Nationwide analysis of renal outcomes in chronic hepatitis B patients treated with Tenofovir Alafenamide vs. Entecavir (original) (raw)

Introduction

Decline in renal function is a significant clinical concern for patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB), who have a higher prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) compared to the general population. According to the Korean National Health Insurance Service data, since 2019, the prevalence of CKD in patients with chronic hepatitis B has been approximately 3%, compared to around 1.2% in a control group[1](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR1 "Kim, L. Y. et al. The epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in korea: 15-Year analysis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 39, e22. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e22

(2024)."). Additionally, this decline in renal function is associated with the future prognosis of CHB and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, necessitating careful monitoring[2](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR2 "Kim, D. Y. Changing etiology and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: Asia and worldwide. J. Liver Cancer. 24, 62–70.

https://doi.org/10.17998/jlc.2024.03.13

(2024)."),[3](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR3 "Jang, W. et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of Korean patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with respect to etiology. J. Liver Cancer. 22, 158–166.

https://doi.org/10.17998/jlc.2022.09.18

(2022).").While antiviral therapies are essential for managing CHB, it can adversely affect renal function, making the selection of appropriate medications crucial for high-risk groups[4](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR4 "Hsu, Y. C., Tseng, C. H. & Kao, J. H. Safety considerations for withdrawal of nucleos(t)ide analogues in patients with chronic hepatitis B: first, do no harm. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 29, 869–890. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2022.0420

(2023)."). Studies have demonstrated that antiviral therapy can accelerate the progression of CKD compared to non-treated patient groups[5](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR5 "Hong, H. et al. Longitudinal changes in renal function in patients with chronic hepatitis B on antiviral treatment. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 59, 515–525.

https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.17819

(2024)."). Among antiviral agents, Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (TDF) has been reported to cause higher rates of CKD and greater reductions in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) than other antiviral medications[4](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR4 "Hsu, Y. C., Tseng, C. H. & Kao, J. H. Safety considerations for withdrawal of nucleos(t)ide analogues in patients with chronic hepatitis B: first, do no harm. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 29, 869–890.

https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2022.0420

(2023)."),[6](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR6 "Jung, W. J. et al. Effect of Tenofovir on renal function in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Med. (Baltim). 97, e9756.

https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000009756

(2018)."),[7](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR7 "Jung, C. Y., Kim, H. W., Ahn, S. H., Kim, S. U. & Kim, B. S. Tenofovir is associated with higher risk of kidney function decline than Entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20 (e952), 956–958.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2021.05.032

(2022)."). This has raised significant concerns about its long-term use in patients with pre-existing renal issues or those at higher risk of renal decline[8](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR8 "Lee, H. A. & Seo, Y. S. Current knowledge about biomarkers of acute kidney injury in liver cirrhosis. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 28, 31–46.

https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2021.0148

(2022).").To address these concerns, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines recommend using Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF) or Entecavir (ETV) instead of TDF for patients aged 60 years or older, or those with renal alterations[9](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR9 "European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address, E. E. E. & European association for the study of the, L. EASL 2017 clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J. Hepatol. 67, 370–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021

(2017)."). However, despite the well-documented renal function decline associated with TDF, comprehensive comparative studies on the renal impacts of TAF and ETV are still lacking[10](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR10 "Liang, L. Y. & Wong, G. L. Unmet need in chronic hepatitis B management. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 25, 172–180.

https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2018.0106

(2019)."). A recent study conducted in Korea aimed to address this gap by comparing the outcome of 149 patients treated with ETV to those of 149 patients treated with TAF[11](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR11 "Jung, C. Y., Kim, H. W., Ahn, S. H., Kim, S. U. & Kim, B. S. Higher risk of kidney function decline with Entecavir than Tenofovir Alafenamide in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 42, 1017–1026.

https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.15208

(2022)."). The study indicated that renal function declined more rapidly in the ETV group compared to the TAF group. However, the limited sample size and scope of this study constrain the ability to draw the definitive conclusions from these findings.Thus, the aim of this study is to compare the progression to CKD and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B who are administered either TAF or ETV. To obtain more robust conclusions, this study utilized nationwide data from the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA).

Results

Baseline characteristics before and after PSM

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of patients in two cohorts—those with normal renal function and those with CKD—both before and after propensity score matching (PSM). In the normal renal function cohort (n = 60,178) before PSM, the average age was 51.9 years, with 60.4% male patients. Prior to PSM, the ETV group was older (55.3 years vs. 48.2 years) and had a higher proportion of males (62.8% vs. 57.8%) compared to the TAF group. The prevalence of hypertension (39.2% vs. 24.0%) and diabetes (33.2% vs. 21.8%) was significantly higher in the ETV group compared to the TAF group. However, after PSM, the average age in both groups was 47.7 years, with no statistically significant difference. The proportion of males was similar in both groups, at 63.4%. There were no significant differences between the groups regarding the duration of antiviral medication (575 days), the prevalence of diabetes (10.6%), and hypertension (14.1%).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics before and after propensity score matching.

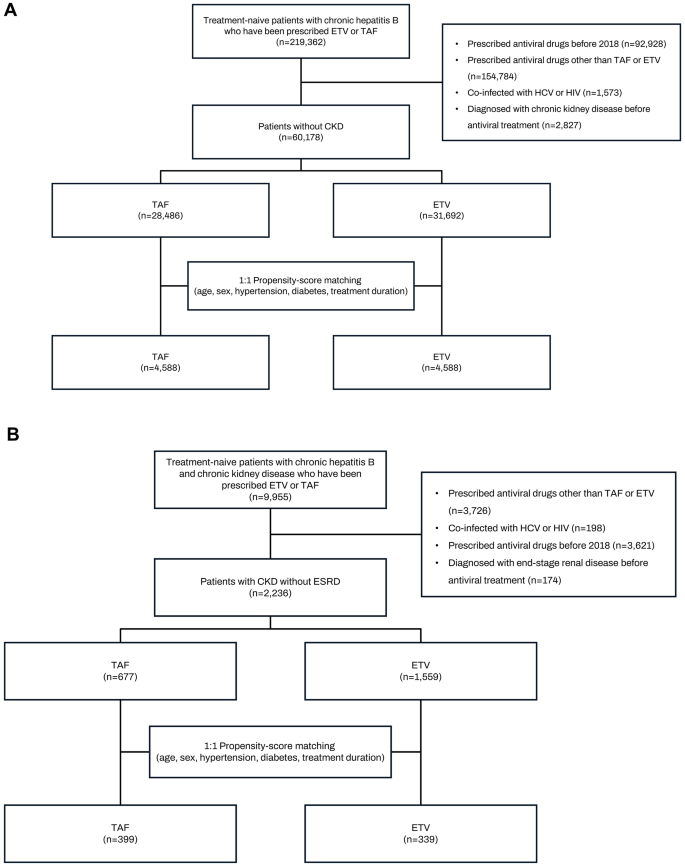

In the CKD cohort (n = 2,236) before PSM, the average age was 60.7 years, with 69.9% male patients. Prior to PSM, the ETV group was older and had a higher proportion of males compared to the TAF group. Additionally, the ETV group had higher rates of hypertension and diabetes. After PSM, the TAF and ETV groups were matched in terms of age, gender, duration of antiviral medication, and the rates of diabetes and hypertension (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Flow chart for patients. (A) patients with normal renal function (B) patients with chronic kidney disease.

Incidence and risk factors for CKD with ETV and TAF

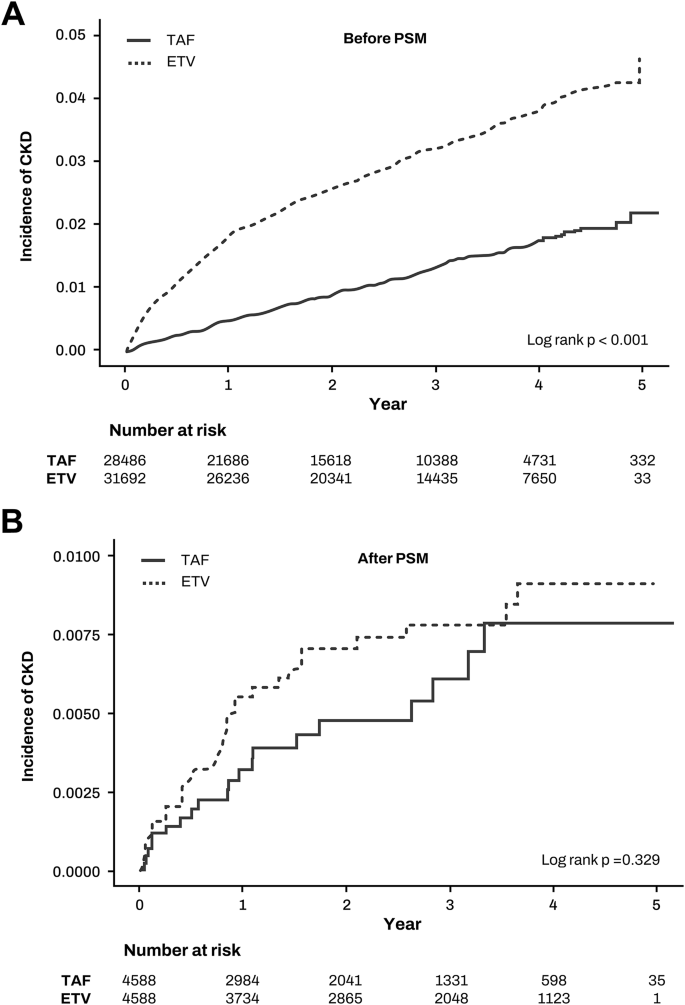

First, we calculated the incidence rates of CKD following antiviral therapy in patients with normal kidney function (Table 2). Before PSM, the CKD incidence rates were 10.88 per 1000 person-years for ETV and 4.48 per 1000 person-years for TAF, with the ETV group showing a significantly higher CKD incidence compared to the TAF group (incidence rate ratio 2.43, 95% CI 2.13–2.77, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2a). After PSM, the CKD incidence rates were 2.67 per 1000 person-years for ETV and 2.22 per 1000 person-years for TAF, with no significant difference between the groups (incidence rate ratio 1.20, 95% CI 0.69–2.10, p = 0.523) (Fig. 2b).

Table 2 Incidence of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease by antiviral agents.

Fig. 2

Incidence of chronic kidney disease between TAF and ETV groups. (A) before propensity score matching (B) after propensity score matching.

We conducted Cox regression analysis to identify risk factors for CKD development. In the pre-PSM cohort, ETV, age, male sex, hypertension, and diabetes were identified as risk factors (Supplementary Table S1). For PSM-matched patients, Cox regression analysis revealed that older age, hypertension, and diabetes were significant risk factors for CKD (Table 3). However, the type of antiviral medication was not a clinically significant factor (hazard ratio [HR] 1.223, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 0.691–2.164, p = 0.489).

Table 3 Cox regression analysis for chronic kidney disease after PSM.

Subgroup analysis was performed by presence or absence of cirrhosis, HCC and age groups (≥ 60 years or < 60 years). ETV demonstrated a non-significant trend toward an increased risk of CKD occurrence among patients with cirrhosis (HR 2.96, 95% CI 0.81–10.74, p = 0.101). However, no statistically significant difference in CKD incidence was observed between the two treatment groups in patients without cirrhosis (Supplementary Table S3). Similarly, subgroup analyses stratified by the presence or absence of HCC and by age group (≥ 60 years vs. <60 years) revealed no significant differences in CKD occurrence between the TAF and ETV groups (Supplementary Table S4, S5). Kaplan-Meier curve also showed no statistically significant differences between TAF and ETV in subgroups of with or without cirrhosis, HCC, and age ≥ 60 years or < 60 years (Supplementary Figure S1).

Incidence and risk factors for ESRD with ETV and TAF

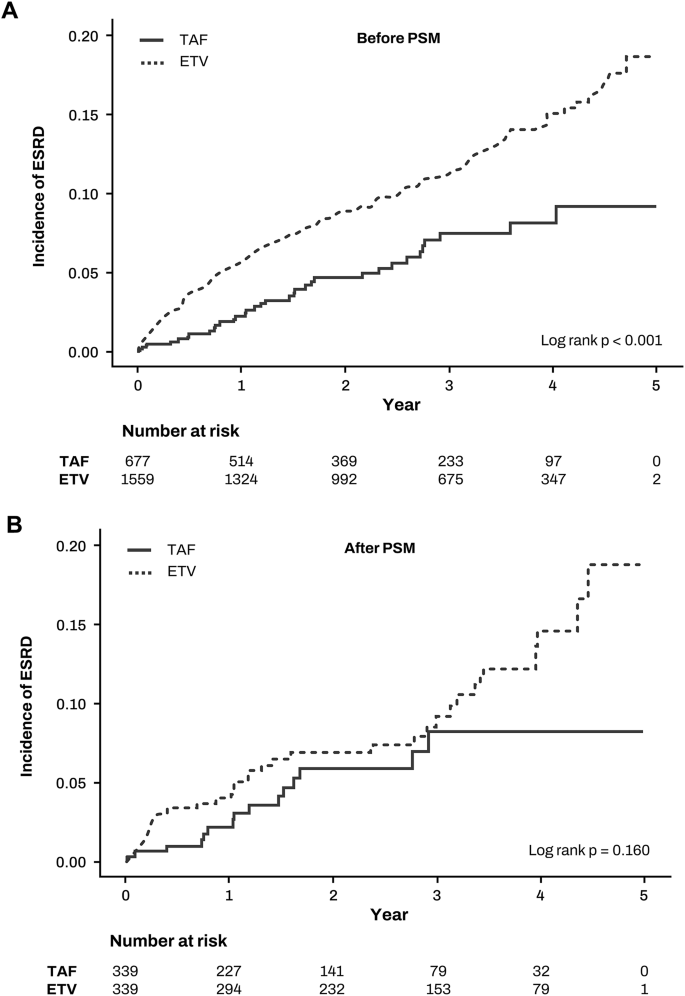

Next, we calculated the incidence rates of ESRD following antiviral therapy in patients with CKD (Table 2). Before PSM, the ESRD incidence rates were 40.33 per 1000 person-years for ETV and 22.13 per 1000 person-years for TAF, with the ETV group exhibiting a significantly higher ESRD incidence compared to the TAF group (incidence rate ratio 1.82, 95% CI 1.26–2.63, p = 0.001) (Fig. 3a). After PSM, the ESRD incidence rates were 35.27 per 1000 person-years for ETV and 23.64 per 1000 person-years for TAF, showing no significant difference between the groups (incidence rate ratio 1.49, 95% CI 0.81–2.75, p = 0.198) (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3

Incidence of end-stage renal disease between TAF and ETV groups. (A) before propensity score matching (B) after propensity score matching.

We performed Cox regression analysis to identify risk factors for ESRD development. In the pre-PSM cohort, ETV, male sex, duration of antiviral medication, hypertension, and diabetes were identified as risk factors (Supplementary Table S2). For PSM-matched patients, (Table 4). In both univariate and multivariate analyses, the type of antiviral medication was not clinically significant factor in the development of ESRD (Table 4).

Table 4 Cox regression analysis for end stage renal disease after PSM.

In the subgroup analyses stratified by the presence or absence of cirrhosis, the presence or absence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and age group (≥ 60 years vs. <60 years), no statistically significant difference was observed in the incidence of ESRD between the ETV and TAF groups (Supplementary Figure S2). However, in the subgroup of patients with HCC, the ETV group demonstrated a statistically significantly higher incidence of ESRD compared to the TAF group, in which no ESRD events were observed (ETV incidence rate 6.74 per 1,000 person-years; 95% CI 3.03–15.01; Supplementary Table S4). In all other subgroups, no statistically significant differences in ESRD incidence rates or incidence rate ratios were observed between the two treatment groups (Supplementary Tables S3–S5).

Discussion

Our study found no significant difference in the incidence of CKD or ESRD between patients with CHB treated with TAF or ETV. Previous study have suggested that ETV is associated with a higher risk of kidney function decline compared to TAF in treatment-naïve CHB patients[11](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR11 "Jung, C. Y., Kim, H. W., Ahn, S. H., Kim, S. U. & Kim, B. S. Higher risk of kidney function decline with Entecavir than Tenofovir Alafenamide in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 42, 1017–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.15208

(2022)."). Specifically, one study reported a faster rate of renal function decline in the ETV group compared to the TAF group. However, a major limitation of that study was its small sample size, with only 149 patients in each group. In contrast, our study, which utilized a much larger cohort from the Korean HIRA database, found no significant difference between ETV and TAF regarding CKD or ESRD incidence.While our study focused on comparing TAF and ETV as first-line agents recommended for patients at risk of renal dysfunction, we acknowledge that the exclusion of TDF may limit the broader clinical context of our findings. TDF has been extensively studied and is consistently associated with a higher risk of nephrotoxicity compared to both TAF and ETV. Large-scale East Asian cohort studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that long-term TDF use is linked to significantly greater declines in renal function and higher risks of chronic kidney disease (CKD). For example, a multicenter Asian cohort study (REAL-B) found that TDF was associated with a 26% higher hazard of renal function decline compared to ETV over a 5-year period.[12](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR12 "Mak, L. Y. et al. Longitudinal renal changes in chronic hepatitis B patients treated with Entecavir versus TDF: a REAL-B study. Hepatol. Int. 16, 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-021-10271-x

(2022).") _Similarly_, _a recent Korean national cohort study reported that TDF use resulted in a 1.76-fold higher risk of CKD progression compared to untreated controls_, _whereas no significant difference was observed between ETV or TAF and untreated patients._[5](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR5 "Hong, H. et al. Longitudinal changes in renal function in patients with chronic hepatitis B on antiviral treatment. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 59, 515–525.

https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.17819

(2024).") _Meta-analyses also confirm that TDF carries a higher nephrotoxicity risk than either TAF or ETV._[13](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR13 "Lee, H. Y. et al. Comparison of renal safety of Tenofovir and Entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B: systematic review with meta-analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 25, 2961–2972.

https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i23.2961

(2019)."),[14](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR14 "Liu, Z., Zhao, Z., Ma, X., Liu, S. & Xin, Y. Renal and bone side effects of long-term use of entecavir, Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and Tenofovir Alafenamide fumarate in patients with hepatitis B: a network meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 23, 384.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-03027-4

(2023).").Several hypotheses could explain the lack of significant differences in CKD or ESRD incidence between the TAF and ETV groups. Both TAF and ETV may have renal protective mechanisms that lead to similar outcomes. Although TAF is often preferred due to its lower nephrotoxicity compared to TDF, ETV may also possess properties that protect against renal decline, particularly when baseline renal function and other risk factors are controlled through PSM. Additionally, both antiviral agents are highly effective in suppressing HBV replication, which reduces inflammation and immune activation in the kidneys. This effective viral suppression may help mitigate HBV-related renal damage, leading to similar renal outcomes in patients treated with either drug.

Our study rigorously matched baseline characteristics to ensure comparability between the TAF and ETV groups. By balancing factors such as age, gender, comorbidities, and baseline renal function, we effectively minimized the influence of confounding variables. This rigorous matching may explain why, when baseline risk factors are similar, the choice between TAF and ETV does not significantly affect renal outcomes. Additionally, the duration of follow-up in this study may primarily capture short to intermediate-term renal outcomes. Differences in impact on renal function between TAF and ETV may become more apparent over a longer follow-up period. Long-term studies are necessary to identify subtle differences that may not be evident in a shorter timeframe. Patients with CHB might have varying degrees of underlying renal health that respond differently to antiviral treatments. Both TAF and ETV might be similarly tolerated in patients with relatively preserved renal function, leading to comparable outcomes in the incidence of CKD and ESRD.

TAF has been relatively recently introduced and is recognized for its safety in patients with impaired renal function, especially when compared to TDF. However, aside from the previously mentioned study involving 149 patients, there is a lack of direct comparative research data between TAF and ETV[11](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR11 "Jung, C. Y., Kim, H. W., Ahn, S. H., Kim, S. U. & Kim, B. S. Higher risk of kidney function decline with Entecavir than Tenofovir Alafenamide in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 42, 1017–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.15208

(2022)."). ETV’s impact on renal function has been more extensively studied compared to other antiviral agents such as TDF and telbivudine, with varying results reported across different studies. Some studies suggest that the impact of ETV and TDF on renal function is similar. Park et al.[15](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR15 "Park, J. et al. Effects of Entecavir and Tenofovir on renal function in patients with hepatitis B Virus-Related compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. Gut Liver. 11, 828–834.

https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl16484

(2017).") reported that there were no significant changes in estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR) from baseline in either the ETV- or TDF-treated groups at week 96\. Similarly, Trinh et al.[16](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR16 "Trinh, S. et al. Changes in Renal Function in Patients With Chronic HBV Infection Treated With Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate vs Entecavir. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 17, 948–956 e941, (2019).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.037

") found that TDF was not associated with a higher risk of worsening renal function during short- or intermediate-term follow-up periods among patients without significant renal impairment compared with ETV. Conversely, numerous reports suggest that ETV is more favorable than TDF for patients with declining renal function. A meta-analysis indicated that TDF has a more detrimental impact on renal function compared to ETV within a 24-month period[17](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR17 "Yang, X., Yan, H., Zhang, X., Qin, X. & Guo, P. Comparison of renal safety and bone mineral density of Tenofovir and Entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 124, 133–142.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.09.021

(2022)."). Furthermore, another study found no significant change in eGFR in the ETV group after an average of 44 months, while patients treated with TDF showed a decline in renal function[18](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR18 "Tsai, M. C. et al. Comparison of renal safety and efficacy of telbivudine, entecavir and tenofovir treatment in chronic hepatitis B patients: real world experience. Clin Microbiol Infect 22, 95 e91-95 e97, (2016).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2015.05.035

"). Additionally, ETV has been reported to be safe for patients undergoing dialysis with ESRD. One study showed that ETV is highly effective for HBV-infected patients with severe renal dysfunction, including those on hemodialysis, and it does not adversely affect renal function[19](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR19 "Suzuki, K. et al. Entecavir treatment of hepatitis B virus-infected patients with severe renal impairment and those on Hemodialysis. Hepatol. Res. 49, 1294–1304.

https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.13399

(2019)."). Conversely, a meta-analysis comparing ETV to telbivudine revealed that ETV use led to a decline in eGFR[20](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR20 "Wu, X. et al. Potential effects of Telbivudine and Entecavir on renal function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Virol. J. 13, 64.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-016-0522-6

(2016).")while eGFR improved with telbivudine[20](/articles/s41598-025-08023-0#ref-CR20 "Wu, X. et al. Potential effects of Telbivudine and Entecavir on renal function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Virol. J. 13, 64.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-016-0522-6

(2016)."). Based on our findings that TAF and ETV have similar impacts on the incidence of CKD and ESRD in patients with chronic hepatitis B, several areas for future research are suggested to build on and expand our understanding of these antiviral treatments.This study has several limitations. First, although we employed a rigorous propensity score matching approach to balance key covariates such as age, sex, comorbidities, and decompensated liver status, residual confounding cannot be completely ruled out. Notably, the absence of laboratory data, including baseline and serial serum creatinine, eGFR, proteinuria, and HBV DNA levels, limited our ability to precisely characterize renal function and virologic control. This may have led to misclassification of CKD status or delayed recognition of renal decline, potentially attenuating true differences between treatment groups. Additionally, unmeasured factors such as medication adherence, lifestyle habits (e.g., smoking, alcohol use), and socioeconomic status may have influenced renal outcomes but were not captured in the claims database. Second, our study relied on claims data from the HIRA, which, although comprehensive, has its limitations. The use of ICD-10 codes to identify CKD and ESRD may lead to misclassification or underreporting of these conditions. Third, the follow-up period in this study may not be sufficient to capture the full spectrum of long-term renal outcomes. CKD and ESRD can take many years to develop, and a longer follow-up period would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the renal safety profiles of TAF and ETV. The current follow-up period may primarily reflect short to intermediate-term outcomes, and longer-term studies are necessary to validate our findings. Finally, while propensity score matching helps balance observed covariates between the treatment groups, it cannot account for unmeasured or unknown confounders. Variables such as baseline nutritional status, socioeconomic factors, and access to healthcare services, which are not captured in claims data, could influence the outcomes.

An additional important consideration is the potential for physician selection bias in antiviral prescriptions. In Korea, ETV has been preferentially prescribed for patients with mild or suspected renal impairment, particularly in the early years of TAF availability. This practice may explain the higher pre-PSM incidence of CKD in the ETV group. Although our PSM approach balanced baseline risk factors, unmeasured clinical variables such as subclinical renal dysfunction or physician preference may still confound results. Future studies integrating laboratory data or prospective designs could further clarify this issue.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that, after adjusting for baseline differences, ETV and TAF have comparable effects on the incidence of CKD and ESRD in patients with chronic hepatitis B. These findings are important for clinicians making informed decisions about antiviral therapy, especially for patients at risk of renal dysfunction. Ongoing vigilance in monitoring renal function and further research are crucial to ensure the long-term safety and efficacy of antiviral treatments for this vulnerable population.

Materials and methods

Data source

The data from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) in South Korea were used for this study. The country’s universal healthcare system, which includes mandatory social health insurance, covers 98% of the population. Annually, around 46 million individuals file health insurance claims, representing 90% of registered residents. HIRA claims data, generated when healthcare providers submit claims for reimbursement or academic purposes, serves as a vital resource for healthcare service research. TAF was introduced for prescription in Korea following reimbursement certification in November 2017. This study focused on patients with chronic hepatitis B who had been prescribed either ETV or TAF since January 2018 and had no prior history of antiviral drugs use.

Study cohort

In this study, we assess the impact of TAF and ETV on CKD by forming and analyzing two distinct cohorts as follows.

Cohort 1: patients with normal renal function (outcome: CKD)

The incidence of CKD was analyzed in patients with normal renal function and no prior history of CKD. Inclusion criteria were treatment-naive chronic hepatitis B patients who were newly prescribed ETV or TAF after January 1, 2018. Exclusion criteria were: (1) a history of antiviral drug prescription before 2018, (2) use of antiviral drug other than TAF or ETV (combination treatment or change in antiviral drug), (3) co-infection with HCV or HIV, and (4) diagnosis of CKD prior to starting antiviral medication. A flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1a.

Cohort 2: patients with CKD (outcome: ESRD)

Given that patients with normal renal function rarely progress to ESRD during the observation period, the study also analyzed progression to ESRD especially in chronic hepatitis B patients with pre-existing CKD. Inclusion criteria were treatment-naive chronic hepatitis B patients with CKD, but without ESRD, who were newly prescribed ETV or TAF after January 1, 2018. Exclusion criteria were: (1) a history of antiviral drug prescription before 2018, (2) use of antiviral drug other than TAF or ETV (including combination treatment or change in antiviral drug), (3) co-infection with HCV or HIV, and (4) a diagnosis of ESRD prior to starting antiviral medication. A flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1b.

After applying these exclusions, the final analysis sample for cohort 1 (patients without CKD) included 60,178 individuals, with 28,486 receiving TAF and 31,692 receiving ETV. Cohort 2 (patients with CKD but without ESRD) comprised 2,236 individuals, with 677 receiving TAF and 1,559 receiving ETV. To ensure comparability between the TDF and TAF groups, a 1:1 PSM was conducted in both cohort 1 and cohort 2. This process resulted in 4,588 individuals in each group for cohort 1, and 339 individuals in each group for cohort 2 in the final analysis. The study protocol received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital (SCHBC 2023-07-016-001, date of registration: 23 September 2023) and adhered to the ethical guidelines outlined in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Definition of HBV, antiviral treatment, and outcome

Chronic hepatitis B was identified using ICD-10 codes B18.0 (Chronic viral hepatitis B with delta-agent) or B18.1 (Chronic viral hepatitis B without delta-agent, Hepatitis B (viral) NOS). Antiviral drug intake was determined using the Korea Drug Code, with TAF indicated by Korea Drug Code 665301ATB and ETV by Korea Drug Codes 487202ATB. The primary outcome of the study was the incidence of CKD in cohort 1 and the incidence of ESRD in cohort 2. CKD was defined as receiving outpatient or inpatient treatment more than twice with the ICD-10 code N18 (Chronic kidney disease) after initiating antiviral medication. ESRD was defined as receiving dialysis more than twice with the ICD-10 code N18.5 (Chronic kidney disease, stage 5) after initiating antiviral medication.

Statistical analysis

To minimize potential confounding variables and ensure balanced covariates between the two groups, we estimated propensity scores using factors that could influence CKD, including age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, antiviral treatment duration, cirrhosis, and decompensated status. PSM was then conducted at a 1:1 ratio between the TAF and the ETV prescription group. PSM was selected over IPTW to prioritize strict covariate balance and minimize the risk of extreme weights, given the substantial baseline differences and the nature of claims data. Survival probabilities over time were estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves, and differences between groups were assessed for statistical significance using the log-rank test. To identify factors influencing CKD occurrence, we calculated HR and 95% CI using a multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model. This model adjusted for potential confounders such as age, sex, comorbidities, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). Variables for the multivariable Cox regression models were selected based on both statistical significance in univariate analyses (p < 0.05) and clinical relevance, with the primary exposure variable ‘ETV’ included regardless of its univariate p-value.

In instances where the proportional hazards assumption was violated, alternative models such as the Poisson model were considered. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze variables, with frequencies and percentages reported for categorical variables. The chi-square test was used for categorical variables, while Student’s t-test was applied for continuous variables to examine relationships between them. We defined a 1-year washout period prior to 2018, and person-years (PY) were calculated from the date of the first antiviral prescription until the onset of CKD or ESRD. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS program version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Two-sided tests were used, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Kim, L. Y. et al. The epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in korea: 15-Year analysis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 39, e22. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e22 (2024).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kim, D. Y. Changing etiology and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: Asia and worldwide. J. Liver Cancer. 24, 62–70. https://doi.org/10.17998/jlc.2024.03.13 (2024).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jang, W. et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of Korean patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with respect to etiology. J. Liver Cancer. 22, 158–166. https://doi.org/10.17998/jlc.2022.09.18 (2022).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hsu, Y. C., Tseng, C. H. & Kao, J. H. Safety considerations for withdrawal of nucleos(t)ide analogues in patients with chronic hepatitis B: first, do no harm. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 29, 869–890. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2022.0420 (2023).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hong, H. et al. Longitudinal changes in renal function in patients with chronic hepatitis B on antiviral treatment. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 59, 515–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.17819 (2024).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jung, W. J. et al. Effect of Tenofovir on renal function in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Med. (Baltim). 97, e9756. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000009756 (2018).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jung, C. Y., Kim, H. W., Ahn, S. H., Kim, S. U. & Kim, B. S. Tenofovir is associated with higher risk of kidney function decline than Entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20 (e952), 956–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2021.05.032 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lee, H. A. & Seo, Y. S. Current knowledge about biomarkers of acute kidney injury in liver cirrhosis. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 28, 31–46. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2021.0148 (2022).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address, E. E. E. & European association for the study of the, L. EASL 2017 clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J. Hepatol. 67, 370–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021 (2017).

Article Google Scholar - Liang, L. Y. & Wong, G. L. Unmet need in chronic hepatitis B management. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 25, 172–180. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2018.0106 (2019).

Article MathSciNet PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jung, C. Y., Kim, H. W., Ahn, S. H., Kim, S. U. & Kim, B. S. Higher risk of kidney function decline with Entecavir than Tenofovir Alafenamide in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 42, 1017–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.15208 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mak, L. Y. et al. Longitudinal renal changes in chronic hepatitis B patients treated with Entecavir versus TDF: a REAL-B study. Hepatol. Int. 16, 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-021-10271-x (2022).

Article MathSciNet PubMed Google Scholar - Lee, H. Y. et al. Comparison of renal safety of Tenofovir and Entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B: systematic review with meta-analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 25, 2961–2972. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i23.2961 (2019).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Liu, Z., Zhao, Z., Ma, X., Liu, S. & Xin, Y. Renal and bone side effects of long-term use of entecavir, Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and Tenofovir Alafenamide fumarate in patients with hepatitis B: a network meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 23, 384. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-03027-4 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Park, J. et al. Effects of Entecavir and Tenofovir on renal function in patients with hepatitis B Virus-Related compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. Gut Liver. 11, 828–834. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl16484 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Trinh, S. et al. Changes in Renal Function in Patients With Chronic HBV Infection Treated With Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate vs Entecavir. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 17, 948–956 e941, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.037

- Yang, X., Yan, H., Zhang, X., Qin, X. & Guo, P. Comparison of renal safety and bone mineral density of Tenofovir and Entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 124, 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.09.021 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Tsai, M. C. et al. Comparison of renal safety and efficacy of telbivudine, entecavir and tenofovir treatment in chronic hepatitis B patients: real world experience. Clin Microbiol Infect 22, 95 e91-95 e97, (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2015.05.035

- Suzuki, K. et al. Entecavir treatment of hepatitis B virus-infected patients with severe renal impairment and those on Hemodialysis. Hepatol. Res. 49, 1294–1304. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.13399 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wu, X. et al. Potential effects of Telbivudine and Entecavir on renal function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Virol. J. 13, 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-016-0522-6 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital Hyangseol Research Fund 2023 and partly supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research fund.

Author information

Author notes

- Hyuk Kim MD and Jae Young Kim PhD contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

- Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, Bucheon, Republic of Korea

Hyuk Kim, Jeong-Ju Yoo, Sang Gyune Kim & Young-Seok Kim - Department of Internal Medicine, Soonchunhyang University School of Medicine, Cheonan, Republic of Korea

Jae Young Kim & Hye-Jin Yoo - Department of Big DATA Strategy, National Health Insurance Service, Wonju, Republic of Korea

Log Young Kim - Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, 170 Jomaruro Wonmigu, Bucheonsi, 14584, Gyeonggido, Republic of Korea

Jeong-Ju Yoo

Authors

- Hyuk Kim

- Jae Young Kim

- Hye-Jin Yoo

- Log Young Kim

- Jeong-Ju Yoo

- Sang Gyune Kim

- Young-Seok Kim

Contributions

H.K.: manuscript writing. J.Y.K.: provision of study materials or patients, collection and assembly of data. H-J.Y.: investigation. L.Y.K.: collection and assembly of data. J-J.Y.: study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing. S.G.K.: data analysis and interpretation. Y-S.K.: data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence toJeong-Ju Yoo.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests statement

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H., Kim, J.Y., Yoo, HJ. et al. Nationwide analysis of renal outcomes in chronic hepatitis B patients treated with Tenofovir Alafenamide vs. Entecavir.Sci Rep 15, 33872 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08023-0

- Received: 24 January 2025

- Accepted: 18 June 2025

- Published: 30 September 2025

- Version of record: 30 September 2025

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08023-0