How hosts control worms (original) (raw)

- Scientific Correspondence

- Published: 04 September 1997

- K. Bairden1,

- J. L. Duncan1,

- P. H. Holmes1,

- Q. A. McKellar1,

- M. Park1,

- S. Strain1,

- M. Murray1,

- S. C. Bishop2 &

- …

- G. Gettinby3

Nature volume 389, page 27 (1997)Cite this article

- 1349 Accesses

- 142 Citations

- 3 Altmetric

- Metrics details

Nematodes are a major cause of disease and death in humans, domestic animals and wildlife. Understanding why some individuals suffer severely whereas others exposed to the same infection remain healthy may assist in the development of rational and sustainable strategies to control infection. Here, using a quantitative genetic analysis of the parasitic nematode population that had accumulated naturally in lambs, we find no apparent influence of host genetics on nematode numbers but an extremely strong influence on average worm length and fecundity. Our results indicate that in growing lambs the main manifestation of genetic resistance is the control of worm fecundity.

The lambs were all straight-bred Scottish blackface sheep from a commercial farm in southwest Strathclyde. We took faecal samples from the rectum of each lamb in late May when the lambs were 3-5 weeks old and then at four-week intervals. After taking each sample, animals were treated with a broad-spectrum anthelmintic (albendazole sulphoxide; Rycoben, Youngs Animal Health, Leyland, UK), given at the recommended dose rate of 5 mg per kg body mass. We assessed the worm load after death at 6.5 months; the number of lambs studied was 501 between 1992 and 1995. We used standard parasitological methods to estimate egg counts and worm burdens1. Larval culture and post-mortem analyses indicated that more than 80% of the parasites present were Ostertagia circumcincta. At least 25 randomly chosen female O. circumcincta were measured for each sheep by image analysis (Foster-Findlay Associates Ltd).

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Additional access options:

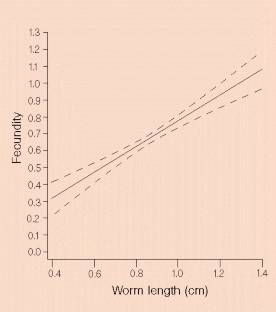

Figure 1: Relationship between worm fecundity and mean worm length.

References

- Armour, J., Jarrett, W. F. H. & Jennings, F. W. Am. J. Vet. Res. 27, 1267–1278(1966).

Google Scholar - Meyer, K. Genet. Selec. Evol. 21, 317–330(1989).

Google Scholar - Bishop, S. C., Bairden, K., McKellar, Q. A., Park, M. & Stear, M. J. Anim. Sci. 63, 423–428(1996).

Google Scholar - Stear, M. J. et al. Parasite Immunol. 17, 643–652(1995).

Google Scholar - McCririe, L. et al. Parasite Immunol. 19, 235–242(1997).

Google Scholar - Stear, M. J., Park, M. & Bishop, S. C. Parasitol. Today 12, 438–441(1996).

Google Scholar

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Glasgow University Veterinary School, Bearsden Road, Bearsden, G61 1QH, Glasgow, UK

M. J. Stear, K. Bairden, J. L. Duncan, P. H. Holmes, Q. A. McKellar, M. Park, S. Strain & M. Murray - Division of Biometrical Genetics, Roslin Institute, Roslin, EH25 9PS, Midlothian, UK

S. C. Bishop - Department of Statistics and Modelling Science, University of Strathclyde, Livingston Tower, 26 Richmond Street, Glasgow, G1 1XH, UK

G. Gettinby

Authors

- M. J. Stear

- K. Bairden

- J. L. Duncan

- P. H. Holmes

- Q. A. McKellar

- M. Park

- S. Strain

- M. Murray

- S. C. Bishop

- G. Gettinby

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stear, M., Bairden, K., Duncan, J. et al. How hosts control worms.Nature 389, 27 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1038/37895

- Issue date: 04 September 1997

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/37895