Regulation of immunological homeostasis in the respiratory tract (original) (raw)

Respiratory epithelial-cell surfaces present a large fragile interface with the external environment, which is exposed continuously to a broad range of antigens during respiration. Maintenance of local immunological homeostasis and hence the integrity of these gas-exchange surfaces stretches the discriminatory powers of the immune system to their limits, as incoming antigens are dominated by highly immunogenic but harmless proteins of plant and animal origin which, if they evoked efficient adaptive immune responses, would doom the host to premature death from chronic airway inflammation. The balancing act that the respiratory mucosal immune system must perform involves discrimination of this background antigenic noise from the much rarer signals transmitted by pathogen-associated antigens. Not only must the immune system deal with this low signal-to-noise ratio problem, but having selected antigens for T-cell priming, it must tightly regulate ensuing T-cell memory responses to minimize damage to local epithelial-cell surfaces. This is of particular importance in relation to alveolar gas-exchange surfaces, as these tissues contain the largest vascular bed in the body and function as a magnet for circulating memory T cells.

The key mechanisms through which the local immune system performs this balancing act is the theme of this Review. In particular, we focus on the microanatomical organization of local elements of the innate and adaptive immune systems, the cellular dynamics of immune induction in this microenvironment and the roles of individual cell types in fine tuning local immune responses. Important areas not addressed in this Review owing to space limitations include the role of neuropeptides in local immunoregulation, control of wound healing and/or tissue repair in response to chronic inflammation and the potential future impact of advances in stem-cell biology.

Organization of the immune system in the lungs

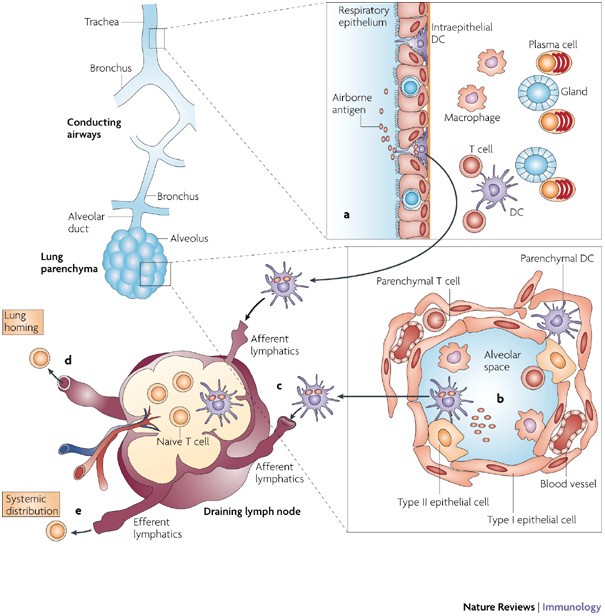

The lungs can be divided into two functionally distinct compartments: the conducting airways overlayed by mucosal tissue, and the lung parenchyma, which comprises thin-walled alveoli that are specialized for gas exchange (Fig. 1). Distinct populations of immune cells reside in these adjacent areas, reflecting the differing functions of local tissues, as well as the differing levels of exposure to airborne antigens throughout the respiratory tree.

Figure 1: Antigen uptake and migratory patterns for immune induction in the lungs.

Local immune cells in the two lung compartments showing capture of airborne antigens and subsequent recognition by T cells in the draining lymph nodes. Luminal antigens are sampled by dendritic cells (DCs) that are located within the surface epithelium of the bronchial mucosa (a) or in the alveoli (b). Antigen-bearing DCs upregulate CC-chemokine receptor 7 and migrate through the afferent lymphatics to the draining lymph nodes and present antigenic peptides to naive antigen-specific T cells (c). Activated T cells proliferate and migrate through the efferent lymphatics and into the blood via the thoracic duct. Depending on their tissue-homing receptor profile, effector T cells will exit into the bronchial mucosa through postcapillary venules in the lamina propria or through the pulmonary capillaries in the lung parenchyma (d), or disseminate from the bloodstream throughout the peripheral immune system (for example, to other mucosal sites) (e).

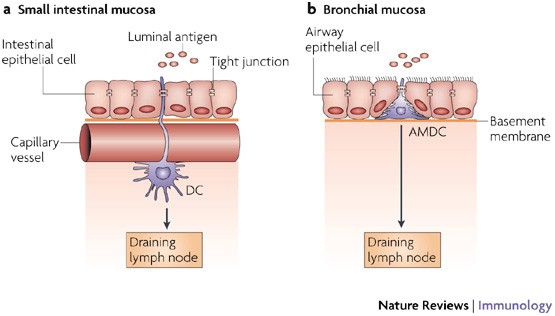

Conducting airways. The respiratory epithelium of the airway mucosa comprises ciliated cells and secretory goblet cells that, together with locally produced secreted IgA, provide mechanisms for mucociliary clearance of inhaled antigens. The mucosa contains dense networks of dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages that develop early in life1. Within these dense networks, the DC pool is composed of both myeloid DCs and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), but the myeloid DC subset generally dominates, particularly in the airway mucosa2. Resident airway mucosal DCs (AMDCs) are specialized for immune surveillance by antigen acquisition but lack the ability to efficiently present antigen3. They are strategically positioned for antigen uptake both within and directly beneath the surface epithelium, and extend protrusions into the airway lumen4, similar to what has been reported for DCs in intestinal tissue5 (Fig. 2). This suggests that AMDCs can sample directly from the airway luminal surface through the intact epithelium4. T cells are also found in relatively high numbers in the mucosa, both intraepithelially and within the underlying lamina propria (Fig. 3). As in the gut, most intraepithelial T cells express CD8, whereas CD4+ T cells are more frequently found in the lamina propria. Both subsets mainly have an effector- and/or memory-cell phenotype, as defined by their expression of CD45RO. The lamina propria also contains mast cells (Box 1) and plasma cells (mainly producing polymeric IgA) and some scattered B cells. Aside from their central role in antibody production, it is possible that B cells also contribute to local antigen presentation, given the recent demonstration of such a function for B cells in the lymph nodes that drain the lungs6.

Figure 2: A model for antigen sampling at mucosal sites.

a | Resident dendritic cells (DCs) that are located beneath the microvasculature in the small intestinal villi extend cellular projections around the subepithelial vessels and up between the intestinal epithelial cells5. These cellular protrusions enable them to directly sample antigens on the luminal side. The DCs preserve the integrity of the epithelial-cell barrier by expressing tight-junction proteins. After antigen uptake the DCs upregulate CC-chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7), which allows them to migrate to the draining lymph nodes. b | Analogous to intestinal resident DCs, resident airway mucosal DCs (AMDCs) that are situated within the epithelial compartment in the respiratory mucosa (both in rodents and humans) extend cellular projections into the airway lumen. Although direct evidence for the uptake of luminal antigens by AMDCs is still lacking, this model provides a plausible mechanism for continuous immune surveillance of intact respiratory mucosal surfaces.

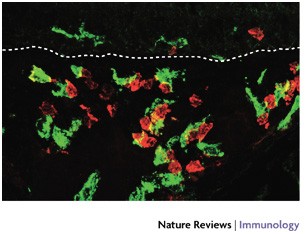

Figure 3: Distribution of DCs and T cells in the tracheal mucosa.

Cryosection from a rat trachea (1 μm optical section) showing immunofluorescence staining of dendritic cells (DCs; MHC class II stained green) and T cells (CD2 stained red). Note that most of the T cells are in close contact with DCs. The dotted line represents the basement membrane of the surface epithelium. Magnification ×600.

In addition to effector-cell populations, the airway mucosa also contains potential inductive sites known as bronchial-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT). Classical BALT comprises discrete lymphoid-cell aggregates underlying a specialized epithelium, analogous to tonsillar tissue and Peyer's patches. The presence of BALT differs between species and its importance in adult humans has been questioned, however, BALT is common in young children and mostly contains isolated lymphoid follicles (I. Heier, K. Malmström, A. S. Pelkonen, L. P. Malmberg, M. Kajosaari, M. Turpeinen, H. Lindahl, P. Brandtzaeg, F.L.J. and M. J. Mäkelä, unpublished observations). Importantly, the inducible BALT from mice that lack other organized lymphoid tissue can generate protective immunity against pathogens, such as influenza virus7. This suggests that BALT may have a significant role in local immunological homeostasis within the respiratory tract early in life when important elements within central lymphoid structures are functionally immature.

Parenchymal lung. Progressive branching of the bronchi gives rise to bronchioles that extend to alveolar ducts that further branch into blind-ended alveolar sacs (Fig. 1). The alveoli are separated by thin walls of interstitium containing pulmonary capillaries that are in close contact with the alveolar space, and some stromal cells (Fig. 1). Immune cells in the lung parenchyma are located both above the alveolar epithelium in the terminal airways and in the underlying parenchyma. Under steady-state conditions, the leukocyte population in the alveolar space is dominated by alveolar macrophages (more than 90% of the total cell population), the remainder being mainly DCs and T cells. The lung parenchyma also contains scattered macrophages, DCs and T cells, as well as B cells and mast cells, but no plasma cells. In addition, large numbers of T cells are sequestered in the vascular bed of the lung parenchyma. The contribution of this large population of cells to local immunological homeostasis is unclear, but many appear to be 'anergized' and might represent end-stage post-activated memory cells en route for removal through the liver or the mucociliary elevator8.

Immune induction in the lung: cellular dynamics

Respiratory mucosal surfaces, particularly in the upper conducting airways, are chronically exposed to myriad non-pathogenic environmental antigens. To protect against the potential immunopathological consequences of continuously responding to these ubiquitous stimuli, the local 'default' immune response takes the form of non-inflammatory, low-level T helper 2 (TH2)-cell immunity3 and/or a form of T-cell-mediated immunological tolerance9,10. This response pattern reiterates that of the chronically stimulated gastric mucosa11. The mechanism(s) underlying this protective default are only partially understood, but appear to be under the control of local DC subsets3,10,12,13,14. Moreover, there is an additional level of backup control to regulate the intensity of 'breakthrough' memory T-cell responses, which evade this protective default, in the form of the potent T-cell-inhibitory activity of lung macrophages8,15,16. This mechanism is particularly active in the lung parenchyma through the immunosuppressive functions of resident alveolar macrophages17,18, providing a last line of defence for alveolar gas-exchange surfaces against T-cell-mediated inflammation.

The identification of potentially pathogenic antigens is facilitated through pattern-recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), that are expressed by the network of sentinel AMDCs (Table 1), and results in effective bypassing of the TH2-cell default and the subsequent generation of effector memory responses against these antigens. It is of interest to note, however, that some (probably low) level of TLR stimulation of DCs in the airway mucosa appears to be obligatory to enable initial recognition per se of inert inhaled antigens19. Qualitative and quantitative aspects of the ensuing immune responses to such antigens (including tolerance induction) might be determined in part by the level of co-exposure to TLR-stimulatory agents, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS)20, which are ubiquitous in ambient air.

Table 1 TLR expression on human lung DCs

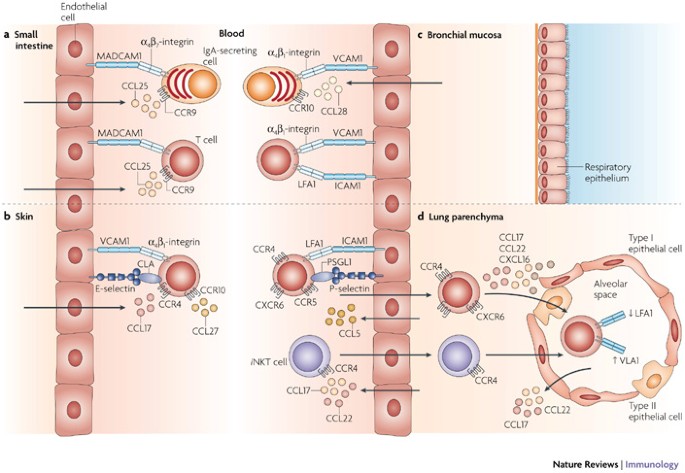

Tissue-specific lymphocyte homing. As noted above, surveillance of airway surfaces for these different classes of antigen is carried out primarily through the AMDC network, which continuously shuttles incoming antigens to regional lymph nodes (RLNs), which are the primary sites for the induction of immunological memory against inhaled antigens (Fig. 1). Following activation, subsequent to their migration to the RLNs, these DCs develop a potent capacity to prime naive T cells and initiate immune responses. Moreover, the resulting memory T cells have an enhanced capacity for selective migration back to the original challenge site — the concept of tissue-specific homing21. Whereas naive T cells express adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors that restrict their migration principally (but not entirely22) to organized lymphoid tissue, activated memory T cells downregulate these lymphoid-tissue-homing receptors and upregulate tissue-specific adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors that target their migration to non-lymphoid tissues21. This imprinting of tissue-homing properties is best described for the gut and skin. Priming of T and B cells in Peyer's patches and mesenteric lymph nodes preferentially induces the expression of α4β7-integrin and CC-chemokine receptor 9 (CCR9)23,24, whereas T cells that are primed in peripheral lymph nodes upregulate cutaneous leukocyte antigen, CCR4 (Ref. 25) and CCR10 (Ref. 26) (Fig. 4). Importantly, recent results suggest that antigen-presenting DCs process and 'interpret' locally produced metabolites to programme tissue-specific lymphocyte homing. In the case of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), resident DCs metabolize vitamin A to retinoic acid, which stimulates α4β7-integrin and CCR9 expression by T cells23; and in the skin, local DCs use metabolites of vitamin D3 to programme T cells in RLNs for epidermotropism27. Moreover, DCs resident in GALT that metabolize vitamin A also induce the generation of gut-homing IgA-secreting B cells28.

Figure 4: Trafficking of lymphoid cells mediated by specific adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors.

Recruitment of lymphoid cells into target tissues requires specific chemokine recognition and adhesion-receptor engagement. a | IgA-secreting cells and T cells that are primed in Peyer's patches and mesenteric lymph nodes preferentially express α4β7-integrin and CC-chemokine receptor 9 (CCR9). Endothelial cells of postcapillary venules in the intestinal mucosa constitutively express ligands for α4β7-integrin and CCR9, namely mucosal addressin cell-adhesion molecule 1 (MADCAM1) and CC-chemokine ligand 25 (CCL25), respectively, which allow lymphoid cells that are induced in intestinal lymphoid tissue to enter this mucosal effector site. b | T cells that are primed in peripheral lymph nodes lack intestinal homing receptors, but express cutaneous leukocyte antigen (CLA), α4β1-integrin, CCR4 and CCR10. These T cells are targeted to skin tissues that express ligands for these receptors (E-selectin, vascular cell-adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1), CCL17 and CCL27, respectively) and cannot enter the intestinal mucosa. c | Distinct homing phenotypes for lymphoid-cell trafficking to the respiratory tract have yet to be defined, but recent information suggests that activated lymphoid cells that are induced by respiratory antigens express distinct phenotypes and lack intestinal-homing molecules. IgA-secreting cells that home to the bronchial mucosa express α4β1-integrin, whereas T cells express α4β1-integrin and lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA1), which correspond with their counterparts VCAM1 and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1), respectively, that are constitutively expressed on the vessel wall in the bronchial mucosa. The α4β1-integrin–VCAM1 interaction is also crucial for lymphocyte homing to bronchial-associated lymphoid tissue, which is unique among secondary lymphoid tissues. IgA-secreting cells that traffic to the bronchial mucosa also express CCR10 and the ligand CCL28 is produced locally. The chemokine receptors that are involved in T-cell homing to the central airways are less well defined. d | The expression of LFA1, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL1) and CCR5 appear to be important for T cells to enter the lung parenchyma, whereas their further migration into the alveoli depends on expression of multiple chemokine receptors. Furthermore, their retention in the airways is associated with downregulation of LFA1 and upregulation of α1β1-integrin (also known as VLA1). Recruitment of invariant natural killer T (_i_NKT) cells to the lung parenchyma depends on CCR4, but the adhesion molecules involved in _i_NKT-cell-trafficking have not been defined.

Lymphocyte homing to the lungs. Although there are studies that suggest that tissue-specific T-cell homing is also operative in the respiratory tract, distinct homing phenotypes have yet to be defined29. Moreover, cell recruitment to the lungs is unique in that it has two separate circulatory systems — the bronchial arteries from the systemic circulation that nourish the bronchial wall and the low-pressure pulmonary system that circulates through the lung parenchyma. The mucosa of the central airways is part of the common mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), a system that integrates the immune responses of distinct mucosal tissues. However, although MALTs from different sites share several properties (such as IgA responses), there are distinct tissue-trafficking patterns for both B and T cells that depend on their site of induction (Fig. 4). For example, plasma-cell precursors that are primed in respiratory-tract lymphoid tissues that home to the tracheal and bronchial mucosa express only low levels of the gut-homing molecules α4β7-integrin and CCR9, but express high levels of α4β1-integrin and CCR10 (Ref. 24). Importantly, the counterparts of α4β1-integrin and CCR10, vascular cell-adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1) and CC-chemokine ligand 28 (CCL28), respectively, are constitutively expressed by airway mucosal endothelial cells24. Lung T cells also express a phenotype that is distinct from gut-homing T cells30.

In the lung parenchyma, leukocytes migrate mainly through pulmonary capillaries. As a result, the concept of a coordinated multistep migratory process through the postcapillary venules that occurs in most tissues is not always required for extravasation in the lungs. Although the recirculation of memory T cells through the lung parenchyma appears to be less tightly regulated than in the intestine, several lines of evidence suggest that the egress of T cells into the lung parenchyma is, in some cases, a regulated process. In human and mouse lungs, it has been shown that memory CD8+ T cells that are specific for respiratory viruses selectively accumulate in the lung parenchyma29. Under non-inflammatory conditions, endothelial cells in the pulmonary vasculature express intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) and P-selectin, but not VCAM1. Galkina and co-workers31 showed that preferential vascular retention and egress of effector CD8+ T cells to the normal mouse lung was mediated by lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA1)–ICAM1 and CCR5–CCR5-ligand interactions. Also, inhibition of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL1), which binds P-selectin, reduced the number of T cells in the alveoli and lung parenchyma. Kallinich et al.32 have shown that CXC-chemokine receptor 6 (CXCR6) was strongly expressed by human T cells that were obtained by bronchoalveolar lavage. High levels of its ligand, CXC-chemokine ligand 16 (CXCL16), were also detected in the parenchyma, indicating that the CXCR6–CXCL16 pair could be involved in tissue-specific lung homing33. Influenza-virus-specific CD8+ T cells that accumulate in the lung tissue of mice express the collagen-binding α1β1-integrin (also known as VLA1), and blocking this integrin led to a reduction in antigen-specific T cells, most dramatically in the airways34. Moreover, the level of LFA1 expression is markedly reduced on airway T cells compared with parenchymal T cells35. These observations suggest that selective expression of integrins might be an important mechanism for the retention of T cells within the airways, at least in mice.

In summary, the general immunological milieu in healthy lungs appears to be equivalent to that of a 'low-level alert' status, in which efficient surveillance mechanisms are maintained for discrimination between trivial and potentially pathogenic antigens, whereas the capacity for local mobilization of strong immune effector mechanisms remains tightly constrained. This scenario limits the risk for damage to host lung tissues by unnecessary immune responses to non-pathogenic antigens or excessively aggressive memory T-cell responses against pathogens. Various cell populations contribute to the overall maintenance of local immunological homeostasis within the respiratory tract, and in some cases exhibit functions that appear to be specifically adapted to the unique local tissue microenvironments. Particularly notable examples are discussed in the next section of this Review.

Specialized roles of individual cell types

There are a number of individual cell types that have specialized roles in the fine tuning of immunological homeostasis in the lungs. In this section, we cover the most relevant cell types, although others, such as mast cells (Box 1) and natural killer (NK)-cell populations (Box 2) are also important.

Lung DC populations: 'gatekeepers' of local adaptive immunity. Resident lung DCs share many phenotypic traits with DCs from other non-lymphoid tissues, and the typical profile includes high expression of MHC class II and CD205, together with low expression of CD8, CD40, CD80 and CD86 (Refs 3, 36). In the steady state, they are specialized for antigen uptake and processing but lack the capacity for efficient antigen presentation, an attribute they normally develop only after migration to the RLNs3. However, in some circumstances, typified by atopic asthma in which lung DCs have a key role in the associated airway inflammation37, lung DCs can transiently develop potent antigen-presenting cell (APC) activity in situ (see below).

Several distinct subpopulations of lung DCs have been identified38,39,40, but, until comparatively recently, the principal focus of research had been directed towards the myeloid DC subset, in particular, that found within the airway mucosa. A unique attribute of AMDC networks is their extremely high turnover rate in the steady state41 and their capacity for further rapid upregulation in the face of local inflammatory challenge3. Notably, DC precursor recruitment following bacterial challenge exhibits kinetics that are comparable to neutrophils4,42, and only slightly less-rapid response patterns are evident following challenge with viruses and protein-recall antigens43. It is noteworthy that the recruitment of AMDCs at baseline and in response to bacterial stimuli is CCR1 and CCR5 dependent, whereas corresponding responses to virus or protein-recall antigen use alternative chemokine ligand–receptor combinations43,44. In addition, experiments in CCR7-deficient mice have demonstrated a key role for CCR7 in the baseline emigration of antigen-bearing lung DCs to RLNs13, further emphasizing the heterogeneity of chemokine usage patterns in relation to the fine control of local DC-mediated immune surveillance; inhalation tolerance to a non-pathogenic antigen could not be induced in the CCR7-deficient mice13. It is pertinent to note that the current focus on these highly dynamic AMDC subsets has so far ignored the potential role of a key subset (comprising 15% of AMDCs) of AMDCs with half-lives of more than 10 days41.

There is increasing interest in the role of the pDC subset in the lungs, particularly in view of recent findings that implicate these cells in tolerance induction to inhaled antigen12. A further indication of the potentially important functions of the pDC subset is their distinct pattern of TLR expression (Table 1) and accompanying high capacity to produce interferon-α (IFNα) in response to microbial stimuli45,46. However, unlike myeloid DCs, human pDCs have poor APC activity45 and there is no evidence for pDC migration out of lung tissues; rather, they behave as lymphocytes, entering lymphoid organs from the blood and responding locally to inflammation. Although resting pDCs are poor T-cell stimulators, mature pDCs from mice47 and humans48 can present antigen to CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells in vitro. In vivo, T-cell priming might be limited to CD8+ T cells in mice39, but pDCs might stimulate CD4+ T cells in some lymphoid organs49. These findings are collectively consistent with the perceived primary role of pDCs in antiviral immunity, although their capacity for CD4+ T-cell activation requires more detailed characterization.

Lung epithelial cells: the first line of defence. Airway epithelial cells (AECs) have key roles in the regulation of lung homeostasis. As well as serving an important barrier function in the exclusion of incoming environmental antigens, AECs secrete into the overlying fluid a range of regulatory and effector molecules that are involved in front-line defence against pathogens (Table 2). In addition, they have broad-ranging roles in the modulation of the activity of adjacent cell populations. Relevant functions include: modulation of airway smooth-muscle activity50; production of nitric oxide, which is a potent inhibitor of the functional activation of lung DCs15 and memory T cells16; amplification of host responses to microorganisms through the secretion of chemokines and cytokines51,52, in particular, type I and III IFNs53,54; production of mediators such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and ICAM1, which enhance the local survival of recruited inflammatory cells55; regulation of respiratory-tract DC functions by growth factors such as GM-CSF56; and modulation of airway B-cell accumulation and/or activation57. In addition, the diverse array of receptors that are expressed by AECs enables them to respond dynamically to incoming stimuli, including allergens, microorganisms and particulate material, and to thus adjust their mediator-production profiles to meet individual threats.

Table 2 First-line defence molecules produced by airway epithelial cells (AECs)

Lung macrophages: multifaceted effector and modulatory roles. Macrophages have a central role in the maintenance of immunological homeostasis and host defence, and in the lungs the key population is composed of alveolar macrophages. In the steady state, the principal function of alveolar macrophages is phagocytosis and sequestration of antigen from the immune system to shield local tissues from the development of specific immune responses58. Alveolar macrophages have been shown to take up most of the particulate material that is delivered intranasally, but they do not migrate to RLNs, nor are they considered to have a significant role in antigen presentation17,59. Alveolar macrophages also actively suppress the induction of adaptive immunity, as confirmed by studies showing that the use of clodronate-filled liposomes to deplete alveolar macrophages in vivo rendered rodents susceptible to T-cell-mediated inflammatory responses to otherwise harmless inhaled antigens18. The suppressive effects of alveolar macrophages were initially attributed to the direct suppression of T cells by nitric oxide and/or mediators such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), prostaglandins and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ). However, lung DCs clearly have enhanced APC function in alveolar-macrophage-depleted rodents, indicating that alveolar macrophages might suppress APC function rather than directly suppressing T cells60. More recently, it has been shown that alveolar-macrophage depletion results in increased numbers of DCs in alveolar spaces and increased uptake of particles by DCs, resulting in increased migration to RLNs59. These studies demonstrate a probable role for alveolar macrophages in the steady-state regulation of DC migration and localization.

Further highlighting the complexities of these regulatory mechanisms, it has also been shown that under homeostatic conditions, alveolar macrophages closely adhere to AECs, inducing the TGFβ-dependent expression of αvβ6-integrin by AECs. The binding of latent TGFβ to αvβ6-integrin on AECs results in the local activation of TGFβ in close proximity to alveolar macrophages. Activated TGFβ binds to alveolar macrophages and induces suppression of cytokine production61,62. Mice deficient in αvβ6-integrin have constitutively activated alveolar macrophages63; this mechanism seems to be unique to the lungs and exemplifies the specialized modulation of macrophage function by the local microenvironment to meet the needs of the tissue.

Although resting alveolar macrophages are normally maintained in a quiescent state and produce small amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, they maintain the capacity to be activated in response to extrinsic and intrinsic stimuli, including cytokines, microorganisms and particulate material. The activation of alveolar macrophages results in a shift in their functional capacity to that of efficient effector cells that participate in phagocytosis, killing64 and coordination of the innate immune response65. TLR ligation on alveolar macrophages results in their detachment from AECs, loss of αvβ6-integrin expression and, consequently, loss of the influence of the αvβ6-integrin–TGFβ axis over local homeostasis62.

The turnover of alveolar-macrophage populations is normally extremely slow relative to the adjacent DC populations. In the steady state, alveolar macrophages are largely renewed by local precursor-cell proliferation, but during inflammation renewal essentially occurs via incoming monocytes and is regulated through the CCL2–CCR2 axis66. It is worth noting that the functional phenotype of recently recruited monocytes contrasts markedly with that of resident alveolar macrophages; in particular, the monocytes can function as effective APCs before their maturation into immunosuppressive alveolar macrophages, which occurs over a period of days67. Their recruitment thus opens a transient 'window' for T-cell responsiveness in the peripheral lung. Notably, this monocyte maturation process can be delayed by GM-CSF, thus prolonging the window for the local induction of T-cell immunity15. In addition, the immigrating monocytes invariably include immature DCs, which, under the influence of GM-CSF, will also enhance T-cell responsiveness during this period68.

Regulatory T cells: sheet-anchoring local adaptive immunity. Forkhead box P3 (FOXP3)+CD4+CD25+ regulatory T (TReg) cells are central to the control of peripheral T-cell responses69 and use various mediators for this purpose, including IL-10 and/or TGFβ, and possibly nitric oxide70. In relation to the lung, they are believed to have key roles in protection against the inflammatory sequelae of airway infections, exemplified by viral bronchiolitis, and in protection against the induction and expression of atopic disease. The process of inhalation tolerance, which protects against sensitization (and ensuing IgE production) to aeroallergens is T-cell mediated9, and recent evidence has implicated TReg cells as mediators of this form of tolerance10. The relative importance of antigen-specific versus nonspecific TReg cells in this and related contexts remains unresolved.

TReg cells may also have a central role in controlling the local activation of allergen-specific TH cells that evade tolerance. We have demonstrated that the triggering step in the asthma late-phase response involves cognate interactions between allergen-bearing AMDCs and incoming memory T cells within the airway mucosa, leading to transient upregulation of local APC activity followed by TH-cell activation71. This process and the ensuing airway hyperresponsiveness can be attenuated by TReg cells that are recruited into the airway mucosa following the first wave of inflammation that is triggered by allergen inhalation14, which is consistent with a role for these cells in limiting the intensity and duration of asthma exacerbations. Failure of this TReg-cell mechanism in atopic people who are sensitized to perennial aeroallergens would potentially lead to repeated cycles of TH2-cell-associated inflammation, thus stimulating the tissue repair and/or wound-healing responses, which are the harbingers of the airway-tissue remodelling that is the hallmark of chronic human asthma72.

Of additional interest, steroids that are used in the treatment of human asthma have recently been shown to promote TReg-cell activity in vitro and in vivo73, and this could explain some of the positive effects of inhaled steroids in asthmatics. Moreover, it has also recently been demonstrated that ongoing protection of airway tissues in sensitized animals via TReg cells relies absolutely on continuation of allergen exposure, as withdrawal of stimulation leads to rapid decline in airway TReg-cell numbers and restores susceptibility to the TH2-cell-dependent airway-hyperresponsiveness-inducing effects of aeroallergen challenge14. Whether prolonged stimulation of TReg cells by the continuous therapeutic administration of allergen can eventually exhaust relevant allergen-specific TH2-memory-cell populations remains to be established. Further investigation of this concept and the mechanisms responsible will ultimately guide the development of new therapeutic strategies.

It is also noteworthy that in the setting of TLR-induced activation of DCs, the suppressive role of TReg cells is circumvented, thus enabling the induction of appropriate adaptive immune responses74,75. Reversal of TReg-cell suppression requires TLR-induced IL-6 production, and IL-1 can synergize with IL-6 in this process74,75,76. In situations in which atopic asthma is acutely exacerbated by respiratory infections77, it is plausible that the infection and activation of DCs via pathogen-associated molecular patterns, and the ensuing derailment of TReg-cell control, could be central to triggering the exacerbation of asthma, and this issue merits more detailed investigation.

Recent insights into effector T-cell functions. For the past three decades, the TH1–TH2-cell paradigm has provided the basis for the systematic study of immune regulation. In the context of immunologically related lung diseases, these two sides of the yin–yang dichotomy of TH-cell function have supplied much of the conceptual framework for studies on the pathogenesis of infectious and allergic respiratory diseases, and related drug development. However, it is becoming increasingly evident that TH-cell functions are considerably more complex and heterogeneous than originally envisaged, and underlying concepts are rapidly being revised on several fronts. Two recent developments that are related to T-cell function are of particular relevance to immunoregulation in the lungs.

The first relates to the potential key role of TH17 cells in disease pathogenesis75,76. Differentiation of this T-cell population, which produces large amounts of IL-17, IL-22 and IL-23, is thought to be induced by IL-6, IL-21 and TGFβ in mice75,76 and by the combination of IL-6 and IL-1β in humans78. IL-23, originally thought to have a role in the differentiation of TH17 cells, is now regarded as being important for maintaining TH17-cell immune pathology. IL-22 has been shown to have a crucial role in innate skin immunity by the induction of cyclic AMP and might also have an important role in respiratory-tract immunology. IL-17 is an important cytokine that is involved in the mobilization and generation of neutrophils, and as such might have a pivotal role in pathogen clearance. In relation to the compartmentalization of TH-cell functions, TH1-type cytokines strongly inhibit the development not only of TH2 cells but also of TH17 cells, and TH2-type cytokines (notably IL-4) inhibit the development of both TH1 and TH17 cells75,76,79. The association of IL-17 and neutrophils with more severe forms of immunoinflammatory disease79 leads one to ponder the importance of TH17 cells in the pathogenesis of atopic asthma, particularly as the only T cells that can produce IL-6 appear to be TH2 cells.

Interestingly, the differentiation of TH17 and TReg cells appears to be mutually exclusive75,76. In mice, TGFβ induces the differentiation of both TH17 and TReg cells, however, IL-6 inhibits TReg-cell differentiation and TH17 cells constitute the resultant population. It has been proposed that the reversal of TReg-cell suppressive function that is induced by TLR activation may be a reflection of an increase in TH17-cell differentiation (involving IL-6 and TGFβ) rather than a decrease in the ability for suppression76. However, a different scenario may be that TReg-cell populations (which have reversed suppressive capacity) also undergo proliferation, and once pro-inflammatory cytokine production has sufficiently subsided, there would be an increased pool size of TReg cells readily available to limit immune pathology and act to re-establish steady-state conditions75.

An additional conceptual development that is relevant to this discussion relates to the role of AECs in driving the selection of disease-related TH-cell phenotypes through the expression of potent T-cell modulatory molecules. Notable examples are thymic stromal lymphopoietin, which drives the development of tumour-necrosis-factor-producing 'inflammatory' TH2 cells80, and the IL-17 cytokine family member IL-25, which drives overall TH2-cell differentiation81. In this context, we have recently demonstrated by microarray analysis the differential expression of the IL-25 receptor (known as IL-17RB) in human allergen-specific memory TH2 cells from atopic individuals as part of a large transcriptome that contains multiple previously unrecognized TH2-cell-associated genes82. These findings underscore the potential use of bioinformatics-driven approaches in the identification of covert effector pathways in respiratory inflammatory diseases, and this represents a potentially fruitful avenue for future research.

Conclusions

Although substantial progress has been made in the elucidation of the basic mechanisms that underlie the fine control of immune responses to different classes of inhaled antigens, subsequent translation of these largely experimental findings into the human disease arena remains an elusive goal. The archetypal example of this quandary is atopic asthma, the key manifestations of which can be readily replicated in animal models by deliberately bypassing the fundamental tolerance mechanisms that limit sensitization to non-pathogenic airborne antigens, and can be readily controlled by a range of highly selective TH2-cell antagonists. The surging prevalence of respiratory inflammatory syndromes such as asthma over the past 2–3 decades and the disappointing clinical efficacy of the latest generation of anti-inflammatory drugs developed to treat these diseases attests to the fact that we are still lacking a clear understanding of the key mechanisms that underlie immunoregulation in this microenvironment, and as such, we are in need of new paradigms to drive drug discovery83.

As well as the covert complexity of underlying effector mechanisms, part of the problem may be the limitations that are inherent in modelling what are, in reality, chronic inflammatory diseases in short-term experimental settings. In particular, emerging evidence suggests that primary sensitization to airborne antigens often occurs in infancy when immune functions are (developmentally) attenuated, but may not manifest as clinically relevant airway disease until later in life when immune effector mechanisms in the respiratory tract are fully competent84. Dealing with such subtleties of disease pathogenesis remains a major challenge to progress in this area.