Setting a trap for tissue fibrosis (original) (raw)

The accumulation of fibroblasts in epithelial organs such as the kidney can produce dangerous scars. Such tissue fibrosis begins when epithelial cells morph into fibroblasts by epithelial-mesenchymal transition. A key regulator of this process in the kidney now emerges (pages 387–393).

Chronic inflammation leads to the buildup of scar tissue containing new fibroblasts and excess collagen. In epithelial organs like lung, liver and kidney, tissue fibrosis cripples function and signals progressive disease. New fibroblasts typically appear in proximity to epithelial units that are coming apart. One explanation is that tissue fibroblasts derive from epithelial cells in a process dubbed epithelial-mesenchymal transition1.

Most epithelia line organ tubules or ducts. When injured, epithelia either fall into the lumen and die, or transition to fibroblasts. Surviving fibroblasts crawl back into adjacent interstitial spaces to lay down unwanted collagen as scar tissue. Although this concept challenges the traditional notion of terminal differentiation, it is clear that some epithelia can reinvent themselves2. Such events are well shown in the kidney but likely also occur elsewhere.

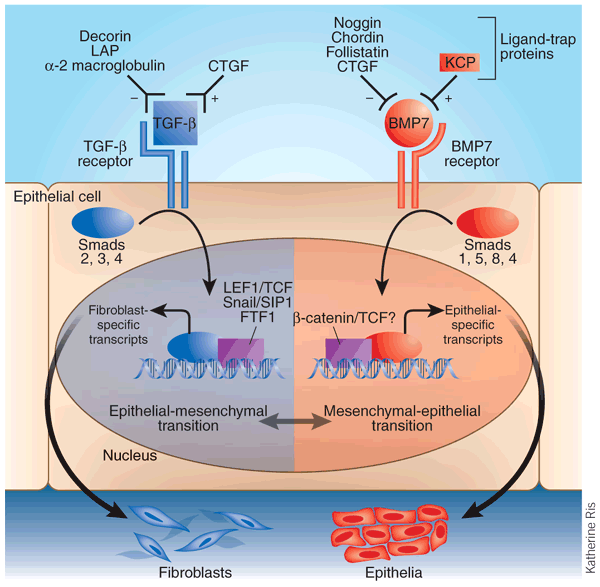

In this issue, Lin et al.3 identify a kielin/chordin-like protein (KCP) that negatively regulates kidney fibrosis. The authors show that KCP operates by facilitating the action of another cytokine previously found to protect against fibrosis, the signaling ligand bone morphogenic protein 7 (BMP7). For the moment, the best explanation for the effect of KCP is that it acts as a 'ligand-trap protein' to enhance binding of BMP7 to its receptor. KCP thereby antagonizes epithelial-mesenchymaltransition (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Overview of a epithelial-mesenchymal transition controlled by TGF-β and BMP7.

Katherine Ris

Free TGF-β or BMP7 is bidirectionally modulated in its receptor binding by positive or negative ligand-trap proteins in the extracellular milieu. Activation of the TGF-β receptor on an epithelial cell induces the phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 and its nuclear import with Smad4. In the nucleus, these Smad proteins operate in concert with various transcription factors to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition and repress mesenchymal-epithelial transition. For instance, fibroblast genes like those encoding fibroblast-specific protein-1 and collagen are upregulated and epithelial-specific genes are downregulated. Activation of the BMP7 receptor induces the phosphorylation of Smad1, Smad5 and Smad8, which in the nucleus engages mesenchymal-epithelial transition, and opposes epithelial-mesenchyme transition. TGF-β signaling encourages the formation of fibroblasts—and scar tissue—through epithelial-mesenchyme transition. BMP7 action tends to preserve the epithelial phenotype. Ligand-trap proteins, including KCP, can modulate this whole process, as suggested by Lin et al.3

The molecular underpinnings of epithelial-mesenchymal transition with respect to fibrosis are starting to emerge. Importune cytokine activity and disruption of underlying basement membrane by local proteases initiate the transition in at-risk epithelia. Among the classic modulators of this process are members of the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β superfamily2, which comprises the TGF-β/activin and BMP/GDF subfamilies4. Each subfamily uses a distinctive set of receptors and a different complement of Smad signaling proteins.

TGF-β signaling tends to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition2. TGF-β activation of its receptor phosphorylates Smad2 and Smad3, which are then imported into the nucleus with Smad44. Nuclear Smads modulate gene activity as cofactors with other transcriptional proteins, such as lymphoid enhancer factor-1/T-cell factor (LEF1/TCF). In line with this molecular scheme, impairment of Smad3 signaling inhibits renal fibrogenesis5 and shuttling of LEF1/TCF into the nucleus by β-catenin is crucial for epithelial-mesenchymal transition6. Transitioning epithelia morph into fibroblasts by rearranging their actin stress fibers and expressing new proteins such as fibroblast-specific protein-1, matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9, and interstitial collagens2.

BMP7 signaling seems to counteract epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promote just the opposite, mesenchymal-epithelial transition. Experiments in mature renal tissue show that BMP7 signaling antagonizes epithelial-mesenchymal transition driven by TGF-β7. Moreover, BMP7 stabilizes differentiation and branching during development of renal tubules8. In several models of kidney injury, the administration of BMP7 in pharmacological doses attenuates the process of renal fibrosis and in some cases restores the structure of epithelial tubules7,9,10.

Although TGF-β and BMP7 signaling create a balanced paradigm, other signaling pathways and transcription factors undoubtedly come in play2. Nevertheless, the reciprocity between these two cytokines provides a useful framework for building more complex models of epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

Another emerging feature of epithelial-mesenchymal transition is the potential role of ligand-trap proteins in the regulation of epithelial transitions leading to fibrosis (Fig. 1). Trap proteins are attached to cell membranes and act as accessory coreceptors, or circulate in interstitial spaces as soluble moieties to block receptor activation by free ligand4. They are increasingly understood as important modulators of body plan development during embryogenesis11. Whereas TGF-β and the BMPs share some soluble trap proteins, most ligand-trap proteins have subfamily specificity; within a subfamily, however, there is promiscuity.

Many trap proteins are negative regulators of receptor binding. The TGF-β trap protein decorin, for instance, prevents renal fibrosis after inflammation of renal glomeruli12. Negative trap proteins for TGF-β also include LAP and α2-macroglobulin, and for BMP7 include noggin, chordin and follistatin4,11. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) is both a positive trap that facilitates the binding of TGF-β to its receptor and a negative trap for BMP7 (ref. 13). There have been no reports until now of trap proteins that facilitate receptor binding to BMP7. Enter KCP.

KCP is a secreted protein containing multiple cysteine-rich signaling domains14. Lin et al. found that KCP enhanced receptor binding of BMP7 (and BMP4) and elevated intracellular levels of phosphorylated Smad1 (ref. 3). Whether there is an effect on Smad2 and Smad3 mediating TGF-β was not addressed in the current study.

Lin et al.3 showed that KCP-null mice were born normal and matured as adults without incident until they were stressed. The authors next challenged the mice by inducing acute tubular necrosis along their kidney tubules and found that the mice developed a renal fibrosis not seen in wild-type controls.

In a second model, after obstruction of one kidney, the scarring in that kidney was more intense than in wild-type controls and occurred earlier. Unexpectedly, in these experiments fibrosis also appeared in the contralateral, erstwhile normal, kidney. This was probably the result of profibrotic cytokines leaking from the obstructed kidney that re-entered the circulation—although no one knows for sure. An implication of this result is that KCP might normally rescue local epithelia under collateral assault by drivers of epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

Lin et al.3 also showed that KCP is expressed in embryonic tissues, but not routinely in the adult. Curiously, embryos do not form scars when wounded15. Perhaps the embryonic expression of KCP or other trap proteins partly explains this observation. In adult injury, KCP is probably expressed in response to stress.

There are no effective treatments for established tissue fibrosis, which has led to an emphasis on understanding the molecular processes behind it. The study of Lin et al.3 offers up a more sophisticated view of the role of cytokine balance in epithelial-mesenchymal transition that results in scarification. Regulation at two levels of competition can now be imagined; one level depends on the extracellular equilibrium of rival ligand-trap proteins, whereas the second level operates intracellularly by modulating the balance of various Smad proteins in the nucleus. This dual control favors a state of terminal differentiation in normal epithelia that preserves organ structure and function.

BMP7 has shown promise as an avenue of therapy in mouse models of fibrosis, although human clinical studies have yet to get underway. If KCP can be produced recombinantly, it may serve a combined role with BMP7 in attenuating new like tissue scars therapeutically.

References

- Iwano, M. et al. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 341–350 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kalluri, R. & Neilson, E.G. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1776–1784 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lin, J. et al. Nat. Med. 11, 387–393 (2005).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Shi, Y. & Massague, J. Cell 113, 685–700 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Sato, M., Muragaki, Y., Saika, S., Roberts, A.B. & Ooshima, A. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1486–1494 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kim, K., Lu, Z. & Hay, E.D. Cell. Biol. Int. 26, 463–476 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zeisberg, M. et al. Nat. Med. 9, 964–968 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zeisberg, M. & Kalluri, R. J. Mol. Med. 82, 175–181 (2004).

Article Google Scholar - Wang, S. et al. Kidney Int. 63, 2037–2049 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Morrissey, J. et al. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13 (Suppl. 1), S14–S21 (2002).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Balemans, W. & Van Hul, W. Dev. Biol. 250, 231–250 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Border, W.A. et al. Nature 360, 361–364 (1992).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Abreu, J.G., Ketpura, N.I., Reversade, B. & De Robertis, E.M. Nat. Cell. Biol. 4, 599–604 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Garcia Abreu, J., Coffinier, C., Larrain, J., Oelgeschlager, M. & De Robertis, E.M. Gene 287, 39–47 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Bullard, K.M., Longaker, M.T. & Lorenz, H.P. World J. Surg. 27, 54–61 (2003).

Article Google Scholar

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Departments of Medicine and Cell and Developmental Biology, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, 37232, Tennessee, USA

Eric G Neilson

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neilson, E. Setting a trap for tissue fibrosis.Nat Med 11, 373–374 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/nm0405-373

- Issue date: 01 April 2005

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nm0405-373