Identification of Giardia lamblia Assemblage E in Humans Points to a New Anthropozoonotic Cycle (original) (raw)

Abstract

Giardia lamblia is a pathogen transmitted by water and food that causes infection worldwide. Giardia genotypes are classified into 8 assemblages (A–H). Assemblages A and B are detected in humans, but they are potentially zoonotic because they infect other mammalian hosts. Giardia in samples from 44 children was genotyped. Conserved fragments of the genes encoding β-giardin and glutamate dehydrogenase were sequenced and their alignment were carried out with sequences deposited in GenBank. As expected for Rio de Janeiro, the majority of samples were related to assemblage A. Surprisingly, assemblage E was detected in 15 samples. Detection of assemblage E in humans suggests a new zoonotic route of Giardia transmission.

Giardia lamblia is a waterborne protozoan that infects the intestinal tract. Transmission occurs through the fecal-oral route, which is favored by substandard sanitation conditions and overcrowding. In developed countries, the estimated global distribution ranges from 2% to 7% of the population, but it can reach up to 30% of the population living in low-income countries [1]. Evidence of zoonotic transmission increases the risk for giardiasis.

Currently, 8 G. lamblia assemblages (A–H) are recognized. Assemblages A and B possess anthropozoonotic profiles because they have been described as infecting humans and other hosts, including dogs and cats. The other assemblages were identified in specific hosts: C and D were found in dogs; E, in grazing or herd animals; F, in cats; G, in rats and mice; and, more recently, H, in seals [1, 2].

As the genotypic characterization studies progress, evidence that a particular assemblage is able to infect hosts not yet described is mounting, which also suggests new transmission routes. In this way, assemblage E was recently described in rabbits, nonhuman primates, and humans [3, 4], while assemblage F was detected in cattle [5]. Herein, we evaluated the distribution of G. lamblia genotypes in children inhabiting an urban slum and suggest an additional route of anthropozoonotic fecal-oral transmission.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and Detection of Intestinal Parasites in Stool

The study was developed in a community of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The slum has a limited drinking water supply and no sewage network coverage, and few streets are paved. Stray animals, such as dogs, cats, rodents, pigs, horses, and cattle are commonly found moving throughout location. The community has a vegetable garden that is fertilized with feces of hooved animals.

All nursery attendees were invited to participate in this study. Samples were obtained from 89 of 95 preschoolers (age range, 10 months to 4 years) and 35 of 36 employees. A collector accompanied by instructions was provided for the guardians of children and nursery volunteers. One stool sample from each participant was examined for intestinal protozoa and helminthes. Biological samples were obtained after informed consent was obtained from each subject or guardians of the children. All the procedures were approved by the ethical committee for human research (Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz).

Molecular Characterization

G. lamblia DNA from cysts was extracted using the QIAmp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany), with modifications (lysis temperature, 95°C; elution buffer, 100 µL). Purified DNA was stored at 4°C until use. Conserved fragments from the genes encoding glutamate dehydrogenase (gdh) and β-giardin (βgia) were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), as described elsewhere [6–8], except for the use of recombinant Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Brazil; Supplementary Table 1). A positive control consisted of DNA from an axenic culture of G. lamblia strain WB ATCC50803, and a negative control consisted of DNA from axenic cultures of Trichomonas vaginalis and Entamoeba histolytica.

The amplicons obtained for each pair of primers were purified using NucleoSpin Gel and a PCR Clean-up kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany), with a minor change in incubation duration (increased to 5 minutes). The purified products were subjected to sequencing in both directions in triplicate, using the ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit on an ABI 3730 automatic DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). The obtained sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KU921280–KU921367.

Electropherograms were analyzed using Chromas 2.4 (Technelysium, South Brisbane, Australia); characterization of the sequences was performed using the nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool, and the contigs were obtained by the CAP3 Sequence Assembly Program. Nucleotide sequences of gdh and βgia were aligned by the Clustal W algorithm from Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) 6.06 [9]. The phylogenetic analysis was performed using MEGA and the range estimation equations used were JIN and NEI (Kimura 2-parameter model). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm, with bootstrap analysis (1000 replicates). The sequences from the new isolates were aligned using reference sequences of G. lamblia from GenBank to genotype A (gdh: KC960643, AY178735, KM190756, EU278608, and JF918456; βgia: EU014384, HM165227, JQ978667, and JQ978668), genotype B (gdh: DQ090539, JF918437, DQ090540, DQ923580, KM190717, and KP899851; βgia: KP026314, HM165226, and KP026313), and genotype E (gdh: KC960649, KC960651, and KC960652; βgia: DQ116616, KC960635, and KC960641). The outgroups used were Giardia psittaci (gdh: AB714978; βgia: AB714977), Giardia muris (βgia: AY258618), and Trichomonas vaginalis (gdh: AF533886).

RESULTS

G. lamblia Frequency Among Children

Parasitological examination was performed in 35 employees and 89 preschoolers in the day-care unit. Fifty-four preschoolers were infected by at least 1 intestinal parasite, and 44 (49.4%) were positive for Giardia species. None of the employees were positive.

Genotypic Characterization of G. lamblia Strains

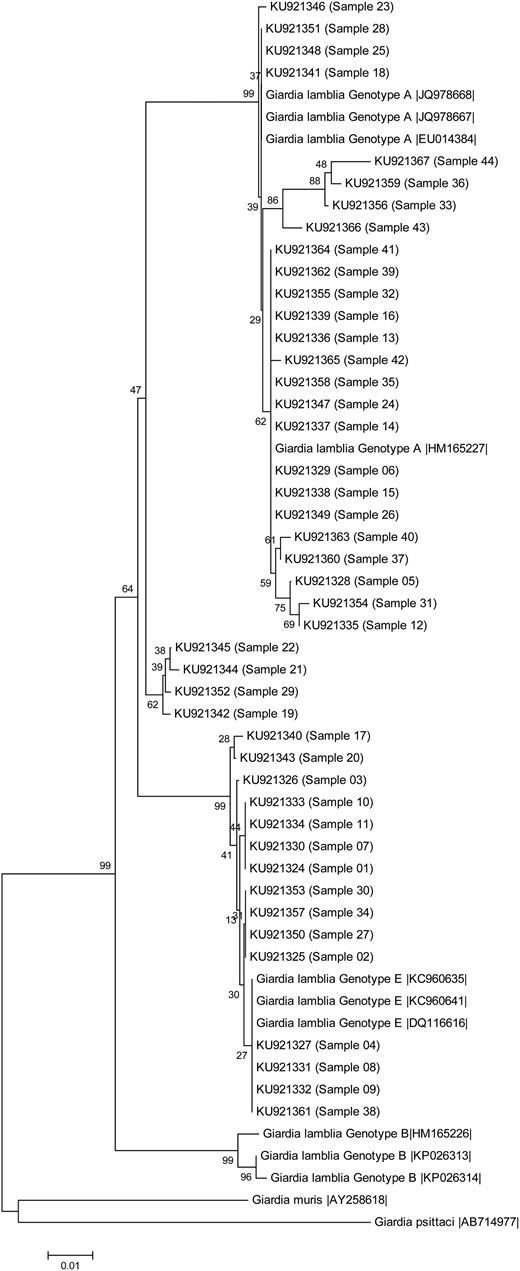

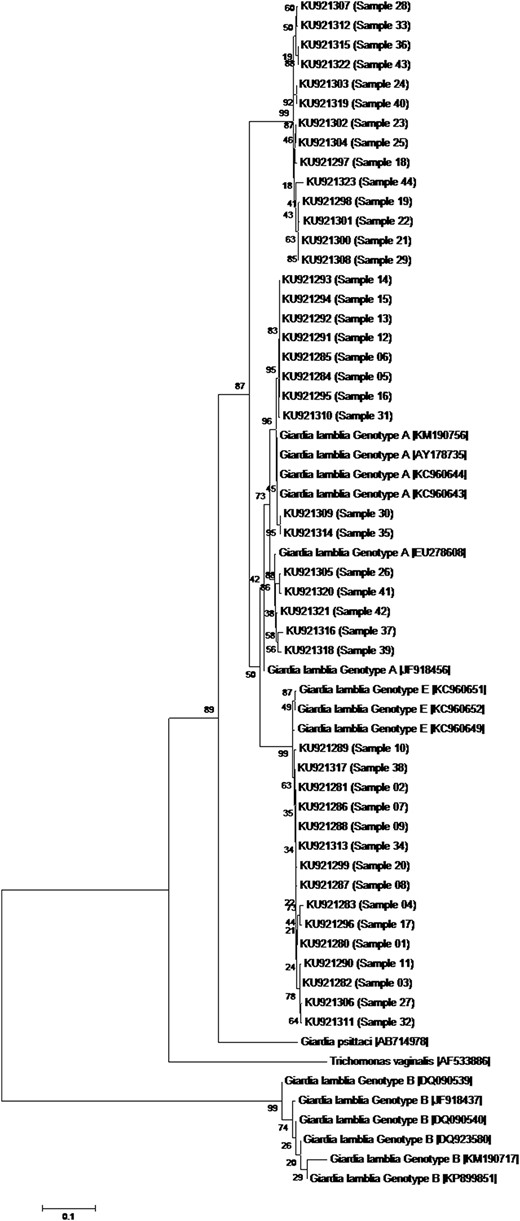

A total of 44 samples positive for G. lamblia had their DNA isolated, and the conserved fragments of βgia and gdh were amplified and sequenced. For both gdh and βgia, 29 sequences were grouped in assemblage A, while 15 sequences were grouped in assemblage E (Figures 1 and 2). In both genes, the samples were grouped similarly, except samples 30 and 32, demonstrating the reproducibility of the arrangement showed by the 2 phylogenetic trees.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the Giardia lamblia isolates collected from children, based on sequences of the gene encoding β-giardin determined by a neighbor-joining algorithm, using a Kimura 2-parameter model. The sample numbers are indicated in parentheses. Sequences obtained from GenBank are indicated by their accession numbers. Values in the tree nodes represent bootstraps. The scale represents the distance in millions of years for the differentiation of each branch.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the Giardia lamblia isolates form children, based on sequences of the gene encoding glutamate dehydrogenase determined by a neighbor-joining algorithm, using a Kimura 2-parameter model. The sample numbers are indicated in parentheses. Sequences obtained from GenBank are indicated by their accession numbers. Values in the tree nodes represent bootstraps. The scale represents the distance in millions of years for the differentiation of each branch.

DISCUSSION

Transmission of G. lamblia is favored by absence of sewage systems and water treatment. Additionally, close contact with stray animals or hoofed animals facilitates the occurrence of anthropozoonotic transmission cycles. These multiples sources increase the risk for G. lamblia infection and can explain the high prevalence of infection observed in the present study. Herein, the systematic genotyping of Giardia strains enabled us to identify assemblage E in human stool.

Previous studies conducted in Rio de Janeiro State demonstrated that genotype A was the most prevalent assemblage identified in humans [10]. As expected, 29 of 44 G. lamblia isolates were clustered as assemblage A by using gdh and βgia conserved genes. Assemblage B was not detected in our study, although it is frequently observed in humans in other regions [11]. Surprisingly, 15 sequences were grouped into assemblage E.

Since the establishment of the assemblage A–G classification, genotype E has been considered livestock specific [1]. Although the gene encoding β-giardin is the gene most indicated to determine assemblage E clustering, the gene encoding glutamate dehydrogenase has also been widely used. Through gene sequencing, assemblage E has been described in stool from cattle, sheep, rodent, and, more recently, from rabbits and nonhuman primates. Despite the tendency toward genetic homogeneity among isolates of the same assemblage, some reports have identified disagreements when all the sequences are compared [6]. G. lamblia has an intrinsic potential to mutate and generate some single-nucleotide polymorphisms, including on chromosome 4 [12]. Moreover, genotypes may vary according to the gene chosen for characterization, as occurred with samples 30 and 32 [6]. More recent descriptions indicate a change in the infective assemblage E profile and even the potential to infect human hosts, which has not been previously described [3, 13–15].

One might question why genotype E was not frequently identified in humans. In previous studies, few clusters were detected, and there was poor reproducibility between the multilocus genes chosen for analysis [4, 6]. It is widely accepted that genotype B is phylogenetically distant from genotypes A and E. However, the real phylogenetic distance between genotypes A and E is unclear. Because the β-giardin gene is considered most indicative of assemblage E clustering, it was chosen for constructing the phylogenetic trees. It is important to stress that G. lamblia assemblage samples were never sequenced in our laboratory, which could discharge contamination due to DNA manipulation. Multilocus analysis amplifying specific targets increases the likelihood of amplifying a mix of genotypes that, in turn, can be confirmed by multilocus strategy.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that humans can be infected by an additional G. lamblia genotype belonging to assemblage E. Any relationship with epidemiology, symptoms, virulence, and pathogenesis of genotype E in humans needs to be investigated. Future genotype grouping studies using a higher number of samples from different species and the identification of other gene targets presenting a better discrimination potential could corroborate our results. It should be stressed that, similar to assemblage A, assemblage E may also present a zoonotic and anthropozoonotic profile.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the Sequencing Service DNA Sequencing Platform–PDTIS/Fundação Oswaldo Cruz and Nivea Oliveira (Laboratório de Parasitologia/FCM-UERJ) for providing parasitological examinations; Elizabeth Salgado and the nursery employees, for their support; and Dr Adeilton Brandão, for helpful discussion and manuscript revision.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz/FIOCRUZ–Brazilian Ministry of Health (internal funds), CAPES (Brasil Sem Miséria/Brazilian governmental program fellowship to M. F.), and CNPq and FAPERJ (research fellowship to A. M. D.-C.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

1

Adam

RD

.

Biology of Giardia lamblia

.

Clin Microbiol Rev

2001

;

14

:

447

–

75

.

2

Lasek-Nesselquist

E

,

Welch

DM

,

Sogin

ML

.

The identification of a new Giardia duodenalis assemblage in marine vertebrates and a preliminary analysis of G. duodenalis population biology in marine systems

.

Int J Parasitol

2010

;

40

:

1063

–

74

.

3

Qi

M

,

Xi

J

,

Li

J

,

Wang

H

,

Ning

C

,

Zhang

L

.

Prevalence of zoonotic Giardia duodenalis assemblage B and first identification of assemblage E in rabbit fecal samples isolates from Central China

.

J Eukaryot Microbiol

2015

;

62

:

810

–

4

.

4

Foronda

P

,

Bargues

MD

,

Abreu-Costa

N

et al. .

Identification of genotypes of Giardia intestinalis of human isolates in Egypt

.

Parasitol Res

2008

;

103

:

1177

–

81

.

5

Cardona

GA

,

de Lucio

A

,

Bailo

B

,

Cano

L

,

de Fuentes

I

,

Carmena

D

.

Unexpected finding of feline-specific Giardia duodenalis assemblage F and Cryptosporidium felis in asymptomatic adult cattle in Northern Spain

.

Vet Parasitol

2015

;

209

:

258

–

63

.

6

Cacciò

SM

,

Beck

R

,

Lalle

M

,

Marinculic

A

,

Pozio

E

.

Multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis reveals striking differences between assemblages A and B

.

Int J Parasitol

2008

;

38

:

1523

–

31

.

7

Cacciò

SM

,

De Giacomo

M

,

Pozio

E

.

Sequence analysis of the beta-giardin gene and development of a polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism assay to genotype Giardia duodenalis cysts from human faecal samples

.

Int J Parasitol

2002

;

32

:

1023

–

30

.

8

Lalle

M

,

Jimenez-Cardosa

E

,

Cacciò

SM

,

Pozio

E

.

Genotyping of Giardia duodenalis from humans and dogs from Mexico using a beta-giardin nested polymerase chain reaction assay

.

J Parasitol

2005

;

91

:

203

–

5

.

9

Tamura

K

,

Dudley

J

,

Nei

M

,

Kumar

S

.

MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0

.

Mol Biol Evol

2007

;

24

:

1596

–

9

.

10

Volotão

AC

,

Costa-Macedo

LM

,

Haddad

FS

,

Brandão

A

,

Peralta

JM

,

Fernandes

O

.

Genotyping of Giardia duodenalis from human and animal samples from Brazil using beta-giardin gene: a phylogenetic analysis

.

Acta Trop

2007

;

102

:

10

–

9

.

11

Oliveira-Arbex

AP

,

David

EB

,

Oliveira-Sequeira

TC

,

Bittencourt

GN

,

Guimarães

S

.

Genotyping of Giardia duodenalis isolates in asymptomatic children attending daycare centre: evidence of high risk for anthroponotic transmission

.

Epidemiol Infect

2016

;

144

:

1418

–

28

.

12

Cooper

MA

,

Adam

RD

,

Worobey

M

,

Sterling

CR

.

Population genetics provides evidence for recombination in Giardia

.

Curr Biol

2007

;

17

:

1984

–

8

.

13

Trout

JM

,

Santín

M

,

Greiner

E

,

Fayer

R

.

Prevalence of Giardia duodenalis genotypes in pre-weaned dairy calves

.

Vet Parasitol

2004

;

124

:

179

–

86

.

14

Thompson

RC

,

Smith

A

,

Lymbery

AJ

,

Averis

S

,

Morris

KD

,

Wayne

AF

.

Giardia in Western Australian wildlife

.

Vet Parasitol

2010

;

170

:

207

–

11

.

15

Du

SZ

,

Zhao

GH

,

Shao

JF

et al. .

Cryptosporidium spp, Giardia intestinalis, and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in captive non-human primates in Qinling Mountains

.

Korean J Parasitol

2015

;

53

:

395

–

402

.

Author notes

Presented in part: XXIVth Congresso da Sociedade Brasileira de Parasitologia - SBP; XXIIIth Congreso Latinoamericano de Parasitología - FLAP, Salvador, Bahia, 27-31 October 2015. Abstract P307.

© The Author 2016. Published by Oxford University Press for the Infectious Diseases Society of America. All rights reserved. For permissions, e-mail [email protected].