Ciprofloxacin induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation of human colorectal carcinoma cells (original) (raw)

Main

Cancers of the colon and rectum are the most common gastrointestinal neoplasms, with an incidence of about 44 per 100 000 per year (Boyle and Langman, 2000; Ries et al, 2000). Prognosis and therapy are determined by tumour stage, as reflected by the TNM- or the Dukes-classification, the involvement of lymph nodes and the presence of metastases. Operated patients with lesions restricted to the mucosa and submucosa (Dukes A or T1N0M0) have a 90% 5-year-survival, whereas prognosis of patients with advanced stages of the disease (Dukes D or T1N0M0) is poor. The first-line treatment is radical surgical resection with local lymph node dissection. In advanced stages of the disease, the effect of palliative chemotherapy is limited (Midgley and Kerr, 1999; Young and Rea, 2000).

It was recently shown that the fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin, a commonly used broad-spectrum antibiotic with low side effects, can induce time- and dose-dependent growth inhibition and apoptosis of bladder carcinoma (Seay et al, 1996; Ebisuno et al, 1997; Aranha et al, 2000), osteosarcoma (Miclau et al, 1998) and leukaemia cell lines (Some et al, 1989). Fluoroquinolone antibiotics inhibit the bacterial type II topoisomerase/DNA gyrase which is responsible for supercoiling, transcription, replication and chromosomal separation of prokaryotic DNA (Chen and Liu, 1994). How fluoroquinolone antibiotics might affect mammalian cells is still unclear. There are no data on the effects of fluoroquinolone antibiotics on human colon carcinoma cell proliferation and apoptosis. We therefore investigated the anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of ciprofloxacin on the colon carcinoma cell lines CC-531, SW-403 and HT-29.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

CC-531 cells (rat, colorectal cancer, established from a thioacetamide-induced colon carcinoma) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) with 10% foetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco–BRL, Karlsruhe, Germany), penicillin (100 U l−1), streptomycin (10 mg l−1) and ascorbic acid (50 mg l−1) at 37°C and 5% CO2. HT-29 cells (human colorectal cancer, well differentiated) were cultured in the same medium without ascorbic acid. SW-403 (human colorectal cancer, established from a low differentiated tumour) and HepG2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's MEM (Biochrom) with the same additives (except ascorbic acid) and under the same conditions. All cell lines were obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (Braunschweig, Germany). Cells were starved for 24 h in medium containing 0.125% FCS, trypsinized (0.05% Trypsin, 0.02% EDTA, Biochrom), seeded at a density of 0.5 × 106 per well in six-well plates (9 cm2) (Becton Dickinson, Mannheim, Germany) or at a density of 5 × 103 per well in 96-well plates (1 cm2) and incubated with 100, 200 or 500 μg ml−1 ciprofloxacin (concentration according to Aranha et al, 2000). Ciprofloxacin, which was friendly provided by Bayer (Leverkusen, Germany) was dissolved in water and further diluted in culture medium. If not otherwise mentioned, for collection of cells supernatants were saved after 18, 24, 48 or 72 h of incubation and centrifuged together with the trypsinized cells (1000 r.p.m. for 10 min). Further procession is described below.

Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis

Cell death was measured by lysing cells in a hypotonic solution containing 0.1% sodium citrate, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 50 μg ml−1 propidium iodide (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) after two washes with PBS and Trypsin-EDTA solution. Analysis of the labelled nuclei was performed on a FACSCalibur fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) using CELLQuest software (both from Becton Dickinson). The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by measuring the fraction of nuclei that contained a sub-diploid DNA content. Ten thousand events were collected for each sample analyzed.

BrdU-Incorporation ELISA

DNA-synthesis, which correlates well with cellular proliferation, was measured by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation using the Cell Proliferation ELISA (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) based on incorporation of BrdU into newly synthesized DNA and antibody-mediated detection of BrdU in DNA as described (Ruehl et al, 1999). Briefly, 5 × 103 cells were seeded into 96-well microtiter plates (Falcon) and incubated with culture medium containing 10% FCS. BrdU was added to the cells together with CIP (10−3–10−5M). After 24 h cells were fixed and DNA denatured with an ethanolic solution (30 min), followed by incubation with an antibody to BrdU conjugated with peroxidase (60 min, 37°C). Immune complexes were detected using tetramethylbenzidine as substrate for 5 min, the reaction was stopped with H2SO4 and absorption measured at 450 nm in an ELISA reader (MRX II, Dynex, Frankfurt, Germany). The results are given as BrdU-incorporation (%) compared to untreated cells.

Analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential

Mitochondrial injury was assessed by JC-1 staining (MoBiTec, Goettingen, Germany). This dye, existing as a monomer in solution emitting a green fluorescence, can assume a dimeric configuration emitting red fluorescence in a reaction driven by the mitochondrial transmembrane potential (Lawrence et al, 1993; Loeffler and Kroemer, 2000). Thus, red fluorescence of JC-1 indicates intact mitochondria, whereas green fluorescence shows monomeric JC-1 that remained unprocessed due to breakdown of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Reers et al, 1991). After trypsinization and centrifugation (RT, 10 min, 800 r.p.m.) the cell pellet resuspended in 1 ml medium, stained with 5 μg ml−1 JC-1 for 15 min at 37°C in the dark, then washed twice in PBS and resuspended in 0.5 ml PBS. Analysis was performed by FACS scan and mitochondrial function was assessed as JC-1 green (uncoupled mitochondria) or red (intact mitochondria) fluorescence (Smiley et al, 1991).

Assessment of caspase activity

Caspase Colorimetric Assays (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, WI, USA) were used to determine the enzymatic activity of caspases 3, 8 and 9. The assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions after a 24 h incubation with increasing concentrations of ciprofloxacin. Caspase activation leads to the cleavage of the provided colorimetric substrates (all substrate peptides are conjugated to p-nitroaniline (pNA); caspase 3: DEVD-pNA, caspase 8: IETD-pNA, caspase 9: LEHD-pNA) and can be measured photometrically at 405 nm. According to the manufacturer and previous publications (Sanghavi et al, 1998; Dudich et al, 2000; Li et al, 2001) these amino acid sequences are the preferred ones of each caspase.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed by adding 100 μl 2 × sample buffer (2 mM NEM, 2 mM PMSF, 4% SDS, 4% DTT, 20% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue, 2 M urea, 0.01 M Na-EDTA, 0.15 M Tris-HCl) to 106 cells. DNA was sheared by pipetting up and down for 3 min at room temperature and suspensions were boiled at 95°C for 15 min, centrifuged at 13 000 r.p.m. for 10 min and subjected to 14% SDS–PAGE (pre-cast gels, Novex, San Diego, CA, USA). After blocking overnight at room temperature in a buffer containing PBS, 0.1% Tween 20 and 4% low fat milk powder, nitrocellulose membranes were incubated for 90 min either with polyclonal rabbit antibodies to human Bcl-2 (1:400, sc-783) or to human Bax (1:500, sc-493, both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Membranes were washed three times for 10 min in a buffer containing PBS, 0.1% Tween 20 and 4% low fat milk powder and incubated with a goat anti-rabbit IgG coupled to peroxidase (1:1000, Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) for 1 h at room temperature. Reactive bands were detected with the ECL chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) and band intensities were analyzed by densitometry. Normalization was performed to β-actin.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows (Release 9.0.0; SPSS Inc Chicago IL, USA). Significances were calculated using the _t_-test for paired samples P<0.05 was regarded as significant, P<0.01 as highly significant.

Results

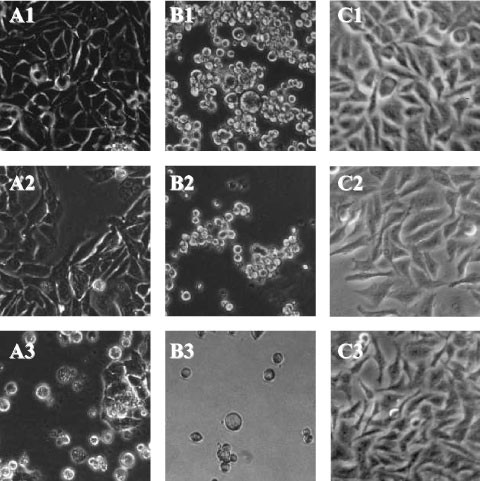

Morphological changes induced by ciprofloxacin

Figure 1 shows morphological changes observed in CC-531, SW-403 and HT-29 cells after incubation with different concentrations of ciprofloxacin for 18 h. While untreated cells grew adherent on culture plates and were of a slender and spindle-shaped appearance, cells cultured with ciprofloxacin detached from their substratum, became rounded and pyknotic and showed apoptotic bodies, thus displaying the typical morphological changes for apoptotic cells. The control cell line HepG2 did not show comparable morphological changes.

Figure 1

Ciprofloxacin induces morphological signs of apoptosis in colon cancer cell lines. Colon cancer cells CC-531 (A) and SW-403 (B) as well as hepatoma cells HepG2 (C) untreated (1) and after 18 h of incubation with 100 μg ml−1 (2) and 500 μg ml−1 (3) of ciprofloxacin.

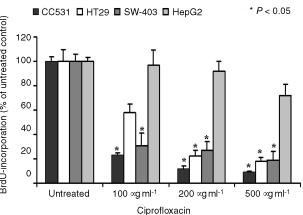

Ciprofloxacin inhibits colon carcinoma cell DNA synthesis

In CC-531 cells, incubation with ciprofloxacin at 100, 200 and 500 μg ml−1 for 24 h decreased the amount of BrdU incorporated into newly synthesized DNA from 100 to 23, 12 and 9%, respectively. Similar results were obtained for SW-403 and HT-29 cells. There was no antiproliferative effect of ciprofloxacin on HepG2 cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Ciprofloxacin inhibits DNA-synthesis in colon carcinoma cells. DNA-synthesis was measured by BrdU-incorporation in CC-531, HT-29, SW-403 and HepG2 hepatoma cells after treatment with 100, 200 or 500 μg ml−1 ciprofloxacin (24 h). Results for untreated cells were set at 100%. Values are means±s.d. of six independent experiments.

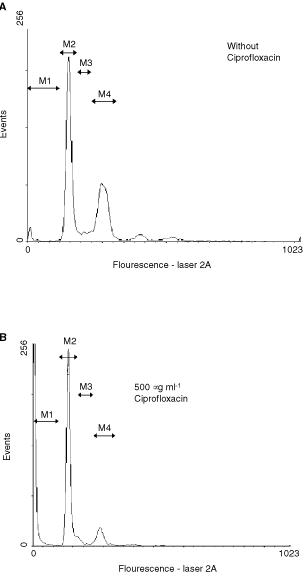

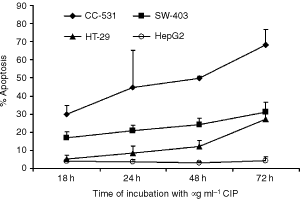

Ciprofloxacin induces cell death in human colon carcinoma cell lines via cell cycle arrest and mitochondrial membrane breakdown

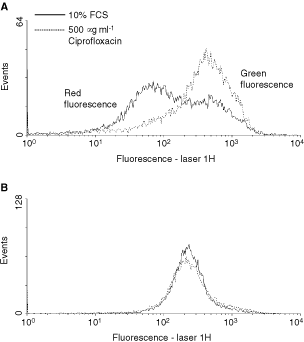

As evidenced by FACS-analysis of the cell cycle, ciprofloxacin lead to a decrease of the G2-peak and an increase of sub-G1 events (correlates with apoptosis) (Figure 3). Time- and dose-dependent induction of apoptosis were observed in CC-531 and HT-29 cells, while in SW-403 cells only doses of 200 and 500 μg ml−1 ciprofloxacin could induce significant rates of apoptosis after 18, 24, 48 and 72 h. In contrast, HepG2 cells remained largely unaffected (Table 1, Figure 4). While FACS analysis after staining with propidium iodide only visualizes the cell cycle, analysis after staining with JC-1 reveals the breakdown of mitochondrial membrane potential, which is known to be a key process during mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis. In fact, Figure 5 shows the increase in green vs red fluorescence, indicating increased mitochondrial breakdown in CC-531 but not HepG2 cells after 48 h of treatment with 500 μg ml−1 ciprofloxacin. For HT-29 and SW-403 cells similar data were obtained (not shown), while in HepG2 cells emitted fluorescence did not change after treatment with CIP (Figure 5). Experiments using different concentrations of CIP and different incubation periods showed fluorescent shift in a time- and dose-dependent manner.

Figure 3

Apoptosis is induced after 24 h of incubation with ciprofloxacin. When compared to untreated control cells (A), incubation of SW-403 cells with 500 μg ml−1 (B) for 24 h caused a decrease of S/G2-cells (M3 and M4) and an increase of sub-G1-cells (M1) M2 marks cells in G1 phase.

Table 1 Percentage of apoptotic cells after treatment with different concentrations of ciprofloxacin for 18, 24, 48 and 72 h

Figure 4

The Ciprofloxacin effect on apoptosis induction of colon cancer cells is time-dependent. Apoptosis rates were measured using FACS analysis. Results are given as means±s.d. of at least three independent experiments.

Figure 5

Ciprofloxacin induces mitochondrial injury of CC-531 (A) and HepG2 (B) cells. Green fluorescence of JC-1 dye was assessed as a parameter for mitochondrial breakdown. Increased green fluorescence is detectable in CC-531 cells incubated with 500 μg ml−1 ciprofloxacin for 48 h (dotted line) compared to cells treated with 10% FCS alone (black line) but not in HepG2 controls.

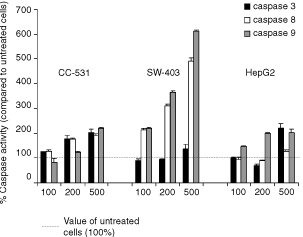

Ciprofloxacin activates caspases 3, 8 and 9

The basal activity of caspases was set to 100% in untreated cells and was measured after 24 h incubation with different concentrations of ciprofloxacin. The activity of caspase 3 increased significantly only in CC-531 cells after incuabtion with 200 or 500 μg ml−1 CIP, while no significant change was found in SW-403 cells and only after incubation with 500 μg ml−1 in HepG2 cells (Figure 6). Activation of caspases 8 and 9 was dose-dependent, with highest values after incubation with 500 μg ml−1 CIP (in SW-403 cells). In CC-531 cells caspase-8 activity doubled after incubation with 200 and 500 μg ml−1, while in SW403 cell comparable results were induced even by 100 μg ml−1 CIP. Caspase 9 activity increased even more distinctly in SW-403 cells, while in CC-531 cells only the highest dose lead to significant caspase 9 activation. In HepG2 cells there was no change of caspase 8 activity, but doubled activation of caspase 9 after incubation with ⩾200 μg ml−1 (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Different caspases are activated after incubation with ciprofloxacin. Activity of caspase 3, 8 and 9 was measured by a colourimetric peptide substrate-cleavage ELISA. Cells were treated with 100, 200 or 500 μg ml−1 ciprofloxacin (24 h). Basal activity of untreated cells was set at 100%. Values are means±s.d. of five independent experiments. Dotted line –––: value for untreated cells.

Pro-apoptotic Bax is upregulated by ciprofloxacin

Semi-quantitative Western blots were performed to investigate the effect of ciprofloxacin on pro-apoptotic Bax and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2. The ratio of Bax: Bcl-2 was set at 1.0 in untreated cells. Bax increased dose-dependently after 3 h of incubation in all tested cell lines, while Bcl-2 remained unchanged during the observation time. Whereas in CC-531 cells the Bax: Bcl-2 ratio increased to 1.6, 2.3 and 5.1 with 100, 200 and 500 μg ml−1 ciprofloxacin, respectively, only a minor response was found for SW-403 and HepG2 cells. After 18 h, however, the Bax: Bcl-2 ratio remained close to baseline in HepG2 cells, whereas it was highly increased in both CC cell lines (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Ciprofloxacin increases the Bax: Bcl-2 ratio time-depently in colon cancer cells. Values of untreated cells were set to 1. Representative Western blot showing the increase of Bax and decrease of Bcl-2 expression in CC-531 and SW-403 cells.

Discussion

We showed that exposure of CC-531, HT-29 and SW-403 colon carcinoma cells to ciprofloxacin caused a rapid suppression of de novo DNA synthesis. Furthermore, ciprofloxacin potently induced dose- and time-dependent apoptosis as shown by cell cycle analysis and breakdown of the mitochondrial potential. In contrast, ciprofloxacin had no or little effect on proliferation or apoptosis in the hepatoma cell line HepG2.

Although it is assumed that fluoroquinolones only inhibit bacterial type II DNA topoisomerase/gyrase, our results confirm that they can affect the growth of certain eukaryotic cells as well. We and others hypothesize, that these effects occur possibly via unselective inhibition of mitochondrial DNA-synthesis with subsequent mitochondrial injury (Lawrence et al, 1993). Thus, topoisomerase inhibitors might induce a selective loss of mitochondrial DNA, finally leading to depletion of intracellular ATP stores. Energy depletion favours apoptosis via induction of cell cycle arrest at the S/G2-M checkpoint, with concomitant down-regulation of cyclin B, cyclin E, dephosphorylation of cdk2, and an up-regulation of pro-apoptotic Bax (Jurgensmeier et al, 1998; Bratton et al, 2000). Therefore, we especially investigated the mitochondrial-dependent events during apoptosis, such as breakdown of mitochondrial membrane, expression of Bax and Bcl-2 and activation of caspase 9. In fact, we observed a breakdown of the mitochondrial membrane potential, which is most probably followed by release of cytochrome c into the cytosol, its interaction with CED-4 like protein Apaf-1 (Smiley et al, 1991; Jurgensmeier et al, 1998; Bratton et al, 2000). The CED-4-cytochrome complex activates pro-caspase 9 and initiates a proteolytic cascade finally leading to apoptosis (Smiley et al, 1991; Mancini et al, 1997; Jurgensmeier et al, 1998). Fluoroquinolone antibiotics may also trigger the Bax-pathway of apoptosis or interfere directly with mitochondrial membrane proteins, as described for cyclosporin A that binds to the mitochondrial megapore (Mancini et al, 1997; Jurgensmeier et al, 1998). Thus, activation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore by Bax with subsequent release of cytochrome c has been described (Marzo et al, 1998, Narita et al, 1998). The ability of ciprofloxacin to activate Bax was recently shown in a bladder carcinoma cell line (Aranha et al, 2000). Here, we observed that ciprofloxacin mediates an up-regulation of Bax. Expression of Bcl-2, which remained unchanged in our experiments, inhibits apoptosis possibly via prevention of oxidative damage to subcellular components (Kroemer, 1997) and reduces caspase activity by preventing the formation of pro-apoptotic bodies (Zhang et al, 1999).

Caspase 3 is activated during the process of apoptosis and is one of the key enzymes required for the execution of the apoptotic programme. Caspase 8 (the major caspase to be activated by the TNF pathway) and caspase 9 (mitochondrial pathway) are initiator-caspases activating the downstream effector-caspases, especially caspase 3. Our results show significant changes of caspase 8 and 9 in all colorectal cancer cell lines, while caspase 3 was increased significantly only in CC-531 cells. All changes appeared to be dose-dependent. The observation of a well-balanced caspase activation profile in CC-531 cells and the distinctly higher activation of the initiator caspases vs caspase 3 in SW-403 cells appear to be related to a different progression of apoptosis. Thus, after 24 h of incubation with CIP, the apoptosis rates – as shown by FACS analysis – are higher in CC-531 than in SW-403 cells. Our results of an increase in caspase 8 and 9 demonstrate that CIP induces the membrane-related as well as the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Similarly, hypoxia can stimulate both apoptosis pathways in lymphoma cells (Malrhota et al, 2001). Our results of elevated bax and mitochondrial membrane potential breakdown further indicates the CIP may primarily mediate breakdown of mitochondrial membrane potential, while Caspase 8 is secondarily activated. However, this needs further evaluation by using caspase inhibitors.

In summary, we show that ciprofloxacin induces growth inhibition and apoptosis in colon carcinoma cell lines in a time- and dose-dependent manner, whereas hepatoma cells remained unaffected. The growth arrest is mediated through inhibition of DNA-synthesis, induction of mitochondrial injury and subsequent apoptosis. CIP can reach concentrations far above those of the serum in solid tissues, such as the lung. Therefore, due to the encouraging effects of this topoisomerase inhibitor CIP as well as other fluoroquinolones should be further investigated as (adjunctive) anti-tumoural agents in colorectal cancer cells.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

- Aranha O, Wood Jr DP & Sarkar FH (2000) Ciprofloxacin mediated cell growth inhibition, S/G2-M cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis in a human transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder cell line. Clin Cancer Res 6: 891–900

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Boyle P & Langman JS (2000) ABC of colorectal cancer: Epidemiology. Br Med J 321: 805–808

Article CAS Google Scholar - Bratton SB, MacFarlane M, Cain K & Cohen GM (2000) Protein complexes activate distinct caspase cascades in death receptor and stress-induced apoptosis. Exp Cell Res 256: 27–33

Article CAS Google Scholar - Chen AY & Liu LF (1994) DNA topoisomerases: essential enzymes and lethal targets. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 34: 191–218

Article CAS Google Scholar - Dudich E, Semenkova L, Dudich I, Gorbatova E, Tochtamisheva N, Tatulov E, Nikolaeva M & Sukhikh G (1999) Alpha-fetoprotein causes apoptosis in tumor cells via a pathway independent of CD95, TNFR1 and TNFR2 through activation of caspase-3-like proteases. Eur J Biochem 266: 750–761

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ebisuno S, Inagaki T, Kohjimoto Y & Ohkawa T (1997) The cytotoxic effect of fleroxacin and ciprofloxacin on transitional cell carcinoma in vitro. Cancer 80: 2263–2267

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jurgensmeier JM, Xie Z, Deveraux Q, Ellerby L, Bredesen D & Reed JC (1998) Bax directly induces release of cytochrome c from isolated mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 4997–5002

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kroemer G (1997) The proto-oncogene Bcl-2 and its role in regulating apoptosis. Nat Med 3: 614–620

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lawrence JW, Darkin-Rattray S, Xie F, Neims AH & Rowe TC (1993) 4-quinolones cause a selective loss of mitochondrial DNA from mouse L1210 leukemia cells. J Cell Biochem 51: 165–174

Article CAS Google Scholar - Li M, Wu X & Xu XC (2001) Induction of apoptosis in colon cancer cells by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor NS398 through a cytochrome _c_-dependent pathway. Clin Cancer Res 7: 1010–1016

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Loeffler M & Kroemer G (2000) The mitochondrion in cell death control: certainties and incognita. Exp Cell Res 256: 19–26

Article CAS Google Scholar - Malrhota R, Lin Z, Vincenz C & Brosius III FC (2001) Hypoxia induces apoptosis via tow independent pathways in Jurkat cells: differential regulation by glucose. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: 1596–1603

Article Google Scholar - Mancini M, Anderson BO, Caldwell E, Sedghinasab M, Paty PB & Hockenbery DM (1997) Mitochondrial proliferation and paradoxical membrane depolarization during terminal differentiation and apoptosis in a human colon carcinoma cell line. J Cell Biol 138: 449–469

Article CAS Google Scholar - Marzo I, Brenner C, Zamzami N, Jurgensmeier JM, Susin SA, Vieira HL, Prevost MC, Xie Z, Matsuyama S, Reed JC & Kroemer G (1998) Bax and adenine nucleotide translocator cooperate in the mitochondrial control of apoptosis. Science 281: 2027–2031

Article CAS Google Scholar - Miclau T, Edin ML, Lester GE, Lindsey RW & Dahners LE (1998) Effect of ciprofloxacin on the proliferation of osteoblast-like MG-63 human osteosarcoma cells in vitro. J Orthop Res 16: 509–512

Article CAS Google Scholar - Midgley RS & Kerr DJ (1999) Colorectal cancer. Lancet 353: 391–399

Article CAS Google Scholar - Narita M, Shimizu S, Ito T, Chittenden T, Lutz RJ, Matsuda H & Tsujimoto Y (1998) Bax interacts with the permeability transition pore to induce permeability transition and cytochrome c release in isolated mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 14681–14686

Article CAS Google Scholar - Reers M, Smith TW & Chen LB (1991) J-aggregate formation of a carbocyanine as a quantitative fluorescent indicator of membrane potential. Biochemistry 30: 4480–4486

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ries LA, Wingo PA, Miller DS, Howe HL, Weir HK, Rosenberg HM, Vernon SW, Cronin K & Edwards BK (2000) The annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1997, with a special section on colorectal cancer. Cancer 88: 2398–2424

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ruehl M, Sahin E, Johannsen M, Manski D, Riecken EO & Schuppan D (1999) Soluble collagen VI drives serum-starved fibroblasts through S phase and prevents apoptosis via down-regulation of Bax. J Biol Chem 274: 34361–34368

Article Google Scholar - Sanghavi DM, Thelen M, Thornberry NA, Casciola-Rosen L & Rosen A (1998) Caspase-mediated proteolysis during apoptosis: insights from apoptotic neutrophils. FEBS Lett 422: 179–184

Article CAS Google Scholar - Seay TM, Peretsman SJ & Dixon PS (1996) Inhibition of human transitional cell carcinoma in vitro proliferation by fluoroquinolone antibiotics. J Urol 155: 757–762

Article CAS Google Scholar - Smiley ST, Reers M, Mottola-Hartshorn C, Lin M, Chen A, Smith TW, Steele Jr GD & Chen LB (1991) Intracellular heterogeneity in mitochondrial membrane potentials revealed by a J-aggregate-forming lipophilic cation JC-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 3671–3675

Article CAS Google Scholar - Some E, Douer D, Shaked N & Rubinstein E (1989) In vitro effects of ciprofloxacin and pefloxacin on growth of normal human hematopoietic progenitor cells and on leukemic cell lines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 248: 415–418

Google Scholar - Young A & Rea D (2000) ABC of colorectal cancer: Treatment of advanced disease. Br Med J 321: 1278–1281

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zhang J, Reedy MC, Hannun YA & Obeid LM (1999) Inhibition of caspases inhibits the release of apoptotic bodies: Bcl-2 inhibits the initiation of formation of apoptotic bodies in chemotherapeutic agent-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol 145: 99–108

Article CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Dr. Hans-Martin Jäck and Wolfgang Schuh from the Department of Molecular Immunology at the Department of Internal Medicine III for their help with FACS-analysis. This work was supported by grants from the ELAN-Program (Fund for Research and Teaching, University of Erlangen-Nuernberg) and the German Cancer Aid Fund.

Author information

Author notes

- C Herold and M Ocker: Both authors contributed equally to this work

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Medicine I, University of Erlangen-Nuernberg, Krankenhausstr. 12, Erlangen, D-91054, Germany

C Herold, M Ocker, M Ganslmayer, H Gerauer, E G Hahn & D Schuppan

Authors

- C Herold

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - M Ocker

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - M Ganslmayer

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - H Gerauer

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - E G Hahn

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - D Schuppan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence toD Schuppan.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Herold, C., Ocker, M., Ganslmayer, M. et al. Ciprofloxacin induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation of human colorectal carcinoma cells.Br J Cancer 86, 443–448 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6600079

- Received: 31 July 2001

- Revised: 09 November 2001

- Accepted: 12 November 2001

- Published: 11 February 2002

- Issue Date: 01 February 2002

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6600079