Clinicopathological characteristics and prognostic factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a population-based study (original) (raw)

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is a primary liver malignancy originated from intrahepatic bile duct epithelial cells, whose incidence is second only to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[1](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR1 "Patel, T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 33, 1353–1357. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2001.25087

(2001)."). In comparison with cancer in the upper one third of biliary tract or the two-thirds located in the common hepatic duct bifurcation (Klatskin tumors), ICC is the most uncommon type of cholangiocarcinomas. Although ICC is rare, most patients are diagnosed at advanced and even lethal stage due to the great challenges in detection and therapy[2](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR2 "Blechacz, B., Komuta, M., Roskams, T. & Gores, G. J. Clinical diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8, 512–522.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2011.131

(2011).").Although rare, the incidence of ICC has been rising in the past decades[3](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR3 "Shaib, Y. H., Davila, J. A., McGlynn, K. & El-Serag, H. B. Rising incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: A true increase?. J. Hepatol. 40, 472–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.030

(2004)."), including Japan, Europe, Asia, North America and Australia[4](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR4 "Patel, T. Worldwide trends in mortality from biliary tract malignancies. BMC Cancer 2, 10.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-2-10

(2002)."),[5](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR5 "Khan, S. A. et al. Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours. J. Hepatol. 37, 806–813.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00297-0

(2002)."). However, the knowledge of ICC is currently limited, without clear definition of clinicopathological features as well as outcome[6](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR6 "Zhang, H., Yang, T., Wu, M. & Shen, F. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and surgical management. Cancer Lett. 379, 198–205.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2015.09.008

(2016)."). Therefore, in order to make clinicians have a better understanding of this rare disease, it is particularly important to deeply explore the clinicopathological features and prognosis of ICC.The NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, the most authoritative and largest cancer registry in North America7, covers approximately 30% of the total US population by selecting appropriate locations for representing population diversity[8](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR8 "Cahill, K. S. & Claus, E. B. Treatment and survival of patients with nonmalignant intracranial meningioma: Results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program of the National Cancer Institute. Clinical article. J. Neurosurg. 115, 259–267. https://doi.org/10.3171/2011.3.jns101748

(2011)."). As such, SEER is a valuable database to study such rare tumors[9](#ref-CR9 "Dudley, R. W. et al. Pediatric choroid plexus tumors: Epidemiology, treatments, and outcome analysis on 202 children from the SEER database. J. Neurooncol. 121, 201–207.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-014-1628-6

(2015)."),[10](#ref-CR10 "Dudley, R. W. et al. Pediatric low-grade ganglioglioma: Epidemiology, treatments, and outcome analysis on 348 children from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Neurosurgery 76, 313–319.

https://doi.org/10.1227/neu.0000000000000619

(2015) (discussion 319; quiz 319–320)."),[11](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR11 "Hankinson, T. C. et al. Short-term mortality following surgical procedures for the diagnosis of pediatric brain tumors: Outcome analysis in 5533 children from SEER, 2004–2011. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 17, 289–297.

https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.7.peds15224

(2016)."). In our study, ICC patients were retrospectively collected from SEER database to summarize clinical features and survival for patients with ICC to delineate factors influencing prognosis.Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The access of SEER database was signed by the SEER Research Data Agreement (19817-Nov2018), and relevant data were collected according to approved guidelines. All used data were publicly accessible and did not involve any non-human subjects according to the Office for Human Research Protection; therefore, institutional review board approval was exempted.

Study population

SEER*State v8.3.6 (released at August 8, 2019) was used to select and determine qualified subjects from 18 SEER regions from 2004 to 2015. ICC patients were identified according to ICD-O-3 site codes C22.1 or C22.0 (intrahepatic bile duct and liver) and ICD-O-3 histological codes of 8160/3[12](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR12 "Liu, J. et al. Prognostic factors and treatment strategies for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma from 2004 to 2013: Population-based SEER analysis. Transl. Oncol. 12, 1496–1503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2019.05.020

(2019)."). Patients were eliminated if: (1) had more than one tumor; (2) only clinically diagnosed or autopsy or death certificate; (3) without certain necessary clinicopathological data (AJCC stage and surgical style); (4) without prognosis information and cause of death; (5) with unknown marital status and race; (6) died within three months after surgery. The rest of subjects were enrolled as the initial cohort of SEER.Covariates and endpoint

Patient features were analyzed according to relevant factors: age (˂ 65, ≥ 65); sex (female, male); race (black, white or API/AI); marital status (unmarried, married); insured status (uninsured/unknown, any medicaid/insured); year of diagnosis (2004–2007, 2008–2011, 2012–2015); grade (grade I/II, grade III/IV, unknown); tumor size (˂ 5 cm, ≥ 5 cm, unknown); 6th edition of AJCC stage (stage I, II, III, IV); surgery (no surgery, local tumor excision/segmental resection, lobectomy/hepatectomy), chemotherapy (no/unknown, yes), radiotherapy (no/unknown, yes). To be specific, unmarried population included divorced or separated, single (never married or having a domestic partner) and widowed[13](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR13 "Liu, Y. L. et al. Marital status is an independent prognostic factor in inflammatory breast cancer patients: An analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 178, 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05385-8

(2019)."). Year of diagnosis was equally divided which was referred to a previous study[14](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR14 "Chen, Z. et al. Influence of marital status on the survival of adults with extrahepatic/intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget 8, 28959–28970.

https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.16330

(2017)."). The stratification of age and tumor size was also based on previous researches[15](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR15 "Shao, F., Qi, W., Meng, F. T., Qiu, L. & Huang, Q. Role of palliative radiotherapy in unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Population-based analysis with propensity score matching. Cancer Manag. Res. 10, 1497–1506.

https://doi.org/10.2147/cmar.s160680

(2018)."),[16](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR16 "Cheng, R., Du, Q., Ye, J., Wang, B. & Chen, Y. Prognostic value of site-specific metastases for patients with advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A SEER database analysis. Medicine 98, e18191.

https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000018191

(2019)."). API/AI means American Indian/AK Native, Asian/Pacific Islander. In addition, the staging of cancer is based on the 6th edition of AJCC stage system, which adapted to patients in the SEER database with a diagnosis time of 2004–2015.Overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) were taken as the study endpoint. OS was defined as the interval from diagnosis to all-cause death, while CSS referred to the interval from diagnosis to ICC-caused death. The cut-off date was set on November 31, 2018 because it was pre-determined until November 2018 (with death data) in accordance with SEER 2018 submission database.

Statistical analyses

Univariate analysis was estimated by Kaplan–Meier (K-M) method, followed by assessment of the differences of CSS and OS using log-rank test. Parameters with P value ≤ 0.2 in univariate analysis were further evaluated in multivariate Cox proportional hazard model[17](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR17 "Koletsi, D. & Pandis, N. Survival analysis, part 3: Cox regression. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 152, 722–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.07.009

(2017)."). Stratified Cox regression model was conducted, aiming at assessing the prognostic effects of chemotherapy and radiation in different subgroups stratified by surgery style. SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA, version 19.0) was employed for statistical analysis, and GraphPad Prism 5 was utilized for plotting survival curve. A two-sided _P_ < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.Results

Patients’ features

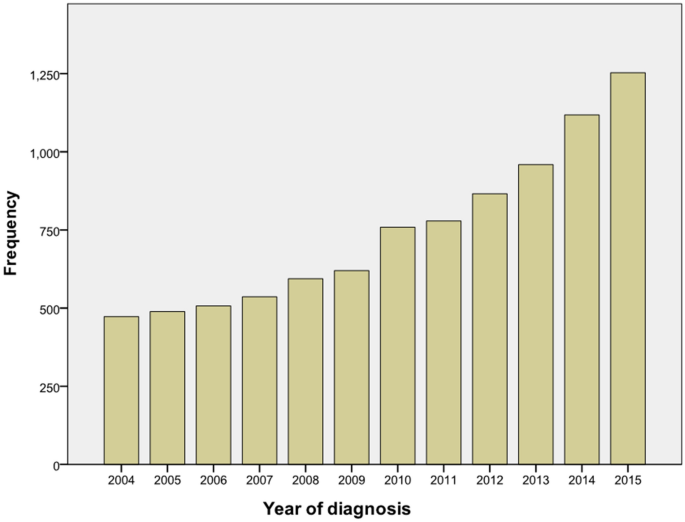

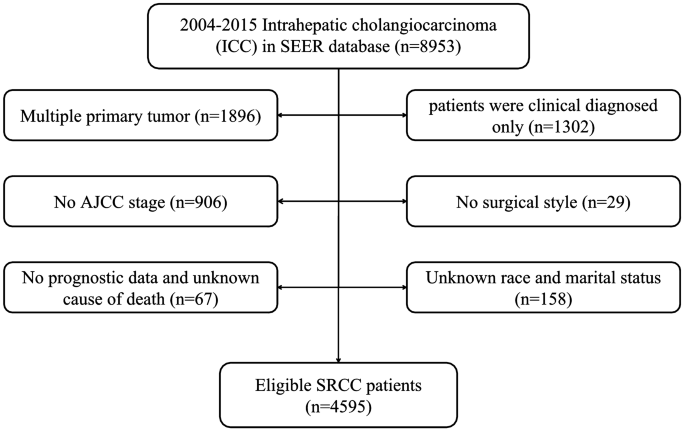

There were 8953 ICC patients from 2004–2015 totally, and the number of patients was increased year by year (Fig. 1). According to the exclusion criteria, 4595 patients were enrolled after screening. The specific screening process was shown in Fig. 2, and features of patients as well as therapeutic regimens were shown in Table 1. The median age was 65 (11–104) years old, with elderly patients (aged ≥ 65 years old) accounting for 51.7% and a male to female ratio of approximately 1:1. Most patients had primary tumors larger than 5 cm (43.4%), and advanced AJCC stage (stage III: 27.0% and stage IV: 48.5%). Most patients lost the surgical opportunity at diagnosis (79.1%); only 20.9% of patients underwent surgical treatment, including radiofrequency ablation and other local treatment. More than half of the patients received chemotherapy (53.7%)while only 15.1% received radiotherapy. Among the patients without surgery, only 2019 (55.5%) and 537 (14.8%) received chemotherapy or radiotherapy respectively.

Figure 1

Frequency map of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in SEER database from 2004 to 2015.

Figure 2

Flow chart for patient selection.

Table 1 The characteristics of the included intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients.

Patient survival and risk factors

The median survival of 4595 patients was 7.0 months (range 0–153 months). The 1-, 3- and 5-year CSS rates were 37.09%, 13.30%, and 8.96%, respectively. Meanwhile, the 1-, 3-and 5-year OS rates were 35.46%, 12.17% and 7.90%, respectively.

Univariate analyses revealed that all variables except race were predictors of CSS (all P ˂0.05). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that elderly age (HR 1.175, 95% CI 1.100–1.254, P < 0.001), male (HR 1.184, 95% CI 1.110–1.264, P < 0.001), diagnosis at 2008–2011 (HR 1.161, 95% CI 1.029–1.310, P = 0.015), higher histological grade (HR 1.411, 95% CI 1.277–1.558, P < 0.001), tumor size ≥ 5 cm (HR 1.115, 95% CI 1.019–1.219, P = 0.018), and advanced AJCC stage (P < 0.001) were independent indicators for poor prognosis. Meanwhile, API/AI race (HR 0.846, 95% CI 0.736–0.972, P = 0.019), married status (HR 0.904, 95% CI 0.846–0.967, P = 0.003), surgery [(local tumor excision/segmental resection) HR 0.322, 95% CI 0.282–0.369, P < 0.001 (lobectomy/hepatectomy) HR 0.295, 95% CI 0.268–0.339, P < 0.001], chemotherapy (HR 0.425, 95% CI 0.396–0.456, P < 0.001) and radiotherapy (HR 0.819, 95% CI 0.748–0.897, P < 0.001) were independent favorable indicators. The results of multivariate analysis for OS were similar. The results of univariate factor and multivariate analysis are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Univariate and multivariate analyses of cancer special survival (CSS) and overall survival (OS) for 4595 patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

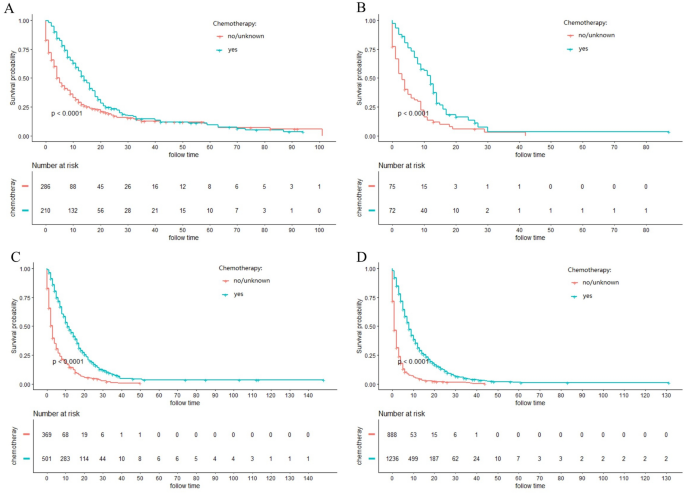

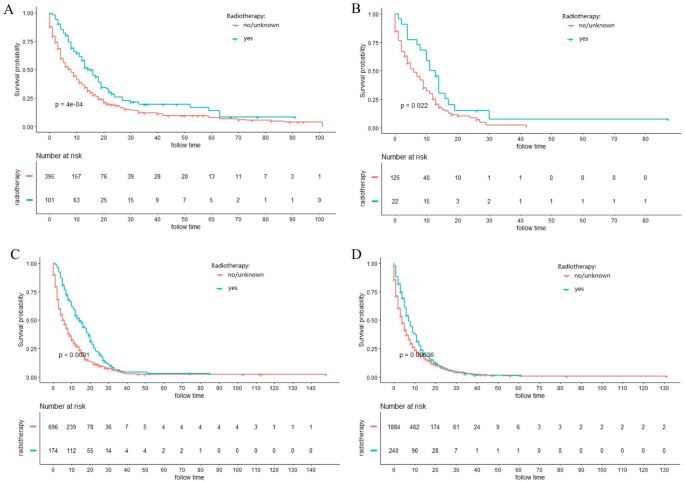

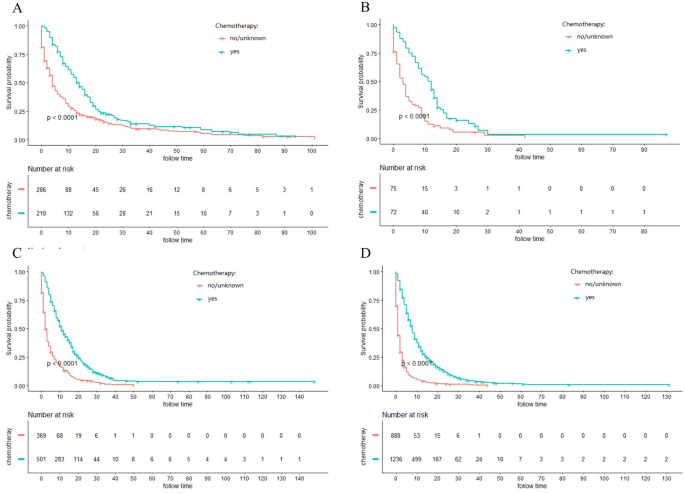

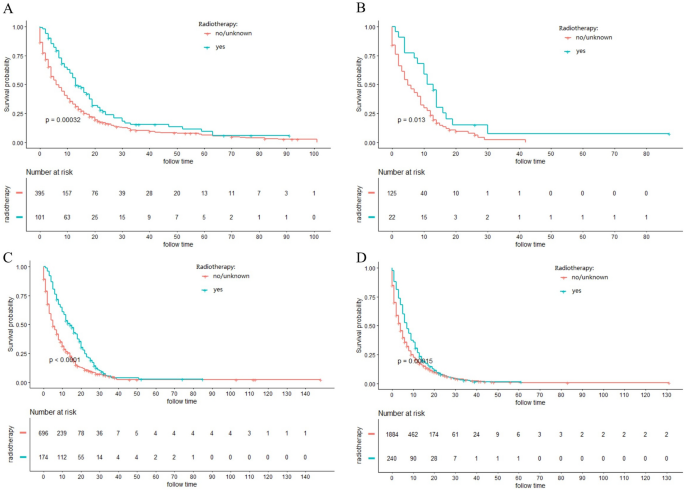

Stratified analysis of different surgery style

The majority of ICC patients (79.1%) were inoperable. In order to investigate the role of chemotherapy and radiotherapy in unresectable ICC patients, these patients were analyzed by K-M curves. Survival curves showed that unresectable ICC patients could significantly obtain survival benefit from chemotherapy or radiotherapy at different AJCC stage in terms of both CSS and OS (all P ˂ 0.001) (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6). For further assessment of prognostic effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy on patients with different surgery style, stratified Cox regression model was conducted. As demonstrated in Tables 3 and 4, compared to the non-chemotherapy group, chemotherapy group was associated with better CSS and OS in patients who did not receive any cancer-directed surgery (P < 0.001). But for patients with surgery did not show significant survival benefit (Table 3). In the stratified analysis of non-radiation group and radiotherapy group, similar results were obtained. Patients in the no surgery group received significant survival benefits after radiotherapy (P < 0.001), whether CSS or OS, while patients in the surgery group did not (Table 4).

Figure 3

Kaplan–Meier curves for cancer-specific survival (CSS) in different AJCC stage between chemotherapy and no-chemotherapy groups in unresectable ICC patients: (A) stage I; (B) stage II; (C) stage III; (D) stage IV.

Figure 4

Kaplan–Meier curves for cancer-specific survival (CSS) in different AJCC stage between radiotherapy and no-radiotherapy groups in unresectable ICC patients: (A) stage I; (B) stage II; (C) stage III; (D) stage IV.

Figure 5

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival (OS) in different AJCC stage between chemotherapy and no-chemotherapy groups in unresectable ICC patients: (A) stage I; (B) stage II; (C) stage III; (D) stage IV.

Figure 6

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival (OS) in different AJCC stage between radiotherapy and no-radiotherapy groups in unresectable ICC patients: (A) stage I; (B) stage II; (C) stage III; (D) stage IV.

Table 3 Role of chemotherapy related to cancer-specific survival (CSS) and overall survival (OS) in stratified Cox regression analysis.

Table 4 Role of radiotherapy related to cancer-specific survival (CSS) and overall survival (OS) in stratified Cox regression analysis.

Discussion

ICC is a subtype of bile duct adenocarcinoma involving liver small ducts[18](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR18 "Patel, T. Cholangiocarcinoma—Controversies and challenges. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8, 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2011.20

(2011)."), and the second most common primary liver malignancy after HCC[19](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR19 "Wu, W. et al. Pattern of distant extrahepatic metastases in primary liver cancer: A SEER based study. J. Cancer 8, 2312–2318.

https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.19056

(2017)."). Due to its rarity, few large-scale researches are available for instructive conclusions on proper management for ICC patients[20](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR20 "Shaib, Y. & El-Serag, H. B. The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin. Liver Dis. 24, 115–125.

https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-828889

(2004)."). For this purpose, we included a total of 4595 ICC patients to investigate the clinicopathological features and to examine survival-related factors of ICC.The incidence of ICC has been increased in the US in the last forty years (1973–2012), from 0.44 to 1.18 cases per 100,000[21](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR21 "Altman, A. M. et al. Current survival and treatment trends for surgically resected intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 9, 942–952. https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo.2017.11.06

(2018)."), and its incidence is also increasing throughout the world[22](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR22 "Saha, S. K., Zhu, A. X., Fuchs, C. S. & Brooks, G. A. Forty-year trends in cholangiocarcinoma incidence in the U.S.: Intrahepatic disease on the rise. Oncologist 21, 594–599.

https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0446

(2016)."). Previous studies report that ICC patients are elderly, without clear sex differences[23](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR23 "Lendoire, J. C., Gil, L. & Imventarza, O. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma surgery: The impact of lymphadenectomy. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 7, 53.

https://doi.org/10.21037/cco.2018.07.02

(2018)."), which are consistent with our study. Besides, we found that a large proportion of ICC patients had tumor size ≥ 5 cm and advanced AJCC stage. The outcome of ICC is extremely poor, with 5-year OS under 5% from 1975 to 1999[20](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR20 "Shaib, Y. & El-Serag, H. B. The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin. Liver Dis. 24, 115–125.

https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-828889

(2004)."). Nevertheless, our study found that the 5-year CSS and OS of ICC from 2004 to 2015 were 8.96% and 7.90%, respectively. From here we see that with the improved modern medical technology, the prognosis of ICC is improving.Currently, no consensus is achieved on risk stratification for ICC surveillance[24](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR24 "Chan, K. M. et al. Characterization of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after curative resection: Outcome, prognostic factor, and recurrence. BMC Gastroenterol. 18, 180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-018-0912-x

(2018)."). Despite hepatolithiasis, viral hepatitis B and C, cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis reported as risk factors by various researches, data from Eastern and Western countries are not identical[25](#ref-CR25 "El-Serag, H. B. et al. Risk of hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancers after hepatitis C virus infection: A population-based study of U.S. veterans. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 49, 116–123.

https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22606

(2009)."),[26](#ref-CR26 "Chapman, M. H. et al. Cholangiocarcinoma and dominant strictures in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: A 25-year single-centre experience. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 24, 1051–1058.

https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283554bbf

(2012)."),[27](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR27 "Welzel, T. M. et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in a low-risk population: A nationwide case-control study. Int. J. Cancer 120, 638–641.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.22283

(2007)."). Apart from AJCC staging and histological grade, tumor size ≥ 5 cm[24](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR24 "Chan, K. M. et al. Characterization of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after curative resection: Outcome, prognostic factor, and recurrence. BMC Gastroenterol. 18, 180.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-018-0912-x

(2018).") and marital status[14](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR14 "Chen, Z. et al. Influence of marital status on the survival of adults with extrahepatic/intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget 8, 28959–28970.

https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.16330

(2017).") have also been found to be significant prognostic factors for ICC. Additionally, we found that age, sex and race were also important prognostic factors.Radical surgery is the only curative treatment, including major liver resection with extended systematic lymph node (LN) dissection[28](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR28 "Luo, X. et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors of surgical therapy for all potentially resectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A large single-center cohort study. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 18, 562–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2447-3

(2014)."), which is recommended by most institutes. However, the resectable rate of ICC is still low, varying from 19 to 74% globally[29](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR29 "Bektas, H. et al. Surgical treatment for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in Europe: A single center experience. J. Hepato-biliary-pancreat. Sci. 22, 131–137.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.158

(2015)."). In our study, only 20.9% of patients underwent surgical treatment. Unresectable ICC patients are generally treated by systemic chemotherapy. ABC-02 trial revealed significant survival advantage in patients with advanced biliary cancer who were treated by gemcitabine/cisplatin combined chemotherapy than those with gemcitabine alone. Other combined regimens included gemcitabine- or fluorouracil-based chemotherapy[6](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR6 "Zhang, H., Yang, T., Wu, M. & Shen, F. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and surgical management. Cancer Lett. 379, 198–205.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2015.09.008

(2016)."). NCCN guidelines recommend radiation for subjects with positive regional LN or microscopic tumor margins (R1) following cancer-directed resection[30](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR30 "Gil, E. et al. Predictors and patterns of recurrence after curative liver resection in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, for application of postoperative radiotherapy: A retrospective study. World J. Surg. Oncol. 13, 227.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-015-0637-z

(2015)."),[31](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR31 "Song, S. et al. Locoregional recurrence after curative intent resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Implications for adjuvant radiotherapy. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 17, 825–829.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-015-1312-0

(2015)."). And our research found that significant survival benefits of radiation and chemotherapy in non-surgery group according to stratified Cox model (_P_ < 0.0001), which were consistent to previous studies[32](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR32 "Jackson, M. W. et al. Treatment selection and survival outcomes with and without radiation for unresectable, localized intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer J. (Sudbury, Mass.) 22, 237–242.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ppo.0000000000000213

(2016)."),[33](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR33 "Cuneo, K. C. & Lawrence, T. S. Growing evidence supports the use of radiation therapy in unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer J. (Sudbury, Mass.) 22, 243–244.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ppo.0000000000000212

(2016).").With using advanced technologies like next-generation sequencing (NGS) in ICC, recent research starts to reveal the genetic and molecular processes behind carcinogenesis. The results concluded through empirically studying the genome profiling, epidemiology and experiments offer novel insights into genomic formation, risk factors, cellular origins and constructing tumor microenvironment to the pathogeny of ICC. As a recent retrospective study verifies, the treatment with blockage of Her-2/neu in ICC patients suffering gene amplification has great potential[34](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR34 "Javle, M. et al. HER2/neu-directed therapy for biliary tract cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 8, 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-015-0155-z

(2015)."). Immunotherapeutic progress can also offer new opportunities for ICC therapy[35](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR35 "Takahashi, R. et al. Current status of immunotherapy for the treatment of biliary tract cancer. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 9, 1069–1072.

https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.23844

(2013)."). After PD-1 inhibitor treatment, a complete response was founded in the chemotherapy refractory metastatic ICC patient who suffers mismatch-repair deficiency (dMMR)[36](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR36 "Le, D. T. et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2509–2520.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1500596

(2015)."). Unfortunately, there is no information on molecular genetic profiles and targeted therapy in the SEER database.SEER database is the largest publicly accessible and authoritative source on cancer incidence and survival. Therefore, our findings could guide clinical management by using the large-scale, reliable research dataset. As far as we know, our study is largest population-based one to detect prognostic indicators in ICC. Inevitably, there are also several limitations in our study. Firstly, due to the nonrandomized nature of this study, selection bias is inevitable[9](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR9 "Dudley, R. W. et al. Pediatric choroid plexus tumors: Epidemiology, treatments, and outcome analysis on 202 children from the SEER database. J. Neurooncol. 121, 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-014-1628-6

(2015)."),[11](/articles/s41598-021-83149-5#ref-CR11 "Hankinson, T. C. et al. Short-term mortality following surgical procedures for the diagnosis of pediatric brain tumors: Outcome analysis in 5533 children from SEER, 2004–2011. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 17, 289–297.

https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.7.peds15224

(2016)."). Secondly, certain important factors, including tumor gross type, depth of invasion, status of harvested lymph node, molecular-genetic profiles, metabolic abnormalities of liver and chronic liver disease (viral infection and cirrhosis), were inaccessible in SEER dataset. Thirdly, detailed data on chemotherapy and radiotherapy were not available. Although it is better to obtain more details, we believed that the present available data from SEER database could fit our research objectives very well. Further studies should investigate the above concerns.Conclusions

In the present study, we investigated the clinicopathological features and survival of ICC patients. Age, sex, years of diagnosis, grade, tumor size, race, AJCC stage, married status, surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy were significantly associated with prognosis. For patients without surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy showed significant benefits to improve survival. Hopefully, our findings are of great significance for clinical management and future prospective studies for ICC.

References

- Patel, T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 33, 1353–1357. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2001.25087 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Blechacz, B., Komuta, M., Roskams, T. & Gores, G. J. Clinical diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8, 512–522. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2011.131 (2011).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Shaib, Y. H., Davila, J. A., McGlynn, K. & El-Serag, H. B. Rising incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: A true increase?. J. Hepatol. 40, 472–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.030 (2004).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Patel, T. Worldwide trends in mortality from biliary tract malignancies. BMC Cancer 2, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-2-10 (2002).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Khan, S. A. et al. Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours. J. Hepatol. 37, 806–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00297-0 (2002).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Zhang, H., Yang, T., Wu, M. & Shen, F. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and surgical management. Cancer Lett. 379, 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2015.09.008 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yu, J. B., Gross, C. P., Wilson, L. D. & Smith, B. D. NCI SEER public-use data: Applications and limitations in oncology research. Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.) 23, 288–295 (2009).

Google Scholar - Cahill, K. S. & Claus, E. B. Treatment and survival of patients with nonmalignant intracranial meningioma: Results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program of the National Cancer Institute. Clinical article. J. Neurosurg. 115, 259–267. https://doi.org/10.3171/2011.3.jns101748 (2011).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Dudley, R. W. et al. Pediatric choroid plexus tumors: Epidemiology, treatments, and outcome analysis on 202 children from the SEER database. J. Neurooncol. 121, 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-014-1628-6 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Dudley, R. W. et al. Pediatric low-grade ganglioglioma: Epidemiology, treatments, and outcome analysis on 348 children from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Neurosurgery 76, 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1227/neu.0000000000000619 (2015) (discussion 319; quiz 319–320).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hankinson, T. C. et al. Short-term mortality following surgical procedures for the diagnosis of pediatric brain tumors: Outcome analysis in 5533 children from SEER, 2004–2011. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 17, 289–297. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.7.peds15224 (2016).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Liu, J. et al. Prognostic factors and treatment strategies for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma from 2004 to 2013: Population-based SEER analysis. Transl. Oncol. 12, 1496–1503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2019.05.020 (2019).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Liu, Y. L. et al. Marital status is an independent prognostic factor in inflammatory breast cancer patients: An analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 178, 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05385-8 (2019).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chen, Z. et al. Influence of marital status on the survival of adults with extrahepatic/intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget 8, 28959–28970. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.16330 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Shao, F., Qi, W., Meng, F. T., Qiu, L. & Huang, Q. Role of palliative radiotherapy in unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Population-based analysis with propensity score matching. Cancer Manag. Res. 10, 1497–1506. https://doi.org/10.2147/cmar.s160680 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cheng, R., Du, Q., Ye, J., Wang, B. & Chen, Y. Prognostic value of site-specific metastases for patients with advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A SEER database analysis. Medicine 98, e18191. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000018191 (2019).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Koletsi, D. & Pandis, N. Survival analysis, part 3: Cox regression. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 152, 722–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.07.009 (2017).

Article Google Scholar - Patel, T. Cholangiocarcinoma—Controversies and challenges. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8, 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2011.20 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wu, W. et al. Pattern of distant extrahepatic metastases in primary liver cancer: A SEER based study. J. Cancer 8, 2312–2318. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.19056 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Shaib, Y. & El-Serag, H. B. The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin. Liver Dis. 24, 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-828889 (2004).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Altman, A. M. et al. Current survival and treatment trends for surgically resected intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 9, 942–952. https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo.2017.11.06 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Saha, S. K., Zhu, A. X., Fuchs, C. S. & Brooks, G. A. Forty-year trends in cholangiocarcinoma incidence in the U.S.: Intrahepatic disease on the rise. Oncologist 21, 594–599. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0446 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lendoire, J. C., Gil, L. & Imventarza, O. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma surgery: The impact of lymphadenectomy. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 7, 53. https://doi.org/10.21037/cco.2018.07.02 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Chan, K. M. et al. Characterization of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after curative resection: Outcome, prognostic factor, and recurrence. BMC Gastroenterol. 18, 180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-018-0912-x (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - El-Serag, H. B. et al. Risk of hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancers after hepatitis C virus infection: A population-based study of U.S. veterans. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 49, 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22606 (2009).

Article Google Scholar - Chapman, M. H. et al. Cholangiocarcinoma and dominant strictures in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: A 25-year single-centre experience. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 24, 1051–1058. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283554bbf (2012).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Welzel, T. M. et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in a low-risk population: A nationwide case-control study. Int. J. Cancer 120, 638–641. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.22283 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Luo, X. et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors of surgical therapy for all potentially resectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A large single-center cohort study. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 18, 562–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2447-3 (2014).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Bektas, H. et al. Surgical treatment for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in Europe: A single center experience. J. Hepato-biliary-pancreat. Sci. 22, 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.158 (2015).

Article Google Scholar - Gil, E. et al. Predictors and patterns of recurrence after curative liver resection in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, for application of postoperative radiotherapy: A retrospective study. World J. Surg. Oncol. 13, 227. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-015-0637-z (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Song, S. et al. Locoregional recurrence after curative intent resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Implications for adjuvant radiotherapy. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 17, 825–829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-015-1312-0 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jackson, M. W. et al. Treatment selection and survival outcomes with and without radiation for unresectable, localized intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer J. (Sudbury, Mass.) 22, 237–242. https://doi.org/10.1097/ppo.0000000000000213 (2016).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Cuneo, K. C. & Lawrence, T. S. Growing evidence supports the use of radiation therapy in unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer J. (Sudbury, Mass.) 22, 243–244. https://doi.org/10.1097/ppo.0000000000000212 (2016).

Article Google Scholar - Javle, M. et al. HER2/neu-directed therapy for biliary tract cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 8, 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-015-0155-z (2015).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Takahashi, R. et al. Current status of immunotherapy for the treatment of biliary tract cancer. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 9, 1069–1072. https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.23844 (2013).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Le, D. T. et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2509–2520. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1500596 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Author information

Author notes

- These authors contributed equally: Tian-hua Yu and Xin Chen.

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Blood Transfusion, China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, Jilin, China

Tian-hua Yu - Department of Radiology, the First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, Jilin, China

Xin Chen - Shihezi University, Shihezi, Xinjiang, China

Xuan-he Zhang - Rehabilitation Medicine Department, China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, Jilin, China

Er-chi Zhang - Department of Gastrointestinal Colorectal and Anal Surgery, China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, Jilin, China

Cai-xia Sun

Authors

- Tian-hua Yu

- Xin Chen

- Xuan-he Zhang

- Er-chi Zhang

- Cai-xia Sun

Contributions

C.S. and X.C. conceived the study. T.Y. searched the database and literature. T.Y., X.Z. and E.Z. discussed and analyzed the data. T.Y. wrote the manuscript. X.Z., X.C. and E.Z. revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence toEr-chi Zhang or Cai-xia Sun.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, Th., Chen, X., Zhang, Xh. et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognostic factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a population-based study.Sci Rep 11, 3990 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83149-5

- Received: 03 October 2020

- Accepted: 29 January 2021

- Published: 17 February 2021

- Version of record: 17 February 2021

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83149-5