HIV-1 superinfection despite broad CD8+ T-cell responses containing replication of the primary virus (original) (raw)

Increasing evidence suggests that virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses are important in the control of HIV-1 or SIV replication4,5,6,7,8, and inducing and maintaining these responses are considered to be central for the development of effective HIV-1 vaccines. In the simian-HIV (SHIV) model, induction of strong SHIV-specific CD8+ T-cell responses does not prevent infection after challenge but is associated with persistent control of low levels of viral replication and attenuated disease9,10,11. Although similar vaccine regimens have failed to control more pathogenic and less easily neutralizable SIV strains12,13,14, these studies nevertheless provide optimism that an effective vaccine to prevent HIV-1 disease progression in humans could be developed. Indeed, the augmentation of HIV-1-specific immunity by the early treatment of persons with acute HIV-1 infection, followed by supervised treatment interruptions (STI), has been shown1,2,3. Most individuals treated by this method have been able to control, at least transiently, viraemia after the cessation of treatment at levels that did not require the re-initiation of treatment3. One such individual effectively controlled infection for over 290 d after STI but then experienced a marked increase in plasma viral load (Fig. 1a), offering us the opportunity to investigate the immunological and virological correlates of loss of immune control.

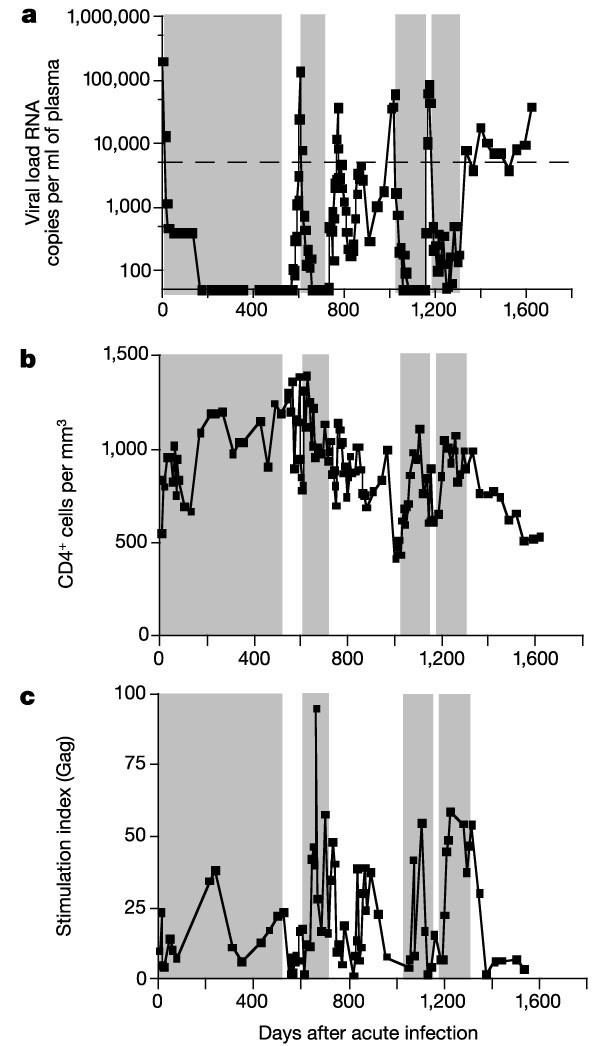

Figure 1: HIV-1 viral loads, CD4+ T-cell counts and Gag-specific lymphoproliferative responses in study subject AC-06.

a, HIV-1 plasma viral loads, b, CD4+ T-cell counts; c, Gag-specific lymphoproliferative responses. Time zero represents the first presentation of AC-06 with symptomatic acute HIV-1 infection. At this time, HIV-1 viral loads were 8.8 × 106 RNA copies per ml of plasma (not shown). Shaded areas represent treatment with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Dotted line indicates 5,000 copies of HIV-1 RNA per ml of plasma.

Subject AC-06 underwent STI 546 d after early treatment of acute HIV-1 infection by a previously reported protocol3. The virus rebounded, and within 60 d (day 606 of infection) exceeded 50,000 HIV-1 RNA copies per ml of plasma, necessitating the re-initiation of therapy (Fig. 1a). Therapy was again interrupted at day 715. Although there was a transient peak in viraemia at day 773, viraemia declined spontaneously and his CD4+ T-cell counts remained stable. He then did not meet the criteria for re-initiating therapy until day 1,020 (305 d after stopping therapy), showing prolonged control of viraemia while off therapy.

At this stage, however, he experienced a sudden rapid increase in viraemia along with a marked drop in CD4+ T-cell counts from 998 cells per µl (day 972) to 515 cells per µl before HAART was reinitiated (Fig. 1b). Subsequent STI 4 months later (day 1,149) was associated with an even more rapid loss of control, in which viraemia exceeded 50,000 RNA copies per ml of plasma within 20 d. After another 4 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), treatment was again stopped (day 1,312) and HIV-1-viraemia once more rebounded but to lower peak concentrations. Although viraemia never exceeded 50,000 RNA copies per ml of plasma, secondary criteria to restart therapy were met at day 86 owing to viral loads above 5,000 RNA copies per ml for three consecutive weeks. At this stage, subject AC-06 chose to decline further drug therapy, with viral loads ranging from 3,700 to 18,200 RNA copies per ml for 280 d, before increasing to 38,000 RNA copies per ml on day 1,622. During this time, his CD4+ T-cell counts declined progressively.

We carried out comprehensive evaluation of the virus-specific immune responses to define the correlates of this loss of immune control. Gag-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferative responses were detected after early treatment3,15,16 and were present during the period of control during the second STI, but they declined with the sudden increase in viraemia (Fig. 1c). Although impairment of HIV-1-specific T-helper cell (TH) responses by continuing low-level viral replication17 before the rebound of viraemia cannot be excluded by these data, they suggest that a sudden loss of Gag-specific TH responses did not precede the observed loss of viral control in this individual. Similarly, only weak neutralizing antibody responses (titres ranging from <4 to 8 reciprocal plasma dilutions) against autologous virus were present during the second STI at the time of viral control.

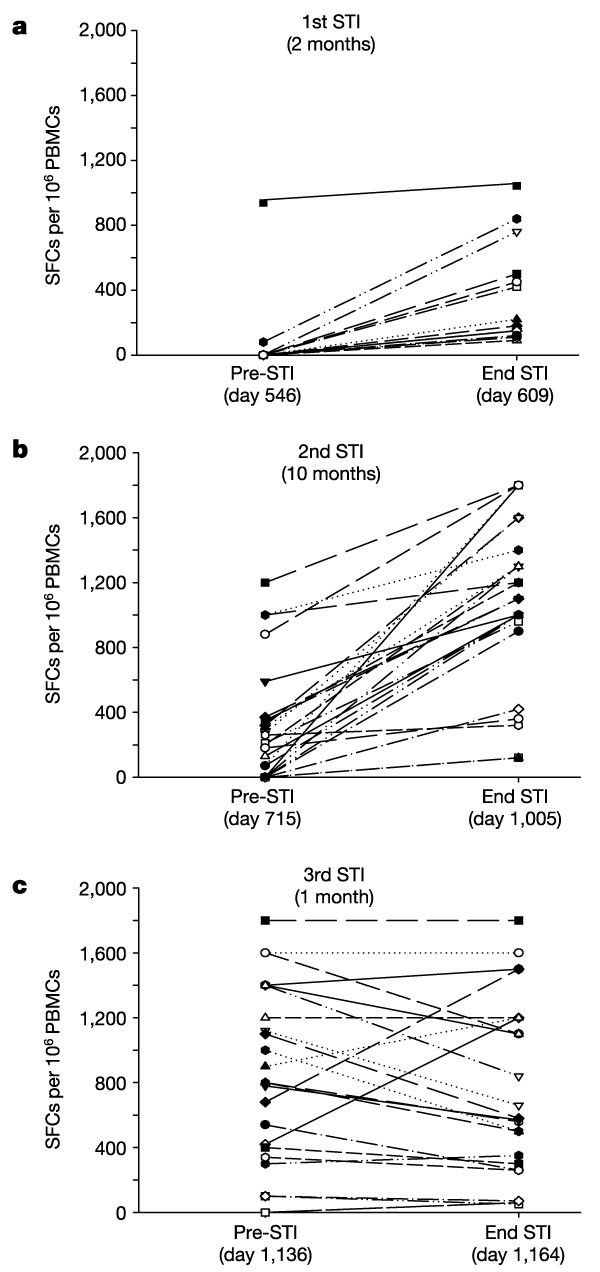

Because animal model data suggest that CD8+ T-cell responses are essential for immune control in AIDS virus infections5,7,18, we measured longitudinally the maintenance of virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses using an interferon-γ (IFN-γ) Elispot assay and 504 clade-B overlapping peptides spanning all expressed HIV-1 proteins. HIV-1-specific CD8+ T-cell responses were enhanced and broadened with re-exposure to antigen during the first and second STIs (see also ref. 19), ultimately targeting 25 distinct cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes with a total of 27,470 spot-forming cells (SFCs) per 106 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) at the end of the second STI (Fig. 2a, b). In addition to IFN-γ secretion after antigenic stimulation, these epitope-specific CD8+ T cells also demonstrated epitope-specific cytotoxic activity (data not shown). But this pattern of enhancement of epitope-specific responses present during the first two STIs changed markedly during the third STI. Although a subset of epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell responses was maintained or expanded further, for the first time some established responses declined (Fig. 2c), leaving a reduced magnitude of 18,250 SFCs per 106 PBMCs (P = 0.01, versus the second STI).

Figure 2: CD8+ T-cell responses to described optimal clade-B sequence cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes during successive supervised treatment interruptions (STIs).

Responses to individual epitopes are shown before and at the end of each STI (a, 1st STI; b, 2nd STI; c, 3rd STI) and are presented as spot-forming cells (SFCs) per million peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). The duration of STI is indicated in months. All epitope-specific responses increased until the third STI, during which more than half of the responses declined.

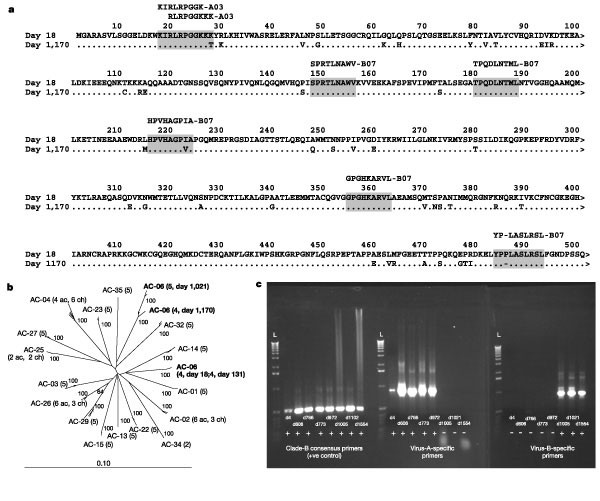

To investigate the relationship between sequence variation within targeted epitopes and loss of immune control18, we sequenced regions in HIV-1 gag using PBMC samples derived from the time of acute infection (day 18) and the third STI (day 1,170). Although sequence changes were identified in three of the seven epitopes located within HIV-1 gag, there was an even greater number of amino acid changes in the flanking regions that did not contain targeted CD8+ T-cell epitopes (Fig. 3a). Phylogenetic analysis of autologous gag sequences from these time points (day 18 acute infection, and day 1,170 3rd STI) indicated that a distinct and unrelated second strain of HIV-1 had emerged (Fig. 3b). Additional sequencing of virus derived from intermediate time points during the first STI (day 606) and the second STI (day 1,021) confirmed these results, which were verified by an independent investigator (data not shown). These data showed that the early samples (day 18 and day 606) represented one strain of HIV-1 (referred to as virus A), whereas later samples (day 1,021 and day 1,170) represented a distinct second strain of HIV-1 (referred to as virus B) that became detectable during the end of the second STI and persisted during the third and fourth STI.

Figure 3: Sequence and phylogenetic analysis of viruses from subject AC-06.

a, Gag sequences from subject AC-06 show high amino acid diversity. Consensus sequences were derived from several clones (minimum 4, mean 8) spanning each of the individual PCR fragments of the HIV-1 gag open reading frame. The sequences shown reflect the predominant viral populations present at day 18 and day 1,170. Boxes indicate the seven HLA-A03- or B07-restricted Gag epitopes targeted by this subject. b, HIV gag sequences from subject AC-06 during acute (day 18) and chronic (day 1,170) infection cluster independently. Sequences from 17 HIV-1 infected persons from the Boston area were aligned27. The neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree indicates that two distinct viruses are present in subject AC-06 at these different times after infection (bootstrap values >60 are shown). Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of sequences included for each subject and where available the number of acute (ac) or chronic (ch) stage sequences included. Scale bar indicates the genetic distance along the branches. c, Virus B predominates in plasma of subject AC-06 on day 1,005. Specific PCR primers for virus A and virus B were generated based on unique nucleotide substitutions present in the two viruses in a region of gag. RT–PCR was carried out on plasma viral RNA isolated throughout infection. Consensus clade-B-specific primers successfully amplify products at all time points, verifying sample integrity. Only virus-A-specific primers amplify product from plasma samples taken during the first 972 d of infection; by contrast, only virus-B-specific primers amplify product from samples taken from day 1,005 onwards.

Overall, the sequences of virus A and virus B were significantly different, showing 12% heterogeneity in amino acid sequence (on the basis of >80% sequence coverage of whole HIV genomes). BLAST searches of the HIV database also confirmed the uniqueness of both viruses. By contrast, viruses A and B themselves were found to vary only minimally (<0.3% amino acid heterogeneity) over time between day 18 and day 606 (virus A) and between day 1,021 and day 1,170 (virus B). Similarly, the viral diversity observed to develop in other subjects undergoing STIs over a similar time frame was also significantly more limited (data not shown). Thus, the sequence variations observed between virus A and virus B were not the result of viral evolution in several targeted CD8+ T-cell epitopes, but rather the emergence of a new HIV-1 clade-B strain in the study subject at a time when the initial virus was well controlled. An additional maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis showed that it is highly unlikely that virus A and virus B arose from the same lineage within the context of the Boston cohort (see Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, there was no evidence for recombination between virus A and virus B in subject AC-06 (data not shown). Both strains were most closely related to HIV-1 clade-B sequences and possessed an R5 phenotype as determined by their differential infection in U87-CD4-CCR5, U87-CD4-CXCR4 and MT2 cells (ref. 20 and data not shown).

The above data suggest that either dual infection with viruses A and B occurred during the primary HIV-1 infection or there was subsequent superinfection with virus B. Review of medical records indicated that subject AC-06 experienced symptoms including fever, lymphadenopathy and night sweats in the month preceding the first detection of virus B. In addition, this subject reported an unprotected sexual risk exposure with an anonymous partner 4–8 weeks before the beginning of symptoms. The clinical data were thus consistent with exposure to another virus. To define further the time of infection with virus B, virus-specific nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primer sets corresponding to unique gag nucleotide sequences were used to track both viruses throughout infection (see Supplementary Table I). Nested PCR with reverse transcription (RT–PCR) of plasma virus showed that virus A was the only detectable virus at the time of acute infection (day 4), during the first STI (day 606), and throughout most of the second STI (until day 972). In marked contrast, after the sudden increase in viraemia (day 1,005, Fig. 1a), the only virus detected in plasma was virus B (Fig. 3c). We carried out a similar analysis on viral DNA derived from PBMCs. Primers specific for virus A successfully amplified products from PBMC samples taken throughout infection, albeit less consistently from later time points when virus B predominated in plasma (data not shown). By contrast, primers specific for virus B successfully amplified products only from PBMC samples taken after day 1,021 (data not shown). Thus, the clinical and PCR data are most consistent with superinfection rather than with dual infection at the time of primary infection.

We next compared the sequence integrity of the CD8+ T-cell epitopes that were targeted before emergence of virus B to assess the impact of viral variability on immune recognition. Autologous sequences of virus A and virus B were amplified successfully for all regions except portions of env and nef, for which high sequence diversity limited amplification with the available primers (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Table II). Sixteen of the twenty-five epitopes were sequenced, as well as three new epitopes targeted for the first time after emergence of virus B. Recognition of autologous epitopes was assessed using PBMCs from several time points before and after emergence of virus B (Table 1) using an IFN-γ Elispot assay.

Table 1 Viral sequence analysis and autologous epitope recognition by subject AC-06

For 9 of the 16 sequenced epitopes targeted at the time of loss of immune control, either the epitope sequence was conserved completely (7 epitopes) or the virus B variant differed but was equally well recognized by CD8+ T cells derived from early and late time points (two epitopes), as assessed through peptide titration Elispot assays (ref. 21 and Supplementary Fig. 3). CD8+ T-cell responses to eight of these nine epitopes persisted after emergence of virus B (Table 1). The exception was a declining HLA-A3-restricted response to p17 Gag (KIRLRPGGK); this sequence was identical in both viruses, but virus B had an arginine to threonine mutation at position C + 2 that may have impaired antigen processing22.

For 7 of the 16 epitopes evaluated by sequence analysis, there were sequence changes in the CD8+ T-cell epitopes that were associated with declining CD8+ T-cell responses (Table 1) and decreased recognition by the established immune response (Supplementary Fig. 3). Indeed, comparison of the variability observed within each of these 16 sequenced epitopes to clade-B sequences present in the Los Alamos database showed a similar trend, with those epitopes conserved between virus A and virus B showing a greater degree of conservation than those that varied. Sequence data were not obtained for nine epitopes, for which five responses declined and four persisted (data not shown). Notably, the immunodominant CD8+ T-cell epitope GPGHKARVL in p24 Gag was present in both viruses, indicating that maintained responses against this epitope were not sufficient to prevent emergence of virus B9,18.

Optimal CD4+ T-cell responses in this individual have not been defined and thus the impact that this viral diversity has on maintenance of HIV-specific CD4+ T-cell responses is unknown. After emergence of virus B, however, Gag-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferative responses did rebound to significant levels, suggesting persistent cross-recognition. Notably, a marked decline in Gag-specific CD4 proliferative responses and CD4+ T-cell counts was observed during the fourth STI in the setting of increased viral replication (Fig. 1). With respect to humoral responses, as stated previously, only weak neutralizing antibody responses specific to virus A were detectable before superinfection. But these virus-A-specific responses were lost after superinfection with virus B (titre < 4) and were not crossreactive against virus B (Supplementary Table III). After emergence of virus B, virus-B-specific neutralizing antibody responses developed for the first time, with titres reaching 40. But virus B subsequently escaped from these virus-B-specific neutralizing antibody responses (titre < 4). These data show that neutralizing antibodies to virus B were lacking at the time of superinfection but were produced later, potentially contributing to viral evolution and neutralization escape.

In addition to a loss of immune responses at the time of emergence of virus B, at least three new CD8+ T-cell responses within HIV-1 Gag and Env were detectable for the first time after superinfection, including two previously described CD8 epitopes and one newly described epitope in HIV-1 Gag. Fine mapping of the new response showed that it was directed against an HLA-B7-restricted epitope (YPLASLRSL). Comparison of virus A and B sequences in this region indicated that the insertion of a proline at position 3 of this epitope (YPPLASLRSL) in virus A resulted in a variant that apparently had prevented the initial presentation of this region to the immune system (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3). A response to this region was detectable for the first time when virus B predominated (Table 1). Similarly, for two additional epitopes that were recognized for the first time with emergence of virus B, the autologous variants of virus B were recognized at lower peptide concentrations than were the virus A variants (Supplementary Fig. 3). Thus, new CD8+ T-cell responses were capable of being induced in the setting of chronic persistent viral infection.

Our studies in a single individual indicate that virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses that control replication of one strain of HIV-1 may not be sufficiently potent to prevent superinfection with a second virus of the same clade. It must be emphasized, however, that superinfection in an individual already infected with HIV-1 may be different from infection in a person with healthy immune system. In line with studies showing superinfection with a different HIV-1 clade23,24, our results provide a potential explanation for the emergence of a growing number of recombinant viruses worldwide25. In the case described here, although there was only roughly 12% difference in overall sequence, at least half of the targeted CD8 epitopes were not shared between the two viruses, both of which were acquired in North America. Although the immunodominant CD8+ T-cell epitope was conserved in both viruses, control of virus B was not achieved until additional epitopes were targeted, which suggests that subdominant responses have a role in immune control. Our study does show the ability of the immune system to generate CD8+ T-cell responses against epitopes that have not been previously presented, which indicates that therapeutic immunization in chronic infection may be possible. Further detailed dissection of immune responses in persons who control viraemia and then lose this control should provide important insights regarding the breadth, magnitude and phenotype of HIV-1-specific immune responses that may be necessary to provide broad, cross-protective immunity.