T‐cell factor 4 (Tcf7l2) maintains proliferative compartments in zebrafish intestine (original) (raw)

Abstract

Previous studies have shown that Wnt signals, relayed through β‐catenin and T‐cell factor 4 (Tcf4), are essential for the induction and maintenance of crypts in mice. We have now generated a tcf4 (tcf7l2) mutant zebrafish by reverse genetics. We first observe a phenotypic defect at 4 weeks post‐fertilization (wpf), leading to death at about 6 wpf. The phenotype comprises a loss of proliferation at the base of the intestinal folds of the middle and distal parts of the intestine. The proximal intestine represents an independent compartment, as it expresses sox2 in the epithelium and barx1 in the surrounding mesenchyme, which are early stomach markers in higher vertebrates. Zebrafish are functionally stomach‐less, but the proximal intestine might share its ontogeny with the mammalian stomach. Rare adult homozygous tcf4 −/− ‘escapers’ show proliferation defects in the gut epithelium, but have no other obvious abnormalities. This study underscores the involvement of Tcf4 in maintaining proliferative self‐renewal in the intestine throughout life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Digestive Tract

Chapter © 2022

Introduction

Wnt signalling controls cell‐fate decisions in a wide variety of developmental processes and also in the maintenance of self‐renewing adult tissues (Clevers, 2006). Members of the T‐cell factor (Tcf)/Lef transcription factor family are downstream effectors of the Wnt cascade because they form nuclear complexes with β‐catenin on Wnt signalling (Behrens et al, 1996; Molenaar et al, 1996; van de Wetering et al, 1997). In these complexes, β‐catenin provides an essential transactivation domain, through which the complex activates its target genes. In the absence of Wnt ligands, Tcf proteins act as transcriptional repressors by establishing a complex with Groucho family members (Roose et al, 1998).

The vertebrate Tcf family of transcription factors consists of four members: Tcf1, Lef1, Tcf3 and Tcf4. Mammalian Tcf4 (Tcf7l2) is highly expressed in the midbrain and in intestinal and mammary epithelium (Cho & Dressler, 1998; Korinek et al, 1998a; Barker et al, 1999). In the developing gut, the expression of Tcf4 is first observed in the hindgut at 8.5 days post coitum (dpc; Gregorieff et al, 2004). In late embryonic and early neonatal gut, Tcf4 is present in the proliferative intervillus pockets (Barker et al, 1999). Tcf4 is essential for maintenance of the progenitor compartment of gut epithelium, as demonstrated in Tcf4‐deficient mice (Korinek et al, 1998b). As Tcf4 mutant mice die at birth, it is unknown whether this function of Tcf4 is required throughout life. The observed phenotype is restricted to the small intestine and the proximal half of the colon. The proliferative compartments of the other parts of the intestinal tract, that is, the oesophagus, the stomach and the distal colon, are unaffected.

The expression of the zebrafish tcf4 gene during embryogenesis in the anterior midbrain (Young et al, 2002) is strikingly similar to what has been reported for early mouse development (Korinek et al, 1997; Cho & Dressler, 1998). Moreover, the transient expression of zebrafish tcf4 in rhombomeres 4 and 5 at 48 hours post‐fertilization (hpf; Young et al, 2002) is also observed in the mouse hindbrain between 7.5 and 8.5 dpc (Cho & Dressler, 1998). From 72 hpf onwards, zebrafish tcf4 is also expressed in the developing gut (Young et al, 2002), coinciding with the onset of gut morphogenesis (Wallace & Pack, 2003; Ng et al, 2005). The similarity in the expression patterns of the mouse and zebrafish tcf4 genes, together with the growing validation of the zebrafish gut as a model system (Wallace & Pack, 2003; Crosnier et al, 2005; Haramis et al, 2006), led us to generate a genetic mutant by using target selected gene inactivation.

Results And Discussion

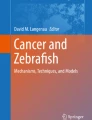

The zebrafish genome contains a single tcf4 orthologue (Young et al, 2002). We screened an _N_‐ethyl‐_N_‐nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenized zebrafish library for tcf4 mutations. A single mutant was identified which carried a Gly‐to‐Ala substitution within the splice donor site of intron 1 (Fig 1A). The mutation was predicted to lead to intron retention and to produce a very short truncated protein. Indeed, by reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR) analysis we failed to observe any correctly spliced exon 1–exon 2 sequences in mutant embryos (Fig 1A–D). Western blot analyses using an antibody detecting the amino‐terminal β‐catenin binding site encoded by the first exon confirmed the absence of Tcf4 protein (Fig 1E). Together, these experiments indicate that the mutant represents a null allele.

Figure 1

Analysis of splice/donor mutation in the zebrafish tcf4 gene, showing poor survival and slower growth rate in _tcf4_exI/exI fish. (A) Diagram of the _tcf4_exI/exI allele. The arrowhead points to nucleic acid substitution in the donor splice site of the first intron. The position of a stop codon within the first intron is underlined. Positions and PCR products of primer sets F1/R1 and F2/R2 are indicated. Note that primer R2 overlaps the exon I/exon II boundary. (B) RT–PCR preformed on complementary DNA samples from 7 dpf embryos with the primer set F1/R1. Heterozygous tcf4 cDNA (_tcf4_exI/wt) yields two bands (lane 2). The upper mutant band contains the retained intron. _tcf4_wt/wt (lane 3); _tcf4_exI/exI (lane 1). (C) RT–PCR of adult homozygous ‘escapers’ with the primer set F1/R1 (lane 2). In mutant ‘escapers’, only the upper band in which the intron is retained is present. Heterozygous (lane 1); wild‐type (wt; lane 3). (D) RT–PCR using the primer combination F2/R2. No wt band can be amplified in either tcf4exI/exI embryos (lane 1) or adult mutant escapers (lane 2). The same primer set detects only the wt band in heterozygous fish (lane 3). cDNA from wt fish (lane 4). (E) Western blot analysis of Tcf4 protein on 7 dpf _tcf4_exI/exI (right lane) or _tcf4_wt/wt (left lane) larvae. (F) Survival of the _tcf4_exI/exI genotype (black bars) in time (weeks). The _tcf4_exI/exI genotype is significantly lost first at 6 wpf. White bars represent the genotype frequency of wild types (_tcf4_wt/wt) and grey bars that of heterozygotes (_tcf4_exI/wt). (G) Body length of _tcf4_wt/wt and _tcf4_exI/exI fish monitored weekly. Mutant fish grow slower after 3 wpf. Data are percentages (F) or mean±s.d. (G). See Methods. All reference to phenotypes was confirmed by genotyping (see Methods). dpf, days post‐fertilization; RT–PCR, reverse transcription–PCR; Tcf4, T‐cell factor 4; wpf, weeks post‐fertilization.

Homozygous Tcf4 mutant (_tcf4_exI/exI) fish were viable and developed normally during the first weeks of life. We monitored the survival rate of Tcf4 mutants by genotyping weekly the offspring of heterozygous fish from several clutches (Fig 1F). Simultaneously, we measured the length of mutant and control fish (Fig 1G). This showed the loss of homozygous _tcf4_exI/exI larvae around 6 wpf (Fig 1F). Body length analysis showed linear growth during the first 3 weeks of wild‐type larval life (Fig 1G). From 4 wpf, the body length of wild‐type fish increased exponentially. The _Tcf4_exI/exI fish grew at the same linear rate during the first 3 weeks, but then failed to undergo the exponential growth phase observed in siblings (Fig 1G). The difference in body length was first noticeable at 4 wpf (Fig 1G). At 6 wpf, only 4 out of 85 live genotyped fish were of the homozygous mutant genotype (Fig 1F). We initiated histological analysis of mutants at this stage.

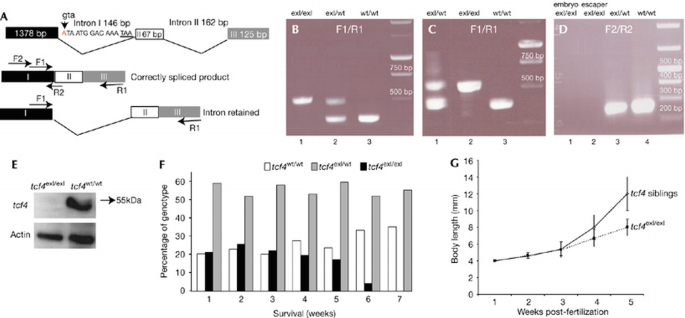

Genotyped 6‐week‐old _tcf4_exI/exI fish showed a single phenotypic abnormality. A striking lack of intestinal folds was observed in the middle and distal intestine (Fig 2C, lower panel). No morphological changes occurred in the proximal part of the intestine (Fig 2C, middle panel). The intestine of the wild‐type siblings harboured extensive epithelial folds (Fig 2A).

Figure 2

The absence of cycling cells in _tcf4_exI/exI at 6 weeks post‐fertilization. (A) Haematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of _tcf4_wt/wt zebrafish intestine with the proximal (Prox), middle (Mid) and distal (Dis) parts magnified respectively in lower panels. (B) PCNA staining on consecutive paraffin sections of wild‐type (wt) fish. The arrows in the magnified lower panels indicate PCNA+ cells in the interfold pockets. (C) HE staining of _tcf4_exI/exI intestine. (D) PCNA staining on consecutive sections depicting absent proliferation in the middle and distal intestinal portions. Note that proliferation in the proximal intestine is maintained (arrows and arrowheads in the magnified proximal intestine in (D)). PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; wpf, weeks post‐fertilization. Scale bars: top panels (A–D), 250 μm; middle and bottom panels (A–D), 50 μm.

In fish, proliferation is restricted to pockets at the base of the epithelial folds (Ng et al, 2005; Wallace et al, 2005), the equivalents to the mammalian crypts of Lieberkuhn. Almost no proliferation was observed in the hypoplastic areas in the middle and distal intestine by proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) stain (Fig 2D, bottom panel). Of note, unlike in Tcf4 mutant mice, the proximal part of the intestine retained proliferative cells (Fig 2D, bottom panel). However, a subtle difference was noted in that proliferation was not confined to the intervillus pockets in the mutant proximal intestine, as assessed both with PCNA (arrowheads in Fig 2D, middle panel) and 5‐bromo‐2‐deoxyuridine (BrdU; Fig 3E,F; see below).

Figure 3

Absence of BrdU‐labelled cells in the middle and distal intestine in _tcf4_exI/exI fish at 5 weeks post‐fertilization. (A–F) Anti‐BrdU immunohistochemistry of _tcf4_wt/wt at 2 (A), 3 (C) and 5 wpf (E) and _tcf4_exI/exI at 2 (B), 3 (C) and 5 wpf (F). BrdU‐labelled cells after 3 h pulse are observed throughout the intestinal folds at 2 and 3 wpf in mutant and wild‐type (wt) fish (black arrows in (A–D)). At 5 wpf, BrdU‐labelled cells occur between folds (black arrows in (E)). In the mutant fish, proliferation in the proximal (Prox) intestine is not restricted to the interfold pockets (black arrows in the middle panel of (F)). No BrdU‐labelled cells are observed in the middle (Mid) and distal (Dis) intestine in mutant fish (F, bottom panel). (G) BrdU cells are scored as a percentage of total cell number per analysed segment. Error bars are mean±s.d. The asterisk indicates statistically significant difference (Student's _t_‐test, _P_=0.025). At least three fish were analysed per time point per genotype. BrdU, 5‐bromo‐2‐deoxyuridine; wpf, weeks post‐fertilization.

The zebrafish intestinal epithelium is organized into epithelial folds at 2 wpf (Ng et al, 2005; Wallace et al, 2005). At this time point, mutants were indistinguishable from wild‐type siblings. We studied the onset of proliferative changes using the S‐phase marker BrdU. At 2 and 3 wpf, BrdU+ cells were found throughout the epithelium in all three intestinal segments. At 5 wpf, BrdU‐labelled cells became restricted to the ‘inter‐fold’ pockets in control fish (Fig 3E,F). First observed at 5 wpf, Tcf4 mutant fish lacked BrdU‐labelled cells in the middle and distal intestinal segment. Quantification confirmed that the percentage of BrdU+ cells was strongly reduced in the middle and distal mutant intestine, but remained unchanged in the proximal part despite differences in localization (Fig 3G).

In zebrafish, the most rostral segments of the digestive tract, the pharynx and oesophagus, develop independently from the intestinal tube and only from 58 hpf become contiguous with it (Wallace & Pack, 2003). The zebrafish is considered to be a stomach‐less fish. However, the absence of a phenotype in the most proximal mutant intestine led us to propose that zebrafish might have retained a ‘genetic footprint’ of stomach ontogeny.

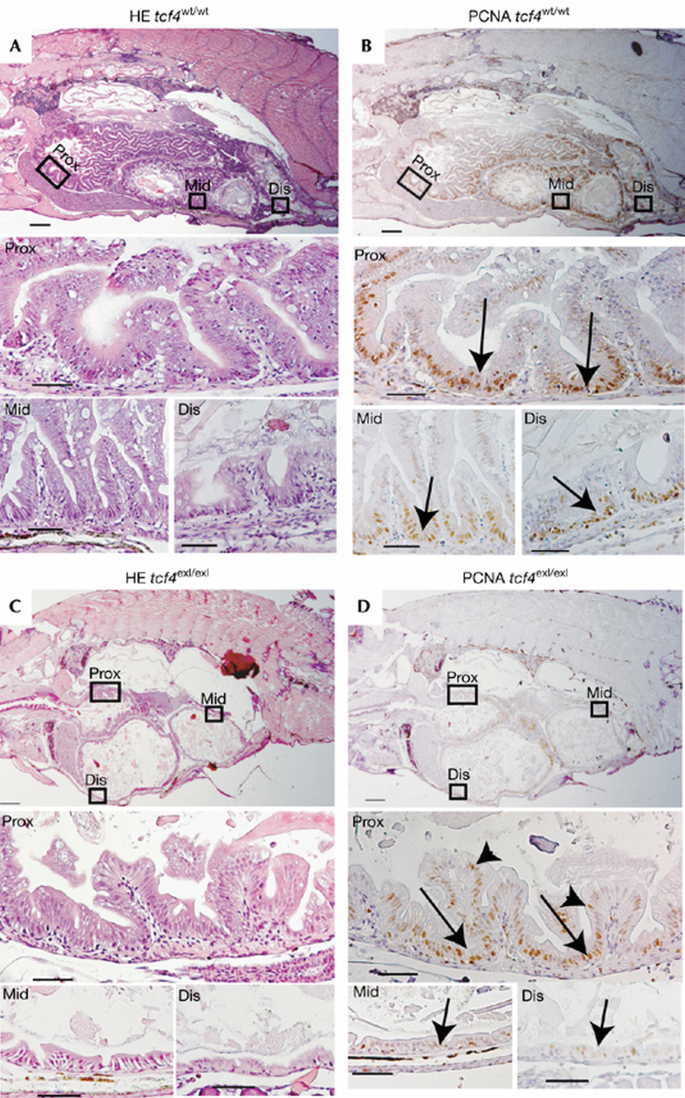

The vertebrate transcription factor Sox2 is expressed specifically in the epithelium of oesophagus and stomach. In chick, it is under the control of mesenchymal factors to induce the formation of gizzard epithelium (Ishii et al, 1998). Sox2 is also expressed in mouse and human stomach (Li et al, 2004; Tsukamoto et al, 2005). Therefore, we determined sox2 expression in the zebrafish gut epithelium. At 96 hpf, we found that the boundary of the oesophagus and the intestine coincided with the somite II/III boundary (Fig 4A). Zebrafish sox2 mRNA was found in the pharynx and oesophagus (coinciding with somite II) as described for mammals and chicken, and also in cells with intestinal morphology coinciding with somite III (arrows in Fig 4B).

Figure 4

The proximal part of zebrafish intestine is molecularly marked as stomach. (A) A wild‐type (wt) embryo at 96 hpf with oesophagus (Eso) and intestine (Int) boundaries corresponding to position of somites II and III. The inset indicates the difference in epithelial morphology between oesophagus and intestine, corresponding to somites II and III. (B) WISH for sox2 messenger RNA, expressed in the most proximal region (arrows), corresponding to somite III. (C,E) gata5 and gata6 expression starts from somite IV. (D) WISH for barx1 mRNA, depicting specific mesenchymal expression around the proximal intestinal segment, corresponding to somite III. (F) Scheme of expression domains correlated to somites at 96 hpf. hpf, hours post‐fertilization; WISH, whole‐mount in situ hybridization; L, liver; PhA, pharyngeal arches; SB, swimming bladder.

The mammalian stomach is formed by a localized swelling of the nascent gut. The mesenchyme surrounding the prospective stomach expresses the transcription factor Barx1 before morphological specialization (Tissier‐Seta et al, 1995; Kim et al, 2005). We detected barx1 expression in the presumptive anterior intestinal segment at 96 hpf in the zebrafish (Fig 4D). The domain expressing barx1 overlapped with that of sox2, but positionally coincided with somite III only (Fig 4B,D). We observed barx1 expression not only in the _lfabp_‐positive liver, but also in _lfabp_‐negative mesenchymal cells surrounding the proximal intestinal segment (supplementary Fig 1 online). The specific mesenchymal expression of barx1 is consistent with the existence of a rudimentary programme for stomach induction in the zebrafish.

Adult mouse small intestine expresses some Gata family members (Dusing & Wiginton, 2005). In zebrafish, gata5 and gata6 have been reported to be expressed in the intestine (www.zfin.org). The rostral boundary of the gata5 and gata6 expression domains in 96 hpf larvae occurred at the somite III/IV boundary (Fig 4C,E). The most proximal part of the intestinal epithelium, corresponding to the position of somite III and expressing sox2 and barx1, was devoid of the gata5 and gata6 expression domains.

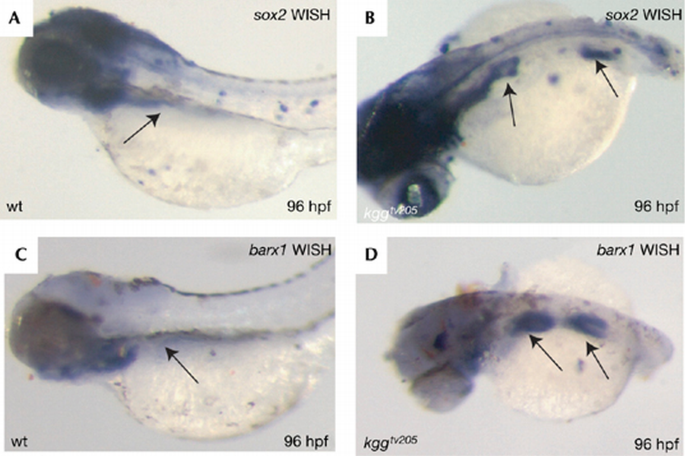

Inhibition of _caudal_‐related genes affects the formation of posterior body structures in invertebrate and vertebrate species (Macdonald & Struhl, 1986; Chawengsaksophak et al, 2004; Shinmyo et al, 2005). Loss of caudal‐type homeobox transcription factor (Cdx) genes often results in the ectopic formation of anterior structures in posterior parts of the body (Beck et al, 2003; Shimizu et al, 2006). Mutation in cdx2 induces ectopic gastric epithelium in the mouse intestine (Beck et al, 2003). Zebrafish cdx4 is evolutionarily the closest orthologue of mouse cdx2 (supplementary Fig 2 online). Accordingly, a loss of cdx4 in zebrafish kugelig (kgg) mutants leads to posterior truncation (Davidson et al, 2003). We examined whether anteroposterior patterning of the intestinal tract was affected in kgg mutants. A striking extension of the sox2 expression domain occurred towards posterior parts of the intestine (Fig 5A,B). Similarly, posterior extension of the expression domain was observed for barx1 (Fig 4C,D).

Figure 5

Loss of cdx4 induces ectopic expression of proximal intestinal markers in the middle intestine. WISH for sox2 and barx1 in wild type (wt; A,C) and kgg tv205 mutants (B,D) is shown. The arrows point to sox2 and barx1 expression. WISH, whole‐mount in situ hybridization.

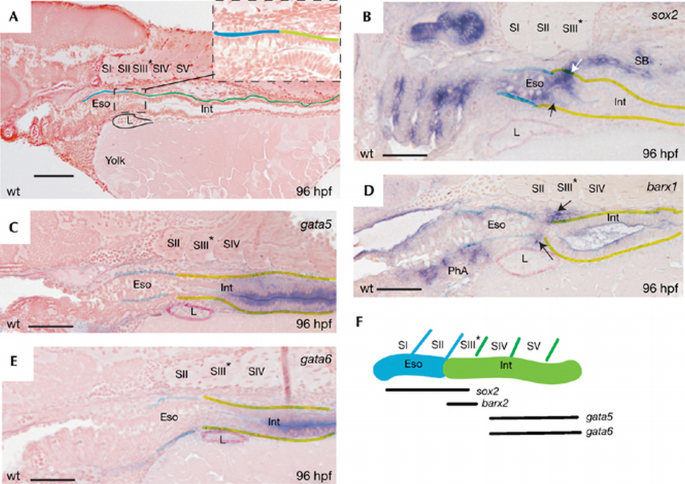

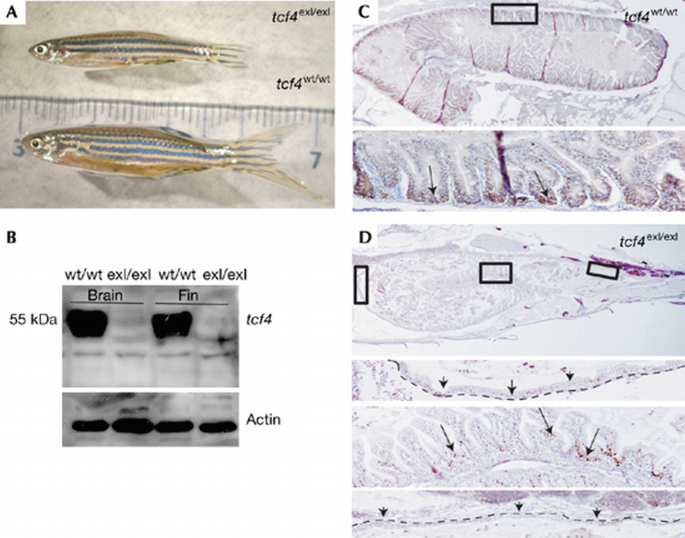

Less than 1% (3 out of 375) of Tcf4 mutant fish survived into adulthood. These fish were readily distinguishable from their siblings because of their small size, but seemed otherwise normal (Fig 6A). No correctly spliced tcf4 RNA or protein were found in these adult ‘escapers’ (Figs 1C,D, 6B). The escapers showed defects in proliferation of the intestinal epithelium. Only small, scattered patches of normal‐looking epithelium were maintained (Fig 6C,D). These adult ‘escapers’ underscored the unique function of Tcf4 in maintaining the proliferative zones of the fish intestine throughout life.

Figure 6

Gut phenotype of homozygous Tcf4 mutant ‘escaper’ fish. (A) Escaper compared with sibling is reduced in size. (B) Western blot analysis of Tcf4 protein from brain and fin tissues showing the absence of protein in escapers. (C) PCNA IHC in wild type (wt). The lower panel is a magnification of the boxed area; the arrows point to PCNA+ cells at the base of the folds. (D) PCNA IHC on Tcf4 escaper fish showing large areas of intestinal epithelium with loss of proliferation. The three lower panels are magnifications of the boxed areas. The arrows point to severely affected areas or to rare PCNA+ patches unequally distributed throughout the epithelial folds. The dashed line indicates the flat epithelial layer in this fish. IHC, immunohistochemistry; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; Tcf‐4, T‐cell factor.

In this paper, we analyse the role of the transcription factor Tcf4 in the intestine of zebrafish. Previous studies (Ng et al, 2005; Wallace et al, 2005) have reported on the early development of the gastrointestinal tract in zebrafish and have monitored gut morphogenesis until 2 wpf. Our study identifies the period between 4 and 5 wpf as a crucial transition time, when the proliferation of intestinal epithelium becomes restricted to intervillus pockets. We note a specific loss of proliferation in the middle and distal intestinal segments. This indicates that even though the intestinal epithelium in the zebrafish seems uniformly organized, differences in molecular patterning in the gastrointestinal tract must exist. We propose, on the basis of the expression of stomach markers, that the most proximal part of the intestine has a molecular code resembling that of the mammalian stomach. The absence of gastric glands in the foregut of zebrafish classifies them as stomach‐less fish. In the zebrafish databases available today, we were unable to find any orthologues of genes expressed in the definitive mammalian stomach. In a study carried out on another species of stomach‐less fish, Takifugu rubripes, an orthologue of the pepsinogen gene was identified. Its expression was restricted to the skin (Kurokawa et al, 2005), indicating that the protein had lost its function in digestion.

Our finding that the Wnt effector Tcf4 has a conserved function in the maintenance of proliferation of the intestinal epithelium agrees with the finding that neoplastic lesions in the fish intestine are caused by Wnt pathway mutations, such as those seen in human and mouse. Indeed, fish that are heterozygous for a mutation in the Wnt pathway tumour suppressor antigen‐presenting cell readily develop spontaneous and carcinogen‐induced intestinal adenomas (Haramis et al, 2006). These combined observations validate zebrafish as a model for the study of Wnt‐driven intestinal self‐renewal and tumorigenesis.

Methods

Target‐selected inactivation of the tcf4 gene and validation of the molecular nature of mutation. Fish were raised and staged as described previously (Westerfield, 1995). Amplicons of the tcf4 gene were selected for target‐selected mutagenesis and screened for mutations in a library of 4608 ENU‐mutagenized F1 fish. Fish with a mutant allele (_tcf4_hu892 or _tcf4_exI/exI) were outcrossed to wild‐type fish, and the progeny was incrossed to obtain homozygous mutants. Genotyping was carried out by using primers Tcf41F: AAAATGCCGCAGCTGAACGG and TCF43R: CGGAGAAAGCGATCCGTTCG. Mutation deletes the _Bsa_JI digestion site. RT–PCR was carried out using primers F1: CGCAGCTGAACGGCGGTG, F2: CAAAATTAGCGCTCCTCG, R1: GTGCGCGCGGTCGGAGAAAG and R2: GGCCGTCTTTCCTCCTC. For western blot analyses, a TCF4 (C19) goat polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany) was used (1:500).

Survival curve and measurement of body growth. Fish were collected once a week starting at day 7 after fertilization, then anaesthetized and body length was determined. At each time point, at least 80 fish were analysed. Subsequently, the fish were genotyped. The genotype results are presented as a graph in Fig 1D. All references to phenotype were confirmed by genotyping.

Histology, whole‐mount and double in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry. Whole‐mount in situ hybridization (WISH) and double ISH were carried out as described previously (Diks et al, 2006). The probe for sox2 was obtained from an expressed sequence tag clone with zfin accession number cb236 and for barx1, gata5 and gata6 from 7165021, 7449970 and 6963479, respectively. For immunohistochemistry (IHC), dehydrated embryos and fish were paraffin embedded and sectioned at 6 μm. Haematoxylin and eosin were used for routine histology. IHC staining with antibody for PCNA (PC10; Euro Diagnostica, Arnhem, The Netherlands) and BrdU (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was carried out as described previously (van de Wetering et al, 2002). Plastic sections from WISH were prepared as described previously (Diks et al, 2006).

BrdU labelling. Fish were incubated in 200 ml of 1 mM BrdU solution in tap water for 3 h. After the pulse, BrdU solution was replaced with tap water several times. To collect samples, fish were first anaesthetized, then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, dehydrated and paraffin embedded.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

References

- Barker N, Huls G, Korinek V, Clevers H (1999) Restricted high level expression of Tcf‐4 protein in intestinal and mammary gland epithelium. Am J Pathol 154: 29–35

Google Scholar - Beck F, Chawengsaksophak K, Luckett J, Giblett S, Tucci J, Brown J, Poulsom R, Jeffery R, Wright NA (2003) A study of regional gut endoderm potency by analysis of Cdx2 mutant chimaeric mice. Dev Biol 255: 399–406

Google Scholar - Behrens J, von Kries JP, Kuhl M, Bruhn L, Wedlich D, Grosschedl R, Birchmeier W (1996) Functional interaction of β‐catenin with the transcription factor LEF‐1. Nature 382: 638–642

Google Scholar - Chawengsaksophak K, de Graff W, Rossant J, Deschamps J, Beck F (2004) Cdx2 is essential for axial elongation in mouse development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 7641–7645

Google Scholar - Cho EA, Dressler GR (1998) TCF‐4 binds β‐catenin and is expressed in distinct regions of the embryonic brain and limbs. Mech Dev 77: 9–18

Google Scholar - Clevers H (2006) Wnt/β‐catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 127: 469–480

Google Scholar - Crosnier C, Vargesson N, Gschmeissner S, Ariza‐McNaughton L, Morrison A, Lewis J (2005) △‐Notch signaling controls commitment to a secretory fate in the zebrafish intestine. Development 132: 1093–1104

Google Scholar - Davidson AJ, Ernst P, Wang Y, Dekens MPS, Kingsley PD, Palis J, Korsmeyer SJ, Daley GQ, Zon LI (2003) cdx4 mutants fail to specify blood progenitors and can be rescued by multiple hox genes. Nature 425: 300–306

Google Scholar - Diks SH, Bink RJ, van de Water S, van Rooijen FJ, den Hertog J, Peppelenbosch M, Zivkovic D (2006) The novel gene asb11: a regulator of the size of the neural progenitor compartment. J Cell Biol 174: 581–592

Google Scholar - Dusing MR, Wiginton DA (2005) Epithelial lineages of the mall intestine have unique patterns of GATA expression. J Mol Histol 36: 15–24

Google Scholar - Gregorieff A, Grosschedl R, Clevers H (2004) Hindgut defects and transformation of the gastro‐intestinal tract in Tcf4(−/−)Tcf1(−/−) embryos. EMBO J 23: 1825–1833

Google Scholar - Haramis AP, Hurlstone A, van der Velden Y, Begthel H, van den Born M, Offerhaus GJ, Clevers H (2006) Adenomatous polyposis coli‐deficient zebrafish are susceptible to digestive tract neoplasia. EMBO Rep 7: 444–449

Google Scholar - Ishii Y, Rex M, Scotting PJ, Yasugi S (1998) Region‐specific expression of chicken Sox2 in the developing gut and lung epithelium: regulation by epithelial–mesenchymal interactions. Dev Dyn 213: 464–475

Google Scholar - Kim BM, Buchner G, Miletich I, Sharpe PT, Shivdasani RA (2005) The stomach mesenchymal transcription factor Barx1 specifies gastric epithelial identity through inhibition of transient Wnt signaling. Dev Cell 8: 611–622

Google Scholar - Korinek V, Barker N, Morin PJ, van Wichen D, de Weger R, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Clevers H (1997) Constitutive transcriptional activation by a β‐catenin–Tcf complex in APC−/− colon carcinoma. Science 275: 1784–1787

Google Scholar - Korinek V, Barker N, Willert K, Molenaar M, Roose J, Wagenaar G, Markman M, Lamers W, Destree O, Clevers H (1998a) Two members of the Tcf family implicated in Wnt/β‐catenin signaling during embryogenesis in the mouse. Mol Cell Biol 18: 1248–1256

Google Scholar - Korinek V, Barker N, Moerer P, van Donselaar E, Huls G, Peters PJ, Clevers H (1998b) Depletion of epithelial stem‐cell compartments in the small intestine of mice lacking Tcf‐4. Nat Genet 19: 379–383

Google Scholar - Kurokawa T, Uji S, Suzuki T (2005) Identification of pepsinogen gene in the genome of stomachless fish, Takifugu rubripes. Comp Biochem Physiol B 140: 133–140

Google Scholar - Li XL, Eishi Y, Bai YQ, Sakai H, Akiyama Y, Tani M, Takizawa T, Koike M, Yuasa Y (2004) Expression of the SRY‐related HMG box protein SOX2 in human gastric carcinoma. Int J Oncol 24: 257–261

Google Scholar - Macdonald PM, Struhl G (1986) A molecular gradient in early Drosophila embryos and its role in specifying the body pattern. Nature 324: 537–545

Google Scholar - Molenaar M, van de wettering M, Oosterwegel M, Petersen‐Maduro J, Godsave S, Korinek V, Roose J, Destree O, Clevers H (1996) Xtcf‐3 transcription factor mediates β‐catenin‐induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell 86: 391–399

Google Scholar - Ng AN, Jong‐Curtain TA, Mawdsley DJ, White SJ, Shin J, Appel B, Dong PD, Stainier DY, Heath JK (2005) Formation of the digestive system in zebrafish: III. Intestinal epithelium morphogenesis. Dev Biol 286: 114–135

Google Scholar - Roose J, Molenaar M, Peterson J, Hurenkamp J, Brantjes H, Moerer P, van de Wetering M, Destree O, Clevers H (1998) The Xenopus Wnt effector XTcf‐3 interacts with Groucho‐related transcriptional repressors. Nature 395: 608–612

Google Scholar - Shimizu T, Bae YK, Hibi M (2006) Cdx‐Hox code controls competence for responding to Fgfs and retinoic acid in zebrafish neural tissue. Development 133: 4709–4719

Google Scholar - Shinmyo Y, Mito T, Matsushita T, Sarashina I, Miyawaki K, Ohuchi H, Noji S (2005) Caudal is required for gnathal and thoracic patterning and for posterior elongation in intermediate‐germband cricket Gryllus bimaculatus. Mech Dev 122: 231–239

Google Scholar - Tissier‐Seta JP, Mucchielli ML, Mark M, Mattei MG, Goridis C, Brunet JF (1995) Barx1, a new mouse homeodomain transcription factor expressed in cranio‐facialectomesenchyme and the stomach. Mech Dev 51: 3–15

Google Scholar - Tsukamoto T, Mizoshita T, Mihara M, Tanaka H, Takenaka Y, Yamamura Y, Nakamura S, Ushijima T, Tatematsu M (2005) Sox2 expression in human stomach adenocarcinomas with gastric and gastric‐and‐intestinal‐mixed phenotypes. Histopathology 46: 649–658

Google Scholar - van de Wetering M et al (1997) Armadillo coactivates transcription driven by the product of the Drosophila segment polarity gene dTCF. Cell 88: 789–799

Google Scholar - van de Wetering M et al (2002) The β‐catenin/TCF‐4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell 111: 241–250

Google Scholar - Wallace KN, Pack M (2003) Unique and conserved aspects of gut development in zebrafish. Dev Biol 255: 12–29

Google Scholar - Wallace KN, Akhter S, Smith EM, Lorent K, Pack M (2005) Intestinal growth and differentiation in zebrafish. Mech Dev 122: 157–173

Google Scholar - Westerfield M (1995) The Zebrafish Book. Salem, OR: University Oregon Press

- Young RM, Reyes AE, Allende ML (2002) Expression and splice variant analysis of the zebrafish tcf4 transcription factor. Mech Dev 117: 269–273

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Zon for providing the kgg mutant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Netherlands Institute for Developmental Biology, Center for Biomedical Research, Hubrecht Institute, Uppsalalaan 8, 3584 CT, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Vanesa Muncan, Ana Faro, Anna‐Pavlina G Haramis, Adam F L Hurlstone, Erno Wienholds, Johan van Es, Jeroen Korving, Harry Begthel, Danica Zivkovic & Hans Clevers - Netherlands Cancer Institute, Plesmanlaan 121, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Anna‐Pavlina G Haramis - Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PL, UK

Adam F L Hurlstone

Authors

- Vanesa Muncan

- Ana Faro

- Anna‐Pavlina G Haramis

- Adam F L Hurlstone

- Erno Wienholds

- Johan van Es

- Jeroen Korving

- Harry Begthel

- Danica Zivkovic

- Hans Clevers

Corresponding author

Correspondence toHans Clevers.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Copyright: European Molecular Biology Organization

About this article

Cite this article

Muncan, V., Faro, A., Haramis, A.G. et al. T‐cell factor 4 (Tcf7l2) maintains proliferative compartments in zebrafish intestine.EMBO Rep 8, 966–973 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7401071

- Received: 19 December 2006

- Revised: 08 August 2007

- Accepted: 09 August 2007

- Published: 07 September 2007

- Issue date: 01 October 2007

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7401071