Gut bacteria and the host synergies promote resveratrol metabolism and induce tolerance in ALD mice (original) (raw)

Introduction

Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) is one of the most common chronic diseases, accounting for 48% of cirrhosis-related deaths1. During the current COVID-19 pandemic alone, alcohol-related liver mortality has increased by ~20%2. In Asian countries, the burden of alcohol-related diseases is rapidly increasing3. Additionally, alcohol consumption imposes significant economic burdens on families3. Current treatments for ALD are limited and mainly involve abstinence, nutritional support, drug therapy, and in severe cases, liver transplantation4. For ALD patients unwilling or unable to abstain from alcohol, stable and safe treatment strategies are needed to mitigate disease progression. Research indicates that flavonoids and resveratrol (RSV), among other natural compounds, can inhibit the progression of ALD5.

Resveratrol (RSV) is a widely studied natural compound with diverse effects6,7. Current data on the role of RSV in the development and progression of ALD in humans are limited. However, several compelling characteristics of RSV, coupled with the pressing clinical needs, have attracted significant attention from researchers regarding its potential in ALD drug development. Firstly, RSV is a natural polyphenolic compound with well-documented antioxidant7, anti-inflammatory8, and metabolic regulatory properties9,10. It exerts therapeutic effects by reducing lipid accumulation, hepatocyte necrosis, and liver fibrosis through its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms10. These biological effects confer on RSV the theoretical potential to ameliorate the pathological processes of ALD. Specifically, RSV has been shown to regulate lipid metabolism, suppress inflammatory responses, and delay cellular aging through pathways such as the activation of SIRT19. Given the close alignment of these mechanisms with the pathophysiology of ALD, RSV may hold substantial therapeutic potential for this condition. Secondly, extensive studies in animal models have demonstrated that RSV exerts protective effects against various liver diseases. For example, Resveratrol activates AMPK, inhibits mTOR, and thereby induces autophagy, helping to clear damaged cellular organelles and lipid droplets11. Resveratrol suppresses the NF-κB signaling pathway, thereby decreasing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and mitigating inflammatory responses10. These findings underscore RSV’s broad-spectrum hepatoprotective properties and further support its potential application in the treatment of ALD. Moreover, the clinical management of ALD is severely constrained by the lack of effective treatment options, with no therapies currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This unmet clinical need underscores the urgency of exploring new therapeutic targets and agents. RSV, with its favorable safety profile and demonstrated efficacy in treating other diseases, emerges as a promising candidate for ALD therapy, providing a solid foundation for further investigation. Lastly, the pathogenesis of ALD is multifactorial, involving gut microbiota, host metabolism, and inflammatory responses, among other factors12. RSV’s ability to modulate gut bacteria and host metabolism positions it as an ideal tool for exploring the complex pathophysiological mechanisms underlying ALD. By elucidating these mechanisms, RSV could offer valuable insights into the development of more effective treatment strategies. Therefore, although direct evidence regarding RSV’s therapeutic impact on ALD remains limited, its unique biological properties, positive results from animal models, and the urgent clinical demand collectively highlight its potential as an ideal drug candidate for ALD research. As such, RSV warrants further investigation to unlock its therapeutic potential in addressing this significant clinical challenge.

After a thorough analysis and review of previous studies, we have uncovered an intriguing phenomenon. While the therapeutic effects of RSV in rodent models of ALD are clearly demonstrable, no significant differences in efficacy are observed across effective dose gradients during long-term treatment11,13. For example, studies have shown that long-term use of RSV at low concentrations does not significantly affect the treatment of ALD in mice, while moderate and high doses show noticeable efficacy. However, there is no significant difference in efficacy observed between moderate and high doses11. There’ a study in mice also found that long-term administration of RSV at doses of 200 mg/kg/day and 400 mg/kg/day significantly improves the pathological condition of ALD, but there is also no significant difference in efficacy between these two dose groups of RSV13. These studies did not further investigate the reasons for the imbalance in the dose-response relationship of RSV11.

We all know that the concentration level of the drug in the body is key to determining the efficacy of RSV, so factors that cause changes in pharmacokinetics (PK) during long-term use of RSV may be the cause of the imbalance in the dose-response relationship. From the perspective of factors influencing RSV PK, both gut bacteria and host factors are involved in this process14,15. Gut bacteria metabolize RSV into dihydroresveratrol (DHR)14. In host intestinal epithelial cells and liver, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1) and sulfotransferase 1A1 (SULT1A1) respectively metabolize RSV into trans-resveratrol-3-O-β-D-glucuronide (R3G) and trans-resveratrol-3-sulfate sodium salt (R3S)15. ALD itself can significantly influence host factors and alter the composition of gut bacteria16, indicating its potential influence on the long-term PK of RSV during treatment. This may help us identify pathways leading to the imbalance in the dose-response relationship of RSV during long-term therapy.

Out of curiosity about this issue, we observed in a previous study of long-term treatment of RSV in ALD mice that the initial treatment of RSV was effective, but that long-term treatment could also be tolerated. Comparing similarly to the previous study, we observed that this phenomenon in long-term treatment may be related to pharmacokinetic changes, but the primary causative factors remain unresolved. Therefore, this study aims to elucidate, from the perspective of how gut bacteria and host factors affect long-term RSV PK, the reasons behind the imbalance in the dose-response relationship and even the occurrence of tolerance during long-term RSV treatment of ALD, providing scientific insights for the effectiveness of long-term therapeutic interventions.

Results

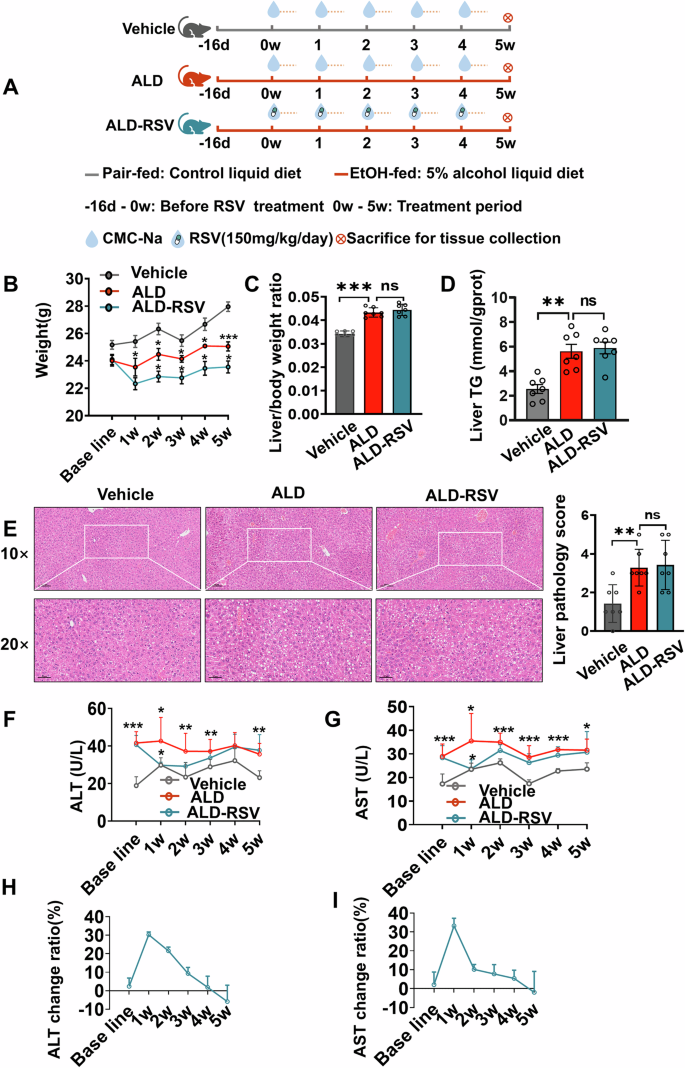

RSV tolerance appeared in long-term treatment ALD mice

The ALD mouse model was successfully established and maintained throughout the experimental period (Fig. 1). Physically, the weight of mice in the ALD group was lower than that of the Vehicle group (Fig. 1B). Pathologically, compared with the Vehicle group, H&E staining indicated that the ALD group showed marked hepatic steatosis with cytoplasmic vacuoles of varying sizes, occasional necrotic foci around the hepatic veins, fragmented and lysed nuclei, and a small number of granulocyte aggregates (Fig. 1E). Liver pathology score (Fig. 1E) and the liver to body weight ratio (Fig. 1C) were significantly increased by 130.00% (p = 0.0042) and 26.70% (p < 0.001). The TG content of the livers of ALD mice was also significantly elevated by 135.15% (p = 0.0005) compared to the Vehicle group (Fig. 1D). Serum biochemical analysis revealed significantly elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in ALD mice compared to the Vehicle group. In terms of dynamic monitoring, from baseline week to week 5, ALT levels increased by 120.36% (p < 0.001), 42.93% (p = 0.017), 58.75% (p = 0.005), 28.45% (p = 0.005), 24.88% (p = 0.068) and 54.04% (p = 0.003), respectively. AST levels rise 67.33% (p = 0.001), 50.95% (p = 0.012), 33.60% (p < 0.001), 64.00% (p < 0.001), 39.77% (p < 0.001), and 34.06% (p = 0.038), respectively (Fig. 1F, G). ALD modeling in mice prior to RSV treatment was successful (Supplementary Fig. 1). Liver inflammation and fibrosis indicators were also significantly elevated in the ALD group (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Collectively, these results demonstrate the successful establishment of the ALD mouse model.

Fig. 1: The therapeutic effect of long-term treatment with RSV on ALD mice was weakened.

A Experimental design diagram of long-term efficacy observation of RSV in ALD mice; B Long-term treatment with RSV reduced the body weight of ALD mice; C–E RSV has a decreased ability to ameliorate tissue damage in the liver based on pathology scores on liver sections and liver to body weight ratios. F, G Monitoring the influence of long-term treatment with RSV on ALT and AST levels in ALD mice; H, I When RSV was administered for long-term treatment in ALD mice, it was observed that the efficacy of RSV in reducing ALT and AST levels diminished. Intergroup differences were evaluated with unpaired Student’s t tests (two groups) or one-way ANOVA (three groups). Vehicle pair-fed control group, ALD alcohol-related liver disease, ALD-RSV Resveratrol-treated ALD group, RSV Resveratrol, PK pharmacokinetics, TG Triglyceride, ALT Alanine Aminotransferase, AST Aspartate Aminotransferase. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Significant differences between the indicated groups: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns no significance. The black hollow circles in the figures represent data points of different groups.

RSV is effective in the treatment of ALD, but the efficacy gradually decreases until tolerance is developed. Biochemical indicators showed that ALT and AST levels in the ALD-RSV group were reduced compared with those in the ALD group (Fig. 1F, G, Supplementary Table 1), indicating that RSV was effective. While in terms of dynamic monitoring, from week 1 to week 5. The ability of RSV to reduce ALT was 30.29% (p = 0.013), 21.54% (p = 0.097), 9.32%, 1.85% and −5.83%, respectively (Fig. 1H). The ability of RSV to reduce AST was 33.20% (p = 0.013), 10.12% (p = 0.054), 7.76%, 7.45%, and 2.83%, respectively (Fig. 1I). Physically, RSV further aggravated the weight loss of ALD mice (Fig. 1B). Pathologically, H&E staining showed that there was no significant remission in the ALD-RSV group compared with the ALD group (Fig. 1E), and there was no significant difference in the liver pathology scores (Fig. 1E) and liver to body weight ratio in the ALD-RSV group (Fig. 1C). There was also no significant reduction in liver TG levels in the ALD-RSV group (Fig. 1D). Mouse liver inflammation and fibrosis indices were also not significantly improved in the ALD-RSV group (Supplementary Fig. 2A). These results suggest that the efficacy of RSV in the treatment of ALD is diminishing, and even tolerance is emerging.

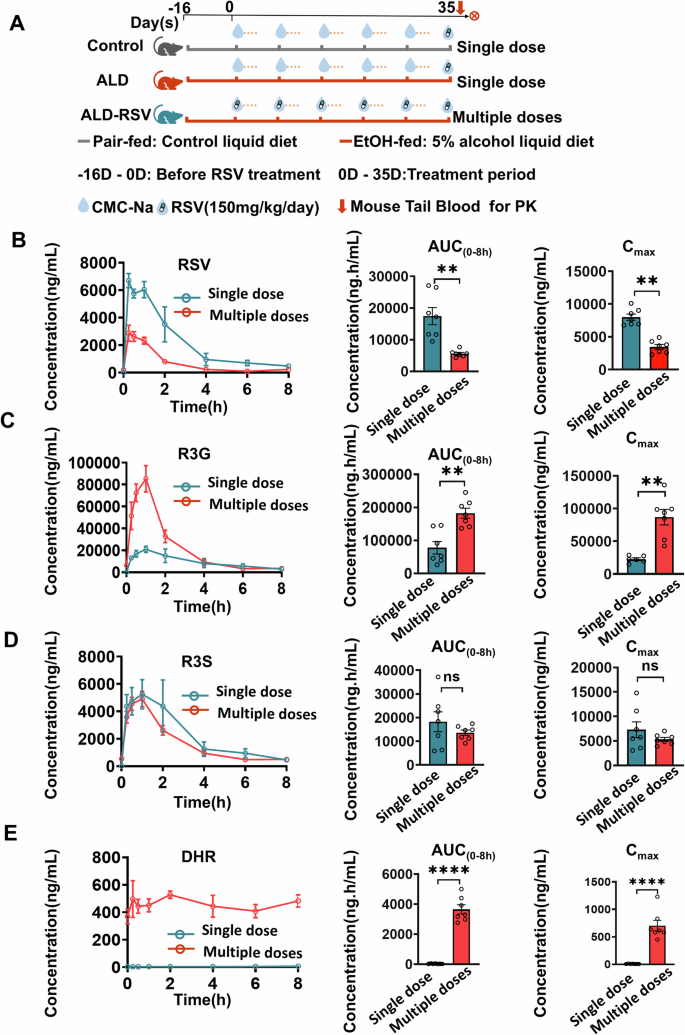

RSV exposure was reduced after long-term treatment in ALD Mice

The amount of exposure to RSV in the body is a decisive factor affecting its efficacy, so we examined the change of exposure to RSV under long-term use (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2). No significant changes in RSV exposure occurred in normal control mice and ALD mice by single gavage of RSV. (Supplementary Fig. 3). AUC(0-8h) of RSV was significantly reduced by 63.40% in the Multiple doses group compared with Single dose administration (p = 0.001) (Fig. 2B). As the main metabolite of RSV, the AUC(0-8h) and Cmax of R3G were significantly increased by 193.33% (p < 0.001) and 206.45% (p < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 2C). The AUC(0-8h) and Cmax of R3S, another major metabolite of RSV, did not change significantly (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, the gut bacterial metabolite DHR was observed after multiple dosing (Fig. 2E), but not detected at single dosing, suggesting that alterations in gut bacteria may affect RSV exposure during long-term therapy.

Fig. 2: The exposure of RSV was reduced after long-term (multiple doses) treatment in ALD mice.

A Experimental design diagram comparing the pharmacokinetics of RSV in mice following short-term (Single dose) and long-term (Multiple doses) administration. B–E Compared to single-dose administration, multiple doses of RSV result in a significant decrease in RSV self-exposure, while the production of the primary metabolite R3G significantly increases. However, there is no significant change in the production of another primary metabolite, R3S. DHR, a product of gut bacterial metabolism of RSV, was not detected upon short-term administration of RSV but was detectable following long-term administration. PK pharmacokinetics, Control pair-fed control group, ALD alcohol-related liver disease, ALD-RSV Resveratrol-treated ALD group, CMC-Na Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose, RSV resveratrol, R3G trans-resveratrol-3-O-β-D-glucuronide, R3S trans-resveratrol-3-sulfate sodium salt, DHR dihydroresveratrol, AUC(0-8h) area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 8 h, Cmax Peak plasma concentration. Intergroup differences were assessed using unpaired Student's _t_-tests. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 7). Significant differences between the indicated groups: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns no significance. The black hollow circles in the figures represent data points of different groups.

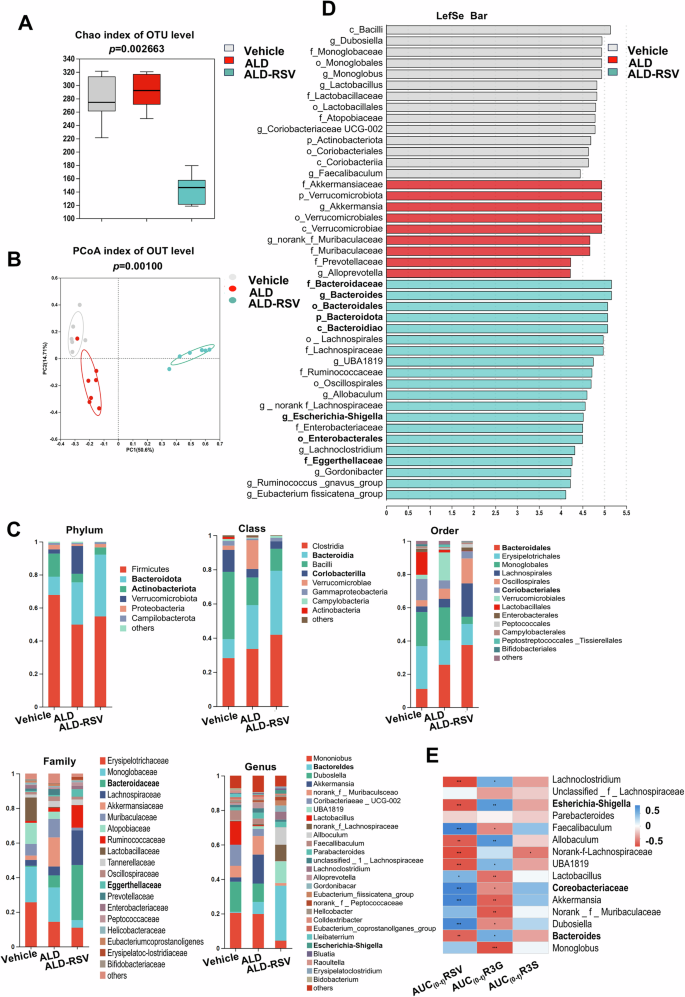

RSV and its metabolites exposure were influenced by gut bacteria in ALD mice

Gut bacteria, colloquially known as the “second liver,” have become a key factor affecting drug exposure. Gut bacteria metabolite DHR detected at multiple doses suggests that alterations in gut bacteria may affect RSV exposure during long-term treatment. As shown in Fig. 3A, the Chao indices, which reflect the abundance of bacterial species, decreased significantly in the ALD-RSV group after long-term administration, suggesting that the richness and diversity of gut bacteria decline after long-term administration. As shown in Fig. 3B, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on the Bray–Curtis algorithm revealed significant differences in the gut bacteria profiles among the three groups (p = 0.001). The most pronounced difference was observed in the ALD-RSV group, suggesting that RSV significantly altered the gut bacteria profiles in ALD mice. To further elucidate the differences in the gut bacteria of the three groups of mice, the sequences were compared using the RDP classifier and the changes in the gut bacteria at different levels of classification were compared. Community composition analysis showed that RSV could alter the composition of the mouse gut bacteria (Fig. 3C). LEfSe software was used to analyze the differences in bacterial communities among Vehicle, ALD and ALD-RSV mice at different taxonomic levels, and significant differences were observed in bacterial communities among the three groups (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3: Long term use of RSV in ALD mice can alter the profile of gut bacteria, which is related to RSV and exposure level.

A Compared with ALD mice, long-term administration of RSV significantly reduced the Chao alpha diversity index of the gut bacteria in ALD mice. B Based on the Bray–Curtis PCoA score plot, it is evident that the gut bacteria OTUs of ALD mice significantly separate from the ALD mouse model group and the sham-operated control mouse group after long-term administration of RSV. C Differences in gut bacterial composition at the level of phylum, order, order, family, and genus were observed after long-term administration of RSV. D Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) scores were obtained from LEfSe analysis, showing the biomarker taxa (LDA score > 4 and a significance of P < 0.05 determined by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test). E The exposure levels of RSV and R3G are positively correlated with the abundance of bacteria involved in their metabolism. Vehicle pair-fed control group, ALD alcohol-related liver disease, ALD-RSV Resveratrol-treated ALD group, OTU Operational Taxonomic Unit, RSV resveratrol, R3G trans-resveratrol-3-O-β-D-glucuronide, R3S trans-resveratrol-3-sulfate sodium salt, AUC(0-t) Area under the drug-time curve from 0 to t hour. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

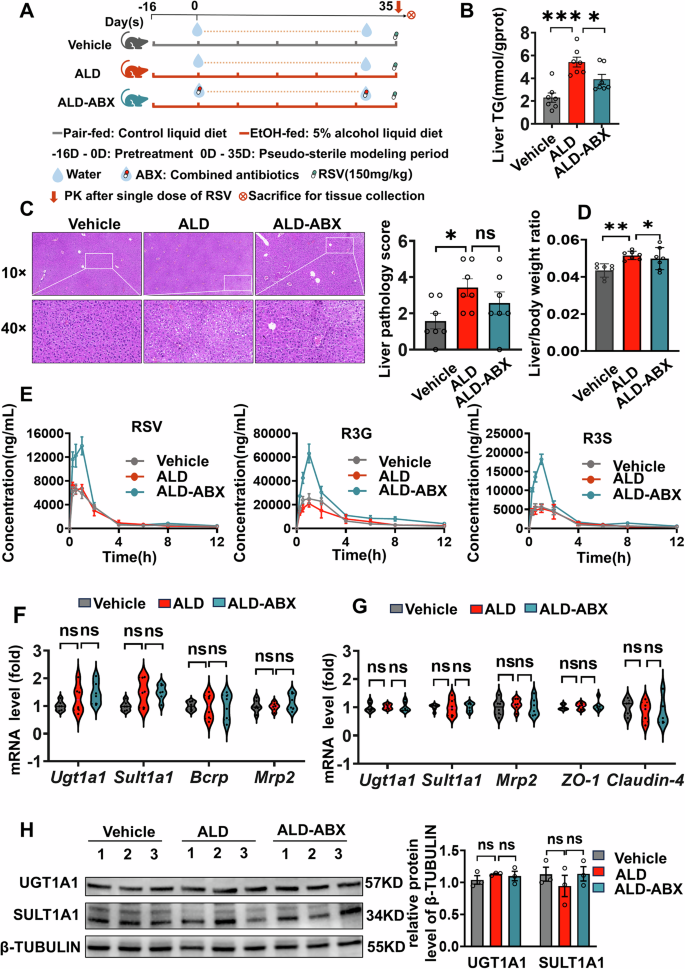

We designed experiments to continue investigating whether gut bacteria influence RSV exposure in ALD mice (Fig. 4A). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4B, after antibiotic treatment of mice, the concentration of gut bacterial DNA in ALD-ABX group was significantly reduced by 85.6% (p = 0.0015), confirming that most of the gut bacteria had been knocked down. ALD-ABX operation alleviates liver function in mice. There were no significant differences in liver pathological injury and liver weight ratio between the ALD and ALD-ABX groups (Fig. 4C, D). However, compared to the ALD group, the TG content of the liver was significantly reduced by 27.85% (p = 0.0391) in the ALD-ABX group. Antibiotic treatment also significantly alleviated inflammation and fibrosis in the mouse liver (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Antibiotic treatment of ALD mice did not significantly reduce CYP2E1 protein expression (Supplementary Fig. 4C). Exposure to RSV (parent drug) and its major metabolites was significantly increased in ALD-ABX mice compared to ALD mice (Fig. 4E, Supplementary Table 3). The AUC(0-12h) and Cmax of RSV were significantly elevated by 51.4% (p = 0.041) and 60.2% (p = 0.0051), respectively. Meanwhile, The AUC(0-12h) and Cmax of R3G were significantly increased by 126.70% (p = 0.0015) and 158.80% (p < 0.001), respectively. Similarly, the AUC(0-12h) and Cmax of R3S were significantly elevated by 118.20% (p = 0.0001) and 138.70% (p < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 4E, Supplementary Table 3). However, the PK of RSV and its metabolites did not show statistically significant differences between the Vehicle and ALD groups. The difference in these results may be due to the elimination of RSV-metabolizing bacteria in the ALD-ABX group, while the ALD group remained.

Fig. 4: The gut bacteria is another important factor, independent of host-related factors, influencing the exposure and metabolite generation of RSV during long-term administration in ALD mice.

A Experimental design diagram for studying whether the gut bacteria affect the exposure and metabolite generation of RSV in ALD mice. B After antibiotic treatment, the liver TG content in ALD mice was significantly reduced. C, D From the H&E staining and liver histopathological scoring, as well as the liver-to-body weight ratio, there were no significant changes observed in liver damage in ALD mice after combined antibiotics treatment. E ALD itself has no significant impact on the exposure level and metabolite generation of RSV. However, compared to the ALD group, the exposure level and metabolite generation of RSV in ALD-ABX mice group significantly increased after ABX-induced reduction of gut bacteria expression. F The major RSV metabolic enzymes Sult1a1 and Ugt1a1 and the drug transporters Bcrp and Mrp2 were not significantly changed at the mRNA level in the livers of ALD-ABX mice compared with the ALD group. G The mRNA levels of the major RSV-metabolizing enzymes Sult1a1 and Ugt1a1, the drug transporter Mrp2, and the intestinal permeability indicator _ZO-1_and Claudin-4 did not change significantly in the ileum of ALD-ABX mice compared with the ALD group. H Western blotting results showed that the expression of UGT1A1 and SULT1A1 in the livers of mice in the ALD-ABX group did not change significantly at the protein level compared with those of ALD mice. TG Triglyceride, PK pharmacokinetics, RSV resveratrol, R3G trans-resveratrol-3-O-β-D-glucuronide, R3S trans-resveratrol-3-sulfate sodium salt, ABX combined antibiotics, Vehicle pair-fed control group, ALD Alcohol-related liver disease, ALD-ABX Combined antibiotic treatment ALD group, Ugt1a1 UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1, Sult1a1 sulfotransferase 1A1, Bcrp Breast cancer resistance protein, Mrp2 Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 2, ZO-1 Zonula Occludens-1. A one-way ANOVA was used to compare the differences between the three groups. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Significant differences between the indicated groups: *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001; ns no significance. The black hollow circles in the figures represent data points of different groups.

For host influencing factors, RSV is mainly transported and excreted by MRP2 and BCRP, and is metabolized to R3G and R3S by the two-phase metabolic enzymes SULT1A1 and UGT1A1, respectively. There were no significant changes in the gene and protein levels of these major metabolizing enzymes and transporters in the livers of the Vehicle group, the ALD group and the ALD-ABX group (Fig. 4F, G). Thus, host influencing factors related to RSV metabolism in ALD mice did not change significantly after antibiotic administration, and the difference in RSV and its metabolite exposure were mainly attributed to changes in gut bacteria.

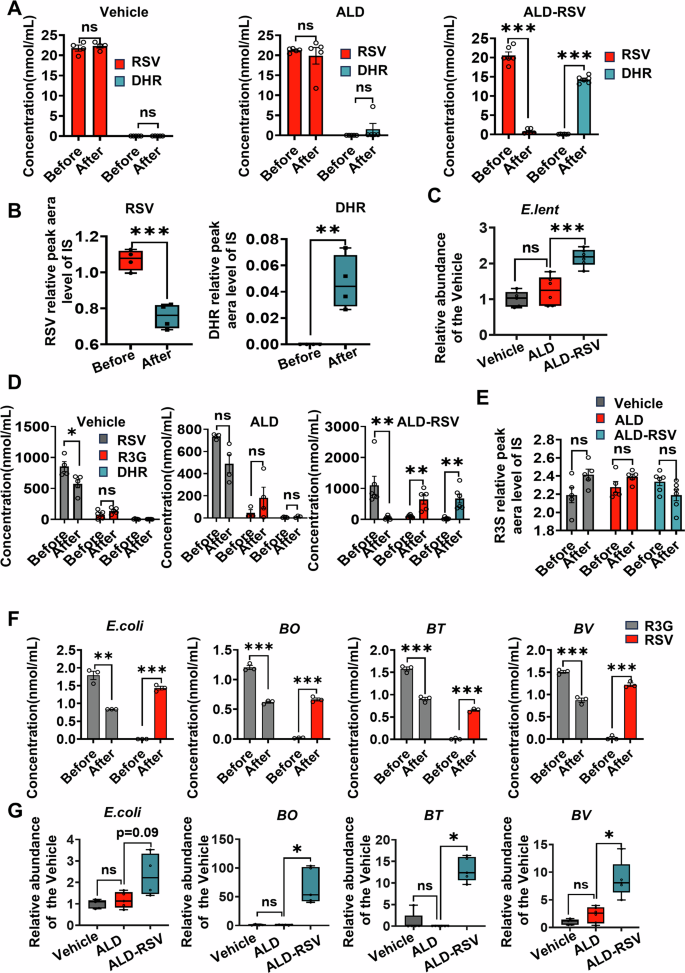

RSV tolerance correlates with the gut bacteria involved in its transformation after long-term treatment

Gut bacteria involved in RSV conversion metabolism was further screened in subsequent experiments. Mice feces were extracted from the Vehicle, ALD, and ALD-RSV groups and co-incubated with RSV to detect metabolites produced by gut bacteria. Only faecal bacteria from the ALD-RSV group were found to transform RSV. There was no significant change in RSV concentration in Vehicle group and ALD group after co-incubation of RSV with fecal bacteria for 8 h (Fig. 5A). However, the production of DHR, a metabolite of gut bacteria, was observed in the ALD-RSV group, with a significant decrease in RSV concentration of 96.06% (p < 0.001). It has been reported that E.lent bacteria can convert RSV to DHR14, which is also confirmed by co-culture of E.lent bacteria with RSV in this experiment (Fig. 5B). In addition, levels of this family were also found to be significantly elevated in the ALD-RSV group, but not in the Vehicle and ALD groups (Fig. 3D). We further detected the abundance of E.lent bacteria by fecal bacterial q-PCR, and found that the relative abundance of E.lent bacteria significantly increased in the ALD-RSV group (Fig. 5C). Therefore, long-term use of RSV leads to an increase in the relative abundance of E.lent bacteria, resulting in an increase in its own metabolism, which in turn leads to a decrease in its exposure, which may be a factor leading to a decrease in efficacy after long-term use of RSV.

Fig. 5: Gut bacteria contribute to reduced long-term efficacy of RSV in ALD mice.

A After long-term treatment with RSV, co-incubation of the fecal bacterial solution from ALD mice with RSV detected a significant production of the gut bacterial metabolite DHR. B The bacteria E.lent can metabolize RSV to generate DHR. C The abundance of bacteria E.lent was increased in ALD mice after long-term treatment with RSV. D When co-incubated with fecal bacteria from ALD-RSV group mice, R3G can be rapidly converted to RSV while generating DHR. E The fecal bacterial solution from the ALD-RSV group of mice is unable to metabolize R3S. F Gut bacteria such as E.coli, BO, BT, and BV can convert R3G into RSV. G The abundance of E.coli, BO, BT, and BV in the ALD-RSV group significantly increased. Vehicle pair-fed control group, ALD alcohol-related liver disease, ALD-RSV Resveratrol-treated ALD group, RSV resveratrol, R3G trans-resveratrol-3-O-β-D-glucuronide, R3S trans-resveratrol-3-sulfate sodium salt, DHR dihydroresveratrol, E.lent Eggerthella lenta, E.coli Escherichia coli, BV Bacteroides vulgatu, BT Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, BO Bacteroides ovatus. Intergroup differences were evaluated with unpaired Student’s t tests (two groups) or one-way ANOVA (three groups). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Significant differences between the indicated groups: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, no significance. The black hollow circles in the figures represent data points of different groups.

According to in vivo PK observation (Fig. 2C), R3G production was significantly increased in the multiple doses group, while there was no significant change in R3S production in both groups. Gut bacterial dopa decarboxylase converts levodopa to the more hydrophobic dopamine, i.e.,gut bacteria are involved in the secondary metabolism of the metabolite, which in turn affects the efficacy of the drug17. Therefore, in addition to E.lent bacteria, there may be other gut bacteria involved in the transformation of RSV and its metabolites. We then screened fecal bacteria that metabolized R3G and R3S. There was no significant change in R3G concentration before and after co-culture with fecal bacteria in Vehicle group and ALD group, and no DHR was observed in both groups. However, when co-cultured with fecal bacteria from the ALD-RSV group, R3G was rapidly converted to RSV and produced the bacterial metabolite DHR (Fig. 5D), but had no metabolic conversion activity against R3S (Fig. 5E). Referring to the previous studies on the effects of irinotecan and NSAIDS on the metabolism of gut bacteria β-Glucuronidase (β-GUS)18,19,20, it can be speculated that the transformation of R3G into RSV may be mediated by gut bacteria β-GUS. To identify β-GUS differential bacteria, we combined the NCBI database and 16S rRNA results (Fig. 3C, D) to screen for bacteria expressing β-GUS, including E.coli, BO, BT, and BV. After incubation of these single bacteria with R3G, R3G concentration decreased significantly and RSV was generated simultaneously (Fig. 5F). The abundance of individual bacteria that play a metabolic role in the fecal bacteria of ALD mice after long-term administration of RSV was detected by q-PCR (Fig. 5G). The results revealed that the abundance of E.coli, BO, BT, and BV in fecal bacteria increased significantly after long-term administration (Fig. 5G). Preliminary evaluation suggested that the significant increase in the relative abundance of E.coli, BO, BT, and BV resulted in accelerated hydrolysis of R3G in enterohepatic circulation, promoted the metabolism of R3G, and led to increased consumption of RSV, which may be another reason for the decreased efficacy of RSV after long-term medication.

To further explore the potential correlation between gut bacteria and RSV pharmacokinetic parameters, we conducted a correlation analysis of these two variables. Data were analyzed using the free online platform of Majorbio Cloud Platform (www.majorbio.com). E.lent metabolizes RSV, and the abundance of the family in which it is found was significantly and positively correlated with the AUC(0-t) and Cmax of RSV. The abundance of bacteroides and E.coli, which metabolize R3G, showed a significant positive correlation with AUC(0-t) and Cmax of R3G. However, these associations were not found between the abundance of gut bacteria and the pharmacokinetic parameters of R3S (Fig. 3E).

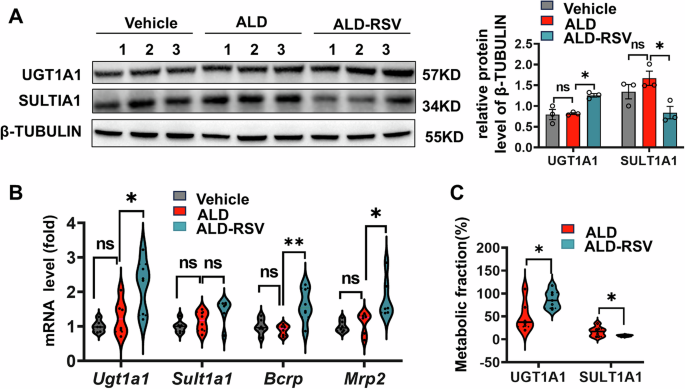

The expression of major RSV-metabolizing enzymes increased after its long-term treatment in ALD mice

RSV is metabolically transformed in the liver primarily by UGT1A1 and SULT1A1, and whether these host factors affect its long-term efficacy is uncertain, we further measured the expression changes of these enzymes. UGT1A1 mRNA level was significantly increased by 73.32% (p = 0.018) after long-term administration with RSV (Fig. 6B), and its protein expression was consistent with that of UGT1A1 gene expression, which was significantly increased by 53.90% (p < 0.012) (Fig. 6A). Further, the metabolic score of UGT1A1 was calculated by analyzing the AUC(0-t) changes of R3G and R3S, the main metabolites of RSV. The results showed that the metabolic score of UGT1A1 was significantly increased by 71.83% (p = 0.031) after long-term medication (Fig. 6C). The above phenomenon was not found on SULT1A1. Therefore, from the perspective of host factors, these findings suggest that long-term administration of RSV in ALD mice can promote the metabolic activity of UGT1A1 in the host, thereby reducing RSV exposure, which may be one of the reasons for the reduced effect of long-term administration.

Fig. 6: Long-term treatment with RSV increased the expression of major RSV-metabolizing enzymes in ALD mice.

A The expression of UGT1A1 in liver tissues of ALD mice was significantly increased at the protein level after long-term treatment with RSV. B After long-term treatment with RSV, the transcriptional expression of major metabolic enzymes and transport proteins in the liver of ALD mice significantly increased. C After long-term treatment with RSV, there was a significant increase in the proportion of RSV metabolized by UGT1A1 in ALD mice, while the proportion metabolized by SULT1A1 significantly decreased. Vehicle, pair-fed control group; ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; ALD-RSV, Resveratrol-treated ALD group. Intergroup differences were evaluated with unpaired Student’s t tests (two groups) or one-way ANOVA (three groups). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Significant differences between the indicated groups: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ns significance. The black circles in the figures represent data points of different group.

Discussion

In clinical practice, many chronic diseases require long-term medication. Even when administered according to the standard regimen listed in the drug label, some medications may show suboptimal efficacy over time and may even develop tolerance17,21,22. However, changing medications directly affects the treatment outcomes for patients, especially for diseases lacking preventive and therapeutic drugs, placing significant pressure. Therefore, uncovering factors influencing reduced drug efficacy or tolerance during long-term medication is crucial for guiding effective drug treatments and achieving personalized precision medicine.

The concentration level of a drug is the most direct factor affecting its efficacy, according to the classical theory of dose-response relationship for drugs, if the drug concentration falls below the therapeutic level after a period of use, it can lead to treatment failure. Drug concentration is the ultimate outcome of pharmacokinetic (PK) processes, and by monitoring changes in drug PK, changes in pharmacodynamic (PD) effects of the drug can be predicted, thereby reducing the occurrence of drug tolerance.

There are many factors influencing drug PK. In addition to common factors such as gender, age, physiology, disease status, liver and kidney function, environment, and diet, host factors including drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters have always been considered major determinants affecting drug PK23. In addition to host factors, gut bacteria, often referred to as the “second liver,” have emerged as a new factor influencing PK of drugs24,25,26. The gut bacteria comprise ~1013 bacterial populations, with a gene count more than 100 times that of the human genome, and possesses a diverse enzyme reservoir capable of drug metabolism27,28,29. Gut bacteria primarily convert drugs into hydrophobic compounds, thereby affecting the transformation of drugs and their metabolites, subsequently influencing PK and potentially altering the efficacy and toxicity of drugs30. For example, intestinal digoxin reductase can convert digoxin into its hydrophobic compound, dihydrodigoxin, leading to drug inactivation31. Intestinal dopamine decarboxylase (DDC) converts levodopa into the more hydrophobic dopamine, which may result in treatment failure for Parkinson’s disease. Moreover, some studies indicate that bacterial transporters also play a significant role in influencing drug PK32,33. Activation of bacterial efflux transporters can lead to drug efflux, reducing drug exposure and lowering drug efficacy. Conversely, using inhibitors of these transport proteins can increase drug exposure and efficacy in the body32,33. Additionally, the interaction between gut bacteria and commonly used medications (excluding antibiotics) is also complex. For instance, long-term use of metformin has been shown to alter microbial composition and function, which in turn affects th PK of metformin, thereby influencing its therapeutic effects. In clinical practice, chronic diseases often require long-term drug treatment, during which the spectrum of gut bacteria frequently undergoes changes. Considering the potential impact of gut bacteria on drug PK, it is foreseeable that intestinal microbiota will also influence the therapeutic outcomes of long-term treatment for chronic diseases. However, research in this area is limited.

Addressing drug tolerance is a challenge in precision medicine. In this study, RSV was effective in the early stages of long-term treatment in ALD mice, while it became less effective or even ineffective in later treatment, possibly leading to tolerance. Based on the classical dose-response relationship, changes in drug efficacy can be predicted by pharmacokinetic changes, which may be caused by changes in RSV exposure in vivo during long-term drug use. Therefore, exploring its internal influencing mechanism is of great help to elucidate the causes of long-term drug resistance to RSV.

Gut bacteria were found to be a new independent factor contributing to RSV tolerance during long-term treatment. There are following evidences to support this view: Firstly, multiple doses of RSV to treat ALD mice resulted in a decrease in the RSV parent drug with the production of a bacterial metabolite, DHR, which was not detected in single-dose treatment. In ALD mice treated with RSV over a long period of time, gut bacteria, in addition to being able to directly metabolize RSV to DHR (Fig. 5A), can also hydrolyze R3G to RSV and subsequently to DHR (Fig. 5D). In contrast, after ABX preconditioning eliminated gut bacteria, ALD-ABX mice had significantly higher exposure to RSV and its metabolites (except DHR) than ALD mice, suggesting that the gut bacteria play a role in RSV metabolism during long-term treatment (Fig. 4E). Secondly, gut bacteria associated with DHR production were identified by in vitro experiments. E.lent, which was previously reported to be able to convert RSV into DHR14, was also validated in our study. In addition, present study shows that E.coli, BO, BV, and BT strains that produce β-GUS can metabolize R3G to RSV, which has not been reported in previous literature. A significant increase in the abundance of E.lent, E.coli, BO, BV, and BT were observed based on 16S rRNA and gut bacteria qPCR following long-term administration with RSV to ALD mice. Referring to the previous studies on the effects of irinotecan and NSAIDS on the metabolism of gut bacteria.

β-GUS18,19,20, it can be speculated that the transformation of R3G into RSV may be mediated by gut bacteria β-GUS, while the mechanism of hydrolysis of R3G by bacteria producing β-GUS enzymes requires another study to elucidate. Finally, correlation analysis of RSV pharmacokinetic parameters and intestinal gut bacteria showed that the metabolism of RSV and R3G was affected by gut bacteria, and the abundance of related metabolic bacteria was positively correlated with RSV exposure in vivo (Fig. 3E). Therefore, gut bacteria play an important role in the reduction of RSV exposure after long-term treatment.

In addition to gut bacteria, changes in host factors can also affect RSV exposure after long-term treatment. The expression of host metabolic enzyme UGT1A1 was notably elevated after long-term treatment with RSV. UGT1A1 is responsible for the conversion of RSV to R3G, and increased enzyme expression will lead to faster metabolism of RSV, resulting in reduced exposure to RSV in the body, which may also be a cause of RSV tolerance.

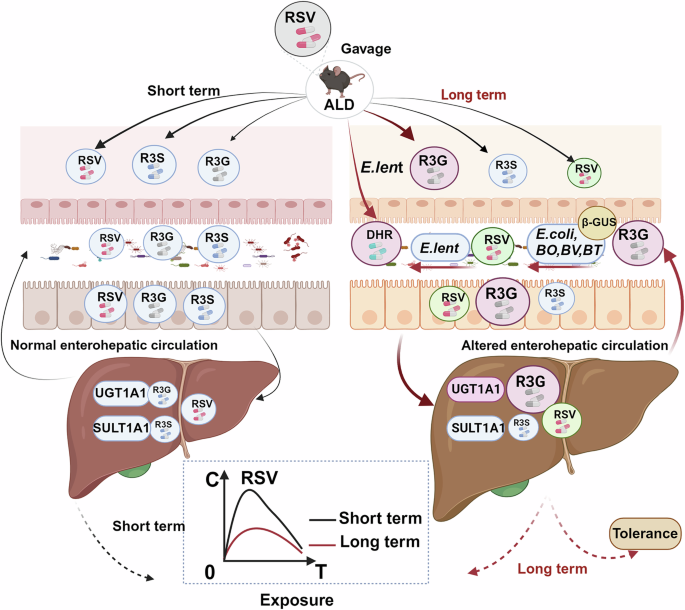

Gut bacteria and host factors may collectively reduce RSV exposure and lead to tolerance after long-term treatment in ALD mice (Fig. 7), which was created with BioRender.com. On the one hand, an adaptive alteration in the composition of the gut bacteria following long-term administration of RSV has been observed. This change has been shown to result in an increase in the number of bacteria capable of metabolizing RSV and R3G, This, in turn, has been demonstrated to lead to a reduction in the concentration of RSV. On the other hand, long-term administration of RSV has also been demonstrated to induce up-regulation of host metabolic enzyme UGT1A1, which accelerated RSV metabolism. Therefore, the alteration of gut bacteria and host factors both contributed to a decline in efficacy and ultimately lead to tolerance.

Fig. 7: Schematic diagram of the mechanism by which long-term RSV treatment in ALD mice enhances gut bacteria and host RSV metabolism, fostering tolerance.

Chronic RSV treatment upregulated UGT1A1, the enzyme converting RSV into its primary metabolite, trans-resveratrol-3-O-β-D-glucuronide (R3G). Long-term RSV administration increased the abundance of E.lent, a bacterium that metabolizes RSV to DHR, as well as bacteria capable of converting R3G to RSV (via β-GUS activity), including E.coli, BO, BT, and BV. The synergistic interaction between gut bacteria and host factors enhances RSV metabolism in ALD mice, promoting the development of tolerance. ALD alcohol-related liver disease, RSV resveratrol, R3G trans-resveratrol-3-O-β-D-glucuronide, R3S trans-resveratrol-3-sulfate sodium salt, DHR dihydroresveratro, E.lent Eggerthella lenta, E.coli Escherichia coli, BV Bacteroides vulgatu, BT Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, BO Bacteroides ovatus, β-GUS β-glucuronidase.

Although the current study could not distinguish between gut bacteria and host UGT1A1 enzyme change factors which play a major role in RSV tolerance, nor can it clarify the specific relationship between gut bacteria and host enzyme changes, the study yielded significant insights into the potential adaptive changes that may occur in the gut bacteria and the host factors following long-term administration of RSV during ALD therapy. These changes, which have been observed in previous studies, can influence drug metabolism, reduce drug exposure, and may also lead to decreased efficacy and the development of tolerance. Our findings clarified the issue of reduced efficacy due to accelerated metabolism that may arise with long-term administration of RSV for ALD, we can properly increase the dose of RSV, or inhibit the metabolism of RSV by interfering gut bacteria or host UGT1A1 enzyme to stabilize the therapeutic concentration of RSV, to avoid ALD therapy failure. Improvements can be made on a case-by-case basis, for example, by increasing the dose of the drug or improving drug exposure in the body by intervening in the drug metabolism pathway (gut bacteria and/or the host) to achieve enhanced efficacy. For the species differences between animal experiments and clinical studies, we will continue to provide more evidence for this view from clinical studies to provide better evidence in the future.

In a word, the study presents a systematic investigation of drug tolerance from the perspective of drug metabolism by gut bacteria and the host factors. The combined effects of gut bacteria and host factors facilitate the metabolism of RSV in ALD mice, thereby reducing exposure and creating tolerance during long-term treatment. This study reveals that the efficacy of RSV is not maintained consistently during long-term treatment of ALD. It underscores the critical importance of actively monitoring and strategically adjusting dosages to ensure enduring therapeutic efficacy. Moreover, this finding provides novel insights into the diminishing effectiveness of RSV over extended treatment durations and illuminates the mechanisms underlying drug tolerance, which may be applicable to other clinical therapies.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

RSV (purity: 99%, Lot No. E1711079) was procured from the Aladdin Industrial Corporation (Shanghai, China). R3G (purity: 97.23%, Lot No. 6-LXS-20-2) and R3S (purity: 96.76%, Lot No. 10-UPA -21-2) were procured from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, Canada). DHR (purity: 99.9%) was obtained from the Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The Lieber-DeCarli alcohol liquid diet (Lot No.TP-4030D) and the Lieber-DeCarli control liquid diet (Lot No.TP-4030C) were both procured from Trophic Animal Feed High-Tech Co., Ltd. (Nantong, China). The antibiotics utilized in the experiment were all sourced from Shenggong Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The single bacteria utilized in the experiment were procured from ATCC (Maryland, USA). The antibodies used in this study were obtained from the following sources: SULT1A1 from Bioworld (Nanjing, China); β-TUBULIN and UGT1A1 from Proteintech (Wuhan, China); CYP2E1 from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); and GAPDH from Abmart (Shanghai, China). The 2× SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix was obtained from Selleck (Texas, USA), and the All-In-One 5× RT MasterMix was purchased from Abm (Vancouver, Canada). DNA extraction was performed using the E.Z.N.A.® Soil DNA Kit from Omega Bio-Tek (Connecticut, USA). The mGAM was obtained from NISSUI PHARMACEUTICAL CO., LTD. (Tokyo, Japan), and Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) medium was purchased from Beijing Solebao Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Additionally, 40 μL heparin sodium-coated glass capillaries were acquired from Zibo Laixu Medical Equipment Co., Ltd. (Shandong, China). Mouse restraint was purchased from the Zhongke Life Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). All other reagents and supplies were commercially available.

Long-term treatment of RSV in ALD mice

To evaluate the therapeutic effects of long-term resveratrol (RSV) administration on ALD, we conducted a study in a mouse model, systematically monitoring dynamic changes in hepatic biochemical markers throughout the treatment period. Male C57BL/6J mice aged 8 to 10 weeks were purchased from Hunan Slikejingda Experiment Animal Co., Ltd. (Changsha, China). The mice were housed in the Laboratory Animal Facility of Central South University, with access to food and water ad libitum. All procedures were conducted in accordance with ethical and regulatory standards for animal experiments and strictly adhered to the relevant guidelines of the Experimental Animal Administration Committee of Central South University (No. CSU-2022-0006, Date: March 7, 2022, Changsha, China).

The experimental design is illustrated in Fig. 1A. The mice were randomly divided into three groups (n = 7 per group): the vehicle group (pair-fed control group), the ALD group (alcohol-fed Lieber-DeCarli model group), and the ALD group treated with RSV (ALD-RSV group). The ALD model was established in male C57BL/6J mice using a modified National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) protocol34. In brief, mice were initially fed ad libitum with the control Lieber-DeCarli diet for 5 days to allow acclimation to a liquid diet. Afterward, alcohol (EtOH)-fed groups are allowed free access to the alcohol Lieber-DeCarli diet containing 5% (v/v) alcohol for 10d, and the Vehicle groups are pair-fed with the isocaloric control diet. On the 16th day, the ALD group mice were gavaged with a single dose (5 g/kg) of alcohol and the Vehicle group mice were gavaged with the isocaloric maltose dextrin solution. Commencing on Day 17, the mice received daily oral administration of RSV (150 mg/kg suspended in 0.25% carboxymethyl cellulose sodium, CMC-Na) via gavage for a duration of 5 weeks. Both the Vehicle group and ALD treatment group were administered an equivalent volume of the solvent vehicle. During the RSV administration period, the ALD and ALD-RSV groups were maintained on the Lieber-DeCarli liquid diet supplemented with 5% (v/v) alcohol, while the Vehicle group received a pair-fed isocaloric Lieber-DeCarli diet without alcohol, with daily intake adjusted to match the consumption of the ALD group. Blood samples were collected weekly through retro-orbital bleeding using heparinized capillary tubes to monitor hepatic function parameters. At the end of the experiment, all mice were anesthetized using the inhalant anesthetic isoflurane. Before euthanasia by cervical dislocation, the absence of the righting reflex after isoflurane inhalation was confirmed to ensure complete unconsciousness. This method was chosen to minimize pain and distress to the animals. This study was approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Central South University (Approval No. CSU-2022-0006) and was conducted in strict compliance with international ethical guidelines for animal research. This method is also applicable to other animal experiments in this study. Following the experimental period, Body weight measurements were recorded weekly to monitor growth trends and overall health status throughout the study duration.

Pharmacokinetic study of RSV during long-term treatment in ALD Mice

To investigate factors influencing the efficacy changes of long-term RSV treatment in ALD mice, we assessed alterations in RSV exposure from a pharmacokinetic perspective. Experimental design process is shown in Fig. 2A. Twenty-one male C57BL/6J mice were randomly allocated into three experimental groups (n = 7 per group): (1) Control Single dose group, (2) ALD Single dose group, and (3) ALD Multiple doses group. ALD was established in male C57BL/6J mice following our previously described protocol. The Multiple doses group received daily oral gavage of RSV, initiated at day 17 post-ALD induction and maintained for 5 consecutive weeks. In parallel, both the Control Single dose group and ALD Single dose model group received identical volumes of vehicle solution (0.25% carboxymethyl cellulose sodium, CMC-Na) following the identical administration protocol. At the experimental endpoint, following a single oral gavage administration of RSV (150 mg/kg) to each mouse, serial blood samples were collected from the tail vein at predetermined time points (0, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h post-administration). Approximately 20 μL of blood was collected at each time point, and the samples were stored in a light-protected freezer at −80 °C until analysis by HPLC-MS/MS as previously described35. The determination of RSV and its main metabolites was performed using a Triple QuadTM 6500 HPLC-MS/MS system (AB Sciex, Concord, Ontario, Canada) with an ACE Excel 5 Super C18 column (50 mm × 2.1 mm, 5 μm, ACE, Kent, WA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of 5 mM ammonium acetate and acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.30 mL/min. This setup was used for the separation of RSV, R3G, R3S, DHR, and diethylstilbestrol (internal standard, IS). A 10 μL aliquot of mouse blood sample was mixed with 90 μL of methanol containing IS (5.48 ng/mL), vortexed, and centrifuged. The supernatant was transferred for HPLC-MS/MS analysis. The mass spectrometer operated in negative ion mode using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for detection. The precursor–product ion transitions were monitored at m/z 226.9–184.9 for RSV, m/z 403.1–227.3 for R3G, m/z 309.0–227.1 for R3S, 229.1/81.0 for DHR, and for m/z 267.4-237.3 for IS. The data were acquired using the Analyst software (Version 1.4.2, Concord, Ontario, Canada).

Gut bacteria analysis by 16S rRNA gene sequencing

The composition of the gut bacteria in the Vehicle, ALD, and ALD-RSV groups was analyzed by 16S rRNA analysis of fecal bacteria frozen in the presence of −80 °C. Isolation of total DNA from stool samples was carried out using the E.Z.N.A.® Stool DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) per the manufacturer’s directions. The hypervariable region V3-V4 of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were amplified with primer pairs 338F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’) and 806R (5’- GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) by an ABI GeneAmp® 9700 PCR thermocycler (ABI, CA, USA). The PCR product was extracted from 2% agarose gel and purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions and quantified using Quantus™ Fluorometer (Promega, USA).

Sequencing libraries were generated using the illumina miseq (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations. Raw FASTQ files were de-multiplexed using an in-house perl script, and then quality-filtered by fastp version 0.19.6 and merged by FLASH version 1.2.7. Then the optimized sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using UPARSE 7.1 with 97% sequence similarity level. Sequences with ≥97% similarity were assigned to the same operational taxonomic units (OTUs). The representative sequence for each OTU was screened for further annotation. Beta-diversity was estimated by calculating unweighted unifrac distances and then visualized by means of principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) was calculated to identify the bacterial taxa differentially enriched in different bacterial communities.

Effects of gut bacteria on the exposure of RSV in ALD mice

To further understand the effect of gut bacteria on exposure of RSV, we conducted a study in which pseudo-sterile mice were constructed. The mice were randomly divided into three groups (n = 7 per group): the vehicle group (pair-fed control group), the ALD group (alcohol-fed Lieber-DeCarli model group) and the ALD group treated with combined antibiotics (ALD-ABX group). The ALD mouse model was established using the same method as described previously. To observe the effect of gut bacteria on the exposure of RSV in the ALD model, The ALD mice were orally administered combined antibiotics including vancomycin (25 mg/kg), neomycin sulfate (50 mg/kg), ampicillin (50 mg/kg), and metronidazole (50 mg/kg), for seven consecutive days. The antibiotics were diluted 20 times in liquid feed of mice in the later stage to maintain a pseudo-sterile state. Following a single administration of RSV through the mouse tail, blood samples used for PK study were collected and stored in a −80 °C refrigerator away from light until analysis.

Verification of the ability of gut bacteria to metabolize RSV and its major metabolites

To verify the direct metabolic transformation of RSV and its metabolites by gut bacteria, fecal bacteria were co-incubated with RSV and its metabolites in vitro. The role of gut bacteria was determined by detecting the reduction of the parent drug and the generation of metabolites. Fecal samples from Vehicle, ALD, ALD-RSV group mice were mixed at 1:12 (g/mL) in sterile saline. The supernatant was taken and incubated using anaerobic medium (mGAM broth, 1: 9). After 24 h of anaerobic cultivation at 37 °C, a working solution of gut bacteria can be obtained. The drug stock solution (9.81 mg/mL RSV, 1 mg/mL R3G, and 1 mg/mL R3S) was diluted with culture solution in a 1:1000 ratio (v/v) to obtain the drug working solution, which was then mixed with the working solution of the gut bacteria in an equal amount in an anaerobic incubator at 37 °C. The RSV was incubated for 8 h, the R3G was incubated for 12 h, the R3S was incubated for 24 h. A total of 50 μL of the sample was incubated with the original solution, and 450 μL of ice acetonitrile containing IS was added to terminate the reaction.

Furthermore, single strains identified by 16S rRNA sequencing were further validated for their potential to metabolically transform RSV and its metabolites. E.lent bacteria were incubated with RSV using mGAM medium for 17 h. BO, BT, BV, and E.coli were incubated with R3G using BHI for 24 h. BV was incubated with R3G for 48 h. Three composite holes were used per time point. The incubation method and detection method were consistent with those previously employed for fecal bacteria incubation.

Finally, samples after incubation experiment were analyzed using HPLC-MS/MS with an ACE EXCEL 5 Super C18 column (50 × 2.1 mm, 5 μm). Mass spectrometry conditions were consistent with those used previously.

Liver histological

Small pieces of liver tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, cut into 5-μm-thick sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The degree of liver steatosis was examined under an inverted microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE Ts2R; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and then photographed. The scoring criteria for liver H&E pathology are shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Liver function analysis

Liver function and hepatic steatosis were evaluated by quantifying serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), as well as hepatic triglyceride (TG) content, using standardized assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China).

Immunoblotting

Mouse liver tissues were homogenized, and the lysate was prepared using RIPA (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The protein content was quantified using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay reagent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Proteins (30 μg) were separated using 4–20% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, depending on the molecular weights of the target proteins, and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The membrane was incubated with 5% nonfat milk for 2 hours at room temperature. Following incubation with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight, the membrane was then incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated secondary antibodies (Proteintech, Wuhan, China) for 1 h at room temperature. Imaging was conducted using an Immobilon Chemiluminescent HRP substrate and a ChemiDoc TM XRS+ Gel Imaging System (BIO-RAD, CA, USA). The densities of the protein bands were analyzed using Image Studio Lite (v. 5.2) software. The primary antibodies employed were mouse monoclonal antibodies, including anti-SULT1A1 (Bioworld, Visalia, CA, USA, 1:1000), anti-UGT1A1 (Bioworld, Visalia, CA, USA, 1:1000), CYP2E1 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, 1:2000), GAPDH (Abmart, Shanghai, China, 1:5000), and anti-β-TUBULIN (Proteintech, Wuhan, China, 1:5000). The relative expression of the target protein was quantified as the optical density (OD), which was normalized to the corresponding OD of β-TUBULIN or GAPDH.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR

Tissue mRNA was isolated using RNAiso Plus (Takara, Dalian, China), and total RNA reverse transcription was performed using an assay kit (Takara, Dalian, China). q-PCR-based detection of gene expression was conducted using 2 × SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Selleck, Texas, USA) and the LightCycler 480 real-time PCR system (Roche Diagnostics). The expression of each gene was normalized to that of the reference gene, β-actin. The q-PCR of single bacteria in fecal bacteria was performed using DNA extracted from reagent kits. The expression of each bacteria gene was normalized to that of the reference gene, 16S rRNA. The results are presented relative to the vehicle group according to the 2-ΔΔCt method. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6.

Statistical analysis

The GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was employed for the generation of the graph. The pharmacokinetic parameters of RSV and its metabolites were obtained through a noncompartmental analysis of the data using the Drug and Statistical software, Version 3.2.2 (Clinical Drug Evaluation Centre, Wannan Medical College, Wuhu, China). The maximal plasma concentration (Cmax) and time to Cmax (Tmax) were directly noted from the measured data. The elimination constant (ke) was calculated by the log-linear regression of the concentrations observed during the terminal phase of elimination, and the elimination half-life (t1/2) was then calculated as 0.693/ke. The area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC(0–t)) for the last measurable plasma concentration (Ct) was calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule. The area under the plasma concentration-time curve for time infinity (AUC(0–∞)) was calculated as AUC(0–t) + Ct/ke. Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22 (IBM Company, New York, NY, USA Intergroup differences were evaluated with unpaired Student’s t tests (two groups) or one-way ANOVA (three groups). A chi-square test was employed for nonparametric statistics, and significant differences were analyzed using two-tailed tests (p < 0.05).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.