Global burden of cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases caused by specific etiologies from 1990 to 2021 (original) (raw)

Background

Chronic liver diseases (CLD), including cirrhosis, liver cancer, and other liver disorders, remain a significant public health concern worldwide, contributing to a substantial burden in terms of mortality, morbidity, and healthcare costs. Cirrhosis, characterized by progressive liver fibrosis and eventual liver failure, is a leading cause of global mortality, accounting for nearly 1.5 million deaths annually [1]. In addition, liver cancer, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), is a major consequence of chronic liver disease, exacerbating the global burden of liver-related deaths [2].

Several factors contribute to the rising prevalence of chronic liver diseases globally, the leading etiologies include chronic viral infections such as hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV), alcohol abuse, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [3]. HBV and HCV infections remain the most significant causes of CLD in many low- and middle-income countries, particularly in regions of sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia [4]. HBV-related liver disease has declined in recent years, largely due to widespread vaccination and effective antiviral therapies. In contrast, HCV remains a major challenge, with rising incidences of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in countries with high HCV prevalence [5, 6].

Over the past few decades, the epidemiology of chronic liver diseases in high-income countries has shifted, with NAFLD—primarily driven by obesity and metabolic syndrome—emerging as the leading cause of CLD [7]. This shift has been accompanied by an alarming increase in liver-related morbidity and mortality due to NAFLD-associated cirrhosis and HCC. Similarly, alcohol consumption continues to contribute significantly to the global liver disease burden, particularly in high-income countries and certain regions of Eastern Europe [8].

The global burden of chronic liver disease is compounded by population aging, urbanization, and lifestyle factors such as rising alcohol consumption and unhealthy diets. As populations grow older and rates of obesity and diabetes increase, the burden is projected to rise further in the coming decades, particularly in affected countries [9]. Understanding the current global burden of CLD, the regional differences in disease etiology, and the key risk factors is critical for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies.

This study aims to provide an updated estimate of the global burden of cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases from 1990 to 2021, focusing on the impact of specific etiologies, including HBV, HCV, alcohol use, and NAFLD. Unlike previous GBD 2021–based studies, such as those by Tham et al. (2025) [10] and Guo et al. (2024) [11], which had shorter timeframes or focused on a single etiology, our analysis spans 1990–2021 and compares four major etiologies with detailed country-level and SDI-specific patterns. By analyzing the trends in incidence, prevalence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), this study seeks to provide an evidence-based foundation for policymaking and strategic planning aimed at mitigating the global burden of liver disease.

Methods

overview and data collection

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study applies standardized modeling frameworks, including the Cause of Death Ensemble Model (CODEm), the Bayesian meta-regression tool DisMod-MR 2.1, and Spatiotemporal Gaussian Process Regression (ST-GPR), to generate comparable estimates across countries and years. These models integrate diverse data sources—such as vital registration, surveys, registries, and published studies—while adjusting for underreporting and misclassification. All estimates undergo cross-validation by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) to reduce bias from variations in data quality across regions. For this study, we accessed the GBD Results Tool to retrieve the relevant data. Specifically, we selected “Cause of Death or Injury” under the GBD Estimate directory; “Incidence”, “Prevalence,” “Deaths,” “DALYs (Disability-Adjusted Life Years),” under the Measure directory; “Number” and “Rate” under the Metric directory; “Cirrhosis and Other Chronic Liver Diseases” under the Cause directory; “All countries and territories” under the Location directory; “1–95 + years” and “ALL-age standardized” under the Age directory; and “Both,” “Female,” and “Male” under the Sex directory, with data spanning from 1990 to 2021 under the Year directory. Age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR), prevalence rate (ASPR), mortality rate (ASMR), and disability-adjusted life years rate (ASDR) were obtained from the GBD 2021 study and calculated using the direct age-standardization method, applying age-specific rates for each 5-year age group to the GBD standard population. The formula is: ASR = (Σ (wᵢ × rᵢ))/(Σ wᵢ) where rᵢ is the age-specific rate and wᵢ is the standard population weight. ASIR represents new cases per 100,000 population/year, ASPR represents existing cases at a specific time, ASMR represents deaths/year, and ASDR represents DALYs/year. DALYs are the sum of years of life lost (YLL = N × L) and years lived with disability (YLD = P × DW), where N is the number of deaths, L is standard life expectancy, P is prevalence, and DW is disability weight. Following the data extraction, we exported the raw data for analysis.

SDI classification

For the purpose of this study, the Socio-Demographic Index (SDI), a composite metric that includes income per capita, average years of schooling for individuals aged 15 and above, and fertility rates for females aged under 25, was utilized to classify countries by socio-economic development. This index, introduced in GBD 2021, classifies countries into five categories based on their SDI values in 2021: low SDI (< 0.455), low-middle SDI (≥ 0.455 and < 0.608), middle SDI (≥ 0.608 and < 0.690), high-middle SDI (≥ 0.690 and < 0.805), and high SDI (≥ 0.805). This classification allows for a better understanding of the relationship between socio-economic development and the burden of cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases.

Data analysis

The primary metrics used to characterize the burden of cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases were incidence, prevalence, deaths, DALYs, along with their respective rates per 100,000 population. Each rate is presented with a 95% uncertainty interval (UI), which was computed using the methodology applied by the GBD initiative. To examine temporal patterns, we calculated the mean estimated annual percentage changes (EAPCs) to identify trends in disease burden over time. The EAPC was calculated by fitting a linear regression model to the natural logarithm of age-standardized rates over the study period, with 95% confidence intervals derived from the regression slope to assess trend significance. A negative upper limit of the EAPC and its corresponding 95% CI indicates a decreasing trend, while a positive lower limit of both the EAPC and 95% CI suggests an increasing trend in the respective rate.

A Bayesian age–period–cohort (BAPC) model was ues to project esophageal cancer incidence. Age-specific incidence rates were organized into Lexis diagrams with 5-year age groups, and Bayesian inference was performed using integrated nested Laplace approximation (INLA). Age, period, and cohort effects were modeled with second-order random walk priors to ensure smoothness, and age-standardized rates were calculated using the GBD world standard population.

To explore associations between disease burden metrics (including incidence rate, DALYs, etc.) and SDI values across different regions, we performed loess regression analysis, which provides a smooth curve for modeling non-linear relationships. These analyses were performed using R version 4.3.1, and results were considered statistically significant for two-tailed p-values of less than 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This study utilizes publicly available data from the Global Burden of Disease database, ensuring that no individual patient data was involved. All procedures for data use and analysis adhered to the ethical guidelines for health data research, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington (Seattle, WA, USA).

Results

Global incidence, prevalence, mortality and DALYs

To provide context for the burden estimates, the global population increased from approximately 5.33 billion in 1990 (95% CI: 5.23–5.44 billion) to 7.89 billion in 2021 (95% CI: 7.67–8.13 billion). In 2021, the global incidence of cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases was estimated at 58.42 million cases (95% UI 54.23 to 62.80), with the ASIR at 724.31 per 100,000 persons (95% UI 672.98 to 779.55). Among the causes, NAFLD-related cirrhosis had the highest ASIR (592.78, 95% UI 542.23 to 643.24), while alcohol-related cirrhosis showed the lowest (5.34, 95% UI 4.40 to 6.25). From 1990 to 2021, ASIR for cirrhosis due to NAFLD was the only etiology that exhibited an upward trend (EAPC = 0.73), others declined, such as cirrhosis due to hepatitis B (EAPC = − 2.74), hepatitis C (EAPC = − 0.51) and alcohol use (EAPC = − 0.78) (Table 1).

Table 1 Global incidence, prevalence, mortality, and DALYs of liver cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases from 1990 to 2021

Global prevalence of cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases in 2021 reached approximately 1.70 billion (95% UI 1.58 to 1.82 billion), with the ASPR at 20,302.62 per 100,000 persons (95% UI 18,845.23 to 21,791.91). NAFLD-related cirrhosis also remained the most prevalent, while alcohol-related cirrhosis showed the lowest with an ASPR of 34.81 (95% UI 28.88 to 40.26). An estimated 1.43 million (95% UI 1.31 to 1.56 million) deaths were attributed to cirrhosis and chronic liver diseases in 2021, with an ASMR of 16.64 per 100,000 (95% UI 15.28 to 18.26). HBV remained the leading cause of liver-related deaths (ASMR = 5.03, 95% UI 4.26–5.85), followed by HCV and alcohol use, NAFLD exhibited the lowest ASMR, highlighting a marked contrast despite its rising incidence. From 1990 to 2021, the ASMR declined across all etiologies except NAFLD, which remained relatively stable (EAPC = − 0.03). Globally, cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases accounted for 46.42 million DALYs in 2021. The ASDR was 545.07 per 100,000 persons (95% UI 506.13 to 594.99), HBV was the major contributor, followed by HCV. Over the past three decades, ASDR showed significant downward trends for all causes except NAFLD, which slightly increased (EAPC = 0.04), suggesting a shifting burden from viral to metabolic origins (Table 1).

Regional burden of cirrhosis and chronic liver diseases in 2021

In 2021, NAFLD was the leading global cause of cirrhosis. The North Africa and Middle East region recorded the highest ASIR of cirrhosis due to NAFLD, at 1,037.00 per 100,000 population (95% UI: 962.40 to 1,109.01). This region also had the highest ASPR from NAFLD, at 27,686.02 per 100,000 (95% UI: 25,586.19–29,913.98), and the EAPC of ASIR of NAFLD related cirrhosis was 0.7, reflecting both the widespread impact and the prolonged disease duration in this population (Table 2, Table S2).

Table 2 Regional incidence and ASIR of liver cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases in 2021

Regarding the overall impact of NAFLD, the Andean Latin America region recorded the highest ASMR in 2021, at 5.52 per 100,000 population (95% UI: 3.72 to 7.68), corresponding to approximately 3,229.94 deaths (95% UI: 2,173.78 to 4,487.74), and the EAPC of that was 0.72. Eastern Europe exhibited the highest EAPC of ASMR of NAFLD-related cirrhosis, reaching 3.8 (Table 2, Table S2, Figure S2). Despite lower incidence rates compared to some other regions, this elevated EAPC of ASMR suggests more severe disease progression or inadequate management.

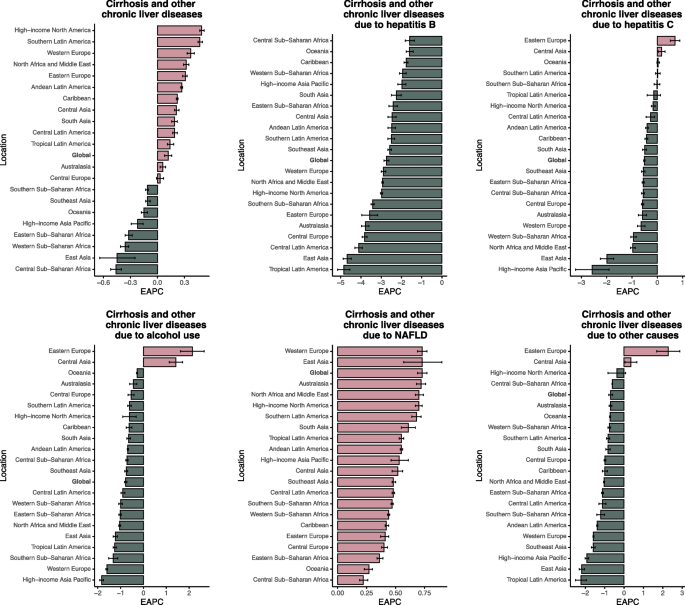

In 2021, Central Sub-Saharan Africa recorded the highest ASMR for cirrhosis and chronic liver diseases globally, at 40.30 per 100,000 population (95% UI: 30.31–51.17), corresponding to 27,615 deaths (95% UI: 20,509–34,947) (Table S4). The ASDR in this region was the highest, at 1,298.27 (95% UI: 969.14–1,639.60), corresponding to a total of 1.08 million DALYs (95% UI: 0.81–1.37 million) (Table S5). HBV accounted for 9,168 deaths (95% UI: 6,214–12,706; ASMR 13.46, 95% UI: 9.15–18.23) and an ASDR of 432.70 (95% UI: 294.65–599.22). HCV caused 9,440 deaths (95% UI: 6,653–13,044) and an ASDR of 445.67 (95% UI: 314.98–615.06).However, the EAPC of ASIR, ASPR, ASMR, ASDR were all decline, representing the overall reduction in disease burden in this region (Table 2, Table S1-S2, Fig. 1, Figure S1-S3).

Fig. 1

The EAPC of ASIR for liver cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases in global and 21 regions. ASIR age-standardized incidence rate, EAPC estimated annual percentage change, NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

In 2021, the highest burden of alcohol-related liver disease was observed in Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and Andean Latin America. Central Asia recorded the highest ASIR at 18.56 (95% UI: 14.78 to 22.14), ASPR of 105.74 (95% UI: 84.11 to 127.61), and ASMR of 11.63 (95% UI: 9.26 to 14.28), with a total of 336,682.02 DALYs (95% UI: 257,713.33–419,178.25) (Table 2, Table S3-S5). Eastern Europe reported the highest ASDR, at 393.33 (95% UI: 340.11–449.44). Andean Latin America followed with an ASIR of 13.06 (95% UI: 10.58–15.24), ASPR of 66.30 (95% UI: 52.52–78.67), and ASMR of 9.72 (95% UI: 7.27–12.71) (Table 2, Table S2-S5, Figure S3).

Regional distribution of ASIR, ASPR, ASMR, and ASDR by SDI level

In 2021, the ASIR of cirrhosis and chronic liver diseases exhibited a nonlinear association with the SDI, following an inverted U-shaped pattern. ASIR remained relatively stable with SDI up to approximately 0.6 and then declined as SDI approached 0.9. Across etiologies, The decline in HBV-related cirrhosis incidence was mainly observed in countries with SDI < 0.65, and this decreasing trend plateaued in countries with SDI ≥ 0.65. HCV-related ASIR declined consistently with increasing SDI. Alcohol-related ASIR was highest in regions with SDI between 0.45–0.7, including Central and Eastern Europe. NAFLD-related ASIR showed a continuous upward trend across the SDI spectrum up to 0.6 (Fig. 2).

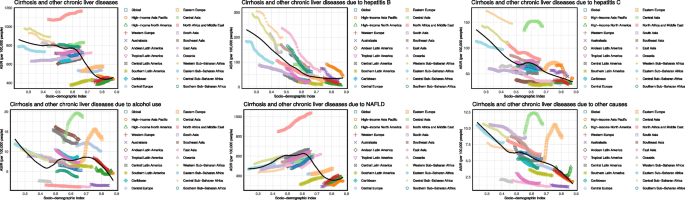

Fig. 2

ASIR of liver cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases by SDI. ASIR age-standardized incidence rate, SDI sociodemographic index, NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

The ASPR of cirrhosis also decreased steeply. HBV and HCV-related ASPR was highest in low and low-middle SDI regions and declined sharply in middle SDI areas. Alcohol-related ASPR, ASMR, ASDR peaked around SDI 0.75, with a slight decline thereafter. NAFLD-related ASMR and ASDR demonstrated a fluctuating pattern across the SDI range and was highest in middle SDI regions(Figure S4-S6).

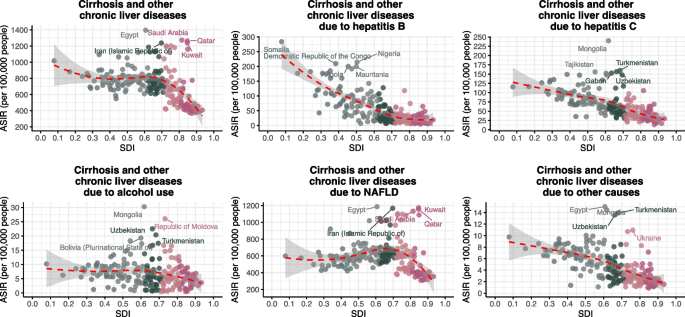

Country distribution of ASIR, ASPR, ASMR, and ASDR by SDI level

In 2021, countries at different levels of SDI exhibited a nonlinear distribution in the ASIR of cirrhosis and chronic liver diseases. Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar exhibited the highest overall ASIRs despite middle-to-high SDI. For HBV-related cirrhosis, the highest ASIRs were observed in low-SDI countries such as Somalia, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. HCV-related ASIRs were concentrated in Central Asia, with Mongolia, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan leading. Alcohol-related ASIRs were highest in Mongolia and Moldova. NAFLD-related ASIRs peaked in Middle Eastern countries including Egypt and Kuwait (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3

ASIR of liver cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases for 204 countries and territories by SDI. ASIR age-standardized incidence rate, SDI sociodemographic index, NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

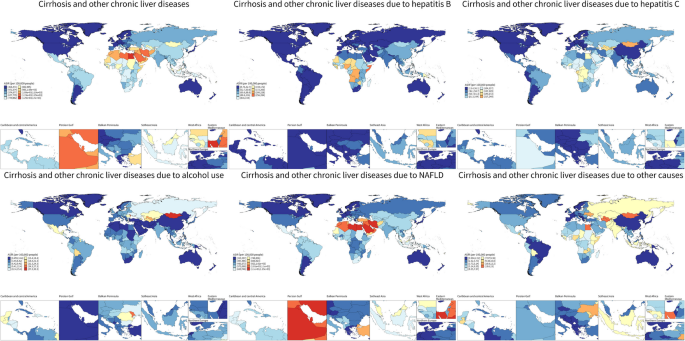

Fig. 4

The ASIR of liver cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases per 100,000 populations in 2021, by country and territory. ASIR age-standardized incidence rate, NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

ASPR followed a similar geographic distribution. Egypt and Gulf countries such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Qatar showed the highest ASPRs for total cirrhosis. HBV-related ASPRs were highest in Somalia, Chad, and Niger. HCV-related ASPRs were most elevated in Mongolia, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Moldova and Ukraine showed the highest ASPRs for alcohol-related cirrhosis. NAFLD-related ASPRs were concentrated in oil-rich countries such as Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, while ASPRs for other causes were elevated in Central Asian countries including Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan (Figure S7, Figure S10).

ASMR patterns showed that Egypt had the highest overall cirrhosis-related mortality, followed by countries such as Somalia and the Central African Republic. HBV-related ASMRs were highest in these low-SDI African nations. HCV-related ASMRs were most prominent in Egypt and the Central African Republic. Alcohol-related ASMRs were highest in Turkmenistan, Moldova, Kazakhstan, and Romania. NAFLD-related ASMRs peaked in Egypt, Mexico, and Bolivia (Figure S8, Figure S11). Egypt had a markedly high total ASDR at an SDI of ~ 0.6, primarily due to HCV, for which it ranked among the highest globally. HBV-related ASDRs exceeded 600–800 per 100,000 in Somalia, Egypt, and the Central African Republic (Figure S9, Figure S12).

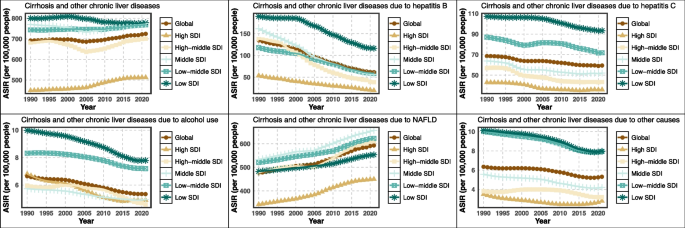

Temporal trends in ASIR, ASPR, ASMR, and ASDR across SDI levels

From 1990 to 2021, the global ASIR of cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases remained relatively stable overall but varied significantly by SDI level. ASIR declined in low and low-middle SDI regions, particularly for HBV-related cirrhosis. In contrast, high and high-middle SDI regions showed slight increases in ASIR, primarily driven by NAFLD. HCV-related ASIR remained elevated in middle SDI countries. Alcohol-related ASIR gradually increased in low-middle SDI regions. NAFLD-related ASIR showed a continuous upward trend across all SDI quintiles, with the steepest rise in high SDI areas (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

The temporal trends of ASIR for liver cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases in different SDI regions from 1990 to 2021. ASIR age-standardized incidence rate, SDI sociodemographic index, NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

The global ASPR of alcohol-related cirrhosis increased modestly from 1990 to 2020, with the highest ASPRs recorded in high and high-middle SDI regions. In high-middle SDI countries, alcohol-related ASPR rose sharply from 1990 to 2000, increased more slowly from 2000 to 2010, and began to decline after 2010. HBV-related ASPR declined across all SDI groups, most notably in high and middle SDI countries. HCV-related ASPR declined steadily in high SDI regions but remained elevated in low and middle SDI areas. NAFLD-related ASPR increased across all SDI groups, surpassing alcohol as the leading cause in high-income settings.

From 1990 to 2021, global ASMR for cirrhosis decreased slightly overall. HBV-related ASMR declined across all SDI categories, especially in low and low-middle SDI regions. HCV-related ASMR showed a consistent decline in high SDI regions. NAFLD-related ASMR increased between 1990–1995 and 2000–2005. From 1990 to 2020, NAFLD-related ASDR demonstrated variability across SDI strata, with a general upward trend globally and more pronounced fluctuations in high-middle SDI regions.The overall cirrhosis burden, in terms of ASDR, remained highest in low-SDI regions, predominantly due to viral hepatitis (Figure S13-S15).

EAPC of ASIR, ASPR, ASMR, and ASDR in countries

In 2021, ASIR for cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases demonstrated substantial geographical variation. The highest overall ASIRs were observed in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, while most high-income countries, including those in Western Europe, North America, and Australasia, showed low ASIRs. The largest declines in ASIR occurred in Zimbabwe (EAPC = –0.75), Rwanda (–0.70), and Cambodia (–0.57). HBV-related ASIRs were highest in Somalia, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The most pronounced decreases in HBV-related ASIR were reported in Poland (EAPC = –5.77), Brazil (–4.89), and Italy (–4.87). HCV-related ASIRs were highest in Mongolia, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Alcohol-related ASIRs peaked in Mongolia, Republic of Moldova, and Uzbekistan, while NAFLD-related ASIRs were highest in Egypt, Kuwait, and Iran. The greatest increases in NAFLD-related ASIR were observed in Equatorial Guinea (EAPC = 1.19), Oman (0.99), and Iran (0.94). The most significant decline in alcohol-related ASIR was recorded in the Republic of Korea (EAPC = –4.05) (Table S6). In terms of ASDR, the highest increases in 2021 were found in the Russian Federation (EAPC = 3.47), Belarus (3.22), and Lithuania (3.05). The largest declines were reported in Republic of Korea (–5.71), Singapore (–5.01), and Maldives (–4.52) (Table S6-S9).

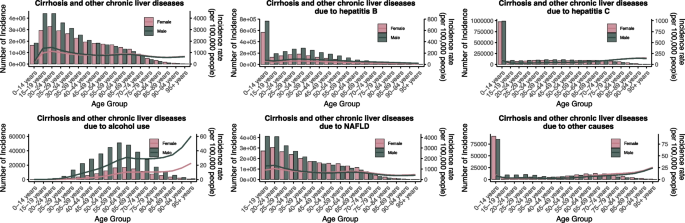

Sex- and age-specific incidence, prevalence, mortality, and DALYs

In 2021, the ASIR of total cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases increased progressively with age, with peaks observed in the 20–24 and 65–69 age groups for both sexes. Males consistently exhibited higher ASIRs than females across all age groups. HBV-related ASIR was highest among individuals aged 0–14 years, with males bearing a significantly greater burden. HCV-related ASIR showed a similar age pattern but with lower incidence levels than HBV. Alcohol-related ASIR rose sharply from age 30, peaking between 55–64 years, with the highest burden observed in males aged 50–69. NAFLD-related ASIR increased steadily with age and plateaued between 65–74 years, showing a relatively balanced sex distribution with slightly higher rates in males (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6

Global incidence of liver cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases by age and sex in 2021. NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

ASPR of total cirrhosis increased with age, reaching its highest point in the 65–69 age group for both sexes. Males showed higher ASPRs than females across all age strata. HBV-related ASPR gradually increased from young adulthood and peaked at ages 30–34, with males experiencing markedly higher prevalence. HCV-related ASPR exhibited a more balanced distribution between sexes. Alcohol-related ASPR increased sharply beginning in the 30 s, peaking at ages 55–64, with male prevalence several times higher than that of females. NAFLD-related ASPR rose progressively with age, reaching a plateau between 65–74 years, with similar levels in both sexes. ASMR for cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases increased progressively with age, peaking between 60–69 years. Males consistently showed higher ASMRs across all age groups. NAFLD-related ASMR remained lower than that of viral hepatitis and alcohol-related causes, despite high global prevalence. Mortality due to NAFLD rose gradually with age and peaked at 70–79 years(Figure S16-S18).

Globally, from 1990 to 2021, ASDR and DALY rates for cirrhosis declined, whereas ASIR and ASPR showed heterogeneous trends by etiology. NAFLD surpassed HBV as the leading cause of incident cirrhosis cases, with notable regional disparities: the highest mortality was observed in Central Sub-Saharan Africa and Mongolia, and the lowest in high-SDI regions.

Using Bayesian age–period–cohort modeling, we forecasted cirrhosis burden through 2025. The projections indicate that HBV-related cirrhosis will continue its marked downward trajectory, with a rapid decline evident by 2025, reflecting the sustained impact of vaccination programs and the broad availability of antiviral therapy. In contrast, NAFLD-related cirrhosis demonstrates a persistent upward trend, with projections suggesting further increases by 2025. This divergence underscores a shifting etiological landscape in which metabolic liver disease is gradually replacing viral hepatitis as the dominant driver of cirrhosis burden(Figure S19).

Discussion

This study provides an updated assessment of the global burden of cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases from 1990 to 2021, focusing on the impact of key etiologies, including HBV, HCV, alcohol use, NAFLD, and other causes. Our findings reveal substantial regional variations in disease burden and highlight an evolving landscape of liver diseases worldwide.

The global burden of cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases has increased significantly, driven primarily by rising incidence and prevalence in high-SDI regions such as North America and Western Europe. Notably, the decline in HBV-related cirrhosis—largely attributed to successful vaccination programs and the widespread availability of antiviral treatments—has contributed significantly to the stabilization of the disease burden in many regions [12]. However, HCV continues to pose a major public health challenge, particularly in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, where HCV-related cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remain prevalent [13, 14].

However, regions with the highest ASMR, such as Central Sub-Saharan Africa, likely face multiple challenges including limited healthcare infrastructure, delayed diagnosis, low antiviral therapy coverage, and restricted access to liver transplantation. The disproportionately high burden of HBV-related cirrhosis in Africa and low-SDI regions underscores the urgent need for expanded vaccination programs, improved access to antiviral therapies, and effective strategies to prevent vertical transmission [15,16,17]. In these regions, HBV remains a leading cause of cirrhosis and liver cancer, exacerbated by inadequate healthcare infrastructure and limited access to effective interventions. In contrast, high-SDI regions have made significant progress in addressing HBV-related liver disease, yet new challenges have emerged, with NAFLD-related cirrhosis now becoming the predominant cause of liver disease in these areas, driven by lifestyle factors and the ongoing obesity epidemic [18, 19]. In addition to true epidemiological changes, part of the observed increase in NAFLD-related burden may be attributable to changes in diagnostic criteria, increased clinician awareness, and broader use of diagnostic tools such as ultrasound and elastography. The recent redefinition from NAFLD to MAFLD/MASLD has also expanded case identification, which may influence temporal trends. As seen in our findings, the rising trends in NAFLD-related cirrhosis in middle-SDI regions call for urgent public health interventions aimed at managing metabolic syndrome and promoting healthier lifestyles [20]. The shift from HBV to NAFLD as the leading cause of incident cirrhosis highlights the need to rebalance healthcare priorities. In low- and middle-SDI regions, sustaining HBV vaccination, completing immunization schedules, and expanding antiviral coverage remain cost-effective, while scaling up HCV screening and direct-acting antivirals(DAA) access is crucial. For NAFLD, integrating risk-based screening into primary care, especially for high-risk groups, and implementing structured lifestyle interventions are essential. Given the higher long-term costs of NAFLD-related disease compared with viral hepatitis prevention programs, budget allocation should maintain investments in viral hepatitis elimination while increasing resources for metabolic risk factor control. Incorporated data from systematic reviews and real-world programs showing significant improvements in body weight, hepatic steatosis, and fibrosis risk reduction through intensive lifestyle interventions, while also acknowledging the absence of long-term RCTs with hard outcomes [21, 22]. Different etiologies of cirrhosis often co-exist and interact; for instance, metabolic risk factors can accelerate fibrosis progression in individuals with viral hepatitis or alcohol use. As viral hepatitis control improves, the relative contribution of NAFLD and alcohol-related liver disease is likely to increase, shifting the overall etiology profile over time. Current guidelines highlight the importance of universal HBV birth-dose vaccination, one-time HCV screening with linkage to simplified DAA therapy, and targeted NAFLD screening in high-risk groups such as those with obesity or diabetes. Implementation at scale will require broader access to non-invasive diagnostic tools and strengthening of multidisciplinary healthcare capacity [23, 24]. It should be noted that the burden of NAFLD and alcohol-related liver disease may be underestimated in our analysis due to underdiagnosis, especially in low-resource regions where diagnostic capacity, routine screening, and awareness among healthcare providers are limited. Alcohol-related liver disease remains a critical issue, particularly in high-income countries and certain parts of Eastern Europe. Despite efforts to reduce alcohol consumption through public health campaigns, alcohol continues to be a major contributor to liver-related morbidity and mortality, underscoring the need for more effective prevention strategies [25]. Our findings are consistent with previous research, which has identified alcohol consumption as a persistent driver of liver-related deaths in these regions [26].

Our study also underscores the importance of the Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) in shaping the distribution of liver disease burden. The relationship between SDI and liver disease prevalence is evident, with high-SDI regions, such as Western Europe and North America, experiencing higher rates of NAFLD, while low-SDI regions, particularly sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, continue to bear the highest burden of HBV and HCV-related cirrhosis. The inverted U-shaped relationship between SDI and cirrhosis burden suggests that middle-SDI regions bear a dual burden of infectious and metabolic etiologies, while NAFLD incidence continues to rise with SDI up to ~ 0.6, highlighting the need for tailored interventions across different development stages. These findings illustrate that cirrhosis burden varies not only by cause but also by level of socio-demographic development, with distinct inflection points that reflect global inequalities in risk exposure, health system performance, and disease prevention strategies.

Age and gender disparities in liver disease burden also merit attention. Our analysis revealed that liver disease primarily affects individuals aged 40–64 years, with men consistently exhibiting higher rates of incidence and mortality compared to women, particularly for alcohol-related liver disease and NAFLD [27, 28]. These findings highlight the need for tailored public health strategies, particularly targeting middle-aged men who are at elevated risk.

In economic aspects, for hepatitis B, timely administration of the birth-dose vaccine is highly cost-effective, with modelling studies in sub-Saharan Africa showing an incremental cost of approximately 110perDALYaverted—farbelowthe2018GDPpercapitathreshold—andanalysesinrefugeesettingsreportinganincrementalcost−effectivenessratios(ICERs)aslowas110 per DALY averted—far below the 2018 GDP per capita threshold—and analyses in refugee settings reporting an incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) as low as 110perDALYaverted—farbelowthe2018GDPpercapitathreshold—andanalysesinrefugeesettingsreportinganincrementalcost−effectivenessratios(ICERs)aslowas0.11–0.16 per life-year saved [29]. For hepatitis C, DAAs achieve > 90% cure rates and have demonstrated substantial cost savings. Real-world experience in Cambodia confirmed that DAA scale-up achieved cost savings within 5 years [30], while in Japan compared with no treatment, the ICER of DAAs at a price USD 41,046 per treatment was USD 9,080 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained in 60-year-old patients [31]. Emerging evidence highlights the substantial economic burden of NAFLD. A systematic review estimated that the annual direct medical costs of NAFLD and NASH in the United States reached 103billion,whileinfourEuropeancountries(Germany,France,Italy,UnitedKingdom)combinedcostswere€35billion.Indirectcosts,includingreducedproductivityanddisability,furtherexacerbatethisburden.Cost−of−illnessmodelssuggestthatadvancedstagessuchascirrhosisandhepatocellularcarcinomacontributedisproportionatelytoexpenditures,withlifetimecostsforNASHcirrhosisexceeding103 billion, while in four European countries (Germany, France, Italy, United Kingdom) combined costs were €35 billion. Indirect costs, including reduced productivity and disability, further exacerbate this burden. Cost-of-illness models suggest that advanced stages such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma contribute disproportionately to expenditures, with lifetime costs for NASH cirrhosis exceeding 103billion,whileinfourEuropeancountries(Germany,France,Italy,UnitedKingdom)combinedcostswere€35billion.Indirectcosts,includingreducedproductivityanddisability,furtherexacerbatethisburden.Cost−of−illnessmodelssuggestthatadvancedstagessuchascirrhosisandhepatocellularcarcinomacontributedisproportionatelytoexpenditures,withlifetimecostsforNASHcirrhosisexceeding95,000 per patient [32] These findings underscore that, unlike HBV and HCV where preventive strategies have proven highly cost-effective, NAFLD poses escalating challenges requiring resource-intensive management, with major implications for healthcare budgeting and workforce planning.

While this study offers valuable insights into the global burden of liver disease, this study has several limitations. First, the GBD estimates are model-based, using statistical tools such as CODEm and DisMod-MR. These models rely on assumptions and covariates, which may introduce bias, especially in regions with scarce or poor-quality data. Second, underreporting of cirrhosis is likely in low-SDI countries, where diagnostic capacity, surveillance systems, and access to healthcare remain limited. Third, in some settings, GBD inputs are derived from verbal autopsies, administrative records, or survey data without laboratory or imaging confirmation, potentially affecting diagnostic accuracy and leading to underestimation of the true burden.

In conclusion, this study highlights the evolving nature of liver disease globally, with significant regional and etiological differences. HBV and HCV, alcohol-related liver disease, and NAFLD remain the leading contributors to liver disease burden, with NAFLD becoming a dominant factor in high-SDI regions. Addressing the rising burden of liver disease requires coordinated global efforts, including the expansion of vaccination and antiviral treatment programs for viral hepatitis, as well as interventions to reduce alcohol consumption and tackle the obesity epidemic and metabolic syndrome worldwide.

Conclusion

This study highlights the growing global burden of cirrhosis and chronic liver diseases, primarily driven by HBV, HCV, alcohol use, and NAFLD. HBV, HCV remain major contributors in low- and middle-SDI regions. Although high-SDI regions have made progress in controlling viral hepatitis, NAFLD has become a dominant driver of liver disease in high-income countries and is increasingly prevalent across all SDI levels.