Differential host susceptibility and bacterial virulence factors driving Klebsiella liver abscess in an ethnically diverse population (original) (raw)

Introduction

A new, hypervirulent variant of Klebsiella pneumoniae (hvKP) has been increasingly described in the last two decades. Combinations of clinical as well as bacterial genotypic and phenotypic features distinguish this variant from the “classic” opportunistic K. pneumoniae. The first is its ability to cause life-threatening disease in healthy individuals, although diabetes mellitus is a risk factor1,2,3,4. Unique invasive syndromes include community-acquired monomicrobial pyogenic liver abscess, and a propensity for metastatic spread to unusual distant sites including the eye, brain and lung2,4,5. The second is its ability to more efficiently acquire iron, and enhanced ability to produce the polysaccharide capsule that typically results in the hypermucoviscous phenotype5,6,7,8. At least 79 capsule types of K. pneumoniae exist9. For hvKP, eight types have been described to date: K1, K2, K5, K16, K20, K54, K57 and KN11,3,10,11. The vast majority of hvKP that cause Klebsiella liver abscess (KLA) are K1 or K2 capsule types3,4,12. Through multi-locus sequence typing (MLST), sequence-type (ST) 23 was found to be strongly associated with capsule type K1, while ST25, ST86, ST375 and ST380 have been associated with capsule type K213,14,15,16.

Although the route of hvKP entry into humans has not been established, the gastrointestinal tract appears to be the dominant site of colonization. K. pneumoniae isolated from healthy carriers has identical pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profile as well as similar virulence-associated genes and median lethal dose values in mouse lethality assays as hvKP isolated from patients with liver abscess17. When mice were orally infected with hvKP, four distinct stages were observed to develop sequentially: intestinal colonization, extraintestinal dissemination, hepatic replication and septic metastasis18.

While hvKP was first discovered in the Asia Pacific Rim (e.g. Taiwan) in the mid-1980s19, it is now increasingly recognized in Western countries (e.g. North America)15,20,21. However, most cases acquired in Western countries commonly occur among Asians1,2. Inevitably, travel to the Asia Pacific Rim or exposure to people from that region is assumed to increase the risk of KLA. Indeed, hvKP strain acquisition resulting in colonization and subsequent infection from international travel has been documented22,23. Nonetheless, this risk factor is unable to account for all the KLA cases occurring outside of Asia15,20. This raises the question about the importance of host genetic susceptibility (Asians, particularly of Chinese ethnicity) versus geographically defined pathogen exposure and acquisition (Asia Pacific Rim) in driving the epidemiology of KLA. Research on hvKP is most extensive in Asia. Various associations of patient clinical features and bacterial molecular characteristics influencing KLA development have been reported from Taiwan, China, Hong Kong and Korea3,4,16,24,25. However, these clinical studies of large case series were almost exclusively conducted on ethnically homogenous populations. Therefore, the issue of genetic predisposition versus geospecific strain acquisition remains unresolved.

We leveraged on a prospective multi-center randomized clinical trial [Antibiotics for Klebsiella Liver Abscess Syndrome Study (A-KLASS)] ongoing in Singapore, where KLA is now the leading cause of liver abscess26. Singapore is a multiracial and multicultural country, consisting of 76.2% Chinese, 15% Malay, 7.4% Indian, and 1.4% other races[27](/articles/srep29316#ref-CR27 "National Population and Talent Division at the Prime Minister’s Office, Department of Statistics, Ministry of Home Affairs & Immigration and Checkpoints Authority. Population in brief. (2015) Available at: http://population.sg/population-in-brief/files/population-in-brief-2015.pdf

. (Assessed: 31st January 2016)."). Information on the prevalence of diabetes mellitus among the various ethnic groups is also available: 17.2% of Indians, 16.6% of Malays and 9.7% of Chinese have underlying diabetes[28](/articles/srep29316#ref-CR28 "Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health, Singapore. National health survey. (2011) Available at:

https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/dam/moh_web/Publications/Reports/2011/NHS2010-lowres.pdf

. (Assessed: 31st January 2016)."). In order to understand what drives the development of KLA, we collected bacterial isolates from 70 consecutive A-KLASS participants of all four ethnic groups, with information on their clinical profile and parameters. We explored the relationship between clonal distribution and virulence profiles of KLA isolates with the corresponding patient demographics and host susceptibility factors.Results

KLA patient characteristics

Seventy participants were recruited between 7 March 2013 and 19 October 2015. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 59.8 ± 11.9 years. Eighty percent (56/70) were male. Seventy-six percent (53/70) were Chinese, 21.4% (15/70) Malay, 1.4% (1/70) Indian, and 1.4% (1/70) Caucasian. Compared to Singapore’s ethnic distribution, Malays were slightly over-represented in our patient cohort with Indians under-represented, whereas Chinese and other races were appropriately represented. Type 2 diabetes mellitus was the most frequent comorbidity (47.1%, 33/70). Other common comorbidities included cardiovascular disease (41.4%, 29/70), hypertension (34.3%, 24/70) and hyperlipidemia (31.4%, 22/70). Forty percent (28/70) had multiloculated liver abscesses, and the mean abscess diameter was 57.6 ± 30.6 mm.

Table 1 KLA patient characteristics (n = 70).

Genotyping of clinical isolates

To identify the different capsule types among KLA strains isolated from these 70 patients, we genotyped the capsular polysaccharide synthesis (cps) genes via PCR-based _wzy/wzx-_typing (n = 70) and whole-genome derived _wzi-_typing (n = 27). The genotypic and phenotypic virulence profiles of all 70 isolates are summarized in Table 2. Capsule types were successfully assigned for 68 isolates. No previously defined cps loci were detected for isolates TTSH04 and NUH11, but subsequent genomic screens indicated the presence of novel cps loci in both cases, which likely correspond to novel capsule types. The cps locus in TTSH04 showed similarity to that of isolate BIDMC25 in the K. pneumoniae BIGS database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/202036). The phenotypic capsule type of BIDMC25 is unknown, and its full-length cps locus does not match any of those of the 79 published references9. Overall, capsule type K1 was the most common (64.3%, 45/70), followed by K2 (20%, 14/70), K5 (5.7%, 4/70) and K57 (2.9%, 2/70). K16, K28, K63 and the two novel cps loci were detected in one isolate each.

Table 2 Genotypic and phenotypic virulence profiles of the KLA clinical isolates (n = 70).

We further screened isolates for possession of acquired virulence genes associated with iron metabolism including kfu (ferric uptake transporter), iuc (aerobactin siderophore), iro (salmochelin siderophore) and irp (yersiniabactin siderophore). We also screened for the three known genomic copies of rmpA (regulator of mucoid phenotype A; transcriptional activator of cps genes) and expression of the hypermucoviscous phenotype. All the K1 isolates were positive for kfu, iuc and iro, whereas 93.3% (42/45) were positive for irp. All the K1 isolates were hypermucoviscous, with 97.8% (44/45) harboring two copies each of rmpA while one other isolate had a single copy. Thirteen of these K1 isolates, including one representative _irp-_negative isolate, were selected for whole-genome sequencing (WGS), which confirmed the presence of the complete sequences of the virulence-related clusters detected by PCR. Subsequent in silico MLST analysis revealed that all 13 isolates represented ST23 (Supplementary Table S1). Taken together, these findings suggest that the 45 K1 isolates are closely related, and all are likely to represent the ST23-K1 lineage.

In contrast, there was diversity of virulence gene content among the 14 K2 isolates. Thirty-six percent (5/14) were positive for kfu, 64.3% (9/14) were positive for irp, 92.9% (13/14) were positive for iuc, and 100% (14/14) were positive for iro. While 92.9% (13/14) were hypermucoviscous, there was variation in rmpA copy number: 35.7% (5/14), 57.1% (8/14) and 7.1% (1/14) harbored two, one and zero copies of rmpA, respectively. The one particular K2 isolate (named NUH04) that lacked rmpA was non-mucoviscous, consistent with rmpA regulation of the hypermucoviscous phenotype. Concordant with the PCR results, analysis of the whole genomes of five randomly selected K2 isolates showed that they each represented a distinct MLST profile (ST65, ST373, ST380, ST2038 and ST2039), highlighting the genotypic diversity of the K2 isolates (Supplementary Table S1). Of particular note, two of the K2-associated STs were newly identified in this study: ST2039 is the non-mucoviscous NUH04 strain, while ST2038 (named NUH14) is a double-locus variant of ST23. Interestingly, NUH14 was the only non-K1, non-ST23 isolate that tested PCR-positive for allS (activator of allantoin metabolism), which was carried by the other 45 K1 isolates. Therefore, NUH14 may share recent ancestry with the ST23 lineage.

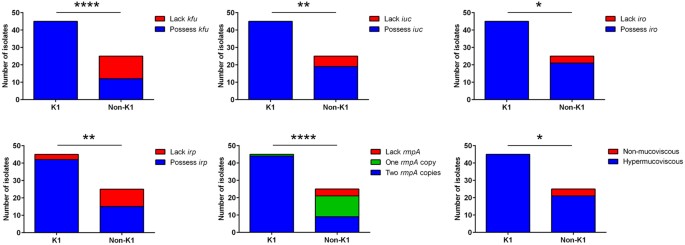

We also sequenced the whole genomes of three K5 isolates, one K16 isolate, one K28 isolate, one K57 isolate and one K63 isolate, as well as both of the novel cps isolates. Each of these nine isolates represented a distinct ST, including another newly identified one, ST2037, belonging to the novel cps isolate TTSH04 (Supplementary Table S1). Consistent with the WGS data, PCR screening revealed diversity of virulence gene content among the non-K1/K2 isolates. Fifty-five percent (6/11) were positive for iuc and irp, and 63.6% (7/11) were positive for kfu and iro. Only 72.7% (8/11) were hypermucoviscous, and there was variation in rmpA copy number: 36.4% (4/11), 36.4% (4/11) and 27.3% (3/11) harbored two, one and zero copies of rmpA, respectively. The three isolates (K28 isolate NUH29, novel cps isolates TTSH04 and NUH11) that did not possess rmpA were non-mucoviscous, again consistent with rmpA regulation of the hypermucoviscous phenotype. Taken together, the non-K1 isolates are genetically diverse whereas the K1 isolates likely represented a single clone (ST23), consistent with previous studies13,15,29. Between these two distinct groups, clonal K1 isolates carried significantly higher frequencies of virulence-associated genes (kfu, iuc, iro, irp and rmpA) compared to non-clonal, non-K1 isolates (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: K1 isolates carried higher frequencies of virulence-associated genes than non-K1 isolates.

These include kfu (100% vs 48%; P < 0.0001 by Fisher’s exact test), iuc (100% vs 76%; P = 0.001 by Fisher’s exact test), iro (100% vs 84%; P = 0.014 by Fisher’s exact test), irp (93.3% vs 60%; P = 0.001 by Fisher’s exact test) and rmpA (mean copy number: 1.98 vs 1.20; P < 0.0001 by Student’s t test). Expression of the hypermucoviscous phenotype correlated with possession of at least one rmpA copy in the genome.

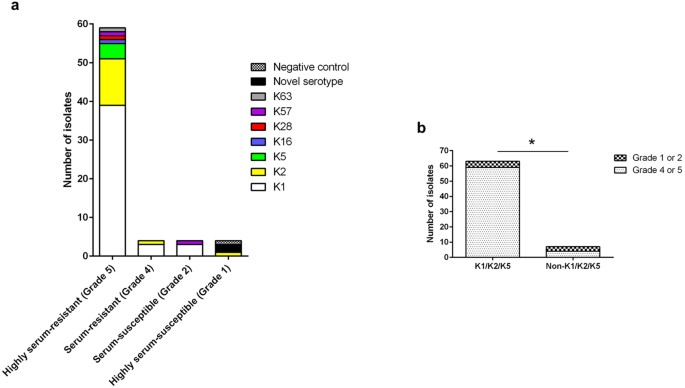

Resistance to human serum

The majority (90%, 63/70) of the isolates were resistant to pooled healthy human serum (Fig. 2a). This is generally consistent with our finding that 94.3% (66/70) of the isolates expressed the hypermucoviscous phenotype, which confers protection against the bactericidal effects of serum1,2,30. Specifically, 59/70 isolates were highly serum-resistant including one non-mucoviscous K28 strain NUH29, 4/70 isolates were serum-resistant, 4/70 isolates were serum-susceptible, and 3/70 isolates were like the non-pathogenic Escherichia coli OP50 that is highly serum-susceptible. The vast majority (93.7%, 59/63) of K1/K2/K5 isolates were classified as either highly serum-resistant or serum-resistant, compared to only 57.1% (4/7) of non-K1/K2/K5 isolates (P = 0.019; Fig. 2b). Amongst the non-K1/K2/K5 isolates, there was no association between virulence gene content and serum resistance. Therefore our data support an association between capsule types K1, K2 and K5 with the hypermucoviscous and serum-resistant phenotypes, which in turn are associated with increased virulence potential31,32.

Figure 2: K1/K2/K5 isolates were more resistant to serum exposure than non-K1/K2/K5 isolates.

(a) Serum resistance level of isolates from the different capsule types. Responses were graded as follows: grade 5 (highly serum-resistant), viable CFU after 3 hours of incubation in serum > 100% of the inoculum; grade 4 (serum-resistant), 71– 100%; grade 2 (serum-susceptible), 1–30%; grade 1 (highly serum-susceptible), 0%. The negative control, E. coli OP50, was highly-serum susceptible. (b) Comparison of prevalence of serum-resistant (grade 4 or 5) population between K1/K2/K5 isolates and non-K1/K2/K5 isolates (93.7% vs 57.1%; P = 0.019 using Fisher’s exact test).

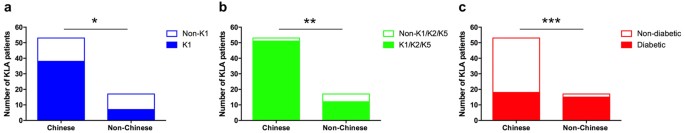

Ethnic susceptibility to capsule types

The Chinese (n = 53) in our patient cohort had a significantly higher probability of infection with K1 compared to the non-Chinese (n = 17) consisting of Malays, Indian and Caucasian (71.7% vs 41.2%; P = 0.040; Fig. 3a). Chinese were rarely infected with the uncommon KLA capsule types (i.e. non-K1/K2/K5), unlike non-Chinese who were infected with numerous non-K1/K2/K5 isolates including K16, K28, K57, K63 and novel cps isolates (3.8% vs 29.4%; P = 0.008; Fig. 3b). While only 34% of the Chinese had underlying type 2 diabetes, 88.2% of the non-Chinese were diabetic (P = 0.0001; Fig. 3c). K1 strains are known to be capable of causing KLA in healthy individuals due to its increased virulence potential (see results above), whereas non-K1 strains tend to be restricted to KLA patients with predisposing conditions such as diabetes mellitus3. Therefore, the overrepresentation of non-K1/K2/K5 K. pneumoniae KLA among non-Chinese patients can in part be explained by the higher rate of diabetes within this group.

Figure 3: The predominantly non-diabetic Chinese were more likely to be infected by K1 isolates and less likely to be infected by uncommon KLA capsule types (non-K1/K2/K5) than the predominantly diabetic non-Chinese.

(a) Comparison of prevalence of K1 infection between Chinese and non-Chinese (71.7% vs 41.2%; P = 0.040 by Fisher’s exact test). (b) Comparison of prevalence of non-K1/K2/K5 infection between Chinese and non-Chinese (3.8% vs 29.4%; P = 0.008 by Fisher’s exact test). (c) Comparison of prevalence of type 2 diabetes between Chinese and non-Chinese (34% vs 88.2%; P = 0.0001 by Fisher’s exact test).

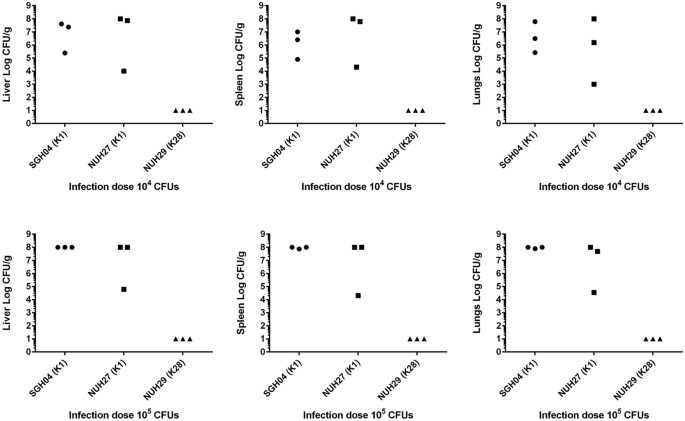

Virulence potential of K1 versus non-K1 isolates upon intraperitoneal injection into C57BL/6J mice

To verify that K1 isolates are more virulent than non-K1 isolates, we selected representative isolates for mouse infection, where variation of host susceptibility factors is significantly reduced. Two representative K1 strains of different phenotypic profiles were chosen: the highly serum-resistant strain SGH04 and the highly serum-susceptible strain NUH27. SGH04 and NUH27 are clonally related (share the same ST) and possess similar virulence gene profiles: two copies of rmpA as well as the kfu-iuc-iro-irp clusters. In contrast, the K28 strain NUH29, which represents a distinct ST, lacked rmpA and the kfu-iuc-iro-irp clusters, although it was highly serum resistant. We chose this isolate as the representative non-K1 strain. Upon intraperitoneal injection of 104 or 105 colony-forming units (CFUs) of SGH04 and NUH27, the majority of the mice became severely morbid after 24 hours post-infection. Consistent with this clinical observation, there was comparably high bacterial burden in the liver, spleen and lungs of these SGH04- and NUH27-infected mice (Fig. 4). In contrast, all the NUH29-infected mice remained healthy and appeared to have cleared the infection at the doses of 104 and 105 CFUs by 24 hours post-infection, since no bacterial load could be detected in their livers, spleens or lungs (Fig. 4). Thus, the difference in in vivo virulence between the K1 and non-K1 strains is striking, and highlights the important roles of rmpA and the kfu-iuc-iro-irp clusters in the virulence of hvKP.

Figure 4: The K1 strains SGH04 and NUH27 were more virulent than the non-K1 strain NUH29.

Bacterial burden in the organs of mice upon intraperitoneal injection with 104 or 105 CFUs of SGH04, NUH27 and NUH29. Each dot represents one infected mouse, whose liver, spleen and lungs were harvested 24 hours post-infection. Tissue homogenates that yielded no colonies were plotted with the value 10 CFU/g, which is the approximate limit of detection. The upper limit of quantification is 108 CFU/g.

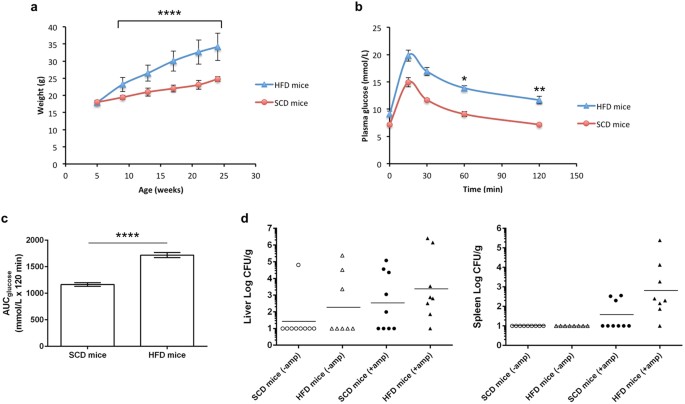

Susceptibility to extraintestinal infection upon oral inoculation of K1 into healthy control mice versus obese/type 2 diabetic mice

Our patient data had shown that K1 strains caused KLA in predominantly non-diabetic Chinese, suggesting inherent virulence in healthy individuals. We next investigated whether a K1 strain could cause similar disease in healthy mice versus a model of type 2 diabetes in mice33,34, through oral inoculation which represents a more natural route of infection. Mice on a high-fat diet (HFD) progressively gained more weight than mice on a standard chow diet (SCD) (Fig. 5a). By week 16 of diet feeding, HFD-fed mice were severely obese, with a mean weight 41.1% greater than SCD-fed mice (32.6 ± 3.5 vs 23.1 ± 1.3 g; P < 0.0001). HFD-fed mice also progressively developed glucose intolerance, as determined by oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTTs) performed at week 8, 12 and 16 (representative week-16 OGTT shown in Fig. 5b). By week 16, basal blood glucose levels were significantly higher in HFD-fed mice compared to their SCD-fed counterparts following 6 hours of fasting (9.1 ± 0.5 vs 7.2 ± 0.2 mmol/L; P = 0.002). Upon administration of a bolus of glucose following the 6-hour fast, HFD-fed mice displayed impaired ability to clear glucose in the blood compared to SCD-fed mice. Mean peak blood glucose was reached 15 minutes after glucose challenge in both HFD-fed (19.8 ± 1.0 mmol/L) and SCD-fed mice (14.9 ± 0.8 mmol/L), and was completely cleared over the remaining 105 minutes in SCD-fed mice (7.2 ± 0.2 mmol/L) but only partially eliminated in HFD-fed mice (11.7 ± 0.7 mmol/L) (P = 0.003, when comparing the percentage change at 0 and 120 minutes). This marked difference in glucose tolerance between HFD-fed and SCD-fed mice was also apparent with the area under the curve (AUC) measurement (1719.8 ± 48.2 vs 1165.1 ± 31.9 AUCglucose mmol/L × 120 minutes; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5: Incidence of extraintestinal infection was not significantly different between obese/glucose intolerant mice and healthy mice upon oral inoculation with hvKP K1.

Data in (a–c) are means ± SEM. (a) Weight of mice fed a SCD or HFD over a course of 19 weeks. Ampicillin treatment between weeks 16 to 19 did not alter body mass. (b) Plasma glucose concentrations during the OGTT following 6 hours of fasting in mice fed a SCD or HFD for 16 weeks. Percentage change from basal (fasting glucose level at 0 min) in SCD-fed mice: 15 min = + 107.6% ± 10.0, 30 min = + 64.0% ± 6.3, 60 min = 26.7% ± 5.5, 120 min = + 1.1% ± 5.3. Percentage change from basal in HFD-fed mice: 15 min = + 121.2% ± 15.8, 30 min = + 88.8% ± 12.3, 60 min = 54.9% ± 8.8, 120 min = + 28.5% ± 5.4. Glucose elimination is significantly faster in SCD-fed than HFD-fed mice (P = 0.012 and 0.003 by Student’s t test, when comparing percentage change at 0–60 minutes and 0–120 minutes, respectively). (c) Area under the curve for glucose in (b), calculated using the trapezoidal rule. (d) Bacterial burden in the extraintestinal organs of SCD-fed (healthy) and HFD-fed (obese/glucose intolerant) mice that were treated with ampicillin or not, upon oral infection with 108 CFUs of the K1 strain SGH04. Each dot represents one infected mouse, whose liver and spleen were harvested 72 hours post-infection. Horizontal bars indicate geometric means. Tissue homogenates that yielded no colonies were plotted with the value 10 CFU/g, which is the approximate limit of detection.

Following the OGTT at week 16, the HFD-fed and SCD-fed mice were further randomized into two groups. One group received sterile drinking water while the other received ampicillin water for three weeks35. We chose SGH04 as the prototype K1 strain for the oral infection at week 19 (Fig. 5d). The incidence rate of extraintestinal infection, as determined by bacterial burden in the liver and spleen 72 hours post-infection, is summarized in Table 3. In the no antibiotic treatment group, the incidence of extraintestinal infection was slightly higher in HFD-fed (37.5%, 3/8) compared to SCD-fed mice (11.1%, 1/9), but this difference is not statistically significant (P = 0.294). Expectedly, ampicillin treatment significantly increased the incidence of extraintestinal infection as opposed to no antibiotic treatment [12/17 (70.6%) vs 4/17 (23.5%); P = 0.015]. Within the ampicillin treatment group, the incidence of extraintestinal infection was also slightly higher in HFD-fed (87.5%, 7/8) compared to SCD-fed mice (55.6%, 5/9). However, this difference is not statistically significant (P = 0.294). Moreover, once extraintestinal infection was established, the average bacterial loads in the liver or spleen were comparable between HFD-fed and SCD-fed mice (P = 0.755 or P > 0.999, respectively).

Table 3 Incidence of developing extraintestinal hvKP K1 infection in healthy control mice and obese/glucose intolerant mice.

Discussion

Our study reports the association between virulence factors of hvKP and demographics and susceptibility factors of KLA patients. We found that the most virulent and widespread capsule type K1 infected the Chinese in our patient cohort at a significantly higher frequency than the non-Chinese (Malays, Indian and Caucasian). One plausible explanation for this finding could be that there is a higher intestinal carriage rate of capsule type K1 in the Chinese compared to the non-Chinese, perhaps occurring from a different environmental source of acquisition. Studies in other extraintestinal pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae such as E. coli suggest that the vehicles for strain acquisition are probably through a combination of food, water or person-to-person transmission such as close contact with family members36. Indeed, one study in Japan presented evidence of familial spread of hvKP ST23-K1, which caused KLA in two family members at different times whereas the third member was an asymptomatic carrier37. This same virulent ST23-K1 clone had been maintained among the Japanese family members for at least two years, supporting the concept that intestinal colonization is requisite for, but does not necessarily lead to clinical disease37.

In South Korea, the fecal carriage rate of K. pneumoniae in healthy individuals was found to be ~21% (248 positive stool samples out of 1,174), of which 23% were capsule type K138. In contrast, the fecal carriage rate of K. pneumoniae in healthy Chinese individuals in Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, Singapore, Malaysia, Japan, Thailand and Vietnam was found to be ~62% (592 out of 954)39. Capsule types K1/K2 accounted for ~10% in all the countries surveyed except Thailand and Vietnam, where K1-associated KLA has never been reported39. Together, these seroepidemiology studies imply that host genetic factors in combination with environmental factors modulate gut carriage of the various capsule types, to influence KLA development.

Our study also indicates that there are other factors influencing susceptibility to KLA between the various races beyond the dominant effect of K1 infection in Chinese. For example, Indians appear less prone to develop KLA than Malays or Chinese. Although the Indian community has the highest prevalence of diabetes mellitus (an established risk factor for KLA) in Singapore[28](/articles/srep29316#ref-CR28 "Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health, Singapore. National health survey. (2011) Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/dam/moh_web/Publications/Reports/2011/NHS2010-lowres.pdf

. (Assessed: 31st January 2016)."), the Indian race was still under-represented in KLA prevalence based on the population demographics. It will be informative to determine if this under-representation can be validated with a larger cohort, and whether it is due to differences in transmission and carriage rate, or due to host genetics. Therefore, it is crucial to determine the carriage of _K. pneumoniae_ and the corresponding capsule types in the intestinal tracts of the various ethnic groups, particularly in Indians, Malays and Caucasians. Data on intestinal carriage of _K. pneumoniae_ in non-Chinese is currently very scarce. In addition, unique cultural practices and the food sources regularly consumed by each ethnic group, which is likely to influence intestinal colonization, need to be thoroughly examined to identify the environmental reservoir of the different typeable strains.The Chinese in our patient cohort were mostly non-diabetic, whereas the vast majority of non-Chinese had underlying type 2 diabetes. Consistent with this, Fang et al. had previously reported that K1 strains are capable of causing KLA in healthy individuals with no significant medical histories, whereas non-K1 (particularly, non-K1/K2) strains tend to cause disease in patients with predisposing conditions such as diabetes mellitus3. Our mouse infection experiments showed that representative K1 isolates were more virulent than a representative non-K1 isolate, similar to the findings of previous studies40. Furthermore, our genotypic data revealed that K1 isolates were more commonly associated with acquired virulence genes than non-K1 isolates, supporting the hypothesis that the former have an increased virulence potential, which presumably facilitates disease development among otherwise healthy individuals.

Lin et al. had reported that streptozocin-induced type 1 diabetic mice were more prone to develop extraintestinal infection than naive mice upon oral infection with the K2 strain CG4341. Our diet-induced obesity-dependent mouse model mimics type 2 diabetes and is more representative of the clinical profile of most KLA patients. In our model, the incidence rate of extraintestinal infection caused by a representative K1 strain was not significantly higher in obese/glucose intolerant mice than in control mice. This result supports the notion that K1 isolates can cause KLA independent of underlying diseases in the host3, and is also consistent with our clinical finding that most of the K1 KLA cases occurred in Chinese patients who did not have type 2 diabetes.

In conclusion, we show that KLA infections in multi-ethnic Singapore fall into two groups: 1) genetically homogenous, hypervirulent K1 capsule type in non-diabetic Chinese, and 2) genetically heterogeneous non-K1 capsule types in diabetic non-Chinese. Our work paves the way for future investigation into the unique transmission patterns and/or genetic predisposition of the various races in driving the epidemiology of KLA.

Methods

Recruitment of participants and collection of demographics and clinical information

Study participants were prospectively recruited as part of the A-KLASS clinical trial across three academic medical centers in Singapore26. Inclusion criteria include: inpatients, age ≥ 21 years, abdominal imaging suggestive of liver abscess and positive blood or abscess fluid culture for K. pneumoniae. Exclusion criteria include: polymicrobial liver abscess, endophthalmitis, central nervous system abscess or severe sepsis at the screening. Information collected at screening include: age, sex, ethnicity, presence of comorbidities, and results of abdominal imaging.

PCR analysis

K. pneumoniae capsule type was determined by allele-specific PCR amplification of the cps gene cluster at the wzy and wzx loci3; for non-discriminatory strains of _wzy/wzx-_typing, wzi sequencing was performed42. Additionally, genotyping for the presence of key virulence-associated genes including kfu, iuc, iro, irp, rmpA and allS was performed3,10,12. E. coli DH5α was selected as a negative control. Specific primers used to detect the alleles of the target gene sequences are tabulated in Supplementary Table S2.

WGS and analysis

Twenty-seven K. pneumoniae isolates were subjected to whole-genome shotgun sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. DNA was extracted using GenElute™ bacterial genomic DNA kit protocol (Sigma-Aldrich). Libraries were constructed using Nextera XT kits and 150-bp sequence reads were generated. Reads were filtered to remove sequences with a mean Phred quality score < 30. Genomes were assembled de novo using Spades version 3.6.043. In silico MLST, wzi allele typing and virulence gene screening was performed using SRST244 and K. pneumoniae BIGS database (http://bigsdb.web.pasteur.fr/klebsiella/)29. Novel MLST and wzi allele sequences were submitted to the K. pneumoniae BIGS database for assignment of allele numbers following extraction from de novo assembled contigs. The wzi allele assignments were checked for associations with known capsule types and compared with PCR typing results. Where neither PCR typing nor wzi alleles could be matched to a known capsule type (n = 2), BLASTn searches were used to locate the conserved galF and ugd flanking genes to extract the putative capsule loci (i.e. sequence between the flanking genes) from the assemblies as described previously45. BLASTn searches were used to compare the relevant assembled contigs to the 79 known complete Klebsiella capsular locus sequences9, NCBI Genbank database and K. pneumoniae BIGS database.

String test for hypermucoviscosity

String test to determine bacterial hypermucoviscosity was performed as described previously5. Briefly, a bacteriologic loop was used to stretch a mucoviscous string from a second subculture of K. pneumoniae colony on blood agar (Sigma-Aldrich). Hypermucoviscosity is semi-quantitatively defined by the formation of viscous strings > 5 mm in length.

Serum resistance assays

Bacterial susceptibility to healthy pooled human serum was determined by the method of Podschun et al.46, with slight modifications. Briefly, bacterial strains were diluted to 1 × 106 CFU/mL in PBS. Next, 25 uL of bacterial suspension was added to 75 uL of pooled healthy human serum (Sigma-Aldrich). Viability was determined immediately and after 3 hours of incubation at 37 °C by plating out serial dilutions on LB agar. Responses were graded as follows: grade 5 (highly serum-resistant), viable CFU after 3 hours of incubation in serum > 100% of the inoculum; grade 4 (serum-resistant), 71–100%; grade 2 (serum-susceptible), 1–30%; grade 1 (highly serum-susceptible), 0%. All assays were repeated at least three times.

Mouse model for intraperitoneal injection with K. pneumoniae

Eight-week-old C57BL/6J mice (n = 18) were infected with the K1 strains SGH04 and NUH27 or the K28 strain NUH29 via intraperitoneal injection at doses of 104 and 105 CFUs in 100 μL PBS. Mice were euthanized 24 hours post-infection, and liver, spleen and lungs were harvested to determine bacterial burden by plating serial dilutions on HiCrome™ Klebsiella selective agar (Sigma-Aldrich).

Type 2 diabetes mouse model for oral infection with K. pneumoniae

Five-week-old C57BL/6 J mice (n = 34) were fed ad libitum with either SCD or HFD containing 35% lard (Harlan Teklad, Cat# TD.03584) under specific pathogen-free conditions. Following 8, 12 and 16 weeks of diet feeding, OGTTs were performed. After the final OGTT at week 16, the SCD-fed and HFD-fed mice were each randomized into two groups: the first group received normal untreated drinking water while the second group were administered with clinical-grade ampicillin (Sandoz, 1 g/L) in the drinking water for three weeks. Upon cessation of antibiotic treatment, mice were allowed to recover for 24 hours (i.e. ampicillin water replaced with normal drinking water). All 24-week-old mice were then orally infected with 108 CFUs of the K1 strain SGH04 in 100 μL PBS using a 20-gauge, 38 mm length, flexible plastic feeding tube with soft elastomer tip (Prime Bioscience). Mice were euthanized 72 hours post-infection, and liver and spleen were harvested to determine bacterial burden by plating serial dilutions on HiCrome™ Klebsiella selective agar (Sigma-Aldrich).

OGTTs

OGTTs were performed according to the recommendations by Andrikopoulos et al.47. Briefly, mice were fasted for six hours prior to administration with 2 g/kg glucose into the stomach via oral gavage using a 20-gauge, 38 mm length, flexible plastic feeding tube with soft elastomer tip (Prime Bioscience). Blood was drawn at 0, 15, 30, 60 and 120 minutes post glucose challenge by puncturing the lateral tail vein, and blood glucose was measured using Accu-Chek® Performa glucose meter and test strips (Roche).

Ethics statement

The A-KLASS protocol and the associated informed consent documents were reviewed and approved by National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board, SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board and Health Science Authority. Study procedures were conducted in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations, and written informed consent was obtained from all human participants. The animal protocols were reviewed, approved and carried out in strict accordance to the recommendations by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee from the National University of Singapore.

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism 6, with the use of Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous data, Student’s t test for normally distributed continuous data and Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed continuous data. P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lee, I. R. et al. Differential host susceptibility and bacterial virulence factors driving Klebsiella liver abscess in an ethnically diverse population. Sci. Rep. 6, 29316; doi: 10.1038/srep29316 (2016).

References

- Shon, A. S., Bajwa, R. P. & Russo, T. A. Hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae: a new and dangerous breed. Virulence 4, 107–118, doi: 10.4161/viru.22718 (2013).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Siu, L. K., Yeh, K. M., Lin, J. C., Fung, C. P. & Chang, F. Y. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 12, 881–887, doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70205-0 (2012).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Fang, C. T. et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae genotype K1: an emerging pathogen that causes septic ocular or central nervous system complications from pyogenic liver abscess. Clinical Infectious Diseases 45, 284–293, doi: 10.1086/519262 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Fung, C. P. et al. A global emerging disease of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: is serotype K1 an important factor for complicated endophthalmitis? Gut 50, 420–424 (2002).

Article Google Scholar - Fang, C. T., Chuang, Y. P., Shun, C. T., Chang, S. C. & Wang, J. T. A novel virulence gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains causing primary liver abscess and septic metastatic complications. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 199, 697–705, doi: 10.1084/jem.20030857 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Holt, K. E. et al. Genomic analysis of diversity, population structure, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae, an urgent threat to public health. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 112, E3574–E3581, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501049112 (2015).

Article CAS ADS Google Scholar - Russo, T. A. et al. Hypervirulent K. pneumoniae secretes more and more active iron-acquisition molecules than “classical” K. pneumoniae thereby enhancing its virulence. PLoS One 6, e26734, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026734 (2011).

Article CAS ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hsu, C. R., Lin, T. L., Chen, Y. C., Chou, H. C. & Wang, J. T. The role of Klebsiella pneumoniae rmpA in capsular polysaccharide synthesis and virulence revisited. Microbiology 157, 3446–3457, doi: 10.1099/mic.0.050336-0 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Pan, Y. J. et al. Genetic analysis of capsular polysaccharide synthesis gene clusters in 79 capsular types of Klebsiella spp. Scientific Reports 5, 15573, doi: 10.1038/srep15573 (2015).

Article CAS ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cheng, N. C. et al. Recent trend of necrotizing fasciitis in Taiwan: focus on monomicrobial Klebsiella pneumoniae necrotizing fasciitis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 55, 930–939, doi: 10.1093/cid/cis565 (2012).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Pan, Y. J. et al. Capsular polysaccharide synthesis regions in Klebsiella pneumoniae serotype K57 and a new capsular serotype. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 46, 2231–2240, doi: 10.1128/JCM.01716-07 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yu, W. L. et al. Comparison of prevalence of virulence factors for Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscesses between isolates with capsular K1/K2 and non-K1/K2 serotypes. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 62, 1–6, doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.04.007 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Struve, C. et al. Mapping the Evolution of Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. mBio 6, e00630, doi: 10.1128/mBio.00630-15 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bialek-Davenet, S., Nicolas-Chanoine, M. H., Decre, D. & Brisse, S. Microbiological and clinical characteristics of bacteraemia caused by the hypermucoviscosity phenotype of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Korea. Epidemiology and Infection 141, 188, doi: 10.1017/S0950268812002051 (2013).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Decre, D. et al. Emerging severe and fatal infections due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in two university hospitals in France. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 49, 3012–3014, doi: 10.1128/JCM.00676-11 (2011).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chung, D. R. et al. Evidence for clonal dissemination of the serotype K1 Klebsiella pneumoniae strain causing invasive liver abscesses in Korea. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 46, 4061–4063, doi: 10.1128/JCM.01577-08 (2008).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Fung, C. P. et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae in gastrointestinal tract and pyogenic liver abscess. Emerging Infectious Diseases 18, 1322–1325, doi: 10.3201/eid1808.111053 (2012).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Tu, Y. C. et al. Genetic requirements for Klebsiella pneumoniae-induced liver abscess in an oral infection model. Infection and Immunity 77, 2657–2671, doi: 10.1128/IAI.01523-08 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang, J. H. et al. Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clinical Infectious Diseases 26, 1434–1438 (1998).

Article CAS Google Scholar - McCabe, R., Lambert, L. & Frazee, B. Invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae infections, California, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases 16, 1490–1491, doi: 10.3201/eid1609.100386 (2010).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Nadasy, K. A., Domiati-Saad, R. & Tribble, M. A. Invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae syndrome in North America. Clinical Infectious Diseases 45, e25–28, doi: 10.1086/519424 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Pomakova, D. K. et al. Clinical and phenotypic differences between classic and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumonia: an emerging and under-recognized pathogenic variant. European Journal Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 31, 981–989, doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1396-6 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Gunnarsson, G. L., Brandt, P. B., Gad, D., Struve, C. & Justesen, U. S. Monomicrobial necrotizing fasciitis in a white male caused by hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae. Journal of Medical Microbiology 58, 1519–1521, doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.011064-0 (2009).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Lin, J. C. et al. Genotypes and virulence in serotype K2 Klebsiella pneumoniae from liver abscess and non-infectious carriers in Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan. Gut Pathogens 6, 21, doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-6-21 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Li, W. et al. Increasing occurrence of antimicrobial-resistant hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in China. Clinical Infectious Diseases 58, 225–232, doi: 10.1093/cid/cit675 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Molton, J. et al. Oral versus intravenous antibiotics for patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 14, 364, doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-364 (2013).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - National Population and Talent Division at the Prime Minister’s Office, Department of Statistics, Ministry of Home Affairs & Immigration and Checkpoints Authority. Population in brief. (2015) Available at: http://population.sg/population-in-brief/files/population-in-brief-2015.pdf. (Assessed: 31st January 2016).

- Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health, Singapore. National health survey. (2011) Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/dam/moh_web/Publications/Reports/2011/NHS2010-lowres.pdf. (Assessed: 31st January 2016).

- Bialek-Davenet, S. et al. Genomic definition of hypervirulent and multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal groups. Emerging Infectious Diseases 20, 1812–1820, doi: 10.3201/eid2011.140206 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cheng, H. Y. et al. RmpA regulation of capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis in Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. Journal of Bacteriology 192, 3144–3158, doi: 10.1128/JB.00031-10 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Brisse, S. et al. Virulent clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae: identification and evolutionary scenario based on genomic and phenotypic characterization. PLoS One 4, e4982, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004982 (2009).

Article CAS ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Simoons-Smit, A. M., Verwey-van Vught, A. M., Kanis, I. Y. & MacLaren, D. M. Virulence of Klebsiella strains in experimentally induced skin lesions in the mouse. Journal of Medical Microbiology 17, 67–77, doi: 10.1099/00222615-17-1-67 (1984).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Winzell, M. S. & Ahren, B. The high-fat diet-fed mouse: a model for studying mechanisms and treatment of impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 53 Suppl 3, S215–219 (2004).

Article Google Scholar - Surwit, R. S., Kuhn, C. M., Cochrane, C., McCubbin, J. A. & Feinglos, M. N. Diet-induced type II diabetes in C57BL/6J mice. Diabetes 37, 1163–1167 (1988).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lin, Y. T., Liu, C. J., Yeh, Y. C., Chen, T. J. & Fung, C. P. Ampicillin and amoxicillin use and the risk of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess in Taiwan. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 208, 211–217, doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit157 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Johnson, J. R. & Russo, T. A. Molecular epidemiology of extraintestinal pathogenic (uropathogenic) Escherichia coli. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 295, 383–404, doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.07.005 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Harada, S. et al. Familial spread of a virulent clone of Klebsiella pneumoniae causing primary liver abscess. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 49, 2354–2356, doi: 10.1128/JCM.00034-11 (2011).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chung, D. R. et al. Fecal carriage of serotype K1 Klebsiella pneumoniae ST23 strains closely related to liver abscess isolates in Koreans living in Korea. European Journal Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 31, 481–486, doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1334-7 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lin, Y. T. et al. Seroepidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae colonizing the intestinal tract of healthy Chinese and overseas Chinese adults in Asian countries. BMC Microbiology 12, 13, doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-13 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Fung, C. P. et al. Immune response and pathophysiological features of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscesses in an animal model. Laboratory Investigation 91, 1029–1039, doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.52 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lin, Y. C. et al. Activation of IFN-gamma/STAT/IRF-1 in hepatic responses to Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. PLoS One 8, e79961, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079961 (2013).

Article CAS ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Brisse, S. et al. wzi Gene sequencing, a rapid method for determination of capsular type for Klebsiella strains. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 51, 4073–4078, doi: 10.1128/JCM.01924-13 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bankevich, A. et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology 19, 455–477, doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 (2012).

Article CAS MathSciNet PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Inouye, M. et al. SRST2: Rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Medicine 6, 90, doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0090-6 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wyres, K. L. et al. Extensive Capsule Locus Variation and Large-Scale Genomic Recombination within the Klebsiella pneumoniae Clonal Group 258. Genome Biology and Evolution 7, 1267–1279, doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv062 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Podschun, R., Sievers, D., Fischer, A. & Ullmann, U. Serotypes, hemagglutinins, siderophore synthesis, and serum resistance of Klebsiella isolates causing human urinary tract infections. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 168, 1415–1421 (1993).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Andrikopoulos, S., Blair, A. R., Deluca, N., Fam, B. C. & Proietto, J. Evaluating the glucose tolerance test in mice. AJP Endocrinology and Metabolism 295, E1323–1332, doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90617.2008 (2008).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank the A-KLASS study team including all research assistants, as well as staff of the Singapore Clinical Research Network and Singapore Infectious Diseases Initiative for their support of this work. We also thank Tse Hsien Koh for critical comments and reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to the team of curators of the Institut Pasteur MLST and whole-genome MLST databases for curating the data and making them publicly available at http://bigsdb.web.pasteur.fr/. The A-KLASS clinical trial was funded by National Medical Research Council of Singapore (NMRC/CNIG/1101/2013) and Singapore Infectious Diseases Initiative (SIDI/2013/006). The genome analysis was funded by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (grants #1043822 and #1061409 to K.E.H.) and Victorian Life Sciences Computation Initiative (grant #VR0082). All other aspects of the work were supported by National University of Singapore, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine Aspiration Fund (NUHSRO/2014/068/AF-New Idea/03 to Y.H.G.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Biochemistry, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore,

I. Russel Lee, Jocelyn Wong, Chu Han Hoh & Yunn-Hwen Gan - Division of Infectious Diseases, University Medicine Cluster, National University Health System, Singapore

James S. Molton & Sophia Archuleta - Department of Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore,

James S. Molton, David C. Lye & Sophia Archuleta - Centre for Systems Genomics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, 3010, Victoria, Australia

Kelly L. Wyres, Claire Gorrie & Kathryn E. Holt - Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Bio21 Molecular Science and Biotechnology Institute, University of Melbourne, Parkville, 3010, Victoria, Australia

Kelly L. Wyres, Claire Gorrie & Kathryn E. Holt - Department of Laboratory Medicine, Microbiology Unit, National University Hospital, Singapore

Jeanette Teo - Department of Infectious Diseases, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

Shirin Kalimuddin - Communicable Disease Center, Institute of Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore

David C. Lye

Authors

- I. Russel Lee

- James S. Molton

- Kelly L. Wyres

- Claire Gorrie

- Jocelyn Wong

- Chu Han Hoh

- Jeanette Teo

- Shirin Kalimuddin

- David C. Lye

- Sophia Archuleta

- Kathryn E. Holt

- Yunn-Hwen Gan

Contributions

I.R.L. and Y.H.G. designed the project. J.S.M., S.K., D.C.L. and S.A. recruited the patients and analyzed the clinical data. J.T. purified the clinical isolates. I.R.L. performed the bacterial DNA extractions, PCR experiments, serum resistance assays and statistical analysis. K.L.W., C.G. and K.E.H. performed the WGS/MLST analysis. I.R.L. and J.W. performed the OGTTs. I.R.L., J.W. and C.H.H. performed the mouse infection experiments. I.R.L. and Y.H.G. wrote the paper. J.S.M., K.L.W., D.C.L., S.A. and K.E.H. reviewed the paper and provided recommendations. Y.H.G. coordinated and oversaw the project.

Corresponding author

Correspondence toYunn-Hwen Gan.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, I., Molton, J., Wyres, K. et al. Differential host susceptibility and bacterial virulence factors driving Klebsiella liver abscess in an ethnically diverse population.Sci Rep 6, 29316 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29316

- Received: 05 February 2016

- Accepted: 15 June 2016

- Published: 13 July 2016

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29316