The AVIT protein family (original) (raw)

About 20 years ago, during an analysis of the constituents of the venom of the black mamba, Dendroaspis polylepis, Joubert & Strydom (1980) discovered a small, non‐toxic protein that they named protein A. Ten years later, Schweitz et al. (1990, 1999) tested this protein for activity in various pharmacological assays and found that it stimulated the contraction of the guinea pig ileum at nanomolar concentrations. A small protein was subsequently isolated from the skin secretions of the frogs Bombina variegata and B. bombina, which, by amino‐acid sequencing and complementary DNA cloning, was found to be closely related to protein A from mamba venom (Mollay et al., 1999). Moreover, the ability of this protein to contract the guinea pig ileum was comparable to that of protein A.

Finding closely related proteins in snake venom and frog skin secretions suggested that homologues may also be present in mammals. Indeed, in exon‐trapping experiments, an exon had been isolated from mouse embryonic stem cells (Nehls et al., 1994) that potentially coded for part of a mammalian homologue (expressed sequence tag (EST) X81594). Using this sequence information, cDNAs that code for homologous human and mouse proteins were isolated (Wechselberger et al., 1999). Meanwhile, a human EST that codes for another relative had been deposited in the databanks (GenBank accession number AA883760). This was later shown to be a fragment of a protein named prokineticin 1/EG‐VEGF (endocrine‐gland vascular epithelial growth factor) (Li et al., 2001; LeCouter et al., 2001).

These findings clearly show that a novel family of small vertebrate proteins exists. As reviewed in this article, several groups are now studying these proteins and their many biological functions.

Nomenclature

There are now many cases in which homologous proteins from different species have diverse names, which is extremely confusing for newcomers and non‐specialists. Indeed, it was recently mentioned in general terms in a Nature commentary that “nomenclature has gone berserk” (Pearson, 2001).

In the protein family described here, we see this happening already. Certainly, the original name, protein A, for the component of the mamba venom is unsatisfactory, as there is the widely used bacterial protein of the same name that binds to immunoglobulins. Schweitz et al. (1990, 1999) subsequently proposed mamba intestinal toxin 1 (MIT1) as a new name. However, whereas the ‘I’ refers to the action of the protein on the guinea pig intestine, it is now misleading to call it a toxin, as mammalian proteins with the same properties are naturally present in various tissues without causing harm. For the frog skin protein, the rather inconspicuous name Bv8 was chosen (from Bombina variegata with a molecular mass of ∼8 kDa). Six cDNAs that code for variants of Bm8, the homologous protein to Bv8 from the skin secretions of the frog Bombina maxima, have recently been deposited in the databanks by two groups (GenBank accession numbers AF411090 and AF411091, and AJ440231–AJ440234). The situation is even more complex for the two mammalian members of the protein A/MIT1/Bv8/Bm8 family. The orthologues isolated by cDNA cloning from mouse brain, and from human and mouse testes, were simply referred to as human/mouse Bv8 (Wechselberger et al., 1999), but more recent results show that this is probably misleading as frog Bv8 is more closely related to the other human variant that has been deposited in the databanks (see below). The two human cDNAs were isolated independently by ZymoGenetics (Seattle, WA, USA), which filed a patent and named the deduced products ‘Zven proteins’ (patent WO 0136465). Zhou and colleagues, who also isolated these human cDNAs, termed the corresponding proteins ‘prokineticin 1’ and ‘prokineticin 2’ (Li et al., 2001), again mainly referring to their action on the guinea pig ileum. However, the name prokineticin applies to the mature proteins, even though it suggests that they are precursors like proinsulin and other pro‐hormones. Finally, through a different route, a group at Genentech (LeCouter et al., 2001) isolated prokineticin 1. On the basis of their assay, they called it EG‐VEGF.

In view of the diverse functions of these mammalian proteins, and particularly because new ones have been recently discovered, a family name that is based on structural characteristics would clearly be desirable. All these proteins have the identical amino‐terminal sequence AVIT, and so we would like to propose the general name ‘AVIT proteins’. Therefore, there would be mamba and frog AVIT proteins, and in mammalian species—depending on the sequence of the signal peptide, the mature protein and the gene structure—there would be at least two subgroups of these proteins. Type 1 would correspond to prokineticin 1/EG‐VEGF (Li et al., 2001; LeCouter et al., 2001), and type 2 to prokineticin 2 and the mammalian Bv8 proteins (see Wechselberger et al., 1999). It should be added that, in PubMed, there are no entries for AVIT, so there would also be no confusion in future searches.

Protein structure

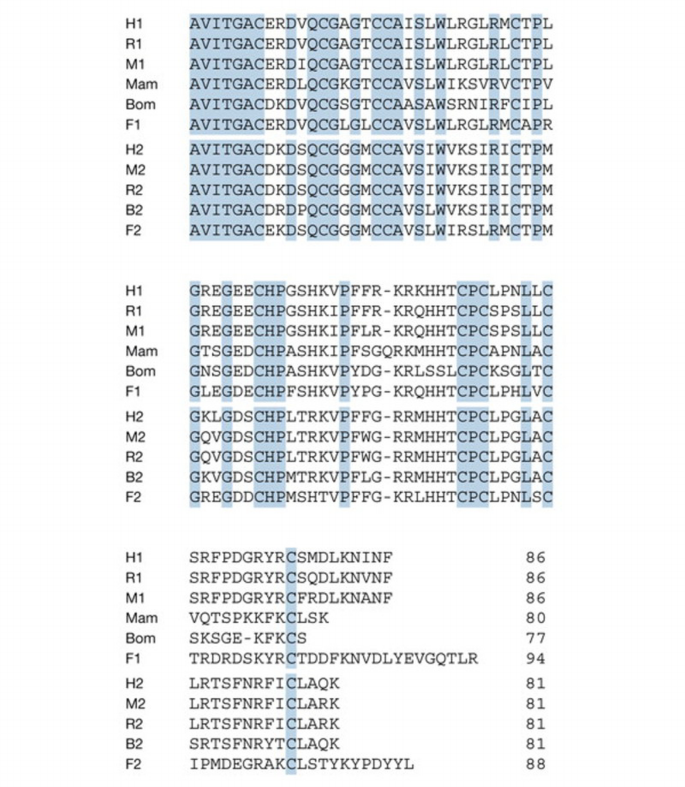

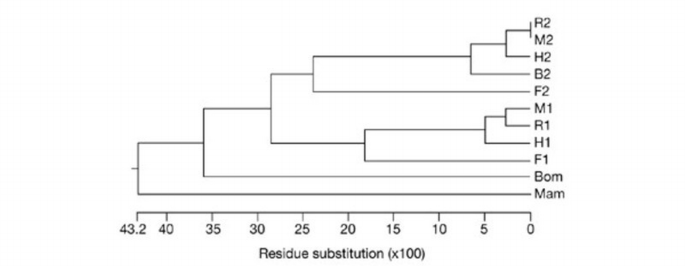

The AVIT family comprises a group of small proteins of about 80–90 amino acids in length. Overall, the identity between the proteins from fish, frog, snake and several mammalian species is high, particularly in the N‐terminal and central regions (Fig. 1). Most of the differences are found close to the carboxyl end, which may thus be less important for biological functions. A phylogenetic tree constructed from the available sequences is shown in Fig. 2. In this comparison, we have included the sequences of the type 2 AVIT protein, determined by cDNA cloning from bull testes (GenBank accession number AY192557), and of the two AVIT proteins of the fugu fish (Takifugu rubripes; H. Tian, personal communication). These data show that AVIT proteins are present in many vertebrate species, ranging from fish to humans.

Figure 1

Amino‐acid sequences of mature AVIT proteins from different species. All mammalian and fish sequences are deduced from cloned complementary DNAs. Numbers refer to type 1 and type 2 proteins. B, bull; Bom, Bombina; F, fugu; H, human; M, mouse; Mam, black mamba; R, rat. The mamba sequence is from Joubert & Strydom (1980) and Schweitz et al. (1999); the Bombina cDNA sequence is from Mollay et al. (1999); human and mouse sequences are from Wechselberger et al. (1999), Li et al. (2001) and LeCouter et al. (2001); rat sequences are from Masuda et al. (2002); the bovine sequence has been deposited in GenBank (M.W. et al., personal communication; accession number AY192558); the fugu sequences have been kindly communicated by H. Tian.

Figure 2

Phylogenetic tree constructed with CLUSTAL W (version 1.82) software using the amino‐acid sequences of the mature proteins. (Abbreviations are as in Fig. 1.)

One notable characteristic of these proteins is the presence of ten cysteines with identical spacing, although this is not unique to this small family. A similar motif is also present in mammalian co‐lipase (Wicker & Puigserver, 1990; Van Tilbeurgh et al., 1992) and in the C‐terminal regions of members of the Dickkopf family of extracellular proteins that regulate Wnt (wingless related)/β‐catenin signalling (Glinka et al., 1998). However, this structural similarity is apparently not reflected at the functional level. For example, the frog protein is inactive in an assay for Dickkopf function (C. Niehrs, personal communication). A distant relative of the AVIT family, with similar cysteine spacing but a different N‐terminal sequence, has also been isolated from the venom of the Australian funnel web spider Hydronyche versata (Szeto et al., 2000).

Using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques, Boisbouvier et al. (1998) were able to show that the pattern of disulphide bridges that had previously been determined for co‐lipase (Van Tilbeurgh et al., 1992) is also present in the protein isolated from the venom of the black mamba. It seems highly likely that this is also true for the other members of the AVIT family. The venom protein has a compact structure that is stabilized by five disulphide bridges, with N‐ and C‐ends present at the surface (see ProteinDB, accession number 1ITM). Several charged residues are buried inside the molecule, whereas some hydrophobic ones, such as Trp24, are exposed to the solvent. Moreover, one side of the roughly ellipsoid protein has a positive net charge, whereas the opposite side is hydrophobic.

Messenger RNA and gene sequences

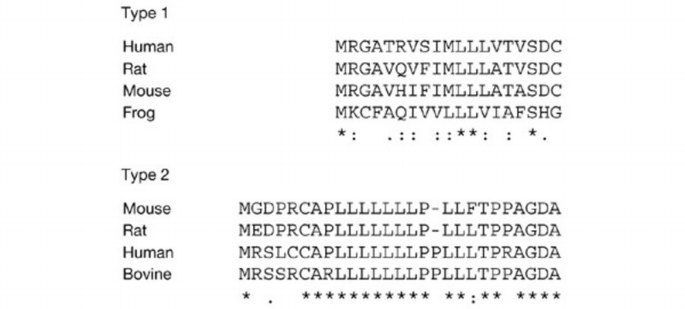

Several cDNAs that code for fish, amphibian and mammalian AVIT proteins have now been cloned. From the sequence of their cDNAs, it can be deduced that these proteins are derived from simple precursors that are comprised of a signal peptide and the mature protein. A comparison of the amino‐acid sequences of the different signal peptides again supports the proposed classification into two subtypes. The signal peptides of the frog pre‐proteins clearly resemble the corresponding type 1 mammalian sequences in their length and amino‐acid similarity. Conversely, the genes for the type 2 precursors of Bv8/prokineticin 2 from mammalian species code for highly homologous, longer signal sequences with no discernible similarity to those of the other group (Fig. 3). The signal peptides of the precursors of the two fugu AVIT proteins are different from those of the other vertebrate proteins (H. Tian, personal communication).

Figure 3

Comparison of signal peptides of type 1 and type 2 AVIT proteins. Signs used are as defined in CLUSTAL W (an asterisk denotes identity in all sequences of the alignment; colons denote conserved substitutions; full stops denote semi‐conserved substitutions).

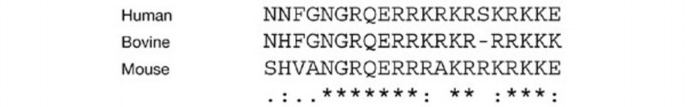

The analysis of the type 2 mRNAs from human, mouse and bull testes revealed the presence of an alternatively spliced form with a similar insert of 20 or 21 amino acids after residue 47 (Wechselberger et al., 1999; GenBank accession numbers AY192557 and AY192558). The inserts (Fig. 4) are rich in arginines and lysines and contain several potential cleavage sites for prohormone convertases. This indicates that two‐chain forms of these type 2 AVIT proteins might exist, but at present nothing is known about the structure and function of the variants. It should be added that the larger form seems to be present only in testes (Wechselberger et al., 1999).

Figure 4

Amino‐acid sequences of the basic insert encoded by exon 3 of mammalian type 2 AVIT genes. (Symbols are as in Fig. 3.)

An analysis of the mouse and human genes has shown that the type 2 precursor is encoded by four exons, of which the third is subject to alternative splicing (Jilek et al., 2000). This gene is located on mouse chromosome 6, close to the gene maternal embryonic message 1 (Mem1), and on human chromosome 3p21.1. The gene that encodes the type 1 precursor is located on human chromosome 1p21 and on mouse chromosome 3. The exon–intron boundaries are conserved between the two genes. However, in the human and mouse genomes, the exon that encodes the highly basic insert that is present in the type 2 AVIT proteins is absent from the type 1 genes.

Tissue distribution

Peptides and proteins that are present in amphibian skin secretions or in snake venom often have homologues in mammals (Lazarus & Attila, 1993; Kochva, 1987). In northern blots, the strongest signals were obtained with RNA from human, mouse and rat testes (Wechselberger et al., 1999; Masuda et al., 2002). In a more detailed analysis using in situ hybridization to mouse and rat brain sections, the Bv8 mRNA was detected in many regions, including the cortex, limbic region, cerebellar Purkinje cells, and dorsal and ventral horns of the spinal cord (Melchiorri et al., 2001). It was also shown recently that the mRNA that codes for prokineticin 2 is rhythmically expressed in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (Cheng et al., 2002). Of the mammalian AVIT proteins, only EG‐VEGF/prokineticin 1 has so far been isolated from cow's milk (Masuda et al., 2002).

Biological functions

The stimulation of the contraction of the guinea pig ileum and, to some extent, of the colon, was first shown for the protein obtained from the venom of the black mamba (Schweitz et al., 1990, 1999), and subsequently for the frog skin protein (Mollay et al., 1999) and recombinant prokineticins 1 and 2 (Li et al., 2001). All the members of this family that have been tested so far bind to receptors on the guinea pig ileum and elicit its contraction.

Further experiments have shown that in rats, intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of a few micrograms of Bv8 made the animals more sensitive to noxious stimuli (Mollay et al., 1999). This hyperalgesia developed within about 30 min and lasted for more than one hour. The snake venom protein was 3–5 times more potent than Bv8 in tail‐flick and paw‐pressure tests, which measure nociceptive (pain) sensitization.

In subsequent investigations, Negri et al. (2002) showed that this hyperalgesic effect is even more pronounced when the frog skin protein was injected subcutaneously (s.c.), into a blood vessel (i.v.) or into the spinal chord (intrathecally). Systemic nociceptive sensitization was observed at doses of 0.06–500 pmol kg−1 s.c. or i.v., and with 6–250 fmol kg−1 intrathecally. This effect is caused by binding of frog Bv8 to receptors in dorsal root ganglia. EG‐VEGF, the mammalian type 1 AVIT protein, also binds to these receptors, albeit with at least ten times less affinity.

Apart from these biological functions—namely stimulation of the guinea pig ileum and nociceptive sensitization—AVIT proteins are also involved in other physiological processes. EG‐VEGF was discovered in a search for secreted human proteins that stimulate the proliferation of capillary endothelial cells derived from bovine adrenal cortex (LeCouter et al., 2001). Unlike VEGF, recombinant EG‐VEGF only acts on endothelial cells from steroid‐producing glands such as the ovary, the Leydig cells of the testis and the adrenal cortex. Both VEGF and EG‐VEGF also stimulate angiogenesis and enhance permeability (fenestration) in these endothelial cells, possibly in a coordinated fashion. EG‐VEGF may, therefore, be an example of a tissue‐specific angiogenic factor (LeCouter et al., 2002).

Moreover, as already mentioned, prokineticin 2 seems to control behavioural circadian rhythms (Cheng et al., 2002). In the suprachiasmatic nucleus of mice, the level of prokineticin 2 mRNA is about 50 times higher at its peak in the light than during darkness. Moreover, i.c.v. injection of recombinant prokineticin 2 was shown to suppress the nocturnal locomotor activity of rats.

AVIT receptors and downstream signalling

Signals from numerous hormones, growth factors, neurotransmitters, and so on, are transduced to the cytoplasm of target cells through G‐protein‐coupled receptors (GPCRs). The binding of recombinant prokineticins to receptors that are present on the guinea pig ileum was partially inhibited by the non‐hydrolysable GTP analogue GTPγS, suggesting that the receptors for these proteins belong to the GPCR family. Indeed, two human orphan GPCRs (D.C.‐H. Lin et al., 2002; Soga et al., 2002), as well as their rat and bovine homologues (Masuda et al., 2002), have recently been characterized and were found to bind AVIT proteins. Prokineticin receptors 1 and 2 are present in several tissues, the latter mainly in the central nervous system. The human receptors are more than 85% identical, and the corresponding genes are located on chromosomes 2 and 20, respectively. Prokineticin 2 has a higher affinity for both receptors than does prokineticin 1.

The signal transduction pathways that are activated by the binding of AVIT proteins to these receptors have been studied in several test systems. It was found that AVIT proteins stimulate the p44/p42 mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (also known as ERK1/ERK2) and phosphoinositide turnover. For example, the addition of frog Bv8 to rat cerebellar granule cells leads to an increase in phosphorylated p44/p42 MAPK, as well as an increase in phosphorylated Akt, a target of phosphatidylinositol‐3‐OH kinase (PI(3)K; Melchiorri et al., 2001). Similar results were obtained for EG‐VEGF/prokineticin 1 in adrenal‐cortex‐derived endothelial cells (R. Lin et al., 2002). This effect on p44/p42 MAPK was also observed for the snake venom protein MIT1, which was in fact more active than the prokineticins (Masuda et al., 2002). All these effects were blocked by PD98059, which is an inhibitor of p44/p42 MAPK.

The binding of AVIT proteins to their receptors also induced a transient, dose‐dependent increase in intracellular Ca2+ (D.C.‐H. Lin et al., 2002; Masuda et al., 2002; Negri et al., 2002). The concentrations for half‐maximal responses were in the range 0.1–10 nM. At the cellular level, AVIT proteins have been found to stimulate proliferation and migration of adrenal‐cortex‐derived endothelial cells (R. Lin et al., 2002; Masuda et al., 2002), and to protect cerebellar granule cells from apoptosis induced by depletion of serum and K+ ions (Melchiorri et al., 2001).

Concluding remarks

The AVIT family comprises two types of protein that are widely distributed in vertebrates. The function of the snake venom and frog skin proteins in their respective secretions is unknown. It seems doubtful that, after being bitten by a black mamba, the hyperalgesia induced by protein A/MIT1 is ever felt before the victim dies.

AVIT proteins bind to two receptors that are present on various mammalian cells, which stimulates the p44/p42 MAPK pathway, as well as Akt phosphorylation by PI(3)K. This may lead to cell division and migration, contraction or protection from apoptosis. In whole animals, s.c., i.v. or intrathecal injection causes hyperalgesia, whereas i.c.v. injection alters nocturnal locomotor activity. It is likely that other biological effects will be found in the future. For example, by far the largest amount of the mRNA that encodes mammalian Bv8/prokineticin 2 is present in the late spermatocytes of mouse testes.

How are these several and distinct functions elicited by just two related proteins? Some of the observed effects may be due to autocrine or paracrine action in the vicinity of the site of secretion. The action of EG‐VEGF in steroid‐producing glands, the secretion of prokineticin 2 by cerebellar granule cells or in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, as well as the contraction of the guinea pig ileum by prokineticins 1 and 2 could be examples of this route. Conversely, frog Bv8 and EG‐VEGF also act following peripheral application, s.c. or i.v., on cells in the spinal cord, which leads to hyperalgesia to noxious stimuli.

As for future experiments, it will be interesting to analyse the phenotypes of mice that lack the genes encoding either of the two AVIT proteins, or one or both of their receptors. From a medical point of view, the possibility that such studies may lead to the characterization of a new pathway for pain perception, that acts through receptors in the spinal cord, could be particularly important.