Connexin32 as a tumor suppressor gene in a metastatic renal cell carcinoma cell line (original) (raw)

Main

Gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) has been considered the only route allowing direct transfer of small metabolites between cells to maintain homeostasis in multicellular organisms (Simpson et al., 1977). The gap junction is made up of juxtaposed transmembrane hemichannels (connexons) provided by adjacent cells, and each connexon of six connexin (Cx) protein subunits (Stauffer et al., 1991). So far, cDNAs from at least 20 different Cx molecules have cloned in humans (Willecke et al., 2002). Different combinations of Cx molecules in different tissues contribute to cell differentiation and cell growth control (Paul, 1995).

Vast lines of evidence strongly support the hypothesis that the Cx gene acts as a tumor suppressor gene (Fittzgerald and Yamasaki, 1990). Tumor-promoting agents and oncogenes disrupt Cx-mediated GJIC, whereas antitumor agents such as retinoids upregulated the GJIC (Trosko et al., 1993). Decreased or diminished expression and function of Cx genes are usually observed in most tumor cells (Yamasaki and Naus, 1996). Furthermore, cells derived from the Cx43 gene knockout mice had a higher tendency for tumorigenesis compared with the wild type (Martyn et al., 1997). More direct evidence for the tumor-suppressive effect of Cx genes has been obtained by transfection of the genes into noncommunicating tumor cells (Rae et al., 1998). In the transfected tumor cells, Cx genes conferred a reduced growth rate in culture as well as in nude mice. Recent studies including our report have suggested that not all Cx genes are able to exert a tumor-suppressive effect on a given tumor, but rather that there seems to be a Cx-cell type compatibility for this effect (Bond et al., 1994; Yano et al., 2001). That is, Cx exerts growth control only in tissues or cell types in which the particular Cx is naturally expressed. At present, this tumor-suppressive effect of this gene has already been established in primary cancers; however, the role of Cx genes in progressive and metastatic cancers is unclear, and seems to be very limited (Nicolson et al., 1988; Holder et al., 1993). In one case, we have reported that Cx26 expressed in liver cancer, which acts as a tumor suppressor gene for liver cancer and is expressed in the progenitor cell of liver cancer, inhibits cellular invasiveness involved in the process of cancer metastasis (Yano and Yamasaki, 2001). From this report, it seems to be possible that Cx gene, which is expressed in the progenitor cell and has a tumor-suppressive effect against the primary cancers, also acts as a tumor suppressor gene in the progressive and metastatic cancers.

In our previous study, we have shown that Cx32 is expressed in the progenitor cell of renal cell carcinoma (RCC), is downregulated in cancerous regions of human kidneys and acts as a tumor suppressor gene in primary RCC (Yano et al., 2003). However hand, human RCC has a very poor prognosis, due in large part to the fact that nearly 30% of all patients exhibit metastatic disease at the time of initial presentation, and of patients with localized disease, 40% ultimately develop distant metastases following removal of the primary tumor (Motzer et al., 1996). In addition, the results of patients with advanced or metastatic RCC are most unsatisfactory (Motzer and Russo, 2000). Thus, to establish a new effective therapy for metastatic RCC is an urgent issue that should be resolved in clinical cancer therapy. If we should determine a new tumor suppressor gene against metastatic RCC, we may establish a new effective therapy for cancer based on the tumor-suppressive effectives of the new suppressor gene. In this context, the present study was undertaken to estimate whether Cx32 could act as a tumor suppressor gene against a metastatic RCC cell line.

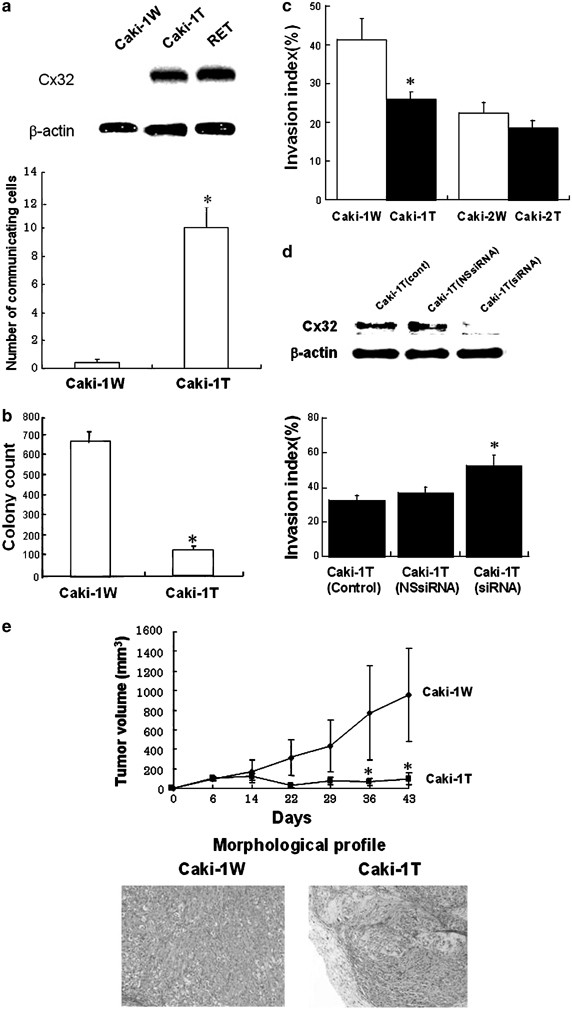

In order to estimate the tumor-suppressive effects of Cx32 against the metastatic RCC cells, we transfected human Cx32 cDNA into a representative human metastatic RCC cell line, Caki-1 cell, which lacks endogenous Cx32, and established the cell expressing Cx32. In this study, we combined all the surviving clones without being cloned and used the combined clones in order to examine the effect of transfection with Cx32 cDNA on the malignant potential of the RCC cells without any influence of clonal variations. Firstly, we checked the expression of Cx32 and the restoration of GJIC capacity in Caki-1 cells. As shown in Figure 1a, the expression of Cx32-transfected Caki-1 (Caki-1T) cells was confirmed, but the expression of Cx32 in mock-transfected Caki-1 (Caki-1W) cells was not observed. In conjunction with the expression, the GJIC capacity in CAKI-1T was much higher (statistical significance) than that in Caki-1W (Figure 1a). These results suggest that the expression of Cx32 relates to the restoration of GJIC in Caki-1 cells. Next, we estimated if Cx32 could reduce tumorigenicity in vitro as well as cellular invasion capacity in vitro. As shown in Figure 1b and c, Cx32 reduced anchorage independency and cellular invasion capacity with statistical significances. Also, in order to confirm the suppressive effect of Cx32 on malignant phenotype related to progression and metastasis in RCC, we compared the effect of Cx32 on cellular invasion capacity between Caki-1 cells from metastatic RCC and Caki-2 cells from primary RCC. As shown In Figure 1c, invasion capacity in Caki-2 cells was lower than that in Caki-1 cells, and Cx32 showed a slight suppression on cellular invasion in Caki-2 cells, different from Caki-1 cells. This result suggests that invasive capacity relates to malignancy of RCC cell lines and that Cx32 favorably reduces the invasive capacity in the more invasive RCC cell line (Caki-1 cell). Since it has been well known that changes of several cellular events are required for primary cancer cells to acquire invasive phenotypes during tumor progression (Mareel et al., 1997), Cx32 may suppress the key event(s) related to cell invasion in RCC cells. In order to further clarify the inhibitory effect of CX32 on the invasive capacity, under the silencing of Cx32 caused by short interfering RNA (siRNA) for the Cx gene, we estimated cellular invasion capacity in Caki-1T. As shown in Figure 1d, the silencing of Cx32 enhanced cellular invasion in Caki-1T. This result supports the observation that Cx32 inhibits invasive capacity in Caki-1 cells.

Figure 1

Cx32 suppresses anchorage independency, and invasive capacity in Caki-1 cells and the development of Caki-1 cells in nude mice. The Caki-1 cell was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA), and the cell was maintained as described previously (Hirai et al., 2003). The human Cx32 cDNA was subcloned into pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen, CA, USA), and Caki-1 cells were transfected with pcDNA3-Cx32 (Caki-1T) as well as empty pcDNA3 vector, as a control (Caki-1W). The cells were selected in culture medium containing G418 (Sigma, MO, USA). Data were analysed, where appropriate, by one-way analysis of variance followed by Student's _t_-test or Duncan's multiple-range test. (a) The expression level of Cx32 in each cell was determined by Western blot analysis as described previously (Hirai et al., 2003). _β_-Actin was used as a control for equal protein loading. RET (human renal epithelial cell) was used as a positive control to detect Cx32 expression. GJIC was estimated by dye (neurobiotin) transfer assay as described previously (Yano et al., 2001). Each column represents mean from 20 determinants, and vertical lines indicate s.e. *P<0.05 vs Caki-1W. (b) Anchorage independency was determined by soft agar assay as described previously (Yano et al., 2001). (c) Invasion assay was performed as described previously, using a Matrigel invasion chamber (Yano and Yamasaki, 2001). In order to compare the effect of Cx32 on invasion capacity between the metastatic RCC cell line (Caki-1) and primary RCC cell line (Caki-2), we also used Caki-2 cells having Cx32 expression (Fujimoto et al., 2004). Caki-2T, Caki-2 cells transfected with pcDNA3-Cx32; Caki-2W, Caki-2 cells transfected with empty pcDNA3 vector. (d) Cx32 gene was downregulated by siRNA for Cx32 (Qiagen, MD, USA) as described previously (Fujimoto et al., 2004). At 48 h after siRNA treatment, the expression level of Cx32 was determined by Western blot analysis. Cx32 siRNA: sense, 5′-AAGAGGCACAAGGTCCACATCdTdT-3′; antisense, 5′-GAUGUGGACCUUGUGCCUCUUdTdT-3′; nonspecific control siRNA: sense, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUdTdT-3′: antisense, 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAAdTdT-3′. Cont, vehicle treatment; NSsiRNA, nonspecific control siRNA treatment; siRNA, siRNA for Cx32 treatment. At 48 h after siRNA treatment, invasion assay was carried out as mentioned in (c). (e) Time-dependent changes of tumor volumes in nude mice. Cells 1 × 107 in each group (_N_=3) were subcutaneously injected into the backs of 5-week-old BALB/c An-nu/nu athymic mice (Japan Clea, Tokyo, Japan). After injection, the growth of tumor nodules was estimated by direct measurement with calipers. Tumor volumes were calculated as π/6 × large diameter × (small diameter)2. At the end of this experiment, tumors were carefully removed after killing, fixed with 20% formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections, 4 _μ_m thick, were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathological examination. Values are expressed as the means from three mice, and each bar indicates s.e. *P<0.05 vs Caki-1W. Histological profiles of tumors in nude mice inoculated with Caki-1W and Caki-1T (Magnification, × 40)

In order to further establish the role of Cx32 gene as a tumor suppressor gene in Caki-1 cells, we next examined whether Cx32 could have an in vivo tumor-suppressive effect against the cells. As shown in Figure 1e, the growth of Caki-1W and Caki-1T cells in mouse xenograft model was different, with a statistical significance. Taken together, it is further confirmed that Cx32 acts as a tumor suppressor gene against Caki-1 cells. Interestingly, there was histological difference between the profile of Caki-1W and Caki-1T cells in mouse xenograft model (Figure 1e). Caki-1W cells formed morphologically poorly differentiated clear cell G3 tumors that did not form grossly or microscopically identifiable structures (Korhonen et al., 1994). However, the tumor from Caki-1T cells was markedly regressed with hyalinization, and the residual tumor cells were small in number. In addition to this morphological change, we also observed the induction of a differentiation marker of progenitor cell for RCC, Cadherin-6, in Caki-1 cells by Cx32 (unpublished data). These results mean that CX32 partly induces differentiation in Caki-1 cells. These observations can further support our conclusion that Cx32 acts as the tumor suppressor gene in RCC cells having malignant phenotypes related to progression and metastasis.

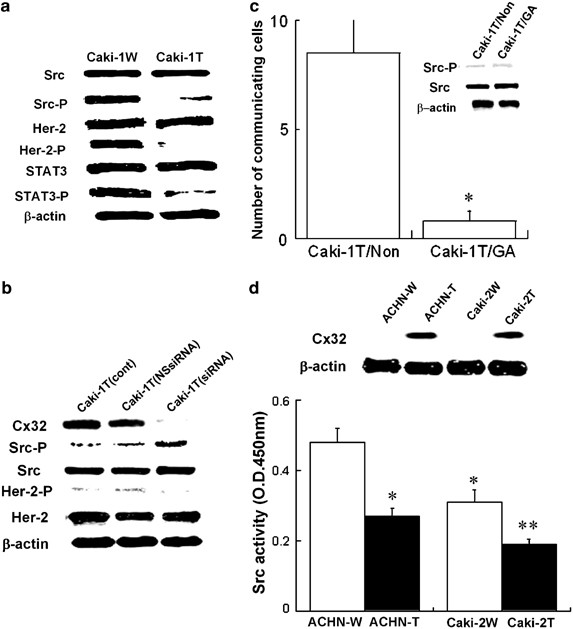

We have recently reported that Cx32 has a negative growth effect on primary tumor cells due to the inactivation of Her-2 (Fujimoto et al., 2004). Furthermore, it has been reported that the interaction of Her-2 with Src contributes to malignant phenotypes in several types of cancers (Ren and Schaefer, 2002). Therefore, we next estimated whether Cx32 could regulate Her-2/Src and their related signal molecules in Caki-1 cells. As shown in Figure 2a, it became clear that Cx32 expression in Caki-1 cells suppressed Her-2 and/or Src-dependent signaling. In order to clarify whether Cx32 inhibited the activation of Her-2 and/or Src molecules, we determined the activated level of each molecule under the silencing of Cx32 gene by siRNA treatment. As a result, the downregulation of Cx32 had different effects on the inactivation of Src and Her-2 (Figure 2b). That is, Cx32 primarily induced the inactivation of Src but not Her-2 in Caki-1 cells. Also, we observed that the inhibition of GJIC function mediated by Cx32 did not affect the activation of Src in Caki-1 cells (Figure 2c). These results suggest that a primary target molecule regulated by Cx32 in Caki-1 cell is Src and that the regulation by Cx32 is irrespective of its GJIC function. This observation is in agreement with a previous report that GJIC-independent function of Cx gene contributes to its potential tumor-suppressive effect (Mesnil, 2002). Next, in order to confirm that the inactivation of Src by Cx32 in Caki-1 cells is also observed in other RCC cells, we selected two human RCC cell lines, ACHN and Caki-2 cells, and estimated the inactivation of Src. As shown in Figure 2d, Cx32 expression suppressed Src activity in both the cell lines with statistical significances. This result suggests that the inhibition of Src activity by Cx32 may have relevance to in vivo growth of the RCC cells.

Figure 2

Cx32 suppresses the activation of Src, and its related cell growth and survival signaling in a GJIC-independent manner. (a) Whole-cell lysates were prepared from Caki-1W and Caki-1T cells in subconfluent status and subjected to Western blot analysis to assess protein expression, using each antibody. Src-P, Her2-P and STAT3-P indicate the activated (phosphorylated) form of each protein. (b) siRNA for Cx32 treatment was carried out for 24 and 48 h as mentioned in Figure 1d. At each point, the level of the Cx32 as well as the activation of Src and Her-2 was estimated by Western blot analysis. (c) The cells were treated with 2.5 μ M 18_α_-glycyrrhetinic acid (a specific inhibitor against GJIC) for 48 h. Control was treated with vehicle only. GJIC was determined as mentioned in Figure 1a. Each column represents mean from 20 determinants, and vertical lines indicate s.e. Caki-1T/Non, vehicle treatment; Caki-1T/GA, GA treatment. *P<0.05 vs Caki-1T/Non. The activation of Src and Her-2 was determined by Western blot analysis as mentioned in (a). (d) ACHN cells, a cell line established from human primary RCC (American Type Culture Collection), were transfected with pcDNA3-Cx32 (ACHN-T) as well as empty pcDNA3 vector, as a control (ACHN-W). The cells were selected in culture medium containing G418 (Sigma, MO, USA). Src activity was determined by Tyrosine Kinase Assay Kit for Colorimetric Detection according to the instruction manual (Upstate biotechnology). The level of Cx32 protein was estimated by Western blot analysis as mentioned in Figure 1a

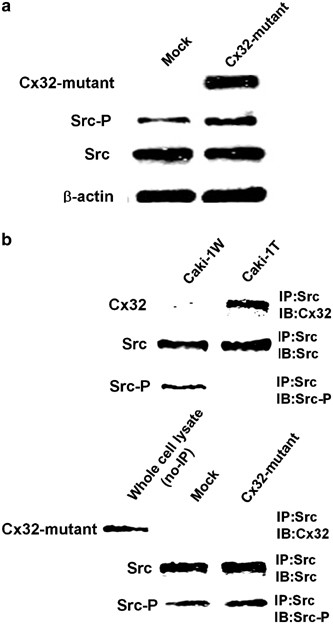

Since it has been known that Cx43 regulates Src kinase through interaction of the Cx C-terminal tail with the kinase irrespective of the GJIC function (Goodenough and Paul, 2003), we speculated that the C-terminal tail of Cx32 could be required for regulation of the Src activation. In this context, we established Caki-1 cells having the expression of Cx32 mutant as lacking C-terminal tail (Omori and Yamasaki, 1999) to estimate the possible mechanism on the suppressive effect of CX32 on the Src activation. As shown in Figure 3a, the Cx32-deleted mutant did not affect the activation of Src in Caki-1 cells. Moreover, immunoprecipitation assays revealed that the C-terminal tail of Cx32 gene was necessary for the interaction of Cx with Src and that the interaction was required for the inactivation of the Src kinase (Figure 3b). Overall, it seems that Cx32 directly and/or indirectly interacts with Src via the C-terminal tail of Cx and regulates the Src activity.

Figure 3

The C-terminal tail of Cx32 is required for regulation of Src activity. (a) Caki-1 cells were transfected with pRc/RSV-deleted mutant of the Cx32 C-terminal tail (Cx32-mutant) as well as empty pRc/RSV vector (Invitrogen), as a control (Mock). In the deleted mutant of Cx32, 69 amino acids of c-terminal tail in the Cx gene were deleted, and the expression vector has been established in our previous study (Omori and Yamasaki, 1999). The cells were selected in culture medium containing G418 (Sigma), and all of the antibiotic-resistant clones were pooled as Cx32 mutant. The activation of Src and Stat3 was estimated by Western blot analysis as mentioned in Figure 2a. In order to detect the expression of the Cx32 mutant gene, Western blot analysis was performed using anti-Cx32 antibody recognizing cytoplasmic loop domain (Sigma). (b) The cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-Src antibody as described previously (Genda et al., 2000). Each level of Cx32, Cx32 mutant, Src, and Src-P in the immunoprecipitates was determined by Western blot analysis as mentioned in Figures 1a, 2a and 3a. Whole-cell lysate (no-IP) prepared from Cx32-mutant cells was used as a positive control to detect the expression of the Cx32 mutant gene

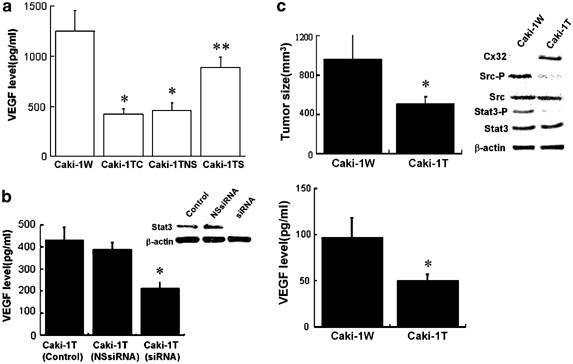

It has been known that all tumors must undergo angiogenesis or neovascularization in order to acquire nutrients for continued growth and metastatic spread (Folkman, 1995). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is the most important factor of inducers of angiogenesis and is upregulated by Src and Stat3 activation (Grunstein et al., 1999; Wiener et al., 1999; Niu et al., 2002). Stat3 is also known as a poor diagnostic factor for RCC (Bromberg and Darnell, 2000); hence, we examined whether Src is located in the upstream of Stat3-dependent signal pathway, using Src dominant-negative mutant. Transfection of the Src mutant gene into Caki-1 cells suppressed the activation of Stat3 as well as Src activity (unpublished data), indicating that Src governed the activation of Stat3 in Caki-1 cells. Next, we investigated whether Cx32 could reduce VEGF generation in Caki-1 cells via Src-Stat3 signaling. As shown in Figure 4a, Cx32 expression in Caki-1 cells reduced the production of VEGF; on the contrary, the downregulation of Cx32 gene by siRNA upregulated the VEGF production in the cells. In order to further clarify the direct effect of Cx32 on VEGF expression via Src-Stat3 signaling in Caki-1 cells, we estimated the effect of siRNA for Stat3 on the production of VEGF under the expression of Cx32 in Caki-1 cells. As a result, the downregulation of Stat3 by siRNA decreased the production of VEGF in Caki-1T (Figure 4b). Overall, it seems that Cx32 suppresses the production of VEGF in Caki-1 cells due to the inactivation of Src-Stat3 signaling. Finally, we examined the relation among the development of tumors, serum human VEGF level and Src signaling in mouse xenograft model to estimate if Cx32 reduces the development of Caki-1 cells in nude mice via Src-Stat3-VEGF signaling. As shown in Figure 4c, there was a close relation among serum human VEGF level, tumor volume, and the activation of Src/Stat3 signaling in nude mice, suggesting that Cx32 suppressed the development of tumors in the mice via the inhibition of Src signaling. In another study, we have shown that a specific Src inhibitor reduced the development of Caki-1 cells in nude mice due to the inhibition of Stat3 activation and VEGF production (submitted data). This report also reinforces our present speculation that Cx32-dependent tumor-suppressive effect on Caki-1 cells in xenograft model partly depends on the inhibition of Src-Stat3-VEGF signal pathway.

Figure 4

Cx32 suppresses Src-Stat3-VEGF signaling in Caki-1 cells. (a) After the cells were cultured for 24 h after siRNA for Cx32 treatment, the medium was changed and a further 48 h culture was performed. After that, the level of VEGF in the medium was determined by a human VEGF ELISA KIT (Biosource International, CA, USA). Caki-1TC, vehicle treatment; Caki-1TNS, nonspecific control siRNA treatment; Caki-1TS, siRNA for Cx32 treatment. *P<0.05 vs Caki-1W; **P<0.05 vs Caki-1TC and Caki-1TNS. (b) After Caki-1T cells were cultured for 24 h after siRNA for Stat3 treatment as mentioned in Figure 1d, the medium was changed and a further 48 h culture was performed. After that, the level of VEGF in the medium was determined by the VEGF ELISA KIT (Biosource International), and the activation of Stat3 was determined by Western blot analysis as mentioned in Figure 2a. The sense and antisense strands of Stat3 siRNA were: sense: 5′-AACAUCUGCCUAGAUCGGCUAdTdT-3′; antisense: 5′-UAGCCGAUGHAGGCAGAUGUUdTdT-3′. The sense and antisense strands of nonspecific control siRNA were: sense: 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUdTdT-3′; antisense: 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGAGAAdTdT-3′. Each column represents the mean from five determinants, and vertical lines indicate s.e. *P<0.05 vs control. (c) The inoculation of the cells was performed as mentioned in Figure 1e. On day 43 after the inoculation, the nude mice (each group _N_=5) was killed, and the tumor size and each protein level were determined. Tumor sizing and each protein level were determined as mentioned in Figures 1a, e and 2a. Each column represents the mean from five determinants, and vertical lines indicate s.e. *P<0.05 vs Caki-1W. The result of Western blot analysis is representative or of five determinants. The level of serum VEGF was determined by the human VEGF ELISA KIT (Biosource International). Each column represents the mean from five determinants, and vertical lines indicate s.e. *P<0.05 vs Caki-1W

The overexpression/activation of Src has been reported in several types of cancers, and the kinase is believed to play critical roles in tumor growth, angiogenesis, invasion, and dissemination (Irby and Yeatman, 2000; Laird et al., 2003). In a previous study, it has been reported that stepwise increase in Src activity during various stages of tumor progression contributes to tumor development and appearance of its malignant phenotypes (Cartwright et al., 1990). In our present study, we observed that Src activity in a poorly differentiated RCC cell line (ACHN) was higher than that in a well-differentiated RCC cell line (Caki-2), indicating that the elevation of Src activity during development of RCC may be related to some malignant phenotypes related to progression and metastasis. Among molecules in the downstream of Src signaling, Stat3 is regarded as one of the most important molecules that induces malignancy of several types of cancers (Buettner et al., 2002). In fact, constitutive activation of Stat3 in human cancers including RCC closely relates to their poor diagnosis (Bowman et al., 2000). Since Stat3 induces the expression of genes that are essential for cell growth, survival, and angiogenesis (Bromberg et al., 1999; Sinibaldi et al., 2000), constitutive activation of the Stat3 confers multiple advantages on tumor cells that are essential for successful malignant progression. In addition, a recent report has suggested that Src also enhances the induction of VEGF via the activation of a main transcription factor that regulates the VEGF promoter (hypoxia-inducible factor 1) other than the activation of Stat3 (Yu and Jove, 2004). Thus, Src/Stat3 signaling is considered as a promising molecular target for powerful intervention in cancer therapy based on the regulation of angiogenesis (Karni et al., 1999; Turkson and Jove, 2000). In this study, we found that Cx32 has potential tumor-suppressive effects against a metastatic RCC cell line (Caki-1 cell) in vivo, due to the suppression of Src-Stat3-VEGF signaling. From the above reports and our present findings, it seems that Cx32 is a promising molecular target to establish a potential new cancer therapy for metastatic RCC through the control of angiogenesis. However, in order to finally establish the usefulness of Cx32 as a new therapeutic target in RCC, we should confirm that there is a close relation among expression level of Cx32, activation of Src/Stat3 signaling, and production of VEGF in invasive and metastatic RCC tissues.

In conclusion, Cx32 gene has a negative growth control of RCC cells having malignant phenotypes related to progression and metastasis, partly through the inactivation of Src-Stat3-VEGF signaling.

References

- Bond SL, Bechberger JF, Khoo NK and Naus CC . (1994). Cell Growth Differ., 5, 179–186.

- Bowman T, Garcia R, Turkson J and Jove R . (2000). Oncogene, 19, 2474–2488.

- Bromberg J and Darnell Jr JE . (2000). Oncogene, 19, 2468–2473.

- Bromberg JF, Wrezeszczynska MH, Devgan G, Zhao Y, Pestell RG, Albanese C and Darnell Jr JE . (1999). Cell, 98, 295–303.

- Buettner R, Mora LB and Jove R . (2002). Clin. Cancer Res., 8, 945–954.

- Cartwright CA, Meisler AI and Eckhart W . (1990). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 558–562.

- Fittzgerald DJ and Yamasaki H . (1990). Tetraog. Carcinog. Mutagen., 10, 89–102.

- Folkman J . (1995). N. Engl. J. Med., 333, 1757–1763.

- Fujimoto E, Satoh H, Ueno K, Nagashima Y, Hagiwara K, Yamasaki H and Yano T . (2004). Mol. Carcinogenesis, 40, 135–142.

- Genda T, Sakamoto M, Ichida T, Asakura H and Hirihashi S . (2000). Lab. Invest., 80, 387–394.

- Goodenough DA and Paul DL . (2003). Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 4, 285–294.

- Grunstein J, Roberts WG, Mathieus-Costello O, Hanahan D and Johnson RS . (1999). Cancer Res., 59, 1592–1598.

- Hirai A, Yano T, Nishikawa K, Suzuki K, Asano R, Satoh H, Hagiwara K and Yamasaki H . (2003). Am. J. Nephrol., 23, 172–177.

- Holder JW, Elmore E and Barrett JC . (1993). Cancer Res., 53, 3475–3485.

- Irby RB and Yeatman TJ . (2000). Oncogene, 19, 5636–5642.

- Karni R, Jove R and Levitzki A . (1999). Oncogene, 18, 4654–4662.

- Korhonen M, Sariola H, Could VE, Kangas L and Virtanen I . (1994). Cancer Res., 54, 4532–4538.

- Laird AD, Li G, Moss KG, Blake RA, Broome MA, Cherrington LM and Mendel DB . (2003). Mol. Cancer Ther., 2, 461–469.

- Mareel MM, Bracke ME, Van Roy F and de Baetselier P . (1997). Encyl. Cancer, 2, 1072–1083.

- Martyn KD, Kurata WE, Warn-Cramer BJ, Burt JM, Tenbroek E and Lau AF . (1997). Cell Growth Differ., 8, 1015–1027.

- Mesnil M . (2002). Biol. Cell, 94, 493–500.

- Motzer RJ, Bander NH and Nanus DM . (1996). N. Engl. J. Med., 335, 865.

- Motzer RJ and Russo P . (2000). J. Urol., 163, 408–417.

- Nicolson GL, Dulski KM and Trosko JE . (1988). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 473–476.

- Niu G, Wright KL, Huang M, Song L, Haura E, Turkson J, Zhang S, Wang T, Sinibaldi D, Coppola D, Heller R, Ellis LM, Karras J, Bromberg J, Pardoll D, Jove R and Yu H . (2002). Oncogene, 21, 2000–2008.

- Omori Y and Yamasaki H . (1999). Carcinogenesis, 20, 1913–1918.

- Paul DL . (1995). Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 7, 665–672.

- Rae RS, Mehta PP, Chang CC, Trsoko JE and Ruch RJ . (1998). Mol. Carcinogenesis, 22, 120–127.

- Ren Z and Schaefer TS . (2002). J. Biol. Chem., 277, 38386–38493.

- Simpson JC, Rose B and Lowenstein WR . (1977). Science, 195, 294–296.

- Sinibaldi D, Wharton W, Turkson J, Bowman T, Pledger WJ and Jove R . (2000). Oncogene, 19, 5419–5427.

- Stauffer KA, Kumar NM, Gilula NB and Unwin N . (1991). J. Cell Biol., 115, 141–150.

- Trosko JE, Madhukar BV and Chang CC . (1993). Life Sci., 53, 1–19.

- Turkson J and Jove R . (2000). Oncogene, 19, 6613–6626.

- Wiener JR, Nakano K, Kruzelock RP, Bucana CD, Bast Jr RC and Gallick GE . (1999). Clin. Cancer Res., 5, 2164–2170.

- Willecke K, Eiberger J, Degen J, Eckardt D, Romualdi A, Guldenagel M, Deutsch U and Sohl G . (2002). Biol. Chem., 383, 725–737.

- Yamasaki H and Naus CCG . (1996). Carcinogenesis, 17, 1199–1213.

- Yano T, Blazquez FJH, Omori Y and Yamasaki H . (2001). Carcinogenesis, 22, 1593–1600.

- Yano T, Ito F, Satoh H, Hagiwara K, Nakazawa H, Toma H and Yamasaki H . (2003). Kidney Int., 63, 381.

- Yano T and Yamasaki H . (2001). Mol. Carcinogenesis, 31, 101–109.

- Yu H and Jove R . (2004). Nature Rev. Cancer, 4, 97–105.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Miss Haruna Satoh for her technical assistance. This work was supported by a grant on Health Sciences Focusing on Drug Innovation from the Japan Health Sciences Foundation (SH24209 and KH 21012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Food Science Research for Health, National Institute of Health and Nutrition, 1-23-1 Toyama, Shinjuku, 162-8636, Tokyo, Japan

Eriko Fujimoto, Hiromi Sato, Sumiko Shirai, Keiko Fukumoto, Hiromi Hagiwara, Kiyokazu Hagiwara & Tomohiro Yano - Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chiba University, 1-8-1 Inohana, Chuo, 260-8675, Chiba, Japan

Eriko Fujimoto, Hiromi Sato, Etsuko Negishi & Koichi Ueno - Department of Pathology, Yokohama City University Medical School, 3-8 Fukuura, Kanazawa, 236-0004, Kanagawa, Japan

Yoji Nagashima - Japan Human Sciences Foundation, 13-4 Nihonbashi-Kodenmacho, Chuo, 103-0001, Tokyo, Japan

Hiromi Hagiwara - Department of Pathology, Akita University School of Medicine, 1-1-1 Hondo, Akita, 010-8543, Japan

Yasufumi Omori - Faculty of Science and Technology, Kwansei Gakuin University, 2-1 Gakuen, Sanda, 669-1337, yogo, Japan

Hiroshi Yamasaki

Authors

- Eriko Fujimoto

- Hiromi Sato

- Sumiko Shirai

- Yoji Nagashima

- Keiko Fukumoto

- Hiromi Hagiwara

- Etsuko Negishi

- Koichi Ueno

- Yasufumi Omori

- Hiroshi Yamasaki

- Kiyokazu Hagiwara

- Tomohiro Yano

Corresponding author

Correspondence toTomohiro Yano.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fujimoto, E., Sato, H., Shirai, S. et al. Connexin32 as a tumor suppressor gene in a metastatic renal cell carcinoma cell line.Oncogene 24, 3684–3690 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1208430

- Received: 21 April 2004

- Revised: 03 December 2004

- Accepted: 06 December 2004

- Published: 14 March 2005

- Issue date: 19 May 2005

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1208430