FTO expression is regulated by availability of essential amino acids (original) (raw)

Introduction

In 2007, single nucleotide polymorphisms in the first intron of fat mass and obesity-related transcript (FTO) were found to be powerfully associated with body mass index, and predisposing to childhood and adult obesity.1 As reported by Frayling et al.,1 those homozygous for the AA ‘risk-allele’ were on average 3 kg heavier than those homozygous for the TT ‘non-risk’ allele. It is important to note that as yet, no conclusive link has been made between the risk alleles and expression or function of FTO. Soon after, we and others showed by bioinformatics analysis that FTO shares sequence motifs with Fe(II)- and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenases.2 In vitro, recombinant FTO is able to catalyze the Fe(II)- and 2- oxoglutarate-dependent demethylation of 3-methylthymine in single-stranded DNA, as well as 3-methyluracil2, 3 and 6-methyl adenosine4 in single-stranded RNA, with concomitant production of succinate, formaldehyde and carbon dioxide, suggesting a potential role for FTO in nucleic acid repair or modification.

FTO deficiency results in a complex phenotype and significant postnatal mortality.5, 6 Mice homozygous for a targeted FTO deletion display postnatal growth retardation, as well as increased food intake and body weight when normalized to lean body mass. In addition, there is a 50% postnatal mortality preweaning.5 Humans homozygous for a loss-of-function mutation in FTO are characterized by a complex phenotype including structural and functional brain malformations and cardiac defects, as well as early mortality before 30 months of age.6 FTO is ubiquitously expressed with highest expression within the brain, including the hypothalamus.2 We have shown that expression of Fto, specifically in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) of the hypothalamus, is bidirectionally regulated as a function of nutritional status; decreasing following a 48-h fast and increasing after 10-week exposure to a high-fat diet, and that modulating FTO levels specifically in the ARC can influence food intake.2, 7

The physiological role of FTO with regard to body weight and energy balance remains elusive. As our previous work has suggested that FTO is nutritionally regulated in vivo, we set out to dissect which individual nutrients could regulate FTO expression on a cellular level. Using mouse and human cell lines, we find that FTO levels are not influenced by serum starvation. We demonstrate, however, that both glucose and essential amino-acid deprivation regulates FTO expression. Amino-acid (AA) deprivation in particular dramatically and reversibly downregulates FTO mRNA and protein levels in mouse and human cell lines.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and experimental treatments

Mouse hypothalamic cells (N46), human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293) and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media (DMEM5796; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), penicillin (100 U ml−1) and streptomycin (100 μg ml−1; Sigma). Cells were grown in humidified atmosphere (5% CO2) at 37 °C. To ensure that no nutrient starvation occurred before the initiation of the treatments, cells were plated in complete media 24 h before the start of the experiments and were grown to ∼60–70% confluency. On the next day, cells were rinsed twice with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline and the media was replaced with experimental media accordingly. The composition of the various media is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Cells were harvested at indicated time points for total RNA and protein extractions.

Real-time PCR and western blots

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini-kit (Qiagen) and was treated with DNase-1 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed on a TaqMan ABI Prism 7900 Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Expression results were analyzed relative to GAPDH and β-actin mRNA content in the same sample. Western blots were performed following the standard procedure using the monoclonal antibodies to mouse FTO (1:1000, PhosphoSolutions, Aurora, CO, USA). β-Actin was used as the loading control (1:2000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. in three independent experiments. Significant differences between –AA and untreated groups were analyzed using the two-tailed Student's _t_-test. _P_-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

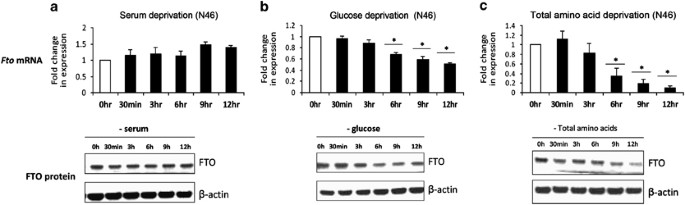

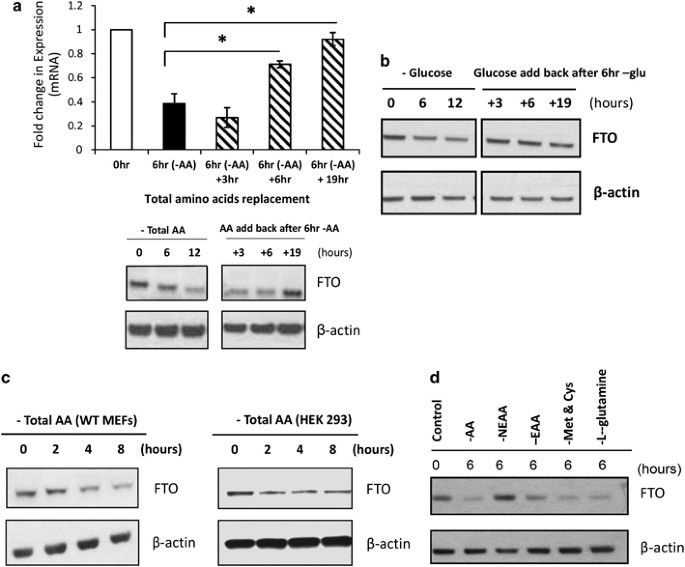

To determine if nutrient availability can influence FTO expression on a cellular level, we subjected murine hypothalamic N46 cells to serum, glucose and AA deprivation over six different time points. We demonstrate that FTO mRNA and protein levels are not affected by up to 12 h of serum starvation (Figure 1a). Glucose and serum deprivation do downregulate FTO expression from 6 h onward, resulting in a 50% drop in FTO mRNA expression at 12 h (Figure 1b). AA deprivation, however, resulted in a very dramatic decrease in FTO expression. FTO transcript levels fall by ∼60% after 6 h of total AA deprivation, ending up at 10% of levels found in untreated cells at 12 h. There is a lag before FTO protein levels begin to drop after 9 h of AA deprivation (Figure 1c). We looked at the expression of multiple housekeeping genes including β-actin, GAPDH, microglobulin (B2M) and 18S in our in vitro experiments. No transcriptional changes in these genes were observed during the 12-h time course of AA deprivation (data not shown). Furthermore, we show that the drop in FTO expression is reversible. FTO mRNA levels drop by 50% after 6 h of AA deprivation, and adding back AA for 6 h partially rescues, whereas 19 h of AA replacement fully rescues FTO expression to untreated levels (Figure 2a). The same can be seen for glucose deprivation (Figure 2b).

Figure 1

Regulation of FTO expression by serum, glucose and AA availability. FTO mRNA and protein expression levels in mouse hypothalamic N46 cells deprived of (a) serum, (b) glucose and (c) total AAs for 0 h, 30 min, 3, 6, 9 and 12 h. Data are normalized to GAPDH and expressed in terms of fold-induction of Fto transcript levels compared with control untreated cells. Error bars represent mean±s.e.m of three independent experiments. _P_-value was calculated using a two-tailed distribution unpaired Student's _t_-test. *P<0.05 compared with untreated cells. FTO protein levels were measured by western blot probed with mouse monoclonal antibodies against FTO. β-Actin was used as a loading control and bands were visualized using Chemiluminescence.

Figure 2

Regulation of FTO by AA deprivation is reversible and is restricted to essential AAs. (a) Change of Fto mRNA and protein expression upon AA deprivation is reversible with AA replacement in N46 cells. Cells were deprived of total amino acid for 6 h, media was then replaced with full media for 3, 6 and 19 h; RNA and protein were collected accordingly. In qRT-PCR, data is normalized to GAPDH and expressed in terms of fold-induction of Fto transcript levels compared with control untreated cells. *P<0.05 compared with 6 h of AA deprivation. Error bars represent mean±s.e.m of three independent experiments. For the western blot, FTO was probed with mouse monoclonal antibodies and β-actin was used as a loading control. (b) Change of Fto mRNA expression with glucose deprivation is reversible with glucose replacement. Cells were deprived with glucose and serum for 6 h, then glucose was added back in and cells were harvested for western blot analysis after 3, 6 and 19 h. (c) Western blot data showing FTO protein expression in human HEK293 cells and MEFs deprived of total amino acids. (d) FTO protein expression in N46 cells deprived of total AAs (AA), non-essential AAs (NEAA), essential AAs (EAA), specific AAs: methionine and cysteine (Met and Cys) and L-glutamine for 6 h. Control represents untreated cells. Western blots were probed with mouse monoclonal antibodies against FTO. β-Actin was used as a loading control and bands were visualized using Chemiluminescence.

To determine whether this phenomenon was peculiar to this cell line, we repeated the experiment in MEFs and human HEK293 cells, and demonstrate a similar downregulation of FTO expression resulting from a lack of total AA (Figure 2c), indicating that this regulation of FTO expression is not cell or species specific.

We next asked if FTO responds to any type of AA in particular. To address this question, we deprived N46 cells of total AAs, essential AAs as well as non-essential AAs, glutamine, and cysteine and methionine, for 6 h, and compared the effects on FTO expression with untreated normal growing cells. As shown above, total AA deprivation for 6 h does indeed downregulate FTO protein expression (Figure 2d). What is clear, however, is that deprivation of essential AAs and not non-essential AAs reduces FTO expression. Deprivation of the specific AAs glutamine or cysteine and methionine appear to elicit a greater drop in FTO expression than that from total AA deprivation.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that FTO expression is influenced by essential AA and, to a lesser degree, glucose availability. However, FTO abundance and how this might link to the regulation of body weight has yet to be determined. Certainly, the weight of evidence from a multitude of animal models, where FTO expression has been perturbed, indicates some role for FTO in energy homeostasis.5, 7, 8, 9, 10

On a whole organism level, animals fed with diets lacking essential AAs are able to recognize the deficiency and within 20 min refuse to eat the imbalanced diet.11, 12, 13 The sensing of AA deficiency is believed to occur at the anterior piriform cortex, but the neuronal route linking the ‘sensor’ to the ‘regulator’ of food intake has yet to be identified.11 At a cellular level, several molecular pathways have been characterized for sensing AA availability. The GCN2 pathway activates downstream phosphorylation of the eukaryotic translation-initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2α), attenuating protein synthesis, rapidly triggering the transcription factor ATF4 and turning on the integrated stress response.14, 15, 16, 17 On the other hand, the mammalian target of rapamycin also senses cellular nutrient and energy levels, including the presence of branched-chain AAs such as leucine.18 The change of FTO expression in response to AA availability might involve either or both of these pathways, and further work is needed to answer these questions.

We measured the half-life of FTO transcript to be around 12 h, thus FTO mRNA expression falls faster than its natural degradation rate, indicating that its regulation by AA or glucose deficiency is likely to be at the transcriptional level, possibly by active degradation. Strikingly, we show that the regulation of FTO occurs only in response to essential AAs. Additionally, we show that deprivation of a more restricted repertoire of essential AAs actually results in a greater drop in FTO expression compared to that from total AA deprivation. It is possible that more than one signaling pathway is involved in the regulation of FTO, and certain AAs, like glutamine, cysteine and methionine, preferentially trigger one pathway over another.19, 20

What our studies do not address is whether FTO has a role in the actual AA-sensing mechanism. It is possibly unlikely that FTO is the ‘sensor’ in itself because of the late response and dramatically dynamic nature of its expression upon nutrient limitation. However, a role for FTO in the sensing of cellular nutritional availability would be congruent with its association with obesity, as well as its regulation by dietary challenges in the whole organism.

In summary, we have shown that FTO expression is regulated by glucose and essential AA availability, and we hypothesize FTO might be involved in the cellular nutrient sensing. Further work is ongoing to determine the mechanism underlying this phenomenon.

References

- Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, Zeggini E, Freathy RM, Lindgren CM et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science 2007; 316: 889–894.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Gerken T, Girard CA, Tung YC, Webby CJ, Saudek V, Hewitson KS et al. The obesity-associated FTO gene encodes a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent nucleic acid demethylase. Science 2007; 318: 1469–1472.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jia G, Yang CG, Yang S, Jian X, Yi C, Zhou Z et al. Oxidative demethylation of 3-methylthymine and 3-methyluracil in single-stranded DNA and RNA by mouse and human FTO. FEBS Lett 2008; 582: 3313–3319.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, Dai Q, Zheng G, Yang Y et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol 2011; 7: 885–887.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Fischer J, Koch L, Emmerling C, Vierkotten J, Peters T, Bruning JC et al. Inactivation of the Fto gene protects from obesity. Nature 2009; 458: 894–898.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Boissel S, Reish O, Proulx K, Kawagoe-Takaki H, Sedgwick B, Yeo GS et al. Loss-of-function mutation in the dioxygenase-encoding FTO gene causes severe growth retardation and multiple malformations. Am J Hum Genet 2009; 85: 106–111.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Tung YC, Ayuso E, Shan X, Bosch F, O'Rahilly S, Coll AP et al. Hypothalamic-specific manipulation of Fto, the ortholog of the human obesity gene FTO, affects food intake in rats. PLoS One 2010; 5: e8771.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Church C, Lee S, Bagg EA, McTaggart JS, Deacon R, Gerken T et al. A mouse model for the metabolic effects of the human fat mass and obesity associated FTO gene. PLoS Genet 2009; 5: e1000599.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Church C, Moir L, McMurray F, Girard C, Banks GT, Teboul L et al. Overexpression of Fto leads to increased food intake and results in obesity. Nat Genet 2010; 42: 1086–1092.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Gao X, Shin YH, Li M, Wang F, Tong Q, Zhang P . The fat mass and obesity associated gene FTO functions in the brain to regulate postnatal growth in mice. PLoS One 2010; 5: e14005.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Gietzen DW . Neural mechanisms in the responses to amino acid deficiency. J Nutr 1993; 123: 610–625.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Harper AE, Benevenga NJ, Wohlhueter RM . Effects of ingestion of disproportionate amounts of amino acids. Physiol Rev 1970; 50: 428–558.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Koehnle TJ, Russell MC, Gietzen DW . Rats rapidly reject diets deficient in essential amino acids. J Nutr 2003; 133: 2331–2335.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Harding HP, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Novoa I, Lu PD, Calfon M et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell 2003; 11: 619–633.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kilberg MS, Pan YX, Chen H, Leung-Pineda V . Nutritional control of gene expression: how mammalian cells respond to amino acid limitation. Annu Rev Nutr 2005; 25: 59–85.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kilberg MS, Shan J, Su N . ATF4-dependent transcription mediates signaling of amino acid limitation. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2009; 20: 436–443.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhang P, McGrath BC, Reinert J, Olsen DS, Lei L, Gill S et al. The GCN2 eIF2alpha kinase is required for adaptation to amino acid deprivation in mice. Mol Cell Biol 2002; 22: 6681–6688.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kimball SR, Jefferson LS . Molecular mechanisms through which amino acids mediate signaling through the mammalian target of rapamycin. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2004; 7: 39–44.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Palii SS, Kays CE, Deval C, Bruhat A, Fafournoux P, Kilberg MS . Specificity of amino acid regulated gene expression: analysis of genes subjected to either complete or single amino acid deprivation. Amino Acids 2009; 37: 79–88.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lee JI, Dominy JE, Sikalidis AK, Hirschberger LL, Wang W, Stipanuk MH . HepG2/C3A cells respond to cysteine deprivation by induction of the amino acid deprivation/integrated stress response pathway. Physiol Genomics 2008; 33: 218–229.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the UK Medical Research Council Center for Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders (MRC-CORD), the EU FP7-HEALTH-2009-241592 EurOCHIP and EU FP7-HEALTH-266408 (Full4Health).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- University of Cambridge Metabolic Research Laboratories, Institute of Metabolic Science, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, UK

M K Cheung, P Gulati, S O'Rahilly & G S H Yeo - NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, UK

M K Cheung, P Gulati, S O'Rahilly & G S H Yeo

Authors

- M K Cheung

- P Gulati

- S O'Rahilly

- G S H Yeo

Corresponding author

Correspondence toG S H Yeo.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on International Journal of Obesity website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheung, M., Gulati, P., O'Rahilly, S. et al. FTO expression is regulated by availability of essential amino acids.Int J Obes 37, 744–747 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2012.77

- Received: 18 January 2012

- Revised: 02 April 2012

- Accepted: 10 April 2012

- Published: 22 May 2012

- Issue date: May 2013

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2012.77