Presumptive treatment or serological screening for schistosomiasis in migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa could save both lives and money for the Italian National Health System: results of an economic evaluation (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background

Schistosomiasis can lead to severe irreversible complications and death if left untreated. Italian and European guidelines recommend serological screening for this infection in migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). However, studies on clinical and economic impact of this strategy in the Italian and European settings are lacking. This study aims to compare benefits and costs of different strategies to manage schistosomiasis in migrants from SSA to Italy.

Methods

A decision tree and a Markov model were developed to assess the health and economic impacts of three interventions: (i) passive diagnosis for symptomatic patients (current practice in Italy); (ii) serological screening of all migrants and treating those found positive and (iii) presumptive treatment for all migrants with praziquantel in a single dose. The time horizon of analysis was one year to determine the exact expenses, and 28 years to consider possible sequelae, in the Italian health-care perspective. Data input was derived from available literature; costs were taken from the price list of Careggi University Hospital, Florence, and from National Hospitals Records.

Results

Assuming a population of 100 000 migrants with schistosomiasis prevalence of 21·2%, the presumptive treatment has a greater clinical impact with 86.3% of the affected being cured (75.2% in screening programme and 44.9% in a passive diagnosis strategy). In the first year, the presumptive treatment and the screening strategy compared with passive diagnosis prove cost-effective (299 and 595 cost/QALY, respectively). In the 28-year horizon, the two strategies (screening and presumptive treatment) compared with passive diagnosis become dominant (less expensive with more QALYs) and cost-saving.

Conclusion

The results of the model suggest that presumptive treatment and screening strategies are more favourable than the current passive diagnosis in the public health management of schistosomiasis in SSA migrants, especially in a longer period analysis.

Introduction

Human schistosomiasis is one of the major parasitic diseases of the tropics with more than 229 million people infected in over 78 countries.1,2 Ninety percent of subjects requiring treatment reside in Africa,1 mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where the two main Schistosoma species, Schistosoma mansoni and S. haematobium, are endemic. They are responsible for hepato-intestinal and urogenital schistosomiasis, respectively.3 Schistosomiasis may be present as completely asymptomatic for years but may lead to long-term complications after decades.4,5 Urogenital schistosomiasis in the early phases may cause hematuria and dysuria. However, serious complications such as pseudopolyps of the bladder, infertility and obstructive uropathy possibly leading to end-stage renal failure and bladder cancer may develop in 5–20% of untreated patients.6 Hepato-intestinal schistosomiasis may be present with abdominal discomfort and intermittent diarrhoea, while complications such as liver fibrosis, portal vein hypertension and hematemesis may occur in 4–8% of patients.6

The gold standard for diagnosis is considered to be the parasitological examination of urine (S. haematobium) or faeces (other species); however, these tests have a low sensitivity (45–48%).7 Serological test has a higher sensitivity (up to 90%) and it is considered the most useful screening test.8 Incidentally, the serological tests are not designed to discriminate between active and previous infections; in the setting of migrants screening, a positive serology usually represents an indication to treatment according to most of the guidelines.8–10

The administration of oral drug praziquantel in a single dose regimen is the treatment of choice. Reported treatment efficacy ranges between 73.6 and 76.4% according to the species S. haematobium and S. mansoni, respectively, for a single dose schedule.11 Moreover, after treatment with praziquantel, organ damage, such as bladder pseudopolyps and liver fibrosis, may be totally or partially reverted.12

Schistosomiasis is also a leading travel-related infection affecting both international travellers and migrants.2 Several studies have assessed the prevalence of schistosomiasis in migrants from SSA to Europe with rates ranging between 1 and 60%.13,14 The disease is also a leading cause of hospitalization for migrants from SSA with a rate of 44.63 per 100 000 subjects per year in Italy, where the current practice is passive diagnosis for patients who already have symptoms or are developing them.15

The aim of the study is to evaluate health benefits and economic costs of three alternative public health strategies for the management of schistosomiasis in SSA migrants to Italy in order to provide indications for a new evidence-based protocol which could save both lives and money for the Italian National Health System (NHS).

Material and methods

Study design: decision model and strategies

A mathematical model was developed in Microsoft Excel to compare the following strategies for management of schistosomiasis in migrants from SSA who have recently arrived in Italy:

- (i) Passive diagnosis: migrants from SSA do not receive a screening test or presumptive treatment. Only symptomatic subjects could have diagnostic tests and drug treatment (current practice). This strategy is the comparator in the analysis.

- (ii) Serological screening: migrants are serologically tested for schistosomiasis and will undergo treatment if found positive.

- (iii) Presumptive treatment: all migrants are presumptively treated with praziquantel.

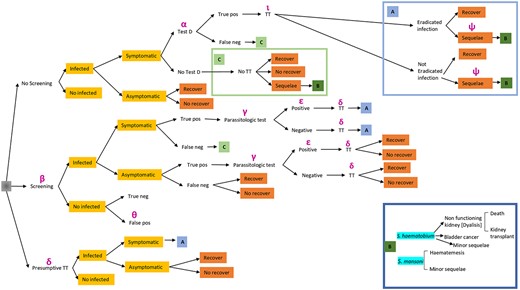

The time horizons for the mathematical model are 1 year and 28 years, considering the assumed average time to develop urogenital schistosomiasis-associated squamous cell carcinoma which is considered to be the latest sequela.16 The decision tree of health status (with related diagnostic tests and treatments) is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The decision tree of health status. Legend: α: cost for passive diagnosis; β: screening tests cost; γ: cost of treatment for symptomatic true positive patients detected by the screening strategy; δ: cost of treatment; ε: cost of patients with true positive screening test and positive; ι: cost of re-assessment in the passive diagnosis strategy; Θ: cost of treatment, clinical visit, parasitological urine test and parasitological test of faeces; ψ: cost of sequelae.

The results are reported as number of cured patients (survived), subjects with sequelae, costs, Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) and Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER). ICER is defined as the difference in costs between two strategies divided by the difference in their effects, with the smaller ICER indicating better cost-effectiveness of one strategy than that of the other.

Data input

Relying on the number of SSA migrants who arrived in Italy from 2014 to 2017 and were registered by United Nation High Commissioner for Refugees, we assumed that a potential population of 100 000 subjects had arrived in a 1-year period with a mean age of 25 years.17 We used data from this time lapse because it represented an unprecedented peak of arrivals in Italy from SSA.

At the initial stage of the model, each subject was supposed to be in a state of being either infected or uninfected by Schistosoma spp. The prevalence of infection was estimated to be 21.2%.14

In the passive diagnosis strategy, the infected subjects can be symptomatic (60%) or asymptomatic (40%).18

It was assumed that only 20% of symptomatic patients would receive a full clinical and laboratory evaluation including an infectious diseases consultation, a specific serological test (Schistosoma spp IgG, Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay, ELISA, sensitivity 76% and specificity 99%7), parasitological tests of urine and faeces, standard urine test, full blood count, creatinine and ALT, while the remaining (80%) would not because of a low level of suspicion by the health practitioners19 or difficulty in accessing the health care system. We decided to use the ELISA test to build the model since our setting comprised a less expensive test with fair performance. Each affected subject (true positive) will undergo a follow-up consultation with an infectious disease specialist, will be screened with an abdominal ultrasound (US) and will undergo treatment with praziquantel in a single dose (40 mg/kg, cure rate 75%11). In case of treatment, the infection could be cured or not, leading to recovery or clinical sequelae due to the persistence of chronic infection because the cure rate is not 100% and irreversible sequelae may have already been established before treatment.11 We considered different types of sequelae depending on the two most common Schistosoma species endemic in SSA (e.g. S. mansoni and S. haematobium).

In the second strategy (screening), all subjects will undergo a serological screening test (IgG ELISA sensitivity 76% and specificity 99%7). Each seropositive subject will undergo infectious disease specialist consultation and parasitological test of urines and faeces with an expected positive rate of 37.9%.20 Subjects with negative parasitological test will receive treatment with praziquantel in a single dose (40 mg/kg), while those with positive parasitological findings will undergo an infectious disease consultation and an abdominal US in addition to treatment with praziquantel.21

In both passive diagnosis and screening strategy, false negative and false positive serological tests are possible. Infected subjects with false negative serology could develop sequelae (see below). Uninfected patients who will have false positive serology will be evaluated and treated generating unnecessary costs.

In the third strategy (presumptive treatment), both infected and uninfected subjects will be treated with praziquantel in a single dose (40 mg/kg, cure rate 75%), and thus, uninfected subjects will create only additional costs and no benefits.

We assumed that untreated infected subjects would develop sequelae in 20% of cases. Since the cure rate of praziquantel is assumed to be 75%, in all the scenarios, some patients (25% of the infected receiving treatment) will have a treated but not completely cured infection. Ninety per cent of those subjects will recover after 5 years as the parasitic infection can be self-extinguishing, while the remaining (10%, assumption) will develop sequelae. A small portion of subjects with ‘cured infection’ (5%, assumption) will not fully recover because of irreversible damage already produced and, therefore, will develop sequelae.

Types of sequelae depend on the infecting Schistosoma specie. We assumed that half of the patients were infected with S. haematobium and half with S. mansoni.

An estimated 1.5% of all sequelae due to S. haematobium are related to progressive kidney failure that will require haemodialysis.22 After 10 years, around 10% of haemodialyzed patients will need kidney transplant,23 while 10% of them will die.24 Moreover, schistosomiasis-associated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the bladder will represent 0.004% of sequelae.25 Other complications due to S. haematobium are minor sequelae such as asymptomatic bladder or urogenital tract abnormalities requiring an annual abdominal US follow-up test.

Also, cases of bleeding gastric varices result from portal hypertension produced by S. mansoni. An estimated 1.7% of all sequelae due to S. mansoni are related to variceal bleeding,22 with a case fatality rate of 20%26 for each episode. Around 12.5% of those who survive the first episode will have a recurrence the following year with the same case fatality rate.26 We assumed that those who survived in the following year in 12·5% of cases would have a recurrence with a case fatality rate of 20% or so in the following years. We assumed all other complications as minor sequelae.

The mean age of appearance of the most important sequelae considered in the model is 39, 34, 52 and 25 years, respectively, for variceal bleeding,27 kidney failure that require haemodyalisis,28 bladder cancer16 and minor sequelae. Their duration is assumed to be 1 year for variceal bleeding and cancer, 10 years for minor sequelae and all life for dialysis (unless a transplant is done).

All data input included in the mathematical model is reported in Supplementary Table S1, Appendix 1.

Utility

A standard utility weighting system was used to calculate survival in terms of QALYs. Utilities represent the quantification of this quality-of-life adjustment, with perfect health assigned a value of 10, and death equal to 0.29 Because of scarcity of literature about quality of life in patients with these specific health conditions, the utilities used were extrapolated from studies involving patients with similar conditions and complications. They are shown in Supplementary Table S2, Appendix 1.

Costs

Regarding the passive diagnosis, we attributed cost α to all symptomatic patients who undergo a specialist infectious diseases consultation, diagnostic test (ELISA IgG) along with parasitological tests of urine and faeces, standard urine test, full blood count, creatinine and ALT.

In the screening strategy, we will have cost β for the diagnostic test (ELISA IgG). The costs of true positive patients will be represented by cost γ (first specialist infectious diseases consultation and parasitological tests) and by the cost of treatment (cost δ). Cost ε represents the cost of a second specialist infectious diseases consultation and of the abdominal US. Cost θ represents the cost of false positive: it contains the costs of the treatment, a parasitological test on urines and faeces, and consultation with an infectious disease specialist. These are only costs for the NHS.

The cost of treatment for patients diagnosed with schistosomiasis in the passive diagnosis strategy and in the screening strategy was that of five tablets of praziquantel once, which corresponded approximately to the standard single dose of 40 mg/kg for subjects with body weight 70 kg (cost δ). The latter along with a second infectious diseases specialist consultation and a US abdomen examination represents the cost ι which is applied to true positive patients in the passive diagnosis strategy. In the presumptive treatment strategy, the cost resulted only from the administration of praziquantel five tablets once, since we supposed that the treatment could be delivered in the context of primary health care (Italian general practitioners are paid a quota per capita that is independent of the number of clinical interventions performed), without a referral to an infectious diseases specialist. Cost ψ represents the cost of sequelae. All costs are shown in Supplementary Table S3, Appendix 1 and in Appendix 2.

The costs of all visits, tests, drugs and interventions were taken from the price list of Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy. In order to approximately estimate the cost of sequelae, several sources were included: a selection of codified possible ‘reasons of hospitalization’ associated with dialysis, kidney transplant and haematemesis, besides literature data for bladder cancer,30 National Drugs Price List for basal and maintenance immunosuppressive therapy, and the price list of Careggi University Hospital for minor sequelae (Appendix 2). All costs are in Euro and referred to 2018 price lists. A discount rate of 3% was applied to all costs and benefits.

Sensitivity analysis

One-way deterministic sensitivity analysis was carried out in order to verify the robustness of results in the base case. This analysis was carried out by ranging single parameter data input (see Supplementary Table S1). In addition, Immunochromatographic test (ICT) (sensitivity: 96%, specificity: 83%, cost: 15 euros) instead of ELISA test was conducted.

Results

The distribution of benefits and costs in the 1- and 28-year scenarios is reported in Table 1. Assuming a population of 100 000 migrants, 21 200 people are infected according to the prevalence rate. As reported in Table 1, the presumptive treatment has a greater clinical impact (bigger number of cured subjects and smaller number of subjects with sequelae) with 86.3% of the infected cured (75.2% in screening programme and 44.9% in passive diagnosis strategy), while the passive diagnosis strategy has not only the lowest cure rate but also the greatest number of sequelae. However, passive diagnosis is also the less expensive strategy in a 1-year time lapse but is the most expensive in a 28-year scenario. In the 28-year perspective, costs of passive diagnosis strategy became comparable with those of the screening strategy, with a lower number of cured subjects and a higher number of sequelae. The least expensive strategy is presumptive treatment.

Table 1

Clinical and economic impact of different strategies for management of schistosomiasis in Sub Sahara African refugees in Italy, 2014–2017

| Survivals | Sequelae | Costs (Euro) 1st year | Total costs (28 years) (discounted) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive diagnosis | 9519 | 2278 | 608 324 | 7 784 534 |

| Screening programme | 15 932 | 1215 | 3 836 480 | 7 662 991 |

| Presumptive treatment | 18 285 | 795 | 2 816 936 | 5 321 197 |

| Survivals | Sequelae | Costs (Euro) 1st year | Total costs (28 years) (discounted) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive diagnosis | 9519 | 2278 | 608 324 | 7 784 534 |

| Screening programme | 15 932 | 1215 | 3 836 480 | 7 662 991 |

| Presumptive treatment | 18 285 | 795 | 2 816 936 | 5 321 197 |

All costs in Euro are referred to 2018 pricelists. Discount rate of 3% was applied to all costs.

Table 1

Clinical and economic impact of different strategies for management of schistosomiasis in Sub Sahara African refugees in Italy, 2014–2017

| Survivals | Sequelae | Costs (Euro) 1st year | Total costs (28 years) (discounted) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive diagnosis | 9519 | 2278 | 608 324 | 7 784 534 |

| Screening programme | 15 932 | 1215 | 3 836 480 | 7 662 991 |

| Presumptive treatment | 18 285 | 795 | 2 816 936 | 5 321 197 |

| Survivals | Sequelae | Costs (Euro) 1st year | Total costs (28 years) (discounted) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive diagnosis | 9519 | 2278 | 608 324 | 7 784 534 |

| Screening programme | 15 932 | 1215 | 3 836 480 | 7 662 991 |

| Presumptive treatment | 18 285 | 795 | 2 816 936 | 5 321 197 |

All costs in Euro are referred to 2018 pricelists. Discount rate of 3% was applied to all costs.

Tables 2 and 3 show QALY calculated by the model. In a 1-year horizon, both the presumptive treatment and the screening strategy when compared with passive diagnosis are very cost-effective. In the 28-year horizon, the two strategies (screening and presumptive treatment) when compared with passive diagnosis become dominant (less expensive with more QALY). In particular, the presumptive treatment becomes cost-saving after 15 years, while the screening strategy does so after 27 years (after 20 years if costs and benefits are not discounted).

Table 2

QALYs of different strategies for management of schistosomiasis

| 1st year | 28 years (discounted) | |

|---|---|---|

| Passive diagnosis | 11 640 | 226 420 |

| Screening programme | 17 063 | 330 545 |

| Presumptive treatment | 19 025 | 368 206 |

| 1st year | 28 years (discounted) | |

|---|---|---|

| Passive diagnosis | 11 640 | 226 420 |

| Screening programme | 17 063 | 330 545 |

| Presumptive treatment | 19 025 | 368 206 |

QALY: quality adjusted life year.

Table 2

QALYs of different strategies for management of schistosomiasis

| 1st year | 28 years (discounted) | |

|---|---|---|

| Passive diagnosis | 11 640 | 226 420 |

| Screening programme | 17 063 | 330 545 |

| Presumptive treatment | 19 025 | 368 206 |

| 1st year | 28 years (discounted) | |

|---|---|---|

| Passive diagnosis | 11 640 | 226 420 |

| Screening programme | 17 063 | 330 545 |

| Presumptive treatment | 19 025 | 368 206 |

QALY: quality adjusted life year.

Table 3

Comparative results of different strategies

| Delta Cost | Delta QALY | Cost/QALY | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st year | |||

| Screening vs Passive diagnosis | 3 228 155 | 5422 | 595 |

| Presumptive treatment vs Passive diagnosis | 2 208 611 | 7385 | 299 |

| 28 years | |||

| Screening vs Passive diagnosis | - 121 544 | 104 125 | DOMINANT |

| Presumptive treatment vs Passive diagnosis | - 2 463 338 | 141 785 | DOMINANT |

| Delta Cost | Delta QALY | Cost/QALY | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st year | |||

| Screening vs Passive diagnosis | 3 228 155 | 5422 | 595 |

| Presumptive treatment vs Passive diagnosis | 2 208 611 | 7385 | 299 |

| 28 years | |||

| Screening vs Passive diagnosis | - 121 544 | 104 125 | DOMINANT |

| Presumptive treatment vs Passive diagnosis | - 2 463 338 | 141 785 | DOMINANT |

QALY: quality adjusted life year.

Table 3

Comparative results of different strategies

| Delta Cost | Delta QALY | Cost/QALY | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st year | |||

| Screening vs Passive diagnosis | 3 228 155 | 5422 | 595 |

| Presumptive treatment vs Passive diagnosis | 2 208 611 | 7385 | 299 |

| 28 years | |||

| Screening vs Passive diagnosis | - 121 544 | 104 125 | DOMINANT |

| Presumptive treatment vs Passive diagnosis | - 2 463 338 | 141 785 | DOMINANT |

| Delta Cost | Delta QALY | Cost/QALY | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st year | |||

| Screening vs Passive diagnosis | 3 228 155 | 5422 | 595 |

| Presumptive treatment vs Passive diagnosis | 2 208 611 | 7385 | 299 |

| 28 years | |||

| Screening vs Passive diagnosis | - 121 544 | 104 125 | DOMINANT |

| Presumptive treatment vs Passive diagnosis | - 2 463 338 | 141 785 | DOMINANT |

QALY: quality adjusted life year.

The sensitivity analysis applied to data input is reported in supplementary Table S1, Appendix 1. The most sensitive data during the first year in the comparison between screening strategy and passive diagnosis are the specificity of IgG Elisa test. The schistosomiasis prevalence is relevant in the comparison between presumptive treatment and passive diagnosis. Cost of serological test (β) and clinical and laboratory assessment of symptomatic patients cost (γ) are the most sensitive costs when screening is compared with passive diagnosis in the first year. Praziquantel cost (δ) is particularly relevant in the presumptive treatment versus current strategy. Changes in the values related to sequelae have no impact on the results. However, the economic profile obtained in the base analysis does not change in the sensitive analysis. In the 28-year perspective, screening and presumptive treatment strategies are almost always dominant over passive diagnosis, independently by the change in the values of data input.

Finally, the use of ICT test (more sensitive, less specific, instead of ELISA test) data is in accordance with the results of the base analysis. The presumptive treatment and the screening strategy when compared with the passive diagnosis are very cost-effective during the first year and they become cost-saving after 28 years.

Discussion

This study aims to offer to healthcare policy-makers an evidence-based approach to the control and management of Schistosoma spp infection in SSA migrants arriving in Italy, which could improve significantly the health of SSA migrant population with a minimum cost to the NHS. We compared the benefits and costs of universal serological screening and universal presumptive treatment with praziquantel to the current strategy of passive diagnosis of symptomatic cases in short and long-time perspectives. The results of the model suggest that in the first-year, both the presumptive treatment and the screening strategy are very cost-effective when compared with current strategy and they become cost-saving after 15 and 27 years, respectively.

Available guidelines in Europe recommend using different strategies to manage schistosomiasis in migrants. While Irish and UK guidelines suggest offering screening only to migrants with symptoms/eosinophilia,31,32 Italian guidelines propose a systematic serological screening test for all migrants exposed in endemic areas but are still not fully covered.33

Outside Europe, US guidelines suggest that asymptomatic SSA refugees who did not receive overseas presumptive praziquantel treatment may be presumptively treated after arrival or screened (‘test and treat’) if contraindications to presumptive treatment exist or if praziquantel is unavailable or inaccessible.34 Australian and Canadian guidelines suggest universal serological screening too.21,35

Recently, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) released guidance on screening and vaccination for infectious diseases in newly arrived migrants in the EU/EEA. The evidence-based statement on schistosomiasis contained in the document suggests offering serological screening and treatment (for those found to be positive) for schistosomiasis to all migrants from countries of high endemicity with a ‘low certainty of evidence’. However, in the above document and also in a recently published systematic review funded by the ECDC, the option of presumptive treatment for schistosomiasis is also discussed and considered likely to be cost-effective on the basis of economic modelling developed in a non-European setting.12 It should be noted that the price of praziquantel used in our model is the current price paid by Italian hospitals to buy the drug in small quantities since it is not registered in Italy and has to be imported.

A recent model study designed for the Canadian setting found that among recently resettled refugees from countries where schistosomiasis was endemic, presumptive treatment was predicted to be less costly and more effective than watchful waiting or screening and treatment; it was also associated with an increase of 0.156 QALY and cost savings of $405 per person, compared with watchful waiting. According to our model, in a 28-year perspective, the presumptive treatment would be associated with an increase of 1.418 QALY per person and savings of 24.633 euros per person.36 Even though presumptive treatment turns out to be the most cost-effective strategy, serological screening and treatment of positive subjects present the advantages of a more targeted and patient-centred approach within the perspective of precision medicine.

The main limitation of our study is that, as in all mathematical models, several assumptions were made due to the lack of some specific data. For example, the validity of the outcome estimates used for the current study could appear questionable since in endemic countries, severe liver and kidney outcomes mostly result from ongoing exposure and increasing worm burden. However, once a person migrates, his worm burden decreases with zero further exposure. Therefore, the likelihood of severe renal and liver complications is different from that observed in endemic populations.

Indeed, among travellers and expatriates infected with schistosomiasis, while symptoms do develop in initially asymptomatic travellers, severe outcomes are exceptionally rare.37 However, our evaluation is focused on adult Sub-Saharan migrants who have been exposed for a significant timeframe during their life to schistosomiasis differently from expatriates and travellers exposed for a short time only. A study by Tilli et al. clearly showed that schistosomiasis was a relevant cause of hospitalization for migrants from SSA, with an estimated hospitalization rate comparable to that for invasive pneumococcal infection in Italy (45 per 100 000 versus 94 per 100 000 population).15,38 The rate of hospitalization is particularly high in migrants coming from certain countries such as Mali (623 per 100 000 population), Guinea Bissau (292 per 100 000 population), Angola (210 per 100 000 population), Guinea (191 per 100 000 population) and the Gambia (139 per 100 000 population).15

Moreover, we used seroprevalence studies to set up the case base scenario assuming the prevalence of the disease to be 21.2%.13 Recent evidence suggests that the prevalence of active infection could be lower in subjects with serology positive and negative parasitological tests.39

However, our data suggest that presumptive treatment would still be cost-effective with the prevalence rate as low as 0.15%. As a matter of fact, at this rate (0.15%), the ICER of screening strategy versus passive diagnosis and that of presumptive treatment versus passive diagnosis would be 42 112 and 52 938 euros per QALY, respectively, in the 1-year perspective, while for the 28-year perspective, both strategies would be dominant leading to cost saving. It should be remembered that in Italy, a threshold of 50 000 euros per QALY is considered for an intervention to be considered cost-effective. Similarly, Webb et al.36 found that presumptive treatment was cost-saving if the prevalence of schistosomiasis in the target population was greater than 2.1%.

Additional benefit from the mass administration of praziquantel to SSA migrants could be the treatment of Taenia solium taeniasis carriers which may theoretically transmit cysticercosis in the receiving country if not treated. In a community-based study carried out in migrant reception centres in Italy, the prevalence of the specific Copro Antigen (CoA) for Theridion solium was 2.6%; however, no cases were confirmed microscopically.40

In conclusion, our cost-effectiveness study supports the adoption of presumptive treatment or serological screening approach in the management of schistosomiasis in non-endemic countries. However, our model should be considerately conservative: for example, we assumed that asymptomatic subjects never had sequelae after the infections.

Conclusions

The results of the model suggest that presumptive treatment and screening strategies with a single dose of praziquantel are more favourable than the current passive diagnosis in the public health management of schistosomiasis in SSA migrants, especially in a longer period analysis. Although with some limitations, due to the nature of the mathematical model and to the assumptions made, this study can be an asset for policymakers to consider not only presumptive treatment but also screening approach as methods to control schistosomiasis in non-endemic high-income countries such as Italy.

Funding

This study was supported by ‘Bando 2016 per finanziamento di progetti competitivi per ricercatori a tempo determinato dell’Università di Firenze’.

Ethical compliance

No approval was required from the ethics committee since the study did not involve patients.

Conflict of interest

The author declare no competing interests. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The funder of the study (University of Florence) had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or in writing the report. The authors had full access to all study data and bore responsibility for the decision to submit the study for publication.

References

World Health Organization

.

Schistosomiasis

.

Available online at

www. who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs115/en/

Meltzer

E

.

Schistosomiasis: still a neglected disease

.

J Travel Med

2021

;

28

:

taab107

PMID: 34254141

.

Colley

DG

,

Bustinduy

AL

,

Secor

WE

,

King

CH

.

Human schistosomiasis

.

Lancet

2014

;

383

:

2253

–

64

.

Warren

KS

,

Mahmoud

AA

,

Cummings

P

,

Murphy

DJ

,

Houser

HB

.

Schistosomiasis mansoni in Yemeni in California: duration of infection, presence of disease, therapeutic management

.

Am J Trop Med Hyg

1974

;

23

:

902

–

9

.

Chabasse

D

,

Bertrand

G

,

Leroux

JP

,

Gauthey

N

,

Hocquet

P

.

Bilharziose à Schistosoma mansoniévolutivedécouverte 37 ans après l'infestation [Developmental bilharziasis caused by Schistosoma mansoni discovered 37 years after infestation]

.

Bull Soc PatholExotFiliales

1985

;

78

:

643

–

7

.

Clerinx

J

,

Van Gompel

A

.

Schistosomiasis in travellers and migrants

.

Travel Med Infect Dis

2011

;

9

:

6

–

24

.

Beltrame

A

,

Guerriero

M

,

Angheben

A

et al.

Accuracy of parasitological and immunological tests for the screening of human schistosomiasis in immigrants and refugees from African countries: An approach with Latent Class Analysis

.

PLoSNegl Trop Dis

2017

;

11

:

e0005593

Published 2017 Jun 5

.

ECDC

.

Public health guidance on screening and vaccination for infectious diseases in newly arrived migrants within the EU/EEA

,

2018

.

Zwang

J

,

Olliaro

P

.

Efficacy and safety of praziquantel 40 mg/kg in preschool-aged and school-aged children: a meta-analysis

.

Parasit Vectors

2017

;

10

:

47

.

Tilli

M

,

Gobbi

F

,

Rinaldi

F

et al.

The diagnosis and treatment of urogenital schistosomiasis in Italy in a retrospective cohort of immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa [published correction appears in Infection. 2019 Mar 4]

.

Infection

2019

;

47

:

447

–

59

.

Agbata

EN

,

Morton

RL

,

Bisoffi

Z

et al.

Effectiveness of Screening and Treatment Approaches for Schistosomiasis and Strongyloidiasis in Newly-Arrived Migrants from Endemic Countries in the EU/EEA: A Systematic Review

.

Int J Environ Res Public Health

2018

;

16

:

11

Published 2018 Dec 20

.

Buonfrate

D

,

Gobbi

F

,

Marchese

V

et al.

Extended screening for infectious diseases among newly-arrived asylum seekers from Africa and Asia, Verona province, Italy, April 2014 to June 2015

.

Euro Surveill

2018

;

23

:

17

–

00527

.

Tilli

M

,

Botta

A

,

Bartoloni

A

,

Corti

G

, Zammarchi L.

Hospitalization for Chagas disease, dengue, filariasis, leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, strongyloidiasis, and Taenia solium taeniasis/cysticercosis, Italy, 2011–2016

.

Infection

.

2020

;

48

:695–713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-020-01443-2. Epub 2020 May 16. PMID:

32418191

.

Koraitim

MM

,

Metwalli

NE

,

Atta

MA

,

el-Sadr

AA

.

Changing age incidence and pathological types of schistosoma-associated bladder carcinoma

.

J Urol

1995

;

154

:

1714

–

6

.

WHO Expert Committee on the Control of Schistosomiasis

,

The control of schistosomiasis: second report of the WHO Expert Committee

,

Geneve

1993

.

Available at:

file:///C:/Users/lorez/Downloads/WHO_TRS_830.pdf

Mantica

G

,

Van der Merwe

A

,

Terrone

C

et al.

Awareness of European practitioners toward uncommon tropical diseases: are we prepared to deal with mass migration? Results of an international survey

.

World J Urol

2020

;

38

:

1773

–

86

.

Marchese

V

,

Beltrame

A

,

Angheben

A

et al.

Schistosomiasis in immigrants, refugees and travellers in an Italian referral centre for tropical diseases

.

Infect Dis Poverty

2018

;

7

:

55

.

Chaves

NJ

,

Paxton

GA

,

Biggs

BA

et al.

The Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases and Refugee Health Network of Australia recommendations for health assessment for people from refugee-like backgrounds: an abridged outline

.

Med J Aust

2017

;

206

:

310

–

5

PMID: 28403765

.

Beby

AT

,

Cornelis

T

,

Zinck

R

,

Liu

FX

.

Cost-effectiveness of high dose hemodialysis in comparison to conventional in-center hemodialysis in the Netherlands

.

Adv Ther

2016

;

33

:

2032

–

48

.

Botelho

MC

,

Alves

H

,

Richter

J

.

Halting Schistosoma haematobium - associated bladder cancer

.

Int J Cancer Manag

2017

;

10

:

e9430

Epub 2017 Sep 30. PMID: 29354800; PMCID: PMC5771257

.

Turon

F

,

Casu

S

,

Hernández-Gea

V

,

Garcia-Pagán

JC

.

Variceal and other portal hypertension related bleeding

.

Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol

2013

;

27

:

649

–

64

.

Costa Lacet

CM

,

Neto

JB

,

Ribeiro

LT

,

Oliveira

FS

,

Wyszomirska

RF

,

Strauss

E

.

Schistosomal portal hypertension: Randomized trial comparing endoscopic therapy alone or preceded by esophagogastric devascularization and splenectomy

.

Ann Hepatol

2016

;

15

:

738

–

44

.

Roure

S

,

Valerio

L

,

Pérez-Quílez

O

et al.

Epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic and economic features of an immigrant population of chronic schistosomiasis sufferers with long-term residence in a non-endemic country (North Metropolitan area of Barcelona, 2002-2016)

,

PLoS One

.

2017

;

12

:

e0185245

Published 2017 Sep 27

.

Torrance

GW

,

Feeny

D

.

Utilities and quality-adjusted life years

.

Int J Technol Assess Health Care

1989

;

5

:

559

–

75

.

Gerace

C

,

Montorsi

F

,

Tambaro

R

et al.

Cost of illness of urothelial bladder cancer in Italy

.

Clinicoecon Outcomes Res

2017

;

Volume 9

:

433

–

42

Published 2017 Jul 24

.

Public Health England

.

Helminth infections: migrant health guide

.

London

:

PHE

,

2017

.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Division of Global Migration and Quarantine. Presumptive Treatment and Screening for Strongyloidiasis, Infections Caused by Other Soil Transmitted Helminths, and Schistosomiasis Among Newly Arrived Refugees

,

2018

. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/70288.

Webb

JA

,

Fabreau

G

,

Spackman

E

,

Vaughan

S

,

McBrien

K

.

The cost-effectiveness of schistosomiasis screening and treatment among recently resettled refugees to Canada: an economic evaluation

.

CMAJ Open

2021

.

Meltzer

E

,

Schwartz

E

.

Schistosomiasis: Current Epidemiology and Management in Travelers

.

Curr Infect Dis Rep

2013

;

15

:

211

–

5

.

Baldo

V

,

Cocchio

S

,

Lazzari

R

et al.

Estimated hospitalization rate for diseases attributable to Streptococcus pneumoniae in the Veneto region of north-east Italy

.

Prev Med Rep

2014

;

15

:

27

–

31

PMID: 27114894; PMCID: PMC4832486

.

Tamarozzi

F

,

Ursini

T

,

Hoekstra

PT

et al.

Evaluation of microscopy, serology, circulating anodic antigen (CAA), and eosinophil counts for the follow-up of migrants with chronic schistosomiasis: a prospective cohort study

.

Parasit Vectors

2021

;

14

:

149

PMID: 33750443; PMCID: PMC7941883

.

Zammarchi

L

,

Tilli

M

,

Mantella

A

et al.

No Confirmed Cases of Taenia solium Taeniasis in a Group of Recently Arrived Sub-Saharan Migrants to Italy

.

Pathogens

2019

;

8

:

296

PMID: 31847324; PMCID: PMC6963956

.

© International Society of Travel Medicine 2022. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please e-mail: [email protected]