X-linked inheritance of Fanconi anemia complementation group B (original) (raw)

We previously purified a Fanconi anemia core complex containing five known Fanconi anemia proteins and four unknown components, called Fanconi anemia–associated polypeptides (FAAPs). We showed that FAAP43 (also called FANCL) is a ubiquitin ligase and was defective in an individual affected with Fanconi anemia belonging to a new complementation group (FA-L)3,7 (Fig. 1a). Here we report that FAAP95 (also called FAAP90) is mutant in individuals with Fanconi anemia belonging to complementation group B (FA-B).

Figure 1: FANCB is a member of the core complex required for monoubiquitination of FANCD2.

(a) Silver-stained SDS-PAGE gel showing the immunopurified Fanconi anemia core complex7. The polypeptide previously called FAAP90 is now called FAAP95 because its relative molecular mass is 95 kDa. (b) Immunoblotting of polypeptides obtained from immunoprecipitation (IP) with antibodies to FANCA or FAAP95. Immunoblotting of the nuclear extract (NE) was included to show the correct size of the Fanconi anemia proteins (except FAAP95). (c) Immunoblotting of Fanconi anemia core complex proteins immunoisolated with a Flag antibody from 293 cells stably expressing Flag-FANCL. Immunoprecipitation by FAAP95 antibody was analyzed as a control. Asterisks indicate two nonspecific polypeptides that crossreact with antibody to FAAP95. (d) Immunoblotting of lysates of HeLa cells depleted of FAAP95 by siRNA. HeLa cells treated with a scrambled siRNA oligonucleotide were included as a control.

Analysis by mass spectrometry identified FAAP95 as FLJ34064, a hypothetical protein of unknown function. A polyclonal antibody raised against FLJ34064 specifically recognized the 95-kDa polypeptide of the Fanconi anemia core complex immunopurified by an antibody to FANCA, indicating that FLJ34064 is FAAP95 (Fig. 1b). Immunoblotting also detected the presence of FAAP95 in Fanconi anemia core complex proteins immunoisolated by a Flag antibody from 293 cells stably expressing Flag-tagged FANCL7 (Fig. 1c). Reciprocal immunoprecipitation with the antibody to FAAP95 showed coprecipitation of several components of the Fanconi anemia core complex, such as FANCL, FANCA and FANCG (Fig. 1b,c and data not shown). These data suggest that FAAP95 is a stable component of the Fanconi anemia core complex. We also found that FAAP95 coimmunoprecipitated much more FANCL than FANCA or FANCG, suggesting that the interaction between FAAP95 and FANCL might be direct.

Notably, depletion of FAAP95 reduced the amount of monoubiquitinated FANCD2 (Fig. 1d), similar to depletion of other components of the Fanconi anemia core complex7,8, indicating that FAAP95 is a functional component of this complex. In addition, cells depleted of FAAP95 had less FANCL, suggesting that FAAP95 is required for the stability of FANCL.

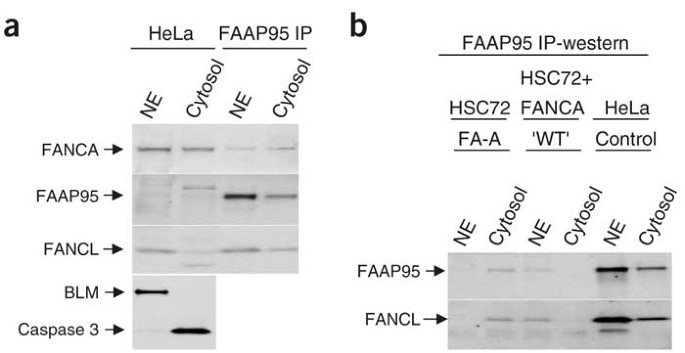

FAAP95 has sequence homologs in mouse and chicken, but not in Drosophila melanogaster or Caenorhabditis elegans. The C terminus of this protein contains a putative bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS; Supplementary Fig. 1 online), and we found that most of the protein was present in the nuclear extract of HeLa cells (Fig. 2a). Notably, FAAP95 was retained mostly in the cytosolic extract of a FANCA-deficient cell line but became localized to the nuclear extract on complementation by wild-type FANCA (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2 online). In this respect, FAAP95 is similar to FANCL7, suggesting that FAAP95 is associated with Fanconi anemia.

Figure 2: Nuclear localization of FAAP95 depends on FANCA.

(a) Immunoprecipitation (IP)-coupled western-blot analysis showing the presence of FAAP95 and its associated complex in both nuclear and cytosolic extracts of HeLa cells. The amount of FAAP95 is too low to detect by direct immunoblotting, unlike that of the other two Fanconi anemia proteins (FANCA and FANCL). BLM (a DNA helicase) and caspase 3 were analyzed as markers for the nuclear (NE) and cytosolic extracts, respectively. (b) Immunoprecipitation-coupled western-blot (IP-western) analysis showing the presence of FAAP95 and its associated FANCL in the cytosolic extract of a cell line defective in FANCA. On complementation of the same cell line by exogenous FANCA ('WT'), both proteins are detected in the nuclear extract (NE). HeLa cells were analyzed as a control. A control experiment is shown in Supplementary Figure 2 online.

The gene encoding FAAP95 is localized on the X chromosome (Xp22.31); therefore, individuals affected with Fanconi anemia with mutations in this gene should all be males. Cells from such individuals should also show defective monoubiquitination of FANCD2 on the basis of the involvement of the core complex in this process and the results of our short interfering RNA (siRNA) experiments (Fig. 1d). Of the three Fanconi anemia complementation groups whose underlying genes have not been identified (FA-B, FA-I and FA-J), only individuals with FA-B (individuals HSC230 and EUFA178) met these two criteria. FAAP95 protein was undetectable in an analysis of lymphoblastoid cell lines from these individuals, indicating that the gene encoding this protein may be FANCB (Fig. 3a).

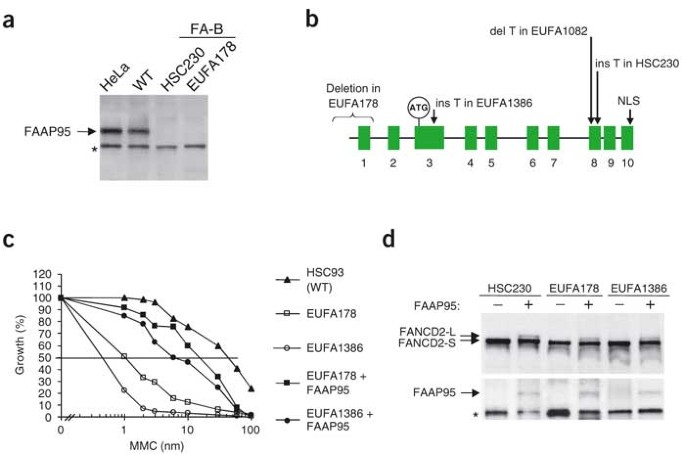

Figure 3: Evidence of a genetic defect in FAAP95 in individuals with FA-B.

(a) Immunoprecipitation-coupled western-blot (IP-western) analysis showing the absence of FAAP95 in whole-cell lysates from two available cell lines from individuals with FA-B, individuals HSC230 and EUFA178. HeLa cells and a lymphoblastoid cell line from a normal individual (WT) were analyzed as controls. The asterisk indicates a nonspecific band. (b) Genomic structure of FAAP95 with ten exons. The approximate locations of the translation start in exon 3 and the bipartite NLS consensus sequence are indicated. The nature and approximate locations of the mutations found in four individuals with Fanconi anemia are also indicated. Drawing is not to scale. (c) Complementation of the cellular Fanconi anemia phenotype after transfection with cDNA encoding FAAP95. Data are corrected for cellular sensitivity to MMC. The data shown are representative of several independent experiments with the same results. WT, wild-type. (d) Complementation of defective monoubiquitination of FANCD2 by transfecting cDNA encoding FAAP95 into the indicated cell lines from individuals with FA-B.

The sequence of the region encoding FAAP95 in HSC230 cells showed a frameshift mutation (1838insT) in exon 8, resulting in a premature stop codon upstream of the NLS consensus sequence (Fig. 3b). No cDNA could be amplified by RT-PCR from individual EUFA178, owing to a deletion of 3,314 bp (10693del3314) that included the promoter region and exon 1. We selected two other individuals (individuals EUFA1082 and EUFA1386) as candidates for FA-B on the basis of their exclusion from most of the other complementation groups, their inability to monoubiquitinate FANCD2 and their male gender. We found frameshift mutations in both individuals, 1650delT (exon 8) in individual EUFA1082 and 811insT (exon 3) in individual EUFA1386 (Fig. 3b), both of which lead to early stop codons upstream of the NLS.

In addition, we transfected lymphoblasts from individuals with FA-B with cDNA encoding FAAP95 and found that the abnormal phenotypes associated with Fanconi anemia, hypersensitivity to mitomycin C (MMC) and monoubiquitination of FANCD2, were both restored to normal (Fig. 3c,d and Supplementary Fig. 3 online). These data proved that the gene encoding FAAP95 is the gene associated with FA-B; therefore, we named the gene FANCB.

Because X-linked inheritance has not been reported in Fanconi anemia, we tested the mothers and grandmothers of the affected males to determine whether they carried the mutations (see Fig. 4 for the pedigrees of the families studied). The mothers of individuals EUFA178 and EUFA1386, and a healthy sister of EUFA178, carried the mutations (Fig. 5). The mutations were not found in the grandmothers or mothers of individuals EUFA1082 and HSC230. These findings suggest that the mothers (of individuals HSC230 and EUFA1082) or a grandparent (of individuals EUFA178 and EUFA1386) may have been germline mosaics for these mutations. Alternatively, a de novo mutation may have occurred after fertilization in these individuals.

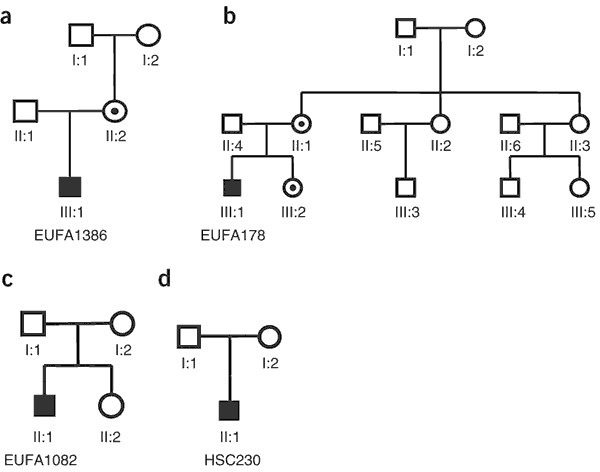

Figure 4: Pedigrees of the four families with FA-B.

(a) Family EUFA1386; the proband is individual III:1, and individual II:2 (also called individual EUFA1387) is a carrier. (b) Family EUFA178; the proband is individual III:1, individuals III:2 (EUFA179) and II:1 (EUFA181) are carriers and individuals II:3 and III:5 are possible carriers. (c) Family EUFA1082; the proband is individual II:1. (d) Family HSC230; the proband is individual II:1. Filled symbols, individuals with FA-B; dotted symbols, carriers of a FANCB mutation.

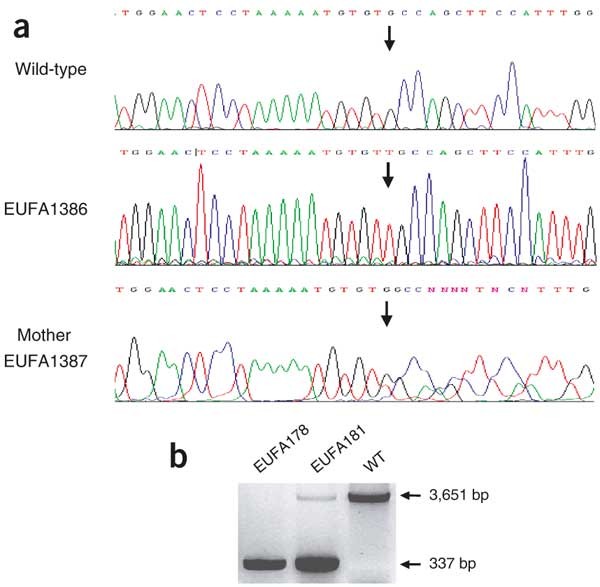

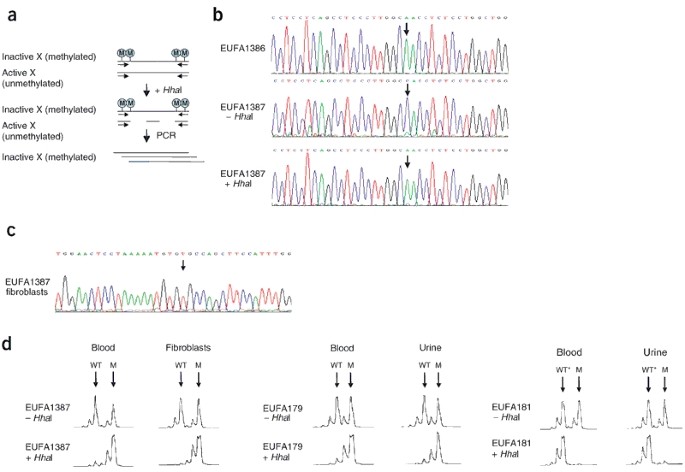

Figure 5: Hemizygosity and heterozygosity of mutations in FANCB.

(a) Partial sequence of exon 8 of FANCB in a normal individual (wild-type), individual EUFA1386 and his mother, individual EUFA1387, showing the 811insT mutation (arrows) in a hemizygous (EUFA1386) and heterozygous (EUFA1387) state. (b) A deletion of 3,314 bp spanning the promoter region and exon 1 is present in individual EUFA178 and his mother, individual EUFA181, generating a 337-bp product; by contrast, a control individual (WT) does not show this mutation, leading to a 3,651 bp product.

In adult females, most genes on one of the X chromosomes are inactive owing to hypermethylation of their promoter9. This X inactivation occurs early in embryogenesis and is randomly determined. Once inactivated, the inactive X remains clonally persistent10. As a result, ∼50% of cells in females have an active paternal X chromosome, whereas the other 50% have an active maternal X chromosome11,12. However, FANCB is situated in a region where ∼60% of the genes escape inactivation and are expressed biallelically13,14. To examine whether FANCB escapes X inactivation, we assessed the methylation status of the gene, which is known to be correlated with silencing15.

We analyzed the methylation state of a CpG island in FANCB using the methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme _Hha_I (Fig. 6a). Without _Hha_I digestion, the amplified fragment showed mainly the wild-type allele (Fig. 6b). As the polymorphism is situated in a CpG island, the asymmetry of this PCR was presumably caused by a higher amplification efficiency of the unmethylated sequence as compared with the methylated sequence. After _Hha_I digestion, however, only the mutated allele was amplified, indicating that this allele was inactive (methylated), whereas the wild-type allele was completely active (unmethylated). In addition, direct RT-PCR amplification of mRNA from fibroblasts of individual EUFA1387 (mother of individual EUFA1386) yielded product from only the wild-type allele (Fig. 6c). These results indicate that FANCB is subject to total inactivation by methylation and that inactivation seems to be completely skewed towards the mutated allele.

Figure 6: FANCB is subject to X inactivation that is skewed towards the mutated allele in heterozygous carriers of the FANCB mutation.

(a) Strategy for detecting the methylated (inactive) allele of FANCB and AR. CpG islands are subject to methylation through the process of X inactivation. AR has two CpG islands, whereas FANCB has only one. Digestion with the restriction enzyme _Hha_I, which digests only unmethylated DNA, consequently allows amplification of a fragment from a methylated (functionally inactive) allele in a PCR reaction. (b) A single-nucleotide polymorphism (A/C) present in FANCB was used to distinguish between the mutated and wild-type alleles in the heterozygous carrier EUFA1387, mother of individual EUFA1386. Individual EUFA1386, has an adenine at the polymorphic site, which is linked to the mutation. Individual EUFA1387 has a cytosine, with a weak adenine signal underneath. After digestion with _Hha_I, only the mutated FANCB allele is amplified, indicating that all wild-type FANCB allele sequences are unmethylated. (c) RT-PCR analysis of FANCB mRNA of fibroblasts from individual EUFA1387, showing expression of only the wild-type FANCB allele. Arrow indicates the position where, in the mutant sequence, a thymine is inserted (Fig. 5). (d) The polymorphic CAG repeat in the AR promoter was used to examine skewed inactivation of FANCB in the indicated tissues from mutation carriers. The AR alleles are linked to the wild-type (WT) allele or the mutated (M) FANCB allele as observed in affected individuals. _Hha_I treatment typically left the mutation-linked allele intact, indicating the methylated (inactive) status of the chromosome containing the FANCB mutation. The apparent discrepancy in individual EUFA181 (WT*) is explained by the occurrence of single recombination event between FANCB and AR (Supplementary Fig. 4 online).

To examine whether there was skewed X inactivation in other tissues of the mother, we analyzed the methylation status of the androgen receptor gene (AR) promoter using a highly polymorphic CAG repeat. AR is located on Xq11.2–12, ∼40 cM from FANCB, and is subject to X inactivation16. Results showed that X inactivation was skewed towards the mutant chromosome in blood and skin fibroblasts of the mother. We observed a similar situation in cells from both female carriers in the family of individual EUFA178 (Fig. 6d). The lack of a correlation with the mutant chromosome seen in individual EUFA181 was explained by a single recombination event between FANCB and AR (Supplementary Fig. 4 online).

The extreme under-representation of somatic cells expressing the mutated FANCB allele in these three female carriers is not completely unexpected. Individuals with Fanconi anemia are typically growth retarded, and cultured Fanconi anemia cells are prone to apoptosis17. Thus, Fanconi anemia cells in a mosaic individual probably have a proliferative disadvantage. Because X inactivation takes place early in embryogenesis, selection over many subsequent cell generations may lead to almost complete overgrowth by normal cells. The female carriers studied (aged 12, 29 and 43 y) were healthy and showed no Fanconi anemia–like symptoms, and their T cells responded normally to challenge with MMC without any sign of mosaicism (data not shown). We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that a few Fanconi anemia–like cells are present in these carriers. Because such cells are thought to be prone to malignant transformation (as in individuals affected with Fanconi anemia), monitoring such individuals for the occurrence of malignancies should be considered.

Similarly skewed X inactivation has been observed in some other X-linked diseases, such as fragile X and Wiskott-Aldrich syndromes; however, cases have been described in which X inactivation is skewed towards the wild-type allele, causing symptoms of disease in female carriers18,19. In female carriers of the FANCB mutation, there may be a strong selective force against the occurrence of such a situation. But the predictive value of our data is limited because we studied only three cases. Therefore, features of disease in carriers of the FANCB mutation cannot yet be excluded. In cases that are diagnosed in the future, assessment of skewed X inactivation is recommended, preferably in various tissues, as reported here.

Identification of an X-linked gene associated with Fanconi anemia has important implications for the diagnosis and genetic counseling of families in which only male children are affected with the disease. Such families should be tested to determine if they are affected with FA-B, although it is rare. In families with FA-B, mutation screening can identify sisters and maternal aunts as carriers of the mutation who, if they test positive, have a 50% chance of conceiving an affected son or carrier daughter, irrespective of their partners.

FANCB was proposed to be BRCA2 on the basis of a hypomorphic mutation in BRCA2 detected in the HSC230 cell line5; however, no complementation of HSC230 by BRCA2 has been reported. In addition, no BRCA2 mutation has been detected in another known FA-B cell line, EUFA178 (ref. 4). Furthermore, cells with defective or depleted BRCA2 show normal monoubiquitination of FANCD2, unlike FA-B cells, which show defective FANCD2 monoubiquitination. The identification of FANCB resolves this ambiguity.

Because only a single active copy of FANCB is present in the human genome, this gene may be a potentially vulnerable component of the cellular machinery that maintains genomic integrity. Although germline mutations in FANCB are exceedingly rare, somatic FANCB mutations are likely to occur at the average spontaneous mutation rate. This may be important, because mutational inactivation of only one FANCB allele is sufficient to generate a Fanconi anemia–like cellular phenotype. The occurrence of such Fanconi anemia–like cells may contribute to oncogenesis, similar to a previously proposed mechanism20,21 on the basis of epigenetic silencing of FANCF in a subset of sporadic malignancies. Similar to what was suggested for individuals with _FANCF_-silenced tumors20,21, individuals with _FANCB_-mutated tumors might be effectively treated with crosslinking chemotherapeutic agents such as cisplatin.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Genetics website.