A link between MAP kinase and p34cdc2/cyclin B during oocyte maturation: p90rsk phosphorylates and inactivates the p34cdc2 inhibitory kinase Myt1 (original) (raw)

Introduction

Xenopus laevis oocytes are naturally arrested in late G2 of the first meiotic division and are induced to enter into M‐phase of meiosis upon exposure to progesterone. The events of meiotic maturation, including germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD), chromosome condensation and formation of the metaphase spindles are associated with the activation of maturation‐promoting factor (MPF), a regulatory factor involved in mitosis initiation in eukaryotic cells (Masui and Markert, 1971; Masui and Clarke, 1979). MPF is composed of a regulatory subunit, cyclin B, and a catalytic subunit, the protein kinase p34cdc2, whose phosphorylation state is very important for the activity of the p34cdc2/cyclin B complex. In particular, p34cdc2 phosphorylation on either Thr14 or Tyr15 mediated by Wee1 family kinases results in MPF inactivation (reviewed by Coleman and Dunphy, 1994; Morgan, 1995; Lew and Kornbluth, 1996).

Translation of mRNA for the protein kinase Mos is required for the progesterone‐induced maturation of Xenopus oocytes (Sagata et al., 1988, 1989; Kanki and Donoghue, 1991; Sheets et al., 1995). Mos is an efficient activator of MAPK kinase (Nebreda and Hunt, 1993; Nebreda et al., 1993b; Posada et al., 1993; Shibuya and Ruderman, 1993), and injection of neutralizing antibodies against MAPK kinase inhibits Mos‐induced oocyte maturation (Kosako et al., 1994). This suggests that Mos activates p34cdc2/cyclin B through the MAPK cascade. Consistent with this hypothesis, injection of either constitutively active MAPK kinase or thiophosphorylated MAPK can trigger the maturation of Xenopus oocytes independently of any progesterone stimulation (Gotoh et al., 1995; Haccard et al., 1995; Huang et al., 1995). It should be noted, however, that although the Mos–MAPK pathway is likely to have an important role in oocyte maturation, there is also evidence that translation of mRNA(s) other than Mos is required to activate MPF during progesterone‐induced maturation (Nebreda et al., 1995; Barkoff et al., 1998).

Little is known of how MAPK triggers MPF activation and the maturation of oocytes. A well characterized substrate for MAPK is the 90 kDa ribosomal S6 kinase (p90rsk or S6KII), a serine/threonine protein kinase originally identified in Xenopus oocytes as a kinase that phosphorylates the S6 protein of the ribosomal 40S subunit in vitro (Erikson and Maller, 1986). Xenopus p90rsk is most similar to the mammalian Rsk1/Rsk2 protein kinases (also referred to as MAPKAP kinase‐1a and ‐1b) (Alcorta et al., 1989), which can be phosphorylated and activated in vitro and in vivo by p42Erk2 and p44Erk1 MAPKs (Sturgill et al., 1988; Chung et al., 1991; Alessi et al., 1995; Zhao et al., 1996). In G2‐arrested Xenopus oocytes, inactive p90rsk is associated with inactive MAPK in a heterodimer which dissociates upon phosphorylation and activation of the two kinases (Hsiao et al., 1994), suggesting that p90rsk has a role in oocyte maturation.

In Xenopus oocytes, there is a pre‐formed stock of inactive p34cdc2/cyclin B complexes (pre‐MPF) in which p34cdc2 is phosphorylated on Thr14 and Tyr15 as well as Thr161 (Cyert and Kirschner, 1988; Gautier and Maller, 1991; Kobayashi et al., 1991). Thus, the activation of pre‐MPF during oocyte maturation requires the dephosphorylation of p34cdc2 on Thr14 and Tyr15, probably catalysed by the dual‐specificity phosphatase Cdc25C (Dunphy and Kumagai, 1991; Gautier et al., 1991; Kumagai and Dunphy, 1991; Strausfeld et al., 1991). In addition to an increased activity of Cdc25C, inhibition of the kinases that phosphorylate p34cdc2 on Thr14 and Tyr15 may also trigger the activation of p34cdc2/cyclin B complexes (Atherton‐Fessler et al., 1994). The prototype of the p34cdc2 inhibitory kinases is Wee1, the negative regulator of mitosis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. However, the first cloned human and Xenopus Wee1 homologues phosphorylate p34cdc2 only on Tyr15 but not Thr14, supporting the existence of a separate Thr14 kinase (Parker and Piwnica‐Worms, 1992; McGowan and Russell, 1993; Mueller et al., 1995a). A kinase activity that can phosphorylate p34cdc2 on Thr14 was later detected in Xenopus extracts; this enzyme is associated with membranes and can be separated from a Tyr15‐specific kinase activity in the soluble fraction (Atherton‐Fessler et al., 1994; Kornbluth et al., 1994). A candidate cDNA for this activity, named Myt1, has been cloned from Xenopus (Mueller et al., 1995b) and humans (Booher et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1997). Myt1 encodes a membrane‐associated Wee1 homologue that can phosphorylate p34cdc2 on both Thr14 and Tyr15. As expected, and in contrast to Cdc25C whose activity increases during mitosis, the activity of both Wee1 and Myt1 declines during mitosis, therefore contributing to the fall in the inhibitory phosphorylation of p34cdc2 at this stage of the cell cycle. Cdc25C, Wee1 and Myt1 all become heavily phosphorylated during mitosis (M phase) and these phosphorylations correlate with the increased activity of Cdc25C (Izumi et al., 1992; Kumagai and Dunphy, 1992, 1996; Izumi and Maller, 1993; Hoffmann et al., 1993) and the inhibition of Wee1 and Myt1 (Tang et al., 1993; McGowan and Russell, 1995; Mueller et al., 1995a,b; Booher et al., 1997).

A possible connection between MAPK and the activation of pre‐MPF in oocytes comes from the recent observation that MAPK down‐regulates an activity which in turn inactivates p34cdc2/cyclin B in G2‐arrested oocytes (Abrieu et al., 1997). This inhibitory activity targeted by MAPK could correspond to Thr14–Tyr15 p34cdc2 kinases such as Wee1 and Myt1. Since Wee1 is not present in G2‐arrested oocytes and is synthesized only upon progesterone stimulation (Murakami and Vande Woude, 1998), it is not likely to keep pre‐MPF in an inactive state. Thus, Myt1 may be the MPF inhibitory activity down‐regulated by MAPK in Xenopus oocytes.

Here we report that Myt1 is a target of MAPK‐activated p90rsk. Thus, p90rsk phosphorylates the C‐terminal regulatory domain of Myt1 and down‐regulates the inhibitory activity of Myt1 on p34cdc2/cyclin B1 complexes in vitro. We also show that Myt1 becomes phosphorylated during oocyte maturation and that p90rsk and Myt1 are associated in mature oocytes. Our results indicate that p90rsk–Myt1 provides a link between the activation of MAPK and MPF during Xenopus oocyte maturation.

Results

Identification of protein kinases in Xenopus cell‐free extracts that phosphorylate Myt1 in vitro

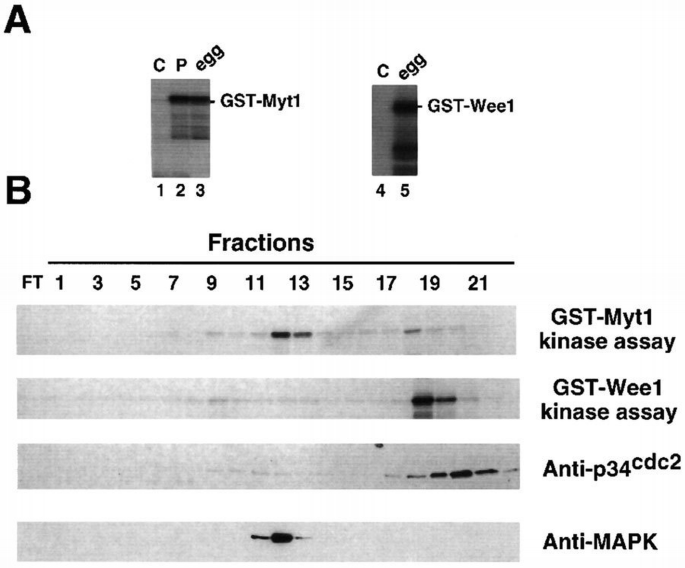

In addition to the catalytic domain, Myt1 contains a region which includes many potential phosphorylation sites and is therefore likely to have a regulatory role. To identify protein kinases that can phosphorylate and potentially regulate Xenopus Myt1, we fused the non‐catalytic regions of Myt1 (C‐terminal half) to glutathione _S_‐transferase (GST) and used the bacterially produced fusion protein as a substrate in kinase assays with Xenopus cell‐free extracts. As shown in Figure 1A, GST–Myt1 can be phosphorylated efficiently in vitro by cell‐free extracts prepared from either eggs (lane 3) or progesterone‐matured oocytes (lane 2), but not from control, G2‐arrested oocytes (lane 1). We then used GST–Myt1 to screen Xenopus egg extracts fractionated by Mono Q chromatography and we detected two peaks of kinase activity that phosphorylate GST–Myt1 in vitro (Figure 1B, GST–Myt1). As a control we also fused GST to the non‐catalytic region of Wee1 (N‐terminal half) and found that GST–Wee1 can also be phosphorylated in vitro by cell‐free extracts prepared from unfertilized eggs (Figure 1A, lane 5) but not from control, G2‐arrested oocytes (Figure 1A, lane 4). When GST–Wee1 was used as a substrate to analyse the Mono Q‐fractionated egg extracts, we found that most of the activity phosphorylating GST–Wee1 eluted in different fractions from those containing the major peak of activity that phosphorylates GST–Myt1 (Figure 1B). The same Mono Q fractions were also analysed by immunoblot with anti‐p34cdc2 and anti‐MAPK antibodies to identify the positions where these two protein kinases elute. We found that the major peak of kinase activity phosphorylating GST–Myt1 overlaps with the fractions where the p42Mpk1 MAPK is detected (Figure 1B, anti‐MAPK), whereas the major kinase activity phosphorylating GST–Wee1 overlaps with some of the fractions where p34cdc2 eluted (Figure 1B, anti‐p34cdc2).

Figure 1

Identification of protein kinase activities in Xenopus cell‐free extracts that phosphorylate GST–Myt1 and GST–Wee1 in vitro. (A) Cell‐free extracts prepared from either eggs (in vivo mature oocytes, lanes 3 and 5), oocytes matured in vitro by progesterone (lane 2) or control, G2‐arrested oocytes (lanes 1 and 4) were used to phosphorylate GST–Myt1 (lanes 1–3) or GST–Wee1 (lanes 4 and 5). (B) Egg extracts were ultracentrifuged and then fractionated by Mono Q chromatography. The fractions were either used in kinase assays with GST–Myt1 or GST–Wee1 as the substrate, or analysed by immunoblotting using anti‐p34cdc2 or anti‐Mpk1 MAPK antibodies, as indicated.

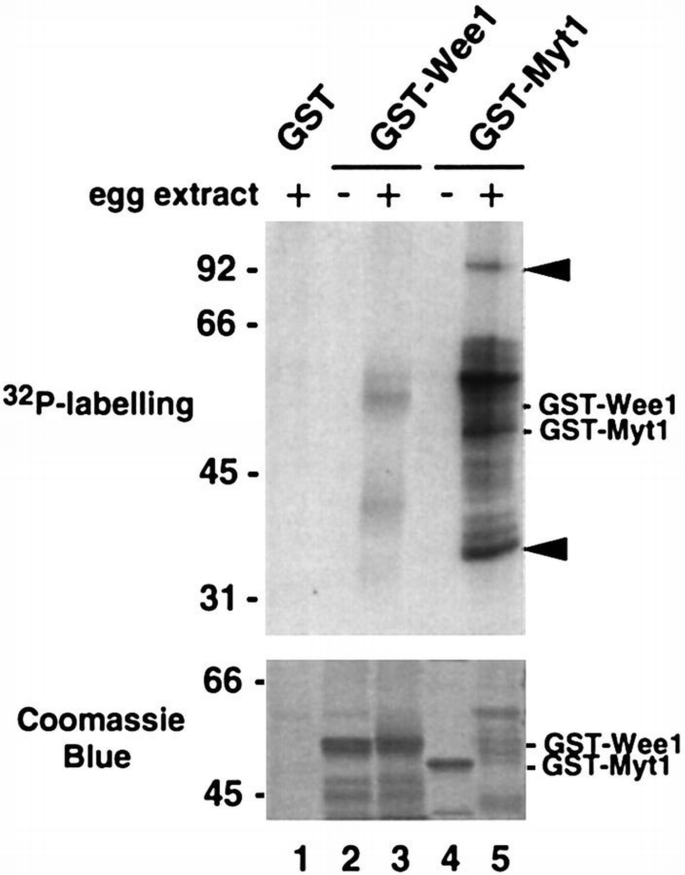

To gain further information on the protein kinase(s) that phosphorylates GST–Myt1, we used the fusion protein for pull‐down experiments followed by a kinase assay. For these experiments, GST–Myt1 was first coupled to glutathione–Sepharose beads and then incubated with Xenopus egg extracts. The beads were recovered from the extracts, washed and then incubated in a kinase reaction with [γ‐32P]ATP and Mg2+. The phosphorylated proteins were finally analysed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. We found that protein kinases from the extracts were able to bind to and efficiently phosphorylate the GST–Myt1 fusion protein (Figure 2, lane 5 in upper panel). Moreover, the electrophoretic mobility of the GST–Myt1 recombinant protein shifted upwards upon phosphorylation in the pull‐downs (Figure 2, lanes 4 and 5 in lower panel). We also detected in the GST–Myt1 pull‐downs additional phosphorylated bands of ∼34 and 90 kDa (Figure 2, arrowheads in upper panel). In the same experiments, GST–Wee1 was also phosphorylated but more weakly than GST–Myt1 (Figure 2, lane 3 in upper panel), although some variability was observed depending on the extracts. Moreover, we could not detect any significant size shift of the GST–Wee1 recombinant protein upon phosphorylation in pull‐downs (Figure 2, lanes 2 and 3 in lower panel).

Figure 10

Identification of protein kinase activities in egg extracts that bind to and phosphorylate GST–Myt1 and GST–Wee1 in pull‐downs. Bacterially produced GST (lane 1), GST–Wee1 (lane 3) and GST–Myt1 (lane 5) proteins were incubated with egg extracts, recovered by centrifugation, incubated with [γ‐32P]ATP and analysed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Purified GST–Wee1 (lane 2) and GST–Myt1 (lane 4) were also incubated with [γ‐32P]ATP and analysed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in parallel. The positions where the two purified recombinant proteins run are indicated. Arrowheads indicate two additional bands of ∼34 and 90 kDa which are phosphorylated in GST–Myt1 pull‐downs (lane 5). The upper panel shows an autoradiograph and the lower panel the same gel stained with Coomassie Blue.

p34 cdc2 ‐dependent and independent kinase activities can phosphorylate Myt1

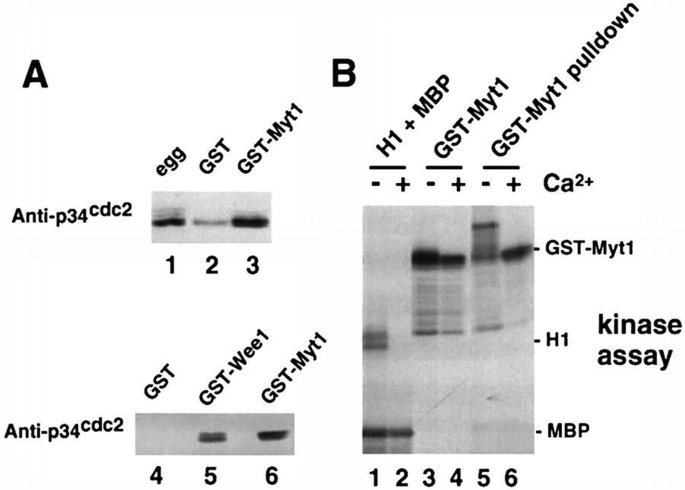

Many regulatory and structural proteins become phosphorylated or hyperphosphorylated during M‐phase, and p34cdc2/cyclin complexes are known to play an important role in these phosphorylations. To investigate whether p34cdc2 could be detected in GST–Myt1 pull‐downs, we analysed, by immunoblot with anti‐p34cdc2 antibodies, GST and GST–Myt1 pull‐downs prepared from Xenopus egg extracts. We found that in GST–Myt1 pull‐downs there was significantly more p34cdc2 than in those with GST alone (Figure 3A, compare lanes 2 and 4 with lanes 3 and 6, respectively), indicating that p34cdc2 can associate specifically either directly or indirectly with the C‐terminal regulatory region of Myt1. We also found p34cdc2 associated with GST–Wee1 pull‐downs (Figure 3A, lane 5).

Figure 11

p34cdc2 binds to Myt1. (A) Egg extracts (lane 1) and either GST (lanes 2 and 4), GST–Myt1 (lanes 3 and 6) or GST–Wee1 (lane 5) pull‐downs of the extracts were analysed by immunoblotting with anti‐p34cdc2 antibodies. (B) CSF‐arrested egg extracts were incubated in the presence (lanes 2, 4 and 6) or absence (lanes 1, 3 and 5) of Ca2+ for 30 min and then used for in vitro kinase assays using as substrates either histone H1 + MBP (lanes 1 and 2) or GST–Myt1 (lanes 3 and 4). Aliquots of the extracts were also used for GST–Myt1 pull‐downs (lanes 5 and 6) and then incubated with [γ‐32P]ATP and analysed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography.

To investigate the possible connection between p34cdc2/cyclin B and the kinase activity responsible for GST–Myt1 phosphorylation in egg extracts, we used Ca2+‐treated egg extracts. Treatment of cytostatic factor (CSF)‐arrested egg extracts with Ca2+ triggers cyclin B degradation, leading to MPF inactivation after 20–30 min as indicated by the absence of H1 kinase activity in the extracts (Figure 3B, lane 2). These H1 kinase‐negative egg extracts can still phosphorylate GST–Myt1, albeit less efficiently than the untreated CSF‐arrested egg extracts (Figure 3B, lanes 3 and 4). Moreover, in the Ca2+‐treated extracts, there is still a kinase activity that can bind to and phosphorylate GST–Myt1 in pull‐down experiments, but interestingly in this case the electrophoretic mobility of the GST–Myt1 protein does not shift as it does in the pull‐downs from CSF‐arrested egg extracts (Figure 3B, lanes 5 and 6). We conclude from this experiment that there are at least two protein kinase activities that can bind to and phosphorylate the C‐terminal regulatory region of Myt1 in vitro. One of the kinase activities is dependent on MPF and may be either p34cdc2/cyclin B or another p34cdc2/cyclin complex. The other protein kinase activity can bind to and phosphorylate Myt1 independently of MPF activity.

To gain more information on this MPF‐independent kinase activity that phosphorylates Myt1, we carried out in‐gel kinase assays using GST–Myt1 as a substrate. As shown in Figure 4A, both in egg extracts (lane 3) and in lysates prepared from progesterone‐matured oocytes (lane 2), we detected a protein kinase activity of ∼90 kDa which can phosphorylate GST–Myt1 upon renaturation in the gel. This activity, however, was not detected in lysates prepared from unstimulated oocytes arrested in G2 (lane 1). A protein kinase activity of 90 kDa was also strongly enriched in GST–Myt1 pull‐downs prepared from egg extracts when compared with the same pull‐downs using GST alone (∼12‐fold increase by PhosphorImager quantification; Figure 4A, compare lanes 5 and 6). In addition, we detected in GST–Myt1 pull‐downs another kinase activity of 50–60 kDa (Figure 4A, dot), but we do not know at present whether this activity is related to the 90 kDa activity or corresponds to a totally different protein kinase. When a duplicate of these samples was analysed in gels cast with GST alone, we could detect a kinase of ∼90 kDa which was able to renature, and presumably autophosphorylate, only in the GST–Myt1 pull‐downs, but not in any of the other samples (Figure 4A, arrowhead in lower panel). This observation is consistent with the idea that the 90 kDa kinase that phosphorylates Myt1 is enriched in GST–Myt1 pull‐downs, and confirms the previous detection of a phosphorylated band of 90 kDa in kinase assays using GST–Myt1 pull‐downs (Figure 2, lane 5 in upper panel).

Figure 2

A 90 kDa protein kinase binds to and phosphorylates Myt1. In‐gel kinase assays using as substrates GST–Myt1 (A, upper), GST–Wee1 (B, upper) or GST alone (A and B, lower). (A) Control, G2‐arrested oocyte lysates (lane1), progesterone‐matured oocyte lysates (lane 2), egg extracts (lane 3), purified GST–Myt1 (lane 4), GST (lane 5) and GST–Myt1 (lane 6) pull‐downs from egg extracts. (B) GST (lane 1), GST–Wee1 (lane 2) and GST–Myt1 (lane 3) pull‐downs from egg extracts. The arrowheads and the dot indicate kinase activities of 90 and 50–60 kDa, respectively.

As a control, we performed in‐gel kinase assays using GST–Wee1 polymerized in the gel. We observed that the 90 kDa protein kinase activity that binds to GST–Myt1 pull‐downs did not phosphorylate GST–Wee1 (Figure 4B, lane 3 in upper panel). Moreover, using a gel with GST alone, we confirmed that the GST–Myt1‐associated 90 kDa protein kinase is able to renature and autophosphorylate in the gel (Figure 4B, arrowhead in lower panel) but does not bind to GST–Wee1 (Figure 4B, lane 2), nor did we detect any protein kinase activity that is able to renature and phosphorylate GST–Wee1 (Figure 4B, lane 2 in upper panel).

p90 rsk strongly associates with Myt1

The protein kinase p90rsk is activated during Xenopus oocyte maturation at the same time as MAPK (Nebreda et al., 1993a; Hsiao et al., 1994). Thus, we decided to investigate the connection between p90rsk and the 90 kDa protein kinase that associates with and phosphorylates the C‐terminus of Myt1.

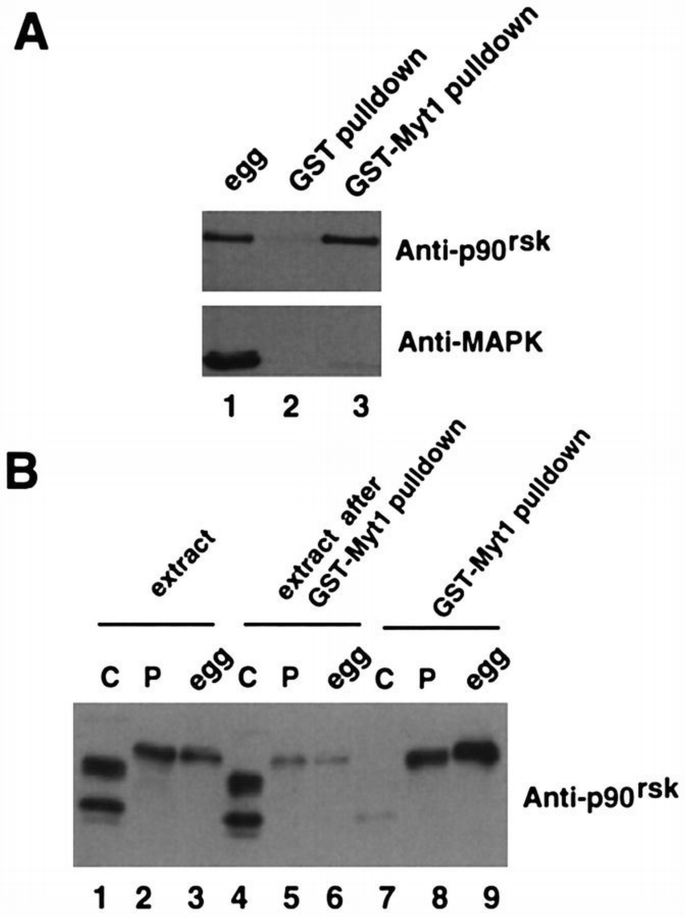

By immunoblotting using anti‐p90rsk‐specific antibodies, we found that p90rsk can be detected specifically in GST–Myt1 pull‐downs prepared from Xenopus egg extracts but not in the pull‐downs prepared with GST alone (Figure 5A, p90rsk). In contrast, the p42Mpk1 MAPK is not present at detectable levels in the same GST–Myt1 pull‐downs (Figure 5A, MAPK). Moreover, the C‐terminus of Myt1 associates more strongly with the active and hyperphosphorylated p90rsk present either in egg extracts (Figure 5B, lane 9) or in lysates prepared from progesterone‐matured oocytes (Figure 5B, lane 8) than with the inactive and hypophosphorylated p90rsk present in lysates from G2‐arrested oocytes (Figure 5B, lane 7).

Figure 3

p90rsk binds to Myt1. (A) Egg extracts (lane 1) and either GST (lane 2) or GST–Myt1 (lane 3) pull‐downs of the extracts were analysed by immunoblotting with both anti‐p90rsk and anti‐Mpk1 MAPK antibodies. (B) GST–Myt1 pull‐downs prepared from G2‐arrested oocyte lysates (lane 7), progesterone‐matured oocyte lysates (lane 8) or egg extracts (lane 9) were analysed by immunoblotting with anti‐p90rsk antibodies. The extracts before (lanes 1–3) and after the GST pull‐downs (lanes 4–6) were also analysed in the same immunoblot.

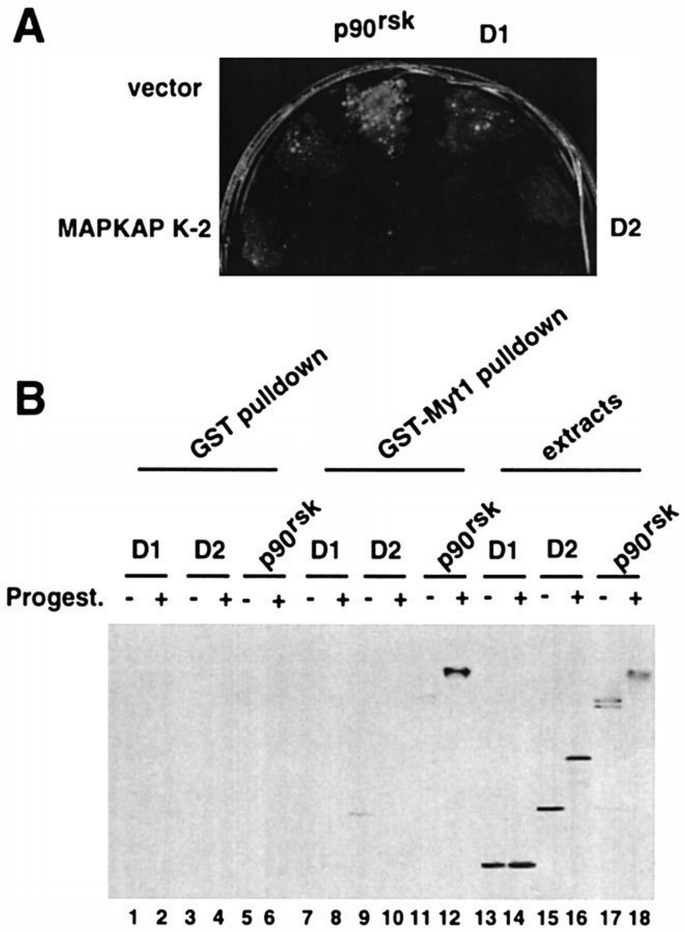

p90rsk is an unusual protein kinase in that it contains two catalytic (kinase) domains: the N‐terminal D1 domain is related to protein kinase A (PKA) and p70 S6K, while the C‐terminal D2 domain is related to the γ‐subunit of phosphorylase kinase (Jones et al., 1988). To characterize further the association between p90rsk and the C‐terminus of Myt1, we expressed both proteins in a yeast two‐hybrid system (Figure 6A). We found that Myt1 and p90rsk can also associate in this assay. Moreover, the association between p90rsk and Myt1 was only detected with the full‐length p90rsk; neither the D1 nor the D2 kinase domain alone were able to bind to the C‐terminus of Myt1. MAPKAP K‐2, a kinase that also can be phosphorylated and activated by MAPK in vitro (Stokoe et al., 1992), did not associate with Myt1. These results strongly suggest a direct interaction between p90rsk and the C‐terminus of Myt1 in yeast. Interestingly, other p90rsk‐interacting proteins such as the p42Mpk1 MAPK can interact in yeast both with the full‐length p90rsk and with the D2 kinase domain alone (A.‐C.Gavin and A.R.Nebreda, unpublished results). Association between the C‐terminus of Myt1 and full‐length p90rsk, but not the D1 or the D2 kinase domain, was also detected by expressing these proteins in Xenopus oocytes. In vitro transcribed mRNAs encoding either full‐length p90rsk or the D1 and D2 kinase domains were microinjected into oocytes and, after overnight incubation to allow for expression of the proteins, the corresponding oocyte lysates were used for GST–Myt1 pull‐downs. The results of this experiment shown in Figure 6B confirm that Myt1 associates more strongly with the active, hyperphosphorylated p90rsk than with the hypophosphorylated form.

Figure 4

Myt1 interacts in yeast and in Xenopus oocytes with full‐length p90rsk but not the D1 or D2 kinase domains independently. (A) Saccharomyces cerevisiae α cells expressing the Gal4 DNA‐binding domain fused in‐frame to the C‐terminal half of Myt1 were mated with S.cerevisiaea cells expressing the Gal4 activation domain either alone (vector) or fused in‐frame to MAPKAP K‐2, full‐length p90rsk, D1 kinase domain alone or D2 kinase domain alone, as indicated. Positive interactions were selected by plating the cells on medium lacking histidine. The five mating cultures grew to the same extent on medium supplemented with histidine. (B) In vitro transcribed mRNAs encoding myc‐tagged full‐length p90rsk or either myc‐tagged D1 or D2 kinase domains alone were injected into Xenopus oocytes which, after overnight incubation, were either left untreated (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 and 17) or matured by progesterone stimulation (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16 and 18). Total lysates prepared from these oocytes (lanes 13–18) together with GST pull‐downs (lanes 1–6) and GST–Myt1 pull‐downs (lanes 7–12) obtained from the same oocyte lysates were analysed by immunoblot with anti‐myc antibodies.

p90 rsk phosphorylates Myt1

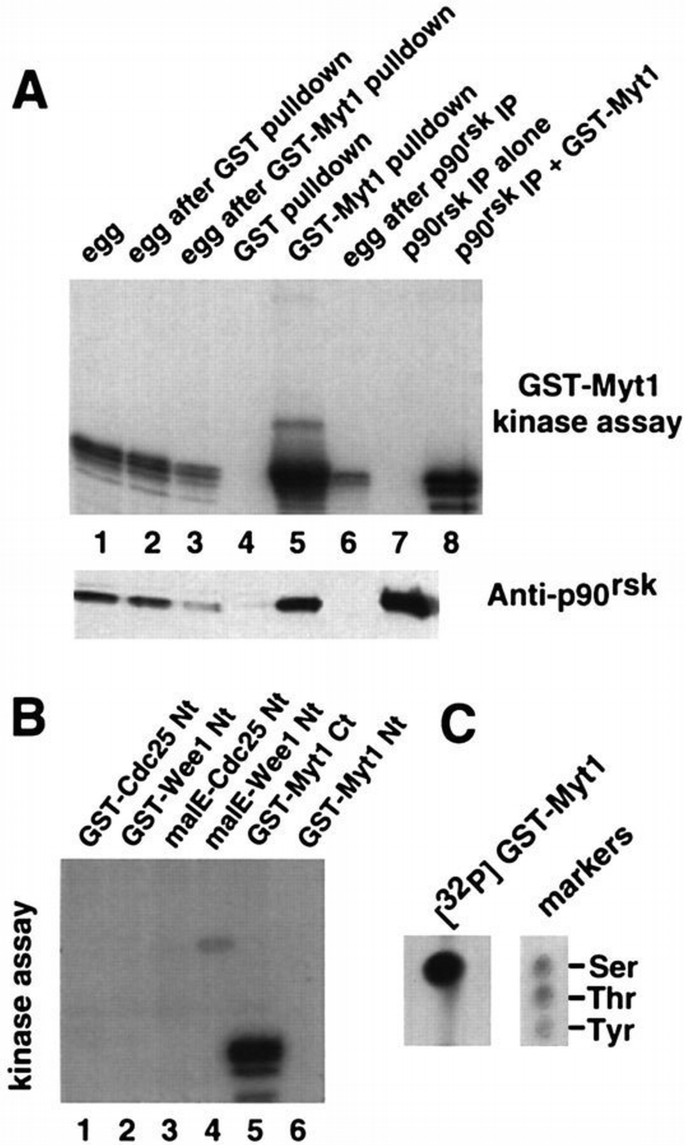

We next investigated whether p90rsk can phosphorylate the C‐terminus of Myt1. Immunoprecipitates prepared from egg extracts with anti‐p90rsk‐specific antibodies can phosphorylate exogenously added GST–Myt1 efficiently in vitro (Figure 7A, lane 8). Moreover, the Myt1‐phosphorylating kinase activity in the egg extracts can be immunodepleted using p90rsk antibodies (Figure 7A, compare lane 6 with lanes 1 and 2). As expected, GST–Myt1 pull‐downs can also phosphorylate exogenously added GST–Myt1 efficiently (Figure 7A, lane 5). In addition, a significant reduction in Myt1‐phosphorylating activity in the extract was observed following GST–Myt1 pull‐downs (Figure 7A, lane 3). When the same set of samples was analysed by immunoblot with anti‐p90rsk antibodies (Figure 7A, lower panel), we found that following GST–Myt1 pull‐downs the total amount of p90rsk in the extract was strongly reduced (Figure 7A, compare lanes 2 and 3 in the lower panel). This suggests a strong interaction between the C‐terminus of Myt1 and p90rsk, which would allow for the almost quantitative removal of p90rsk from the egg extract. We then analysed Xenopus egg extracts, fractionated using Mono Q chromatography, by immunoblot with anti‐p90rsk antibodies, and found that the fractions where p90rsk was detected overlapped with the major peak of kinase activity phosphorylating GST–Myt1 in vitro (data not shown).

Figure 5

p90rsk phosphorylates Myt1 on serine residues. (A) Upper panel: in vitro kinase assay using GST–Myt1 as a substrate (except for lane 7 where no substrate was added). Lane 1, egg extracts; lane 2, egg extracts after GST pull‐down; lane 3, egg extracts after GST–Myt1 pull‐down; lane 4, GST pull‐down from egg extracts; lane 5, GST–Myt1 pull‐down from egg extracts; lane 6, egg extracts after p90rsk immunoprecipitation; lanes 7 and 8, p90rsk immunoprecipitates from egg extracts incubated alone or in the presence of GST–Myt1, respectively. Lower panel: immunoblot with anti‐p90rsk antibodies of the same samples. (B) In vitro kinase assay using p90rsk immunoprecipitates from egg extracts and as a substrate either GST–Cdc25 Nt (lane 1), GST–Wee1 Nt (lane 2), malE–Cdc25 Nt (lane 3), malE–Wee1 Nt (lane 4), GST–Myt1 Ct (lane 5) or GST–Myt1 Nt (lane 6), as indicated. (C) GST–Myt1 was in vitro phosphorylated by p90rsk immunoprecipitates in the presence of [γ‐32P]ATP and then subjected to phosphoamino acid analysis.

To assess the specificity of p90rsk for the C‐terminus of Myt1, we investigated the ability of p90rsk immunoprecipitates to phosphorylate GST fused to the N‐terminus of Myt1 (Myt Nt). GST–Myt1 Nt was not phosphorylated by p90rsk_in vitro_ (Figure 7B, lane 6). We also used recombinant proteins containing the N‐terminal regulatory regions of either Wee1 or Cdc25C, but neither was phosphorylated significantly by p90rsk_in vitro_ (Figure 7B, lanes 1–4). Phosphoamino acid analysis of in vitro phosphorylated GST–Myt1 showed that phosphorylation by p90rsk only involves serine residues (Figure 7C), consistent with the known substrate specificity of p90rsk (Leighton et al., 1995).

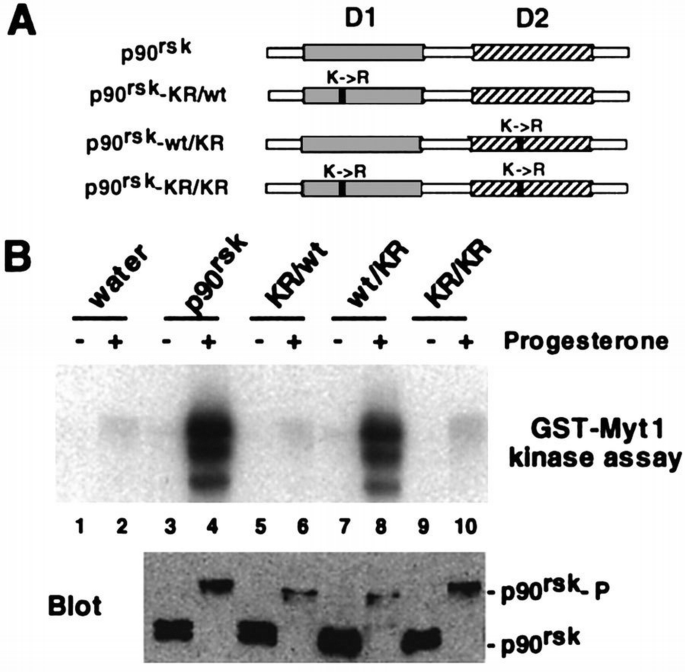

To investigate which of the two p90rsk kinase domains is responsible for Myt1 phosphorylation, mRNAs encoding myc‐tagged p90rsk proteins mutated in either one or both domains (Figure 8A) were microinjected into Xenopus oocytes. The expressed p90rsk mutant proteins were then recovered by immunoprecipitation (Figure 8B, lower panel) and tested for their ability to phosphorylate GST–Myt1 in vitro (Figure 8B, upper panel). As for the endogenous p90rsk present in oocytes, we found that activation of the myc‐tagged p90rsk required that the oocytes are first stimulated by progesterone treatment (Figure 8B, lanes 3 and 4). Moreover, mutation of both p90rsk kinase domains (D1 and D2) totally abolished the activity of p90rsk in progesterone‐treated oocytes (Figure 8B, lane 10). However, mutation of the D2 kinase domain alone only slightly reduced the activity of p90rsk on GST–Myt1 (Figure 8B, lane 8), whereas mutation of only D1 totally impaired the ability of p90rsk to phosphorylate GST–Myt1 in vitro (Figure 8B, lanes 6). This is consistent with results published for chicken Rsk2 and rat p90rsk1 which showed that the D1 kinase domain is required for the phosphorylation of exogenous substrates (Leighton et al., 1995; Fisher and Blenis, 1996). These results together with the in‐gel kinase assay strongly suggest that the activity phosphorylating Myt1 is p90rsk itself rather than a p90rsk‐associated protein kinase.

Figure 6

The D1 but not the D2 kinase domain of p90rsk is required for phosphorylation of Myt1. (A) Schematic representation of the lysine to arginine mutations introduced in p90rsk. (B) In vitro transcribed mRNAs encoding the myc‐tagged p90rsk mutants were injected into Xenopus oocytes which then were either left untreated (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9) or matured by progesterone stimulation (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10). The p90rsk proteins expressed in the oocytes were recovered by immunoprecipitation with anti‐myc antibodies and the immunoprecipitates were then used in kinase assays with GST–Myt1 (upper panel). An immunoblot with anti‐myc antibodies of the same samples is shown in the lower panel and the positions where p90rsk and the hyperphosphorylaled p90rsk (p90rsk‐P) run are indicated.

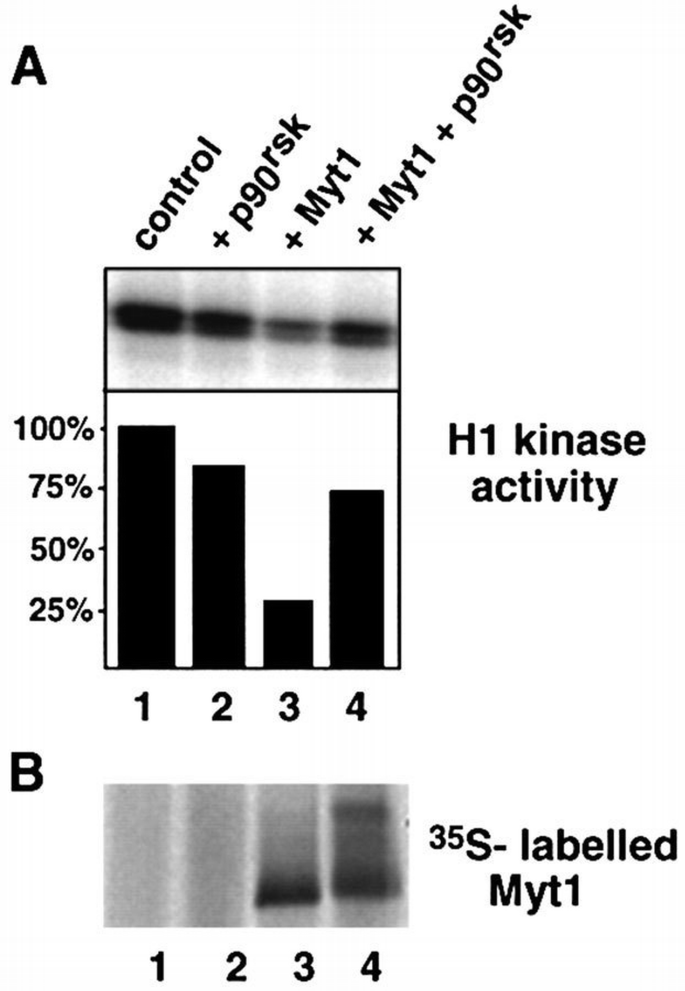

p90 rsk inactivates Myt1

To test the effect of phosphorylation by p90rsk on Myt1 activity, we expressed myc‐tagged Myt1 in reticulocyte lysate in the presence of microsomal membranes and then immunoprecipitated the Myt1 protein with anti‐myc antibodies. The immunopurified Myt1 was able to inhibit the histone H1 kinase activity of p34cdc2/cyclin B1 complexes purified from baculovirus‐infected insect cells (Figure 9A, lanes 1 and 3). The inhibition was between 45 and 75% using as a reference the activity of p34cdc2/cyclin B1 complexes incubated with anti‐myc immunoprecipitates prepared from reticulocyte lysates not expressing Myt1. Interestingly, pre‐incubation of Myt1 immunocomplexes with active p90rsk significantly reduced the ability of Myt1 to inhibit the kinase activity of p34cdc2/cyclin B1 complexes (Figure 9A, lanes 3 and 4). Active p90rsk alone had essentially no effect on the kinase activity of p34cdc2/cyclin B1 complexes (Figure 9A, lanes 1 and 2). We also found that the down‐regulation of Myt1 inhibitory activity upon incubation with active p90rsk correlated with an upward shift of the electrophoretic mobility of the Myt1 protein (Figure 9B, lanes 3 and 4). These results show that p90rsk‐induced phosphorylation of Myt1 inhibits its activity towards p34cdc2/cyclin B complexes. In contrast, in parallel assays, we have not been able to detect down‐regulation by p90rsk of the inhibitory activity of myc‐tagged Wee1 immunopurified from reticulocyte lysates (data not shown).

Figure 7

p90rsk down‐regulates Myt1 activity. (A) H1 kinase activity of p34cdc2/cyclin B1 complexes which were pre‐incubated with control immunoprecipitates (lanes 1 and 2) or immunopurified Myt1 (lanes 3 and 4) either in the absence (lanes 1 and 3) or presence (lanes 2 and 4) of active p90rsk. The phosphorylation reactions were analysed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography, and the results were quantified using a PhosphorImager. We observed inhibition of Myt1 activity by p90rsk in four independent experiments. (B) The 35S‐labelled Myt1 protein in the same samples: control (lane 1), p90rsk (lane 2), Myt1 immunoprecipitates (lane 3), Myt1 immunoprecipitates + p90rsk (lane 4).

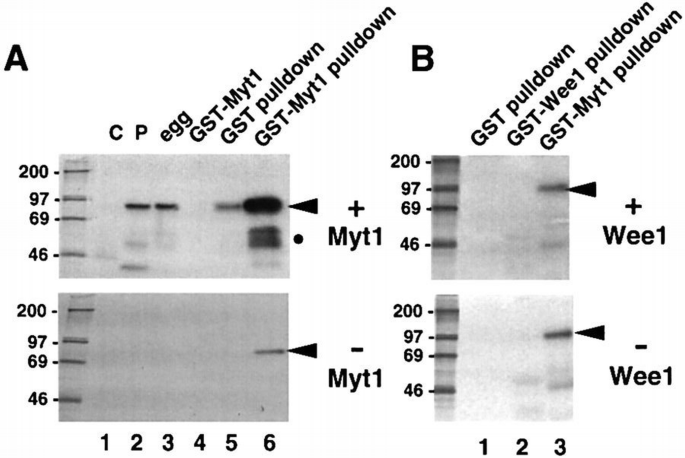

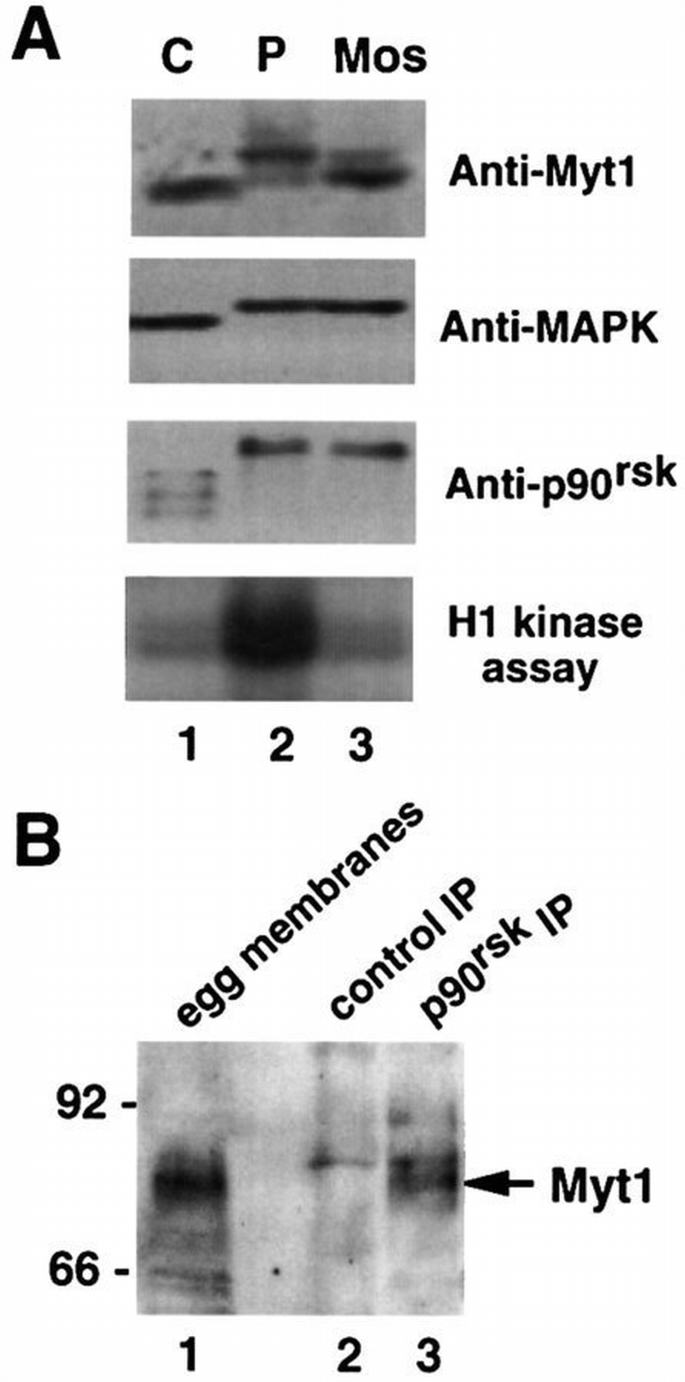

Endogenous Myt1 is phosphorylated during maturation and associates with p90 rsk in mature oocytes

Our results indicate that inhibition of Myt1 kinase activity may have an important role in oocyte maturation. To obtain further support for this hypothesis, we investigated the status of endogenous Myt1 in oocytes. We found that Myt1 protein is present in G2‐arrested oocytes (Figure 10A, lane 1) in contrast to Wee1 (Murakami and Vande Woude, 1998). Moreover, the electrophoretic mobility of the endogenous Myt1 protein is reduced in mature oocytes, consistent with the protein being hyperphosphorylated (and inactivated) during oocyte maturation (Figure 10A lane 2). To investigate whether the MAPK–p90rsk cascade has an effect on endogenous Myt1, oocytes were injected with Mos mRNA and then incubated for 4 h. Under these conditions where MAPK and p90rsk are activated but MPF is not, the band corresponding to endogenous Myt1 protein also shifted upwards, although the shift was less pronounced than in mature oocytes (Figure 10A, lane 3). These results show that the MAPK–p90rsk cascade can trigger some Myt1 phosphorylation in the absence of MPF activity and that in Mos‐injected oocytes this phosphorylation precedes the activation of pre‐MPF.

Figure 8

The endogenous Myt1 is phosphorylated during oocyte maturation and associates with p90rsk in mature oocytes. (A) Membrane fractions (equivalent to ∼30 oocytes) were isolated from G2‐arrested oocytes (lane 1), oocytes matured by incubation with progesterone for 16 h (lane 2) or oocytes injected with in vitro transcribed Mos mRNA and incubated for 4 h (lane 3) and then analysed by immunoblot with anti‐Myt1 antibodies. Aliquots of the same total lysates (equivalent to about one oocyte) before membrane purification were either used for H1 kinase assays or analysed by immunoblot with anti‐MAPK and anti‐p90rsk antibodies, as indicated. (B) Egg extracts (300 μl) were immunoprecipitated using either control (lane 2) or anti‐p90rsk (lane 3) antibodies and then analysed by immunoblot with anti‐Myt1 antibodies. Membrane fractions isolated from 50 μl of egg extracts were analysed in parallel (lane 1). The arrow indicates a band of ∼80 kDa which is recognized by the affinity‐purified anti‐Myt1 antibodies and is present both in isolated membrane fractions and in p90rsk immunoprecipitates.

We next investigated whether a complex between the endogenous Myt1 and p90rsk is present in mature oocytes. Using anti‐Myt1 antibodies, we detected a band of ∼80 kDa in immunoblots prepared with the membrane fraction isolated from egg extracts (Figure 10B, lane 1). A band of the same electrophoretic mobility was also detected by the anti‐Myt1 antibodies in p90rsk immunoprecipitates prepared from egg extracts (Figure 10B, lanes 3 arrow), but not in control immunoprecipitates prepared in parallel (Figure 10B, lanes 2). These results suggest that the hyperphosphorylated Myt1 protein forms a complex with p90rsk in mature oocytes.

Discussion

We have shown that the C‐terminal, non‐catalytic region of the p34cdc2 inhibitory kinase Myt1 can be phosphorylated by protein kinases which are present in M‐phase egg extracts. In parallel experiments, we do not detect significant phosphorylation of the N‐terminal half of Myt1 which includes the kinase domain (data not shown). Since Myt1 hyperphosphorylation during M‐phase correlates with decreased activity of the enzyme (Mueller et al., 1995b), our results suggest a correlation between phosphorylation of the C‐terminus of Myt1 and down‐regulation of Myt1 kinase activity. We have identified at least two protein kinases that can bind to and phosphorylate the non‐catalytic domain of Myt1. One of them is dependent on MPF activity and may be p34cdc2/cyclin B or another p34cdc2/cyclin complex since we detected p34cdc2 in GST–Myt1 pull‐downs. This suggests that phosphorylation of Myt1 by p34cdc2/cyclin B (or a downstream kinase) may be involved in a feedback loop of autoamplification, as has been proposed for Cdc25C and Wee1 (Hoffmann et al., 1993; Mueller et al., 1995a). The other kinase activity is p90rsk which can bind to and phosphorylate the C‐terminus of Myt1 independently of MPF activity.

p90 rsk associates with and phosphorylates Myt1

The interaction between p90rsk and the C‐terminus of Myt1 is strong enough to allow bacterially produced GST–Myt1 to almost deplete the endogenous p90rsk from Xenopus egg extracts. In contrast, GST–Myt1 does not bind detectable amounts of MAPK from egg extracts. We also found association between p90rsk and the C‐terminus of Myt1 in a yeast two‐hybrid system, which strongly suggests a direct interaction between the two proteins. Moreover, the interaction of p90rsk and Myt1 is only detected when the full‐length p90rsk is used; neither of the two p90rsk kinase domains D1 or D2 alone interact with Myt1. This is in contrast to the ability of MAPK to interact with the D2 kinase domain of p90rsk alone, and suggests that MAPK and Myt1 probably interact with different regions of p90rsk. Finally, the association between p90rsk and Myt1 is enhanced by the hyperphosphorylation that normally accompanies the activation of p90rsk, which is consistent with the observation that inactive p90rsk is associated mostly with MAPK and supports the idea that Myt1 may be a relevant substrate for p90rsk (see below). Our results also indicate that the requirements for binding to p90rsk are very different for MAPK (a p90rsk activator) and Myt1 (a p90rsk substrate).

The specificity of the phosphorylation of the C‐terminal region of Myt1 by p90rsk is supported by the observation that p90rsk efficiently phosphorylates neither the N‐terminus of Myt1 nor the regulatory regions of either Cdc25C or Wee1. Moreover, as reported for other p90rsk substrates (Leighton et al., 1995; Fisher and Blenis, 1996), the ability of p90rsk to phosphorylate Myt1 is only slightly affected by mutation of the D2, C‐terminal kinase domain of p90rsk, but it is totally impaired by mutation of the D1 N‐terminal kinase domain.

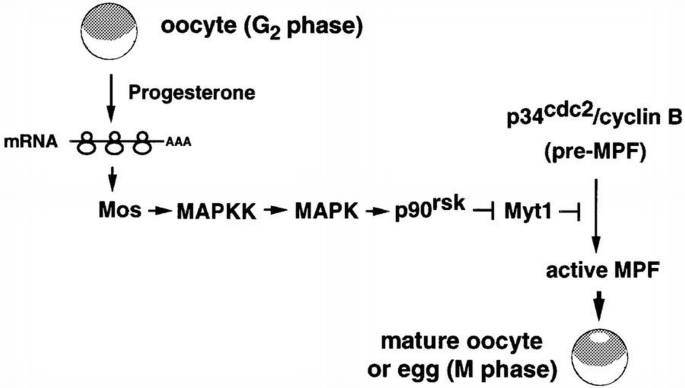

A link between MAPK and MPF during oocyte maturation

The strong and specific interaction between p90rsk and Myt1 as well as the ability of p90rsk to phosphorylate Myt1 suggest a functional connection between the two proteins. This is supported further by the observation that phosphorylation by p90rsk interferes with the inhibitory activity of Myt1 on p34cdc2/cyclin B1 complexes in vitro. This result suggests a direct link between the MAPK pathway and the activation of p34cdc2/cyclin B (MPF) during oocyte maturation (Figure 11). At the same time, this is consistent with the work showing that MAPK down‐regulates a factor which can inactivate MPF (Abrieu et al., 1997). Our model implies that p90rsk is an important mediator of the triggering activity of MAPK in oocyte maturation. Several reasons, however, make it difficult to demonstrate directly a role for p90rsk in oocyte maturation. First, both MAPK and p90rsk are always activated at the same time in Xenopus oocytes, which is probably related to the fact that they are associated in their inactive forms. Secondly, so far it has not been possible to activate p90rsk independently of MAPK and there are no constitutively active p90rsk mutants available. Finally, inhibitors of p90rsk activity in vitro (Alessi, 1997) do not appear to be effective when used in intact Xenopus oocytes (unpublished observations).

Figure 9

A pathway to link the activation of MAPK and p34cdc2/cyclin B during oocyte maturation. In G2‐arrested oocytes, progesterone stimulates unidentified signalling pathways that lead to the translation of maternal mRNAs including Mos. Accumulation of the protein kinase Mos induces the activation of MAPK, via MAPK kinase, and MAPK in turn activates p90rsk. Our results suggest that p90rsk down‐regulates the p34cdc2 inhibitory kinase Myt1, thus leading to the activation of p34cdc2/cyclin B (pre‐MPF) and entry into M‐phase of meiosis. For clarity, feedback loops and other proteins that may also have a role in triggering meiotic maturation are omitted from the scheme.

Another implication of our model is that Myt1 may be the activity responsible for maintaining the pre‐formed p34cdc2/cyclin B complexes in their inactive state (pre‐MPF). Consistent with this possibility, we find that Myt1 protein is present in G2‐arrested oocytes, in contrast to Wee1 which is only detected upon progesterone stimulation (Murakami and Vande Woude, 1998). We also find that during oocyte maturation the electrophoretic mobility of the endogenous Myt1 protein shifts upwards, which is most likely due to hyperphosphorylation. As reduced electrophoretic mobility of Myt1 has been shown to correlate with down‐regulation of Myt1 activity (Mueller et al., 1995b; Booher et al., 1997), our results suggest that Myt1 is active in G2‐arrested oocytes and later down‐regulated during oocyte maturation. Moreover, we detected partial phosphorylation of the endogenous Myt1 protein under conditions where the MAPK–p90rsk pathway is activated but MPF is not. This is the case, for example, in Mos‐injected oocytes, where activation of MAPK–p90rsk and phosphorylation of Myt1 precede the activation of pre‐MPF. We have also found that endogenous Myt1 and p90rsk form a complex in mature oocytes. These results, together with the experiments showing phosphorylation and inactivation of Myt1 by p90rsk_in vitro_, indicate that p90rsk is an excellent candidate for triggering the inhibition of Myt1 kinase activity during oocyte maturation. However, it should be noted that human Myt1 is a substrate for p34cdc2/cyclin B1 complexes in vitro (Booher et al., 1997), and we have also shown that the C‐terminus of Xenopus Myt1 can interact either directly or indirectly with p34cdc2. Thus Myt1 regulation might require a multistep mechanism which could ensure the proper timing for inactivation of Myt1. This would be consistent with our observation that in M‐phase extracts, at least two protein kinases can phosphorylate the C‐terminus of Myt1.

In summary, our results indicate that down‐regulation of Myt1 activity by p90rsk phosphorylation is very likely to be of physiological relevance for the activation of MPF during progesterone‐induced oocyte maturation (Figure 11). We cannot rule out, however, that alternative pathways, leading for example to the up‐regulation of the Cdc25C phosphatase, may also be activated in parallel during the process. Further work is needed to elucidate fully the regulation of Myt1 function by phosphorylation and its contribution to the signalling pathways that trigger MPF activation and the meiotic maturation of Xenopus oocytes.

Materials and methods

cDNA cloning and manipulation

Xenopus Myt1 (Mueller et al., 1995b), Wee1 (Mueller et al., 1995a), Cdc25C (Kumagai and Dunphy, 1992) and p90rsk (Jones et al., 1988) were cloned from Xenopus oocyte and egg cDNA libraries by PCR using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) and oligonucleotides based on published sequences. Complete details of the oligonucleotides and PCR conditions will be provided upon request. All the constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

The N‐terminal half of Myt1 which includes the kinase domain (Myt1 Nt, amino acids 1–329) was cloned using a 5′ oligonucleotide designed to create a _Sma_I site in front of the first ATG and a 3′ oligonucleotide that introduced a stop codon at nucleotide 1011 followed by a _Sal_I site. The C‐terminal half of Myt1 which includes the transmembrane domain (Myt1 Ct, amino acids 322–518) was isolated using oligonucleotides designed to create a _Bam_HI site at nucleotide 990 and a S_al_I site downstream of the stop codon. Both PCR fragments were digested with the corresponding restriction endonucleases and cloned into the pGEX‐KG vector. To prepare the GST–Myt1 Ct recombinant protein, we generated a modified Myt1 Ct which lacks the transmembrane domain (Myt1 Ct2, amino acids 389–518) using an oligonucleotide that created a _Bam_HI site at nucleotide 1188. Myt1 Ct2 was also subcloned into the _Nde_I–_Sal_I sites of the yeast vector pAS2‐1 using an oligonucleotide designed to create a _Nde_I site at amino acid 389. Full‐length Myt1 was cloned using a 5′ oligonucleotide that introduced a _Nco_I site at the first ATG and a 3′ oligonucleotide that created a _Xho_I site downstream of the stop codon. The PCR product was cloned between the _Nco_I and _Xho_I sites of the FTX5 vector (provided by C.Hill, ICRF, London).

The N‐terminal, non‐catalytic half of Wee1 (Wee1 Nt, amino acids 6–209) was cloned using a 5′ oligonucleotide that created a _Bam_HI site at nucleotide 22 downstream of the first ATG and a 3′ oligonucleotide that introduced an _Eco_RI site at nucleotide 625. The PCR product was digested with _Bam_HI and _Eco_RI and inserted between the _Bam_HI and _Eco_RI sites of pGEX‐KG, in order to express the GST–Wee1 Nt protein. Wee1 Nt was also subcloned from pGEX‐Wee1 Nt into pMalc2 as a _Bam_HI–_Sal_I fragment to produce the malE–Wee1 Nt fusion protein.

The N‐terminal half of Cdc25C (Cdc25 Nt, amino acids 9–205) was cloned using a 5′ oligonucleotide that created a _Bcl_I site at nucleotide 22 downstream of the first ATG and a 3′ oligonucleotide based on the sequence of Cdc25 from nucleotides 672 to 645, downstream of the internal _Bam_HI site at position 609. The PCR product was digested with _Bcl_I and _Bam_HI and cloned into the _Bam_HI site of pGEX‐KG. Cdc25 Nt was also subcloned into pMalc2 by PCR from pGEX‐Cdc25 Nt using a 5′ oligonucleotide that reconstituted the _Bam_HI site at the _Bcl_I–_Bam_HI site and a 3′ oligonucleotide that eliminated the _Bam_HI site at position 609 and introduced immediately downstream a stop codon followed by a new _Bam_HI site. The PCR product was digested with _Bam_HI and cloned into the _Bam_HI site of pMalc2.

p90rsk was cloned using a 5′ oligonucleotide that introduced a _Nco_I site at the first ATG and a 3′ oligonucleotide that created an _Xho_I site downstream of the stop codon. The PCR products were cloned into the PCRII vector (Invitrogen) and analysed by DNA sequencing. One of the clones was found to be identical in sequence to the p90rsk α isoform described by Jones et al. (1988) and was chosen for further work. To subclone the N‐terminal (D1) and C‐terminal (D2) domains of p90rsk, PCRII‐p90rsk was digested with _Nco_I and _Xho_I and the 923 bp Nco_I–_NcoI fragment (D1) and 1279 bp _Nco_I–_Xho_I fragment (D2) were ligated into both pACT2 (Clontech) and FTX5. The full‐length p90rsk was also subcloned into the pACT2 and FTX5 vectors by digestion of PCRII‐p90rsk with _Xho_I followed by partial digestion with _Nco_I. Site‐directed mutagenesis to change the conserved lysine residues to arginine in the D1 (K94R) and D2 (K445R) catalytic domains was done by PCR using the QuikChange site‐directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Capped mRNAs were obtained from _Xba_I‐linearized FTX5 constructs using the MEGAscript in vitro transcription kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After LiCl precipitation, mRNAs were resuspended in 25 μl of diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)‐treated water and stored at −70°C. All proteins expressed from FTX5 constructs contained the myc epitope at the N‐terminus (Howell and Hill, 1997).

Bacterial expression and purification of GST and malE fusion proteins

Recombinant GST or malE fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli TG‐1 or in E.coli DE3. For the GST fusion proteins, fresh overnight LB‐ampicillin (100 μg/ml) cultures were diluted 10‐fold with fresh medium and incubated at 37°C until the _A_600 was 0.4–0.5. Induction was for 6 h at 23°C using 0.1 mM isopropyl‐β‐D‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The cells were harvested, washed with cold phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM benzamidine, 0.05% NP‐40 and 0.5 mg/ml lysozyme, for 30 min at 4°C. After sonication and centrifugation at 10 000 g for 15 min, the supernatant was mixed with glutathione–Sepharose (Pharmacia) for 30 min at 4°C. Beads were washed in lysis buffer containing neither NP‐40 nor lysozyme, and the GST fusion proteins were eluted with 10 mM glutathione in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). For the purification of malE fusion proteins, the E.coli cultures were obtained as above and induced with 0.1 mM IPTG. Bacterial pellets were lysed for 30 min at 4°C in 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF and 1 mg/ml lysozyme. The lysate was sonicated, and 1 mM DTT was added before centrifugation. The supernatants were incubated with amylose beads (New England Biolabs) for 30 min at 4°C and the beads were washed twice with PBS and once with 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT. The malE‐fused protein was eluted in the same buffer supplemented with 0.1 mM EDTA and 12 mM maltose. Fractions containing the purified GST or malE fusion proteins were dialysed overnight against 20–50 mM Tris, pH 7.5–8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 5% glycerol and stored in aliquots at −70°C.

Preparation and fractionation of egg extracts

CSF‐arrested egg extracts were prepared as described by Murray (1991). Ca2+ treatment was performed by the addition of 0.4 mM CaCl2 to the egg extracts followed by incubation at 25°C. For fractionation, the egg extracts were first diluted 1:10 in H1K buffer (80 mM β‐glycerophosphate, pH 7.5, 20 mM EGTA, 15 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF or AEBSF, 2.5 mM benzamidine and 2 μg/ml each of leupeptin and aprotinin) and ultracentrifuged at 100 000 g for 90 min. Ammonium sulfate was added to the supernatant to 35% saturation and, after incubation for 30 min at 4°C, the solution was centrifuged at 10 000 g for 30 min. The pellet was resuspended in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, dialysed and applied to an anion exchange column of Mono Q HR 5/5 (Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4. The column was developed with a 20 ml linear salt gradient up to 0.5 M NaCl in equilibration buffer. The flow rate was 1 ml/min and fractions of 1 ml were collected and assayed for kinase activity or immunoblotting.

To prepare membrane fractions from eggs, 400 μl of concentrated CSF‐arrested extracts were centrifuged at 260 000 g for 90 min. The pellet was resuspended in 60 μl of 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.7, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM PMSF, 2.5 mM benzamidine, 1 μM calyculin A and 2 μg/ml each of leupeptin and aprotinin and stored at −70°C.

Oocyte maturation and mRNA expression

Meiotic maturation of Xenopus oocytes was induced by incubation of manually dissected oocytes with 5 μg/ml of progesterone (Sigma) in modified Barth's medium. For expression of myc‐tagged proteins, oocytes were microinjected with 50 nl of the in vitro transcribed mRNAs (diluted 1:5 in DEPC‐treated water) and maintained overnight at 18°C before progesterone treatment. For the preparation of lysates, oocytes were homogenized in 10 μl per oocyte of ice‐cold H1K buffer. The lysates were centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min and the cleared supernatants stored at −70°C. To prepare membrane fractions from oocytes, the low speed supernatants corresponding to 100 oocytes were centrifuged further at 260 000 g for 90 min. The pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of the same buffer as indicated above for egg extracts and stored at −70°C.

Kinase assays

Protein kinases normally were assayed in a final volume of 12 μl of H1K buffer containing 4 μl of egg extract (diluted 1:10) or oocyte lysate, 50 μM cold ATP, 2 μCi of [γ‐32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) and either 4 μg of histone H1 (Sigma), 3 μg of myelin basic protein (MBP, Sigma) or 1 μg of the GST or malE bacterially expressed fusion proteins. After 15 min at room temperature, the phosphorylation reactions were terminated by addition of sample buffer and were analysed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography.

Myc‐tagged p90rsk immunoprecipitates were assayed for 40 min at room temperature in a final volume of 15 μl of S6 kinase buffer (50 mM MOPS, pH 7.2, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM _p_‐nitrophenylphosphate, 0.1% Triton X‐100, 1 μM NaVO3, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 100 μM PMSF or AEBSF) containing 100 μM ATP, 5 μCi of [γ‐32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) and 0.4 μg of GST–Myt1.

For in‐gel kinase assays, proteins were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 10% Laemmli gels which were polymerized in the presence of 100 μg/ml of either GST–Myt1, GST–Wee1 or GST alone. After electrophoresis, the gels were processed following the protocol described by Peverali et al. (1996).

To assay Myt1 activity, myc‐tagged Myt1 protein was expressed from FTX5‐Myt1 using TNT reticulocyte lysate supplemented with canine pancreatic microsomal membranes as recommended by the supplier (Promega). After translation, the reticulocyte lysate (50 μl) was diluted 1:1 in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (see below) and then incubated for 2 h at 4°C with 10 μl of 9E10 anti‐myc antibody conjugated to agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). As a control, the same 9E10 antibody agarose conjugate was used to immunoprecipitate reticulocyte lysates which did not express Myt1. The Myt1 and the control immunocomplexes were washed three times in IP buffer, twice with kinase buffer (50 mM HEPES–KOH, pH 7.3, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 2.5 mM benzamidine, 1 μM calyculin A and 10 μg/ml each of leupeptin and aprotinin) and then incubated in 12 μl of kinase buffer containing 250 μM ATP and 6 μl of p34cdc2/cyclin B1 complexes prepared from baculovirus‐infected Sf9 cells as described by Kumagai and Dunphy (1997). After 30 min at room temperature, the activity of the p34cdc2/cyclin B1 complexes was assayed by adding 12 μl of kinase buffer containing 4 μg of histone H1 and 2 μCi of [γ‐32P]ATP, and incubating for a further 15 min at room temperature. The samples finally were boiled in sample buffer and analysed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. To determine the effect of p90rsk phosphorylation on Myt1 activity, the Myt1 immunocomplexes were pre‐incubated with active p90rsk for 30 min at room temperature in 12 μl of kinase buffer supplemented with 350 μM ATP. We observed down‐regulation of Myt1 activity using either active GST–p90Rsk1 fusion protein purified from mammalian cells (0.1 μg, provided by D.Alessi, MRC, Dundee, Scotland) or Xenopus p90rsk immunopurified from egg extracts as described below.

Immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation and GST pull‐down experiments

For immunoblotting, protein samples normally were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 15% Anderson gels (Nebreda et al., 1995) and then transferred to 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membranes using a semi‐dry blotting apparatus (Hoefer). Blocking was done in TTBS (25 mM Tris, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween‐20) containing 4% milk, and the antibodies were incubated in TTBS containing 1% milk. The monoclonal antibody 3E1 (provided by J.Gannon and T.Hunt, ICRF South Mimms) was used to detect p34cdc2 (Nebreda et al., 1995), and the rabbit antiserum 3297.1 prepared against the same C‐terminal peptide of the p42Erk2 MAPK as described by Leevers and Marshall (1992) was used for the Xp42/Mpk1 MAPK. p90rsk was detected using a purified anti‐Rsk1 goat antibody (C‐21‐G, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The 9E10 monoclonal antibody was used to detect myc‐tagged proteins. The anti‐Myt1 antibodies were prepared in rabbits against a keyhole limpet haemocyanin (KLH)‐coupled peptide corresponding to the C‐terminal end of Myt1 (CPRNLLGMFDDATEQ) and were affinity purified on GST–Myt1 Ct coupled to Affi‐Gel 10 (Bio‐Rad). In all cases, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)‐coupled secondary antibodies (Dakko) were used and the binding was detected using ECL (Amersham).

The endogenous p90rsk was immunoprecipitated from egg extracts using 5 μg of the anti‐Rsk1 antibody C‐21‐G pre‐bound to 10 μl of protein G–Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia). In a typical experiment, the antibody‐bound beads were washed in IP buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM EDTA, 20 mM NaF, 0.5–1% NP‐40, 100 μM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, 2.5 mM benzamidine, 10 μg/ml each of leupeptin and aprotinin and either 2 μM microcystin or 1 μM calyculin A) and then incubated for 2 h at 4°C in 100 μl of the 100 000 g supernantant from egg extracts (diluted 1:10). The immunocomplexes were washed twice with IP buffer and once with H1K buffer and then either used immediately for in vitro kinase assay as indicated above or analysed by immunoblot. To investigate the co‐immunoprecipitation of Myt1 and p90rsk, 300 μl of concentrated egg extracts were mixed 1:1 with IP buffer, left on ice for 20 min and then centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min. p90rsk immunocomplexes were prepared from the supernatant as described above and then analysed by immunoblot with affinity‐purified anti‐Myt1 antibodies.

For immunoprecipitation of myc‐tagged p90rsk expressed in oocytes, 3 μg of the anti‐myc antibody 9E10 were pre‐bound to 20 μl of protein G beads in IP buffer and then incubated for 2 h at 4°C in 70 μl of lysate prepared from oocytes expressing either wild‐type or mutant forms of p90rsk. The immunocomplexes were washed three times in IP buffer and once in S6 kinase buffer (see above) and then were used in kinase assays or analysed by immunoblotting.

For GST pull‐down experiments, 5–10 μg of the bacterially produced GST fusion proteins were pre‐bound to 20 μl of glutathione–Sepharose beads and then incubated in 80–100 μl of either oocyte lysates or the 100 000 g supernatant from egg extracts (diluted 1:10). After 2 h rocking at 4°C, the beads were washed three times with H1K buffer and then either used immediately for kinase assay as indicated above or analysed by immunoblot.

Phosphoamino acid analysis

GST–Myt1 was phosphorylated with p90rsk immunopurified from egg extracts as indicated above. After polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Immobilon, Millipore) and the band corresponding to GST–Myt1 was cut out. Phosphoamino acids were analysed by HCl hydrolysis of the protein followed by thin‐layer chromatography using standard procedures (Kamps, 1991).

Yeast transformation and mating

For analysis of protein interactions, yeast transformations were performed using the lithium/acetate protocol as recommended by Clontech. The constructs pAS2‐1‐Myt1 Ct2, pACT2‐p90rsk, pACT2‐D1 and pACT2‐D2 were prepared as indicated above. pACT2‐MAPKAP K‐2 was prepared by PCR using a rabbit MAPKAP K‐2 cDNA provided by P.Cohen (MRC, University of Dundee, Scotland). For mating, pAS2‐1 constructs were transformed into Y187 α cells (Clontech) and pACT2 constructs into Y190 a cells (Clontech). Both cell types were incubated together in 0.5 ml of YPD medium for ∼8 h and then 10 μl of the culture were plated on selective medium.

References

- Abrieu A, Dorée M and Picard A (1997) Mitogen‐activated protein kinase activation downregulates a mechanism that inactivates cyclin B–cdc2 kinase in G2‐arrested oocytes. Mol Biol Cell, 8, 249–261.

Google Scholar - Alcorta DA, Crews CM, Sweet LJ, Bankston L, Jones SW and Erikson RL (1989) Sequence and expression of chicken and mouse rsk: homologs of Xenopus laevis ribosomal S6 kinase. Mol Cell Biol, 9, 3850–3859.

Google Scholar - Alessi DR (1997) The protein kinase C inhibitors Ro318220 and GF109203X are equally potent inhibitors of MAPKAP kinase‐1β (Rsk‐2) and p70 S6 kinase. FEBS Lett, 402, 121–123.

Google Scholar - Alessi DR, Cuenda A, Cohen P, Dudley DT and Saltiel AR (1995) PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem, 270, 27489–27494.

Google Scholar - Atherton‐Fessler S, Liu F, Gabrielli B, Lee MS, Peng CY and Piwnica‐Worms H (1994) Cell cycle regulation of the p34cdc2 inhibitory kinases. Mol Biol Cell, 5, 989–1001.

Google Scholar - Barkoff A, Ballantyne S and Wickens M (1998) Meiotic maturation in Xenopus requires polyadenylation of multiple mRNAs. EMBO J, 17, 3168–3175.

Google Scholar - Booher RN, Holman PS and Fattaey A (1997) Human Myt1 is a cell cycle‐regulated kinase that inhibits cdc2 but not cdk2 activity. J Biol Chem, 272, 22300–22306.

Google Scholar - Chung J, Pelech SL and Blenis J (1991) Mitogen‐activated Swiss mouse 3T3 rsk kinases I and II are related to pp44mpk from sea star oocytes and participate in the regulation of pp90rsk activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 88, 4981–4985.

Google Scholar - Coleman TR and Dunphy WG (1994) Cdc2 regulatory factors. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 6, 877–882.

Google Scholar - Cyert MS and Kirschner MW (1988) Regulation of MPF activity in vitro. Cell, 53, 185–195.

Google Scholar - Dunphy WG and Kumagai A (1991) The cdc25 protein contains an intrinsic phosphatase activity. Cell, 67, 189–196.

Google Scholar - Erikson E and Maller JL (1986) Purification and characterization of a protein kinase from Xenopus eggs highly specific for ribosomal protein S6. J Biol Chem, 261, 350–355.

Google Scholar - Fisher T and Blenis J (1996) Evidence for two catalytically active kinase domains in pp90rsk. Mol Cell Biol, 16, 1212–1219.

Google Scholar - Gautier J and Maller JL (1991) Cyclin B in Xenopus oocytes: implications for the mechanism of pre‐MPF activation. EMBO J, 10, 177–182.

Google Scholar - Gautier J, Solomon MJ, Booher RN, Bazan JF and Kirschner MW (1991) cdc25 is a specific tyrosine phosphatase that directly activates p34cdc2. Cell, 67, 197–211.

Google Scholar - Gotoh Y, Masuyama N, Dell K, Shirakabe K and Nishida E (1995) Initiation of Xenopus oocyte maturation by activation of the mitogen‐activated protein kinase cascade. J Biol Chem, 270, 25898–25904.

Google Scholar - Haccard O, Lewellyn A, Hartley RS, Erikson E and Maller JL (1995) Induction of Xenopus oocyte meiotic maturation by MAP kinase. Dev Biol, 168, 677–682.

Google Scholar - Hoffmann I, Clarke PR, Marcote MJ, Karsenti E and Draetta G (1993) Phosphorylation and activation of human cdc25c by cdc2:cyclin B and its involvement in the self‐amplification of MPF at mitosis. EMBO J, 12, 53–63.

Google Scholar - Howell M and Hill CS (1997) XSmad2 directly activates the activin‐inducible, dorsal mesoderm gene XFKH1 in Xenopus embryos. EMBO J, 16, 7411–7421.

Google Scholar - Hsiao K, Chou S, Shin S and Ferrel J (1994) Evidence that inactive p42 mitogen‐activated protein kinase and inactive Rsk exist as a heterodimer in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 91, 5480–5484.

Google Scholar - Huang W, Kessler DS and Erikson RL (1995) Biochemical and biological analysis of Mek1 phosphorylation site mutants. Mol Biol Cell, 6, 237–245.

Google Scholar - Izumi T and Maller JL (1993) Elimination of cdc2 phosphorylation sites in the cdc25 phosphatase blocks initiation of M‐phase. Mol Biol Cell, 4, 1337–1350.

Google Scholar - Izumi T, Walker DH and Maller JL (1992) Periodic changes in phosphorylation of the Xenopus cdc25 phosphatase regulate its activity. Mol Biol Cell, 3, 927–939.

Google Scholar - Jones SW, Erikson E, Blenis J, Maller JL and Erikson RL (1988) A Xenopus ribosomal protein S6 kinase has two apparent kinase domains that are each similar to distinct protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 85, 3377–3381.

Google Scholar - Kamps MP (1991) Determination of phosphoamino acids composition by acid hydrolysis of protein blotted to immobilon. Methods Enzymol, 201, 21–27.

Google Scholar - Kanki JP and Donoghue DJ (1991) Progression from meiosis I to meiosis II in Xenopus oocytes requires de novo translation of the mos xe protooncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 88, 5794–5798.

Google Scholar - Kobayashi H, Minshull J, Ford C, Golsteyn R, Poon R and Hunt T (1991) On the synthesis and destruction of A‐ and B‐type cyclins during oogenesis and meiotic maturation in Xenopus laevis. J Cell Biol, 114, 755–765.

Google Scholar - Kornbluth S, Sebastian B, Hunter T and Newport J (1994) Membrane localization of the kinase which phosphorylates p34cdc2 on threonine 14. Mol Biol Cell, 5, 273–282.

Google Scholar - Kosako H, Gotoh Y and Nishida E (1994) Requirement for the MAP kinase kinase/MAP kinase cascade in Xenopus oocyte maturation. EMBO J, 13, 2131–2138.

Google Scholar - Kumagai A and Dunphy WG (1991) The cdc25 protein controls tyrosine dephosphorylation of the cdc2 protein in a cell‐free system. Cell, 64, 903–914.

Google Scholar - Kumagai A and Dunphy WG (1992) Regulation of the cdc25 protein during the cell cycle in Xenopus extracts. Cell, 70, 139–151.

Google Scholar - Kumagai A and Dunphy WG (1996) Purification and molecular cloning of Plx1, a Cdc25‐regulatory kinase from Xenopus egg extracts. Science, 273, 1377–1380.

Google Scholar - Kumagai A and Dunphy WG (1997) Regulation of Xenopus Cdc25 protein. Methods Enzymol, 283, 564–571.

Google Scholar - Leevers SJ and Marshall CJ (1992) Activation of extracellular signal‐regulated kinase, ERK2, by p21ras oncoprotein. EMBO J, 11, 569–574.

Google Scholar - Leighton IA, Dalby KN, Caudwell FB, Cohen PTW and Cohen P (1995) Comparison of the specificities of p70 S6 kinase and MAPKAP kinase‐1 identifies a relatively specific substrate for p70 S6 kinase: the N‐terminal kinase domain of MAPKAP kinase‐1 is essential for peptide phosphorylation. FEBS Lett, 375, 289–293.

Google Scholar - Lew DJ and Kornbluth S (1996) Regulatory roles of cyclin dependent kinase phosphorylation in the cell cycle control. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 8, 795–804.

Google Scholar - Liu F, Stanton JJ, Wu Z and Piwnica‐Worms H (1997) The human Myt1 kinase preferentially phosphorylates cdc2 on threonine 14 and localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi complex. Mol Cell Biol, 17, 571–583.

Google Scholar - Masui Y and Clarke HJ (1979) Oocyte maturation. Int Rev Cytol, 57, 185–282.

Google Scholar - Masui Y and Markert CL (1971) Cytoplasmic control of nuclear behavior during meiotic maturation of frog oocytes. J Exp Zool, 177, 129–145.

Google Scholar - McGowan CH and Russell P (1993) Human wee1 kinase inhibits cell division by phosphorylating p34cdc2 exclusively on Tyr15. EMBO J, 12, 75–85.

Google Scholar - McGowan CH and Russell P (1995) Cell cycle regulation of human wee1. EMBO J, 14, 2166–2175.

Google Scholar - Morgan DO (1995) Principles of CDK regulation. Nature, 374, 131–134.

Google Scholar - Mueller PR, Coleman TR and Dunphy WG (1995a) Cell cycle regulation of a Xenopus Wee1‐like kinase. Mol Biol Cell, 6, 119–134.

Google Scholar - Mueller PR, Coleman TR, Kumagai A and Dunphy WG (1995b) Myt1: a membrane‐associated inhibitory kinase that phosphorylates Ccd2 on both threonine‐14 and tyrosine‐15. Science, 270, 86–90.

Google Scholar - Murakami MS and Vande Woude GF (1998) Analysis of the early embryonic cell cycles of Xenopus; regulation of cell cycle length by Xe‐wee1 and mos. Development, 125, 237–248.

Google Scholar - Murray AW (1991) Cell cycle extracts. Methods Cell Biol, 36, 581–605.

Google Scholar - Nebreda AR and Hunt T (1993) The c‐mos protooncogene protein kinase turns on and maintains the activity of MAP kinase but not MPF, in cell‐free extracts of Xenopus oocytes and eggs. EMBO J, 12, 1979–1986.

Google Scholar - Nebreda AR, Porras A and Santos E (1993a) p21ras‐induced meiotic maturation of Xenopus oocytes in the absence of protein synthesis: MPF activation is preceded by activation of MAP and S6 kinases. Oncogene, 8, 467–477.

Google Scholar - Nebreda AR, Hill C, Gomez N, Cohen P and Hunt T (1993b) The protein kinase Mos activates MAP kinase kinase in vitro and stimulates the MAP kinase pathway in mammalian somatic cells in vivo. FEBS Lett, 333, 183–187.

Google Scholar - Nebreda AR, Gannon JV and Hunt T (1995) Newly synthesized protein(s) must associate with p34cdc2 to activate MAP kinase and MPF during progesterone‐induced maturation of Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J, 14, 5597–5607.

Google Scholar - Parker LL and Piwnica‐Worms H (1992) Inactivation of the p34cdc2–cyclin B complex by the human WEE1 tyrosine kinase. Science, 257, 1955–1957.

Google Scholar - Peverali FA, Isaksson A, Papavassiliou AG, Plastina P, Staszewski LM, Mlodzik M and Bohmann D (1996) Phosphorylation of Drosophila Jun by the MAP kinase rolled regulates photoreceptor differentiation. EMBO J, 15, 3943–3950.

Google Scholar - Posada J, Yew N, Ahn N, Vande Woude GF and Cooper JA (1993) Mos stimulates MAP kinase in Xenopus oocytes and activates a MAP kinase kinase in vitro. Mol Cell Biol, 13, 2546–2553.

Google Scholar - Sagata N, Oskarsson M, Copeland T, Brumbaugh J and Vande Woude GF (1988) Function of c‐mos proto‐oncogene product in meiotic maturation in Xenopus oocytes. Nature, 335, 519–526.

Google Scholar - Sagata N, Daar I, Oskarsson M, Showalter SD and Vande Woude GF (1989) The product of the mos proto‐oncogene as a candidate ‘initiator’ for oocyte maturation. Science, 245, 643–646.

Google Scholar - Sheets MD, Wu M and Wickens M (1995) Polyadenylation of c‐mos mRNA as a control point in Xenopus meiotic maturation. Nature, 274, 511–516.

Google Scholar - Shibuya EK and Ruderman JV (1993) Mos induces the in vitro activation of mitogen‐activated protein kinases in lysates of frog oocytes and mammalian somatic cells. Mol Biol Cell, 4, 781–790.

Google Scholar - Stokoe D, Campbell DG, Nakielny S, Hidaka H, Leevers SJ, Marshall C and Cohen P (1992) MAPKAP kinase‐2; a novel protein kinase activated by mitogen‐activated protein kinase. EMBO J, 11, 3985–3994.

Google Scholar - Strausfeld U, Labbé JC, Fesquet D, Cavadore JC, Picard A, Sadhu K, Russell P and Dorée M (1991) Dephosphorylation and activation of a p34_cdc2_/cyclin B complex in vitro by human CDC25 protein. Nature, 351, 242–245.

Google Scholar - Sturgill TW, Ray LB, Erikson E and Maller JL (1988) Insulin‐stimulated MAP‐2 kinase phosphorylates and activates ribosomal protein S6 kinase II. Nature, 334, 715–718.

Google Scholar - Tang Z, Coleman TR and Dunphy WG (1993) Two distinct mechanisms for negative regulation of the Wee1 protein kinase. EMBO J, 12, 3427–3436.

Google Scholar - Zhao Y, Bjørbœk C and Moller DE (1996) Regulation and interaction of pp90rsk isoforms with mitogen‐activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem, 271, 29773–29779.

Google Scholar