Monounsaturated fatty acids, olive oil and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies (original) (raw)

- Research

- Open access

- Published: 01 October 2014

Lipids in Health and Disease volume 13, Article number: 154 (2014)Cite this article

- 40k Accesses

- 318 Citations

- 540 Altmetric

- Metrics details

Abstract

Background

The aim of the present meta-analysis of cohort studies was to focus on monounsaturated fat (MUFA) and cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular mortality as well as all-cause mortality, and to distinguish between the different dietary sources of MUFA.

Methods

Literature search was performed using the electronic databases PUBMED, and EMBASE until June 2nd, 2014. Study specific risk ratios and hazard ratios were pooled using a inverse variance random effect model.

Results

Thirty-two cohort studies (42 reports) including 841,211 subjects met the objectives and were included. The comparison of the top versus bottom third of the distribution of a combination of MUFA (of both plant and animal origin), olive oil, oleic acid, and MUFA:SFA ratio in each study resulted in a significant risk reduction for: all-cause mortality (RR: 0.89, 95% CI 0.83, 0.96, p = 0.001; I2 = 64%), cardiovascular mortality (RR: 0.88, 95% CI 0.80, 0.96, p = 0.004; I2 = 50%), cardiovascular events (RR: 0.91, 95% CI 0.86, 0.96, p = 0.001; I2 = 58%), and stroke (RR: 0.83, 95% CI 0.71, 0.97, p = 0.02; I2 = 70%). Following subgroup analyses, significant associations could only be found between higher intakes of olive oil and reduced risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events, and stroke, respectively. The MUFA subgroup analyses did not reveal any significant risk reduction.

Conclusion

The results indicate an overall risk reduction of all-cause mortality (11%), cardiovascular mortality (12%), cardiovascular events (9%), and stroke (17%) when comparing the top versus bottom third of MUFA, olive oil, oleic acid, and MUFA:SFA ratio. MUFA of mixed animal and vegetable sources per se did not yield any significant effects on these outcome parameters. However, only olive oil seems to be associated with reduced risk. Further research is necessary to evaluate specific sources of MUFA (i.e. plant vs. animal) and cardiovascular risk.

Background

The most common monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) in daily nutrition is oleic acid, followed by palmitoleic acid, and vaccenic acid. Moreover, oleic acid represents the topmost MUFA provided in the diet (~90% of all MUFA). No dietary recommendations for MUFA are given by the National Institute of Medicine, the United States Department of Agriculture, the European Food and Safety Authority and the American Diabetes Association. In contrast, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics as well as the Canadian Dietetic Association both promote <20% MUFA of daily total energy consumption, while the American Heart Association sets a limit of 20% MUFA in their respective guidelines[1–3]. One reason for specific MUFA recommendations might be their potential benefit in the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. However, previous meta-analyses of cohort studies reported inconsistent results of MUFA on coronary heart disease (CHD). Jakobsen et al.[4] observed that replacement of SFA by MUFA marginally increased the risk of coronary events, whereas no significant effects on coronary death could be observed. These results are in strong discrepancy with another meta-analysis of cohort studies, were Mente et al.[5] reported a significant correlation between MUFA intake and a decrease in the relative risk for CHD. Skeaff and Miller[6] did not observe any effects of MUFA-rich diets on relative risks of CHD events and CHD death. Likewise, the most recent meta-analysis by Chowdhury et al. including nine cohort studies found no significant associations between MUFA intake, circulating MUFA and risk of CHD[7].

One explanation for these inconclusive data might be that different sources of MUFA were not taken into account. Adopting a western diet means that MUFA is predominantly supplied by foods of animal origin, while in south European countries, extra virgin olive oil is the most dominant source of this type of fatty acid[8]. Results of the recently published PREDIMED trial demonstrated major cardiovascular benefits of olive oil and nuts when compared to a low-fat diet[9]. As a major outcome parameter, the risk of stroke was reduced, an event which has not been included in the meta-analyses mentioned above. In addition, a recent cohort study observed a significant association between dietary olive oil, higher plasma oleic acid and reduced risk of stroke[10]. Extra virgin olive oil is regarded to be the genuine driver of the Mediterranean diet and was found to be associated with a 26% reduced risk of all-cause mortality in the Spanish branch of the EPIC study[11]. The aim of the present meta-analysis of cohort studies was to focus on MUFA and CVD (combining CHD and stroke), cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality, and to distinguish between the different dietary sources of MUFA (e.g. olive oil).

Materials and methods

Literature search

Queries of literature were performed using the electronic databases PUBMED, and EMBASE (until 2nd June 2014, respectively) with no restrictions to language, and calendar date using the following search terms: (“dietary fat” OR “fatty acids” OR “monounsaturated fat” OR “mufa” OR “olive oil” OR “oleic acid” OR “mediterranean diet”) AND (“cardiovascular disease” OR “myocardial infarction” OR “coronary heart disease” OR “stroke” OR “mortality”) AND (“incidence” OR “cohort” OR “follow-up” OR “prospective” OR “risk ratio” OR “hazard ratio” OR “rate ratio”). Moreover, the reference lists from retrieved articles, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were checked to search for further relevant studies. This systematic review was planned, conducted, and reported in adherence to standards of quality for reporting meta-analyses[12]. Literature search was conducted independently by both authors, with disagreements resolved by consensus.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they met all of the following criteria: (i) cohort study design; (ii) data related to dietary consumption of MUFA, MUFA:SFA ratio, olive oil, and oleic acid; (iii) the primary outcomes were: all-cause mortality, CVD mortality, combined CVD events (cardiovascular mortality, cardiovascular morbidity (non-fatal myocardial infarction, angina, stroke, heart failure, peripheral vascular events)); the secondary outcomes were: coronary heart disease, and stroke; (iv) adjusted relative risks (RRs), and hazard ratios (HRs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) or the data necessary to calculate these; (v) when a study appeared to have been published in duplicate, the version containing the most comprehensive information was selected.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The following data were extracted from each study: the first author’s last name, year of publication, study origin, outcome parameter, sample size, study length, age at entry, sex, specification of MUFA, adjustment factors, quality score, and risk estimates (HR, RR; highest vs. lowest category) with their corresponding 95% CIs. If separate risk estimates for males and females or separate risk estimates for ages were available in one study, the data were pooled and treated as one study. When a study provided several risk estimates, the maximally adjusted model was chosen. To assess the study quality, a 9-point scoring system according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used. Hence, the full score was 9, and a high-quality study in the present analysis was defined by a threshold of ≥ 7 points[[13](/articles/10.1186/1476-511X-13-154#ref-CR13 "Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P: The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. (08.06.2014) http://www.medicine.mcgill.ca/rtamblyn/Readings%5CThe%20Newcastle%20-%20Scale%20for%20assessing%20the%20quality%20of%20nonrandomised%20studies%20in%20meta-analyses.pdf

")\]. Data extraction and quality assessment were performed by one author (L.S).Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was performed by combining the multivariable adjusted RR or HR of the highest compared with the lowest MUFA, MUFA:SFA ratio, oleic acid, or olive oil category based on random effects model using DerSimonian-Laird method, which incorporated both within and between study variability[14]. To ensure a transparent approach to meta-analysis and interpretation of findings in this review, RR/HR estimates for association of fatty acids and primary/secondary outcomes that were often differently reported by each study (such as per-unit or per-1-SD change or comparing quintiles, quartiles, thirds, and other groupings) were transformed, using methods previously described[7]. These transformed estimates consistently corresponded to the comparison of the top versus bottom third of MUFA, MUFA:SFA ratio, olive oil, and oleic acid distribution in each study. To evaluate the weighting of each study, the standard error for the logarithm HR/RR of each study was calculated and regarded as the estimated variance of the logarithm HR/RR using an inverse variance method[14]. Studies were grouped according to the different clinical outcomes (all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, combined cardiovascular events, coronary heart disease, and stroke). Subgroup analysis was performed for total MUFA, MUFA:SFA ratio, oleic acid, and olive oil. Heterogeneity was estimated by the Cochrane Q test together with the I2 statistic. An I2 value >50% indicates substantial heterogeneity across studies[15]. The heterogi command in STATA was used to calculate the confidence intervals for the heterogeneity estimates. Funnel plots were used to assess potential publication bias. To determine the presence of publication bias, we assessed the symmetry of the funnel plots in which mean differences were plotted against their corresponding standard errors. In addition, Egger test was performed to test for potential publication bias[16]. Sensitivity analyses were performed assuming statistical heterogeneity with the metaan command in STATA[17]. All analyses were conducted using the Review Manager by the Cochrane Collaboration (version 5.2) and STATA 13.0 (Stata-Corp, College Station, TX).

Missing data

Dr. Goldbourt (personal communication) provided the 23 year follow-up all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality data of the Israeli civil cohort for the highest vs. lowest quintile MUFA: SFA ratio[18].

Results

Literature search and study characteristics

A total of 32 cohort studies (42 reports) met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis[10, 11, 18–57]. Full search strategy for PUBMED is given in the Additional file1. General study characteristics are given in Table 1. Sample size varied between 161 and 161,808 with a follow-up time ranging from 3.7 to 30 years. The total number of subjects in the included studies was 841,211.

Table 1 General study characteristics of the included cohort studies

Main outcomes

According to the different clinical outcomes, overall risk of all-cause mortality was evaluated in seventeen cohorts, cardiovascular mortality in fourteen cohorts, combined cardiovascular events in twenty-eight cohort studies, coronary heart disease in fifteen cohorts, and stroke in eleven cohorts, respectively.

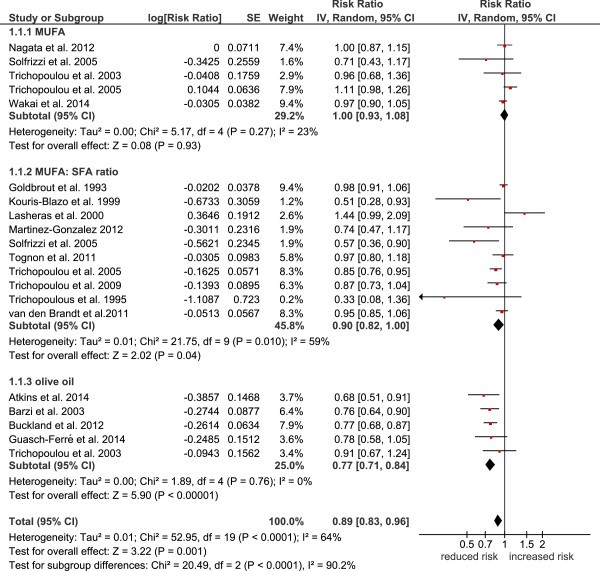

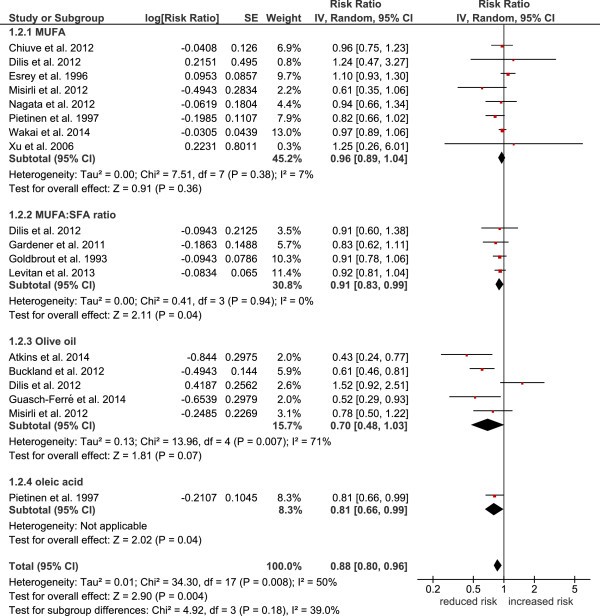

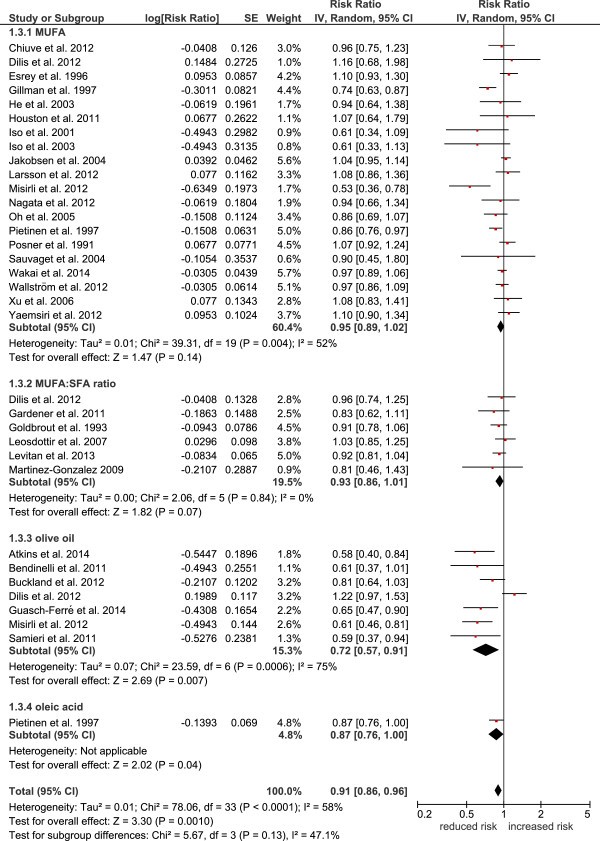

Random effects model data (as summarized in Table 2) revealed that top versus bottom third combined MUFA, olive oil, oleic acid, and MUFA:SFA ratio was significantly associated with a reduced risk of: all-cause mortality (relative risk, RR: 0.89, 95% confidence interval 0.83 to 0.96; p = 0.001, I2 = 64%) (Figure 1), cardiovascular mortality (RR: 0.88, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.96, p = 0.004, I2 = 50%) (Figure 2), combined cardiovascular events (RR: 0.91, 95% CI 0.86 to 0.96, p = 0.001, I2 = 58%) (Figure 3), and stroke (RR: 0.83, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.97, p = 0.02, I2 = 70%). In contrast, no significant changes could be observed for coronary heart disease (RR: 0.96, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.01, p = 0.13, I2 = 41%).

Table 2 Relative risk for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, combined cardiovascular events, stroke, and coronary heart disease (with 95% confidence intervals) comparing the top versus bottom third of MUFA, MUFA:SFA ratio, olive oil, and oleic acid

Figure 1

Forest plot showing pooled relative risks (RRs) with 95% CI for all-cause mortality comparing the top versus bottom third of the distribution of MUFA, MUFA:SFA ratio, olive oil, and oleic acid. I2: Inconsistency; MUFA: monounsaturated fatty acids; SE: standard error; SFA: saturated fatty acids.

Figure 2

Forest plot showing pooled relative risks (RRs) with 95% CI for cardiovascular mortality comparing the top versus bottom third of the distribution of MUFA, MUFA:SFA ratio, olive oil, and oleic acid. I2: Inconsistency; MUFA: monounsaturated fatty acids; SE: standard error; SFA: saturated fatty acids.

Figure 3

Forest plot showing pooled relative risks (RRs) with 95% CI for combined cardiovascular events comparing the top versus bottom third of the distribution of MUFA, MUFA:SFA ratio, olive oil, and oleic acid. I2: Inconsistency; MUFA: monounsaturated fatty acids; SE: standard error; SFA: saturated fatty acids.

Subgroup/sensitivity analyses

Following subgroup analyses, olive oil most likely turned out to be crucial for the results of the primary analysis, since significant associations could only be found between higher intakes of olive oil and reduced risk of all-cause mortality (RR: 0.77, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.84, p < 0.00001, I2 = 0%), cardiovascular events (RR: 0.72, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.91, p = 0.007, I2 = 77%), and stroke (RR: 0.60, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.77, p < 0.0001, I2 = 0%), respectively. Subgroup analysis for MUFA (of mixed animal and plant origin) did not reveal any significant risk reduction for all-cause mortality (RR: 1.00, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.08, p = 0.93, I2 = 23%), cardiovascular mortality (RR: 0.95, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.02, p = 0.14, I2 = 52%), cardiovascular events (RR: 0.96, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.04, p = 0.36, I2 = 7%), coronary heart disease (RR: 0.99, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.06, p = 0.76, I2 = 29%), and stroke (RR: 0.85, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.01, p = 0.07, I2 = 65%). To investigate statistical heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were performed with the metaan command in STATA. Heterogeneity of the main analysis could be confirmed in the sensitivity analyses. Differentiating between studies performed in Europe vs. non-European investigations resulted in significant differences as compared to the main analysis. Pooling European based cohorts resulted in a significant risk reduction for all-cause mortality (RR: 0.87, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.95) as well as for cardiovascular mortality (RR: 0.76, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.91) and cardiovascular events (RR: 0.86, 95% CI 0.78, 0.95). In contrast, no significant reduction in all-cause mortality risk (RR: 0.97, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.04) could be observed for non-European cohorts (the respective data for cardiovascular mortality being RR: 0.94, 95% CI 0.89 to 0.99 and for cardiovascular events being RR: 0.93, 95% CI 0.87 to 0.98). With respect to study length, studies with a follow-up ≥ 10 years resulted in similar results as compared to short-term studies (<10 years follow up). Likewise, high quality studies could confirm the results of the primary analysis.

Publication bias

The Egger’s linear regression tests provided evidence for a potential publication bias for combined cardiovascular events (p = 0.018), all-cause mortality (p = 0.041), and cardiovascular mortality (p = 0.12) following comparison of the top versus bottom third combined MUFA, olive oil, oleic acid, and MUFA:SFA ratio. No evidence of publication bias could be detected for risk of CHD (p = 0.28) and stroke (p = 0.28). All funnel plots indicate little to moderate asymmetry, suggesting that publication bias cannot be completely excluded as a factor of influence on the present meta-analysis (Additional file1: Figures S1, S2, S3, S4 and S5). It remains possible that small studies with inconclusive results have not been published or failed to do so.

Discussion

In the present meta-analysis, comparison of the top versus the bottom third of combined MUFA subgroups (MUFA, olive oil, oleic acid, and MUFA:SFA) was associated with reduced risk of all-cause mortality (11%), cardiovascular mortality (12%), combined cardiovascular events (9%), and stroke (17%). In the ensuing subgroup analyses, this significant correlation could only be observed between higher intakes of olive oil and reduced risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events, and stroke, respectively. In contrast, monounsaturated fatty acids of mixed animal and plant origin did not result in any significant effects with respect to these outcome parameters. Thus, it seems possible that olive oil represents the crucial factor of influence for the protective health effects observed in the primary analysis. However, one has to keep in mind the limitations of the present systematic review and meta-analysis summarized at the end of this section, especially the fact that the specific sources of MUFA have not been indicated in every study.

In order to properly evaluate the potential beneficial or detrimental effects of MUFA with respect to cardiovascular diseases, it seems of importance to consider the source of food providing these fatty acids. In the Nurses’ Health Study, MUFA intake was highly correlated with SFA intake (correlation coefficient of 0.81) but only moderately correlated with intakes of PUFA (correlation coefficient of 0.30), suggesting that fat was primarily of animal origin[58]. In the different EPIC cohorts, MUFA intakes ranged between approximately 10% of daily total energy consumption (TEC) in The Netherlands and ~ 20% of TEC in Greece. In general, intake of MUFA was higher in southern European countries as compared central or northern cohorts. However, another distinguishing feature seems to be the predominant source of MUFA in the respective cohorts. In Greece, Spain, and Italy, fat of plant origin (mainly olive oil) provided up to 64% of MUFA intake, whereas in most other EPIC centers, the main contributors to total MUFA intake were meat and meat products, added fats, and dairy products[8]. This might also provide an explanation for the somewhat mixed results provided by systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the past. Thus, a diet rich in MUFA was found to have beneficial effects on a broad range of CVD risk factors, not only in the primary prevention of CVD[1, 59–61]. On the other hand, no association between total and individual MUFA and CHD was reported in a meta-analysis of studies assessing both dietary intake and circulating fatty acid composition,[7] while a meta-analysis of observational studies suggested that replacing SFAs with PUFAs might have a greater benefit than replacement of SFAs by MUFA[4]. There is some evidence drawn from prospective studies of an adverse association between MUFA and coronary events, but this correlation might be influenced by high amounts of MUFA of animal origin[4].

A number of in-vivo and in-vitro studies examined the health effects of extra virgin olive oil, the potential “Unique Selling Proposition” of a genuine Mediterranean diet. Thus, the Di@bet.es study demonstrated that individuals who consumed olive oil had a significantly lower risk of developing obesity, impaired glucose metabolism, hypertriglyceridemia, and lower HDL cholesterol levels as compared to a group consuming sunflower oil[62]. In addition, results from experimental studies provide evidence that olive oil consumption improves several CHD risk factors[63, 64]. The PREDIMED dietary intervention trial aimed a intake of 50 g/d or more of extra virgin olive oil observed a significant risk reduction of both combined cardiovascular events as well as primary stroke, but not of CHD, indicating a consistency with the results of the present meta-analyses of cohort studies[9]. In a long-term intervention trial by Esposito et al., a higher regression in as well as a lower rate of progression of the intima–media thickness of the carotid artery was found in the group adopting a Mediterranean diet as compared to a low-fat diet reference arm[65].

Apart from oleic acid, olive oil contains a number of bioactive compounds such as polyphenols which are especially prominent in virgin and extra-virgin olive oil, but not in refined olive oil[64, 66]. A key olive oil polyphenol is oleuropein (a compound that generates tyrosol and hydroxytyrosol), which accounts for approximately 80% of olive oil phenolic content and is a potent scavenger of superoxide radicals and inhibits LDL oxidation[67, 68]. There is a causal link between oxidative stress, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and CVD/CHD[69]. A meta-analysis of intervention trials provide evidence that an MD decreases inflammation and improves endothelial function[70]. When focusing on virgin olive oil consumption, the inverse correlation between olive oil and CHD risk found in the present meta-analysis is consistent with the fact that olive oil is not just a supplier of MUFA but of other biologically active components as well.

Several limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the results of the present meta-analysis. MUFA coexist with SFA in several food sources. In addition, cis- and trans-isomers of MUFAs were sometimes categorized together in cohort studies. Furthermore, moderate to substantial heterogeneity could be observed in the present meta-analysis. Potential sources of heterogeneity include combining MUFA/olive oil/oleic acid/MUFA:SFA ratio in the same analysis, heterogeneous risk estimates, heterogeneous populations/ages/gender, sample sizes as well as follow-up periods of the included studies. No unpublished data were considered for the present meta-analysis, and it cannot be excluded that these results may influence the effect size estimates. Examination of funnel plots showed little to moderate asymmetry suggesting that publication bias cannot be completely excluded as a confounder of the present meta-analysis (e.g. it remains possible that small studies yielding inconclusive data have not been published). In addition, the specific food sources of MUFA could not always identified, limiting the validity of any general recommendation towards MUFAs of plant origin (it is most likely olive oil, but it might be other types of food as well, e.g. nuts, canola oil or a specific variety of sunflower oil). Conversely, it might be that results from studies using mixed sources of MUFA might be biased by non-identified olive oil, making MUFA appear to be beneficial in general when some sources are not. Furthermore, observational studies including cohort studies assessing outcome events affected by nutrition should be interpreted with caution, since reliance on nutritional assessment methods with validity and reliability is lower when compared to randomized controlled trials.

However, the present study has some complementary strengths as well. Compared to cohort studies, dietary intervention trials are often limited by lack of double blinding, non-compliance, cross-over, and high drop-out rates. Therefore, well-designed analyses in prospective cohort studies could also provide important evidence with respect to long-term clinical outcomes. Another strength of this work is the inclusion of an overall population >800,000 subjects. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the most comprehensive summary of the evidence on MUFA, olive oil, MUFA:SFA on hard clinical outcome parameters.

Conclusion

The results of the present meta-analysis indicate an overall risk reduction of all-cause mortality (11%), cardiovascular mortality (12%), cardiovascular events (9%), and stroke (17%) when comparing the top vs. bottom thirds of a combination of MUFA, olive oil, oleic acid, and MUFA:SFA ratio. Monounsaturated fat of mixed animal and vegetable sources per se did not yield any significant effects on these outcome parameters. Subgroup analysis indicated that only olive oil (the primary monounsaturated fat source in south European countries) is was associated with a significant risk reduction for several outcomes. These data provide evidence that the source and origin of MUFA within a specific diet should be taken into account in order to evaluate the potential benefits of this type of fatty acids. Further studies are required evaluating specific food sources of MUFA and risk of all-cause mortality and CVD events.

References

- Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G: Monounsaturated fatty acids and risk of cardiovascular disease: synopsis of the evidence available from systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Nutr 2012, 4(12):1989-2007.

CAS Google Scholar - Vannice G, Rasmussen H: Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: dietary fatty acids for healthy adults. J Acad Nutr Diet 2014, 114(1):136-153.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kris-Etherton PM: AHA science advisory. Monounsaturated fatty acids and risk of cardiovascular disease. American heart association. Nutrition committee. Circulation 1999, 100(11):1253-1258.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jakobsen MU, O’Reilly EJ, Heitmann BL, Pereira MA, Balter K, Fraser GE, Goldbourt U, Hallmans G, Knekt P, Liu S, Pietinen P, Spiegelman D, Stevens J, Virtamo J, Willett WC, Ascherio A: Major types of dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of 11 cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2009, 89(5):1425-1432.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mente A, de Koning L, Shannon HS, Anand SS: A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med 2009, 169(7):659-669.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Skeaff CM, Miller J: Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: summary of evidence from prospective cohort and randomised controlled trials. Ann Nutr Metab 2009, 55(1–3):173-201.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chowdhury R, Warnakula S, Kunutsor S, Crowe F, Ward HA, Johnson L, Franco OH, Butterworth AS, Forouhi NG, Thompson SG, Khaw KT, Mozaffarian D, Danesh J, Di Angelantonio E: Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014, 160(6):398-406.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Linseisen J, Welch AA, Ocke M, Amiano P, Agnoli C, Ferrari P, Sonestedt E, Chajes V, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Kaaks R, Weikert C, Dorronsoro M, Rodríguez L, Ermini I, Mattiello A, van der Schouw YT, Manjer J, Nilsson S, Jenab M, Lund E, Brustad M, Halkjaer J, Jakobsen MU, Khaw KT, Crowe F, Georgila C, Misirli G, Niravong M, Touvier M, Bingham S, et al.: Dietary fat intake in the european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition: results from the 24-h dietary recalls. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009, 63(Suppl 4):S61-S80.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, Covas MI, Corella D, Aros F, Gomez-Gracia E, Ruiz-Gutierrez V, Fiol M, Lapetra J, Lamuela-Raventos RM, Serra-Majem L, Pintó X, Basora J, Muñoz MA, Sorlí JV, Martínez JA, Martínez-González MA: Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med 2013, 368(14):1279-1290.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Samieri C, Feart C, Proust-Lima C, Peuchant E, Tzourio C, Stapf C, Berr C, Barberger-Gateau P: Olive oil consumption, plasma oleic acid, and stroke incidence the three-city study. Neurology 2011, 77(5):418-425.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Buckland G, Mayen AL, Agudo A, Travier N, Navarro C, Huerta JM, Chirlaque MD, Barricarte A, Ardanaz E, Moreno-Iribas C, Marin P, Quirós JR, Redondo ML, Amiano P, Dorronsoro M, Arriola L, Molina E, Sanchez MJ, Gonzalez CA: Olive oil intake and mortality within the Spanish population (EPIC-Spain). Am J Clin Nutr 2012, 96(1):142-149.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB: Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000, 283(15):2008-2012.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P: The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. (08.06.2014) http://www.medicine.mcgill.ca/rtamblyn/Readings%5CThe%20Newcastle%20-%20Scale%20for%20assessing%20the%20quality%20of%20nonrandomised%20studies%20in%20meta-analyses.pdf

- DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986, 7(3):177-188.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327(7414):557-560.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar - Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315(7109):629-634.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kontopantelis E, Reeves D: Metaan: random-effects meta-analysis. Stata J 2010, 10(3):395-407.

Google Scholar - Goldbourt U, Yaari S, Medalie JH: Factors predictive of long-term coronary heart disease mortality among 10, 059 male israeli civil servants and municipal employees. A 23-year mortality follow-up in the Israeli ischemic heart disease study. Cardiology 1993, 82(2–3):100-121.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Dilis V, Katsoulis M, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Naska A, Trichopoulou A: Mediterranean diet and CHD: the greek european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition cohort. Br J Nutr 2012, 108(4):699-709.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Trichopoulou A, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D: Anatomy of health effects of Mediterranean diet: greek EPIC prospective cohort study. BMJ 2009, 338: b2337.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar - Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D: Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a greek population. N Engl J Med 2003, 348(26):2599-2608.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Trichopoulou A, Kouris-Blazos A, Wahlqvist ML, Gnardellis C, Lagiou P, Polychronopoulos E, Vassilakou T, Lipworth L, Trichopoulos D: Diet and overall survival in elderly people. BMJ 1995, 311(7018):1457-1460.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Trichopoulou A, Orfanos P, Norat T, Bueno-de-Mesquita B, Ocke MC, Peeters PH, van der Schouw YT, Boeing H, Hoffmann K, Boffetta P, Nagel G, Masala G, Krogh V, Panico S, Tumino R, Vineis P, Bamia C, Naska A, Benetou V, Ferrari P, Slimani N, Pera G, Martinez-Garcia C, Navarro C, Rodriguez-Barranco M, Dorronsoro M, Spencer EA, Key TJ, Bingham S, Khaw KT, et al.: Modified Mediterranean diet and survival: EPIC-elderly prospective cohort study. BMJ 2005, 330(7498):991.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar - Tognon G, Rothenberg E, Eiben G, Sundh V, Winkvist A, Lissner L: Does the Mediterranean diet predict longevity in the elderly? A Swedish perspective. Age (Dordr) 2011, 33(3):439-450.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Guillen-Grima F, De Irala J, Ruiz-Canela M, Bes-Rastrollo M, Beunza JJ, Lopez Del Burgo C, Toledo E, Carlos S, Sanchez-Villegas A: The Mediterranean diet is associated with a reduction in premature mortality among middle-aged adults. J Nutr 2012, 142(9):1672-1678.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lasheras C, Fernandez S, Patterson AM: Mediterranean diet and age with respect to overall survival in institutionalized, nonsmoking elderly people. Am J Clin Nutr 2000, 71(4):987-992.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - van den Brandt PA: The impact of a Mediterranean diet and healthy lifestyle on premature mortality in men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 2011, 94(3):913-920.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Leosdottir M, Nilsson PM, Nilsson JA, Berglund G: Cardiovascular event risk in relation to dietary fat intake in middle-aged individuals: data from the malmo diet and cancer study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007, 14(5):701-706.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Wallstrom P, Sonestedt E, Hlebowicz J, Ericson U, Drake I, Persson M, Gullberg B, Hedblad B, Wirfalt E: Dietary fiber and saturated fat intake associations with cardiovascular disease differ by sex in the malmo diet and cancer cohort: a prospective study. PLoS One 2012, 7(2):e31637.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar - Wakai K, Naito M, Date C, Iso H, Tamakoshi A, Group JS: Dietary intakes of fat and total mortality among japanese populations with a low fat intake: the Japan collaborative cohort (JACC) study. Nutri Metabol 2014, 11(1):12.

Article Google Scholar - Nagata C, Nakamura K, Wada K, Oba S, Tsuji M, Tamai Y, Kawachi T: Total fat intake is associated with decreased mortality in Japanese men but not in women. J Nutri 2012, 142(9):1713-1719.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Chiuve SE, Rimm EB, Sandhu RK, Bernstein AM, Rexrode KM, Manson JE, Willett WC, Albert CM: Dietary fat quality and risk of sudden cardiac death in women. Am J Clin Nutr 2012, 96(3):498-507.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Oh K, Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC: Dietary fat intake and risk of coronary heart disease in women: 20 years of follow-up of the nurses’ health study. Am J Epidemiol 2005, 161(7):672-679.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Atkins JL, Whincup PH, Morris RW, Lennon LT, Papacosta O, Wannamethee SG: High diet quality is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in older men. J Nutr 2014, 144(5):673-680.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Sauvaget C, Nagano J, Hayashi M, Yamada M: Animal protein, animal fat, and cholesterol intakes and risk of cerebral infarction mortality in the adult health study. Stroke 2004, 35(7):1531-1537.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Iso H, Sato S, Kitamura A, Naito Y, Shimamoto T, Komachi Y: Fat and protein intakes and risk of intraparenchymal hemorrhage among middle-aged Japanese. Am J Epidemiol 2003, 157(1):32-39.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Iso H, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Rexrode K, Hu F, Hennekens CH, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Willett WC: Prospective study of fat and protein intake and risk of intraparenchymal hemorrhage in women. Circulation 2001, 103(6):856-863.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Houston DK, Ding J, Lee JS, Garcia M, Kanaya AM, Tylavsky FA, Newman AB, Visser M, Kritchevsky SB, Health ABCS: Dietary fat and cholesterol and risk of cardiovascular disease in older adults: the health ABC study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011, 21(6):430-437.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yaemsiri S, Sen S, Tinker L, Rosamond W, Wassertheil-Smoller S, He K: Trans fat, aspirin, and ischemic stroke in postmenopausal women. Ann Neurol 2012, 72(5):704-715.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Gillman MW, Cupples LA, Millen BE, Ellison RC, Wolf PA: Inverse association of dietary fat with development of ischemic stroke in men. JAMA 1997, 278(24):2145-2150.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Xu J, Eilat-Adar S, Loria C, Goldbourt U, Howard BV, Fabsitz RR, Zephier EM, Mattil C, Lee ET: Dietary fat intake and risk of coronary heart disease: the strong heart study. Am J Clin Nutr 2006, 84(4):894-902.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Esrey KL, Joseph L, Grover SA: Relationship between dietary intake and coronary heart disease mortality: lipid research clinics prevalence follow-up study. J Clin Epidemiol 1996, 49(2):211-216.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Gardener H, Wright CB, Gu Y, Demmer RT, Boden-Albala B, Elkind MS, Sacco RL, Scarmeas N: Mediterranean-style diet and risk of ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and vascular death: the Northern Manhattan Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2011, 94(6):1458-1464.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jakobsen MU, Overvad K, Dyerberg J, Schroll M, Heitmann BL: Dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: possible effect modification by gender and age. Am J Epidemiol 2004, 160(2):141-149.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Garcia-Lopez M, Bes-Rastrollo M, Toledo E, Martinez-Lapiscina EH, Delgado-Rodriguez M, Vazquez Z, Benito S, Beunza JJ: Mediterranean diet and the incidence of cardiovascular disease: a Spanish cohort. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011, 21(4):237-244.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Posner BM, Cobb JL, Belanger AJ, Cupples LA, D’Agostino RB, Stokes J 3rd: Dietary lipid predictors of coronary heart disease in men. The framingham study. Arch Intern Med 1991, 151(6):1181-1187.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - He K, Merchant A, Rimm EB, Rosner BA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Ascherio A: Dietary fat intake and risk of stroke in male US healthcare professionals: 14 year prospective cohort study. BMJ 2003, 327(7418):777-782.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Larsson SC, Virtamo J, Wolk A: Dietary fats and dietary cholesterol and risk of stroke in women. Atherosclerosis 2012, 221(1):282-286.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bendinelli B, Masala G, Saieva C, Salvini S, Calonico C, Sacerdote C, Agnoli C, Grioni S, Frasca G, Mattiello A, Chiodini P, Tumino R, Vineis P, Palli D, Panico S: Fruit, vegetables, and olive oil and risk of coronary heart disease in italian women: the EPICOR study. Am J Clin Nutr 2011, 93(2):275-283.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Barzi F, Woodward M, Marfisi RM, Tavazzi L, Valagussa F, Marchioli R, Investigators GI-P: Mediterranean diet and all-causes mortality after myocardial infarction: results from the GISSI-prevenzione trial. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003, 57(4):604-611.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Solfrizzi V, D’Introno A, Colacicco AM, Capurso C, Palasciano R, Capurso S, Torres F, Capurso A, Panza F: Unsaturated fatty acids intake and all-causes mortality: a 8.5-year follow-up of the Italian longitudinal study on aging. Exp Gerontol 2005, 40(4):335-343.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Misirli G, Benetou V, Lagiou P, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D, Trichopoulou A: Relation of the traditional Mediterranean diet to cerebrovascular disease in a Mediterranean population. Am J Epidemiol 2012, 176(12):1185-1192.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Pietinen P, Ascherio A, Korhonen P, Hartman AM, Willett WC, Albanes D, Virtamo J: Intake of fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease in a cohort of finnish men. The alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene cancer prevention study. Am J Epidemiol 1997, 145(10):876-887.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Guasch-Ferre M, Hu FB, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Fito M, Bullo M, Estruch R, Ros E, Corella D, Recondo J, Gomez-Gracia E, Fiol M, Lapetra J, Serra-Majem L, Muñoz MA, Pintó X, Lamuela-Raventós RM, Basora J, Buil-Cosiales P, Sorlí JV, Ruiz-Gutiérrez V, Martínez JA, Salas-Salvadó J: Olive oil intake and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the PREDIMED study. BMC Med 2014, 12(1):78.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar - Kouris-Blazos A, Gnardellis C, Wahlqvist ML, Trichopoulos D, Lukito W, Trichopoulou A: Are the advantages of the Mediterranean diet transferable to other populations? A cohort study in Melbourne, Australia. Br J Nutr 1999, 82(1):57-61.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Buckland G, Travier N, Barricarte A, Ardanaz E, Moreno-Iribas C, Sánchez MJ, Molina-Montes E, Chirlaque MD, Huerta JM, Navarro C, Redondo ML, Amiano P, Dorronsoro M, Larrañaga N, Gonzalez CA: Olive oil intake and CHD in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Spanish cohort. Br J Nutr 2012, 108(11):2075-2082.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Levitan EB, Lewis CE, Tinker LF, Eaton CB, Ahmed A, Manson JE, Snetselaar LG, Martin LW, Trevisan M, Howard BV, Shikany JM: Mediterranean and DASH diet scores and mortality in women with heart failure: The Women’s Health Initiative. Circ Heart Fail 2013, 6(6):1116-1123.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Rimm E, Colditz GA, Rosner BA, Hennekens CH, Willett WC: Dietary fat intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med 1997, 337(21):1491-1499.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Schwingshackl L, Strasser B: High-MUFA diets reduce fasting glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Nutr Metab 2012, 60(1):33-34.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Schwingshackl L, Strasser B, Hoffmann G: Effects of monounsaturated fatty acids on cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Nutr Metab 2011, 59(2–4):176-186.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Schwingshackl L, Strasser B, Hoffmann G: Effects of monounsaturated fatty acids on glycaemic control in patients with abnormal glucose metabolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Nutr Metab 2011, 58(4):290-296.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Soriguer F, Rojo-Martinez G, Goday A, Bosch-Comas A, Bordiu E, Caballero-Diaz F, Calle-Pascual A, Carmena R, Casamitjana R, Castano L, Castell C, Catalá M, Delgado E, Franch J, Gaztambide S, Girbés J, Gomis R, Gutiérrez G, López-Alba A, Teresa Martínez-Larrad M, Menéndez E, Mora-Peces I, Ortega E, Pascual-Manich G, Serrano-Rios M, Urrutia I, Valdés S, Antonio Vázquez J, Vendrell J: Olive oil has a beneficial effect on impaired glucose regulation and other cardiometabolic risk factors. Di@bet.es study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2013, 67(9):911-916.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Covas MI, Konstantinidou V, Fito M: Olive oil and cardiovascular health. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2009, 54(6):477-482.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lopez-Miranda J, Perez-Jimenez F, Ros E, De Caterina R, Badimon L, Covas MI, Escrich E, Ordovas JM, Soriguer F, Abia R, de la Lastra CA, Battino M, Corella D, Chamorro-Quirós J, Delgado-Lista J, Giugliano D, Esposito K, Estruch R, Fernandez-Real JM, Gaforio JJ, La Vecchia C, Lairon D, López-Segura F, Mata P, Menéndez JA, Muriana FJ, Osada J, Panagiotakos DB, Paniagua JA, Pérez-Martinez P, et al.: Olive oil and health: summary of the II international conference on olive oil and health consensus report, Jaen and Cordoba (Spain) 2008. Nutri Metabol Cardiovasc Dis NMCD 2010, 20(4):284-294.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Esposito K, Giugliano D, Nappo F, Marfella R, Campanian Postprandial Hyperglycemia Study G: Regression of carotid atherosclerosis by control of postprandial hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2004, 110(2):214-219.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Visioli F, Bernardini E: Extra virgin olive oil’s polyphenols: biological activities. Curr Pharm Des 2011, 17(8):786-804.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Perez-Jimenez F, Ruano J, Perez-Martinez P, Lopez-Segura F, Lopez-Miranda J: The influence of olive oil on human health: not a question of fat alone. Mol Nutr Food Res 2007, 51(10):1199-1208.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Visioli F, Bellomo G, Galli C: Free radical-scavenging properties of olive oil polyphenols. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998, 247(1):60-64.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Marin C, Yubero-Serrano EM, Lopez-Miranda J, Perez-Jimenez F: Endothelial aging associated with oxidative stress can be modulated by a healthy mediterranean diet. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14(5):8869-8889.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar - Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G: Mediterranean dietary pattern, inflammation and endothelial function: a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention trials. Nutri Metabol Cardiovasc Dis NMCD 2014, 24(9):929-939.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Nutritional Sciences, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Vienna, Althanstraße 14 (UZAII), A-1090, Vienna, Austria

Lukas Schwingshackl & Georg Hoffmann

Authors

- Lukas Schwingshackl

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Georg Hoffmann

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence toLukas Schwingshackl.

Additional information

Competing interests

Both authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

LS and GH conducted the data analysis, interpretation of results, manuscript drafting, and finalizing manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Schwingshackl, L., Hoffmann, G. Monounsaturated fatty acids, olive oil and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies.Lipids Health Dis 13, 154 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-13-154

- Received: 07 July 2014

- Accepted: 26 September 2014

- Published: 01 October 2014

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-13-154