European origin of placodont marine reptiles and the evolution of crushing dentition in Placodontia (original) (raw)

Introduction

Sauropterygia is the most diverse group of marine reptiles known1,2, with a variety of morphologies, ecologies and life history strategies that included the armoured, durophagous placodonts3, the predatory, shallow marine pachypleurosaurs and nothosaurs4, and the obligate swimming, viviparous plesiosaurs5. The group spanned around 180 myr, from the upper Lower Triassic to the Cretaceous–Palaeogene boundary (~245–65.5 mya6,7). Despite a global geological distribution and extensive fossil record (at least in Europe and Asia), it is still unclear where the clade originated, especially in the light of new discoveries from China8. Indeed, recent studies on pachypleurosaur phylogeny have suggested that despite the basal-most placodont being from Europe9, the clade may have originated in the Eastern Tethys10,11.

Here we present a new fossil skull of a juvenile sauropterygian from early Middle Triassic deposits of Winterswijk, the Netherlands. The fossil displays a suite of morphological characters identifying it as a stem placodont, emphasizing the role of the western Tethys (present day Europe and western Middle East) as a Middle Triassic marine reptile biodiversity hotspot (over 60 species, see compilation in Kelley et al.12). Although the skull lacks a heavily specialized dentition adapted for crushing hard-shelled prey, features such as an elongated palatine bone carrying a single row of pointed teeth strongly support that the new taxon is not only basal to all placodonts but, combined with its early stratigraphic age, also implies that the clade originated in Europe, spreading eastwards to the Eastern Tethys.

Although the placodonts have been studied since the 1830s13, the evolutionary origin of their highly specialized durophagous dentition has, until now, remained unknown. The new fossil thus provides the unique opportunity to describe, for the first time, the dentition of a stem placodont, and enables us to pinpoint the developmental changes necessary to create the transition from a generalized piercing dentition with interlocking conical teeth to the extreme form of crushing dentition found in these reptiles.

Results

Systematic palaeontology

Sauropterygia Owen, 1860; Placodontiformes tax. nov.; Palatodonta bleekeri gen. et sp. nov.

Etymology

_Palato_-, from the Latin ‘palatum’, meaning of the palatine bone; -donta, from the ancient Greek ‘odon’, meaning tooth; bleekeri, after the discoverer, Remco Bleeker, Goor, the Netherlands.

Holotype

TW480000470 (Fig. 1; Supplementary Figs S1 and S2), Twentse Welle Museum, Enschede, the Netherlands.

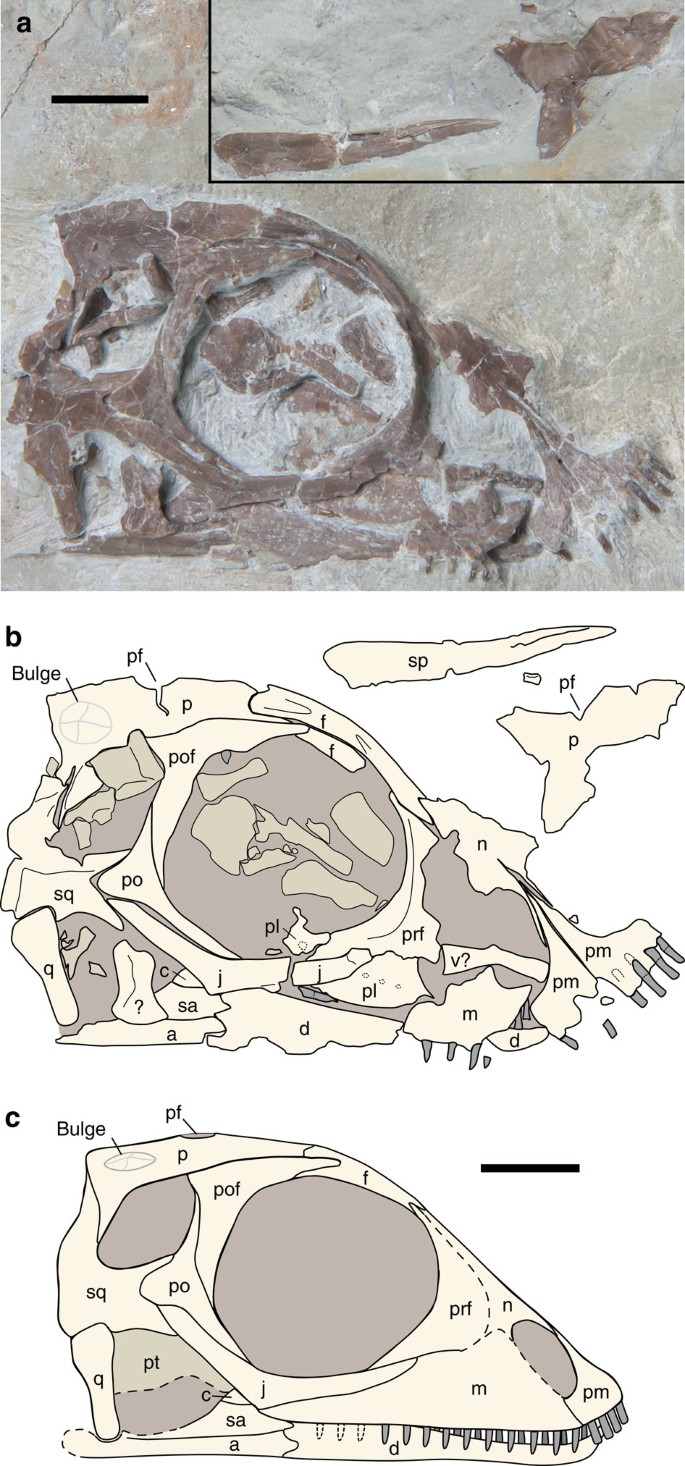

Figure 1: Palatodonta bleekeri genus et species nova holotype (TW480000470).

(a) Right lateral view of the specimen with disarticulated elements inset. (b) Labelled interpretation. (c) Reconstruction in lateral view. a, angular; c, coronoid; d, dentary; f, frontal; j, jugal; m, maxilla; n, nasal; p, parietal; pf, pineal foramen; pl, palatine; pm, premaxilla; po, postorbital; pof, postfrontal; prf, prefrontal; pt, pterygoid; q, quadrate; sa, surangular; sp, splenial; sq, squamosal; v, vomer. Scale bar, 3 mm.

Locality and horizon

Vossenveld Formation[14](/articles/ncomms2633#ref-CR14 "Hagdorn, H. & Simon, T. . Vossenveld formation. In LithoLex [Lithostratigraphisches Lexikon der Deutschen Stratigraphischen Kommission; online-database]. Hannover: BGR. Last updated 02.08.2010 [cited 4th March 2013], Record ID. 45. Available from: http://www.bgr.de/app/litholex/gesamt_ausgabe_neu.php?id=45

(2010) ."), Lower Muschelkalk (early Anisian), Winterswijk, the Netherlands. The horizon corresponds to layer 9 of Oosterink[15](/articles/ncomms2633#ref-CR15 "Oosterink, H. W. & Winterswijk, Geologiedeel II . De Triasperiode (geologie, mineralen en fossielen). Wetenschappelijke Mededeling van de Koninklijke Nederlandse Natuurhistorische Vereniging 178, 1–120 (1986) .").Diagnosis

Premaxilla large with distinct, narrow caudal process running between external nares and containing four blunt, peg-like, slightly procumbent teeth; a single row with at least 10 narrow, pointed teeth on the palatine; maxilla excluded from orbit and containing at least six pointed teeth; parietal with distinct caudolateral bulge located near dorsal margin of upper temporal fenestra; upper temporal fenestra laterally placed; jugal distinctly open L-shaped (boomerang-shaped); postorbital with distinct caudal process; quadratojugal absent; and excavated cheek region.

Description

The type and only known specimen is of a juvenile individual and has a high, blunt-snouted skull preserved in right lateral view, with the exception of the right parietal, the premaxillae and nasals, which are preserved in dorsal view (Fig. 1; for a detailed morphological description, see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Movie). The left parietal and left splenial are disarticulated, and preserved in a position just dorsal to the skull itself. The posterior part of the maxilla was removed during preparation, and extended caudally to meet the jugal, containing at least six pointed teeth (Supplementary Figs S1 and S2a). Palatodonta can be identified as a sauropterygian, as the premaxilla forms most of the snout rostral to external nares; a lacrimal being absent; an upper temporal fenestra and a lower temporal fenestra that open ventrally; a suborbital fenestra being absent; and teeth on the pterygoid flange being absent.

Several disarticulated elements that do not belong to the skull are preserved in this specimen, mostly within the orbit. We speculate that they are mostly from the postcranium, some of which are phalanges. In addition, a disarticulated tooth is visible between the mandible and jugal, probably originating from the right dentary, but may have been from the palatine or maxilla (Supplementary Fig. S2c). However, its robust appearance would indicate a caudal position in the skull as, in the dentary at least, posterior teeth are generally more massive (Fig. 2a). Another disarticulated tooth is visible at the dorsal margin of the orbit, in contact with the postfrontal. The teeth are heterogeneous, with different tooth-bearing elements displaying different tooth morphologies (Supplementary Fig. S2). The premaxillary teeth are blunt, peg-like, procumbent and have long roots, roughly equal to the length of the crowns. They are somewhat similar in morphology to that of the basal placodont Placodus, which would have used these teeth to pick up sessile, hard-shelled prey from the sea floor16. In fact, several placodont taxa exhibit procumbent, elongate teeth on the premaxilla, that is, Paraplacodus, Placodus, Protenodontosaurus and, to a lesser degree, Cyamodus hildegardis4. However, unlike Placodus, the premaxillary teeth of which are almost always disarticulated from the skull owing to a presumed fibrous attachment in the large alveolar spaces, the equivalent teeth in Palatodonta are articulated and firmly rooted within the bone16. All other teeth in Palatodonta are of extremely different morphology to those of placodonts, and are more similar to the expected plesiomorphic condition in that they are narrow and pointed instead of flattened and rounded (Supplementary Fig. S2).

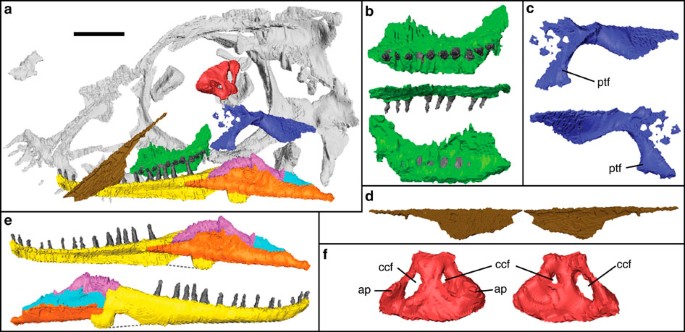

Figure 2: Three-dimensional reconstruction of μCT data showing obscured elements.

(a) Skull interior with obscured elements highlighted. red, basisphenoid; dark blue, pterygoid; green, palatine; brown, right splenial; yellow, dentary; pink, coronoid; light blue, surangular; orange, angular. (b) Palatine in ventral (top), lateral (middle) and dorsal (bottom) views. (c) Pterygoid in medial (top) and lateral (bottom) views. (d) Right splenial in lateral (left) and medial (right) views. (e) Right mandible in medial (top) and lateral (bottom) views. (f) Basisphenoid in dorsal (left) and ventral (right) views. ap, ascending process; ccf, cerebral carotid foramen; ptf, pterygoid flange. Scale bar, 3 mm, b–f not to scale.

Despite these differences, the skull of Palatodonta shows several similarities to the basal-most placodont Paraplacodus. The lower temporal fossa is open ventrally, with a highly excavated cheek region, the jugal is loosely ‘L-shaped’ and the quadrate is a simple bar, sutured dorsally to the squamosal. However, Palatodonta differs from other placodonts, with the exception of Placodus, in that the maxilla is excluded from the orbit and the jugal directly contacts the squamosal.

Additional micro-computed tomography (μCT) scanning provided insight into structures that were not visible on the outer surface of the slab. This revealed that only the right half of the skull was preserved and the left half was lost before fossilization. Using the μCT data, it was possible to reconstruct the entire right mandible, a large portion of the right palatine carrying a row of 10 pointed teeth, a large bone fragment interpreted as the right pterygoid, part of the basisphenoid and a variety of other, less diagnostic elements that most likely pertain to the braincase and the postcranium (Fig. 2).

The morphology of the palatine is particularly noteworthy, as it shares the condition of having a single row of teeth with the placodonts, although these are narrow and pointed in Palatodonta, instead of the round and flat shape typical for placodonts (Supplementary Fig. S3). In addition, the portion of the basisphenoid appears to be the hypophyseal pit, as it has a clear pair of foramina that we identify as the internal cerebral carotid foramina, similar to those seen in the placodonts Placodus and Placochelys17,18 and is consistent with the plesiomorphic condition seen in the basal diapsid Youngina19. There are two ascending processes lateral to the cerebral carotid foramina, similar to those present in Placodus17. The pterygoid is arched and edentulous, comparable to the condition seen in placodonts, providing a flange at the caudolateral margin of the palate.

Phylogenetic analysis

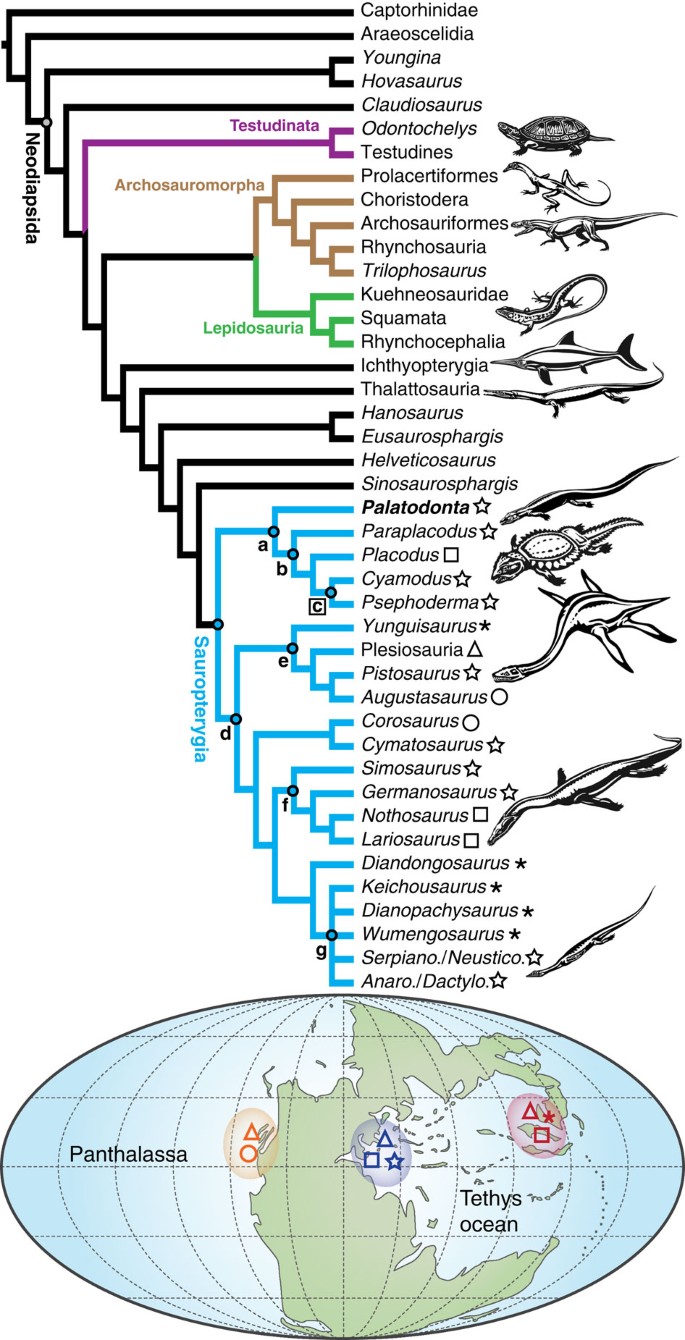

A phylogenetic analysis (see Methods and Supplementary Note 2 for Bremer and Bootstrap support and Supplementary Note 3 for character description) revealed Palatodonta to be sister taxon to Placodontia, supported by a single unambiguous synapomorphy (no. 51, pterygoids are generally shorter in this group compared with the palatines) and moderate bootstrap and Bremer support values (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. S4; see Methods section below). On the other hand, the new taxon is clearly separated from Placodontia by missing two unambiguous synapomorphies, that is, the complete lack of durophagous dentition (no. 63) and having more than three premaxillary teeth (no. 64) (Fig. 4).

Figure 3: Strict consensus tree showing the relationships of Sauropterygia within Diapsida combined with their geographic distribution.

All scores equal 100, apart from those shown (tree description shown in Methods; Supplementary Fig. S5). (a) Placodontiformes (new taxon). (b) Placodontia. (c) Cyamodontoidea. (d) Eosauropterygia. (e) Pistosauroidea. (f) Nothosauroidea. (g) Pachypleurosauria. Taxa are indicated by symbols on a simplified map of the Middle Triassic (adapted from Blakey[57](/articles/ncomms2633#ref-CR57 "Blakey, R. . Global Paleogeography Maps, Library of Paleogeography, Colorado Plateau Geosystems Inc. Website. http://cpgeosystems.com/paleomaps.html

(2012). [cited 4th March 2013]

http://www2.nau.edu/rcb7/

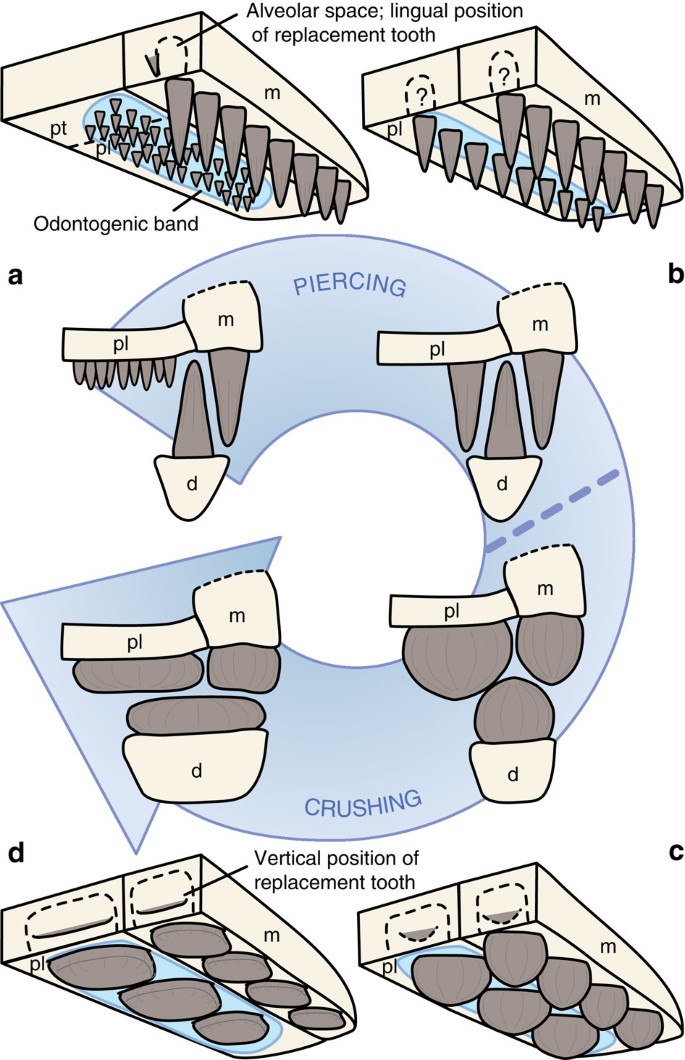

(2012) .") and McKie and Williams[58](/articles/ncomms2633#ref-CR58 "McKie, T. & Williams, B. . Triassic palaeogeography and fluvial dispersal across the northwest European Basins. Geol. J. 44, 711–741 (2009) .")) with the eastern Tethyan province (red), western Tethyan province (dark blue) and eastern Panthalassic province (orange) highlighted.Figure 4: Diagrammatic representation of tooth development of four taxa depicting the evolution from a pointed piercing dentition to a flattened crushing one.

(a) Generalized stem neodiapsid showing the plesiomorphic condition of denticles on the palate. (b) Palatodonta bleekeri gen. et sp. nov., with a single row of pointed teeth on the palatine, maxilla and dentary. (c) The basal placodont Paraplacodus, with rounded teeth, more adapted for a crushing diet. (d) Typical dentition of Placodus and cyamodontoid placodonts, showing highly flattened and enlarged crushing teeth. Note that mode of tooth replacement is not known in Palatodonta. In Paraplacodus, vertical tooth replacement is inferred by presence of dentary replacement teeth in PIMUZ T2805. Abbreviations as in Fig. 1.

The first search run on the matrix included all taxa, which yielded three most parsimonious trees (MPTs), with the shortest tree length of 566 steps (Consistency index (CI)=0.334, Retention index (RI)=0.659, Rescaled consistency index (RC)=0.220 and Homoplasy index (HI)=0.666). The strict consensus tree (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. S5a) recovered a sistergroup relationship between archosauromorph taxa and the lepidosaur lineage, but a monophyletic Lepidosauromorpha (that is, Lepidosauria plus Sauropterygia) was not supported. Instead, there is a basal grade including ichthyosaurs, thalattosaurs and several other diapsid taxa leading to Sauropterygia. The proposed Placodontiformes taxon nov. is sister to a monophyletic Eosauropterygia. It is noteworthy that the pistosauroid clade, which includes the plesiosaurs, was found to be the sister taxon to the remaining eosauropterygians. Note the basal position of turtles (Odontochelys and Testudines). The 50% majority rule consensus tree (Supplementary Fig. S5b) differs from the strict consensus only in the resolution within pachypleurosaurs.

The second search run on the matrix excluded Ichthyopterygia, yielding 85 MPTs, with the shortest tree length of 549 steps (CI=0.344, RI=0.666, RC=0.229 and HI=0.656). In comparison with the strict consensus tree in the first search run (Supplementary Fig. S5a), the exclusion of Ichthyopterygia led to a polytomy consisting of the archosaur and lepidosaur lineages, the turtles and the more highly nested diapsids (thalattosaurs to sauropterygians). The resolution is lower in Sauropterygia in the strict consensus compared with the first search run as well. In the 50% majority rule consensus (Supplementary Fig. S6b), Corosaurus is recovered as sister taxon to all remaining eosauropterygians, followed by the pistosauroid clade, with Cymatosaurus moving onto the stem of the latter.

The third run of the matrix excluded Ichthyopterygia and turtles (Odontochelys and Testudines), yielding 502 MPTs with the shortest tree length of 499 steps (CI=0.355, RI=0.673, RC=0.239 and HI=0.645). For this analysis, the number of trees retained was successively raised to 30 to acquire the shortest tree. Further increase to a 1,000 replicates and 100 retained trees per analysis led to the same topology of the strict consensus tree but differed in that all archosauromorph taxa were found in one polytomy in the 50% majority rule tree. This analysis yielded a poorly resolved strict consensus tree (Supplementary Fig. S7a) with polytomies in several sections of the cladogram. Especially, the resolution among the archosaur and lepidosaur lineages collapsed completely. The 50% majority rule consensus (Supplementary Fig. S7b) is somewhat better resolved, with sauropterygian ingroup relationships largely mirroring those shown in Supplementary Fig. S6b.

In the fourth analysis (with options set to 1,000 replicates and 100 trees retained), the all-zero ancestor, as well as Ichthyopterygia and turtles, were removed, and Captorhinidae and Araeoscelidia served as outgroups instead. Forty-seven MPTs were found with the shortest tree length of 520 (CI=0.358, RI=0.662, RC=0.237 and HI=0.642). Results were overall comparable to the outcome of the third run as indicated by the strict consensus (Supplementary Fig. S8), with relationships among Sauropterygia being slightly better resolved. Note that in this analysis, Cymatosaurus again moved onto the plesiosaur stem.

For the fifth analysis, the matrix was pruned to include only Sauropterygia as ingroup and Sinosaurosphargis as outgroup. Three MPTs were found with the shortest tree length of 315 (CI=0.483, RI=0.609, RC=0.294 and HI=0.517). Similar to the results of the first search run, a sistergroup relationship between Corosaurus and Cymatosaurus was recovered, but now this clade is sister to all remaining eosauropterygians. Ingroup relationships of the latter are not well resolved as indicated by polytomies in both the strict consensus (Supplementary Fig. S9a) and the 50% majority rule tree (Supplementary Fig. S9b).

Discussion

Palatodonta is clearly a juvenile specimen, owing to its small size (20.5 mm in length; see Supplementary Table S1 for a full list of measurements), relatively large orbit and lack of extensive bone fusion. Thus, its suitability for phylogenetic analysis was investigated using osteological comparisons with modern reptilian hatchlings and adults (turtles, non-varanoid squamate lizards and crocodylians). This lead us to the interpretation that, although overall proportions change during ontogeny and sutures might become obliterated with age, the suture patterns of this juvenile generally reflect the adult condition of the new species (see Bhullar et al.20). This is also supported by observations in pachypleurosaurs, which also do not change cranial bone configuration through ontogeny21,22,23.

Palatodonta shares with the basal-most placodont Paraplacodus the distinctly open L-shaped jugal, as well as a ventrally open lower temporal fossa and excavated cheek region. The former character also appears convergently in Claudiosaurus and in some pachypleurosaurs, whereas the latter is a plesiomorphic condition for sauropterygians in general. The loss of the lower temporal fossa and closure of the cheek region is secondarily developed only among the more highly nested placodonts (Placodus and cyamodontoids18,24), the fusion of nasals found in the new skull is present only in some Cyamodus spp. so far, whereas the condition remains debatable in Paraplacodus.

Palatodonta is not a juvenile of any known placodont because juvenile specimens of Paraplacodus (Paläontologisches Institut und Museum Universität Zürich (PIMUZ) T2805) and the armoured cyamodontoid Cyamodus (PIMUZ T2797) show that, despite being of similar size, crushing dentition is already fully formed very early during ontogeny (Supplementary Fig. S3). Previous research shows that it is tooth formula that changes through placodont ontogeny, not shape25.

Although Palatodonta shares several characters with Paraplacodus, the presence of pointed palatal teeth suggests that Palatodonta is a stem representative with a very different lifestyle and diet to crown group Placodontia. We hypothesize that the comb-like arrangement of blunt, peg-like premaxillary teeth in Palatodonta (Supplementary Fig. S2b) were used for sifting through soft sediments on the shallow ocean floor to root out small, soft prey items, whereas the more massive equivalent teeth in Paraplacodus and Placodus served to pluck hard-shelled prey from hardgrounds3.

The palatine dentition in Palatodonta represents an intermediate condition between the denticles/teeth of stem neodiapsids26, and the flattened, enlarged palatal crushing teeth seen in placodonts4 (Fig. 4, Supplementary Note 1). An evidence-based scenario for this morphological transformation of dentition can thus be formulated.

In many Permian diapsid reptiles, clusters of small denticles or teeth are present on the vomer, palatine and pterygoid bones (Fig. 4a), thus an odontogenic band (a place of residence of stem cells active in tooth formation27) acting as precursor to dental lamina formation (Richman and Handrigan28 and references therein) is assumed to be present in these ancient reptiles. In particular, the expression of Shh (Sonic hedgehog) and transcription factor Pitx2 (pituitary homeobox 2) as part of a gene network with others (for example, _Wnt_- and _Bmp_-related pathways), must have had a critical role in palatal tooth formation28,29. These conserved pathways and proteins are not only important, for example, in patterning the central nervous system, in limb bud formation and internal organogenesis30, but are also known to be active in tooth development from fish to mammals31.

Compared with their Permian ancestors, the palatine of Placodontiformes increased in length and size relative to the vomer and the pterygoid, forming most of the palate, with the dentition of Palatodonta consisting of single row of conical palatine teeth similar to those of the maxillary tooth row (Fig. 4b). As indicated by studies of modern snakes32, a rostral and caudal truncation of the developmental field or a suppression of growth factors by antagonistic morphogens28 could have been responsible for the suppression of palatal teeth in the vomeral and pterygoidal regions in that taxon (Fig. 4a).

The dental formula was further modified in crown group Placodontia to be suited to a durophagous diet by reducing the number of ankylosed thecodont teeth16 and allowing them to become larger and successively flattened (Fig. 4c), whereas at the same time, increasing the alveolar dimensions in the skull bones and the mandible. We can assume that the enamel (=dental) organ forming placodont teeth was enlarged and flattened in the more derived placodonts in comparison with modern reptiles28, probably filling most of the dental alveolar space, to generate the broad, sheet-like initial enamel secretion forming the top layer of the plate- or bean-shaped crushing teeth (including replacement teeth; Fig. 4). One means to achieve a size increase in teeth in mammals33 is the suppression of apoptosis during early development (that is, suppressing p21, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor), a mechanism associated with pathological macrodontia (anomalous enlargement of teeth). However, differences in apopotosis between reptile and mammal teeth are known, with apoptosis affecting the stellate reticulum in the former but occurring at the inner enamel epithelia in the latter28. A considerable increase in enamel organ dimension could then have caused a displacement of the successional dental lamina, so that tooth replacement became vertical (Fig. 4d) and not lingual to the functional tooth16.

Although there is a general consensus that Sauropterygia are well nested within Diapsida4,34, the exact relationships within and among groups are still debated. Our results indicate that pachypleurosaurs, together with nothosaurs, are highly nested within Sauropterygia (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. S4; Supplementary Notes 2 and 3). In contrast, it was previously widely accepted that the small- to medium-sized Pachypleurosauria represented the most plesiomorphic clade within Eosauropterygia, and palaeobiogeographic hypotheses favoured an origination of the whole group in the Eastern Tethyan realm11. This was supported, for example, by the occurrence of Keichousaurus yuananensis from the Jialingjiang Formation, Hubei Province, China, which is either late Early Triassic or early Middle Triassic in age4,35. New, yet to be described, sauropterygian material has recently been found in the Early Triassic (Spathian, Olenekian) of Chaohu, Anhui Province, however36. Given the fact that the geologically oldest eosauropterygians outside of Asia (Corosaurus from North America and Sauropterygia indet. from Europe4) also occur in the late Early Triassic, however, the western Tethys or the eastern Panthalassic ocean could potentially have been the site of origin for the clade as well (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. S4). Despite this, a robust node in all phylogenetic analyses conducted (see Supplementary Figs S5–S10) indicates that Placodontiformes originated in the Western Tethys, and from there diversified and migrated into the Eastern faunal province.

Methods

μCT scanning

Scanning was carried out with a Phoenix v tome x s (GE Phoenix X-ray; 240 kV) at the Steinmann Institute, University of Bonn, Germany, with a voltage of 170 kV and a current of 150 μA. A total of 1,501 images were taken without beam filtration, each with an exposure time of 667 ms, resulting in a voxel size of 0.055 mm. Stacks of digital CT images were produced with the VGStudio MAX 2.0 software (Volume Graphics) and served as the base for virtual three-dimensional reconstructions of the bony structures by means of the manual segmentation function of the software Avizo version 6.2.1.

Phylogenetic analysis

Analyses were run in PAUP 4.0b10 for Microsoft Windows 95/NT37 using PaupUP38 version 1.0.3.1. Trees resulting from the analyses were transformed using Mesquite[39](/articles/ncomms2633#ref-CR39 "Maddison, W. P. & Maddison, D. R. . Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 2.75, http://mesquiteproject.org

(2011) .") and the Adobe Photoshop Creative Suite. All analyses were run under parsimony setting using the heuristic search option, with all 140 characters being unordered and not weighted in any way. Furthermore, all characters were found to be parsimony-informative, no aspect of the tree topology was enforced and the ingroup was set to be monophyletic.The character matrix used herein is based on the matrix of Liu et al.11, which is itself based mainly on Rieppel et al.40 (in return this matrix was based on Rieppel41). The original characters (7) and (120) were removed by Liu et al.11 because they were found uninformative in their analysis, whereas two new characters (1) and (61) were added from Rieppel and Lin10. Note that the re-shuffling of characters by Liu et al.11, in contrast to the matrices used by Li et al.42, Shang et al.43 or Wu et al.44, is also adopted herein.

From the matrix used by Liu et al.11, several character definitions of the matrix were modified and three new characters (138–140) have been introduced. On the other hand, a few of the original taxa used have been re-scored (Cyamodus, Placodus, Wumengosaurus and Younginiformes). Instead of Younginiformes, Hovasaurus boulei45 (scoring followed mainly Currie46 and Bickelmann et al.47, as well as personal observation of specimens in the PIMUZ collections) and Youngina capensis48 (scoring followed Smith and Evans49 and Bickelmann et al.47) are used as terminal taxa, because the group was recently found to be paraphyletic47.

On the other hand, several sauropterygian taxa new to the Liu et al.11 matrix (Diandongosaurus acutidentatus, Paraplacodus broilii, Psephoderma alpinum; Yunguisaurus liae and Palatodonta; this paper), as well as thalattosaurs (scoring after Müller50,51,52, Müller et al.53, Liu and Rieppel54, Li et al.42 and personal observations of specimens in the PIMUZ collections), the stem turtle Odontochelys semitestacea55, Ichthyopterygia and four additional neodiapsid taxa (Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi, Sinosaurosphargis yunguiensis, Hanosaurus hupehensis and Helveticosaurus zollingeri) have been added. The new matrix thus comprises 42 taxa (43 for those that include a hypothetical all-zero ancestor) and 140 informative characters in total. For the present study, less well-known or highly fragmentary Chinese sauropterygian taxa such as Chinchenia, Kwangsisaurus, Sanchiaosaurus34,41,44 and Largocephalosaurus56 were not included.

Bootstrapping and Bremer support

A first bootstrap analysis (based on 1,000 replicates) was performed on the matrix used in the first search run. This analysis shows a loss of resolution in large parts of the tree. However, the newly proposed Placodontiformes has a value of 78% (Supplementary Fig. S10a), with a Bremer support score of 3 for the clade. A second bootstrap analysis (again based on 1,000 replicates) was run on the data set of the third run (Ichthyopterygia and turtles removed), which also showed high support (75%) for Placodontiformes, while Bremer support score for the taxon remained at 3 (Supplementary Fig. S10b). Apart from these slightly different bootstrap values, the general topologies of the two trees did not change, with the exception of the all-zero ancestor and Captorhinidae forming a basal polytomy in Supplementary Fig. S10a, instead of a resolved grade in Supplementary Fig. S10b. The third bootstrap analysis (Supplementary Fig. S10c; also with 1,000 replicates) was performed on the pruned data set of the fifth analysis (Supplementary Fig. S9a). Here the bootstrap support and topology was generally similar to the previous analyses, although support for Placodontiformes is much higher at 91%, and Wumengosaurus now forms a clade with the European pachypleurosaurs (Supplementary Fig. S10c). Once again, the node Placodontiformes had a Bremer support score of 3.

Nomenclatural acts

This published work and the nomenclatural act it contains have been registered in ZooBank, the proposed online registration system for the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). The ZooBank LSIDs (Life Science Identifiers) can be resolved and the associated information viewed through any standard web browser by appending the LSID to the prefix 'http://zoobank.org/'. The LSID for this publication is: urn:lsid:zoobank.org: pub:2CC51C4F-03F2-4647-9829-99646F6DA78E.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Neenan, J. M. et al. European origin of placodont marine reptiles and the evolution of crushing dentition in Placodontia. Nat. Commun. 4:1621 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2633 (2013).

Change history

01 October 2013

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

- Cheng, Y.-N., Wu, X.-C. & Ji, Q. . Triassic marine reptiles gave birth to live young. Nature 432, 383–386 (2004) .

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Motani, R. . The evolution of marine reptiles. Evol. Educ. Outreach 2, 224–235 (2009) .

Article Google Scholar - Scheyer, T. M. et al. Revised paleoecology of placodonts–with a comment on ‘The shallow marine placodont Cyamodus of the central European Germanic Basin: its evolution, paleobiogeography and paleoecology’ by C.G. Diedrich (Historical Biology, iFirst article, 2011, 1–19. doi:10.1080/08912963.2011.575938) Hist. Biol. 24, 257–267 (2012) .

Article Google Scholar - Rieppel, O. . Handbook of Paleoherpetology Vol 12A 1–134Verlag Dr Friedrich Pfeil: Munich, (2000) .

- O'Keefe, F. R. & Chiappe, L. M. . Viviparity and k-selected life history in a Mesozoic marine plesiosaur (Reptilia, Sauropterygia). Science 333, 870–873 (2011) .

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Motani, R. . Warm-blooded ‘sea dragons’? Science 328, 1361–1362 (2010) .

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Benson, R. B. J., Butler, R. J., Lindgren, J. & Smith, A. S. . Mesozoic marine tetrapod diversity: mass extinctions and temporal heterogeneity in geological megabiases affecting vertebrates. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 277, 829–834 (2010) .

Article Google Scholar - Rieppel, O. . Phylogeny and paleobiogeography of Triassic Sauropterygia: problems solved and unresolved. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 153, 1–15 (1999) .

Article Google Scholar - Rieppel, O. . Paraplacodus and the phylogeny of the Placodontia (Reptilia: Sauropterygia). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 130, 635–659 (2000) .

Article Google Scholar - Rieppel, O. & Lin, K. . Pachypleurosaurs (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Lower Muschelkalk, and a review of the Pachypleurosauroidea. Fieldiana, Geol. 32, 1–44 (1995) .

Google Scholar - Liu, J. et al. A new pachypleurosaur (reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Lower Middle Triassic of Southwestern China and the phylogenetic telationships of Chinese pachypleurosaurs. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 31, 292–302 (2011) .

Article Google Scholar - Kelley, N. P., Motani, R., Jiang, D.-Y., Rieppel, O. & Schmitz, L. . Selective extinction of Triassic marine reptiles during long-term sea-level changes illuminated by seawater strontium isotopes. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.07.026 (2012) .

- Agassiz, L. . Recherches sur les Poissons Fossiles Vol. I–V, Imprimaire de Petitpierre (1833–1845) .

- Hagdorn, H. & Simon, T. . Vossenveld formation. In LithoLex [Lithostratigraphisches Lexikon der Deutschen Stratigraphischen Kommission; online-database]. Hannover: BGR. Last updated 02.08.2010 [cited 4th March 2013], Record ID. 45. Available from: http://www.bgr.de/app/litholex/gesamt_ausgabe_neu.php?id=45 (2010) .

- Oosterink, H. W. & Winterswijk, Geologiedeel II . De Triasperiode (geologie, mineralen en fossielen). Wetenschappelijke Mededeling van de Koninklijke Nederlandse Natuurhistorische Vereniging 178, 1–120 (1986) .

Google Scholar - Rieppel, O. . Tooth implantation and replacement in Sauropterygia. Paläontol. Z 75, 207–217 (2001) .

Article Google Scholar - Neenan, J. M. & Scheyer, T. M. . The braincase and inner ear of Placodus gigas (Sauropterygia, Placodontia)—a new reconstruction based on micro-computed tomographic data. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 32, 1350–1357 (2012) .

Article Google Scholar - Rieppel, O. . The cranial anatomy of Placochelys placodonta Jaekel, 1902, and a review of the Cyamodontoidea (Reptilia, Placodonta). Fieldiana, Geol. 45, 1–104 (2001) .

Google Scholar - Gardner, N. M., Holliday, C. M. & O’Keefe, F. R. . The braincase of Youngina capensis (Reptilia, Diapsida): new insights from high-resolution CT scanning of the holotype. Palaeontologia Electronica 13, 19A (2010) .

Google Scholar - Bhullar, B.-A. S. et al. Birds have paedomorphic dinosaur skulls. Nature 487, 223–226 (2012) .

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Sander, P. . A fossil reptile embryo from the Middle Triassic of the Alps. Science 239, 780–783 (1988) .

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Sander, P. M. . The pachypleurosaurids (Reptilia: Nothosauria) from the Middle Triassic of Monte San Giorgio (Switzerland) with the description of a new species. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 325, 561–666 (1989) .

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Klein, N. . Skull morphology of Anarosaurus heterodontus (Reptilia: Sauropterygia: Pachypleurosauria) from the Lower Muschelkalk of the Germanic Basin (Winterswijk, The Netherlands). J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 29, 665–676 (2009) .

Article Google Scholar - Rieppel, O. . The genus Placodus: systematics, morphology, paleobiogeography, and paleobiology. Fieldiana, Geol. 31, 1–44 (1995) .

Google Scholar - Kuhn-Schnyder, E. . Über das Gebiss von. Cyamodus. Mitteilungen aus dem Paläontologischen Institut der Universität Zürich 1, 174–188 (1959) .

Google Scholar - Romer, A. S. . Osteology of the reptiles University of Chicago Press (1956) .

- Smith, M. M., Fraser, G. J. & Mitsiadis, T. A. . Dental lamina as source of odontogenic stem cells: evolutionary origins and developmental control of tooth generation in gnathostomes. J. Exp. Zool. 312, 260–280 (2009) .

Article Google Scholar - Richman, J. M. & Handrigan, G. R. . Reptilian tooth development. Genesis 49, 247–260 (2011) .

Article Google Scholar - Fraser, G. J. et al. An ancient gene network Is co-opted for teeth on old and new jaws. PLoS Biol. 7, e1000031doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000031 (2009) .

Article Google Scholar - Gilbert, S. F. . Developmental Biology 9th edn Sinauer Associates, Inc. (2010) .

- Fraser, G. J., Britz, R., Hall, A., Johanson, Z. & Smith, M. M. . Replacing the first-generation dentition in pufferfish with a unique beak. PNAS 109, 8179–8184 (2012) .

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Mahler, D. L. & Kearney, M. . The palatal dentition in squamate reptiles: morphology, development, attachment, and replacement. Fieldiana, Zool. 108, 1–61 (2006) .

Google Scholar - Kim, J.-Y. et al. Inhibition of apoptosis in early tooth development alters tooth shape and size. J. Dent. Res. 85, 530–535 (2006) .

Article Google Scholar - Rieppel, O. . The systematic status of Hanosaurus hupehensis (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) from the Triassic of China. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 18, 545–557 (1998) .

Article Google Scholar - Li, J.-L. . A brief summary of the Triassic marine reptiles of China. Vertebr. PalAsiat. 44, 99–108 (2006) .

Google Scholar - Jiang, D.-Y., Motani, R., Tintori, A., Rieppel, O. & Sun, Z.-Y. . Two new Early Triassic marine reptiles from Chaohu, Anhui Province, South China. J. Vertebr. Paleontol., SVP Program and Abstracts Book 117 (2012) .

- Swofford, D. L. . PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods). Version 4 (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts (2003) .

- Calendini, F. & Martin, J.-F. . PaupUP v1.0.3.1 A free graphical frontend for Paup* Dos software (2005) .

- Maddison, W. P. & Maddison, D. R. . Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 2.75, http://mesquiteproject.org (2011) .

- Rieppel, O., Sander, P. M. & Storrs, G. W. . The skull of the pistosaur Augustasaurus from the Middle Triassic of northwestern Nevada. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 22, 577–592 (2002) .

Article Google Scholar - Rieppel, O. . The sauropterygian genera Chinchenia, Kwangsisaurus, and Sanchiaosaurus from the Lower and Middle Triassic of China. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 19, 321–337 (1999) .

Article Google Scholar - Li, C., Rieppel, O., Wu, X.-C., Zhao, L.-J. & Wang, L.-T. . A new Triassic marine reptile from Southwestern China. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 31, 303–312 (2011) .

Article CAS Google Scholar - Shang, Q.-H., Wu, X.-C. & Li, C. . A new eosauropterygian from the Middle Triassic of eastern Yunnan Province, southwestern China. Vertebr. PalAsiat. 49, 155–171 (2011) .

Google Scholar - Wu, X.-C., Cheng, Y.-N., Li, C., Zhao, L.-J. & Sato, T. . New information on Wumengosaurus delicatomandibularis Jiang et al., 2008 (Diapsida: Sauropterygia), with a revision of the osteology and phylogeny of the taxon. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 31, 70–83 (2011) .

Article Google Scholar - Piveteau, J. . Paleontologie de Madagascar, XIII.—amphibiens et reptiles permiens. Ann. Paleontol. 15, 53–180 (1926) .

Google Scholar - Currie, P. J. . Hovasaurus boulei, an aquatic eosuchian from the Upper Permian of Madagascar. Palaeontol. Afr. 29, 99–168 (1981) .

Google Scholar - Bickelmann, C., Müller, J. & Reisz, R. R. . The enigmatic diapsid Acerosodontosaurus piveteaui (Reptilia: Neodiapsida) from the Upper Permian of Madagascar and the paraphyly of ‘younginiform’ reptiles. Can. J. Earth Sci. 46, 651–661 (2009) .

Article Google Scholar - Broom, R. . A new thecodont reptile. Proc. Zool. Soc. London Ser. B 84, 1072–1077 (1914) .

Google Scholar - Smith, R. M. H. & Evans, S. E. . An aggregation of juvenile Youngina from the Beaufort Group, Karoo Basin, South Africa. Palaeontol. Afr. 32, 45–49 (1995) .

Google Scholar - Müller, J. . In Recent Advances in the Origin and Early Radiation of Vertebrates (eds. Arratia, G., Wilson, M. V. H. & Cloutier, R.) 379–408Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil (2004) .

- Müller, J. . The anatomy of Askeptosaurus italicus from the Middle Triassic of Monte San Giorgio and the interrelationships of thalattosaurs (Reptilia, Diapsida). Can. J. Earth Sci. 42, 1347–1367 (2005) .

Article ADS Google Scholar - Müller, J. . First record of a thalattosaur from the Upper Triassic of Austria. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 27, 236–240 (2007) .

Article Google Scholar - Müller, J., Renesto, S. & Evans, S. E. . The marine diapsid reptile Endennasaurus from the Upper Triassic of Italy. Palaeontology 48, 15–30 (2005) .

Article Google Scholar - Liu, J. & Rieppel, O. . Restudy of Anshunsaurus huangguoshuensis (Reptilia: Thalattosauria) from the Middle Triassic of Guizhou, China. Am. Mus. Novit. 3488, 1–34 (2005) .

Article Google Scholar - Li, C., Wu, X.-C., Rieppel, O., Wang, L.-T. & Zhao, L.-J. . An ancestral turtle from the Late Triassic of southwestern China. Nature 456, 497–501 (2008) .

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Cheng, L., Chen, X., Zeng, X. & Cai, Y. . A new eosauropterygian (Diapsida: Sauropterygia) from the Middle Triassic of Luoping, Yunnan Province. J. Earth Sci. 23, 33–40 (2012) .

Article CAS Google Scholar - Blakey, R. . Global Paleogeography Maps, Library of Paleogeography, Colorado Plateau Geosystems Inc. Website. http://cpgeosystems.com/paleomaps.html (2012). [cited 4th March 2013] http://www2.nau.edu/rcb7/ (2012) .

- McKie, T. & Williams, B. . Triassic palaeogeography and fluvial dispersal across the northwest European Basins. Geol. J. 44, 711–741 (2009) .

Article Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the Sibelco Europe MineralsPlus Winterswijk company and to R. Bleeker, who found the fossil and donated it to the TwentseWelle Museum so that we were able to describe it in the present paper. We thank O. Dülfer (SIPB) for preparation of the specimen, G. Oleschinski (SIPB) for photography and D. Kranz (SIPB) for providing the artwork for Supplementary Fig. S1. We also thank B. Scheffold (PIMUZ), who contributed artwork to Fig. 3, Marcelo Sánchez and the other members of PIMUZ for discussion and input, and whose assistance greatly improved the manuscript. This work was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 31003A 127053) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Palaeontological Institute and Museum, University of Zurich, Karl Schmid-Strasse 4, Zurich, CH-8006, Switzerland

James M. Neenan & Torsten M. Scheyer - Steinmann Institute for Geology, Mineralogy and Palaeontology, University of Bonn, Nussallee 8, Bonn, 53115, Germany

Nicole Klein

Authors

- James M. Neenan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Nicole Klein

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Torsten M. Scheyer

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

J.M.N. and T.M.S. wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures. N.K. and J.M.N. conducted the morphological description of outwardly visible structures. N.K. carried out the CT scanning. T.M.S. and J.M.N. performed the phylogenetic analysis. J.M.N. created the three-dimensional reconstruction and conducted the morphological description of the concealed elements.

Corresponding author

Correspondence toTorsten M. Scheyer.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S10, Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Note 1 - 3, and Supplementary References (PDF 1133 kb)

Supplementary Movie 1

A 360° rotation view of the blunt-snouted skull. (MOV 20713 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neenan, J., Klein, N. & Scheyer, T. European origin of placodont marine reptiles and the evolution of crushing dentition in Placodontia.Nat Commun 4, 1621 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2633

- Received: 08 August 2012

- Accepted: 21 February 2013

- Published: 27 March 2013

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2633