PICK1 is required for the control of synaptic transmission by the metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 (original) (raw)

Introduction

Communication between neurons is initiated by the release of transmitter from the axon terminal into the synaptic cleft. This release process is modulated by various complex mechanisms in the presynaptic terminal. One of these involves autoreceptors located on the axon terminal that are activated by the released transmitter. The autoreceptors can be either ionotropic or metabotropic in nature (Miller, 1998; Frerking and Nicoll, 2000). The presynaptic metabotropic receptors can inhibit neurotransmitter release by affecting Ca2+ as well as K+ channels (Saugstad et al., 1996; Takahashi et al., 1996; Zhang and Schmidt, 1999; Barral et al., 2000; Endo and Yawo, 2000; Robbe et al., 2001), or by acting directly on the protein complex involved in exocytosis of the transmitter (Scanziani et al., 1995). Although these presynaptic mechanisms have been studied extensively, the molecular determinants that couple autoreceptors to their targets have not been identified. At the postsynaptic sites, protein–protein interactions between a number of postsynaptic density‐95 disc‐large zona occludens 1 (PDZ) domain‐containing proteins and the C‐terminus of transmembrane receptors recently were proposed to be important not only in the clustering of these receptors, but also in their coupling to postsynaptic signaling cascades (Scannevin and Huganir, 2000). Similar protein–protein interactions at the presynaptic active zone may participate in the control of transmitter release (Butz et al., 1998; Garner et al., 2000; Gerber et al., 2001). However, whether proteins known to interact with presynaptic receptors are important for the control of synaptic transmission has not been established.

The glutamatergic synapse provides an ideal system to study this issue. This synapse represents the major type of excitatory input in the mammalian central nervous system. Excitatory postsynaptic glutamatergic currents result essentially from the opening of α‐amino‐3‐hydroxy‐5‐methyl‐4‐sioxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor channels. The synaptic release of glutamate is controlled by various presynaptic receptors (Miller, 1998), including metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors (Pin and Duvoisin, 1995). Eight genes have been identified to encode mGlu receptors and classified into three groups. Group I mGlu receptors (mGlu1 and mGlu5 subtypes) are often restricted to the postsynaptic membranes (Lujan et al., 1997), although exceptions have been noted (Cochilla and Alford, 1998). Group II (mGlu2 and mGlu3 subtypes) and group III (mGlu4, mGlu6, mGlu7 and mGlu8 subtypes) mGlu receptors are generally presynaptic (Shigemoto et al., 1997). The mGlu7 receptor subtype is the most representative of these presynaptic mGlu receptors, since it is mainly localized within the presynaptic active zone (Shigemoto et al., 1997). This has led to the hypothesis that mGlu7 receptors reduce synaptic glutamate release through a negative feedback mechanism (Lafon‐Cazal et al., 1999; Dev et al., 2001), which, however, remains to be identified.

The mGlu7a receptor splice variant interacts with the PDZ domain‐containing protein, PICK1 (Boudin et al., 2000; Dev et al., 2000; El Far et al., 2000). This protein scaffolds the receptor into a signaling complex comprising protein kinase Cα (PKCα) (Staudinger et al., 1997; Dev et al., 2000, 2001). The aim of the present study was to identify the role of PICK1 in the mGlu7a receptor‐mediated control of synaptic transmission. Cultured cerebellar granule cells appeared particularly well suited for such an analysis because these neurons have been shown to express endogenous mGlu7 receptors at synaptic sites, and the transduction cascade of the mGlu7a receptor in these cells has been well characterized. It involves inhibition of P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels through a PKC‐dependent phosphorylation cascade (Perroy et al., 2000). Also, the P/Q‐type Ca2+ channel has been shown to trigger a major fraction of cerebellar granule cell mediated‐synaptic transmission (Mintz et al., 1995; Doroshenko et al., 1997). Here we report that interaction of the mGlu7a receptor with PICK1 at presynaptic sites is absolutely required for inhibition of P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels and synaptic activity by this receptor.

Results

Selective inhibition of P/Q‐type Ca 2+ channels by recombinant mGlu7a receptor

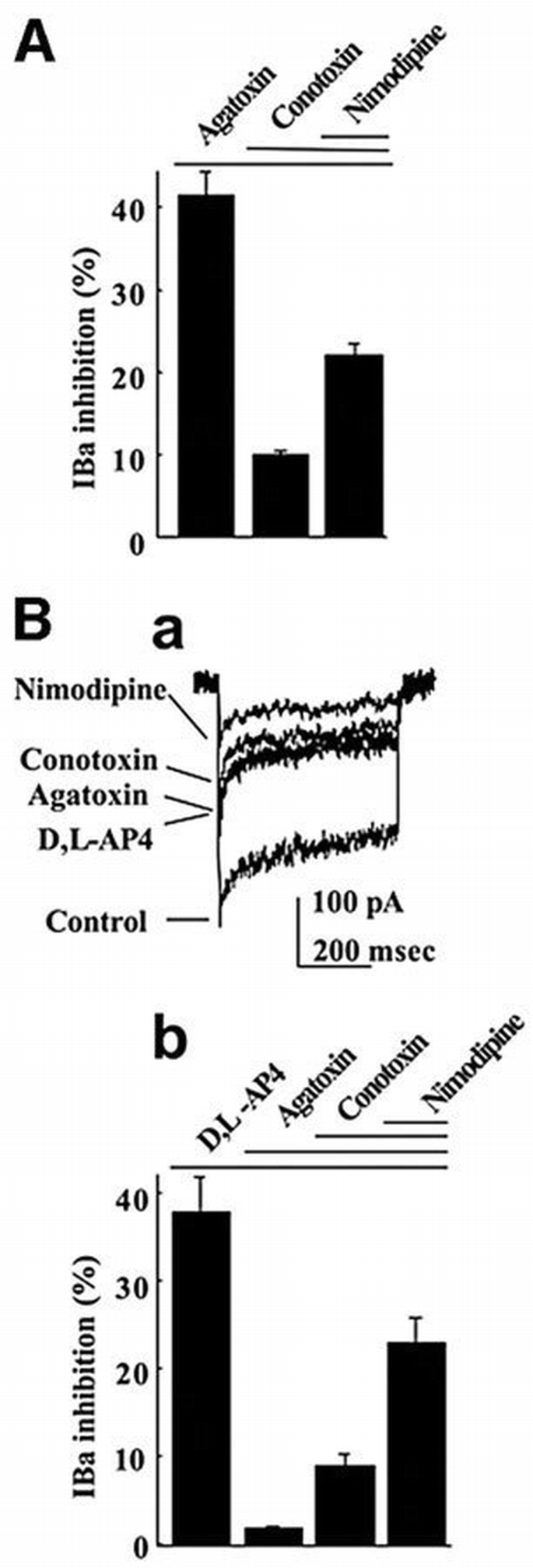

Because of the lack of a selective agonist, the mGlu7a receptor was activated by the group III mGlu receptor agonist, D,L‐2‐amino‐4‐phosphonobutyrate (D,L‐AP4 500 μM + 1 μM MK801; see Materials and methods). This agonist could also activate the other major presynaptic group III mGlu receptor, the mGlu4 subtype (Shigemoto et al., 1997). We eliminated this cross‐talk by performing our experiments in cultured cerebellar granule cells prepared from _mGlu4_‐deficient mice (Pekhletski et al., 1996). We verified that these mGlu4 knock‐out neurons displayed fractions of Ba2+ current (IBa) subtype similar to the wild‐type cultured cerebellar granule cells (Perroy et al., 2000), i.e. 41% of P/Q‐type (sensitive to 250 nM ω‐agatoxin‐IVA), 10% of N‐type (sensitive to 1 μM ω‐conotoxin‐GVIA) and 22% of L‐type (sensitive to 1 μM nimodipine) currents, with the remaining 27% (insensitive) of current being of the R‐type. D,L‐AP4 did not alter total IBa, indicating the absence of functional group III mGlu receptor in the soma of these cells. Transfection of cDNA encoding the mGlu7a receptor (N‐myc‐tagged) into these neurons resulted in both somatic and neuritic expression of the receptor (Figure 2B1; Perroy et al., 2000). This did not alter the relative ratio of IBa subtypes (Figure 1A), nor the selective inhibition of the ω‐agatoxin‐IVA‐sensitive IBa by D,L‐AP4 (Figure 1B). These results showed that the recombinant mGlu7a receptor selectively inhibited P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels in _mGlu4_‐deficient cerebellar granule cells, as reported for wild‐type cerebellar granule cells (Perroy et al., 2000).

Figure 1

Selective inhibition of P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels by the mGlu7a receptor. (A) Inhibitory effects of the indicated drug (nimodipine 1 μM) and toxins (1 μM ω‐conotoxin‐GVIA and 250 nM ω‐agatoxin‐IVA) on IBa. (B) Inhibitory effect of the same drug and toxins, but in the presence of D,L‐AP4 (500 μM), on IBa. Both histograms (A and Bb) and IBa traces (Ba) were obtained from neurons transfected with the mGlu7a receptor. Each bar of the histogram represents the mean (± SEM) of at least 10 experiments.

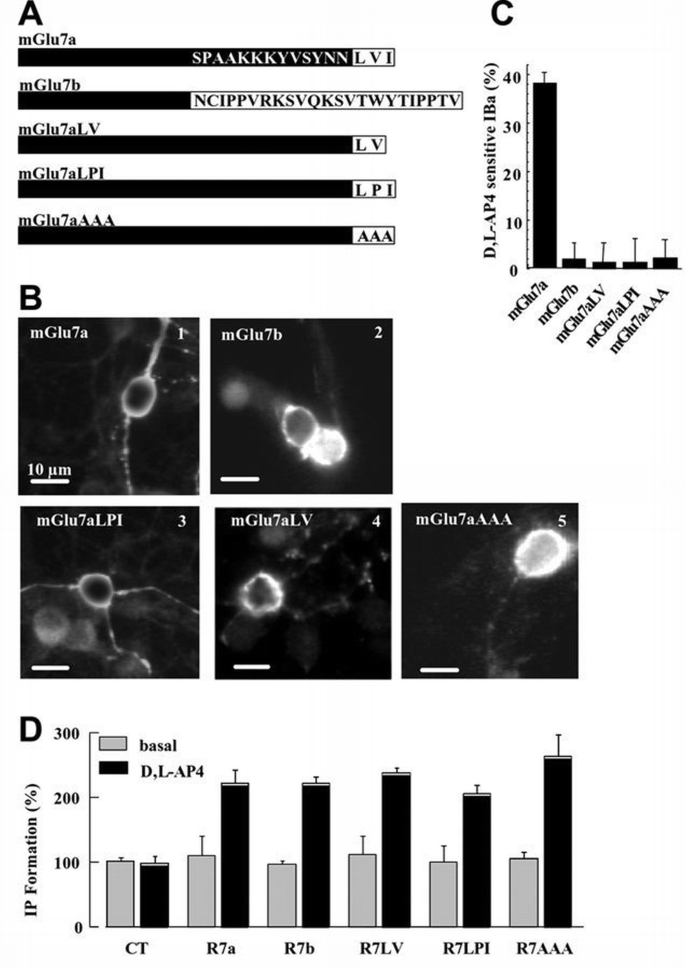

Figure 2

The extreme C‐terminus of the mGlu7a receptor plays an essential role in the coupling between the receptor and Ca2+ channels. (A) C‐terminal sequence of the mGlu7a, mGlu7b and mutated mGlu7a receptor splice variants. (B) Cell surface immunolabeling of the N‐myc‐tagged mGlu7a (1), mGlu7b (2) and mGlu7a mutants receptors (3–5), in living (non‐permeabilized) transfected neurons. In (2), (4) and (5), neuritic immunolabeling of the transfected receptors became apparent when the focus was readjusted on the neurites (not shown). (C) Percentage of IBa inhibition induced by D,L‐AP4, in mGlu7a, mGlu7b or mGlu7a mutant receptor‐transfected neurons. For each bar of the histogram, n ≥7. (D) IP accumulation measured in HEK‐293 cells transiently expressing the indicated receptor and incubated or not (basal) in the presence of D,L‐AP4. The data are expressed as the percentage of basal IP formation obtained in the absence of drug (basal). Values indicated as controls (CT) were obtained in HEK‐293 cells transfected with the empty vector (pRK5). Each bar of the histogram represents the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments performed in triplicate.

PICK1 is required for the mGlu7a receptor‐mediated inhibition of Ca 2+ channels

We then searched for a role for PICK1 in the selective inhibition of P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels by the mGlu7a receptor. The natural mGlu7b receptor splice variant is generated by an out‐of‐frame insertion in the C‐terminus that results in the replacement of the last 16 amino acids of the mGlu7a receptor by 23 different amino acids (Flor et al., 1997; Corti et al., 1998). In the yeast two‐hybrid system, this receptor interacts with much lower affinity than mGlu7a receptor to PICK1 (El Far et al., 2000), and this interaction has not been confirmed in neurons (Boudin et al., 2000; Dev et al., 2000). When transfected in cerebellar granule cells, like the mGlu7a receptor (Figure 2B1), the mGlu7b receptor (tagged at its extracellular N‐terminus with a myc epitope) was expressed at the surface of the soma of these cells, as revealed by immunocytochemistry performed in living (non‐permeabilized) cerebellar granule neurons (Figure 2B2). However, in contrast to the mGlu7a receptor, activation of the mGlu7b receptor with D,L‐AP4 did not affect somatic IBa in these neurons (Figure 2C). Therefore, the extreme C‐terminus of the mGlu7a receptor is required for its selective coupling to P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels.

The C‐terminal LVI sequence of the mGlu7a receptor is essential for its interaction with the PDZ domain of PICK1 (Dev et al., 2000; El Far et al., 2000). We therefore examined its role in the inhibition of Ca2+ channels by this receptor. The LVI sequence was mutated into AAA or LPI, or deleted of its isoleucine residue at position −1 (Figure 2A). Neither the mGlu7aAAA (El Far et al., 2000), nor the mGlu7aLPI or mGlu7aLV (Dev et al., 2000) receptor mutants interact with PICK1. All these mGlu7a receptor mutants (bearing an N‐terminal tag) were expressed at the surface of the cell body of transfected cerebellar granule neurons (Figure 2B3–5). Furthermore, in human embryonic kidney (HEK)‐293‐transfected cells, the inositol (1,4,5)‐trisphosphate (IP3) formation induced by the mutant receptors was similar to that obtained with the mGlu7a receptor, indicating adequate coupling of the mutant receptors to G0‐protein (Figure 2D). However, these mutants failed to inhibit IBa in transfected cultured cerebellar granule cells (Figure 2C). We conclude from these results that the last three C‐terminal amino acids of the mGlu7a receptor are required for coupling the receptor to Ca2+ channels. In agreement with this conclusion, the replacement of the C‐terminal intracellular tail of the mGlu7a receptor by that of the mGlu2 receptor did not affect membrane expression of the chimeric receptor in the soma, but prevented it from inhibiting P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels (2 ± 2% inhibition, n = 6; Perroy et al., 2001).

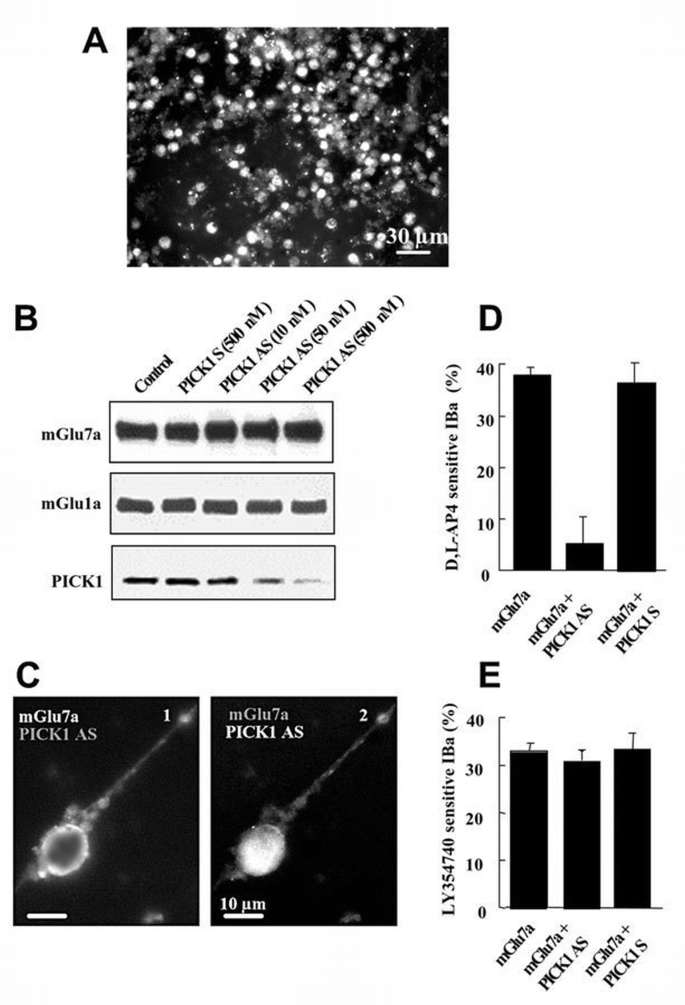

The above results suggested that binding of the wild‐type mGlu7a receptor to PICK1 was required for the coupling of the receptor to Ca2+ channels. This hypothesis was therefore examined in cultured cerebellar granule cells co‐transfected with a fluorescent PICK1 antisense oligonucleotide and a mGlu7a receptor expression plasmid (Figure 3A and C2). Treatment with the antisense, but not sense oligonucleotide abolished expression of PICK1, in a dose‐dependent manner (Figure 3B), without altering the total (Figure 3B) and cell surface (Figure 3C1) expression of transfected mGlu7a receptor, nor total expression of the native mGlu1a receptors (Figure 3B). The relative amounts of the different IBa subtypes were not altered by the antisense oligonucleotide (ω‐agatoxin‐IVA, ω‐conotoxin‐GVIA and nimodipine inhibited 39 ± 2, 10 ± 1 and 23 ± 2% of total IBa, respectively; n = 8). In neurons transfected with mGluR7a and treated with the antisense, but not the sense oligonucleotide, D,L‐AP4 did not significantly affect IBa (Figure 3D). However, activation of PKC by phorbol 12,13‐dibutyrate (PDBu; 1 μM) blocked 29 ± 3% (n = 7) of total IBa in these cells, as in non‐transfected cells (27 ± 5% inhibition of total IBa, n = 7). Subsequent application of ω‐agatoxin‐IVA induced only 4 ± 3% IBa inhibition. This indicated that the PKC‐sensitive IBa was at least of the P/Q type. After 5 days in the absence of antisense oligonucleotide treatment, D,L‐AP4 again blocked 38 ± 5% (n = 8) of IBa. These results also showed that the interaction between mGlu7a receptor and PICK1 was required for the inhibition of P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels by this receptor complex, without affecting the mGlu7a receptor signaling pathway downstream of PKC. In the same neurons, the PICK1 antisense oligonucleotide did not modify the inhibitory effect of native mGlu2 receptor on N‐ and L‐type Ca2+ channels (Figure 3E; Chavis et al., 1995), indicating that the treatment with the antisense oligonucleotide did not alter other activated G0‐protein‐dependent transduction pathways.

Figure 3

PICK1 was required for the mGlu7a receptor‐mediated inhibition of Ca2+ channels. (A) PICK1 fluorescent signal from antisense oligonuclotide transfected in cerebellar granule cells. Note the large number of cells (90%) transfected with the oligonucleotide. A similar result was obtained with a PICK1 sense oligonucleotide. (B) Immunoblots prepared from cultured cerebellar granule cells transfected with mGlu7a receptor alone (Control), or co‐transfected with mGlu7a receptor and PICK1 sense (PICK1 S) or antisense (PICK1 AS) oligonucleotides at the indicated concentration, and revealed using an anti‐mGlu7a receptor, an anti‐mGlu1a receptor or anti‐PICK1 antibodies. (C) Cell surface immunolabeling of the transfected N‐myc‐tagged mGlu7a receptor (1) and intrinsic fluorescence of the transfected PICK1 antisense oligonucleotide (2) in the same living (non‐permeabilized) cell. (D and E) Inhibition of IBa induced by D,L‐AP4 (D) and the mGlu2 receptor agonist, LY354740, (1 μM; E), in neurons transfected with mGlu7a receptor or co‐transfected with mGlu7a receptor and PICK1 antisense (PCIK1 AS) or sense (PICK1 S) oligonucleotides. Each bar of the histograms represents the mean (± SEM) of at least six experiments.

D , L ‐AP4 inhibits spontaneous synaptic activity via blockade of P/Q‐type Ca 2+ channels

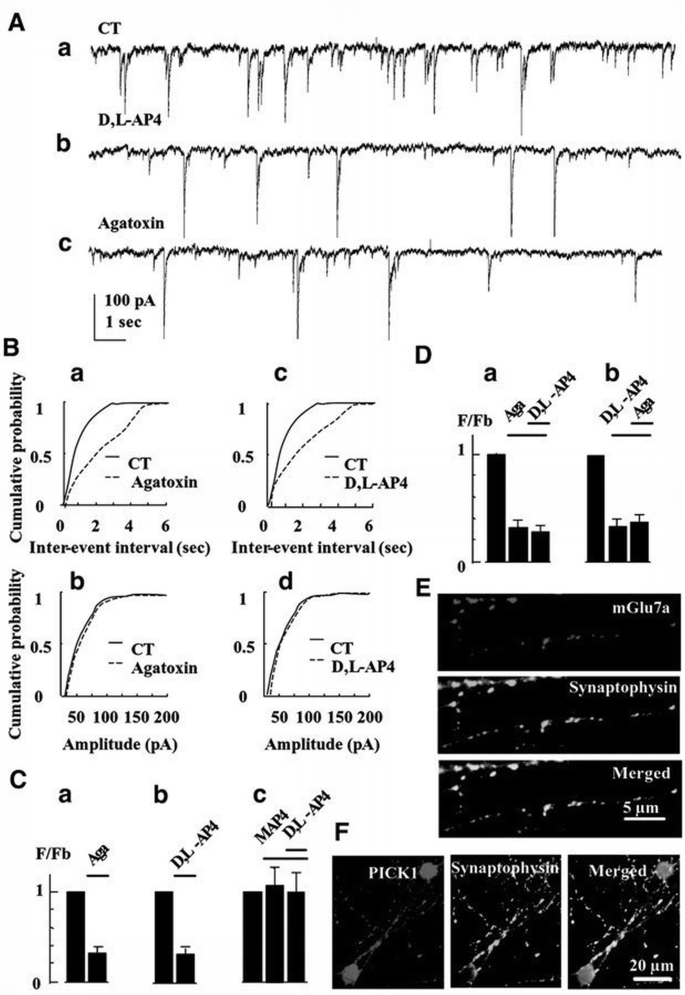

We next examined the possibility that blockade of P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels by endogenous mGlu7a receptor was responsible for inhibition of glutamatergic synaptic transmission. Spontaneous currents were recorded using the whole‐cell patch‐clamp configuration, in non‐ transfected cultured cerebellar granule cells. These currents occurred at a mean basal frequency (_F_b) of 1.1 ± 0.2 Hz (n = 10; Figure 4Aa) and were blocked reversibly by tetrodotoxin (TTX, 0.3 μM; _F_TTX/_F_b = 0.06 ± 0.01, n = 5) or 6‐cyano‐7‐nitroquinoxaline‐2,3‐dione (CNQX, 50 μM; _F_CNQX/_F_b = 0.10 ± 0.02, n = 7). Together, these results indicated that the recorded spontaneous currents were of synaptic glutamatergic (AMPA receptor‐mediated) origin, even if we cannot exclude a presynaptic role for AMPA receptors. ω‐agatoxin‐IVA decreased their spontaneous frequency (Figure 4Ac, Ba and Ca), without affecting their amplitude (Figure 4Bb), indicating that presynaptic P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels controlled transmission at these synapses.

Figure 4

Activation of endogenous mGlu7 receptor with D,L‐AP4 blocks spontaneous synaptic activity. (A) Spontaneous synaptic currents recorded under control condition (CT), or in the presence of D,L‐AP4 or ω‐agatoxin‐IVA, in a non‐transfected neuron. (B) Representative frequency (a and c) and amplitude (b and d) distributions of spontaneous synaptic events obtained from non‐transfected neurons. (C) Relative frequency histograms. In this and all the following histograms, F/_F_b is the ratio of the instantaneous frequency of spontaneous synaptic currents recorded in the presence of the indicated drug over the instantaneous frequency of the spontaneous synaptic currents recorded under control conditions (in the absence of drug), in the same non‐transfected neuron. (a), (b) and (c) were obtained from the same cells (n ≥5). (D) The same as (C). (a) and (b) were obtained from two different sets of cells (n ≥5). (E and F) Co‐localization of the native mGlu7a receptor (E) or PICK1 (F) with synaptophysin, obtained in permeabilized cultured cerebellar granule cells. The three panels in (E) and (F) were taken from the same field.

D,L‐AP4, at a concentration (100 μM) that activates high affinity group III mGlu receptors only (mGlu6, mGlu4 and mGlu8 receptors; Pin and Duvoisin, 1995), did not affect this spontaneous synaptic activity (_F_D,L‐AP4/_F_b = 1.0 ± 0.1, n = 5). However, a higher concentration (500 μM) of this agonist decreased the frequency (Figure 4Ab, Bc and Cb), but not amplitude (Figure 4Bd) of the spontaneous excitatory currents. The group III mGlu receptor‐preferring antagonist, _S_‐2‐amino‐2‐methyl‐4‐phosphonobutanoic acid (MAP4; 410 μM), inhibited the effect of D,L‐AP4 (Figure 4Cc). Separate controls performed in the current‐clamp mode showed that D,L‐AP4 only slightly depolarized the neurons from −70 ± 1 to −63 ± 2 mV (n = 12), without significantly affecting their input resistance (2.1 ± 0.3 and 1.9 ± 0.4 GΩ, in the absence and presence of D,L‐AP4, respectively; n = 10 for each condition). These data indicated an action of the drug on presynaptic low affinity group III mGlu receptors, i.e. most probably the mGlu7 receptor subtype (Okamoto et al., 1994; Saugstad et al., 1994). The inhibitory action of D,L‐AP4 on synaptic currents was not additive with that of ω‐agatoxin‐IVA (Figure 4D), indicating that the activated mGlu7 receptor inhibited synaptic transmission by blocking P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels. Given that in our cultures the recombinant mGlu7a receptor subtype selectively blocked P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels, these results further suggested that the endogenous receptor activated by D,L‐AP4 was of the mGlu7a subtype. We therefore checked for the presence of native mGlu7a receptor subtype in cultured cerebellar granule cells, using a specific anti‐mGlu7a receptor antibody. These studies revealed a punctate pattern of expression and exclusively neuritic localization of native mGlu7a receptors that co‐localized with the presynaptic marker, anti‐synaptophysin antibody (95% mGlu7a‐immunoreactive spots were synaptophysin immunopositive; n = 100 spots taken from three different cultures; Figure 4E). This was consistent with a synaptic localization of this receptor in our cultures.

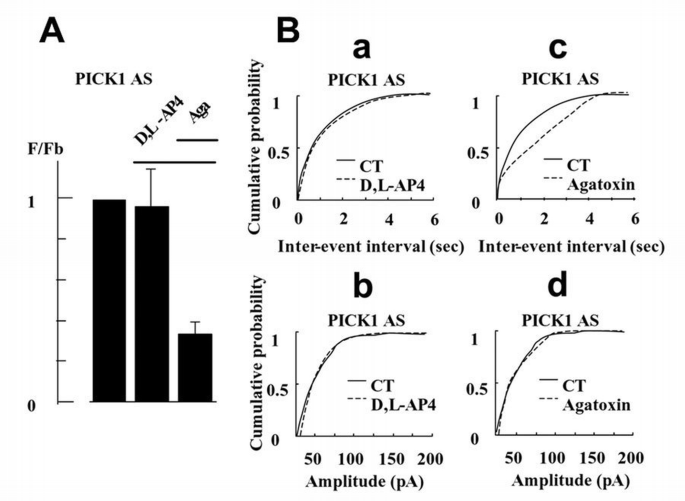

PICK1 is required for inhibition of spontaneous synaptic activity by the mGlu7a receptor

Having established that activation of endogenous presynaptic mGlu7a receptors inhibits spontaneous synaptic activity, we assessed whether PICK1 was involved in this effect. We first checked for the presence of PICK1 in the studied neurons using a specific anti‐PICK1 antibody. We found a homogenous and punctate pattern of expression of this protein in the cell body and neurites that co‐localized with synaptophysin immunoreactivity (95% co‐localization obtained from 100 PICK1‐immunoreactive spots taken from three different cultures; Figure 4F). After treatment of the cultures with a PICK1 antisense (Figure 5), but not sense (not shown) oligonucleotide, application of D,L‐AP4 did not modify the frequency nor amplitude of the spontaneous synaptic events. This indicated that PICK1 was required for the mGlu7a receptor‐mediated inhibition of synaptic transmission. We verified that in the same antisense oligonucleotide‐transfected neurons, ω‐aga toxin‐IVA still decreased the frequency of spontaneous synaptic currents (Figure 5Bc), without affecting their amplitude (Figure 5Bd), indicating that the antisense oligonucleotide did not affect the control of synaptic transmission by the P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels. Similar results were observed after transfection of a PICK1 sense oligonucleotide.

Figure 5

Inhibition of spontaneous synaptic activity mediated by the endogenous mGlu7a receptor required the presence of PICK1. (A) Relative frequency histogram (as in Figure 4C) obtained after PICK1 antisense oligonucleotide treatment, in the presence of D,L‐AP4 and ω‐agatoxin‐IVA (n ≥5 cells). (B) Cumulative probability of inter‐event intervals and amplitude of spontaneous synaptic events (as in Figure 4B) obtained in the presence of D,L‐AP4 (a and b) or ω‐agatoxin‐IVA (c and d), from a neuron treated with a PICK1 antisense oligonucleotide.

PICK1 not only interacts with mGlu7a receptor, but also with AMPA receptor subunits, and clusters these receptors at post‐synaptic sites (Xia et al., 1999; Scannevin and Huganir, 2000). We therefore examined the effect of the PICK1 antisense oligonucleotide on basal spontaneous activity. Neither amplitude nor basal frequency (_F_b = 0.9 ± 0.2 Hz, n = 10) of spontaneous synaptic currents recorded in neurons transfected with the PICK1 antisense oligonucleotide were significantly different from those found in non‐transfected neurons (_F_b = 1.1 ± 0.2 Hz, n = 10). In the same transfected cells, CNQX still inhibited the spontaneous activity (_F_CNQX/_F_b = 0.11 ± 0.30, n = 7). Therefore, knock‐out of PICK1 by the antisense oligonucleotide did not significantly alter the AMPA receptor‐mediated synaptic activity. This observation was in agreement with previous studies showing that under normal conditions, association of PICK1 with AMPA receptors is not essential for synaptic accumulation of these receptors (Osten et al., 2000; Xia et al., 2000). Taken together, these results suggested that presynaptic mGlu7a receptor activation results in a PICK1‐dependent inhibition of P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels and inhibition of synaptic transmission.

Discussion

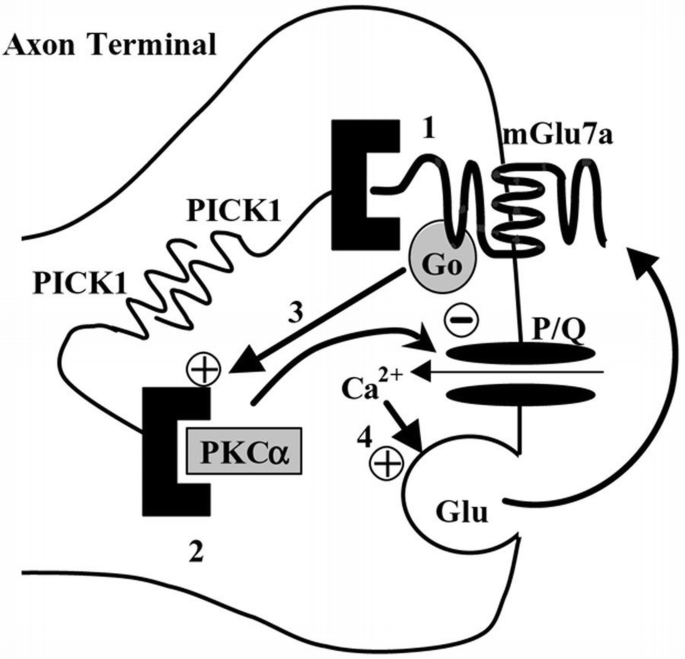

Our results show that the interaction between PICK1 and the C‐terminus of the mGlu7a receptor is required for agonist‐induced inhibition of P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels, as well as for presynaptic control of spontaneous synaptic activity (Figure 6). Taken together, these observations provide the first evidence for a key role of PICK1 in the control of synaptic transmission by the presynaptic mGlu7a receptor.

Figure 6

Model of action of presynaptic mGlu7a receptors on synaptic transmission. The PDZ domain of PICK1 interacts with the C‐terminus of mGlu7a receptors (1) or with the catalytic subunit of PKCα (2). PICK1 dimerizes and thus provides a physical link between the receptor and the kinase. In cerebellar granule cells, these receptors activate a G0‐protein and inhibit P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels through a PKC‐dependent pathway (3) (Perroy et al., 2000). Under enhanced presynaptic activity, the excess of glutamate released would activate this pathway, decrease glutamate transmitter release (4) and reduce synaptic transmission. Our results show that inhibition of both P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels and synaptic transmission requires the presence of PICK1.

The cerebellar cultures as a model to study mGlu7 receptor function

When searching for the presence of endogenous mGlu7a receptor in primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells, we found that this receptor was localized exclusively at neuritic synaptic sites. This was consistent with previous findings showing a predominant localization of mGlu7 receptors at presynaptic sites (Shigemoto et al., 1997). Moreover, we found that both endogenous mGlu7a receptor and PICK1 co‐localized with synaptophysin, suggesting that mGlu7a receptor and PICK1 co‐exist at presynaptic sites. Upon transfection in cerebellar neurons, the recombinant wild‐type receptor was found in both soma and neurites, and this confirmed previous observations in cultured cerebellar granule cells (Perroy et al., 2000) and hippocampal neurons (Stowell and Craig, 1999). The reason for the different localization of the endogenous and recombinant receptors is unknown. It may be argued that this resulted from an insufficient amount of native PICK1 to transport the receptor to the synapse. However, strong PICK1 immunolabeling was found in both soma and neurites in our cultured cerebellar granule cells. Moreover, specific mutation/deletion experiments showed that PICK1 was not required for the neuritic targeting of the receptor, in either cerebellar granule cells (present study) or hippocampal neurons (Boudin et al., 2000; McCarthy et al., 2001). Similarly to the wild‐type mGlu7a receptor, the different mGlu7a receptor constructs used here, as well as the mGlu7b receptor, were incorporated into the neuronal plasma membrane. This was in agreement with other reports showing that interaction with PICK1 is not required for cell surface trafficking of the mGlu7a receptor (Boudin et al., 2000).

Role of PICK1 in the mGlu7a receptor coupling to Ca 2+ channels

Here we provide evidence for a new function for PICK1 in neurons: the support of specific inhibition of P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels by the mGlu7a receptor. In addition to this effect, PICK1 aggregates the mGlu7a receptor at synaptic sites in hippocampal neurons (Boudin et al., 2000) and downregulates the PKC‐mediated phosphorylation of the receptor in COS‐7 cells (Dev et al., 2000). A number of other intracellular proteins have been shown to interact with receptors and cluster them into large complexes, but only a few of them have been found to play a role in the receptor function (Scannevin and Huganir, 2000). For instance, the Na+/H+ exchanger regulator factor (NEHRF) aggregates β2‐adrenergic receptors, and this association controls the activity of the Na+/H+ exchanger (Hall et al., 1998). Also, Homer proteins cluster group I mGlu receptors and control their Ca2+ signaling in neurons (Tu et al., 1998). Homer also controls group I mGlu receptor coupling to Ca2+ and K+ channels in neurons (Kammermeier et al., 2000). This function of Homer was reminiscent of the role of PICK1 in the mGlu7a receptor coupling to Ca2+ channels shown here. Thus, a general feature of mGlu receptor‐interacting proteins could be to provide an additional level of coupling specificity between the different receptor subtypes and their effectors that act in addition to the G‐protein selectivity.

The mechanism by which PICK1 promoted the coupling between the mGlu7a receptor and the Ca2+ channel is not understood. PICK1 could dimerize and scaffold the mGlu7a receptor with PKCα to form an mGlu7a receptor–PICK1–PKCα signaling complex (Staudinger et al., 1997; Xia et al., 1999; Dev et al., 2000; El Far et al., 2000). However, this complex has not been described to interact directly with any ion channel. Therefore, an additional factor might be required for coupling the mGlu7a receptor to P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels. This factor could be another scaffolding protein that would physically link the mGlu7a receptor complex to the channel. The A‐kinase anchoring protein 79/150 (AKAP79/150) has been described to interact with PKCα and ionic channels (Carr et al., 1992; Coghlan et al., 1995; Klauck et al., 1996; Fraser and Scott, 1999; Colledge et al., 2000) and therefore is a potential candidate for such a function. Alternatively, PKCα might not interact directly with P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels, but rather phosphorylate specific sites on these membrane proteins. However, in spite of multiple consensus PKC phosphorylation sites on the Cav2.1 subunit, none of them has yet been described to constitute a specific target of a particular PKC subtype.

In addition to PICK1, calmodulin and G‐protein βγ subunits have been shown to interact in a mutually exclusive manner with the C‐terminus of the mGlu7 receptor (Nakajima et al., 1999; O‘Connor et al., 1999). This interaction occurs in the proximal C‐terminus of the receptor, which is common to the mGlu7a and mGlu7b receptor variants and is thought to be important for efficient signaling through G‐protein βγ subunits (O'Connor et al., 1999; El Far et al., 2000). Since only the mGlu7a receptor variant was able to inhibit Ca2+ channels in cerebellar granule cells, it is unlikely that calmodulin contributed directly to the coupling between the mGlu7a receptor and Ca2+ channels in these cells. This did not exclude any other possible calmodulin‐dependent regulation of this signaling pathway, since calmodulin has been shown to promote L‐AP4‐induced inhibition of synaptic transmission in hippocampal preparations (O'Connor et al., 1999).

The mGlu7b receptor has been shown also to interact with PICK1 in the yeast two‐hybrid system, although with much lower affinity than the mGlu7a receptor (El Far et al., 2000). Therefore, although when overexpressed, somatic mGlu7b receptor did not affect Ca2+ currents, we cannot rule out an effect of this receptor on spontaneous synaptic currents.

Role of PICK1 in the mGlu7a receptor‐mediated inhibition of synaptic transmission

Our results support the hypothesis that the mGlu7 receptor, PICK1 and P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels are co‐expressed at presynaptic sites. This hypothesis is also documented by other immunocytochemical and functional studies (Turner et al., 1992; Takahashi and Momiyama, 1993; Regehr and Mintz, 1994; Wheehler et al., 1994; Dunlap et al., 1995; Shigemoto et al., 1996; Kinzie et al., 1997; Torres et al., 1998; Jun et al., 1999; Xia et al., 1999). It is worth noting that only high concentrations of D,L‐AP4 were effective in inhibiting spontaneous synaptic activity. This confirmed the absence of functional, higher affinity mGlu4 (in mGlu4 knock‐out neurons; Pekhletski et al., 1996), mGlu6 (exclusively expressed in the retina; Nomura et al., 1994) and mGlu8 receptor subtypes in cerebellar granule cells.

Our study of spontaneous activity was performed in the absence of TTX, because the mGlu7a receptor was expected to inhibit synaptic transmission through blockade of voltage‐activated Ca2+ channels. The recorded spontaneous events might therefore comprise both action potential‐dependent and ‐independent synaptic events. However, we showed that the mGlu7 receptor agonist, D,L‐AP4: (i) altered the frequency but not the amplitude of spontaneous events; (ii) did not significantly alter membrane potential nor membrane resistance of the neurons; (iii) its inhibitory effect on Ca2+ currents was blocked by the receptor antagonist, MAP4; and (iv) such an effect was not additive to that of agatoxin‐IVA. Altogether, these observations suggested a presynaptic mGlu7 receptor‐mediated inhibition of transmitter release through blockade of P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels, rather than an action of D,L‐AP4 on the presynaptic cell firing or exocytosis machinery, as reported for cannabinoid presynaptic receptors (Robbe et al., 2001).

In conclusion, our results suggest an mGlu7a receptor‐mediated negative feedback control of synaptic transmission that depends on the interaction of the receptor with the scaffolding protein PICK1 and inhibition of P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels. Thus, a function for PICK1, in addition to assembling mGlu7a receptors at presynaptic active zones, is to allow the receptor coupling to specific targets that control neurotransmitter release.

The mGlu7 receptor displays low affinity for glutamate (Okamoto et al., 1994; Saugstad et al., 1994), suggesting that this receptor is activated only when the concentration of glutamate in the synaptic cleft is elevated sufficiently. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that group III mGlu receptors, possibly of the mGlu7a subtype, inhibit excitatory synaptic transmission during high‐ but not low‐frequency synaptic activity, in the locus coeruleus (Dube and Marshall, 2000). This demonstrates that the mGlu7a receptor–PICK1 complex is neuroprotective and is consistent with physiological studies showing a marked susceptibility of adult mGlu7 receptor knock‐out mice to epileptic agents (Masugi et al., 1999; Sansig et al., 2001).

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Primary cultures of cerebellar cells were prepared from mGlu4 knock‐out mice (Pekhletski et al., 1996), as previously described (Van Vliet et al., 1989). Briefly, 1‐week‐old newborn mice were decapitated and the cerebellum dissected. The tissue was then triturated gently using fire‐polished Pasteur pipets and the homogenate was centrifuged at 500 r.p.m. The pellet was resuspended and plated in tissue culture dishes previously coated with poly‐L‐ornithine. Cells were maintained in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and F‐12 nutrient (Gibco), supplemented with glucose (30 mM), glutamine (2 mM), sodium bicarbonate (3 mM) and HEPES buffer (5 mM), decomplemented fetal calf serum (10%) and 25 mM KCl in order to improve neuronal survival. One‐week‐old cultures contained 106 cells.

Plasmids, oligonucleotides and transfection

All the studied mGlu7 receptors were tagged at their N‐terminus with either a myc (wild‐type mGlu7a, mGlu7aLPI, mGlu7aLV and wild‐type mGlu7b receptor) or flag (mGlu7aAAA receptor) epitope, as described previously (El Far et al., 2000; Perroy et al., 2000). The antisense oligonucleotide (tgtcatagtctaagtctgcaaacat; Eurogentec, Angers, France) corresponded to positions 1–25 of the mouse PICK1 gene. The antisense and sense oligonucleotides were phosphorothioated and labeled with _S_‐modified [3′]fluorescein before transfection into cultured neurons.

Immediately before plating, cerebellar cultures were co‐transfected with the mGlu7 receptors and the transfection marker, green fluorescent protein (GFP)‐containing plasmid, pEGFP‐N1 (Clontech), using the transfection lipid, Transfast (Ango et al., 1999). The sense or antisense oligonucleotides were transfected using the same method, at a concentration of 0.5 μM. The oligonucleotides were then added at this concentration every 2 days, in the absence of Transfast, until the day of the experiment. Under these conditions, 90% of the neurons were transfected with the oligonucleotides (Figure 3A), which allowed us to study their effects using immunoblots and electrophysiological recordings of spontaneous synaptic events. GFP or oligonucleotide fluorescent signals served to visualize the transfected neurons in electrophysiological studies of IBa.

Immunological analyses

Immunocytochemistry and western blots were performed in 7–10 days in vitro (DIV) cultures using a rabbit anti‐mGlu7a receptor (0.5 μg/ml) and rabbit anti‐PICK1 (1/50 dilution) antibodies, the specificity of which has been described previously (Shigemoto et al., 1996, 1997; El Far et al., 2000). Co‐immunolabeling of synaptophysin was performed using a mouse anti‐synaptophysin antibody (1/200; Calbiochem). For these immunocytochemical experiments, cerebellar cultures were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde/0.1 M glucose‐containing phospate‐buffered saline (PBS) solution, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X‐100 and incubated overnight, at room temperature, in the presence of the anti‐mGlu7a receptor antibody. The presence of myc‐ or flag‐tagged proteins at the cell surface of cultured neurons was examined in living (non‐permeabilized) cells exposed for 30 min at 37°C to a polyclonal rabbit anti‐myc (1/300; ABR Inc., CO) or mouse anti‐flag (1/700; Sigma, France) primary antibody. Cells were then rinsed, fixed as described above and exposed for 2 h at room temperature to the following secondary antibodies: a goat Texas Red‐conjugated anti‐rabbit IgG (1/1000) and a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐conjugated anti‐mouse (1/400) antibody (both from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratory, PA). Cells were then rinsed with PBS and mounted on glass coverslips for observation on an Axiophot 2 Zeiss microscope. Immunoblotings were performed as described previously (Blahos et al., 1998), using the rabbit anti‐mGlu7a receptor (0.5 μg/ml) and rabbit anti‐PICK1 antibodies.

Measurement of inositol phosphate accumulation

The wild‐type and mutant receptors were tested for their coupling to G‐protein in HEK‐293 cells, using the method that we described previously (Parmentier et al., 1998). Briefly, inositol phosphate (IP) accumulation was measured in HEK‐293 cells co‐transfected with the tested receptor and a recombinant G‐protein. The receptors were co‐transfected with a chimeric Gqi9‐protein. In the Gqi9 chimeric protein, the C‐terminal nine residues of the G‐protein αq subunit were replaced by those of the G‐protein αi2 subunit, enabling the coupling of the receptors to phospholipase C (Parmentier et al., 1998).

Electrophysiology

We used the whole‐cell patch‐clamp configuration to record IBa from GFP‐expressing (mGlu receptor co‐transfected) cerebellar granule cells, after 9 ± 1 DIV, as described previously (Ango et al., 1999). The bathing medium contained: 20 mM BaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM tetraethylammonium acetate, 3 × 10−4 mM TTX, 10 mM glucose, 120 mM Na‐acetate and 10−3 mM MK‐801, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH and 330 mOsm with Na‐acetate. Drug solutions were prepared in this medium and pH readjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. Group III mGlu receptors were activated using D,L‐AP4. The _N_‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor channel blocker, MK‐801 (1 μM), was added to all solutions in order to avoid activation of this receptor by the D‐isoform of D,L‐AP4 (unpublished observation). Patch pipets were made from borosilicate glass, coated with Sylgard, and their tip fire‐polished. Pipets had resistances of 3–5 MΩ when filled with the following internal solution: 100 mM Cs‐acetate, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 15 mM glucose, 20 mM CsCl, 20 mM EGTA, 2 mM Na2ATP and 1 mM cAMP, adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH and 300 mOsm with Cs‐acetate.

Barium currents were evoked by 500 ms voltage‐clamp pulses, from a holding potential of −80 mV, to a test potential of 0 mV, applied at a rate of 0.1 Hz. Current signals were recorded using an Axopatch 200 amplifier, filtered at 1 kHz with an 8‐pole Bessel filter and sampled at 3 kHz on a Pentium II PC computer. Analyses were performed using the pClamp6 program of Axon Instruments. Barium currents were measured at their peak amplitude and values expressed as mean ± SEM of the indicated number (n) of experiments. A 20 mV voltage step from a holding potential of −80 mV elicited a monoexponential transient current. Input resistance was computed from the steady current flowing after termination of such transient.

Spontaneous currents were recorded in a bathing medium composed of 140 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 3 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM D‐glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH and 330 mOsm with NaCl. Whole‐cell patch clamp electrodes contained 140 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM D‐glucose, adjusted to pH 7.2 with KOH and 300 mOsm with KCl. The spontaneous activity was recorded in neurons held at a potential of −80 mV and analyzed offline using the Axograph 4.5 software from Axon Instruments. The software detected events on the basis of amplitudes exceeding a threshold of −25 pA below baseline noise of the recording. All the detected events were re‐examined and accepted or rejected on the basis of visual examination. The program then measured amplitudes and intervals between successive detected events. The frequency of spontaneous activity was calculated by dividing the total number of detected events (100 ± 10 events) by the total time sampled. Cumulative probability plots were constructed to compare amplitude and inter‐event interval distributions of spontaneous currents obtained from different experimental conditions. Amplitude and inter‐event interval histograms were binned in 1 pA and 20 ms intervals, respectively. Frequencies were also normalized by calculating the F/_F_b ratio, where F and _F_b were frequency values obtained from the same cell during the test and control conditions, respectively. Data obtained from the indicated number (n) of cells were expressed as the mean ± SEM and analyzed using the Student's _t_‐test, with P ≤ 0.05.

Materials

D,L‐AP4, CNQX, MK‐801 and MAP4 were purchased from Tocris Cockson (UK). Nimodipine was purchased from RBI (USA). ω‐agatoxin‐IVA and ω‐conotoxin‐GVIA were from Alomone Labs (Israel), and PDBu from Fluka (France). LY354740 was a generous gift from D.Schoepp (Lilly).

References

- Ango F, Albani‐Torregrossa S, Joly C, Robbe D, Michel JM, Pin JP, Bockaert J and Fagni L (1999) A simple method to transfer plasmid DNA into neuronal primary cultures: functional expression of the mGlu5 receptor in cerebellar granule cells. Neuropharmacology, 38, 793–803.

Google Scholar - Barral J, Toro S, Galarraga E and Bargas J (2000) GABAergic presynaptic inhibition of rat neostriatal afferents is mediated by Q‐type Ca2+ channels. Neurosci Lett, 283, 33–36.

Google Scholar - Blahos J, Mary S, Perroy J, de Colle C, Brabet I, Bockaert J and Pin JP (1998) Extreme C terminus of G protein α‐subunits contains a site that discriminates between Gi‐coupled metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Biol Chem, 273, 25765–25769.

Google Scholar - Boudin H, Doan A, Xia J, Shigemoto R, Huganir RL, Worley P and Craig AM (2000) Presynaptic clustering of mGluR7a requires the PICK1 PDZ domain binding site. Neuron, 28, 485–497.

Google Scholar - Butz S, Okamoto M and Sudhof TC (1998) A tripartite protein complex with the potential to couple synaptic vesicle exocytosis to cell adhesion in brain. Cell, 94, 773–782.

Google Scholar - Carr DW, Stofko‐Hahn RE, Fraser IDC, Cone RD and Scott JD (1992) Localization of the cAMP‐dependent protein kinase to the postsynaptic densities by A‐kinase anchoring proteins: characterization of AKAP79/150. J Biol Chem, 24, 16816–16823.

Google Scholar - Chavis P, Fagni L, Bockaert J and Lansman JB (1995) Modulation of calcium channels by metabotropic glutamate receptors in cerebellar granule cells. Neuropharmacology, 34, 929–937.

Google Scholar - Cochilla AJ and Alford S (1998) Metabotropic glutamate receptor‐mediated control of neurotransmitter release. Neuron, 20, 1007–1016.

Google Scholar - Coghlan VM, Perrino BA, Howard H, Langeberg LK, Hicks JB, Gallatin WM and Scott JD (1995) Association of protein kinase A and protein phosphatase 2B with a common anchoring protein. Science, 267, 108–112.

Google Scholar - Colledge M, Dean RA, Scott GK, Langeberg LK, Huganir RL and Scott JD (2000) Targeting of PKA to glutamate receptors through a MAGUK–AKAP complex. Neuron, 27, 107–119.

Google Scholar - Corti C, Restituito S, Rimland JM, Brabet I, Corsi M, Pin JP and Ferraguti F (1998) Cloning and characterization of alternative mRNA forms for the rat metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR7 and mGluR8. Eur J Neurosci, 10, 3629–3641.

Google Scholar - Dev KK, Nakajima Y, Kitano J, Braithwaite SP, Henley JM and Nakanishi S (2000) PICK1 interacts with and regulates PKC phosphorylation of mGLUR7. J Neurosci, 20, 7252–7257.

Google Scholar - Dev KK, Nakanishi S and Henley JM (2001) Regulation of mglu7 receptors by proteins that interact with the intracellular C‐teminus. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 22, 355–361.

Google Scholar - Doroshenko PA, Woppmann A, Miljanich G and Augustine GJ (1997) Pharmacologically distinct presynaptic calcium channels in cerebellar excitatory and inhibitory synapses. Neuropharmacology, 36, 865–872.

Google Scholar - Dube GR and Marshall KC (2000) Activity‐dependent activation of presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors in locus coeruleus. J Neurophysiol, 83, 1141–1149.

Google Scholar - Dunlap K, Luebke JI and Turner TJ (1995) Exocytotic Ca2+ channels in mammalian central neurons. Trends Neurosci, 18, 89–98.

Google Scholar - El Far O, Airas J, Wischmeyer E, Nehring RB, Karschin A and Betz H (2000) Interaction of the C‐terminal tail region of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 with the protein kinase C substrate PICK1. Eur J Neurosci, 12, 4215–4221.

Google Scholar - Endo K and Yawo H (2000) μ‐Opioid receptor inhibits N‐type Ca2+ channels in the calyx presynaptic terminal of the embryonic chick ciliary ganglion. J Physiol, 524, 769–781.

Google Scholar - Flor PJ, Van Der Putten H, Ruegg D, Lukic S, Leonhardt T, Bence M, Sansig G, Knopfel T and Kuhn R (1997) A novel splice variant of a metabotropic glutamate receptor, human mGluR7b. Neuropharmacology, 36, 153–159.

Google Scholar - Fraser IDC and Scott JD (1999) Modulation of ion channels: a ‘current’ view of AKAPs. Neuron, 23, 423–426.

Google Scholar - Frerking M and Nicoll RA (2000) Synaptic kainate receptors. Curr Opin Neurobiol, 10, 342–351.

Google Scholar - Garner CC, Kindler S and Gundelfinger ED (2000) Molecular determinants of presynaptic active zones. Curr Opin Neurobiol, 10, 321–327.

Google Scholar - Gerber SH, Garcia J, Rizo J and Sudhof TC (2001) An unusual C2‐domain in the active‐zone protein piccolo: implications for Ca2+ regulation of neurotransmitter release. EMBO J, 20, 1605–1619.

Google Scholar - Hall RA et al. (1998) The β2‐adrenergic receptor interacts with the Na+/H+‐exchanger regulatory factor to control Na+/H+ exchange. Nature, 392, 626–630.

Google Scholar - Jun K et al. (1999) Ablation of P/Q‐type Ca2+ channel currents, altered synaptic transmission and progressive ataxia in mice lacking the α1A‐subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 96, 15245–15250.

Google Scholar - Kammermeier PJ, Xiao B, Tu JC, Worley PF and Ikeda SR (2000) Homer proteins regulate coupling of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors to N‐type calcium and M‐type potassium channels. J Neurosci, 20, 7238–7245.

Google Scholar - Kinzie JM, Shinohara MM, van den Pol AN, Westbrook GL and Segerson TP (1997) Immunolocalization of metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 in the rat olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol, 385, 372–384.

Google Scholar - Klauck TM, Faux MC, Labudda K, Langeberg LK, Jaken S and Scott JD (1996) Coordination of three signaling enzymes by AKAP79, a mammalian scaffold protein. Science, 271, 1589–1592.

Google Scholar - Lafon‐Cazal M, Fagni L, Guiraud MJ, Mary S, Lerner‐Natoli M, Pin JP, Shigemoto R and Bockaert J (1999) mGluR7‐like metabo tropic glutamate receptors inhibit NMDA‐mediated excitotoxicity in cultured mouse cerebellar granule neurons. Eur J Neurosci, 11, 663–672.

Google Scholar - Lujan R, Roberts JD, Shigemoto R, Ohishi H and Somogyi P (1997) Differential plasma membrane distribution of metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR1α, mGluR2 mGluR5, relative to neurotransmitter release sites. J Chem Neuroanat, 13, 219–241.

Google Scholar - Masugi M, Yokoi M, Shigemoto R, Muguruma K, Watanabe Y, Sansig G, van der Putten H and Nakanishi S (1999) Metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 7 ablation causes deficit in fear response and conditioned taste aversion. J Neurosci, 19, 955–963.

Google Scholar - McCarthy JB, Lim ST, Elkind NB, Trimmer JS, Duvoisin RM, Roudriguez‐Boulan E and Caplan MJ (2001) The C‐terminal tail of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 7 (mGluR7) is necessary but not sufficient for cell surface delivery and polarized targeting in neurons and epithelia. J Biol Chem, 276, 9133–9140.

Google Scholar - Miller RJ (1998) Presynaptic receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 38, 201–227.

Google Scholar - Mintz IM, Sabatini BL and Regehr WG (1995) Calcium control of transmitter release at a cerebellar synapse. Neuron, 15, 675–688.

Google Scholar - Nakajima Y, Yamamoto T, Nakayama T and Nakanishi S (1999) A relationship between protein kinase C phosphorylation and calmodulin binding to the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 7. J Biol Chem, 274, 27573–27577.

Google Scholar - Nomura A, Shigemoto R, Nakamura Y, Okamoto N, Mizuno N and Nakanishi S (1994) Developmentally regulated postsynaptic localization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor in rat rod bipolar cells. Cell, 77, 361–369.

Google Scholar - O'Connor V, El Far O, Bofill‐Cardona E, Nanoff C, Freissmuth M, Karschin A, Airas JM, Betz H and Boehm S (1999) Calmodulin dependence of presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling. Science, 286, 1180–1184.

Google Scholar - Okamoto N, Hori S, Akazawa C, Hayashi Y, Shigemoto R, Mizuno N and Nakanishi S (1994) Molecular characterization of a new metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR7 coupled to inhibitory cyclic AMP signal transduction. J Biol Chem, 269, 1231–1236.

Google Scholar - Osten P et al. (2000) Mutagenesis reveals a role for ABP/GRIP binding to GluR2 in synaptic surface accumulation of the AMPA receptor. Neuron, 27, 313–325.

Google Scholar - Parmentier ML, Joly C, Restituito S, Bockaert J, Grau Y and Pin JP (1998) The G protein‐coupling profile of metabotropic glutamate receptors, as determined with exogenous G proteins, is independent of their ligand recognition domain. Mol Pharmacol, 53, 778–786.

Google Scholar - Pekhletski R, Gerlai R, Overstreet LS, Huang XP, Agopyan N, Slater NT, Abramow‐Newerly W, Roder JC and Hampson DR (1996) Impaired cerebellar synaptic plasticity and motor performance in mice lacking the mGluR4 subtype of metabotropic glutamate receptor. J Neurosci, 16, 6364–6373.

Google Scholar - Perroy J, Prézeau L, De Waard M, Shigemoto R, Bockaert J and Fagni L (2000) Selective blockade of P/Q‐type calcium channels by the metabotropic glutamate receptor type 7 involves a phospholipase C pathway in neurons. J Neurosci, 20, 7896–7904.

Google Scholar - Perroy J, Gutierrez G, Coulon V, Bockaert J, Pin JP and Fagni L (2001) The carboxylic terminus of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes 2 and 7 specifies the receptor signaling pathways. J Biol Chem, 276, 45800–45805

Google Scholar - Pin JP and Duvoisin R (1995) The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and functions. Neuropharmacology, 34, 1–26.

Google Scholar - Regehr WG and Mintz IM (1994) Participation of multiple calcium channel types in transmission at single climbing fiber to Purkinje cell synapses. Neuron, 12, 605–613.

Google Scholar - Robbe D, Alonso G, Duchamp F, Bockaert J and Manzoni OJ (2001) Localization and mechanisms of action of cannabinoid receptors at the glutamatergic synapses of the mouse nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci, 21, 109–116.

Google Scholar - Sansig G et al. (2001) Increased seizure susceptibility in mice lacking metabotropic glutamate receptor 7. J Neurosci, 21, 8734–8745.

Google Scholar - Saugstad JA, Kinzie JM, Mulvihill ER, Segerson TP and Westbrook GL (1994) Cloning and expression of a new member of the L‐2‐amino‐4‐phosphonobutyric acid‐sensitive class of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Mol Pharmacol, 45, 367–372.

Google Scholar - Saugstad JA, Segerson TP and Westbrook GL (1996) Metabotropic glutamate receptors activate G‐protein‐coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels in Xenopus oocytes. J Neurosci, 16, 5979–5985.

Google Scholar - Scannevin RH and Huganir RL (2000) Postsynaptic organization and regulation of excitatory synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci, 1, 133–141.

Google Scholar - Scanziani M, Gahwiler BH and Thompson SM (1995) Presynaptic inhibition of excitatory synaptic transmission by muscarinic and metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in the hippocampus: are Ca2+ channels involved? Neuropharmacology, 34, 1549–1557.

Google Scholar - Shigemoto R, Kulik A, Roberts JD, Ohishi H, Nusser Z, Kaneko T and Somogyi P (1996) Target‐cell‐specific concentration of a metabotropic glutamate receptor in the presynaptic active zone. Nature, 381, 523–525.

Google Scholar - Shigemoto R et al. (1997) Differential presynaptic localization of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci, 17, 7503–7522.

Google Scholar - Staudinger J, Lu J and Olson EN (1997) Specific interaction of the PDZ domain protein PICK1 with the COOH terminus of protein kinase C‐α. J Biol Chem, 272, 32019–32024.

Google Scholar - Stowell JN and Craig AM (1999) Axon/dendrite targeting of metabotropic glutamate receptors by their cytoplasmic carboxy‐terminal domains. Neuron, 22, 525–536.

Google Scholar - Takahashi T and Momiyama A (1993) Different types of calcium channels mediate central synaptic transmission. Nature, 366, 156–158.

Google Scholar - Takahashi T, Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes‐Davies M and Onodera K (1996) Presynaptic calcium current modulation by a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Science, 274, 594–597.

Google Scholar - Torres R, Firestein BL, Dong H, Staudinger J, Olson EN, Huganir RL, Gale NW and Yancopoulos GD (1998) PDZ proteins bind, cluster and synaptically colocalize with Eph receptors and their ephrin ligands. Neuron, 21, 1453–1463.

Google Scholar - Tu JC, Xiao B, Yuan JP, Lanahan AA, Leoffert K, Li M, Linden DJ and Worley PF (1998) Homer binds a novel proline‐rich motif and links group I metabotropic glutamate receptors with IP3 receptors. Neuron, 21, 717–726.

Google Scholar - Turner TJ, Adams ME and Dunlap K (1992) Calcium channels coupled to glutamate release identified by ω‐Aga‐IVA. Science, 258, 310–313.

Google Scholar - Van Vliet BJ, Sebben M, Dumuis A, Gabrion J, Bockaert J and Pin JP (1989) Endogenous amino acid release from cultured cerebellar neuronal cells: effect of tetanus toxin on glutamate release. J Neurochem, 52, 1229–1239.

Google Scholar - Wheehler DB, Randall A and Tsien RW (1994) Role of N and Q type Ca channels in supporting hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science, 264, 107–111.

Google Scholar - Xia J, Zhang X, Staudinger J and Huganir RL (1999) Clustering of AMPA receptors by the synaptic PDZ‐domain containing protein PICK1. Neuron, 22, 179–187.

Google Scholar - Xia J, Chung HJ, Whiler C, Huganir RL and Linden DJ (2000) Cerebellar long‐term depression requires PKC‐regulated interactions between GluR2/3 and PDZ domain‐containing proteins. Neuron, 28, 499–510.

Google Scholar - Zhang C and Schmidt JT (1999) Adenosine A1 and class II metabotropic glutamate receptors mediate shared presynaptic inhibition of retinotectal transmission. J Neurophysiol, 82, 2947–2955.

Google Scholar