Long-term haematopoietic reconstitution by Trp53-/-p16Ink4a-/-p19Arf-/- multipotent progenitors (original) (raw)

Main

Bmi1 is necessary for the maintenance of adult HSCs and neural stem cells7,8,9.The p16 Ink4a /p19 Arf locus is one of the major targets repressed by Bmi1 (refs 8, 10). In neural stem cells, p16 Ink4a or p19 Arf deficiency partially restored the ability of _Bmi1_-deficient stem cells to self-renew7,11. We analysed the effect of individually deleting either p16 Ink4a , p19 Arf or Trp53 in _Bmi1_-deficient mice and found that in the blood system, Trp53 deficiency, but not p19 Arf or p16 Ink4a deficiency, partially rescues _Bmi1_-/- HSCs (Supplementary Figs 2 and 3 and Supplementary Table 1).

Because the deletion of either the p16 Ink4a /p19 Arf locus12 or Trp53 seems to have a role in the rescue of HSCs in _Bmi1_-deficient mice, we examined the impact of deleting p19 Arf , p16 Ink4a /p19 Arf , Trp53 and p16 Ink4a /p19 Arf /Trp53 on the mature cells of the haematopoietic system. Analysis of the liver, spleen, bone marrow and peripheral blood from mutant mice showed no defects in the output of mature cells (Supplementary Figs 4 and 5). Neutrophil, lymphocyte and monocyte counts from mutant mice were normal (Supplementary Fig. 4), as were haematocrit and platelet counts (data not shown). In the bone marrow of mutant mice, levels of B220+ cells, Ter119+ cells, Gr-1+ cells and Mac-1+ cells were normal (Supplementary Fig. 4). Analysis of spleen and thymus also showed normal levels of mature haematopoietic cells (Supplementary Fig. 4). Therefore, the deletion of p19 Arf , Trp53, p16 Ink4a /p19 Arf and p16 Ink4a /p19 Arf /Trp53 does not seem to compromise haematopoietic differentiation.

We wished to know whether p16 Ink4a , p19 Arf or Trp53 regulate self-renewal in blood cells. To do this, limiting dilution analysis was done to determine the frequencies of bone marrow cells responsible for long-term haematopoietic reconstitution in mutant mice. Whole bone marrow cells from approximately 8-week-old wild-type and mutant mice were injected at different doses into lethally irradiated recipient mice along with a radioprotective dose of recipient bone marrow (Supplementary Table 2). In p19 _Arf_-/-, _Trp53_-/- and p16 _Ink4a_-/-p19 _Arf_-/- bone marrow the frequency of cells responsible for long-term reconstitution was not significantly different from that of wild-type mice (Table 1). These results agree with previous studies that show that in young mice, deficiency of p16 Ink4a , p19 Arf , Trp53 and both p16 Ink4a and p19 Arf does not significantly affect the long-term reconstitution frequency of HSCs and has more of an effect in the context of stem-cell ageing13,14,15. Notably, the frequency of long-term reconstituting cells in triple mutant bone marrow was at least 10-fold higher than that of wild-type bone marrow (Table 1).

Table 1 Frequency of long-term reconstituting cells determined by limiting dilution analysis

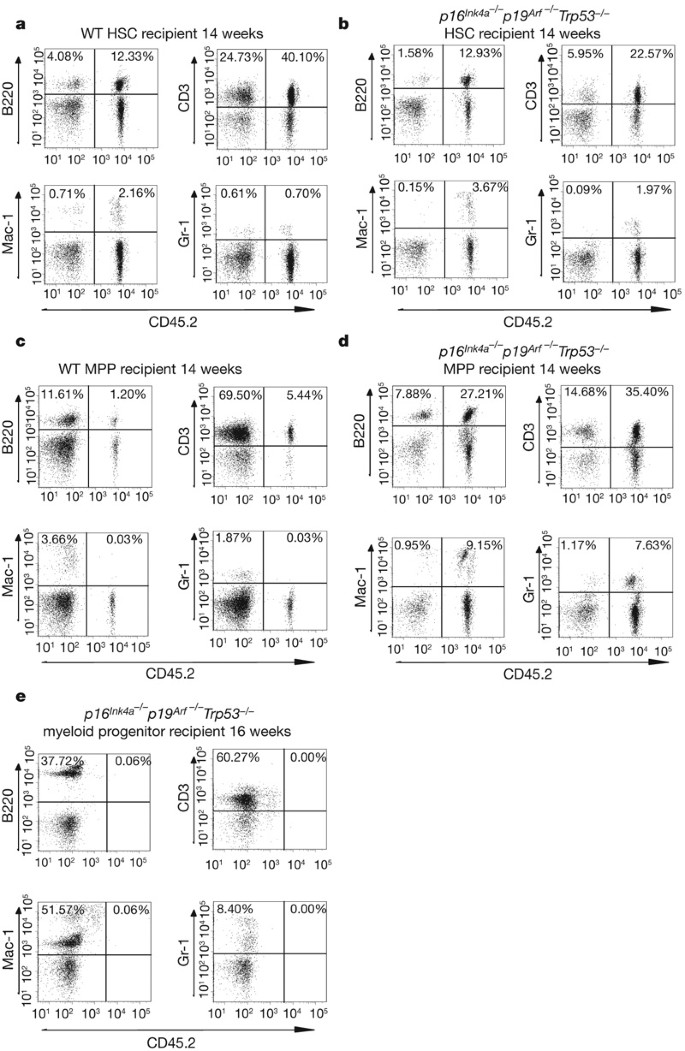

Our results suggest that triple deletion of p16 Ink4a , p19 Arf and Trp53 caused a striking increase in the frequency of long-term blood-repopulating cells. We therefore decided to examine further the bone marrow of triple mutant mice. Because there was only a modest increase in the frequency of bone marrow cells with a phenotype of HSCs in triple mutant mice (Fig. 1a, b), we concluded that the increased repopulating activity in the triple mutant mice was probably not due to the expansion of the overall numbers of HSCs but rather to acquisition of stem-cell-like properties by other cells. Therefore, we compared the long-term reconstitution capacity of both HSCs (defined as CD150+Sca-1+c-kit+CD48-Lin-) and multipotent progenitors (defined as Sca-1+c-kit+CD150-CD48-Lin-) from wild-type and triple mutant mice. We performed two independent experiments where we injected either 100 or 500 HSCs or multipotent progenitors from four different triple mutant mice into lethally irradiated recipients along with a radioprotective dose of recipient-type bone marrow. Contribution to the generation of lymphocytes, monocytes and granulocytes after 12 weeks is an indicator of long-term reconstitution1. Consistent with previous reports4,16,17, wild-type HSCs, but not multipotent progenitors, contributed to the long-term generation of monocytes and granulocytes (Fig. 2a, c). Recipient mice injected with HSCs from the bone marrow of triple mutant mice showed long-term reconstitution for multiple lineages (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 3). Notably, recipient mice injected with multipotent progenitors from each of the four triple mutant mice were also long-term multi-lineage reconstituted (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 3). Contribution to haematopoiesis was observed at 14 to 20 weeks (Fig. 2b, d and Supplementary Figs 6 and 7). This suggests that the greater frequency of cells capable of long-term reconstituting ability observed during limiting dilution analysis of triple mutant bone marrow was due to both the HSC and multipotent progenitor populations of the mutant mice. On secondary transplantation of approximately 2 × 106 whole bone marrow cells from recipient mice engrafted for 20 weeks with 100 triple mutant HSCs or multipotent progenitors, we observed contribution to donor CD3+ lymphocytes and Gr-1+ myeloid cells in lethally irradiated recipients (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 8) 12 weeks after transplantation, indicating that cells with the phenotype of multipotent progenitors in triple mutant mice can generate mature blood cells of both lymphoid and myeloid lineages for extended periods of time.

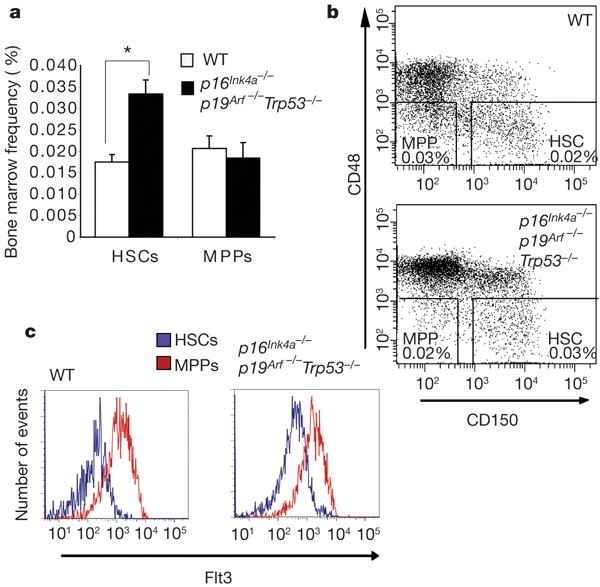

Figure 1: Immunophenotypic frequency of HSCs and multipotent progenitors in wild-type and p16 Ink4a-/- p19 Arf-/- Trp53 -/- mice.

a, The immunophenotypic frequency of HSCs (CD150+Sca-1+c-kit+CD48-Lin-) and multipotent progenitors (MPPs; Sca-1+c-kit+CD150-CD48-Lin-) was assessed by flow cytometry. There was a modest increase in HSC frequency in p16 Ink4a-/- p19 Arf-/- _Trp53_-/- mice compared to wild type (WT) and no significant difference in the multipotent progenitor frequency. The averages of wild-type (n = 7) and triple mutant mice (n = 5) are shown. Asterisk, P < 0.005 (Student’s _t_-test). Error bars denote s.e.m. b, A representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plot gated on Sca-1+c-kit+Lin- bone marrow cells depicting HSC and multipotent progenitor frequency. c, Mean intensity fluorescence of Flt3 expression of wild-type (n = 9) and triple mutant (n = 2) HSCs and multipotent progenitors.

Figure 2: Long-term multi-lineage reconstitution by HSCs and multipotent progenitors from p16 Ink4a -/- p19 Arf -/- Trp53 -/- mice.

a, Long-term reconstitution by double-sorted HSCs (CD150+Sca-1+c-kit+CD48-Lin-) from wild-type mice. b, Transplantation of HSCs from p16 Ink4a-/- p19 Arf-/- _Trp53_-/- mice results in long-term multi-lineage reconstitution of recipient mice when analysed 14–20 weeks after transplantation (four of four mice). c, Double-sorted multipotent progenitors (Sca-1+c-kit+CD150-CD48-Lin-) from wild-type mice are only capable of contributing to long-lived lymphocyte B220+ and CD3+ populations and not to short-lived myeloid Mac-1+ and Gr-1+ populations. d, Transplanted double-sorted multipotent progenitors from triple mutant mice also resulted in long-term multi-lineage reconstitution of recipient mice when analysed 14–20 weeks after transplantation (four of four mice). e, Double-sorted c-kit+Sca-1-Lin- myeloid progenitors do not contribute to short-lived myeloid Mac-1+ and Gr-1+ populations.

Immunophenotypic analysis by flow cytometry showed that there was at most twice the frequency of HSCs by phenotype (CD150+Sca-1+c-kit+CD48-Lin-) and a relatively identical frequency of multipotent progenitors by phenotype (Sca-1+c-kit+CD150-CD48-Lin-) in p16 _Ink4a_-/-p19 _Arf_-/-_Trp53_-/- bone marrow compared to wild-type marrow (Fig. 1a, b). We also used Flt3, which is expressed by normal multipotent progenitors but not HSCs, as an alternative marker to distinguish HSCs from multipotent progenitors5,6. We found that the wild-type and triple mutant Sca-1+c-kit+CD150-CD48-Lin- cells expressed higher levels of this marker than did cells with a stem cell phenotype of CD150+Sca-1+c-kit+CD48-Lin- (Fig. 1c). This further suggests that the phenotype of HSCs and multipotent progenitors is not altered in the triple mutant mice.

Next, we performed three independent in vitro proliferation experiments to provide evidence that triple mutant CD150+Sca-1+c-kit+Flt3+CD48-Lin- cells were indeed multipotent progenitors and to understand the mechanisms by which their lifespan was extended. We used culture conditions that allow HSCs to expand in vitro in StemSpan serum-free media containing the growth factors SCF, TPO, IGF-2, FGF-1 and Angptl3 (STIFA media)18,19,20. When cultured in STIFA medium, wild-type multipotent progenitors proliferated fivefold less than wild-type HSCs (Fig. 3a), and the addition of Flt3 ligand to the media doubled the proliferative rate of the multipotent progenitors (Fig. 3a). Notably, when cultured in STIFA media, triple mutant multipotent progenitors also proliferated about fivefold less than triple mutant HSCs and still responded to Flt3 ligand (Fig. 3a). This suggests that triple mutant multipotent progenitors, although capable of long-term reconstitution, display an in vitro functional behaviour that mirrors that of wild-type multipotent progenitors and are different from HSCs. In two independent experiments we also determined the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis in STIFA media in the case of HSCs and STIFA media plus Flt3 ligand for multipotent progenitors, measured by annexin V staining. Triple mutant HSCs and multipotent progenitors had threefold and twofold decreases, respectively, in the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis compared to wild-type cells (Supplementary Fig. 9). The proliferation advantage of triple mutant HSCs and multipotent progenitors could be partly due to a decrease in the rate of apoptosis in the triple mutants compared to their wild-type counterparts.

Figure 3: In vitro proliferation and colony formation of wild-type and triple mutant HSCs and multipotent progenitors.

a, Proliferation of wild-type and triple mutant HSCs and multipotent progenitors in expansion media. Wild-type and triple mutant HSCs are responsive to cytokines that promote their expansion and proliferate considerably better than wild-type and triple mutant multipotent progenitors in serum-free StemSpan media containing SCF, TPO, IGF-2, FGF-1 and Angptl3 (STIFA) media. Wild-type and triple mutant multipotent progenitors show a doubling in their proliferation rates with the addition of Flt3 ligand to the STIFA media. Five cells were double-sorted into U-bottom 96-well plates. Replicates of at least 21 wells for each experimental group were counted. b, Triple mutant multipotent progenitors show an increase in the number of secondary colonies that they form compared to wild-type multipotent progenitors in Methocult and Methocult plus media, demonstrating their proliferative advantage. Triple mutant multipotent progenitors are also very responsive to the additional cytokines IL-11, GM-CSF, Flt3 ligand and TPO added to the Methocult media and can form secondary colonies even better than wild-type HSCs. Single cells were double-sorted into U-bottom 96-well plates for the colony formation experiments. Replicates of at least 20 wells were scored in the methylcellulose colony formation experiments. For a and b: asterisk, P < 0.005; double asterisk, P < 0.0001 (Student’s _t_-test). Error bars denote s.e.m. c, Representative images of wild-type and triple mutant colonies from single double-sorted HSCs and multipotent progenitors taken at ×25 magnification.

To examine further the proliferative capacity of wild-type and triple mutant HSCs and multipotent progenitors we observed the colony-forming capacity of single cells double-sorted into 96-well plates in Methocult GF M3434 media (Methocult) and Methocult GF M3434 media supplemented with interleukin (IL)-11, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), TPO and Flt3 ligand (Methocult plus) (Fig. 3b) in three independent experiments. Triple mutant HSCs formed more secondary colonies than wild-type HSCs in Methocult plus media, whereas the triple mutant multipotent progenitors formed significantly more colonies than wild-type multipotent progenitors in both Methocult plus and Methocult media (Fig. 3b). This clearly shows that triple mutant multipotent progenitors have an enhanced proliferative capacity, and in the Methocult plus media they proliferate and form secondary colonies better than even wild-type HSCs (Fig. 3b, c).

We next asked whether loss of the p16 Ink4a /p19 Arf and Trp53 loci conferred long-term reconstituting ability on all proliferating blood cells. To do this, we transplanted three recipient mice with 100 c-kit+Sca-1-Lin- myeloid progenitors, a more differentiated progenitor population. We could not detect contribution to mature lineages at 4 weeks and 10 weeks, and we stopped analysis at 16 weeks (Fig. 2e). Next, we transplanted eight recipient mice with 500 or 1,000 triple mutant common myeloid progenitors and another eight recipient mice with 500 or 1,000 granulocyte–macrophage progenitors21. After 3 weeks, we were unable to detect mature myeloid cells that were descended from the transplanted common myeloid progenitors or granulocyte–macrophage progenitors (Supplementary Table 3). These results suggest that as progenitor cells mature the constraints on self-renewal increase (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The cellular hierarchy seen in many tissues with self-renewing stem cells and short-lived progenitors probably evolved to limit the number of cells that can accumulate oncogenic mutations. Our data demonstrates that loss of both p16 Ink4a /p19 Arf and Trp53 loci results in substantial expansion of self-renewing cells. Our results suggest that triple mutant multipotent progenitors have acquired long-term reconstituting ability, implying that the compound deletion of p16 Ink4 , p19 Arf and Trp53 removes constraints limiting self-renewal in early progenitors2. However, triple mutant common myeloid progenitors and granulocyte–macrophage progenitors, more differentiated progenitor cells, still have limited lifespans (Supplementary Fig. 1), suggesting that there must be other genetic pathways that also prevent self-renewal in mature progenitors. This further supports the notion that there are multiple genetic determinants that regulate the frequency of self-renewing haematopoietic cells in vivo3. This expansion of long-lived cells potentially reveals a cellular mechanism by which these genes contribute to oncogenesis and may explain why they, or other components of their regulatory pathways, are so commonly mutated or dysregulated in multiple tumour types22,23,24,25,26. The regulation of self-renewal in wild-type HSCs by epigenetically repressing the p16 Ink4a /p19 Arf locus and Trp53 pathway, in contrast to that of triple mutant multipotent progenitors achieved by genetic deficiency of the p16 Ink4a /p19 Arf locus and Trp53, hints at differences in the regulation of self-renewal in normal cells and self-renewing cancer cells that harbour mutations in these genes. Such differences could be exploited as therapeutic targets.

Methods Summary

Flow cytometry

Isolation and analysis of bone marrow, thymus, spleen and peripheral blood have been previously described4,6,21 and additional details can be found in Methods.

Cell proliferation, apoptosis and colony formation

Proliferation of HSCs was assayed via in vitro culture in STIFA expansion media20 and in the case of multipotent progenitors in STIFA media with or without Flt3 ligand. Apoptosis during in vitro expansion of HSCs and multipotent progenitors was assayed by annexin V and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. Colony formation was performed as previously described27.

Online Methods

Mice

_Trp53_-/- mice (B6.129S2-Trp53 tm1Tyj ) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory, p16 Ink4a-/- mice (FVB/N.129-Cdkn2a tm2Rdp ) and p16 Ink4a-/- p19 Arf-/- mice (B6.129-Cdkn2a tm1Rdp ) were obtained from Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium (NCI-Frederick). p19 Arf-/- mice were obtained from C. Sherr. Bmi1+/- mice were obtained from T. Magnuson. All mice were bred with BA mice (C57Bl/Ka-CD45.2/Thy1.1) at least five times, and verified for Thy1.1, H-2b and CD45.2 homozygosity by peripheral blood analysis using flow cytometry. Recipient mice in transplant assays were adult C57Bl/Ka-CD45.1/Thy1.2 mice. All mice used for this study were maintained at the University of Michigan Animal Facility or Stanford Animal Facility in accordance with the guidelines of both Institutional Animal Care Use Committees.

Flow cytometry

Antibodies used for sorting bone marrow cells and analysis were lineage markers (CD3, CD5, CD8, Gr-1, B220 and Ter119), Sca-1, c-kit, CD135 (Flt3), FcγR (CD16/CD32), CD34, IL-7R, CD150 and CD48. Cells were analysed or sorted using a Vantage fluorescence-activated cell sorter (BD Biosciences) or FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences). For analysis of wild-type and mutant mice in a Bmi1-deficient background we used Lin-CD135-Thy-1.1loSca-1+c-kit+ HSCs6. For analysis and sorting of wild-type and triple mutant HSCs and multipotent progenitors we used CD150+CD48-Sca-1+Lin-c-kit+ HSCs and CD150-CD48-Sca-1+Lin-c-kit+ multipotent progenitors as previously described4,16,17. For sorting of wild-type and triple mutant myeloid progenitors we used c-kit+Sca-1-Lin- myeloid progenitors, whereas for further fractionation we used CD34+FcγRloIL-7R-Sca-1-Lin-c-kit+ common myeloid progenitors and CD34+FcγRhiIL-7R-Sca-1-Lin-c-kit+ granulocyte–macrophage progenitors21. For lineage analysis, both bone marrow cells and splenocytes were stained with antibodies against Gr-1, Mac-1, CD3, B220 and Ter119, and thymocytes with antibodies against CD3, CD4 and CD8. For peripheral blood analysis, red blood cells were lysed with hypotonic buffer, and nucleated cells were stained with antibodies against CD45.2, Gr-1, Mac-1, CD3 and B220. Antibodies were directly conjugated or biotinylated and purchased from e-Bioscience, BD Biosciences, or Biolegend.

Long-term competitive reconstitution

C57Bl/Ka-CD45.1/Thy1.2 congenic mice were lethally irradiated (1,140 rad) at a dose rate of approximately 3 Gy min-1, delivered in two doses 4 h apart. The next day, mice were competitively reconstituted by retro-orbital venous sinus injection of whole bone marrow cells from donor mice mixed with a radioprotective dose of 2 × 105 bone marrow cells from unirradiated C57Bl/Ka-CD45.1/Thy1.2 mice. Peripheral blood was drawn monthly up to 20 weeks to monitor reconstitution by donor type (CD45.2) myeloid and lymphoid cells, as described above. Mice that had more than 1% donor-derived (Ly5.1+) cells in both lymphoid (CD3+ and B220+) and myeloid (Gr-1+ and Mac-1+) subpopulations were considered to be repopulated by donor cells. The secondary bone marrow transplant was performed using 1 × 106 or 2 × 106 whole bone marrow cells. Frequency of long-term reconstituting cells from limiting dilution experiments was calculated using L-Calc software (StemCell Technologies).

In vitro proliferation, colony formation and annexin V analysis

We double-sorted 1 or 5 wild-type or triple mutant HSCs or multipotent progenitors into U-bottom 96-well plates containing 200 μl of StemSpan serum-free media (StemCell technologies) supplemented with 10 μg ml-1 of heparin (Sigma), 10 ng ml-1 mouse SCF, 20 ng ml-1 mouse TPO, 20 ng ml-1 mouse IGF-2, 100 ng ml-1 mouse Angptl3 (all from R&D) and 10 ng ml-1 human FGF-1 as previously described18,19,20. In the case of both wild-type and triple mutant multipotent progenitors we also clone-sorted 1 or 5 cells into the StemSpan serum-free media supplemented as above with the addition of 30 ng ml-1 mouse Flt3 ligand (R&D). The cell counts were performed on day 12.

For colony formation we double-sorted single wild-type or triple mutant HSCs or multipotent progenitors into U-bottom 96-well plates containing 100 μl of Methocult GF M3434 media (StemCell Technologies) or 100 μl of Methocult GF M3434 media supplemented with 10 ng ml-1 mouse IL-11, 50 ng ml-1 mouse GM-CSF, 50 ng ml-1 mouse TPO and 10 ng ml-1 mouse Flt3 ligand (all from R&D) as previously described27. Colonies were scored on day 10 of culture. Pictures of colonies were taken with a Leica DMI 6000B microscope using Image Pro-plus software version 5.1.

For annexin V analysis of apoptotic cells we sorted 1,000 wild-type or triple mutant HSCs into StemSpan serum-free media supplemented with the cytokines SCF, TPO, IGF-2, FGF-1 and Angptl3, or 1,000 wild-type or triple mutant multipotent progenitors sorted into StemSpan serum-free media supplemented with the cytokines SCF, TPO, IGF-2, FGF-1, Angptl3 and Flt3 ligand. The cells were cultured for 12 days and stained with annexin V-Fitc (BD Biosciences) and the viability marker DAPI (Molecular Probes).

References

- Morrison, S. J. & Weissman, I. L. The long-term repopulating subset of hematopoietic stem cells is deterministic and isolatable by phenotype. Immunity 1, 661–673 (1994)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Clarke, M. F. & Fuller, M. Stem cells and cancer: two faces of eve. Cell 124, 1111–1115 (2006)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Morrison, S. J. et al. A genetic determinant that specifically regulates the frequency of hematopoietic stem cells. J. Immunol. 168, 635–642 (2002)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kiel, M. J. et al. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell 121, 1109–1121 (2005)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Adolfsson, J. et al. Upregulation of Flt3 expression within the bone marrow Lin-Sca1+c-kit+ stem cell compartment is accompanied by loss of self-renewal capacity. Immunity 15, 659–669 (2001)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Christensen, J. L. & Weissman, I. L. Flk-2 is a marker in hematopoietic stem cell differentiation: a simple method to isolate long-term stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 14541–14546 (2001)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Molofsky, A. V. et al. Bmi-1 dependence distinguishes neural stem cell self-renewal from progenitor proliferation. Nature 425, 962–967 (2003)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Park, I.-K. et al. Bmi-1 is required for maintenance of adult self-renewing haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 423, 302–305 (2003)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Lessard, J. & Sauvageau, G. Bmi-1 determines the proliferative capacity of normal and leukaemic stem cells. Nature 423, 255–260 (2003)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Jacobs, J. J., Kieboom, K., Marino, S., DePinho, R. A. & van Lohuizen, M. The oncogene and Polycomb-group gene bmi-1 regulates cell proliferation and senescence through the ink4a locus. Nature 397, 164–168 (1999)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Molofsky, A. V., He, S., Bydon, M., Morrison, S. J. & Pardal, R. Bmi-1 promotes neural stem cell self-renewal and neural development but not mouse growth and survival by repressing the p16Ink4a and p19Arf senescence pathways. Genes Dev. 19, 1432–1437 (2005)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Oguro, H. et al. Differential impact of Ink4a and Arf on hematopoietic stem cells and their bone marrow microenvironment in Bmi1-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2247–2253 (2006)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Janzen, V. et al. Stem-cell ageing modified by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a . Nature 443, 421–426 (2006)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Stepanova, L. & Sorrentino, B. P. A limited role for p16Ink4a and p19Arfin the loss of hematopoietic stem cells during proliferative stress. Blood 106, 827–832 (2005)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Dumble, M. et al. The impact of altered p53 dosage on hematopoietic stem cell dynamics during aging. Blood 109, 1736–1742 (2007)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kim, I., He, S., Yilmaz, O. H., Kiel, M. J. & Morrison, S. J. Enhanced purification of fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells using SLAM family receptors. Blood 108, 737–744 (2006)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Yilmaz, O. H., Kiel, M. J. & Morrison, S. J. SLAM family markers are conserved among hematopoietic stem cells from old and reconstituted mice and markedly increase their purity. Blood 107, 924–930 (2006)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zhang, C. C. & Lodish, H. F. Insulin-like growth factor 2 expressed in a novel fetal liver cell population is a growth factor for hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 103, 2513–2521 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zhang, C. C. & Lodish, H. F. Murine hematopoietic stem cells change their surface phenotype during ex vivo expansion. Blood 105, 4314–4320 (2005)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zhang, C. C. et al. Angiopoietin-like proteins stimulate ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem cells. Nature Med. 12, 240–245 (2006)

Article Google Scholar - Akashi, K., Traver, D., Miyamoto, T. & Weissman, I. L. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature 404, 193–195 (2000)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Berggren, P. et al. Detecting homozygous deletions in the CDKN2A(p16 INK4a)/ARF(p14 ARF ) gene in urinary bladder cancer using real-time quantitative PCR. Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 235–242 (2003)

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Esteller, M. et al. Hypermethylation-associated inactivation of p14ARF is independent of p16INK4a methylation and p53 mutational status. Cancer Res. 60, 129–133 (2000)

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Weber, A., Bellmann, U., Bootz, F., Wittekind, C. & Tannapfel, A. INK4a-ARF alterations and p53 mutations in primary and consecutive squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Virchows Arch. 441, 133–142 (2002)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Burke, L. et al. Prognostic implications of molecular and immunohistochemical profiles of the Rb and p53 cell cycle regulatory pathways in primary non-small cell lung carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 232–241 (2005)

ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zolota, V., Sirinian, C., Melachrinou, M., Symeonidis, A. & Bonikos, D. S. Expression of the regulatory cell cycle proteins p21, p27, p14, p16, p53, mdm2, and cyclin E in bone marrow biopsies with acute myeloid leukemia. Correlation with patients’ survival. Pathol. Res. Pract. 203, 199–207 (2007)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jamieson, C. H. et al. Granulocyte-macrophage progenitors as candidate leukemic stem cells in blast-crisis CML. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 657–667 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (to M.F.C).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Cellular and Molecular Biology Graduate Program, University of Michigan, 2966 Taubman Medical Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-0619, USA ,

Omobolaji O. Akala - Stanford Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine and Division of Hematology/Oncology, Internal Medicine, Stanford University, 1050 Arastradero Road, Palo Alto, California 93404, USA,

Omobolaji O. Akala, Dalong Qian & Michael F. Clarke - Department of Hematology/Oncology, Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, 1500 East Medical Center Drive, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, USA,

In-Kyung Park & Michael Pihalja - Division of Hematology/Oncology, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York 14642, USA,

Michael W. Becker

Authors

- Omobolaji O. Akala

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - In-Kyung Park

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Dalong Qian

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Michael Pihalja

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Michael W. Becker

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Michael F. Clarke

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence toMichael F. Clarke.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Akala, O., Park, IK., Qian, D. et al. Long-term haematopoietic reconstitution by _Trp53_-/-p16 _Ink4a_-/-p19 Arf-/- multipotent progenitors.Nature 453, 228–232 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06869

- Received: 20 December 2007

- Accepted: 25 February 2008

- Published: 16 April 2008

- Issue Date: 08 May 2008

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06869