Tables 2–4). The use of haploid material (derived from a single ovule after induced gynogenesis15,16) removes complications that arise when assembling outbred diploid genomes. The resulting 301.4-Mb reference sequence is nearly complete, with superior assembly contiguity (contig L50 = 119 kb) and scaffolding (scaffold L50 before pseudochromosome construction = 6.8 Mb) compared to those of a recently published sweet-orange draft sequence17 (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Table 5). The long scaffolds allowed us to construct pseudochromosomes by assigning 96% of the assembly to a location on the nine citrus chromosomes by using the latest citrus genetic map18; in comparison, only 79% was assigned in the sweet-orange draft17 (Supplementary Note 2). We also inferred the phase of the two diploid Clementine haplotypes from sequence data, identifying ten crossovers from the meiosis that produced the haploid Clementine (Supplementary Fig. 1), and annotated nominal centromeres as large regions of low recombination (Supplementary Figs. 2–11). We also independently sequenced and assembled a draft genome of the (diploid) sweet-orange variety 'Ridge Pineapple' by combining deep 454 sequencing with light Sanger sampling (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Tables 5–10), and we inferred chromosome phasing by using the recently reported rough-draft genome of a sweet orange–derived dihaploid17.

The citrus genome retains substantial segmental synteny (that is, local collinearity) with other eudicots, although it has experienced extensive large-scale rearrangement on the chromosome scale (Supplementary Note 4). We propose a specific model, based on analysis of synteny, for the origin of the citrus genome from the paleohexaploid eudicot ancestor19 through a series of chromosome fissions and fusions (Supplementary Figs. 12–14). Despite the compactness of the citrus genome, 45% is repetitive, with long-terminal-repeat retrotransposons and numerous uncharacterized elements, each making up nearly half of the repetitive content; the remainder comprises DNA transposons and long interspersed elements (Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Table 11). We identified ∼25,000 protein-coding gene loci in both Clementine and sweet orange by computational methods combined with extensive long-read 454 and Sanger expressed-sequence-tags (Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Tables 12 and 13).

Investigation of citrus ancestry

To investigate the origin of cultivated varieties, we sequenced the genomes of four mandarins (including Clementine), two pummelos and one sour orange, as well as the sweet-orange genome reported above (Table 1, Supplementary Tables 1 and 14–16 and Supplementary Notes 1 and 6). (Cultivars derived from Citrus medica (the third purported wild species), i.e., citrons, limes and lemons, were not part of this study.) We aligned whole-genome shotgun reads from each cultivar to the sweet-orange chloroplast genome37 and identified high-quality single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) (Supplementary Note 6). We excluded indels and larger structural variants from this analysis. We readily identified two distinct types of chloroplast genomes (cpDNA), with mandarins all having one type (which we define as M for mandarin or C. reticulata) and pummelos and oranges sharing another type (defined as P for pummelo or C. maxima, with limited variation within each cpDNA type (Supplementary Note 6 and Supplementary Fig. 15), in agreement with prior studies of mitochondrial markers20. Citrus nuclear genomes tell a more complex story (Supplementary Notes 7–9 and Supplementary Tables 17–19). By aligning whole-genome shotgun reads to the haploid Clementine reference and identifying high-quality SNVs (Supplementary Note 6), we found that although the sequenced pummelos are evidently genotypes from the sexual C. maxima species with minimal introgression of other species, all the mandarin-type citrus that we sequenced show substantial admixture with pummelo and therefore cannot simply be selections from an ancestral C. reticulata population (Figs. 2 and 3). The sweet and sour oranges are also hybrids of varying complexity, with pummelo-type chloroplast genomes in both cases.

Table 1 Sequenced cultivars and proportions derived from the ancestral species C. reticulata and C. maxima

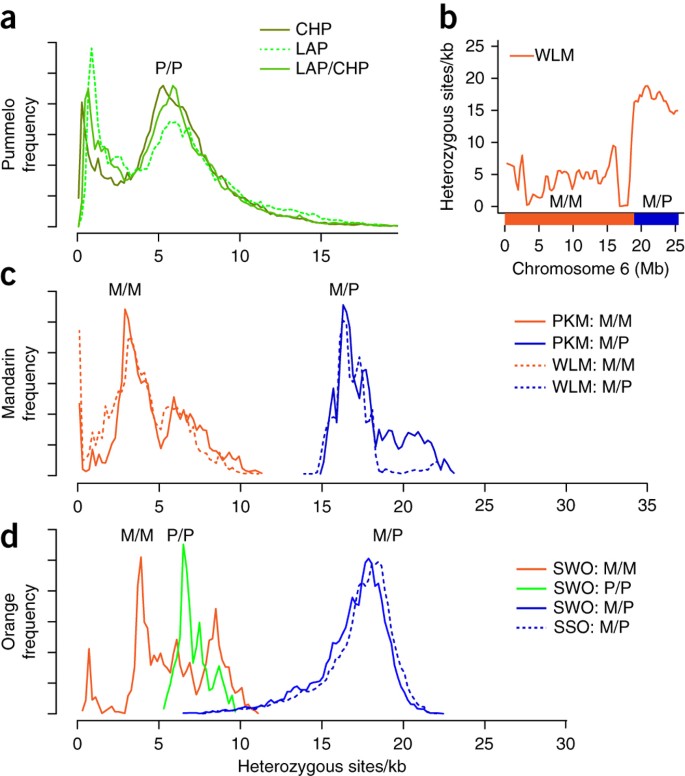

Figure 2: Nucleotide-diversity distribution in citrus.

(a) Nucleotide-heterozygosity distribution computed in overlapping 100-kb windows (with 5-kb step size) across the low-acid (LAP) and Chandler (CHP) pummelo genomes and between the nonshared haplotypes of this parent-child pair (LAP/CHP). The peak at ∼6 heterozygous sites/kb in all three pairwise comparisons represents the characteristic nucleotide diversity of the species C. maxima; the peak near ∼1 heterozygous site/kb reflects a bottleneck in the ancestral C. maxima population after divergence from C. reticulata (Supplementary Note 10). (b) Nucleotide heterozygosity for the traditional Willowleaf mandarin (WLM) plotted along chromosome 6, computed in overlapping windows of 200 kb (with 100-kb step size). This chromosome shows an example of the clear discontinuity in single-nucleotide-variant heterozygosity levels between ∼5/kb in the M/M segment (orange bar) and ∼17/kb in the M/P segment (blue bar). (c) Nucleotide heterozygosity distribution computed in overlapping 500-kb windows (with 5-kb step size) in Ponkan (PKM, solid line) and Willowleaf (WLM, dashed line) mandarins. Genomic segments are designated M/M, M/P or P/P on the basis of a set of 1,537,264 SNPs that differentiate C. reticulata (M) from C. maxima (P). Both mandarins contain admixed segments from C. maxima introgression (M/P) as well as M/M segments, and these are plotted and normalized separately for easy comparison. (d) Nucleotide heterozygosity distribution computed in overlapping windows of 500 kb (5-kb offsets) for sweet orange (SWO) and sour orange (SSO). The three different genotypes of the sweet-orange genome (M/M, P/P and M/P) and the sour-orange genotype M/P are normalized and plotted separately.

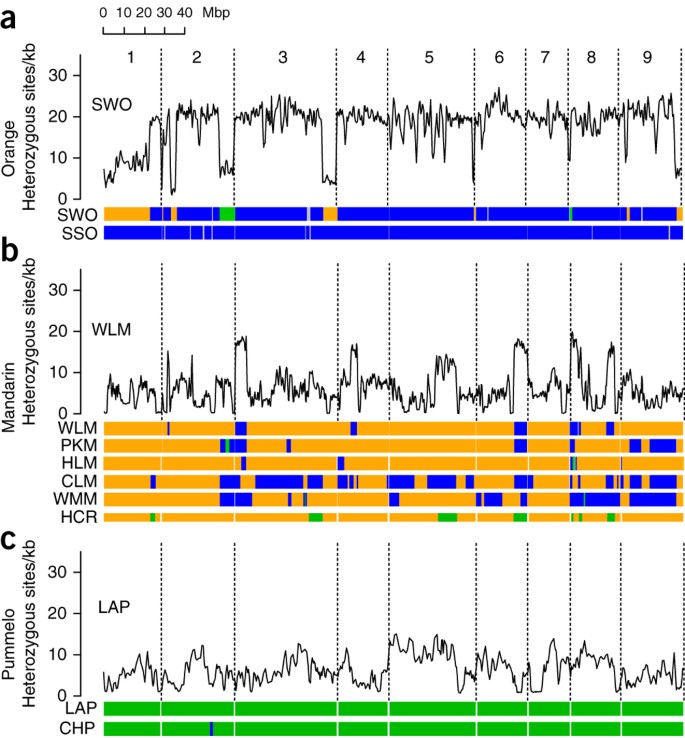

Figure 3: Admixture patterns and nucleotide diversity in cultivated citrus.

For each of the three groups of sequenced citrus, variation in nucleotide diversity (averaged over 500-kb windows with step size 250 kb) is shown across the genome for one representative cultivar above genotype maps (horizontal bars). Green, C. maxima/C. maxima; blue, C. maxima/C. reticulata; orange, C. reticulata/C. reticulata; gray, unknown. The nine chromosomes are numbered at top. (a) Sweet orange (SWO) nucleotide diversity with genotype maps for sweet orange and sour orange (SSO), indicating the C. maxima/C. maxima genotype (green segments present on chromosomes 2 and 8) in sweet orange. (b) Willowleaf mandarin (WLM) nucleotide diversity and genotype maps for three traditional mandarins (Ponkan mandarin (PKM), Willowleaf mandarin (WLM) and Huanglingmiao (HLM)) and three recent mandarin types (Clementine (CLM), W. Murcott mandarin (WMM) and haploid Clementine reference (HCR)). For the haploid Clementine reference sequence, orange and green segments indicate C. reticulata and C. maxima haplotypes, respectively. All five mandarin types show pummelo introgressions (blue or green segments). (c) Low-acid pummelo (LAP) nucleotide diversity and genotype maps for two pummelos (low-acid pummelo and Chandler pummelo (CHP)).

Ancestry of pummelos

The two diploid pummelos that we sequenced contain three distinct haplotypes, because low-acid (Siamese Sweet) pummelo is the known female parent of Chandler pummelo21, so that the two pummelos share one haplotype at each locus (Supplementary Note 9 and Supplementary Fig. 16). Within the two sequenced pummelos and between their nonshared alleles (derived from the other parent of Chandler, i.e., Siamese Pink pummelo) we observed modest levels of heterozygosity, with a genome-wide nucleotide heterozygosity of 5.7 heterozygous (het) sites/kb (Fig. 2a). The presence of a second low-heterozygosity peak (∼1 het site/kb) in the distribution can be explained by a strong ancient bottleneck in the C. maxima population ∼100,000–300,000 years ago (Supplementary Note 10). Our reanalysis of three Chinese pummelos previously reported17 (including the Wusuan pummelo, which we identify as coming from the same somatic lineage as Siamese Sweet pummelo) shows that both Thai and Chinese pummelos are derived from the same wild population (Supplementary Note 11). Only a single short 1.5-Mb segment on chromosome 2 of Chandler shows unusually high heterozygosity that could reflect interspecific introgression (Supplementary Fig. 17). These observations are consistent with pummelo domestication by selection from a wild sexual C. maxima population.

Ancestry of mandarins

The four mandarin genomes that we sequenced included a range of mandarin types: two traditional mandarins without prior suspected admixture (Ponkan, an old and widely grown Asian variety that was presumed to be typical of C. reticulata, and Willowleaf, a common Mediterranean variety) as well as two mandarins believed to be hybrids of traditional mandarins with other citrus (Clementine, the diploid parent of the haploid reference accession, and W. Murcott, believed to be synonymous with the cultivar also known as Nadorcott and Afourer and widely grown in California and the Mediterranean (Supplementary Note 1)). In contrast to those of pummelos, the mandarin accessions that we sequenced typically include segments of high nucleotide heterozygosity (∼17 het sites/kb, consistently with interspecific variation) that span tens of centimorgans or megabase pairs (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 18). These highly heterozygous blocks are interspersed with long segments of substantially lower levels of heterozygosity (∼5 het sites/kb) that are consistent with intraspecific variation and are clearly distinct from the higher-heterozygosity blocks (Fig. 2c). In the lower-heterozygosity segments, both alleles are often distinct from those observed in the pummelos and presumably derive from C. reticulata, which is widely cited as the true species from which cultivated mandarins arose7. In contrast, we found that the higher-heterozygosity blocks typically carry one allele that matches the pummelos and one nonpummelo allele, also presumably C. reticulata. The presumptive C. reticulata alleles are typically common to multiple mandarin accessions, thus further supporting their identification.

Our surprising conclusion is that traditional mandarin types, such as Ponkan and Willowleaf, are in fact interspecific introgressions of C. maxima (pummelo) into C. reticulata (wild mandarin). Furthermore, although these traditional mandarins were previously thought to be unrelated, we detected extensive haplotype sharing between them (Supplementary Note 10 and Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20). Because microsatellite-based population structure analyses of a wide range of citrus genotypes show mandarins as a defined cluster of genotypes22, such admixture is probably widespread among mandarin types. Indeed, reanalysis of a recently sequenced Chinese mandarin17 in the light of our discovery of interspecific introgression in multiple mandarin types, shows that the traditional Chinese Huanglingmiao mandarin (incorrectly treated previously16 as a pure C. reticulata) also exhibits unsuspected admixture between C. reticulata and C. maxima (Supplementary Note 11, Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 21).

Although none of our cultivated mandarin genotypes represent pure C. reticulata, we can nevertheless extract wild mandarin alleles from our data by comparing the (admixed) cultivated mandarins with each other and with the two pure pummelos. By such genome-wide comparisons, we identified 1,537,264 putative fixed single-nucleotide differences between C. reticulata and C. maxima (Supplementary Fig. 22, Supplementary Data Set 1 and Supplementary Note 7). These diagnostic variants can in turn be used to partition the mandarin, pummelo and orange genomes into segments according to their species ancestry (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 23). The characterization of C. reticulata genomic segments from modern mandarins is analogous to the extraction of African haplotypes from Mexican Americans23 and Native American haplotypes from extant ethnic human populations that are admixtures with American, African and European roots24.

We can estimate the parameters of a simple population-genetic model for the divergence of C. reticulata and C. maxima from an ancestral South Asian citrus founder population, using a coalescent framework and our collection of fixed interspecific differences and intraspecific variation (Supplementary Note 9 and Supplementary Figs. 24–26). This analysis is consistent with effective population sizes of several hundred thousand trees for C. maxima and somewhat fewer for C. reticulata, with a larger effective population size for pummelos, in keeping with their higher heterozygosity. The likely occurrence of apomixis in wild mandarin populations, a trait that seems to be absent in C. maxima, may contribute to reducing the effective C. reticulata population size relative to the census size. If we assume a per-site mutation rate (μ) of ∼1–2 × 10−9/y (comparable to that observed in poplar trees25), then we can estimate that C. reticulata and C. maxima diverged ∼1.6–3.2 Myr ago; this is consistent with the divergence between Citrus and the related genus Poncirus, which is estimated at 4–9.6 Myr ago (ref. 26). As noted, the excess of low-heterozygosity segments in pummelo is consistent with a substantial population bottleneck several hundred thousand years ago and before the separation of Thai and Chinese pummelo lineages (Supplementary Notes 9 and 11 and Supplementary Fig. 27).

Some specific citrus genotypes are generally recognized as hybrid varieties. For example, Clementine mandarin (also known as Algerian tangerine) is believed to be a chance seedling from a Mediterranean mandarin (e.g., Willowleaf) selected just over a century ago in Algeria27. Although various male parents have been proposed, serological and molecular studies demonstrated that the Clementine was likely to be a hybrid of mandarin and sweet orange6,18,28. We confirm this hypothesis at the sequence level by definitively identifying a Willowleaf and sweet-orange allele at each Clementine locus; by demarcating the recombination breakpoints in the meiosis that produced the haploid Clementine sequence; and by determining the Willowleaf and sweet-orange haplotypes that contributed to diploid Clementine (Supplementary Note 10 and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 28–31). Similarly, the W. Murcott mandarin is believed to be a chance zygotic seedling of Murcott tangor, itself a presumed F1 hybrid of sweet orange and an unknown mandarin. Our sequence analysis is consistent with the suspected grandparent-grandchild relationship between sweet orange and W. Murcott (Supplementary Note 10). Although the other parent and grandparent of W. Murcott are not known, a search for these ancestors will be enabled by the other observed alleles.

Ancestry of oranges

Sweet orange (Citrus × sinensis L. Osbeck) is the citrus type most widely cultivated for fruit and juice and is widely believed to be an interspecific hybrid, but its origin is unknown4,6. Different sweet-orange cultivars share the same genomic organization with little sequence variation, having arisen by mutation from the original sweet-orange domesticate (as described, for example, in ref. 29). Using our genome-wide catalog of fixed C. reticulata versus C. maxima alleles, we can represent the sweet-orange genome as segments of these two parental species or hybrid segments thereof (Supplementary Note 10 and Fig. 2d), with clear boundaries between different segment types (Fig. 3a). A recently proposed (P × M) × M backcross scheme for the derivation of sweet orange from mandarin and pummelo17, however, is easily ruled out by the presence of clear P/P (i.e., C. maxima/C. maxima) segments in sweet orange, which would require both parents to have some pummelo ancestry. (The P/P segment on chromosome 2 has been confirmed by directed resequencing of three genes in this region30.)

Unexpectedly, in our analysis we found that sweet orange shares alleles with Ponkan mandarin across nearly three-quarters of the genome, and many of the same segments are also shared with Willowleaf and Huanglingmiao (Supplementary Note 10 and Supplementary Fig. 32). This leads to the surprising conclusion that these three traditional mandarins, previously considered to be independent selections, in fact show substantial kinship with each other and with an ancestor of sweet orange, thus suggesting much more limited genetic diversity among the traditional mandarins than has previously been recognized (Supplementary Note 10). The nature of the other parent of sweet orange is more difficult to infer, but the distribution of heterozygous segments in sweet orange (Supplementary Fig. 33) and its pummelo-type chloroplast genome would be more readily accounted for if the female parent were itself a pummelo with substantial introgression of wild mandarin (Supplementary Note 9).

Finally, Seville or sour orange (also known as Citrus × aurantium), which has historically been an important rootstock for citrus and, more familiarly, is used in marmalade and other products, is another traditional cultivar type that is widely regarded as a pummelo-mandarin hybrid. Our genomic analysis shows that sour orange is indeed the direct result of a simple interspecific F1 cross between a pummelo (C. maxima) seed parent and a wild-mandarin (C. reticulata) pollen parent (Supplementary Note 10 and Supplementary Fig. 34). Surprisingly in light of our discovery of widespread pummelo admixture among traditional mandarins, no such admixture is found in the C. reticulata parent of sour orange, but the specific parental genotypes remain unknown. Sour orange may have arisen as a natural hybrid of two wild Citrus species and persisted by virtue of its reproduction through apomixis and subsequent deliberate human cultivation and distribution. We found no detectable recent relationship between sweet and sour orange.

Chinese Mangshan is a distinct species, C. mangshanensis

Among cultivars traditionally classified as mandarins, however, we found another surprise. Our analysis of the genome of a presumed wild mandarin from Mangshan, China17 (CMS) shows (i) a chloroplast genome distinct from that of both C. reticulata and C. maxima (Fig. 4a); (ii) limited heterozygosity (Fig. 4b), again uniformly distributed across the genome, with no segments of pummelo or mandarin ancestry, thus indicating no admixture; and (iii) ∼2% homozygous differences from both C. reticulata and C. maxima uniformly across the genome, a rate comparable to the divergence between C. maxima and C. reticulata (Fig. 4b). At the level of nucleotide diversity, CMS is as diverged from C. maxima and C. reticulata as C. maxima and C. reticulata are from each other (Fig. 4b), and it is clearly separated from pummelos, oranges and mandarins by principal coordinate analysis (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Note 11). By all these measures, we find that Mangshan mandarin is unrelated to the other cultivated mandarins discussed above (including Huanglingmiao mandarin). We therefore propose that, despite its morphology, Mangshan mandarin represents a distinct species from C. reticulata, supporting the nomenclature C. mangshanensis31.

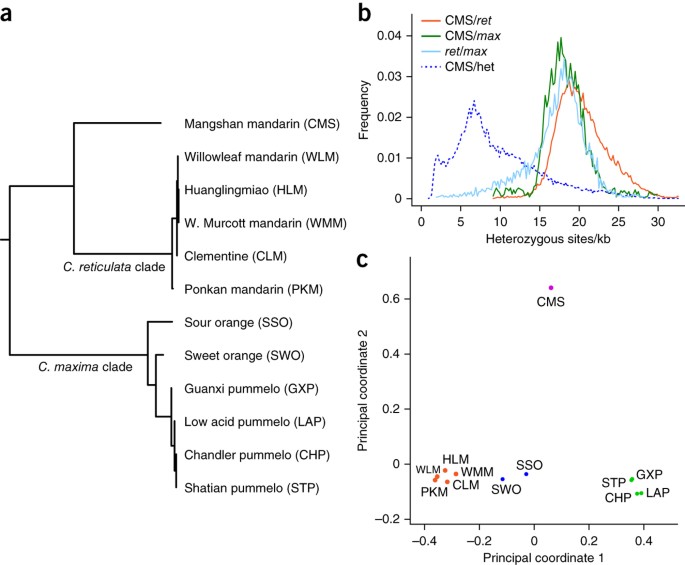

Figure 4: Mangshan mandarin is a species distinct from C. maxima and C. reticulata.

(a) Midpoint-rooted neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of citrus chloroplast genomes. (b) Frequency distributions of the pairwise sequence divergences (across 100-kb windows) between Mangshan mandarin (CMS) and C. maxima (green), CMS and C. reticulata (orange), C. reticulata and C. maxima (light blue) as well as the distinctly lower CMS intrinsic nucleotide diversity (dashed blue). Ret, C. reticulata; max, C. maxima; het, heterozygous. (c) The first two coordinates of principal coordinate analysis of the citrus nuclear genomes, based on pairwise distances and metric multidimensional scaling. The C. maxima_–_C. reticulata axis (principal coordinate 1, 47.5% variance) separates pummelos (green) from mandarins (orange), with oranges (blue) lying in between; principal coordinate 2 (19.6% of variance) separates CMS (purple) from the others.

Discussion

Our genomic analyses clarify some of the murky early history of citrus domestication. The nuclear and chloroplast genomes of cultivated pummelos are consistent with the identification of pummelos as a single Citrus species, C. maxima. In contrast, the nuclear genomes of sequenced mandarin-type cultivars all contain substantial admixture of C. maxima, despite the similarity of mandarin chloroplast sequences. Our results thus show that the various conventional Citrus taxonomies that associate mandarin citrus types with the ancestral Citrus species C. reticulata are too simplistic. It is particularly surprising that even the traditional mandarin types with no prior suspicion of relatedness or admixture, such as Ponkan, Willowleaf and Huanglingmiao mandarin, show substantial haplotype sharing and all include introgressed pummelo segments. A supposed wild mandarin from Mangshan, China turns out to represent a distinct taxon only distantly related to C. reticulata, on the basis of analysis of its nuclear and chloroplast genomes. (In a previous analysis of sweet-orange ancestry17, Mangshan mandarin Clementine and Huanglingmiao were used to represent C. reticulata. Our discovery of substantial pummelo admixture in Clementine and Huanglingmiao, and the distinctness of Mangshan mandarin from C. reticulata, further invalidate the conclusions in ref. 17.)

Remarkably, even in the absence of a pure type specimen for C. reticulata, we can characterize the genome of this wild mandarin progenitor species from genome-wide comparative analysis of admixed descendants23. Our collection of 1,537,264 SNPs (Supplementary Data Set 1) that differentiate C. reticulata from C. maxima can be used to guide the search for pure C. reticulata mandarin types (or to recognize other cryptic species) among the hundreds of known cultivars and other germplasm accessions. Small-fruited mandarins that are less desirable for fresh consumption on the basis of appearance, flavor, texture and aroma may be considered likely candidates. With the discovery that C. mangshanensis is a distinct group, the possibility of additional yet-undescribed wild Citrus species must also be considered.

The prevalence of interspecific admixture in cultivated citrus suggests that either early in domestication or in a natural hybrid zone before domestication, C. reticulata and C. maxima interbreeding occurred. Given the typical size of the hybrid blocks, only a few generations of introgression occurred before the selection of attractive cultivars, which were then propagated asexually by apomictic or vegetative means, perhaps in southern China32. Our analysis of sweet orange and sour orange shows that these ancient and widely cultivated genotypes are pummelo-mandarin admixtures that are unrelated to each other, despite some degree of phenotypic similarity33. The discovery that sour orange is a simple F1 hybrid of C. maxima and C. reticulata implies that pure C. reticulata individuals were part of the breeding germplasm at the origin of sour orange. Remarkably, we found that extant Ponkan, Willowleaf and Huanglingmiao mandarins are related to each other and to the male parent of sweet orange. Although the female parent of sweet orange remains unknown, it cannot have been a pure pummelo (though it had pummelo cytoplasm, on the basis of cpDNA and mitochondrial DNA20). Its identity is constrained by the high proportion of hybrid P/M segments in sweet orange, which could be naturally explained if the female parent of sweet orange were (P × M) × P.

Like many other agricultural enterprises, the global citrus industry relies substantially on large-scale monoculture, and this makes it particularly challenging to meet consumer demand for greater product diversity while trying to incorporate tolerance and/or resistance to biotic and potentially catastrophic abiotic stresses34. Advances in citrus genomics35,36 should soon allow the identification of the somatic mutations that, with their ancient genetic backgrounds, underlie the diversity of citrus color, flavor and aroma in modern cultivars. Our analysis of the relationships between cultivated citrus and the ancestral species from which they were derived emphasizes the limited ancestral germplasm that contributed to the commercially important cultivar types, such as sweet orange, and highlights the opportunities for the creation of new combinations of the ancestral citrus types with new fruit quality traits or even the re-creation of sweet orange with improved disease resistance via sexual hybridization, beyond the current approaches based on somatic mutations and genetic engineering.

Methods

Haploid C. × clementina 'Clemenules' sequencing and assembly.

A total of 4.6 million Sanger reads (including 469,000 fosmid-end and 73,000 BAC-end reads), were obtained from an induced haploid plant C. × clementina 'Clemenules', assembled with Arachne and integrated with a genetic map producing chromosome-scale pseudomolecules (nearly 97% of ESTs aligned to the genome) (Supplementary Note 2).

C. × sinensis genome sequencing and assembly.

A total of 16.5 Gb sequence (36 million 454 reads and 750,000 Sanger PE reads) was generated from C. × sinensis 'Ridge Pineapple' and assembled with Newbler (Supplementary Note 3).

Annotation of repeats and genes in citrus genome assemblies.

Repeat analysis was performed separately in the Clementine and sweet-orange genomes. The method used RepeatModeler to find new repeats in the genome sequence, which were masked with RepeatMasker. Following this, PASA was used to align and assemble ESTs (1.6 million for Clementine; 6.5 million for sweet orange) and integrate Fgenesh+, exonerate and GenomeScan gene predictions to generate gene models (Supplementary Note 4).

Evolutionary comparisons with other plant genomes.

Evolutionary comparisons to plant genomes used ortholog assignment to generate chromosome-to-chromosome relationships within and between genomes and predict ancestral genome structures (Supplementary Note 5).

Analysis of resequencing data sets.

Illumina shotgun sequence reads from eight accessions (17 × −110 × depth; Table 1) were mapped to the haploid Clementine reference with bwa, and single-nucleotide variants were identified with SAMtools and in-house scripts (Supplementary Note 6). Heterozygosity in diploid accessions was estimated in windows of 100–500 kb by division of the number of confidently inferred heterozygous single nucleotide variant ('het') sites by the number of eligible sites in the window at which confident variant calls could be made, on the basis of depth and alignment quality (Supplementary Note 6).

Identification of two ancestral species (C. maxima versus C. reticulata alleles) and admixture analysis.

Diagnostic alleles for the two ancestral Citrus species, C. maxima and C. reticulata, were derived from a comparative analysis of two pummelos and two traditional mandarin types and were used to study the admixture patterns in the sequenced cultivars (Supplementary Notes 7 and 8).

Population genetic analysis and simulations.

Population genetic analysis of the two citrus species and demographic inference were based on coalescent simulations conducted with MaCS (Supplementary Note 10).

Analysis of relatedness in citrus.

Parentage and relatedness analysis for Clementine and other citrus genomes made use of homozygous SNPs in each diploid genome relative to the haploid Clementine reference as well as to the inferred second haplotype of Clementine (Supplementary Notes 9 and 11). In the same way, the haploid sweet-orange assembly was used for identifying shared haplotypes with sweet orange (Supplementary Note 9). A modified identical-by-state (IBS) method was used for haplotype-sharing analysis among mandarins and other citrus pairs (Supplementary Note 9).

Accession codes.

The reference haploid Clementine assembly and annotation has been deposited in the NCBI genome database under accession code AMZM00000000. Sanger whole-genome sequencing for Clementine has been deposited in the NCBI trace archive under SPECIES_CODE='CITRUS CLEMENTINA'. This Whole-genome shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under accession code JJOQ00000000. Whole-genome sequencing data for sweet orange have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject PRJNA225968 (454-sequencing data) and in the NCBI trace archive under SPECIES_CODE='CITRUS SINENSIS' AND CENTER_NAME ='JGI'. Citrus resequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the following accession codes: SRX372786 (sour orange), SRX372703 (sweet orange), SRX372702 (low-acid pummelo), SRX372688 (Chandler pummelo), SRX372685 (Willowleaf mandarin), SRX372687 (W. Murcott mandarin), SRX372665 (Ponkan mandarin) and SRX371962 (Clementine mandarin).

Accession codes

Primary accessions

BioProject

NCBI Reference Sequence

Sequence Read Archive

References

- Bové, J. Huanglongbing: a destructive, newly-emerging, century-old disease of citrus. J. Plant Pathol. 88, 7–37 (2006).

Google Scholar - The Citrus Industry 1st edn, Vol. 1 (eds. Reuther, W., Webber, H.J. & Batchelor, L.D.). (University of California, Division of Agricultural Sciences, Berkeley, California, USA, 1967).

- Spiegel-Roy, P. & Goldschmidt, E.E. Biology of citrus (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York, 1996).

- Scora, R.W. On the history and origin of citrus. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 102, 369–375 (1975).

Article Google Scholar - Barrett, H.C. & Rhodes, A.M. A numerical taxonomic study of affinity relationships in cultivated citrus and its close relatives. Syst. Bot. 1, 105–136 (1976).

Article Google Scholar - Nicolosi, E. et al. Citrus phylogeny and genetic origin of important species as investigated by molecular markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 100, 1155–1166 (2000).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Swingle, W.T. & Reece, H.C. in The Citrus Industry 2nd edn, Vol. 1 (eds. Reuther, W., Webber, H.J. & Batchelor, L.D.) 190–430 (University of California Press, Berkeley, California, USA, 1967).

- Tanaka, T. Fundamental discussion of Citrus classification. Studia Citrologica 14, 1–6 (1977).

Google Scholar - Moore, G.A. Oranges and lemons: clues to the taxonomy of Citrus from molecular markers. Trends Genet. 17, 536–540 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Cornille, A. et al. New insight into the history of domesticated apple: secondary contribution of the European wild apple to the genome of cultivated varieties. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002703 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Myles, S. et al. Genetic structure and domestication history of the grape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 3530–3535 (2011).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Huang, X. et al. A map of rice genome variation reveals the origin of cultivated rice. Nature 490, 497–501 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hufford, M.B. et al. Comparative population genomics of maize domestication and improvement. Nat. Genet. 44, 808–811 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Morrell, P.L., Buckler, E.S. & Ross-Ibarra, J. Crop genomics: advances and applications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 85–96 (2011).

Article Google Scholar - Germana, M.A. et al. Cytological and molecular characterization of three gametoclones of Citrus clementina. BMC Plant Biol. 13, 129 (2013).

Article Google Scholar - Aleza, P. et al. Recovery and characterization of a Citrus clementina Hort. ex Tan. 'Clemenules' haploid plant selected to establish the reference whole Citrus genome sequence. BMC Plant Biol. 9, 110 (2009).

Article Google Scholar - Xu, Q. et al. The draft genome of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis). Nat. Genet. 45, 59–66 (2013).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ollitrault, P. et al. A reference genetic map of C. clementina hort. ex Tan.: citrus evolution inferences from comparative mapping. BMC Genomics 13, 593 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Salse, J. In silico archeogenomics unveils modern plant genome organisation, regulation and evolution. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15, 122–130 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Froelicher, Y. et al. New universal mitochondrial PCR markers reveal new information on maternal citrus phylogeny. Tree Genet. Genomes 7, 49–61 (2011).

Article Google Scholar - Cameron, J.W.S. R K Chandler: an early-ripening hybrid pummelo derived from a low-acid parent. Hilgardia 30, 359–364 (1961).

Article Google Scholar - Barkley, N.A., Roose, M.L., Krueger, R.R. & Federici, C.T. Assessing genetic diversity and population structure in a citrus germplasm collection utilizing simple sequence repeat markers (SSRs). Theor. Appl. Genet. 112, 1519–1531 (2006).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Johnson, N.A. et al. Ancestral components of admixed genomes in a Mexican cohort. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002410 (2011).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Bustamante, C.D., Burchard, E.G. & De la Vega, F.M. Genomics for the world. Nature 475, 163–165 (2011).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Tuskan, G.A. et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science 313, 1596–1604 (2006).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Pfeil, B.E. & Crisp, M.D. The age and biogeography of Citrus and the orange subfamily (Rutaceae: Aurantioideae) in Australasia and New Caledonia. Am. J. Bot. 95, 1621–1631 (2008).

Article Google Scholar - Trabut, J.L. L'hybridation des Citrus: une nouvelle tangérine 'la Clémentine'. Revue Horticole 10, 232–234 (1902).

Google Scholar - Samaan, L.G. Studies on the origin of Clementine tangerine (Citrus reticulata Blanco). Euphytica 31, 167–173 (1982).

Article Google Scholar - Novelli, V.M., Cristofani, M., Souza, A.A. & Machado, M.A. Development and characterization of polymorphic microsatellite markers for the sweet orange (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck). Genet. Mol. Biol. 29, 90–96 (2006).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Garcia-Lor, A. et al. A nuclear phylogenetic analysis: SNPs, indels and SSRs deliver new insights into the relationships in the 'true citrus fruit trees' group (Citrinae, Rutaceae) and the origin of cultivated species. Ann. Bot. 111, 1–19 (2013).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Liu, G.F., He, S.W. & Li, W.B. Two new species of citrus in China. Acta Botanica Yunnanica 12, 287–289 (1990).

Google Scholar - Gmitter, F.G. & Hu, X. The possible role of Yunnan, China, in the origin of contemporary citrus species (Rutaceae). Econ. Bot. 44, 267–277 (1990).

Article Google Scholar - Morton, J.F. Fruits of Warm Climates (Florida Flair Books, Miami, 1987).

- Gottwald, T.R. Current epidemiological understanding of citrus Huanglongbing. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 48, 119–139 (2010).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Talon, M. & Gmitter, F.G. Jr. Citrus genomics. Int. J. Plant Genomics 2008, 528361 (2008).

Article Google Scholar - Gmitter, F.G. et al. Citrus genomics. Tree Genet. Genomes 8, 611–626 (2012).

Article Google Scholar - Bausher, M.G., Singh, N.D., Lee, S.B., Jansen, R.K. & Daniell, H. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck var 'Ridge Pineapple': organization and phylogenetic relationships to other angiosperms. BMC Plant Biol. 6, 21 (2006).

Article Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the following support: National Science and Technology Institute of Genomics for Citrus Breeding, Brazil, grants FAPESP 08/57909-2 and CNPq 573848/08-4, and Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa) (M.A.T. and M.A.M.) and Embrapa-Monsanto Agreement (J.F.-A.); Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) grant CITRUSSEQ PCS-08-GENO (O.J., X.P., M. Ruiz, P.O., F.L., D.B. and K.J.) and program ANR Blanc-PAGE, ref. ANR-2011-BSV6-00801 (J. Salse and F.M.); US National Institutes of Health grant HG00783 (M.B., P.B. and A.L.); Generalitat Valenciana, Spain grant PrometeoII/2013/008 and Ministry of Economy and Innovation–Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER), Spain, grant AGL2011-26490 (P.A. and L.N.); Conselleria de Agricultura, Pesca, Alimentación y Água from the Generalitat Valenciana (J.P.-P. and D. Ramón); Ministerio de Economia e Innovación grants PSE-060000-2009-8 and IPT-010000-2010-43 and Citruseq-Citrusgenn consortium companies (Anecoop S. Coop., Eurosemillas S.A., Fundación Ruralcaja Valencia, GCM Variedades Vegetales A.I.E., Investigación Citrícola Castellón S.A. and Source Citrus Genesis–Special New Fruit Licensing, Ltd.) (J.T., F.R.T., L.H.E., J.V.M.-S., V.I., A.H.-O. and M.T.); Florida Citrus Production Research Advisory Council (FCPRAC), Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services grant no. 013646, Florida Department of Citrus (FDOC) and Citrus Research and Development Foundation grant no. 71, on behalf of the Florida citrus growers (F.G., C.C. and W.G.F.); Ministero delle Politiche Agricole Alimentari e Forestali, Project Citrustart and Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca (MIUR), Programma Operativo Nazionale 'Ricerca e Competitività' 2007–2013, Project IT-Citrus Genomics PON_01623 (M. Morgante, S.S., F.C., C.D.F., S. Pinozio and A.Z.). Pineapple Ridge sweet-orange sequencing was performed by 454 Life Sciences, a Roche company. The work conducted by the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute is supported by the Office of Science of the US Department of Energy under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Author information

Author notes

- Chunxian Chen & Tim Harkins

Present address: Present addresses: Life Technologies, Grand Island, New York, USA (T.H.) and US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Southeastern Fruit and Tree Nut Research Laboratory, Byron, Georgia, USA (C.C.)., - G Albert Wu and Simon Prochnik: These authors contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

- US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, Walnut Creek, California, USA

G Albert Wu, Simon Prochnik, Uffe Hellsten, Jarrod Chapman & Daniel Rokhsar - HudsonAlpha Biotechnology Institute, Huntsville, Alabama, USA

Jerry Jenkins, Jane Grimwood & Jeremy Schmutz - Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA), Université Blaise Pascal (UBP) UMR 1095 Génétique, Diversité, Ecophysiologie des Céréales (GDEC), Clermont Ferrand, France

Jerome Salse & Florent Murat - Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement (CIRAD), UMR Amélioration Génétique et Adaptation des Plantes Méditerranéennes et Tropicales (AGAP), Montpellier, France

Xavier Perrier, Manuel Ruiz & Patrick Ollitrault - Istituto di Genomica Applicata, Udine, Italy

Simone Scalabrin, Federica Cattonaro, Cristian Del Fabbro, Sara Pinosio, Andrea Zuccolo & Michele Morgante - Centro de Genomica, Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Agrarias (IVIA), Valencia, Spain

Javier Terol, Francisco R Tadeo, Leandro H Estornell, Juan V Muñoz-Sanz, Victoria Ibanez, Amparo Herrero-Ortega & Manuel Talon - Centro de Citricultura Sylvio Moreira, Instituto Agronômico (IAC), Cordeirópolis, Brazil

Marco Aurélio Takita, Juliana Freitas-Astúa & Marcos Antonio Machado - Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique (CEA), Institut de Génomique (IG), Genoscope, Evry, France

Karine Labadie, Julie Poulain, Arnaud Couloux, Kamel Jabbari, Dominique Brunel, Francis Quetier, Patrick Wincker & Olivier Jaillon - Institute of Life Sciences, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Pisa, Italy

Andrea Zuccolo - Centro de Protección Vegetal y Biotecnología–Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Agrarias, Moncada, Spain

Pablo Aleza & Luis Navarro - Lifesequencing, Valencia, Spain

Julián Pérez-Pérez & Daniel Ramón - Secugen, Madrid, Spain

Julián Pérez-Pérez - INRA, US 1279 Etude du Polymorphisme des Génomes Végétaux (EPGV), Evry, France

Dominique Brunel - INRA Génétique et Écophysiologie de la Qualité des Agrumes (GEQA), San Giuliano, France

François Luro - Citrus Research and Education Center (CREC), Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS), University of Florida, Lake Alfred, Florida, USA

Chunxian Chen & Frederick Gmitter - Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA

William G Farmerie - 454 Life Sciences, Roche, Branford, Connecticut, USA

Brian Desany, Chinnappa Kodira, Mohammed Mohiuddin, Tim Harkins & Karin Fredrikson - Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

Paul Burns, Alexandre Lomsadze & Mark Borodovsky - School of Computational Science and Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

Paul Burns, Alexandre Lomsadze & Mark Borodovsky - Department of Biological and Medical Physics, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dolgoprudny, Russia

Mark Borodovsky - Consiglio per la Ricerca e la Sperimentazione in Agricoltura (CRA-ACM), Acireale, Italy

Giuseppe Reforgiato - Embrapa Cassava and Fruits, Cruz das Almas, Brazil

Juliana Freitas-Astúa - Département de Biologie, Université d'Evry, Evry, France

Francis Quetier, Patrick Wincker & Olivier Jaillon - Department of Botany and Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside, Riverside, California, USA

Mikeal Roose - Centre National de Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Evry, France

Patrick Wincker & Olivier Jaillon - Department of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, University of Udine, Udine, Italy

Michele Morgante - Division of Genetics, Genomics and Development, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, California, USA

Daniel Rokhsar

Authors

- G Albert Wu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Simon Prochnik

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jerry Jenkins

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jerome Salse

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Uffe Hellsten

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Florent Murat

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xavier Perrier

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Manuel Ruiz

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Simone Scalabrin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Javier Terol

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Marco Aurélio Takita

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Karine Labadie

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Julie Poulain

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Arnaud Couloux

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kamel Jabbari

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Federica Cattonaro

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Cristian Del Fabbro

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sara Pinosio

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Andrea Zuccolo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jarrod Chapman

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jane Grimwood

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Francisco R Tadeo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Leandro H Estornell

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Juan V Muñoz-Sanz

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Victoria Ibanez

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Amparo Herrero-Ortega

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Pablo Aleza

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Julián Pérez-Pérez

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Daniel Ramón

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Dominique Brunel

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - François Luro

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Chunxian Chen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - William G Farmerie

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Brian Desany

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Chinnappa Kodira

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mohammed Mohiuddin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tim Harkins

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Karin Fredrikson

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Paul Burns

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Alexandre Lomsadze

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mark Borodovsky

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Giuseppe Reforgiato

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Juliana Freitas-Astúa

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Francis Quetier

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Luis Navarro

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mikeal Roose

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Patrick Wincker

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jeremy Schmutz

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Michele Morgante

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Marcos Antonio Machado

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Manuel Talon

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Olivier Jaillon

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Patrick Ollitrault

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Frederick Gmitter

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Daniel Rokhsar

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

G.A.W., development and application of methods to analyze citrus genetic diversity, population history and ancestry; S. Prochnik, genome annotation and initial analysis of genetic diversity; J.J., J.G. and J.C., sequence assembly and map integration of haploid Clementine reference; J. Salse and F.M., analysis of synteny and genome evolution.; U.H., analysis of population history and ancestry; K.L., J.P.-P., A.C., J.P., D.B. and K.J., dideoxy shotgun sequencing and analysis of haploid Clementine reference; S.S., S. Pinosio, A.Z., C.D.F., X.P. and M. Ruiz, analysis of sequencing and resequencing data, and repetitive sequence annotation and analysis; F.C., Sanger and Illumina sequencing; A.L., P.B. and M.B., sweet-orange gene model predictions; C.C. and W.G.F., 454 sequencing of sweet orange and Illumina sequencing of Siamese Sweet pummelo; C.C., contributions to sweet-orange transcriptome, annotation and strategic rationale for comparative analyses; P.A., J.P.-P. and L.N., haploid Clementine DNA; J.P.-P. and D. Ramón, haploid Clementine transcriptome; J.T., F.R.T., L.H.E., J.V.M.-S., V.I., A.H.-O. and M.T., generation of BAC clones of the haploid Clementine and contribution of genome sequences of sweet orange, Ponkan, diploid Clementine and Willowleaf mandarins; B.D., C.K., M. Mohiuddin, T.H. and K.F., sweet-orange 454 transcriptome and genome sequencing and assembly; M.A.M. and M.A.T., Ponkan shotgun sequence; M. Roose, W. Murcott shotgun sequence; M. Morgante, Chandler pummelo and Seville sour-orange shotgun sequence; G.R., J.F.-A., F.Q., L.N., F.L. and M. Roose, project coordination; D. Rokhsar, F.G., G.A.W. and S. Prochnik, writing of the paper with substantial input from M.T., P.O., M. Mohiuddin, O.J. and M. Roose; F.G., D. Rokhsar, O.J., P.O., M.A.M., M. Morgante, M.T., J. Schmutz and P.W., project coordination and scientific leadership.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence toFrederick Gmitter or Daniel Rokhsar.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/), which permits distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This license does not permit commercial exploitation, and derivative works must be licensed under the same or similar license.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, G., Prochnik, S., Jenkins, J. et al. Sequencing of diverse mandarin, pummelo and orange genomes reveals complex history of admixture during citrus domestication.Nat Biotechnol 32, 656–662 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2906

- Received: 09 October 2013

- Accepted: 14 April 2014

- Published: 08 June 2014

- Issue Date: July 2014

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2906